Abstract

Objective

To produce an expert consensus hierarchy of harm to self and others from legal and illegal substance use.

Design

Structured questionnaire with nine scored categories of harm for 19 different commonly used substances.

Setting/participants

292 clinical experts from across Scotland.

Results

There was no stepped categorical distinction in harm between the different legal and illegal substances. Heroin was viewed as the most harmful, and cannabis the least harmful of the substances studied. Alcohol was ranked as the fourth most harmful substance, with alcohol, nicotine and volatile solvents being viewed as more harmful than some class A drugs.

Conclusions

The harm rankings of 19 commonly used substances did not match the A, B, C classification under the Misuse of Drugs Act. The legality of a substance of misuse is not correlated with its perceived harm. These results could inform any legal review of drug misuse and help shape public health policy and practice.

Article summary

Article focus

To produce an expert-based consensus on the relative harms posed by 19 commonly used legal and illegal substances.

Key messages

The legality of a substance is not correlated with its perceived harm. There is no stepped ‘A, B, C’ distinction in harm evident.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is largest known addiction experts survey of substance-related harm. Observer bias cannot be excluded The availability and cost of substances was not taken into account.

Introduction

Drug and alcohol misuse is a significant and growing problem in Scotland. The levels of problematic drug misuse are double that of England, and alcohol dependency is a third higher than other parts of the UK. Drug- and alcohol-related deaths are among the highest in Europe and have doubled over the past 15 years.1 In 2007, it was estimated that the alcohol industry was worth around £3.5 billion2 and that the largest part of the informal Scottish economy was made up from the trade of illicit drugs. In the UK, as a whole, the total cost burden of drug misuse is estimated to be between £10 billion and £16 billion per year.3

The laws regulating drug use are complicated. The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 defines what are termed ‘controlled drugs’, dividing illicit drugs into three categories—A, B, and C—which were designed to reflect the harm caused to both the individual and society generally by these drugs (see table 1). Drugs classified as causing the most severe harm are designated class A and include heroin, cocaine and ecstasy. The law thus implies that class A drugs are the most dangerous of all. Class B is thought to be less harmful than class A, but more harmful than class C and contains amphetamines and barbiturates. Class C includes cannabis and benzodiazepine tranquillisers. This categorical classification system does not include two commonly used and powerful psychoactive drugs, tobacco and alcohol, which are legal to use for those older than 18 years in the UK.

Table 1.

