Abstract

Objectives

To compare the features of relapse, morbidity, mortality and re-hospitalisation following successful discharge after severe pneumonia in children between a day care group and a hospital group and to explore the predictors of failures during 3 months of follow-up.

Design

An observational study following two cohorts of children with severe pneumonia for 3 months after discharge from hospital/clinic.

Setting

Day care was provided at the Radda Clinic and hospital care at a hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Participants

Children aged 2–59 months with severe pneumonia attending the clinic/hospital who survived to discharge.

Intervention

No intervention was done except providing some medications for minor illnesses, if indicated.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were the proportion of successes and failures of day care at follow-up visits as determined by estimating the OR with 95% CI in comparison to hospital care.

Results

The authors enrolled 360 children with a mean (SD) age of 8 (7) months, 81% were infants and 61% were men. The follow-up compliance dropped from 95% at first to 85% at sixth visit. The common morbidities during the follow-up period included cough (28%), fever (17%), diarrhoea (9%) and rapid breathing (7%). During the follow-up period, significantly more day care children (n=22 (OR 12.2 (95% CI 8.2–17.8))) required re-hospitalisation after completion of initial day care compared with initial hospital care group (n=11 (OR 6.1 (95% CI 3.4–10.6))). The predictors for failure were associated with tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypoxaemia on admission and prolonged duration of stay.

Conclusions

There are considerable morbidities in children discharged following treatment of severe pneumonia like cough, fever, rapid breathing and diarrhoea during 3-month period. The findings indicate the importance of follow-up for early detection of medical problems and their management to reduce the risk of death. Establishment of an effective community follow-up would be ideal to address the problem of ‘non-compliance with follow-up’.

Trial registration

The original randomised control trial comparing day care with hospital care was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00455468).

Article summary

Article focus

The main focus of the article is to describe the features of relapse, morbidity, mortality and re-hospitalisation following successful discharge for severe pneumonia in <5-year-old children in urban Dhaka, Bangladesh.

To compare the compliance, relapse, morbidity, mortality and re-hospitalisation rates between an outpatient-managed day care group and a hospital-managed group over 3 months.

To identify the predictors for treatment failure.

Key messages

The compliance with follow-up visits after discharge from the clinic/hospital gradually reduced over time following discharge: 95% for the first to 85% for the sixth visit.

Children following apparently effective treatment of severe pneumonia experienced considerable morbidities due to cough, fever, diarrhoea and rapid breathing during 3-month follow-up with significantly higher number of hospital care children reported cough, diarrhoea and feeding difficulty compared with day care children.

The predictors for treatment failure were associated with tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypoxaemia on admission and prolonged duration of stay; follow-up of children with severe pneumonia is very important for early detection of medical problems for reducing the risk of morbidity and death.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Although the follow-up compliance reduced over time, it was still impressive (85%) even at the end of 3 months. Moreover, this impressive rate of follow-up was spontaneous, around 95% of the children were brought by their parents and no incentives were given. The identification of predictors for failure including the presence of tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypoxaemia on admission and prolonged duration of clinic/hospital stay are very important strengths of the study. The number of minor illnesses developed during the follow-up period was low (only 14%) and the requirement for medication following recovery was also low (19%).

There were some important limitations in this study. First, we could not assess sustainability of 3-month follow-up visits at the respective healthcare facilities where children had received their initial treatment. Second, we did not assess the feasibility of community follow-up, which can be done in future studies.

