Abstract

Goodpasture's (GP) disease is usually mediated by IgG autoantibodies. We describe a case of IgA-mediated GP, in a patient presenting with isolated rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. The diagnosis was established on kidney biopsy, since routine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) targeted at IgG circulating autoantibodies failed to detect the nephritogenic antibodies. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed intense linear deposition of IgA along the glomerular capillary walls. An elevated titre (1:80) of circulating IgA anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibodies was retrospectively demonstrated by indirect fluorescence. Despite immunosuppressive regimen, the disease progressed to end-stage renal failure (ESRF). Transplantation was not associated with recurrence in the kidney graft. We reviewed the 11 previously reported cases of IgA-mediated GP.

Keywords: anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, Goodpasture's disease, IgA

Background

Goodpasture's (GP) disease is an autoimmune condition responsible for rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis often accompanied by alveolar haemorrhage. It is mediated by autoantibodies directed against specific antigens of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), the noncollagenous-1 (NC1) domain of collagen IV chains α3 or α5 [1–2]. In most cases, the causative antibody is IgG. Early recognition relies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detecting circulating anti-GBM IgG antibodies in serum sample [3]. We describe a case of IgA-mediated GP, in which routine ELISA failed to detect the nephritogenic antibodies, and provide a review of prior cases.

Case report

A 49-year-old man was admitted to the renal unit for rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. His past medical history included chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3 due to left kidney agenesis (serum creatinine, 124 µmol/L; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by modification of diet in renal diseases 56 mL/min/1.73 m2) and smoking habit.

On admission, physical examination including blood pressure (120/70 mmHg) was normal. Serum creatinine had risen from 264 µmol/L to 539 µmol/L over the past 6 weeks. Urinary examination disclosed nephrotic range proteinuria (3.5 g/day) and microscopic haematuria, without anaemia. The routine ELISAs were negative for anti-GBM (Luminex, Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France), anti-nuclear antibodies and ANCA. Screening for a paraprotein was negative in serum and urine. There was no quantitative defect of IgG, IgA and IgM sub-classes. Computed tomography (CT) scan ruled out significant alveolar haemorrhage.

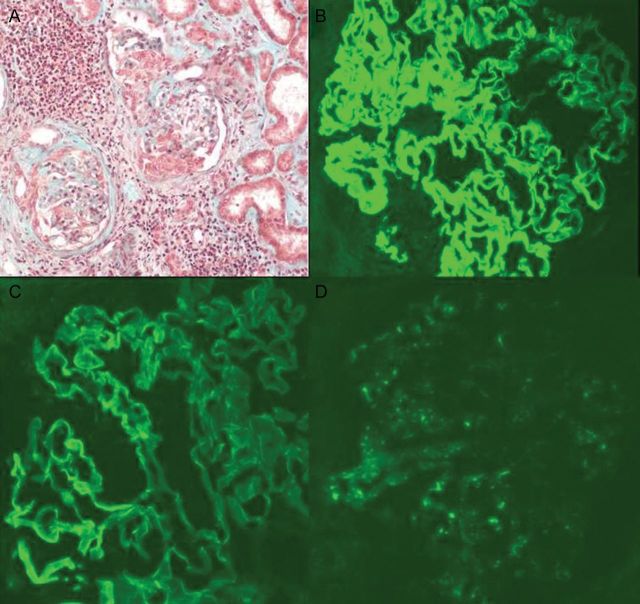

A kidney biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Pathological examination showed crescentic glomerulonephritis with both cellular and fibrocellular crescents and Bowman capsule's rupture. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed an intense linear deposition along the GBM with anti-alpha, anti-kappa and anti-lambda sera. Staining with anti-gamma revealed a similar but weak pattern. These results prompted us to check for circulating IgA anti-GBM: indirect fluorescence on macaque kidney slices using anti-IgA as secondary antibodies demonstrated circulating IgA anti-GBM antibodies. The titre was elevated at 1:80.

Fig. 1.

IgA-mediated anti-GBM disease. (A) Light microscopy: segmental crescentic glomerulonephritis. (B)–(D) Immunofluorescence microscopy: (B) intense and linear diffuse deposits along the GBM for IgA, (C) mild linear deposits along the GBM for IgG and (D) weak deposits with granular staining for C3.

In addition to daily plasma exchanges (PE), the patient was started on steroids (methylprednisolone, 1 mg/kg/day) and oral cyclophosphamide (CYC, 2 mg/kg/day). Despite this treatment and negative testing for circulating IgA anti-GBM after 14 PE, his renal function worsened rapidly and regular haemodialysis (HD) was started. The patient received a cadaveric kidney graft 18 months later. A transplant biopsy at month 5 revealed no recurrence of linear IgA deposits along the GBM in the immunofluorescence study. At last follow-up, his serum creatinine was 124 µmol/L.