Substances chosen for study and comparison

| Substance | Class in Misuse of Drugs Act at time of data collection |

| Alcohol | Not controlled if over 18 years |

| Amphetamines | B |

| Barbiturates | B |

| Benzodiazepine | C |

| Buprenorphine/Temgesic | C |

| Cannabis | B |

| Cocaine | A |

| Crack cocaine | A |

| Crystal meth | A |

| Dihydrocodeine/codeine/Tramadol | Not controlled |

| Ecstacy/MDTA | A |

| Heroin | A |

| Ketamine | C |

| LSD | A |

| Magic mushrooms | A |

| Methadone | A |

| Nicotine/tobacco | Not controlled if over 18 years |

| Methylphenidate/Ritalin | B |

| Inhaled solvents | Not controlled |

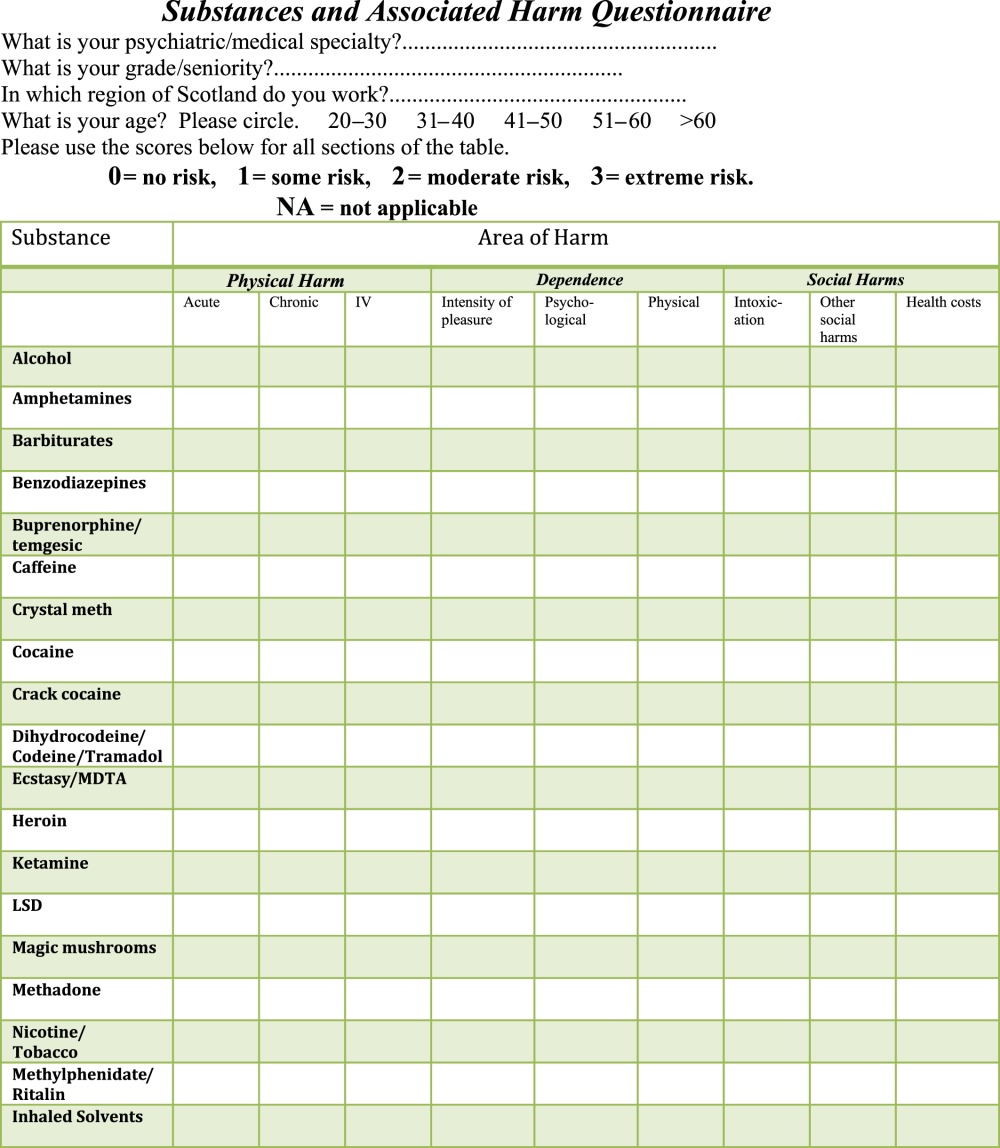

It has been argued over recent years that this classification has become outdated and only modestly correlates with expert ratings of harm caused by the various substances. In 2007, Nutt et al 4 attempted to reassess the system of drug classification and produce a more contemporary hierarchy of harm. UK experts in psychiatry, addictions and pharmacology were asked to rate drugs on three major dimensions of harm: physical harm, potential for dependence and social harms. Under the physical harm dimension, they were asked to score three different components: the acute effects and harm to health, the chronic harm to health and the harm to physical health caused by intravenous drug use. Under the dependence dimension, three further components were rated, namely the intensity of pleasure produced by the drug, the psychological dependence and the potential physical symptoms of dependence related to the specific substance. In the final dimension of social harm, the components rated were harms to others caused by intoxication; health costs directly resulting from the drug use, including the costs to healthcare and social care systems; and finally, other social harms, such as violent behaviour, neglect of children and financial problems caused by drug use. The aim of this study was to obtain a comprehensive consensus from addiction experts in Scotland on the relative harms of drug misuse, both legal and illegal using the ranking system developed by Nutt et al.4

Methods

Nutt et al 4 designed a matrix that included three major categories of harm with each category being subdivided into three groups, producing nine parameters of risk. This nine-parameter scale was adapted (see appendix) to produce a questionnaire to assess physical and psychological harm to self and others for 19 commonly used legal and illegal substances. The nine parameters were (a) physical harm caused by acute, chronic and parenteral use; (b) psychological harm; physical harm and intensity of pleasure linked to dependence and (c) social harm from intoxication; other social harms and associated healthcare costs.

The 19 substances chosen for assessment are shown in table 1, along with their status under the Misuse of Drugs Act at the time of this study.

