Abstract

Background

The high prevalence rate of asthma represents a major societal burden. Advancements in information technology continue to affect the delivery of patient care in all areas of medicine. Internet-based solutions, social media, and mobile technology could address some of the problems associated with increasing asthma prevalence.

Objective

This review evaluates Internet-based asthma interventions that were published between 2004 and October 2014 with respect to the use of behavioral change theoretical frameworks, applied clinical guidelines, and assessment tools.

Methods

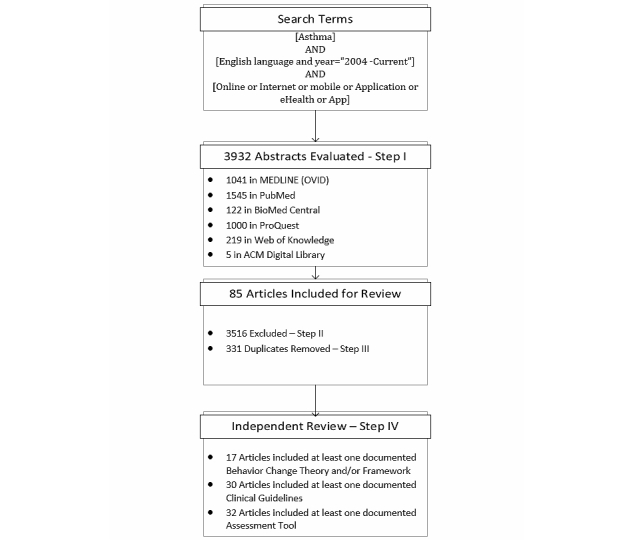

The search term (Asthma AND [Online or Internet or Mobile or Application or eHealth or App]) was applied to six bibliographic databases (Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, BioMed Central, ProQuest Computing, Web of Knowledge, and ACM Digital Library) including only English-language articles published between 2004 and October 2014. In total, 3932 articles matched the priori search terms and were reviewed by the primary reviewer based on their titles, index terms, and abstracts. The matching articles were then screened by the primary reviewer for inclusion or exclusion based on their abstract, study type, and intervention objectives with respect to the full set of priori inclusion and exclusion criteria; 331 duplicates were identified and removed. A total of 85 articles were included for in-depth review and the remaining 3516 articles were excluded. The primary and secondary reviewer independently reviewed the complete content of the 85 included articles to identify the applied behavioral change theories, clinical guidelines, and assessment tools. Findings and any disagreement between reviewers were resolved by in-depth discussion and through a consolidation process for each of the included articles.

Results

The reviewers identified 17 out of 85 interventions (20%) where at least one model, framework, and/or construct of a behavioral change theory were applied. The review identified six clinical guidelines that were applied across 30 of the 85 interventions (35%) as well as a total of 21 assessment tools that were applied across 32 of the 85 interventions (38%).

Conclusions

The findings of this literature review indicate that the majority of published Internet-based interventions do not use any documented behavioral change theory, clinical guidelines, and/or assessment tools to inform their design. Further, it was found that the application of clinical guidelines and assessment tools were more salient across the reviewed interventions. A consequence, as such, is that many Internet-based asthma interventions are designed in an ad hoc manner, without the use of any notable evidence-based theoretical frameworks, clinical guidelines, and/or assessment tools.

Keywords: asthma; self-care; self-management; eHealth, mHealth; mobile health; telehealth; telemedicine; Internet; review

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory disease of the airways with symptoms including cough, breathlessness, and wheezing. According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, there are some 235 million people in the world currently suffering from asthma. The WHO also estimates that asthma is the most common non-communicable disease among children [1,2].

Combined with the aging population trend and increasing cost of health care services, the high prevalence rate of asthma represents a major societal burden as well as a substantial challenge to the traditional models of health care providers, patients, and their families. A number of cost analysis studies have reported that the annual economic cost of asthma due to direct medical costs from hospital stays, as well as indirect costs from lost school and workdays, amounted to more than US $56 billion in the United States in 2007, CAN $1.8 billion in Ontario, Canada in 2011, and €19.3 billion in European adult populations in 2010 [3-5].

Advancements in the field of information technology continue to change patient care in all areas of medicine. Internet-based solutions, social media, and mobile technology could help to mitigate some of the problems associated with the increasing asthma prevalence [6].

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Expert Panel Report 3 (NHLBI EP3) Asthma Guidelines suggest that there is a potential use for information technologies to provide patients with skills to control their asthma and improve outcomes [7,8].

None of the existing literature reviews focused on evaluating Internet-based asthma interventions with respect to the evidence base around the behavioral change theoretical frameworks, applied clinical guidelines, and assessment tools.

The primary objective of this literature review was to identify and evaluate Internet-based asthma interventions that were published between 2004 and October 2014 with respect to the use of the behavioral change, self-care, and self-management theoretical frameworks as well as the application of clinical guidelines and assessment tools.

Methods

Research Questions

We established the following primary research question: What is the use of behavioral change, self-care, and self-management theoretical frameworks within the context of Internet-based asthma interventions?

Our secondary research question was: What is the use of clinical guidelines and assessment tools within the context of Internet-based asthma interventions?

Inclusion Criteria

The review included all asthma-related Internet-based interventions, such as Internet-based applications, electronic diary solutions, mobile apps, and/or any other kind of computer-based applications with the focus on patient-centric Internet-based applications as well as provider-to-patient applications.

The bibliographic databases search included relevant studies and interventions that were published between 2004 and October 2014 and was limited to literature published in the English language.

Exclusion Criteria

The review excluded any electronic record management systems that are provider-centric and used to organize patient visits at the clinic and/or hospital settings such as electronic medical records (EMR), electronic health records (EHR), and hospital information systems (HIS). Also, telemedicine interventions that merely leveraged the conventional wired or wireless telephone technology as a medium to facilitate a verbal communication and/or short message service (SMS) between patients and their providers were excluded. The review excluded any educational-only studies that utilized Web-based resources, such as social media, decision support tools, and wikis, for the sole purpose of providing educational content for asthma patients, caregivers, and/or providers.