Discussion

GP is a rare disease, with an incidence of one case/million inhabitants/year. It is characterized by a pulmonary-renal syndrome, which includes rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and alveolar haemorrhage. In approximately one-third of cases, there is no pulmonary involvement [1]. In a former study with an indirect immunofluorescence procedure, detection of antibodies in the serum proved negative in up to 40% of the cases. The development of sensitive and specific ELISA relying on the NC1 domain of the collagen IV α3 chain is much more reliable, with high specificity, and high titres of antibodies are detected in almost every patient with anti-GBM glomerulonephritis at the time of active disease, or even several months before the onset [4]. However, rare circulating anti-GBM antibodies may escape detection by ELISA or western blotting techniques, in renal patients and in isolated mild pulmonary disease. A highly sensitive device called highly sensitive biosensor could detect the culprit antibodies in two such cases [3]. In addition, since all these methods targeted IgG antibodies, rarely did the patients with IgA- or IgM-mediated GP disease remain unrecognized by serological testing.

IgA-mediated GP disease is very uncommon: in our renal unit, 33 patients with GP were diagnosed in the last decade (2000–2010). None except this case exhibited IgA-mediated disease. So far, only 11 cases have been reported in the literature [5–16]. Clinical and pathological findings are summarized in Table 1. In all but three cases, renal presentation was consistent with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Pulmonary involvement was found in only 4/10 cases. On kidney biopsy (10/11 patients), the percentage of crescentic glomeruli ranged from 6 to 75%. An immunofluorescence study demonstrated linear staining for IgA in all cases. Concomitant linear staining for IgG and C3 were reported, respectively, in one and two cases, while monotypic linear deposits of kappa or lambda light chains were found in one case each. Circulating IgA anti-GBM antibodies were detected in the nine patients in whom they were looked for. In our patient and a prior case [16], the kidney biopsy showed mild linear IgG deposits along the GBM, in addition to the intense IgA pattern. Mild linear IgG deposits along the GBM can be observed under various conditions (old age, diabetes mellitus, etc.), and should be interpreted in view of the clinical setting, as well as with regards to other immunological findings [3].

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological features in 12 reported cases of IgA-mediated GP diseasea

| Renal pathology |

Follow-up |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Age/gender | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | Serum IgA anti-GBM | % of crescents | Immunofluorescence (linear GBM deposits) | Alveolar haemorrhage | Initial treatment | Overall survival | Nephropathy |

| Borza et al. and Fervenza et al. [5, 6] | 54/M | 1.2 | Positive, monoclonal IgAκ | ? | IgA, κ | Yes | CS, CYC, PE | Censored at 8 years | ESRD at 5 years; KT → ESRD at 2 years |

| Maes et al. [7] | 67/M | 3.0 | Positive | ? | IgA, κ and λ | No | CS, CYC | Death (M1, aortic dissection) | Severe CKD |

| Carreras et al. [8] | 69/M | 3.8 | Positive | ? | IgA; κ, λ and C3 not specified | Yes | CS, IVIg | Death (D2, alveolar haemorrhage) | Severe CKD |

| Savage et al. [9] | ?/M | ? | Positive | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Shaer et al. [10] | 35/M | 20.0 | ? | ? | IgA, κ and λ | No | CS | Death (D20) | HD |

| Gris et al. [11] | 62/M | 9.0 | Positive, IgA1 | 67% | Polyclonal IgA, C3 | No | CS, AZA | Death (M23, stroke) | HD |

| Nakano et al. [12] | 43/M | ? | ? | 75% | IgA; C3 not specified | Yes | CS | Death (M13, sepsis) | Moderate CKD |

| de Caestecker et al. [13] | 55/M | 0.9 | Positive | 6% | IgA; κ/λ not specified | No | ? | Censored at M36 | Normal |

| Border et al. [14] | 55/M | Normal | Positive | 10% | Anti-α | Yes | CS, AZA, PE | Death (M24, alveolar haemorrhage) | Severe CKD |

| Ho et al. [15] | 74/F | 1.2 | Positive | >40% | IgA, λ | No | CS, CYC | Censored at M4 | Moderate CKD |

| Ghohestani et al. [16] | 72/M | 5.6 | Positive | 75% | IgA (3+), IgG (+), C3(+) | No | CS, CYC, PE | Censored at M6 | HD |

| Present case | 49/M | 6.1 | Positive | >25% | IgA (3+), IgG (+), C3 (+) | No | CS, CYC, PE | Censored at M30 | HD, then KT |

aAZA, azathioprine; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CS, corticosteroids; CYC, cyclophosphamide; D, day; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; HD, haemodialysis; PE, plasma exchanges; M, month; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; KT, kidney transplantation.