Addiction specialists and psychiatrists working with substance misuse across Scotland were approached to complete the questionnaire, on the basis of their clinical experience and expertise. This was mainly by face-to-face interviews, with personal interviews being arranged via local regional addictions teams across the country (see the Results section for more details). Approximately 300 individuals working in multidisciplinary addiction teams across Scotland were approached to undertake face-to-face interviews, for completion of the questionnaire, and were chosen via the authors' knowledge of and contact with local addiction services. The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland database of psychiatrists who have a special interest in addictions (approximately 200 individuals in total) was also used to elicit completed responses via email. The number of experts approached was not prospectively determined beyond seeking as large a sample size as possible—no a priori sample size was chosen.

Guidance notes on how to complete the questionnaire were also issued, and during the face-to-face interviews, there was explicit guidance provided emphasising that the harm rankings should be based on the experts' global clinical experience of the population seen in addictions services (ie, not based on an understanding of ‘milder’ wider society use patterns). Participants were asked to score each substance for each of the nine parameters, using a 4-point scale, with 0 being no risk, 1 some risk, 2 moderate risk and 3 extreme risk.

Basic demographic information about the respondents was also recorded, including region of Scotland where they worked, specialty area of work, job title and age. No financial or other incentive was offered to respondents.

Analysis

Scores were averaged for each parameter. For some analyses, the scores for the three parameters for each category were averaged to give a mean score for that category, that is, an overall score for harm to self and overall score for harm to others. An overall harm rating was obtained by taking the mean of all nine scores.

Results

Demographics of respondents

Two hundred and ninety-two completed responses were obtained from seven different regions in Scotland. Fifty per cent of respondents worked in the Glasgow region, with 15% working in Tayside, 13% in Grampian, 11% in Forth Valley and 9% in Lothian and Borders. One per cent worked in Lanarkshire, and 1% of responses had not recorded their region. Fewer than 10 psychiatrists from the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland database submitted a completed response online. Over 90% of those directly approached for face-to-face interviews agreed to participate, whereas the response rate to email requests for questionnaire completion was <5%, perhaps reflecting that on average 30 min was required to complete each questionnaire.

Respondents were from a range of professional backgrounds in health and social work. They worked across a variety of specialties with addictions being most represented with 64% of respondents. 18.5% worked in the General Adult Psychiatry setting and 0.5% worked in Forensic Psychiatry. Sixteen per cent worked in other areas such as General Practice, and 1% of respondents had not recorded their specialty (see table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical experts' professional background

| Job title | Frequency | Per cent |

| Consultant psychiatrist | 24 | 8.2 |

| Specialist registrar | 15 | 5.1 |

| SHO/staff grade | 23 | 7.9 |

| General practitioner | 6 | 2.1 |

| Addiction community psychiatric nurse | 133 | 45.5 |

| Addiction worker | 39 | 13.4 |

| Social worker | 52 | 17.8 |

| Total | 292 | 100 |

SHO, junior doctor.

The age of respondents ranged from 20 to older than 60 years. The largest groups were the 31–40 years with 38.5% and the 41–50 years with 38%. Ten per cent of responses came from workers aged 20–30 years and 9% from those aged 51–60 years. Four per cent of respondents were aged older than 60 years and 0.5 had not recorded their age. Addiction community psychiatric nurses were easily the biggest single professional discipline, reflecting the composition of a typical community addictions team, and they on average had over 5 years clinical experience in the field.

Harm rankings

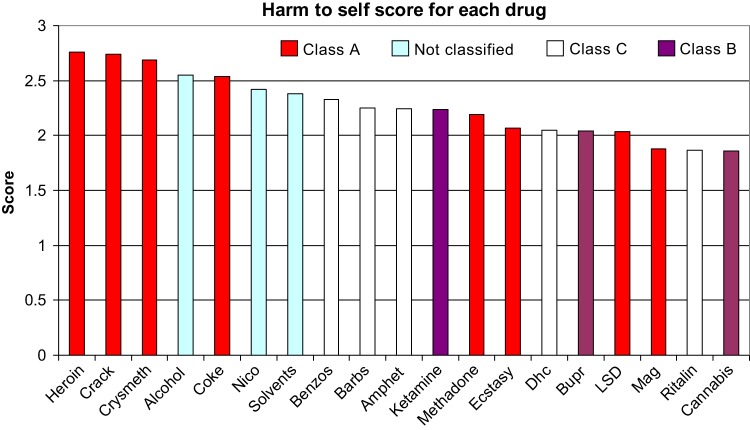

The mean scores for the substances assessed are shown in table 3. Table 3 lists the results for each of the three subcategories of harm. The scores in each category were averaged across all scorers, and the substances are listed in rank order of harm based on their overall score. Many of the drugs were consistent in their ranking across the three categories.