Introduction

Pneumonia is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in under-5 children causing about 1.6 million deaths every year globally.1 According to a recent report published in 2010, 18% of the total 8.8 million global deaths among under-5 children in 2008 were due to pneumonia.1 There is an estimated incidence of 151 million new cases of childhood pneumonia each year globally, including 61 million cases in southeast Asia, and 11–20 million (7%–13%) are severe enough to require hospitalisation in developing countries.2–4 An estimated 1.9 million children died from acute respiratory infection globally in 2000 and 70% of these deaths occurred in Africa and Southeast Asia.5 6 In Bangladesh, acute lower respiratory infection accounts for 25% of <5-year-old child deaths and 40% of infantile deaths.7 Recent reports have shown that pneumonia accounts for about 14% and 12% deaths from community-based1 and hospital-based studies8 of <5-year-old child in Bangladesh, respectively. Although community case management of non-severe pneumonia9 as well as severe pneumonia by lady health worker with oral antibiotics10 and ambulatory home treatment with high-dose oral amoxicillin11 has been reported from Pakistan, the WHO's guidelines for case management of pneumonia still recommend that children with severe pneumonia require facility-based management with parenteral antibiotics12 but an inadequate number of paediatric beds limits hospital care in Bangladesh. This inadequate capacity assuredly results in excess and unnecessary death of children, who, with proper care, would otherwise survive. We, therefore, developed the concept of a ‘day care’ model13–16 through establishment of facilities at ‘outpatient clinics’ for management of common childhood illnesses, such as severe acute malnutrition13 and severe pneumonia,14 15 hoping to provide greater curative or case management benefits to Bangladeshi children and thus reducing morbidity and deaths, the results of which demonstrated that it is possible to successfully manage childhood pneumonia with antibiotics, feeding and supportive care for a week.14 15 However, there is little information about what happens after recovery from pneumonia and whether this recovery is sustained in their homes over a longer period. Short-term successes, if not sustained, and/or if associated with higher rates of relapse or recurrence or death would not be acceptable as a public health intervention. The reasons for death, or relapse or other morbidities need to be understood, and deaths are likely when medical care and treatment are inaccessible. Therefore, we described the novelty of the current observational study by comparing 3 months outcomes post-discharge and also by providing some limited data on the morbidity and mortality for severe pneumonia post-discharge.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were (1) to describe the features of relapse, morbidity, mortality and re-hospitalisation following successful discharge after severe pneumonia in <5-year-old children in urban Dhaka, Bangladesh; (2) to compare the compliance, relapse, morbidity, mortality and re-hospitalisation rates between an outpatient-managed day care group and a hospital-managed group over 3 months and (3) to explore the predictors of treatment failures for 3 months of follow-up.

Study design

An observational study following two cohorts of children with severe pneumonia who were discharged either from the outpatient day care clinic or from the hospital after recovery from their primary illness during the long-term post-management follow-up of children enrolled in another randomised controlled trial.15

Settings

The day care was provided at the Radda Clinic and the hospital care was provided at the Institute of Child Health and Shishu Sasthya Foundation Hospital (ICHSH), both located at Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh. For the follow-up study, the Radda Clinic remained open from 08:00 to 17:00 h on each day including the weekends and holidays, but the hospital remained open for 24 h. Mothers usually came for follow-up visits during the morning hours between 09:00 and 12:00, but only few came in the afternoon. All the project staff including study physicians, nurses and healthcare workers remained available at the clinic and hospital during the above opening hours for conducting other ongoing projects during that period, and they were also routinely performing the follow-up visits.

Participants

In the above-mentioned original reference study,15 we compared the outpatient day care management with inpatient hospitalised management of children of either sex, aged 2–59 months, with severe pneumonia according to the WHO criteria.12 From September 2006 through November 2008, they were randomised to receive day care management at a clinic or hospitalised management and then followed up for 3 months after discharge. The original study15 including the follow-up was approved by the Research and Ethical Review Committees of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh. A written informed consent including the 3-month follow-up after discharge was obtained from the parents of each child before enrolment into the study.

