Abstract

Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I is an emerging zoonotic pathogen in humans. The lack of subtyping tools makes it impossible to determine the role of zoonotic transmission in epidemiology. To identify potential subtyping markers, we sequenced the genome of a human chipmunk genotype I isolate. Altogether, 9,509,783 bp of assembled sequences in 853 contigs were obtained, with an N50 of 117,886 bp and >200-fold coverage. Based on the whole-genome sequence data, two genetic markers encoding the 60-kDa glycoprotein (gp60) and a mucin protein (ortholog of cgd1_470) were selected for the development of a subtyping tool. The tool was used for characterizing chipmunk genotype I in 25 human specimens from four U.S. states and Sweden, one specimen each from an eastern gray squirrel, a chipmunk, and a deer mouse, and 4 water samples from New York. At the gp60 locus, although different subtypes were seen among the animals, water, and humans, the 15 subtypes identified differed mostly in the numbers of trinucleotide repeats (TCA, TCG, or TCT) in the serine repeat region, with only two single nucleotide polymorphisms in the nonrepeat region. Some geographic differences were found in the subtype distribution of chipmunk genotype I from humans. In contrast, only two subtypes were found at the mucin locus, which differed from each other in the numbers of a 30-bp minisatellite repeat. Thus, Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I isolates from humans and wildlife are genetically similar, and zoonotic transmission might play a potential role in human infections.

INTRODUCTION

Cryptosporidium is a common pathogen causing enteric diseases in humans and animals. The majority of human cases are caused by five species, including C. hominis, C. parvum, C. meleagridis, C. felis, and C. canis (1). However, 13 additional species as well as horse and skunk genotypes are occasionally found in humans (1, 2). Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I appears to be an emerging pathogen in humans. Although most Cryptosporidium spp. from wildlife are host adapted in nature and chipmunk genotype I was initially found in rodents (chipmunks, squirrels, and deer mice) and watershed runoff in New York (3, 4), it has been subsequently reported in sporadic cases in humans in the United States and Europe (5–8). The extent to which human infections with Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I are zoonotically transmitted is currently unclear, as there are no subtyping tools for tracking this emerging parasite.

The gene for a 60-kDa glycoprotein (gp60), a mucin, has been used extensively in subtyping C. parvum and C. hominis (2). The use of gp60-based subtyping tools has significantly improved our understanding of the importance of zoonotic transmission in the epidemiology of human C. parvum infections in different areas. Subtyping tools targeting the gp60 gene have been developed recently to characterize the transmission of other zoonotic Cryptosporidium species such as C. meleagridis and C. ubiquitum (9–11). In particular, host adaptation at the gp60 locus has been seen in C. ubiquitum, and there are geographic differences in the role of different animals in the transmission of C. ubiquitum infections in humans (9). Since Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I is genetically distant from C. parvum, C. hominis, C. meleagridis, and C. ubiquitum, gp60 primers are not yet available for subtyping this pathogen.

In this study, to develop a subtyping tool for the characterization of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I, we conducted whole-genome sequencing of one human isolate to identify the gp60 gene and nucleotide sequence encoding another mucin protein, the ortholog of cgd1_470 in C. parvum. Using these two genetic markers, we developed a subtyping tool to compare the genetic similarity among Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I isolates from humans, wildlife, and water.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

DNA extracts from 32 Cryptosporidium specimens were used in this study, including those from humans, wildlife, and storm runoff from a watershed (Table 1). These specimens were diagnosed as positive for Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I by DNA sequence analysis of an ∼830-bp fragment of the small subunit (SSU) RNA gene (12). They included 25 human specimens from sporadic cases in four U.S. states and Sweden (5–7), 3 wildlife specimens from one eastern gray squirrel, chipmunk, and deer mouse each in a watershed in New York (3), and 4 storm water samples from the same watershed (4).

TABLE 1.

Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I specimens used in the study and their subtype identities at the gp60 and mucin loci

| Host | Specimen | Source | gp60a | Mucin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 39969 | Maine | XIVaA16G2T2 | MCI |

| 37187 | Vermont | XIVaA17G2T3 | MCI | |

| 37189 | Vermont | XIVaA16G2T2 | MCI | |

| 37555 | Vermont | XIVaA16G2T2 | MCI | |

| 37763 | Vermont | XIVaA14G2T2 | MCI | |

| 37764 | Vermont | XIVaA15G2T3 | MCI | |

| 41602 | Vermont | XIVaA15G2T3 | MCI | |

| 41604 | Vermont | XIVaA16G2T2 | MCI | |

| 39974 | Wisconsin | XIVaA16G2T1 | —b | |

| 39975 | Wisconsin | XIVaA16G2T1 | MCI | |

| 40694 | Minnesota | XIVaA16G2T1 | MCII | |

| 40693 | Minnesota | XIVaA17G2T2 | MCII | |

| 40695 | Minnesota | XIVaA20G2T2 | MCII | |

| 40696 | Minnesota | XIVaA20G2T2 | MCII | |

| 40697 | Minnesota | XIVaA19G2T2a | MCII | |

| 40702 | Minnesota | XIVaA14G2T1 | MCII | |

| 40703 | Minnesota | XIVaA18G2T1b | MCI | |

| 40705 | Minnesota | XIVaA18G2T1b | MCII | |

| 40706 | Minnesota | — | MCII | |

| 40707 | Minnesota | — | MCII | |

| 40709 | Minnesota | XIVaA19G2T2b | MCII | |

| 39970 | Sweden | XIVaA20G2T1 | MCI | |

| 39971 | Sweden | XIVaA20G2T1 | MCI | |

| 39972 | Sweden | XIVaA20G2T1 | MCI | |

| 40136 | Sweden | XIVaA20G2T1 | MCI | |

| Eastern gray squirrel | 13469 | New York | XIVaA18G2T2 | MCII |

| Chipmunk | 12958 | New York | XIVaA18G2T1a | MCII |

| Deer mouse | 14985 | New York | XIVaA18G2T1a | MCI |

| Storm water | 8060 | New York | XVIa (skunk genotype?) | MCII |

| 8062 | New York | XIIb (C. ubiquitum) | MCII | |

| 6141 | New York | XIVaA15G2T1 | MCII | |

| 6143 | New York | XIIb (C. ubiquitum) | MCII |

Letters a and b following the trinucleotide repeat differentiate subtypes which have the same number of trinucleotide repeats but different trinucleotide repeat order.

—, no PCR amplification.

Whole-genome sequencing of chipmunk genotype I.

To identify subtyping markers for chipmunk genotype I, we sequenced the whole genome of one human isolate from Vermont. This specimen was chosen for whole-genome sequencing because of the high number of oocysts observed by microscopy. Oocysts were purified from the specimen by sucrose and cesium chloride density gradients and further purified by immunomagnetic separation. Genomic DNA was extracted from the purified oocysts by a QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen Sciences, MD, USA) and amplified using a REPLI-g Midi kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) before whole-genome sequencing using the Illumina TruSeq (v3) library protocol on an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Because of the premature termination of the sequencing run, only single-end 100-bp reads were available for sequence assembly, which was done using the CLC Genomics Workbench (CLC Bio, Boston, MA). The contigs generated were mapped to published whole-genome sequences of C. parvum using Mauve (http://asap.genetics.wisc.edu/software/mauve/) to identify orthologs of the gp60 (cgd6_1080) and mucin cgd1_470 genes.

PCR analysis of gp60 and cgd1_470 mucin genes.