The bibliographic databases search excluded studies whose main objective was to design, develop, and assess eHealth tools, such as Web, Internet, and mobile apps, without providing critical analysis of their impact and contribution within a given asthma intervention context.

Search Strategy

Overview

The search term was applied to six bibliographic databases (Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, BioMed Central, ProQuest Computing, Web of Knowledge, and ACM Digital Library) including only English articles published between 2004 and October 2014. The search was conducted in the following steps.

Search Term

We limited the search to English-language articles published between 2004 and October 2014. The search term was:

[Asthma] AND

[English language and year="2004 -Current"] AND

[Online or Internet or Mobile or Application or eHealth or App]

Step I — Abstract Evaluation

The primary reviewer evaluated the abstracts, titles, and index terms of all matching articles in the bibliographic databases where the search term was applied. Based on this preliminary review, all relevant articles were listed for potential inclusion.

Step II — Screening for Inclusion

In this step, the primary reviewer evaluated relevant articles in the preliminary list for final inclusion or exclusion based on their abstract, study type, and intervention focus with respect to the full set of priori inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Step III — Removal of Duplicates

Internal and cross-database duplicates were identified and removed from all included articles from Step II. Duplicates within each database were first identified and removed. Cross-database duplicates were then identified and removed through a manual consolidation process.

Step IV — Independent Review

The complete published papers of all included articles were then reviewed, analyzed, and assessed thoroughly by two reviewers independently. The primary and secondary reviewers independently reviewed the complete content of the included articles to identify the applied theoretical frameworks, clinical guidelines, and assessment tools with the objective to answer the priori research questions. Findings and disagreements between the primary and secondary reviewers were resolved by in-depth discussions and through a consolidation process for each of the included articles.

Results

Overview

In total, and across all six bibliographic databases, 3932 articles matched the priori search terms and were reviewed by the primary reviewer based on their titles, index terms, and abstracts in Step I.

In Step II, 3516 articles were excluded by the primary reviewer on their abstract, study type, and intervention focus that met the priori exclusion criteria.

A total of 331 duplicates were identified and removed in Step III.

In the last step, the remaining 85 articles were included for independent and in-depth review by the two reviewers. Figure 1 depicts the search breakdown and results for all six bibliographic databases.

Figure 1.

Search results from the six bibliographic databases.

The majority of the reviewed studies and interventions reported the following key targeted behaviors [9-13]: (1) managing environmental triggers, (2) accessing asthma services, (3) medication adherence, (4) monitoring peak flow regularly by using portable meters, (5) keeping rescue inhaler accessible, and (6) smoke reduction or cessation.

The findings of the review results will be discussed in three different sections: Theoretical Frameworks, Clinical Guidelines and Assessment Tools, and Other Reviews.

Theoretical Frameworks

Overview

The motive behind conducting this review was to answer the primary research question with respect to whether existing Internet-based interventions for asthma were founded on any behavioral-change theories. And if so, to what extent did these theoretical frameworks inform the design and evaluation of these interventions?

This review identified 17 out of 85 interventions (20%) where at least one model, framework, and/or construct of a behavioral change theory was applied. This implies that the majority of our reviewed interventions did not apply any documented behavioral change theory to inform the design of their interventions. This finding is consistent with what is reported in the literature. Theory-driven strategies for aiding individuals in changing or managing health behaviors are lacking [9].

As such, this review found that there are only a limited number of well-established behavioral change theories and models that were referenced and applied across multiple studies. In total, the reviewers were able to identify 10 behavioral change theories and models that were applied across multiple interventions versus 13 other theories and models that were only applied once within the context of a single study and/or intervention.

Table 1 provides a list of all applied theoretical frameworks and models that were identified across the 85 reviewed interventions.

Table 1.

Applied theoretical frameworks and models of the 85 reviewed Internet-based asthma interventions.

| Theoretical frameworks | Number of studies | Cited interventions |

| Gamification | 4 | [13-16] |

| Health Belief Model | 4 | [10-12,17] |

| Tailoring | 4 | [10-13] |

| Transtheoretical Model | 4 | [9,10,12,17] |

| Attribution Theory | 3 | [11,13,17] |

| Chronic Care Model | 2 | [18,19] |

| Motivational Interviewing | 2 | [11,17] |

| Self-Determination Theory | 2 | [17,20] |

| Social Cognitive Theory | 2 | [13,21] |

| Technology Acceptance Model | 2 | [22,23] |

| Biobehavioral Family Model (BFM) | 1 | [16] |

| Dual Processing Theory | 1 | [13] |

| Ecological Systems Theory | 1 | [24] |

| Instructional Theory | 1 | [13] |

| Intervention Mapping | 1 | [13] |

| Marlatt’s Theory of Relapse | 1 | [17] |

| Motivational Theory | 1 | [13] |

| Norma Engaging Multimedia Design (NEMD) | 1 | [16] |

| Peplau’s Theory of Interpersonal Relations | 1 | [22] |

| Social Learning Theory | 1 | [25] |

| Sociohistoric Theory | 1 | [13] |

| The eHealth Behavior Management Model | 1 | [9] |

| Theory of Planned Behavior | 1 | [9] |

| Watson’s Model of Caring | 1 | [22] |

In the following sections, the theoretical frameworks that were applied in more than three studies will be further analyzed and discussed.

Gamification

In the past, computer and video games were perceived to be a waste of time and harmful in many aspects to those who play such games excessively, especially for the child and adolescent age groups [26,27]. Nevertheless, the advancement in audio-visual and telecommunication technologies has ignited a new era for today’s games. While the term “gamification” is still evolving, it could be defined as “the use of video game elements in non-gaming systems to improve user experience (UX) and user engagement” [28].

There is a growing body of evidence emphasizing the potential benefits of the social, health, and educational science behind computer games [29]. The potential application of computer games in the health domain was well addressed by the Games for Health projects. The project has defined a taxonomy to depict five main types of games used in health care: Preventative, Therapeutic, Assessment, Educational, and Informatics [27].