Follow-up study

After successful day care/hospital care management at the Radda Clinic/ICHSH with antibiotics, food and supportive care, children were discharged,15 while the study physicians mentioned all the dates for scheduled follow-up visits for the next 3 months in the discharge certificate and parents were advised to visit the respective clinic or hospital for follow-up assessment every 2 weeks for 3 months. At each follow-up visit, the study physician enquired the attending mothers/care givers about the signs and symptoms of specific morbidities since the previous visit. Morbidity data like respiratory (eg, cough, fever, running nose, difficulty in breathing, chest indrawing, rales on auscultation), diarrhoeal or others (eg, eye, ear, nose and skin infection, thrush, passage of worms) were recorded on a case report form. The vital signs (pulse, respiration, temperature, body weight, length/height and oxygen saturation) were recorded at each follow-up visit. The Z-scores for weight-for-age and weight-for-height were calculated during each follow-up visit to assess changes in nutritional status. We also recorded events such as relapses, deaths, unscheduled extra-visits and re-hospitalisations. Any child developing pneumonia, diarrhoea or other complications requiring re-hospitalisation during the follow-up period was referred to the Dhaka Hospital of International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh/ICHSH for appropriate management. We also recorded the events related to hospitalisation of each child during the 3-month follow-up period. Other minor illnesses were treated by the study physician. Children who failed to attend the clinic/hospital on scheduled follow-up dates were visited in their homes by a healthcare worker next morning, who encouraged the parents to comply with follow-up visits and accompanied them back to the clinic/hospital on the same day for recording of all the above information by the study physician.

Data analysis including primary outcome measures

Success of day care/hospital care management at follow-up visits is defined as compliance with each of the scheduled follow-up visits for 3 months either spontaneously or brought by the healthcare workers, without the need for re-hospitalisation, or development of hypoxaemia and not dying during the whole follow-up period. However, the failure of day care/hospital care management at follow-up visits actually means re-hospitalisation, or development of hypoxaemia or death at any time during the 3 months of follow-up period. All data were collected on pre-designed case report forms, edited, entered onto a personal computer and analysed using statistical software, for example, Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS V.11.5; SPSS Inc), EPI Info V.6.0 and CIA. The primary outcome measures were expressed as the proportion of successes and failures of day care management at follow-up visits as determined by estimating ORs with their 95% CIs in comparison with hospital care results. The study groups were compared at the time of discharge from the clinic/hospital and during the follow-up period. The continuous variables were compared between the groups using Student t test and non-parametric tests. Dichotomous variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher' exact test, as appropriate. A probability of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