Table 3.

Assessment score tables

| Substance | Personal harm score | Social harm score | Total/combined harm score |

| Heroin | 2.76 | 2.72 | 2.74 |

| Crack cocaine | 2.74 | 2.60 | 2.69 |

| Crystal meth | 2.69 | 2.54 | 2.63 |

| Alcohol | 2.55 | 2.70 | 2.56 |

| Cocaine | 2.54 | 2.33 | 2.46 |

| Inhaled solvents | 2.38 | 2.18 | 2.31 |

| Nicotine | 2.42 | 2.23 | 2.29 |

| Benzodiazepines | 2.33 | 2.17 | 2.27 |

| Ketamine | 2.24 | 1.97 | 2.13 |

| Barbiturates | 2.25 | 1.91 | 2.12 |

| Amphetamine | 2.24 | 1.89 | 2.11 |

| Methadone | 2.19 | 1.96 | 2.10 |

| Dihydrocodeine/codeine/Tramadol | 2.05 | 1.89 | 1.98 |

| Buprenorphine | 2.04 | 1.83 | 1.96 |

| LSD | 2.04 | 1.87 | 1.95 |

| Ecstasy/MDTA | 2.07 | 1.74 | 1.92 |

| Methylphenidate/Ritalin | 1.86 | 1.62 | 1.74 |

| Magic mushrooms | 1.88 | 1.60 | 1.74 |

| Cannabis | 1.86 | 1.61 | 1.73 |

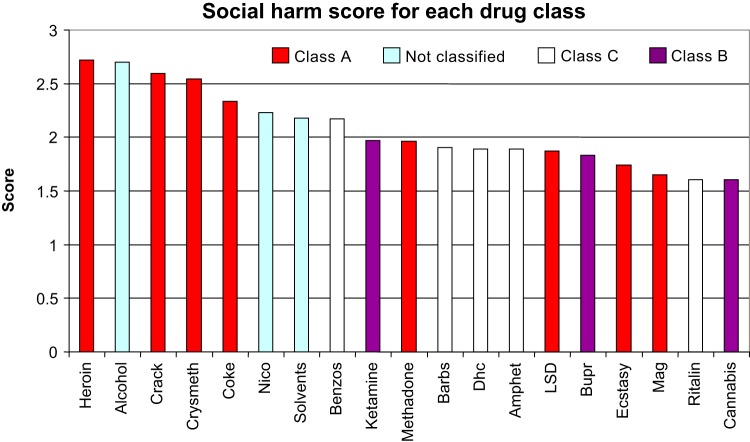

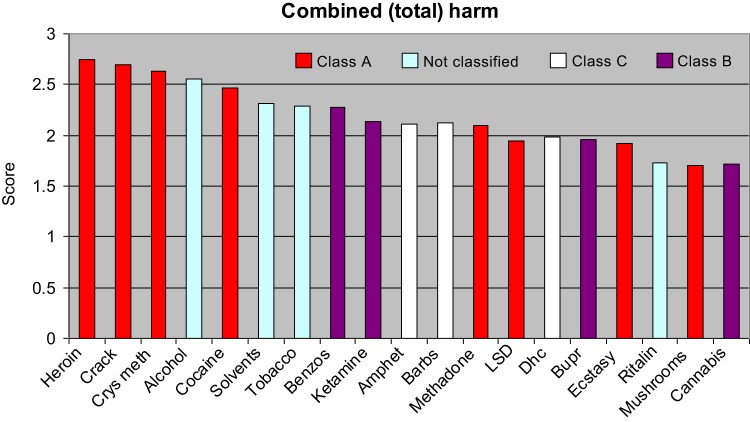

Heroin, crack cocaine, crystal meth, alcohol and cocaine were in the top five places for all categories of harm.

LSD, ecstasy, methylphenidate, magic mushrooms and cannabis were in the bottom five places for all categories of harm. Cannabis was rated as the least harmful drug.

Alcohol was the only drug that rated more highly on the social harm score than on personal harm. Alcohol was rated fourth and nicotine was seventh across all categories of harm ranking higher than some controlled drugs.