This review has shown that principles, concepts, and strategies of gamification were only applied in four studies. However, these four studies only targeted children up to 12 years old [13-16]. The reviewers could not cite any Internet-based asthma interventions employing gamification concepts for the adolescent or adults’ population groups.

In one study conducted in 2013, an online peer support group for asthmatic children used an existing commercial networking website, Club Penguin, to help asthmatic children deal with difficult situations in an engaging manner [14].

Another two studies reported the success of an award-winning program called “Okay With Asthma”, where an interactive digital story was developed and delivered online to support children with their asthma and psychosocial management strategies. This was done through leveraging and employing a novel behavioral model, the Biobehavioral Family Model [15,16].

The “Okay With Asthma” program successfully used the five factors (simulation interactivity, construct interactivity, immediacy, feedback, and goals) identified by the Norma Engaging Multimedia Design model to design its usability and feasibility testing approach [16,30].

Simulation interactivity describes the child’s ability to ‘become’ a character in the story, whereas construct interactivity refers to the availability of activities for the child to create or build in the virtual world. Immediacy is the user’s ability to observe all the actions and interactions that take place in the system. Children need feedback to show that their choices matter; without consequences, there would be no point in performing the actions. The model’s final tenet is goal setting. Whether the goal is set extrinsically (by the game developer) or intrinsically (the child determining own goals), it is important for there to be goals to achieve. [31]

As well, the Watch-Discover-Think-Act (WDTA) study [13] provided an applied example of how behavioral and motivation theories could be translated within the context of gamification. The WDTA program developed a game that walks through 18 real-life and four fantasy scenarios. The players, who are children with asthma, have to complete a set of tasks related to asthma self-management in order to progress across scenarios. Feedback is provided as a reinforcement of information for the children and their parents.

As depicted in Table 2, the reviewers were able to validate the translation steps of the behavioral change theoretical methods in the “Watch-Discover-Think-Act” [13] study against a number of other studies, such as the five factors of the Norma Engaging Multimedia Design model that were applied within the context of “Okay With Asthma” [16]. The correlation between the findings of those two different studies validates the impact and influence gamification theories and methods could have to increase patients’ motivation, self-efficacy, and engagement level within the context of Internet-based asthma interventions.

Table 2.

Correlation between the applied theoretical methods and factors of the two studies, “Watch-Discover-Think-Act” and “Okay With Asthma”.

| WDTA (Watch-Discover-Think-Act) | Okay With Asthma |

| Personalized Information | Simulation Interactivity |

| Fantasy Context + Multiple Modalities | Construct Interactivity |

| Learner Control | Immediacy |

| Reinforcement | Feedback |

| Goal Settings | Goals |

Health Belief Model

The Health Belief Model dates back to the 1950s, initially developed by Hochbaum (1958) and Rosenstock (1960), and then extended by Kirscht and Becker in 1974 [32]. The Health Belief Model is a theoretical framework that attempts to study and predict the individual’s health preferences and actions based on observed attitudes and personal beliefs. The model explains the individual’s motivation to take a health care-related action based on the following factors:

(1) The existence of sufficient motivation (or health concern) to make health issues salient of relevant.

(2) The belief that one is susceptible (vulnerable) to a serious health problem or to the sequelae of that illness or condition. This is often termed perceived threat.

(3) The belief that following a particular health recommendation would be beneficial in reducing the perceived threat, and at a subjectively-acceptable cost. [33]

The Health Belief Model was applied in the context of providing individualized messages and communication with patients to promote self-efficacy and better patient engagement [10-12,17].

The Puff City program that was evaluated in six Detroit high schools and reported in four different studies [10-12,17] identified and evaluated three core behaviors: namely, controller medication adherence, rescue inhaler availability, and smoking cessation/reduction. In the event of a negative change in any of the three core behaviors, theory-based health messages and information on asthma control were sent to the patients to sustain their self-efficacy and asthma self-regulation [12].

Tailoring

In the literature, “tailoring” is defined as “…assessment and provision of feedback based on information that is known or hypothesized to be most relevant for each individual participant of a program” [11,34,35], and “…any combination of information or change strategies intended to reach one specific person, based on characteristics that are unique to that person, related to the outcome of interest, and have been derived from an individual assessment” [10,35].

A number of studies and interventions have pointed out the significance of identifying the resistant groups at earlier stages of the intervention. These groups are less motivated to change their behavior and take ownership in managing their asthma. The objective is to use “tailoring” as a means to apply behavioral change theories, such as the Transtheoretical Model and the Health Belief Model, to motivate those subgroups and achieve positive changes in their behaviors with respect to their self-efficacy and asthma management [10-13]. The reviewed studies have utilized “tailoring” to customize the communication and education strategies with the targeted resistant subgroup based on their beliefs, attitude, and personalized information.

Transtheoretical Model

The Transtheoretical Model promotes individuals to change their behaviors for a healthier lifestyle.

The Transtheoretical Model is based on the premise that individuals are in one of five possible stages of change associated with a particular behavior. Precontemplation is the stage in which a person has no interest in changing the behavior. Contemplation is when a person would like to change the behavior someday but is not yet ready. Preparation is when a person is ready to make the change but needs assistance in moving that want into reality. The more active stages include Action and Maintenance. Those in Action have begun the behavior change process. Key to their success is moving the change to Maintenance, where change takes place over time. [9,36]

The review identified three different studies where the concepts of the Transtheoretical Model were applied in the methods’ design and patients’ assessment through the stages of the change [9,10,12,17].

The Asthma Management Demonstration Project was developed to manage the following four asthma-related behaviors for asthma patients among employees and students of Western Michigan University: monitoring peak flow measurements, accessing asthma services, using prescription asthma medications properly, and managing environmental triggers [9]. Based on concepts of Transtheoretical Model, the project developed transactional questioning to stage their asthma patients according to their readiness to change their asthma-related behavior [9].