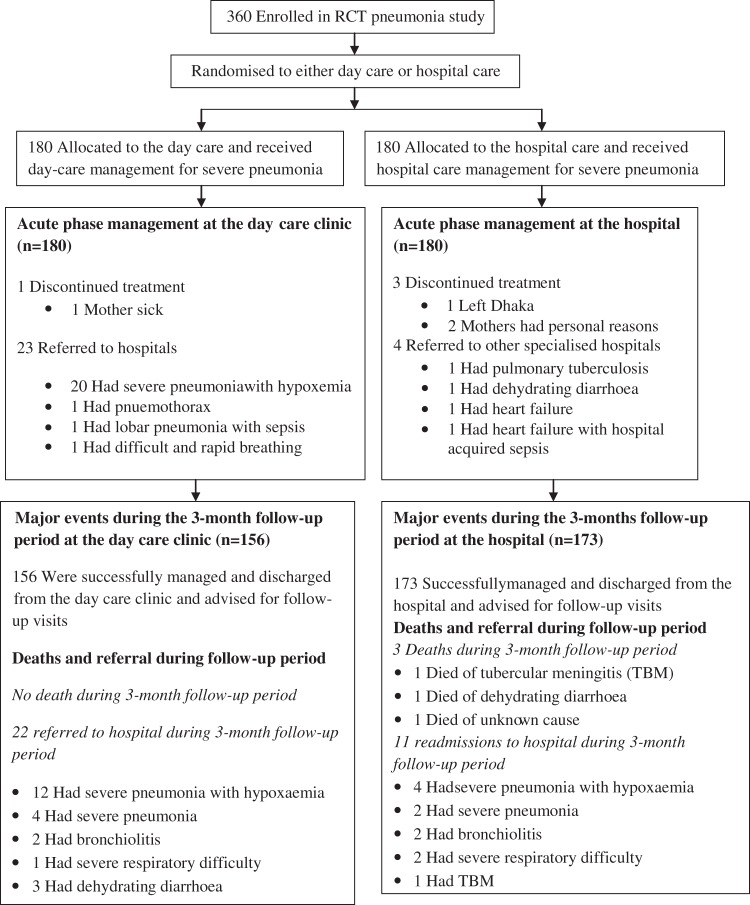

In total, 360 children living in the Mirpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh, with severe pneumonia were enrolled into the original randomised controlled trial study15 and were equally (180 in each) assigned randomly to the outpatient day care or inpatient hospital care (figure 1). The children were then followed up for 3 months after discharge from their primary treatment sites. The health status of the study children at the time of discharge from the clinic/hospital is shown in table 1. The mean age (SD) of the children was 8 (7) months, 291 (81%) were infants (2–11 months), 220 (61%) were men and 330 (92%) were breast fed with significantly more infants receiving the hospital care (table 1). Most of the children were well nourished without any wasting, but only with a mild degree of under-nutrition (table 1). About half of the children belonged to poor families (48%) with a monthly income of about US$70, while 72% of the fathers were day labourers or rickshaw-pullers, and 87% of the mothers were housewives.

Figure 1.

Trial profile of children with severe pneumonia. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 1.

Comparison of the ‘health’ status of the study children at the time of discharge

| Characteristics | Total (n=360) | Day care (n=180) | Hospital care (n=180) | p Value |

| Male, n (%) | 220 (61) | 102 (57) | 118 (66) | 0.08 |

| Age in month, mean (SD) | 8 (7) | 8.7 (8.0) | 7.3 (6.8) | 0.07 |

| Infants (2–11 months), n (%) | 291 (81) | 137 (76) | 154 (86) | 0.02 |

| 12–59 months, n (%) | 69 (19) | 43 (24) | 26 (14) | 0.02 |

| Breast fed, n (%) | 330 (92) | 163 (91) | 167 (93) | 0.44 |

| Weight on discharge, kg, mean (SD) | 6.59 (1.61) | 6.67 (1.67) | 6.52 (1.55) | 0.40 |

| Height on discharge, cm, mean (SD) | 64.97 (7.69) | 65.49 (8.28) | 64.45 (7.03) | 0.20 |

| Weight-for-age Z-score on discharge, mean (SD) | −1.47 (1.21) | −1.53 (1.21) | −1.41 (1.21) | 0.36 |

| Weight-for-height Z-score on discharge, mean (SD) | −0.82 (1.10) | −0.83 (1.09) | −0.82 (1.12) | 0.92 |

| Temperature, mean (SD) | 37.8 (0.8) | 37.7 (0.7) | 37.8 (0.7) | 0.08 |

| Pulse rate, beats per minute, mean (SD) | 130 (14) | 130 (15) | 130 (14) | 0.71 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths per minute, mean (SD) | 41 (9) | 42 (10) | 39 (8) | 0.007 |

| Difficulty in breathing, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Lower chest wall indrawing, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Hypoxaemia on discharge (oxygen saturation of <95%), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Oxygen saturation (%) on discharge, mean (SD) | 98 (1) | 98 (1) | 98 (1) | NA |

| Length of clinic/hospital stay (days), mean (SD) | 6.85 (2.61) | 7.13 (2.36) | 6.57 (2.81) | 0.04 |

| Median length of stay (days) | 6.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 | NA |

Compliance with follow-up visits after discharge from the clinic/hospital gradually reduced over time following discharge: 95%, 93%, 89%, 88%, 86% and 85% for the first, second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth visits, respectively (table 2). The common symptoms and signs noted during the follow-up visits included cough (28%), fever (17%), diarrhoea (9%) and rapid breathing (7%), while less common symptoms were chest indrawing (5%), feeding difficulties (5%) and difficulty in breathing (3%) (table 2). About 14% of the children reported minor illnesses such as poor appetite, otitis media, conjunctivitis, oral candidiasis (thrush), scabies and other skin infections, but 19% of the children required medication during the follow-up period (table 2). The sustainability of 3-month follow-up in the study group after discharge from the day care clinic is similar (≈90%) to that of the control group after discharge from the hospital (table 3). A significantly higher number of hospital care children reported cough, diarrhoea and feeding difficulty compared with day care children and needed more medication during the follow-up period (table 3). However, a significantly higher number of day care children reported respiratory problems such as rapid breathing and chest indrawing compared with hospital care children (table 3). Failure of both day care and hospital management were associated with the following: (1) the presence of tachycardia defined as pulse rate of more than 160 beats per minute; tachypnoea defined as respiratory rate of more than 60 breaths per minute and hypoxaemia with an oxygen saturation of <95% as recorded by pulse oximetry,17 18 all on admission and (2) prolonged duration of clinic/hospital stay for more than 10 days (table 4).

