Abstract

It is clinically useful to distinguish between two types of hereditary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI): a ‘pure’ type characterized by loss of water only and a complex type characterized by loss of water and ions. Patients with congenital NDI bearing mutations in the vasopressin 2 receptor gene, AVPR2, or in the aquaporin-2 gene, AQP2, have a pure NDI phenotype with loss of water but normal conservation of sodium, potassium, chloride and calcium. Patients with hereditary hypokalemic salt-losing tubulopathies have a complex phenotype with loss of water and ions. They have polyhydramnios, hypercalciuria and hypo- or isosthenuria and were found to bear KCNJ1 (ROMK) and SLC12A1 (NKCC2) mutations. Patients with polyhydramnios, profound polyuria, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, metabolic alkalosis and sensorineural deafness were found to bear BSND mutations. These clinical phenotypes demonstrate the critical importance of the proteins ROMK, NKCC2 and Barttin to transfer NaCl in the medullary interstitium and thereby to generate, together with urea, a hypertonic milieu. This editorial describes two new developments: (i) the genomic information provided by the sequencing of the AQP2 gene is key to the routine care of these patients, and, as in other genetic diseases, reduces health costs and provides psychological benefits to patients and families and (ii) the expression of AQP2 mutants in Xenopus oocytes and in polarized renal tubular cells recapitulates the clinical phenotypes and reveals a continuum from severe loss of function with urinary osmolalities <150 mOsm/kg H2O to milder defects with urine osmolalities >200 mOsm/kg H2O.

Keywords: aquaporin-2 mutations, autosomal-dominant and -recessive nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, genetic testing, hereditary polyuric states

Identification of loss-of-function AQP2 mutations responsible for autosomal-recessive or autosomal-dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

Complex polyuric cases as described in the abstract are included in [1–6] and the benefit of genomic information in [7].

On the basis of 1-desamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin (dDAVP) infusion studies and measurements of plasma cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels following pharmacological intravenous doses of dDAVP, a vasopressin V2 synthetic analog, we first suggested that X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) was a pre-cyclic AMP defect [8, 9]. Male patients with X-linked NDI did not stimulate their coagulation factor release or plasma cyclic AMP level after a pharmacological infusion of dDAVP, a suggestion of a loss of function of both renal and extrarenal vasopressin V2 receptors. As in many other X-linked diseases, males are severely affected with polyuria and polydipsia, by contrast, women are rarely symptomatic (for a discussion on symptomatic heterozygous female patients bearing AVPR2 mutations see: [10]). Subsequent haplotype analysis of X-linked NDI in ancestrally independent families followed by my laboratory revealed that all affected male subjects were segregated with X-q28 markers where the vasopressin receptor gene is localized [11]. At the same time, Birnbaumer [12] and her team cloned the vasopressin V2 receptor by expression, the readout signal was again stimulation of cAMP from transfected cells, and, in collaboration with her, we rapidly demonstrated that a frameshift mutation in the AVPR2 gene, the gene coding for the vasopressin V2 receptor, was responsible for X-linked NDI [13].

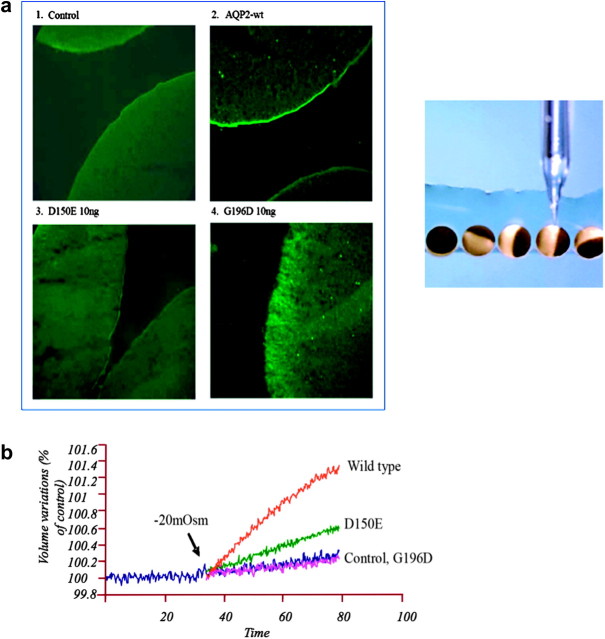

Using dDAVP infusion studies and other families with severe polyuric characteristics in both male and female individuals, a non-X-linked form of NDI with a post-receptor (post-cAMP) defect was suggested [14–16]. A patient who presented shortly after birth with typical features of NDI but who exhibited normal coagulation and normal fibrinolytic and vasodilatory responses to dDAVP was shown to be a compound heterozygote for two missense mutations (R187C and S217P) in the AQP2 gene [17]. Expression of each of these two mutations in Xenopus oocytes revealed non-functional water channels. The oocytes of the African clawed frog Xenopus have provided a most useful test bed for looking at the functioning of many channel proteins. (See recent characterization of proteins with gain of function responsible for autosomal-dominant pseudohypoaldosteronism type II [18].) Oocytes are large cells about to become mature eggs ready for fertilization. They have all the normal translation machinery of living cells, so they will respond to the injection of messenger RNA by making the encoded protein [19]. This convenient expression system was key to the discovery of AQP1 by Agre [20] because frog oocytes have very low permeability and survive even in freshwater ponds. A representation of the injection process and expression of two AQP2 naturally occurring mutants responsible for autosomal-recessive NDI are described in Figure 1a. When subjected to a 20-mOsm osmotic shock, control oocytes have exceedingly low water permeability but test oocytes become highly permeable to water. These osmotic water permeability assays demonstrated an absence or very low water transport of the complementary RNA with AQP2 mutations (Figure 1b). Immunofluorescence and immunoblot studies demonstrated that these recessive mutants were retained in the endoplasmic reticulum [21, 22].