The Web-based Puff City program has also applied concepts of Transtheoretical Model to motivate their patients to change three core asthma-related behaviors: controller medication adherence, rescue inhaler availability, and smoking cessation/reduction [10,12,17].

Clinical Guidelines and Assessment Tools

Overview

In response to our secondary research question, we found that the application and employment of clinical guidelines and assessment tools were more abundant than theoretical frameworks across the reviewed interventions. The review identified 30 out of 85 interventions (35%) where at least one documented clinical guideline was applied. In total, there were six clinical guidelines applied across the 30 identified interventions as listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Applied clinical guidelines of the 85 reviewed Internet-based asthma interventions.

| Clinical guidelines | Number of studies | Cited interventions |

| National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) | 15 | [10-12,16-18,20-22,37-42] |

| Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Guidelines | 13 | [43-55] |

| British Guideline on the Management of Asthma | 1 | [54] |

| Canadian Asthma Consensus Guidelines (CACG) | 1 | [63] |

| International ERS/ATS Guidelines on Definition, Evaluation and Treatment of Severe Asthma | 1 | [54] |

| Standards for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with COPD | 1 | [47] |

As such, the review identified 32 out of 85 interventions (38%) where at least one documented assessment tool was applied. In total, there were 21 assessment tools applied across the 32 identified interventions as listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Applied assessment tools of the 85 reviewed Internet-based asthma interventions.

| Assessment tools | Number of studies | Cited interventions |

| Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) | 11 | [19,20,44,49,56-62] |

| Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaires (AQLQ) | 9 | [19,44,48,50,59,62,64-66] |

| Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) | 8 | [43,50,52,53,57,61,67,68] |

| Asthma Control Test (ACT) | 8 | [42,51-53,64,67-69] |

| International Survey of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire | 4 | [11,12,55,68] |

| Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ) | 3 | [49,57,60] |

| Child Asthma Control Test (C-ACT) | 3 | [52,53,68] |

| Mini Asthma Quality of Life (Mini AQLQ) | 3 | [56,58,63] |

| Knowledge, Attitude and Self-Efficacy Asthma Questionnaire (KASE-AQ) | 2 | [58,60] |

| Pediatric Asthma Caregivers Quality of Life Questionnaire (PACQLQ) | 2 | [52,53] |

| The Asthma Life Quality Questionnaire (ALQ) | 2 | [56,64] |

| The Consumer Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire and inhalation technique with the standardized checklist of the Dutch Asthma Foundation | 2 | [57,59] |

| Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) | 1 | [63] |

| Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma Questionnaire (ARIA) | 1 | [68] |

| Asthma Behavior Checklist (ABC) | 1 | [25] |

| Asthma Self-Regulatory Development Interview | 1 | [17] |

| Children’s Health Survey for Asthma (CHSA) by the American Academy of Pediatrics | 1 | [70] |

| Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI) | 1 | [25] |

| Illness Management Survey (IMS) | 1 | [67] |

| Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support | 1 | [11] |

| The Royal College of Physicians’ “Three Key Questions” | 1 | [71] |

This review found that many guidelines and assessment tools were broadly adopted by a relatively large number of interventions, for example, the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program referenced across 15 (of the 85) interventions [10-12,16-18,20-22,37-42], the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines referenced across 13 interventions [43-55], and the Asthma Control Questionnaire referenced across 11 interventions [19,20,44,49,56-62].

International Asthma Guidelines

With the aim to employ an evidence base to reduce asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) was launched in 1993 as a collaboration between the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the World Health Organization [72]. The GINA guidelines were referenced in 13 of the 85 reviewed interventions [43-55].

Another example of internationally applied asthma guidelines is the International Survey of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire. Established in 1991, the ISAAC guidelines aimed to investigate asthma in the pediatric population as a measure to control the increasing conditions on the global scale [73]. Items from the ISAAC guidelines were included in the Lung Health Survey in four of the reviewed interventions [11,12,55,68].

National Asthma Guidelines

In response to the increasing asthma challenges in the United States, the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) was initiated in March 1989 by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) [74]. This review has shown that the NAEPP guidelines were the most referenced asthma guidelines across all reviewed interventions as they were implemented in the design of 15 out of the 85 reviewed interventions [10-12,16-18,20-22,37-42].

This review identified a number of national clinical guidelines that were adopted and applied in a smaller number of interventions conducted at the national level, such as the British Guideline on the Management of Asthma [54], the Canadian Asthma Consensus Guidelines (CACG) [63], and the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) in Canada, as well as the standardized checklist of the Dutch Asthma Foundation [57,59].

Pediatric Asthma Guidelines

In addition to the national and international guidelines, the review also identified a number of children-specific guidelines such as the Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ) [43,50,52,53,57,61,67,68], International Survey of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) questionnaire [11,12,55,68], the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI) [25], the Children’s Health Survey for Asthma (CHSA) by the American Academy of Pediatrics [70], and the Child Asthma Control Test (C-ACT) [52,53,68].

Other Reviews

A total of 14 other reviews of Internet- and electronic-based asthma interventions were identified. These reviews did not evaluate Internet-based asthma interventions with respect to the evidence base around the behavioral change theoretical frameworks, applied clinical guidelines, and assessment tools. However, the identified other reviews share similar discussions around main topics such as patients’ perception of Internet-based interventions, limitation of existing studies, and the effect of evolving Internet and mobile technologies on the relationship between asthma patients and their health care providers.

Six of the 14 reviews indicated that Internet-based interventions were well-perceived by asthma patients and their usage was associated with promoting positive health behaviors among asthma patient groups [6,7,75-78]. On the other hand, a number of reviews reported that numerous studies for existing interventions were conducted on a small group of subjects for a limited, and often short, period of time resulting in mixed results with respect to controlling asthma symptoms and improving quality of life for asthma patients [1,7,79-81]. Last, four reviews shared concerns pertaining to the increased diffusion of Internet and mobile technologies into the delivery of care and to its impact on the clinician-patient relationship that could have negative effect on both patients and health care providers [1,7,79,80].