Table 2.

Compliance rates, morbidities and medications during each of the follow-up visits of study children

| 1st follow-up visit | 2nd follow-up visit | 3rd follow-up visit | 4th follow-up visit | 5th follow-up visit | 6th follow-up visit | Total | |

| Follow-up compliance | 342 (95) | 335 (93) | 322 (89) | 315 (88) | 311 (86) | 308 (85) | 1933 (89) |

| Cough | 94 (26) | 108 (30) | 95 (26) | 106 (29) | 105 (29) | 97 (27) | 605 (28) |

| Fever | 48 (13) | 60 (17) | 57 (16) | 72 (20) | 64 (18) | 64 (18) | 365 (17) |

| Rapid breathing | 20 (6) | 32 (9) | 22 (6) | 27 (7) | 30 (8) | 24 (7) | 155 (7) |

| Chest indrawing | 17 (5) | 25 (7) | 20 (6) | 17 (5) | 14 (4) | 14 (4) | 107 (5) |

| Feeding difficulty | 9 (2) | 24 (7) | 21 (6) | 18 (5) | 18 (5) | 8 (2) | 98 (5) |

| Difficult breathing | 16 (4) | 16 (4) | 8 (2) | 11 (3) | 5 (1) | 11 (3) | 67 (3) |

| Diarrhoea | 25 (7) | 41 (11) | 31 (9) | 34 (9) | 27 (7) | 35 (10) | 193 (9) |

| Minor illnesses | 54 (15) | 58 (16) | 40 (11) | 44 (12) | 58 (16) | 39 (11) | 293 (14) |

| Medicine taken | 58 (16) | 65 (18) | 71 (20) | 68 (19) | 76 (21) | 71 (20) | 409 (19) |

Values are n (%).

Table 3.

Comparison of compliance rates, morbidities and medications during the follow-up period

| Morbidity | Day care visits (n=1080) | Hospital care visits (1080) | Total follow-up visits (2160) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Compliance to all six follow-up visits | 976 (90) | 957 (89) | 1933 (89) | 1.21 (0.91 to 1.60) | 0.18 |

| Cough | 281 (46) | 324 (54) | 605 | 0.82 (0.68 to 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Fever | 177 (48) | 188 (52) | 365 | 0.93 (0.74 to 1.17) | 0.52 |

| Rapid breathing | 119 (77) | 36 (23) | 155 | 3.59 (2.41 to 5.37) | <0.001 |

| Chest indrawing | 74 (69) | 33 (31) | 107 | 2.33 (1.51 to 3.63) | <0.001 |

| Feeding difficulty | 31 (32) | 67 (68) | 98 | 0.45 (0.28 to 0.70) | <0.001 |

| Difficult breathing | 32 (48) | 35 (52) | 67 | 0.91 (0.55 to 1.52) | 0.70 |

| Diarrhoea | 78 (40) | 115 (60) | 193 | 0.65 (0.48 to 0.89) | 0.005 |

| Minor illnesses | 133 (45) | 160 (55) | 293 | 0.81 (0.63 to 1.04) | 0.08 |

| Medicine taken | 108 (26) | 301 (74) | 409 | 0.29 (0.22 to 0.37) | <0.001 |

Values are n (%).

Table 4.

Comparison of the study children in relation to their success and failure during the follow-up period