Fig. 1.

(a) Immunofluorescence of AQP2 expressed in oocytes. Oocytes were not injected (1 control) or injected with either AQP2-wt (2, 1 ng), AQP2-D150E (3, 10 ng) or AQP2-G196D (4, 10 ng) messenger RNAs and incubated for 3 days prior to assay. Oocytes were immunostained and visualized with antibodies to AQP2. The injection process is represented in the right of the figure [21]. (b) Determination of water permeabilities (Pf) of wild-type (WT) AQP2 and mutants expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Oocytes were injected with either AQP2-wt (1 ng), AQP2-D150E (10 ng) or AQP2-G196D (10 ng) messenger RNAs and incubated for 2 days prior to assay. Determination of water permeabilities was performed by evaluation of volume increase in oocytes as induced by a 20-mosmol/kg H2O hypotonic shock [21].

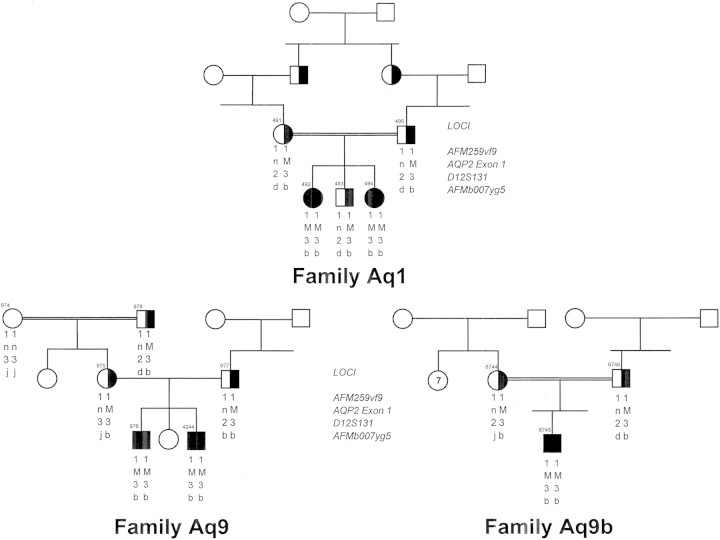

Of interest, in the first identification of AQP2 mutants by the Nijmegen group [17], the sequencing of the AQP2 gene in this isolated patient with autosomal-recessive diabetes insipidus followed a candidate gene approach guided by new understanding of the necessity, after vasopressin recognition and signaling, to insert water channels in the luminal membrane of principal cells of the collecting ducts to achieve water reabsorption [23]. We used the new sequencing data provided by Deen et al. to solve the molecular identification of NDI in two inbred Pakistani girls with non-X-linked NDI originally reported by Langley et al. [16]. They were found to be homozygous for the AQP2 V71M mutation, a recurrent mutation in Pakistani kindred since two other children from two other Pakistani families living in the UK, said to be unrelated, were found to bear the same mutation on the same AQP2 haplotype (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Pedigree of three Pakistani families referred to our laboratory each bearing the V71M AQP2 mutation (M). Family Aqp1 was first described by Langley [16]. Squares and circles represent male and female subjects, respectively, with unaffected individuals (open symbols), carriers (half-filled symbols) and affected individuals (solid symbol); n indicates normal allele. Haplotypes consist of markers that flank the AQP2 gene and that have been described previously [24]. The alleles bearing the individual mutations are identical suggesting a common ancestry.