Kidney biopsy is the primary test used to recognize IgA-mediated GP. Its usefulness was reinforced by reports of four patients with prior histories of other autoimmune diseases, i.e.: Henoch–Schonlein purpura [8], Crohn's disease [10], systemic lupus erythematosus [15] and autoimmune bullous dermatitis [16]. When compared with patients with classical IgG-related GP, the prognosis of IgA-related GP is poor (Table 1): among nine patients presenting with renal failure, none improved; within 6 months follow-up, two patients died of uncontrolled alveolar haemorrhage. At last follow-up, 5/10 patients were in end-stage renal failure (ESRF). Whether the classical triple regimen used in IgG-mediated GP (PE, steroids and oralCYC) is optimal in IgA-mediated GP is unknown. This approach was used in only 3/11 IgA-mediated GP patients. All of them progressed to ESRF.

The pathophysiology of IgA-mediated GP is not entirely understood. In contrast with IgG-mediated GP, the autoantigen might prove more to be heterogeneous: it belonged to α5 and α6 chains of type IV collagen in the case described by Ghohestani et al. [16]; in the observation reported by Borza et al., the autoantibody was a monoclonal IgAκ directed against type IV collagen chains α1, and α2 and was responsible for relapse after renal transplantation [5–6]. This form of monotypic IgA-related condition should be considered a different disease, when compared with patients without a monoclonal component. In our case, the specificity of the antibody epitopes was not assessed.

In summary, IgA-mediated GP is extremely rare. Pathogenic autoantibodies cannot be detected by routine ELISA profiled to detect IgG circulating autoantibodies. Recognition relies on immunofluorescence microscopy of the kidney biopsy. Despite intensive therapy modeled on IgG-mediated GP, the renal prognosis is poor. Kidney transplantation is an option for ESRF.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared. (See related Editorial comment by A.S. Bomback. Anti-glomerular basement membrane nephritis: why we still ‘need’ the kidney biopsy. Clin Kidney J 2012; 5: 496–497)

References

- 1.Turner AN, Rees AJ. Antiglomerular basement disease. In: Davison A, Stewart Cameron J, Grunfeld JP, et al., editors. Oxford Textbook of Clinical Nephrology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 579–595. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedchenko V, Bondar O, Fogo AB, et al. Molecular architecture of the Goodpasture autoantigen in anti-GBM nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:343–354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salama AD, Dougan T, Levy JB, et al. Goodpasture's disease in the absence of circulating anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies as detected by standard techniques. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:1162–1167. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen SW, Arbogast CB, Baker TP, et al. Asymptomatic autoantibodies associate with future anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1946–1952. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010090928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borza DB, Chedid MF, Colon S, et al. Recurrent Goodpasture's disease secondary to a monoclonal IgA1-kappa antibody autoreactive with the alpha1/alpha2 chains of type IV collagen. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:397–406. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fervenza FC, Terreros D, Boutaud A, et al. Recurrent Goodpasture's disease due to a monoclonal IgA-kappa circulating antibody. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maes B, Vanwalleghem J, Kuypers D, et al. IgA antiglomerular basement membrane disease associated with bronchial carcinoma and monoclonal gammopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:E3. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carreras L, Poveda R, Bas J, et al. Goodpasture syndrome during the course of a Schönlein–Henoch purpura. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:E21. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savage CO, Pusey CD, Bowman C, et al. Antiglomerular basement membrane antibody mediated disease in the British Isles 1980–1984. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:301–304. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6516.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaer AJ, Stewart LR, Cheek DE, et al. IgA antiglomerular basement membrane nephritis associated with Crohn's disease: a case report and review of glomerulonephritis in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1097–1109. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gris P, Pirson Y, Hamels J, et al. Antiglomerular basement membrane nephritis induced by IgA1 antibodies. Nephron. 1991;58:418–424. doi: 10.1159/000186473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakano H, Suzuki A, Tojima H, et al. A case of Goodpasture's syndrome with IgA antibasement membrane antibody. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;28:634–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Caestecker MP, Hall CL, MacIver AG. Atypical antiglomerular basement membrane disease associated with thin membrane nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1990;5:909–913. doi: 10.1093/ndt/5.11.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Border WA, Baehler RW, Bathena D, Glassock RJ. IgA anti-basement membrane nephritis with pulmonary hemorrage. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:21–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho J, Gibson IW, Zacharias J, et al. Antigenic heterogeneity of anti-GBM disease: new renal targets of IgA autoantibodies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:761–765. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghohestani RF, Rotunda SL, Hudson B, et al. Crescentic glomerulonephritis and subepidermal blisters with autoantibodies to alpha5 and alpha6 chains of type IV collagen. Lab Invest. 2003;85:605–611. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000067497.86646.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]