| Characteristic | Success (n=329) | Failure (n=31) | Total (n=360) | p Value |

| Male, n (%) | 202 (61) | 18 (58) | 220 (61) | 0.71 |

| Age months, mean (SD) | 7.88 (7.01) | 9.07 (11.33) | 7.98 (7.46) | 0.57 |

| Infants (2–11 months), n (%) | 264 (80) | 27 (87) | 291 (81) | 0.49 |

| Children (12–59 months), n (%) | 65 (20) | 4 (13) | 69 (19) | 0.49 |

| Breast fed, n (%) | 303 (92) | 27 (87) | 330 (92) | 0.25 |

| History of cough, n (%) | 328 (100) | 31 (100) | 359 (100) | 0.91 |

| History of fever, n (%) | 299 (91) | 29 (94) | 328 (91) | 0.46 |

| History of difficulty breathing, n (%) | 88 (27) | 7 (23) | 95 (26) | 0.61 |

| History of chest wall indrawing, n (%) | 117 (36) | 10 (32) | 127 (35) | 0.71 |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 6.51 (1.59) | 6.10 (1.89) | 6.48 (1.62) | 0.17 |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 64.69 (8.09) | 64.77 (10.24) | 64.69 (8.28) | 0.95 |

| Weight-for-age Z-score, mean (SD) | −1.37 (1.21) | −1.80 (0.85) | −1.41(1.19) | 0.06 |

| Weight-for-height Z-score, mean (SD) | −0.72 (2.48) | −1.07 (0.91) | −0.74 (2.39) | 0.45 |

| Temperature of >38°C, n (%) | 138 (42) | 14 (45) | 152 (42) | 0.72 |

| Pulse rate, beats per minute, mean (SD) | 152 (17) | 164 (16) | 153 (17) | 0.69 |

| Pulse rate of >160 beats per minute, n (%) | 82 (25) | 17 (55) | 99 (28) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths per minute, mean (SD) | 62 (10) | 67 (12) | 62 (10) | 0.007 |

| Respiratory rate >60 breaths per minute, n (%) | 170 (52) | 23 (74) | 193 (54) | 0.01 |

| Rales/crepitation on auscultation, n (%) | 325 (99) | 31 (100) | 356 (99) | 1.00 |

| Hepatomegaly (liver palpable for >2 cm), n (%) | 97 (29) | 9 (29) | 106 (29) | 0.95 |

| Duration of stay (day care/hospital), days, mean (SD) | 6.63 (2.10) | 9.19 (5.21) | 6.85 (2.61) | <0.001 |

| Duration of stay >10 days, n (%) | 17 (5) | 7 (23) | 24 (7) | <0.001 |

| Duration of antibiotic (Ceftriaxone) therapy, days, mean (SD) | 6.97 (1.59) | 7.84 (2.31) | 7.04 (1.67) | 0.006 |

| Hypoxaemia at admission (oxygen saturation <95%), n (%) | 164 (50) | 25 (81) | 189 (53) | 0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation at admission, mean (SD) | 94.92 (3.48) | 91.32 (5.54) | 94 (4) | <0.001 |

Successful follow-up visits for 3 months were possible in 146/180 (OR 81.1 (95% CI 74.8 to 86.2)) children who received day care, while it was possible in 162/180 (OR 90 (95% CI 84.7 to 93.6)) children who received hospital care (table 5). However, the remaining children failed to day care/hospital care management for re-hospitalisation, or development of hypoxaemia or death during the follow-up period (table 5). A significantly higher number of day care children (n=22 (OR 12.2 (95% CI 8.2 to 17.8))) required re-hospitalisation compared with hospital care children (n=11 (OR 6.1 (95% CI 3.4 to 10.6))) (OR 2.14, p=0.04) (table 5), as more day care children had hypoxaemia (n=12 (OR 6.7 (95% CI 3.9 to 11.3))) compared with the hospital care group (n=4 (OR 2.2 (95% CI 0.9 to 5.6))) (OR 3.14, p=0.04) (table 5). Similarly, a significantly higher number of children who presented with hypoxaemia during the acute phase of illness (n=25 (OR 13.2 (95% CI 9.1 to 18.8))) required re-hospitalisation during the follow-up period (OR 3.11, p=0.004) (data not shown here)15 compared with children who did not present with hypoxaemia during that phase of illness (n=8 (OR 4.7 (95% CI 2.4 to 9))). There were no deaths during the acute-phase care of children in either the day care or hospital care setting. During the follow-up period, no child in the day care group died but two (OR 1.1 (95% CI 0.3 to 4)) children in the hospital care group died and one (OR 0.6 (95% CI 0.1 to 3.1)) child died after the 3-month follow-up period.