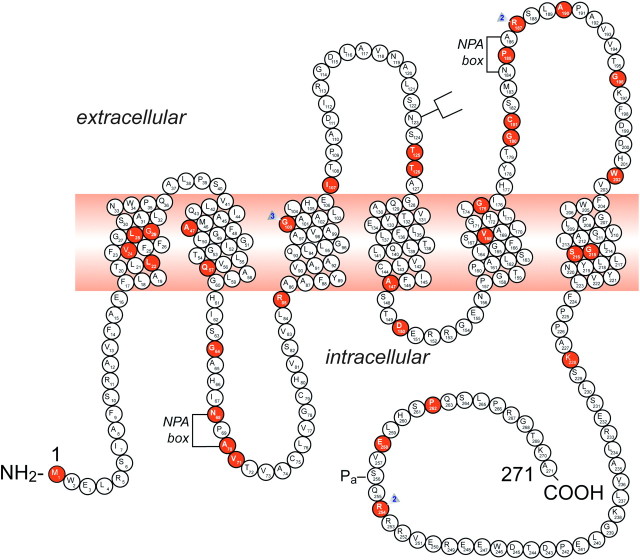

To date, 46 putative disease-causing AQP2 mutations have been identified in 52 NDI families (Table 1 and Figure 3). AQP2 mutations in autosomal-recessive NDI, which are located throughout the gene, result in misfolded proteins that are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (Table 1; Figure 3). In contrast, the dominant mutations reported to date are located in the region that codes for the carboxyl terminus of AQP2 [55]. Dominant AQP2 mutants form heterotetramers with wt-AQP2 and are misrouted [28, 36, 40, 45–48, 51–54]. Patients bearing these dominant mutations have a less severe phenotype as compared to patients who are compound heterozygotes or homozygotes for recessive mutations: the patient and her daughter first described to bear the AQP2-E258K-dominant mutation increased their urine osmolality to 350 mOsm/kg H2O following dDAVP [45]. Also the patient with a detailed phenotype described by Robertson and Koop [25] increased her urine osmolality to 220 mOsm/kg H2O during a mildly hypertonic dehydration, to 258 mOsm/kg H2O after dDAVP and to 305 mOsm/kg H2O after hydrochlorothiazide and indomethacin. This patient was found to be heterozygous for the R254Q mutation, possibly interfering with the S256 phosphorylation site [40]. In the mutant AQP2 (763–772) knockin mice, Sohara et al. [56] demonstrated a slight increase in urine osmolality following dehydration but a marked increase after the administration of Rolipram, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor.

Table 1.

Listing of 46 putative disease-causing AQP2 mutations

| Count | No. of families | Name of mutation | Domain | Nucleotide change | Predicted consequence | Reference |

| Missense [25] | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | M1I | NH2 | ATG-to-ATT | Met-to-Ile | Sahakitrungruang et al. [26] |

| 2 | 1 | L22V | TMI | CTC-to-GTC | Leu-to-Val | Canfield et al. [27] |

| 3 | 1 | V24A | TMI | Val-to-Ala | Leduc-Nadeau et al. [22] | |

| 4 | 1 | L28P | TMI | CTC-to-CCC | Leu-to-Pro | Marr et al. [28] |

| 5 | 1 | G29S | TM1 | Gly-to-Ser | Sahakitrungruang et al. [26] | |

| 6 | 2 | A47V | TMII | GCG-to-GTG | Ala-to-Val | Marr et al. [28]; Muller et al. [29] |

| 7 | 2 | Q57P | TMII | CAG-to-CCG | Glu-to-Pro | Lin et al. [24] |

| 8 | 1 | G64R | CII | GGG-to-AGG | Gly-to-Arg | van Lieburg et al. [30] |

| 9 | 1 | N68S | CII | AAC-to-AGC | Asn-to-Ser | Mulders et al. [31] |

| 10 | 1 | A70D | CII | GCC-to-GAC | Ala-to-Asp | Cheong et al. [32] |

| 11 | 2 | V71M | CII | GTG-to-ATG | Val-to-Met | Marr et al. [28] |

| 12 | 2 | G100V | TMIII | GGA-to-GTA | Gly-to-Val | Lin et al. [24] |

| 13 | 1 | G100R | TMIII | GGA-to-AGA | Gly-to-Arg | Carroll et al. [33] |

| 14 | 1 | I107D | EII | ATC-to-AAC | Ile-to-Asp | Zaki et al. [34] |

| 15 | 1 | T125M | EII | ACG-to-ATG | Thr-to-Met | Goji et al. [35]; Kuwahara [36] (same family) |

| 16 | 1 | T126M | EII | ACG-to-ATG | Thr-to-Met | Mulders et al. [31] |

| 17 | 1 | A147T | TMIV | GCC-to-ACC | Ala-to-Thr | Mulders et al. [31] |

| 18 | 2 | D150E | ICII | GAT-to-GAA | Asp-to-Glu | Guyon et al. [21]; Iolascon et al. [37] |

| 19 | 1 | V168M | TMV | GTG-to-ATG | Val-to-Met | Vargas-Poussou et al. [38] |

| 20 | 1 | G175R | TMV | GGG-to-AGG | Gly-to-Arg | Goji et al. [35]; Kuwahara [36] (same family); Boccalandro et al. [39] |

| 21 | 1 | G180S | EIII | GGC-to-AGC | Gly-to-Ser | Carroll et al. [33] |

| 22 | 1 | C181W | EIII | TGC-to-TGG | Cys-to-Trp | Canfield et al. [27] |

| 23 | 1 | P185A | EIII | CCT-to-GCT | Pro-to-Ala | Marr et al. [28] |

| 24 | 3 | R187C | EIII | CGC-to-TGC | Arg-to-Cys | Deen et al. [17]; van Lieburg et al. [30]; de Mattia et al. [40]; Leduc-Nadeau et al. [22] |

| 25 | 1 | R187H | EIII | CGC-to-CAC | Arg-to-His | Cheong 2005 #1846 [32] |

| 26 | 1 | A190T | EIII | GCT-to-ACT | Ala-to-Thr | Kuwahara [36]; de Mattia et al. [40] |