Discussion

Principal Findings

In an attempt to answer the primary research question pertaining to the evidence base around the behavioral change, self-care, and self-management theoretical frameworks applied within the context of the reviewed Internet-based asthma interventions, the reviewers identified 17 out of 85 interventions (20%) where at least one model, framework, and/or construct of a behavioral change theory was applied. This implies that the majority of our reviewed interventions did not apply any documented behavioral change theory to inform their design. As such, this review found that only a limited number of behavioral change theories and models were referenced and applied across multiple studies.

In total, the reviewers were able to identify 10 behavioral change theories and models that were applied across multiple (more than one) interventions versus 13 other theories and models that were only applied within the context of a single study and/or intervention.

Compared to the applied theoretical frameworks, and in response to the secondary research question, the reviewers were able to report that the application and employment of clinical guidelines and assessment tools were more salient across the reviewed interventions. The review identified six clinical guidelines that were applied across 30 of the 85 interventions (35%) as well as a total of 21 assessment tools that were applied across 32 of the 85 interventions (38%).

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines were the most referenced asthma guidelines across all the reviewed interventions as they were implemented in the design of 15 out of the 85 reviewed interventions [10-12,16-18,20-22,37-42].

Limitations

This review has a number of limitations. First, the reviewers searched the literature in six major bibliographic databases between 2004 and October 2014 only; there may be other relative studies published in other databases. Second, the reviewers did not employ any theory or guidelines to evaluate the quality of each included and reviewed study. Thus, all reviewed studies are assumed to be of the same quality.

Conclusions

It was found that the majority of published interventions did not apply behavioral change theory, clinical guidelines, and/or assessment tools to inform their design. Further, it was found that the application of clinical guidelines and assessment tools were more salient across the reviewed interventions. A consequence, therefore, is that many Internet-based asthma interventions are designed in an ad hoc manner, without the use of any notable evidence-based theoretical frameworks, clinical guidelines, and/or assessment tools.

Abbreviations

- ABC

Asthma Behavior Checklist

- ACQ

Asthma Control Questionnaire

- ACT

Asthma Control Test

- ALQ

Asthma Life Quality Questionnaire

- AQHI

Air Quality Health Index

- AQLQ

Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaires

- ATAQ

Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire

- CACG

Canadian Asthma Consensus Guidelines

- C-ACT

Child Asthma Control Test

- CHSA

Children’s Health Survey for Asthma

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ECBI

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory

- eHealth

electronic health

- EHR

electronic health records

- EMR

electronic medical records

- GINA

Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines

- HIS

hospital information system

- IMS

Illness Management Survey

- ISAAC

International Survey of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood questionnaire

- KASE-AQ

Knowledge, Attitude and Self-Efficacy Asthma Questionnaire

- Mini AQLQ

Mini Asthma Quality of Life

- NAEPP

National Asthma Education and Prevention Program

- NHLBI EP3

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Expert Panel Report 3

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- PAQLQ

Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

- SMS

short message service

- UX

user experience

- WDTA

Watch-Discover-Think-Act

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The editor/publisher of this journal (GE) is academic supervisor of the first author, but had no role in making any decisions regarding this paper, which was handled by an associate editor.

References

- 1.McLean Susannah, Chandler David, Nurmatov Ulugbek, Liu Joseph, Pagliari Claudia, Car Josip, Sheikh Aziz. Telehealthcare for asthma: a Cochrane review. CMAJ. 2011 Aug 9;183(11):E733–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101146. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21746825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2013. Nov, [2014-07-20]. Asthma fact sheet N°307 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs307/en/ [PubMed]