Table 5.

Outcome for study children during the follow-up period

| Characteristic | Day care (n=180), n (OR (95% CI)) | Hospital care (n=180), n (OR (95% CI)) | Total (n=360), n (OR (95% CI)) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Successful follow-up visits | 146 (81.1% (74.8% to 86.2%)) | 162 (90% (84.7% to 93.6%)) | 308 (85.6% (81.5% to 88.8%)) | 0.48 (0.25 to 0.92) | 0.01 |

| Failure | 34 (18.9% (13.8% to 25.2%)) | 18 (10% (6.4% to 15.3%)) | 52 (14.4% (11.2% to 18.5%)) | 2.10 (1.09 to 4.05) | 0.01 |

| Re-hospitalisation during the follow-up period | 22 (12.2% (8.2% to 17.8%)) | 11 (6.1% (3.4% to 10.6%)) | 33 (9.2% (6.6% to 12.6%)) | 2.14 (0.95 to 4.88) | 0.04 |

| Development of hypoxaemia (oxygen saturation <95%) | 12 (6.7% (3.9% to 11.3%)) | 4 (2.2% (0.9% to 5.6%)) | 16 (4.4% (2.8% to 7.1%)) | 3.14 (0.92 to 11.80) | 0.04 |

| Death* | 0 (0% (0% to 2.1%)) | 3* (1.7% (0.6% to 4.8%)) | 3* (0.8% (0.3% to 2.4%)) | 0 | 0.12 |

Only one child died after 3-month follow-up period.

Discussion

In our study, we noted the great importance of follow-up after discharge from the clinic/hospital as some children relapsed or developed morbidities, and others needed unscheduled extra-clinic/hospital visits or re-hospitalisation, and a small number died during this period. Results from our study suggest the need to establish routine follow-up of children following successful management of severe pneumonia at healthcare facilities in order to detect medical problems early and to enable appropriate management and to prevent death. Such follow-up should be ideally done at the same healthcare facilities where the children had received their initial treatment, but a community follow-up system may be possible if trained and motivated community health workers and adequate resources are available.13 19

In our study, the follow-up compliance reduced over time. However, it was still impressive (85%) even at the end of 3 months (table 2)—a finding of considerable importance. Moreover, this impressive rate of follow-up was spontaneous—around 95% children were brought by their parents and the remaining 5% came after healthcare workers made home visits encouraging them to come. In general, incentives were not given but the study did support the conveyance costs of very poor families (4%) with a monthly income of about US$30 only. The finding that significantly more day care children suffered from rapid breathing and chest indrawing might be explained by the relatively more severe illness defined by hypoxaemia among them compared with the hospital care group. But, the hospital care group had significantly more feeding difficulty and diarrhoeal illness leading to consumption of more medications (table 3). The predictors for failure were the presence of tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypoxaemia on admission and prolonged duration of stay. Therefore, children presenting with tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypoxaemia on admission should be carefully monitored and aggressively treated, as they are unlikely to improve with routine therapy leading to prolonged stay. Similarly, the presence of tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypoxaemia on admission are also indicators for severe illness leading to failure of routine treatment.

Previous studies in Pakistan of community management of pneumonia by lady health worker with oral antibiotics10 and ambulatory home treatment with high-dose oral amoxicillin,11 without any necessity for referral to hospitals and without any injectable antibiotics, as well as without needing any oxygen therapy for hypoxaemia, have been reported. Our patient population probably had more severe disease judged by hypoxaemia, as 53% of our children were hypoxaemic on admission.15

There were some important limitations to our study. We could not assess the sustainability of a programme of 3-month follow-up visits at respective healthcare facilities where children had received their initial treatment. The feasibility as well as the sustainability of community follow-up should be assessed in future studies.