| 27 | 1 | G196D | EIII | GGC-to-GAC | Gly-to-Asp | Guyon et al. [21] |

| 28 | 1 | W202C | EIII | TGG-to-TGT | Trp-to-Cys | Oksche et al. [41] |

| 29 | 1 | G215C | TMVI | GGC-to-TGC | Gly-to-Cys | Iolascon et al. [37] |

| 30 | 2 | S216P | TMVI | TCC-to-CCC | Ser-to-Pro | Deen et al. [17]; Vargas-Poussou et al. [38] |

| 31 | 1 | S216F | TMVI | TCC-to-TTC | Ser-to-Phe | Moon et al. [42] |

| 32 | 1 | K228E | CIV | Lys-to-Glu | Leduc-Nadeau et al. [22] | |

| 33 | 1 | R254Q | CIV | CGG-to-CAG | Arg-to-Gln | Robertson et al. [25]; Savelkoul et al. [43] |

| 34 | 1 | R254L | CIV | CGG-to-CTG | Arg-to-Leu | de Mattia et al. [40]; de Mattia et al. [44] |

| 35 | 1 | E258K | CIV | GAG-to-AAG | Glu-to-Lys | Mulders et al. [45]; Kamsteeg et al. [46]; Kamsteeg et al. [47]; Kamsteeg et al. [48] |

| 36 | 2 | P262L | CIV | CCG-to-CTG | Pro-to-Leu | Kuwahara [36]; de Mattia et al. [40] |

| Nonsense [2] | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | R85X | CII | CGA-to-TGA | Arg-to-stop | Vargas-Poussou et al. [38]; Bircan et al. [49] |

| 2 | 1 | G100X | TMIII | GGA-to-TGA | Gly-to-stop | Hochberg et al. [50] |

| Frameshift [6] | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 369delC | EII | 1bp deletion | Stop at Codon 131 | van Lieburg et al. [30] |

| 2 | 1 | 721delG | CIV | 1 bp deletion | Post-elongation | Kuwahara et al. [51]; Ohzeki et al. [52] |

| 3 | 1 | 727delG | CIV | 1 bp deletion | Post-elongation | Marr et al. [53] |

| 4 | 1 | 763-772del | CIV | 10 bp deletion | Post-elongation | Kuwahara et al. [51] |

| 5 | 1 | 779–780insA | CIV | 1 bp insertion | Post-elongation | Kamsteeg et al. [54] |

| 6. | 1 | 812-818del | CIV | 7 bp deletion | Post-elongation | Kuwahara et al. [51] |

| Splice-site [2] | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | IVS2-1G>A | NA | G-to-A | NA | D. G. Bichet et al., unpublished |

| 2 | 1 | IVS3+1G>A | NA | G-to-A | NA | Marr et al. [53] |

| 46 | 53 | Note: a family was counted only once if the affected child was homozygous or if the affected child was compound heterozygous | ||||

Fig. 3.

A representation of the AQP2 protein and identification of 46 putative disease-causing AQP2 mutations. A monomer is represented with six transmembrane helices. The location of the PKA phosphorylation site (Pa) is indicated. The extracellular, transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains are defined according to Deen et al. [17]. Solid symbols indicate the location of the mutations (for references, view Table 1): M1I; L22V; V24A; L28P; G29S; A47V; Q57P; G64R; N68S; A70D; V71M; R85X; G100X; G100V; G100R; I107D; 369delC; T125M; T126M; A147T; D150E; V168M; G175R; G180S; C181W; P185A; R187C; R187H; A190T; G196D; W202C; G215C; S216P; S216F; K228E; R254Q; R254L; E258K and P262L. GenBank accession numbers—AQP2: AF147092, Exon 1; AF147093, Exons 2 through 4. NPA motifs and the N-glycosylation site are also indicated.

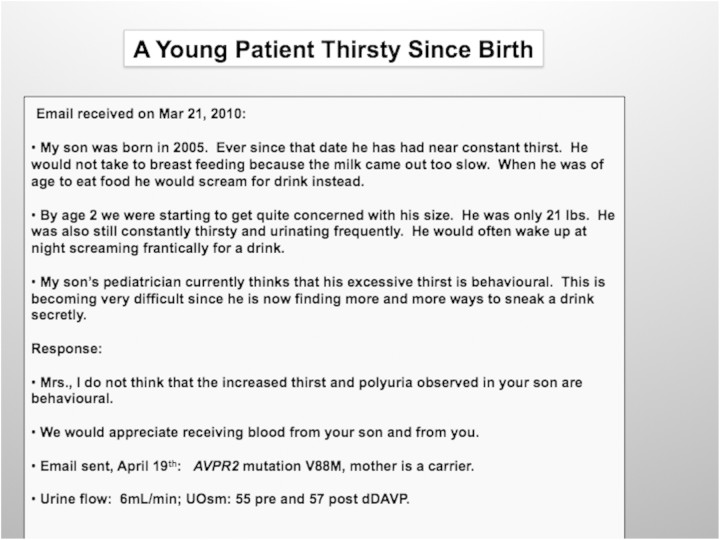

In patients with hereditary polyuria, an X-linked inheritance will suggest X-linked AVPR2 mutations and autosomal-recessive cases will be in favor of AQP2 mutations but we are recommending the sequencing analysis of AVPR2 first and then AQP2 genes in all patients. These genes are, with a few exceptions, relatively small and easy to sequence. This genomic information is key to the routine care of patients with congenital polyuria and, as in other genetic diseases, reduces health costs and provides psychological benefits to patients and their families: an example of the possibility to help families living at a distance from a referral center is given in Figure 4.