- 3.Barnett Sarah Beth L, Nurmagambetov Tursynbek A. Costs of asthma in the United States: 2002-2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Jan;127(1):145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.10.020. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/naepp/, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smetanin P, Stiff D, Briante C, Ahmad S, Wong L, Ler A. Life and economic impact of lung disease in Ontario: 2011 to 2041. RiskAnalytica, on behalf of the Ontario Lung Association. 2011 http://www.riskanalytica.com/?q=node/56. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Accordini Simone, Corsico Angelo G, Braggion Marco, Gerbase Margaret W, Gislason David, Gulsvik Amund, Heinrich Joachim, Janson Christer, Jarvis Deborah, Jõgi Rain, Pin Isabelle, Schoefer Yvonne, Bugiani Massimiliano, Cazzoletti Lucia, Cerveri Isa, Marcon Alessandro, de Marco Roberto. The cost of persistent asthma in Europe: an international population-based study in adults. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;160(1):93–101. doi: 10.1159/000338998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nickels Andrew, Dimov Vesselin. Innovations in technology: social media and mobile technology in the care of adolescents with asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2012 Dec;12(6):607–12. doi: 10.1007/s11882-012-0299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosnaim GS, Powell LH, Rathkopf M. A review of published studies using interactive Internet tools or mobile devices to improve asthma knowledge or health outcomes. Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology. 2012 Jun;25(2):55–63. doi: 10.1089/ped.2011.0112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program . Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bensley Robert J, Mercer Nelda, Brusk John J, Underhile Ric, Rivas Jason, Anderson Judith, Kelleher Deanne, Lupella Melissa, de Jager André C. The eHealth Behavior Management Model: a stage-based approach to behavior change and management. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004 Oct;1(4):A14. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2004/oct/04_0070.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph C L M, Havstad S L, Johnson D, Saltzgaber J, Peterson E L, Resnicow K, Ownby D R, Baptist A P, Johnson C C, Strecher V J. Factors associated with nonresponse to a computer-tailored asthma management program for urban adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2010 Aug;47(6):667–73. doi: 10.3109/02770900903518827. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20642376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph Christine L M, Ownby Dennis R, Havstad Suzanne L, Saltzgaber Jacqueline, Considine Shannon, Johnson Dayna, Peterson Ed, Alexander Gwen, Lu Mei, Gibson-Scipio Wanda, Johnson Christine Cole, Research team members Evaluation of a web-based asthma management intervention program for urban teenagers: reaching the hard to reach. J Adolesc Health. 2013 Apr;52(4):419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.009. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23299008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph Christine L M, Peterson Edward, Havstad Suzanne, Johnson Christine C, Hoerauf Sarah, Stringer Sonja, Gibson-Scipio Wanda, Ownby Dennis R, Elston-Lafata Jennifer, Pallonen Unto, Strecher Victor, Asthma in Adolescents Research Team A web-based, tailored asthma management program for urban African-American high school students. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 May 1;175(9):888–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1244OC. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17290041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shegog Ross, Bartholomew L Kay, Gold Robert S, Pierrel Elaine, Parcel Guy S, Sockrider Marianna M, Czyzewski Danita I, Fernandez Maria E, Berlin Nina J, Abramson Stuart. Asthma management simulation for children: translating theory, methods, and strategies to effect behavior change. Simul Healthc. 2006;1(3):151–9. doi: 10.1097/01.SIH.0000244456.22457.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart Miriam, Letourneau Nicole, Masuda Jeffrey R, Anderson Sharon, McGhan Shawna. Impacts of online peer support for children with asthma and allergies: "It just helps you every time you can't breathe well". J Pediatr Nurs. 2013;28(5):439–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyatt Tami H, Hauenstein Emily J. Pilot testing Okay With Asthma: an online asthma intervention for school-age children. J Sch Nurs. 2008 Jun;24(3):145–50. doi: 10.1622/1059-8405(2008)024[0145:PTOWAA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyatt Tami H, Li Xueping, Huang Yu, Farmer Rachel, Reed Delanna, Burkhart Patricia V. Developing an interactive story for children with asthma. Nurs Clin North Am. 2013 Jun;48(2):271–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu Mei, Ownby Dennis R, Zoratti Edward, Roblin Douglas, Johnson Dayna, Johnson Christine Cole, Joseph Christine L M. Improving efficiency and reducing costs: Design of an adaptive, seamless, and enriched pragmatic efficacy trial of an online asthma management program. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014 May;38(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartmann Christine W, Sciamanna Christopher N, Blanch Danielle C, Mui Sarah, Lawless Heather, Manocchia Michael, Rosen Rochelle K, Pietropaoli Anthony. A website to improve asthma care by suggesting patient questions for physicians: qualitative analysis of user experiences. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(1):e3. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.1.e3. http://www.jmir.org/2007/1/e3/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Gaalen Johanna L, Beerthuizen Thijs, van der Meer Victor, van Reisen Patricia, Redelijkheid Geertje W, Snoeck-Stroband Jiska B, Sont Jacob K. Long-term outcomes of internet-based self-management support in adults with asthma: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(9):e188. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2640. http://www.jmir.org/2013/9/e188/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gustafson David, Wise Meg, Bhattacharya Abhik, Pulvermacher Alice, Shanovich Kathleen, Phillips Brenda, Lehman Erik, Chinchilli Vernon, Hawkins Robert, Kim Jee-Seon. The effects of combining Web-based eHealth with telephone nurse case management for pediatric asthma control: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(4):e101. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1964. http://www.jmir.org/2012/4/e101/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meischke Hendrika, Lozano Paula, Zhou Chuan, Garrison Michelle M, Christakis Dimitri. Engagement in "My Child's Asthma", an interactive web-based pediatric asthma management intervention. Int J Med Inform. 2011 Nov;80(11):765–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.08.002. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21958551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haze Kimberly A, Lynaugh Jillian. Building patient relationships: a smartphone application supporting communication between teenagers with asthma and the RN care coordinator. Comput Inform Nurs. 2013 Jun;31(6):266–71; quiz 272. doi: 10.1097/NXN.0b013e318295e5ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Shu-Ping, Yang Hung-Yu. Exploring key factors in the choice of e-health using an asthma care mobile service model. Telemed J E Health. 2009 Nov;15(9):884–90. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong HE, Arriaga RI. Using an ecological framework to design mobile technologies for pediatric asthma management. The 11th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services; MobileHCI '09; 2009; Bonn, Germany. ACM; 2009. Sep, [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke S-A, Calam R, Morawska A, Sanders M. Developing web-based Triple P 'Positive Parenting Programme' for families of children with asthma. Child Care Health Dev. 2014 Jul;40(4):492–7. doi: 10.1111/cch.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffiths M. Video games and health: Video gaming is safe for most players and can be useful in health care. BMJ. 2005;331(7509):122–123. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7509.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawyer Ben. From cells to cell processors: the integration of health and video games. IEEE Comput Graph Appl. 2008 Dec;28(6):83–5. doi: 10.1109/MCG.2008.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deterding S, Dixon D, Nacke LE, O'Hara K, Sicart M. Gamification: Using game design elements in non-gaming contexts. Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; CHI EA'11; 2011; Vancouver, BC. 2011. http://gamification-research.org/chi2011/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCallum Simon. Gamification and serious games for personalized health. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2012;177:85–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Said NS. An engaging multimedia design model. Proceedings of the 2004 conference on Interaction Design and Children: Building a Community; IDC'04; June 1-3, 2004; Baltimore, MD. New York, NY: ACM; 2004. p. 169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Said N, Rahman S, Yassin SF. Revisiting an engaging experience to identify metacognitive strategies towards developing a multimedia design model. International Journal of Education and Information Technologies. 2009;3(2):115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baum A. Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health, and Medicine. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1997. The Health Belief Model. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenstock I M, Strecher V J, Becker M H. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175–83. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreuter M W, Strecher V J, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: the case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(4):276–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02895958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreuter M W, Skinner C S. Tailoring: what's in a name? Health Educ Res. 2000 Feb;15(1):1–4. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.1. http://her.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10788196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Fava JL, Norman GJ, Redding CA. Smoking cessation and stress management: applications of the Transtheoretical Model of behavior change. Homeostasis in Health and Disease. 1998 Jul;38(5-6):216–233. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farzanfar Ramesh, Finkelstein Joseph, Friedman Robert H. Testing the usability of two automated home-based patient-management systems. J Med Syst. 2004 Apr;28(2):143–53. doi: 10.1023/b:joms.0000023297.50379.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joshi A, Amelung P, Arora M, Finkelstein J. Clinical impact of home automated telemanagement in asthma. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:1000. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/16779287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee Hye-Ran, Yoo Sun K, Jung Seok-Myung, Kwon Na-Young, Hong Chein-Soo. A Web-based mobile asthma management system. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11 Suppl 1:56–9. doi: 10.1258/1357633054461598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malone Francis, Callahan Charles W, Chan Debora S, Sheets Scott, Person Donald A. Caring for children with asthma through teleconsultation: "ECHO-Pac, The Electronic Children's Hospital of the Pacific". Telemed J E Health. 