Figures 1–3 are the diagrammatic representations of the scores for each drug across the harm categories. The colour coding equates to the drug's status under the Misuse of Drugs Act at the time of data collection.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of the ranking of personal harm scores for each drug.

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic representation of the ranking of social harm scores for each drug.

Figure 3.

Diagrammatic representation of the ranking of combined scores for harm.

Discussion

The main outcome of this study is a ranking by Scottish addiction experts of 19 recreational drugs according to their mean harm score. The main result is that heroin, crack cocaine, crystal meth, alcohol and cocaine were in the top five places for all categories of harm, with LSD, ecstasy, methylphenidate, magic mushrooms and cannabis in the bottom five places for all categories of harm. Notably, legal substances such as alcohol, nicotine and volatile agents ranked as more harmful than some class A drugs, although these drugs are more socially and culturally embedded in Scotland than the prohibited ones. The hierarchy of harm when judged by the experts did not correlate with the hierarchy used currently by the Misuse of Drugs Act. There is no indication of a stepwise reduction in harm as would be supposed by the current A, B, C classification and no clear delineation of scores to allow logical cut-off points for such a categorisation. These results are similar to Nutt's original work and to a more recent Dutch study,5 which used the same scoring system but different methodology to this study. Nutt et al 4 confirmed that the sharp A, B or C division of the current classification in the UK Misuse of Drugs Act did not correlate with the rankings of harm by the experts, and the experts showed reasonable levels of agreement in their rankings, leading to a proposal that their rating system could be developed by regulatory bodies to provide an evidence-based approach to drug classification.

One of the strengths of this study is the large number of experts involved. Two hundred and ninety-two addiction multidisciplinary experts across Scotland were involved making it the largest national panel to be involved in this type of study. This large number of multidisciplinary expert respondents might also help reduce any selection and observer bias in the sample, although it is acknowledged that the expert clinician respondents were chosen on an ad hoc rather than systematic basis. We obtained a high response rate for this survey, but it is possible that addiction specialists from geographic areas that were not approached (eg, NHS Fife) might have reported different results, and thus response bias cannot be excluded despite the sample size. A recognised weakness is that the scale used to obtain the harm scores is not ideal as it does not examine all the conceivable ways in which a substance may cause harm and is limited to nine criteria. Also although the physical harm of drugs tends to be well defined, that is, acute and chronic toxicity and addictive potency, in contrast the spectrum of social harm tends to be rather less so which may hamper the objective rating of the social harms for drugs. Some of the social harms, which are applicable to one drug, may not necessarily be transferrable to another drug, which has different properties, for example, sedative versus stimulant. There is no method of applying a differential weighting to each parameter of harm, and it is clear that some criteria are more important expressions of harm than others. Nutt et al 6 attempted to address these issues using multicriterion decision analysis, with 16 criteria for rating harm and a weighting score out of 100 for each criterion. This approach increased the differentiation between the most and least harmful drugs, and here alcohol rated as the most harmful with heroin second and tobacco sixth. A problem with this format of harm ratings is that it does not take account of availability of the substance in question, for example, that alcohol might be highly ranked due to its low cost and widespread availability. It is also recognised that caution must be taken in making comparisons between legal substances and illegal ones as substances such as alcohol, nicotine and volatile agents are far more widely available, arguably particularly affecting social harm. Another limitation of the present study is that our scale measures only harm and does not look at perceived or actual benefits to the user, which motivated the use in the first place.

The high rankings of alcohol and tobacco in this study reflect the common recognition that chronic use of alcohol and tobacco cause illness and death, contributing to 90% of drug-related deaths in the UK. Every year in the UK, tobacco smoking causes around 100 000 premature deaths, reducing average life expectancy in regular smokers by 10 years,7 with population-based studies suggest that smoked tobacco is the most addictive commonly used drug. Alcohol is a growing problem in Scotland where there is one of the fastest growing rates of liver cirrhosis in the world, having doubled since 1990 and being twice that of England and Wales.8 Alcohol misuse is also known to be a risk factor for suicide, and the National Confidential Inquiry9 into suicides indicated that 58% of individuals dying by suicide in Scotland had a history of alcohol misuse and in 17% alcohol dependence was the primary diagnosis. The report also shows that there is a substantially higher rate of homicides and suicides in Scotland compared with England and Wales, which can be largely attributed to high levels of alcohol and drug misuse, both in the general population and among people with mental health problems. Cause and effect cannot be attributed here though, as the pathways to suicide and to homicide are complex and multiple. In this study, alcohol was the only drug to rate higher on social harm than personal harm reflecting the enormous burden to the healthcare system posed by alcohol and also the negative effects on rates of crime, work place absences and on family life including domestic violence.