Fig. 4.

A young patient's thirsty since birth.

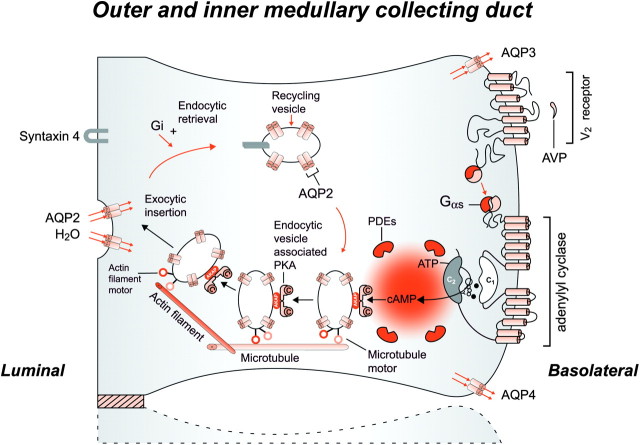

Signaling of vasopressin and insertion of AQP2 water channels in the luminal membrane of principal cells of the collecting duct: the work of five Nobel Prize recipients

The transfer of water across the principal cells of the collecting ducts is now known at such a detailed level that billions of molecules of water traversing the membrane can be represented; see useful teaching tools at http://www.mpibpc.gwdg.de/abteilungen/073/gallery.html and http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/research/aquaporins. The 2003 Nobel Prize in chemistry was awarded to Peter Agre and Roderick MacKinnon, who solved two complementary problems presented by the cell membrane: how does a cell let one type of ion through the lipid membrane to the exclusion of other ions? And how does it permeate water without ions? This contributed to creating momentum and renewed interest in basic discoveries related to the transport of water and indirectly to diabetes insipidus [57, 58]. The first step in the action of AVP (Synthetized by du Vigneaud, Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1955) [59] on water excretion is its binding to arginine vasopressin type 2 receptors (hereafter referred to as V2 receptors) on the basolateral membrane of the collecting duct cells (Figure 5). The human AVPR2 gene that codes for the V2 receptor is located in the chromosome region Xq28 and has three exons and two small introns [12, 60]. The sequence of the complementary DNA predicts a polypeptide of 371 amino acids with seven transmembrane, four extracellular and four cytoplasmic domains. The activation of the V2 receptor on renal collecting tubules stimulates adenylyl cyclase via the stimulatory G protein (Gs) (1994 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine to Rodbell and Gilman for signal transduction and G-proteins) and promotes the cAMP-mediated incorporation of water channels into the luminal surface of these cells [61]. E. Sutherland and T. Rall isolated cAMP in 1956 and Sutherland was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1971 [62]. There are two ubiquitously expressed intracellular cAMP receptors: (i) the classical protein kinase A (PKA) that is a cAMP-dependent protein kinase and (ii) the recently discovered exchange protein directly activated by cAMP that is a cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Both these receptors contain an evolutionally conserved cAMP-binding domain that acts as a molecular switch for sensing intracellular cAMP levels to control diverse biological functions [63]. Several proteins participating in the control of cAMP-dependent AQP2 trafficking have been identified; for example, A-kinase-anchoring proteins tethering PKA to cellular compartments; phosphodiesterases regulating the local cAMP level; cytoskeletal components such as F-actin and microtubules; small GTPases of the Rho family controlling cytoskeletal dynamics; motor proteins transporting AQP2-bearing vesicles to and from the plasma membrane for exocytic insertion and endocytic retrieval and SNAREs inducing membrane fusions, hsc70, a chaperone important for endocytic retrieval. These processes are the molecular basis of the vasopressin-induced increase in the osmotic water permeability of the apical membrane of the collecting tubule [64–66].

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of the effect of vasopressin (AVP) to increase water permeability in the principal cells of the collecting duct. AVP is bound to the V2 receptor (a G-protein-linked receptor) on the basolateral membrane. The basic process of G-protein-coupled receptor signaling consists of three steps: a hepta-helical receptor that detects a ligand (in this case, AVP) in the extracellular milieu, a G-protein (Gα s) that dissociates into a subunits bound to guanosine triphosphate and bg subunits after interaction with the ligand-bound receptor and an effector (in this case, adenylyl cyclase) that interacts with dissociated G-protein subunits to generate small molecule second messengers. AVP activates adenylyl cyclase, increasing the intracellular concentration of cAMP. The topology of adenylyl cyclase is characterized by two tandem repeats of six hydrophobic transmembrane domains separated by a large cytoplasmic loop and terminates in a large intracellular tail. The dimeric structure (C1 and C2) of the catalytic domains is represented. Conversion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to cAMP takes place at the dimer interface. Two aspartate residues (in C1) coordinate two metal co-factors (Mg2+ or Mn2+ represented here as two small black circles), which enable the catalytic function of the enzyme. Adenosine is shown as an open circle and the three phosphate groups (ATP) are shown as smaller open circles. PKA is the target of the generated cAMP. The binding of cAMP to the regulatory subunits of PKA induces a conformational change, causing these subunits to dissociate from the catalytic subunits. These activated subunits (C) as shown here are anchored to an aquaporin-2 (AQP2)-containing endocytic vesicle via an A-kinase-anchoring protein. The local concentration and distribution of the cAMP gradient are limited by phosphodiesterases (PDEs). Cytoplasmic vesicles carrying the water channels (represented as homotetrameric complexes) are fused to the luminal membrane in response to AVP, thereby increasing the water permeability of this membrane. The dissociation of the A-kinase-anchoring protein from the endocytic vesicle is not represented. Microtubules and actin filaments are necessary for vesicle movement toward the membrane. When AVP is not available, AQP2 water channels are retrieved by an endocytic process, and water permeability returns to its original low rate. Aquaporin-3 (AQP3) and aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channels are expressed constitutively at the basolateral membrane.