Conclusions

Successful follow-up visits for 3 months were possible in 81% of the day care children, while it was possible in 90% of the hospital care children. However, the remaining children failed to day care/hospital care management for re-hospitalisation, or development of hypoxaemia or death during the follow-up period. Children receiving apparently effective treatment of severe pneumonia experienced considerable morbidity due to cough, fever, rapid breathing and diarrhoea following discharge. The predictors for failure include the presence of tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypoxaemia on admission and prolonged duration of stay. These findings indicate the importance of follow-up of children with severe pneumonia irrespective of their primary site of management (day care clinic or hospital) for early detection and efficient management of subsequent medical problems and to reduce the risk of death. Establishment of an effective community follow-up of non-compliant children, whenever possible, would be ideal to address the problem of ‘non-compliance with follow-up’.

Trial registration

The original randomised controlled trial comparing the day care management with hospital management15 has been registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00455468).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support given by the Eagle Foundation (Geneva, Switzerland).

Footnotes

To cite: Ashraf H, Alam NH, Chisti MJ, et al. Observational follow-up study following two cohorts of children with severe pneumonia after discharge from day care clinic/hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000961. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000961

Contributors: HA, NHA and NG conceived the idea; HA, NHA and MAS contributed to study data interpretation; HA, MAS and NG wrote the paper. HA, NHA, MJC, MAS, TA and NG critically analysed and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Eagle Foundation (Geneva, Switzerland) (grant GR-00485).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Research and Ethical Review Committees of International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2010;375:1969–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudan I, Tomaskovic L, Boschi-Pinto C, et al. ; WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. Global estimate of the incidence of clinical pneumonia among children under five years of age. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:895–903. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rudan R, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, et al. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:408–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ashraf H, Chisti MJ, Alam NH. Treatment of childhood pneumonia in developing countries. In: Health Management, eds. Rijeka, Croatia: Sciyo, Krzysztof Smigorski ISBN 978-953-307-120-6 2010:59–88. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mulholland K. Magnitude of the problem of childhood pneumonia. Lancet 1999;354:590–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams BG, Gouws E, Boschi-Pinto C, et al. Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. Lancet Infect Dis 2002;2:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baqui AH, Black RE, Arifeen SE, et al. Causes of childhood deaths in Bangladesh: results of a nationwide verbal autopsy study. Bull World Health Organ 1998;76:161–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chisti MJ, Duke T, Robertson CF, et al. Co-morbidity: exploring the clinical overlap between pneumonia and diarrhoea in a hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Ann Trop Paediatr 2011;31:311–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. MASCOT pneumonia study group. Clinical efficacy of 3 days versus 5 days of oral amoxicillin for treatment of childhood pneumonia: a multicentre double-blind trial. Lancet 2002;360:835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bari A, Sadruddin S, Khan A, et al. Community case management of severe pneumonia with oral amoxicillin in children aged 2-59 months in Haripur district, Pakistan: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2011;378:1796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hazir T, Fox LM, Nasir YB, et al. ; For the New Outpatient Short-Course Home Oral Therapy for Severe Pneumonia (NO-SHOTS) Study Group. Ambulatory short-course high-dose amoxicillin for treatment of severe pneumonia in children: a randomised equivalency trial. Lancet 2008;371:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. Acute Respiratory Infections in Children: Case Management in Small Hospitals in Developing Countries. A Manual for Doctors and Other Senior Health Workers. WHO/ARI/90.5. Geneva: WHO, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ashraf H, Ahmed T, Hossain MI, et al. Day-care management of children with severe malnutrition in an urban health clinic in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J Trop Pediatr 2007;53:171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ashraf H, Jahan SA, Alam NH, et al. Day-care management of severe and very severe pneumonia, without associated co-morbidities such as severe malnutrition, in an urban health clinic in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:490–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ashraf H, Mahmud R, Alam NH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of day care versus hospital care of severe pneumonia in Bangladesh. Pediatrics 2010;126:e807–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ashraf H, Alam NH, Salam MA, et al. A follow-up experience of 6 months after treatment of children with severe acute malnutrition in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J Trop Pediatr. Published Online First: 11 October 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jubran A. Pulse oximetry. Crit Care 1999;3:R11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jubran A, Tobin MJ. Reliability of pulse oximetry in titrating supplemental oxygen therapy in ventilator-dependent patients. Chest 1990;97:1420–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khanum S, Ashworth A, Huttly SRA. Controlled trial of three approaches to the treatment of severe malnutrition. Lancet 1994;344:1728–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]