2004;10(2):138–46. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2004.10.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meltzer Eli O, Kelley Norma, Hovell Melbourne F. Randomized, cross-over evaluation of mobile phone vs paper diary in subjects with mild to moderate persistent asthma. Open Respir Med J. 2008;2:72–9. doi: 10.2174/1874306400802010072. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19412327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Sickle D, Magzamen S, Truelove S, Morrison T. Remote monitoring of inhaled bronchodilator use and weekly feedback about asthma management: an open-group, short-term pilot study of the impact on asthma control. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055335. http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deschildre A, Béghin L, Salleron J, Iliescu C, Thumerelle C, Santos C, Hoorelbeke A, Scalbert M, Pouessel G, Gnansounou M, Edmé J-L, Matran R. Home telemonitoring (forced expiratory volume in 1 s) in children with severe asthma does not reduce exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2012 Feb;39(2):290–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00185310. http://erj.ersjournals.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21852334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hashimoto Simone, Brinke Anneke Ten, Roldaan Albert C, van Veen Ilonka H, Möller Gertrude M, Sont Jacob K, Weersink Els J M, van der Zee Jaring S, Braunstahl Gert-Jan, Zwinderman Aeilko H, Sterk Peter J, Bel Elisabeth H. Internet-based tapering of oral corticosteroids in severe asthma: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2011 Jun;66(6):514–20. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.153411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hung Shu-Hui, Tseng Huan Chin, Tsai Wen Ho, Lin Hsin Hung, Cheng Jen Hsien, Chang Yi-Ming. Care for Asthma via Mobile Phone (CAMP) Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;126:137–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jan Ren-Long, Wang Jiu-Yao, Huang Mei-Chih, Tseng Shin-Mu, Su Huey-Jen, Liu Li-Fan. An internet-based interactive telemonitoring system for improving childhood asthma outcomes in Taiwan. Telemed J E Health. 2007 Jun;13(3):257–68. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu W-T, Huang C-D, Wang C-H, Lee K-Y, Lin S-M, Kuo H-P. A mobile telephone-based interactive self-care system improves asthma control. Eur Respir J. 2011 Feb;37(2):310–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00000810. http://erj.ersjournals.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20562122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rasmussen Linda M, Phanareth Klaus, Nolte Hendrik, Backer Vibeke. Internet-based monitoring of asthma: a long-term, randomized clinical study of 300 asthmatic subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005 Jun;115(6):1137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Meer Victor, van Stel Henk F, Bakker Moira J, Roldaan Albert C, Assendelft Willem J J, Sterk Peter J, Rabe Klaus F, Sont Jacob K, SMASHING (Self-Management of Asthma Supported by Hospitals‚ ICT‚ Nurses and General practitioners) Study Group Weekly self-monitoring and treatment adjustment benefit patients with partly controlled and uncontrolled asthma: an analysis of the SMASHING study. Respir Res. 2010;11:74. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-74. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1465-9921/11/74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willems Daniëlle CM, Joore Manuela A, Hendriks Johannes J E, Nieman Fred H M, Severens Johan L, Wouters Emiel F M. The effectiveness of nurse-led telemonitoring of asthma: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008 Aug;14(4):600–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uysal Mehmet Atilla, Mungan Dilsad, Yorgancioglu Arzu, Yildiz Fusun, Akgun Metin, Gemicioglu Bilun, Turktas Haluk, Study Group‚ Turkish Asthma Control Test (TACT)‚ Turkey Asthma control test via text messaging: could it be a tool for evaluating asthma control? J Asthma. 2013 Dec;50(10):1083–9. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.832294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voorend-van Bergen Sandra, Vaessen-Verberne Anja A, Landstra Anneke M, Brackel Hein J, van den Berg Norbert J, Caudri Daan, de Jongste Johan C, Merkus Peter J, Pijnenburg Mariëlle W. Monitoring childhood asthma: web-based diaries and the asthma control test. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Jun;133(6):1599–605.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hofstede J, de Bie J, van Wijngaarden B, Heijmans M. Knowledge, use and attitude toward eHealth among patients with chronic lung diseases. Int J Med Inform. 2014 Dec;83(12):967–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ram Felix S, McNaughton Wendy. Giving Asthma Support to Patients (GASP): a novel online asthma education, monitoring, assessment and management tool. J Prim Health Care. 2014;6(3):238–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wanick Sarinho S, Menezes Júnior Jv, Gusmão C, Lyra NRS. Experience in the development of a mobile diagnosis support system for asthma: Intelimed. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014 Feb;133(2):AB127–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Araújo L, Jacinto T, Moreira A, Castel-Branco M G, Delgado L, Costa-Pereira A, Fonseca J. Clinical efficacy of web-based versus standard asthma self-management. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22(1):28–34. http://www.jiaci.org/issues/vol22issue1/vol22issue01-4.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rikkers-Mutsaerts E R V M, Winters A E, Bakker M J, van Stel H F, van der Meer V, de Jongste J C, Sont J K. Internet-based self-management compared with usual care in adolescents with asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012 Dec;47(12):1170–9. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryan Dermot, Price David, Musgrave Stan D, Malhotra Shweta, Lee Amanda J, Ayansina Dolapo, Sheikh Aziz, Tarassenko Lionel, Pagliari Claudia, Pinnock Hilary. Clinical and cost effectiveness of mobile phone supported self monitoring of asthma: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e1756. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1756. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=22446569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Meer Victor, Bakker Moira J, van den Hout Wilbert B, Rabe Klaus F, Sterk Peter J, Kievit Job, Assendelft Willem J J, Sont Jacob K, SMASHING (Self-Management in Asthma Supported by Hospitals‚ ICT‚ Nurses and General Practitioners) Study Group Internet-based self-management plus education compared with usual care in asthma: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jul 21;151(2):110–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-2-200907210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Meer Victor, van Stel Henk F, Detmar Symone B, Otten Wilma, Sterk Peter J, Sont Jacob K. Internet-based self-management offers an opportunity to achieve better asthma control in adolescents. Chest. 2007 Jul;132(1):112–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vasbinder Erwin C, Janssens Hettie M, Rutten-van Mölken Maureen P M H, van Dijk Liset, de Winter Brenda C M, de Groot Ruben C A, Vulto Arnold G, van den Bemt Patricia M L A, e-MATIC Study Group e-Monitoring of Asthma Therapy to Improve Compliance in children using a real-time medication monitoring system (RTMM): the e-MATIC study protocol. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-38. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6947/13/38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morrison Deborah, Wyke Sally, Thomson Neil C, McConnachie Alex, Agur Karolina, Saunderson Kathryn, Chaudhuri Rekha, Mair Frances S. A Randomized trial of an Asthma Internet Self-management Intervention (RAISIN): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:185. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-185. http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/15//185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Licskai Christopher, Sands Todd W, Ferrone Madonna. Development and pilot testing of a mobile health solution for asthma self-management: asthma action plan smartphone application pilot study. Can Respir J. 2013 Aug;20(4):301–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/906710. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23936890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cruz-Correia Ricardo, Fonseca João, Lima Luís, Araújo Luís, Delgado Luís, Castel-Branco Maria Graça, Costa-Pereira Altamiro. Web-based or paper-based self-management tools for asthma--patients' opinions and quality of data in a randomized crossover study. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;127:178–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mayers I, Ohinmaa A, Vethanayagam D, Sharpe HM, O’Hara C, Majaesic C, Jacobs P. TThe virtual asthma clinic: Managing asthma patients online. Chest. 2005 Oct 01;128(4_MeetingAbstracts):244S–244S. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4_MeetingAbstracts.244S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin Hsueh-Chun, Chiang Li-Chi, Wen Tzu-Ning, Yeh Kuo-Wei, Huang Jing-Long. Development of online diary and self-management system on e-Healthcare for asthmatic children in Taiwan. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2014 Oct;116(3):299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mulvaney Shelagh A, Ho Yun-Xian, Cala Cather M, Chen Qingxia, Nian Hui, Patterson Barron L, Johnson Kevin B. Assessing adolescent asthma symptoms and adherence using mobile phones. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(7):e141. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2413. http://www.jmir.org/2013/7/e141/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zomer-Kooijker Kim, van Erp Francine C, Balemans Walter A F, van Ewijk Bart E, van der Ent Cornelis K, Expert Network for Children with Respiratory and Allergic Symptoms The expert network and electronic portal for children with respiratory and allergic symptoms: rationale and design. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-9. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/13/9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burbank AJ, Hall-Barrow J, Denman RR, Lewis SD, Hewes M, Schellhase DE, Rettiganti M, Luo C, Bylander LA, Brown RH, Perry TT. There's an app for that: A pilot and feasibility study of mobile-based asthma action plans. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2013 Feb;131(2):AB161–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arnold Renée Jg, Stingone Jeanette A, Claudio Luz. Computer-assisted school-based asthma management: a pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2012;1(2):e15. doi: 10.2196/resprot.1958. http://www.researchprotocols.org/2012/2/e15/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cleland Jennifer, Caldow Jan, Ryan Dermot. A qualitative study of the attitudes of patients and staff to the use of mobile phone technology for recording and gathering asthma data. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(2):85–9. doi: 10.1258/135763307780096230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) [2014-07-20]. http://www.ginasthma.org/About-Us.