How could we decrease urine flow in patients bearing AQP2 mutations?

The actions of vasopressin in the distal nephron are possibly modulated by prostaglandin E2, nitric oxide [67] and by luminal calcium concentration. PGE2 is synthesized and released in the collecting duct, which expresses all four E-prostanoid receptors (EP1–4). Both EP2 and EP4 can signal via increased cAMP. Olesen et al. [68] hypothesized that selective EP receptor stimulation could mimic the effects of vasopressin and demonstrated that, at physiological levels, PGE2 markedly increased apical membrane abundance and phosphorylation of AQP2 in vitro and ex vivo, leading to increased cell water permeability. In their experiments, both EP2- and EP4-selective agonists were able to mimic these effects. Furthermore, an EP2 agonist was able to positively regulate urinary-concentrating mechanisms in an animal model of NDI where AVPR2 receptors were blocked by Tolvaptan, a non-peptide V2 antagonist. These results reveal an alternative mechanism for regulating water transport in the collecting duct that have major importance for understanding whole-body water homeostasis and provide a rationale for investigations into EP receptor agonist use in X-linked NDI treatment.

In patients with AQP2 mutations, bypassing the vasopressin V2 receptor will not be of any therapeutic value; therefore, the classical decrease in osmotic load described by Orloff and Earley [69], well before any molecular identification of the genes responsible for hereditary NDI, should be used. When the urine osmolality is fixed, as in nephrogenic DI, the urine output is determined by solute excretion. Suppose that the maximum urine osmolality is 150 mosmol/kg. In this setting, the daily urine volume will be 5 L if solute excretion is in the normal range at 750 mosmol/day, but only 3 L if solute excretion is lowered to 450 mosmol/day by dietary modification.

These observations provide the rationale for the use of a low-salt low-protein diet to diminish the urine output in NDI. The reduction in urine output will be directly proportional to the decrease in solute intake and excretion. Restriction of salt intake to ≤100 mEq/day (2.3 g sodium) and protein intake to ≤1.0 g/kg may be reasonable goals, but such diets are not easy to achieve and maintain. Furthermore, protein restriction in infants and young children may be harmful and is not advised. A thiazide diuretic (such as hydrochlorothiazide, 25 mg once or twice daily) acts by inducing mild volume depletion. As little as a 1–1.5 kg weight loss in adults with hereditary, NDI can reduce the urine output by >50% [e.g. from 10 to <3.5 L/day in a study of patients with NDI on a severely sodium-restricted diet (9 mEq/day)] [69, 70].