Interestingly, cannabis was ranked as the least harmful drug by the Scottish addiction experts. This differs from both Nutt's work and the Dutch study where it was ranked as 11th and 12th, respectively. It is not clear why there would be such a variation in scores for cannabis, although at the time of survey the use of high potency cannabis was not yet widespread in Scotland. One reason may be the differences in the panel of experts. Our study examined the views of clinicians and addiction workers, whereas the other panels included toxicologists, pharmacists and experts from a legal background who would have a different experience of working with cannabis. Other explanations may be that despite cannabis being commonly used in Scotland, individuals who misuse cannabis present less frequently requesting help to addiction services than with other drugs of abuse and that addictions specialists do not usually see cannabis addiction with comorbid psychotic illness and how can one exacerbate the other.

Alcohol and drug misuse is an immense and highly complex challenge for policymakers in Scotland. Historically, illicit drug misuse has been linked with the criminal justice system and the system of classification currently in use reflects this. This study demonstrates, similar to both of Nutt's studies, that the legality of a substance does not reflect its potential for harm. Just because a substance is legal, it does not mean that it is safe to use. This has been highlighted recently with the reclassification of some of the so-called ‘legal highs’. Recent work looking a mephedrone in particular have shown that it has a considerable harm profile to both physical10 and mental health11 and that making a substance illegal does not necessarily reduce its usage and may only act to drive up the price.12 The burgeoning evidence of the harm caused by tobacco and alcohol would also suggest that from a scientific perspective these drugs are currently misclassified and that a new method for ranking drug harm, which could guide policies and public health strategies, is required, with many in the scientific and medical community feeling that this should be separated from the criminal justice system and associated penalties. Any new system would also have to address the issue of personal choice and responsibility in using substances and examine the context in which they are being used. Increasing public awareness of the potential for harm of all the drugs examined whether legal or illegal and finding ways of reducing the demand for psychoactive substances should be the focus rather than imposing harsh penalties for their use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the addiction experts surveyed for volunteering their time.

Appendix.

|

Footnotes

To cite: Taylor M, Mackay K, Murphy J, et al. Quantifying the RR of harm to self and others from substance misuse: results from a survey of clinical experts across Scotland. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000774. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000774

Contributors: MT and JM conceived and designed the study. All authors except KM and AM collected the data. AM helped analyse the results. All authors were involved in interpreting the results, drafting the paper and approving the final manuscript. All authors had full access to all data and can take responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the data. MT is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: The research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors are employed by NHS Scotland except AM who is an employee of the University of Edinburgh. These employers were not involved in the data collection or interpretation of results.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The raw data are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Drug and Alcohol Services in Scotland. A Report by Audit Scotland. 2009. http://www.auditscotland.gov.uk (accessed Dec 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 2. NHS National Services Scotland. Alcohol Statistics Scotland 2007. 2007. http://www.alcoholinformation.isdscotland.org (accessed Dec 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Foresight. Brain Science, Addiction and Drugs. 2005. http://www.foresight.gov.uk/Brain_Science_Addiction_and Drugs/index.html (accessed Nov 2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, et al. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet 2007;369:1047–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Amsterdam JG, Opperhuizen A, Koeter M, et al. Ranking the harm of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs for the individual and the population. Eur Addict Res 2010;16:202–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nutt D, King LA, Phillips L. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. Lancet 2010;376:1158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Britton J, McNeill A, Arnott D, et al. Drugs and harm to society. Lancet 2011;377:551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alcohol Summit. Scottish Government News Release 2009. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/News/Releases/2009/06/22102738 (accessed Nov 2011).

- 9. The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness. University of Manchester, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wood DM, Greene SL, Dargan PI. Clinical pattern of toxicity associated with the novel synthetic cathinone mephedrone. Emerg Med J 2011;28:280–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mackay K, Taylor M, Bajaj N. The adverse consequences of mephedrone use: a case series. Psychiatrist 2011;35:203–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winstock L, Mitcheson J, Marsden C. Mephedrone: still available and twice the price. Lancet 2010;376:1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]