- 73.The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. [2014-07-20]. http://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/

- 74.The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) 2013. [2014-07-20]. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/naepp/

- 75.Hieftje Kimberly, Edelman E Jennifer, Camenga Deepa R, Fiellin Lynn E. Electronic media-based health interventions promoting behavior change in youth: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2013 Jun;167(6):574–80. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1095. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/23568703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jaana Mirou, Paré Guy, Sicotte Claude. Home telemonitoring for respiratory conditions: a systematic review. Am J Manag Care. 2009 May;15(5):313–20. http://www.ajmc.com/pubMed.php?pii=11123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Gaalen Johanna L, Hashimoto Simone, Sont Jacob K. Telemanagement in asthma: an innovative and effective approach. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Jun;12(3):235–40. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283533700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tran Nancy, Coffman Janet M, Sumino Kaharu, Cabana Michael D. Patient reminder systems and asthma medication adherence: a systematic review. J Asthma. 2014 Jun;51(5):536–43. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.888572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.García-Lizana Francisca, Sarría-Santamera Antonio. New technologies for chronic disease management and control: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(2):62–8. doi: 10.1258/135763307780096140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McLean Susannah, Chandler David, Nurmatov Ulugbek, Liu Joseph, Pagliari Claudia, Car Josip, Sheikh Aziz. Telehealthcare for asthma: a Cochrane review. CMAJ. 2011 Aug 9;183(11):E733–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101146. http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21746825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marcano Belisario José S, Huckvale Kit, Greenfield Geva, Car Josip, Gunn Laura H. Smartphone and tablet self management apps for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD010013. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010013.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]