Acknowledgments

Funding. Canada Research Chair in Genetics of Renal Diseases to Dr. D. G. Bichet.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Estevez R, Boettger T, Stein V, et al. Barttin is a Cl- channel beta-subunit crucial for renal Cl- reabsorption and inner ear K+ secretion. Nature. 2001;414:558–561. doi: 10.1038/35107099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldegger S, Jeck N, Barth P, et al. Barttin increases surface expression and changes current properties of ClC-K channels. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeck N, Reinalter SC, Henne T, et al. Hypokalemic salt-losing tubulopathy with chronic renal failure and sensorineural deafness. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E5. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.1.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birkenhager R, Otto E, Schurmann MJ, et al. Mutation of BSND causes Bartter syndrome with sensorineural deafness and kidney failure. Nat Genet. 2001;29:310–314. doi: 10.1038/ng752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bettinelli A, Bianchetti MG, Girardin E, et al. Use of calcium excretion values to distinguish two forms of primary renal tubular hypokalemic alkalosis: Bartter and Gitelman syndromes. J Pediatr. 1992;120:38–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80594-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters M, Jeck N, Reinalter S, et al. Clinical presentation of genetically defined patients with hypokalemic salt-losing tubulopathies. Am J Med. 2002;112:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green ED, Guyer MS. Charting a course for genomic medicine from base pairs to bedside. Nature. 2011;470:204–213. doi: 10.1038/nature09764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bichet DG, Razi M, Lonergan M, et al. Hemodynamic and coagulation responses to 1-desamino[8-D-arginine]vasopressin (dDAVP) infusion in patients with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:881–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198804073181403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bichet DG, Razi M, Arthus M-F, et al. Epinephrine and dDAVP administration in patients with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Evidence for a pre-cyclic AMP V2 receptor defective mechanism. Kidney Int. 1989;36:859–866. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthus M-F, Lonergan M, Crumley MJ, et al. Report of 33 novel AVPR2 mutations and analysis of 117 families with X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1044–1054. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1161044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bichet DG, Hendy GN, Lonergan M, et al. X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: From the ship Hopewell to restriction fragment length polymorphism studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:1089–1102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birnbaumer M, Seibold A, Gilbert S, et al. Molecular cloning of the receptor for human antidiuretic hormone. Nature. 1992;357:333–335. doi: 10.1038/357333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal W, Seibold A, Antaramian A, et al. Molecular identification of the gene responsible for congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nature. 1992;359:233–235. doi: 10.1038/359233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner B, Seligsohn U, Hochberg Z. Normal response of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor to 1-deamino-8D-arginine vasopressin in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:191–193. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-1-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knoers N, Monnens LA. A variant of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: V2 receptor abnormality restricted to the kidney. Eur J Pediatr. 1991;150:370–373. doi: 10.1007/BF01955943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langley JM, Balfe JW, Selander T, et al. Autosomal recessive inheritance of vasopressin-resistant diabetes insipidus. Am J Med Genet. 1991;38:90–94. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320380120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deen PMT, Verdijk MAJ, Knoers NVAM, et al. Requirement of human renal water channel aquaporin-2 for vasopressin-dependent concentration of urine. Science. 1994;264:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8140421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ring AM, Cheng SX, Leng Q, et al. WNK4 regulates activity of the epithelial Na+ channel in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4020–4024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611727104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aidley DJ, Stanfield PR. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1996. Ion Channels: Molecules in Action. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agre P. Aquaporin water channels (Nobel Lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:4278–4290. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyon C, Lussier Y, Bissonnette P, et al. Characterization of D150E and G196D aquaporin-2 mutations responsible for nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: importance of a mild phenotype. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F489–F498. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90589.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leduc-Nadeau A, Lussier Y, Arthus MF, et al. New autosomal recessive mutations in aquaporin-2 causing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus through deficient targeting display normal expression in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2010;588:2205–2218. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fushimi K, Uchida S, Hara Y, et al. Cloning and expression of apical membrane water channel of rat kidney collecting tubule. Nature. 1993;361:549–552. doi: 10.1038/361549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin SH, Bichet DG, Sasaki S, et al. Two novel aquaporin-2 mutations responsible for congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in Chinese families. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2694–2700. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson GL, Kopp P. Global Conference Proceedings, NDI Foundation, April 26-28, 2002. 2002. A novel dominant mutation of the aquaporin-2 gene resulting in partial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus; p. 7A. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahakitrungruang T, Wacharasindhu S, Sinthuwiwat T, et al. Identification of two novel aquaporin-2 mutations in a Thai girl with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Endocrine. 2008;33:210–214. doi: 10.1007/s12020-008-9074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canfield MC, Tamarappoo BK, Moses AM, et al. Identification and characterization of aquaporin-2 water channel mutations causing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus with partial vasopressin response. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1865–1871. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.11.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marr N, Bichet DG, Hoefs S, et al. Cell-biologic and functional analyses of five new Aquaporin-2 missense mutations that cause recessive nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2267–2277. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000027355.41663.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller D, Marr N, Ankermann T, et al. Desmopressin for nocturnal enuresis in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Lancet. 2002;359:495–497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07667-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Lieburg AF, Verdijk MAJ, Knoers NVAM, et al. Patients with autosomal nephrogenic diabetes insipidus homozygous for mutations in the aquaporin 2 water-channel gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:648–652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulders SB, Knoers NVAM, van Lieburg AF, et al. New mutations in the AQP2 gene in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus resulting in functional but misrouted water channels. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:242–248. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V82242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheong HI, Park HW, Ha IS, et al. Six novel mutations in the vasopressin V2 receptor gene causing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nephron. 1997;75:431–437. doi: 10.1159/000189581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroll P, Al-Mojalli H, Al-Abbad A, et al. Novel mutations underlying nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in Arab families. Genet Med. 2006;8:443–447. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000223554.46981.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaki M, Schoneberg T, Al Ajrawi T, et al. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, thiazide treatment and renal cell carcinoma. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1082–1086. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goji K, Kuwahara M, Gu Y, et al. Novel mutations in aquaporin-2 gene in female siblings with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: evidence of disrupted water channel function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3205–3209. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuwahara M. Aquaporin-2, a vasopressin-sensitive water channel, and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Intern Med. 1998;37:215–217. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iolascon A, Aglio V, Tamma G, et al. Characterization of two novel missense mutations in the AQP2 gene causing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nephron Physiol. 2007;105:33–41. doi: 10.1159/000098136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vargas-Poussou R, Forestier L, Dautzenberg MD, et al. Mutations in the vasopressin V2 receptor and aquaporin-2 genes in 12 families with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1855–1862. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V8121855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boccalandro C, De Mattia F, Guo DC, et al. Characterization of an aquaporin-2 water channel gene mutation causing partial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in a Mexican family: evidence of increased frequency of the mutation in the town of origin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1223–1231. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000125248.85135.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Mattia F, Savelkoul PJ, Bichet DG, et al. A novel mechanism in recessive nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: wild-type aquaporin-2 rescues the apical membrane expression of intracellularly retained AQP2-P262L. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:3045–3056. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oksche A, Moller A, Dickson J, et al. Two novel mutations in the aquaporin-2 and the vasopressin V2 receptor genes in patients with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Hum Genet. 1996;98:587–589. doi: 10.1007/s004390050264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon SS, Kim HJ, Choi YK, et al. Novel mutation of aquaporin-2 gene in a patient with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Endocr J. 2009;56:905–910. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k09e-078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savelkoul PJ, De Mattia F, Li Y, et al. p.R254Q mutation in the aquaporin-2 water channel causing dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is due to a lack of arginine vasopressin-induced phosphorylation. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E891–E903. doi: 10.1002/humu.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Mattia F, Savelkoul PJ, Kamsteeg EJ, et al. Lack of arginine vasopressin-induced phosphorylation of aquaporin-2 mutant AQP2-R254L explains dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2872–2880. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mulders SM, Bichet DG, Rijss JPL, et al. An aquaporin-2 water channel mutant which causes autosomal dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is retained in the golgi complex. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:57–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamsteeg EJ, Wormhoudt TA, Rijss JP, et al. An impaired routing of wild-type aquaporin-2 after tetramerization with an aquaporin-2 mutant explains dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. EMBO J. 1999;18:2394–2400. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamsteeg EJ, Deen PM. Importance of aquaporin-2 expression levels in genotype -phenotype studies in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279:F778–F784. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.4.F778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamsteeg EJ, Stoffels M, Tamma G, et al. Repulsion between Lys258 and upstream arginines explains the missorting of the AQP2 mutant p.Glu258Lys in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:1387–1396. doi: 10.1002/humu.21068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bircan Z, Karacayir N, Cheong HI. A case of aquaporin 2 R85X mutation in a boy with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:663–665. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hochberg Z, van Lieburg A, Even L, et al. Autosomal recessive nephrogenic diabetes insipidus caused by an aquaporin-2 mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:686–689. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuwahara M, Iwai K, Ooeda T, et al. Three families with autosomal dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus caused by aquaporin-2 mutations in the C-terminus. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:738–748. doi: 10.1086/323643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohzeki T, Igarashi T, Okamoto A. Familial cases of congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus type II: remarkable increment of urinary adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate in response to antidiuretic hormone. J Pediatr. 1984;104:593–595. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marr N, Bichet DG, Lonergan M, et al. Heteroligomerization of an Aquaporin-2 mutant with wild-type Aquaporin-2 and their misrouting to late endosomes/lysosomes explains dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:779–789. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.7.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamsteeg EJ, Bichet DG, Konings IB, et al. Reversed polarized delivery of an aquaporin-2 mutant causes dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1099–1109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loonen AJ, Knoers NV, van Os CH, et al. Aquaporin 2 mutations in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Semin Nephrol. 2008;28:252–265. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sohara E, Rai T, Yang SS, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of autosomal-dominant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus caused by an aquaporin 2 mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14217–14222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602331103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tajkhorshid E, Nollert P, Jensen MO, et al. Control of the selectivity of the aquaporin water channel family by global orientational tuning. Science. 2002;296:525–530. doi: 10.1126/science.1067778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murata K, Mitsuoka K, Hirai T, et al. Structural determinants of water permeation through aquaporin-1. Nature. 2000;407:599–605. doi: 10.1038/35036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ragnarsson U. The Nobel trail of Vincent du Vigneaud. J Pept Sci. 2007;13:431–433. doi: 10.1002/psc.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seibold A, Brabet P, Rosenthal W, et al. Structure and chromosomal localization of the human antidiuretic hormone receptor gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:1078–1083. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raju TN. The Nobel chronicles. 1994: Alfred G Gilman (b 1941) and Martin Rodbell (1925-98) Lancet. 2000;355:2259. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)72762-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raju TN. The Nobel chronicles. 1971: Earl Wilbur Sutherland, Jr. (1915-74) Lancet. 1999;354:961. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)75718-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Capturing cyclic nucleotides in action: snapshots from crystallographic studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:63–73. doi: 10.1038/nrm2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nielsen S, Frokiaer J, Marples D, et al. Aquaporins in the kidney: from molecules to medicine. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:205–244. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boone M, Deen PM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the vasopressin-regulated renal water reabsorption. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456:1005–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0498-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nedvetsky PI, Tamma G, Beulshausen S, et al. Regulation of aquaporin-2 trafficking. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009:133–157. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79885-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morishita T, Tsutsui M, Shimokawa H, et al. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in mice lacking all nitric oxide synthase isoforms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10616–10621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502236102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olesen ET, Rutzler MR, Moeller HB, et al. Vasopressin-independent targeting of aquaporin-2 by selective E-prostanoid receptor agonists alleviates nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12949–12954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104691108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Earley LE, Orloff J. The mechanism of antidiuresis associated with the administration of hydrochlorothiazide to patients with vasopressin-resistant diabetes insipidus. J Clin Invest. 1962;41:1988–1997. doi: 10.1172/JCI104657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bichet DG. Clinical manifestations and causes of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. www.uptodate.com, UpToDate, 2011 (9 March 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]