Based on conserved sequences between chipmunk genotype I and C. parvum, nested PCR primers were designed to flank the entire coding region of the gp60 gene and part of the mucin cgd1_470 gene, with the expected secondary PCR products of 1,072 bp and 966 bp, respectively (Table 2). The total volume of both the primary and secondary PCR mixture was 50 μl, which contained 1 μl of DNA (for primary PCR) or 2 μl of the primary PCR product, 250 nM primary primers or 500 nM secondary primers, 3 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 1× GeneAmp PCR buffer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and 1.5 U of Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI). The amplification was performed on a GeneAmp PCR 9700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems), consisting of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min; 35 cycles at 94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. To reduce PCR inhibitors, 400 ng/μl of nonacetylated bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used in the primary PCR. The secondary PCR products were visualized under UV light after 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide sequences in the primer regions of PCR targeting the Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I and their corresponding sequences in Cryptosporidium ubiquitum

| Species/genotype | Locus | Nucleotide sequence in the primer region |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | R1 | F2 | R2 | ||

| Chipmunk genotype I | gp60 | TTTACCCACACATCTGTAACGTCG | CCTGTGAGAATATTCTGGAAATTA | ATAGGTAATAATTACTCAGTATTTAAT | TACTCTTAAAACGCTTAAACTCTTAA |

| C. ubiquitum | gp60 | TTTACCCACACATCTGTAGCGTCG | CCTGTGAGAATATTCTGGAAATTA | ATAGGTAATAATTAGTCAGTCTTTAAT | TACTTTTTAAAGCGCTTAAACTCTTAA |

| Chipmunk genotype I | Mucin | GTCAGGATCATCTTCAACTAAAAC | GGAACTGATGACATCTCTACA | TTCTAGAGTCGGGTCATCTACA | TCGGGAGATATTCCGTATCTC |

| C. ubiquitum | Mucin | GTCAGGATCATCTTCAACTAAAAC | AGATTTAATGAGTTCTTTACA | AGGAACAACAAGGCCATCAGGAACA | TCGGGTTATTGCTTTGTCTCT |

Sequence analysis.

The secondary gp60 PCR products were sequenced using the secondary reverse primer R2 and an intermediary sequence primer R3 (5′-ACC AGA GAT ATA TCT CGG TGC-3′),while the secondary mucin PCR products were sequenced using the secondary forward and reverse primers. The sequencing of all PCR products was performed using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences from each PCR product were assembled by ChromasPro 1.32 (Technelysium), edited in BioEdit 7.04 (www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html), and aligned with reference sequences using ClustalX 2.1 (www.clustal.org/). To assess the genetic relatedness of chipmunk genotype I to the major Cryptosporidium subtype families, neighbor-joining trees were constructed using the program TREECONW (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/software/details/Treecon), based on the evolutionary distance calculated by the Kimura two-parameter model. In addition, the amino acid sequence of the gp60 gene of the chipmunk genotype I was aligned with sequences of C. parvum, C. hominis, and C. ubiquitum using ClustalX 2.1. The structure and N- and O-glycosylated sites were predicted using the PSORT II (http://psort.hgc.jp/form2.html), NetNGlyc 1.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetNGlyc/), and YinOYang 1.2 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/YinOYang/) servers, respectively. A potential furin cleavage site in the sequence was predicted with the ProP 1.0 server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ProP/).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The whole-genome sequence data of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I were submitted to NCBI genome data under accession number SAMN03281121. Nucleotide sequences of the gp60 and mucin cgd1_470 genes generated in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KP099078 to KP099097.

RESULTS

Whole-genome sequence data.

The assembly of Illumina sequence reads consisted of 9,509,783 bp in 853 contigs, with an estimated 227-fold coverage and an N50 of 117,886 bp. Altogether, 9,009,492 bp in 150 contigs were mapped to the reference C. parvum genome, giving a 98.98% coverage of its genome. The remaining contigs were mostly small and from the C. hominis IbA10G2 subtype, likely the result of mixed infections. One contig (478,353 bp) contained the ortholog of cgd6_1080, which had a high sequence similarity at the 5′ and 3′ ends to the gp60 gene of C. parvum. Another contig (117,886 bp) covered the mucin protein cgd1_470 gene of C. parvum, with high sequence homology in the second half of the gene. A comparative genomic analysis of the genome will be performed after the annotation of the whole-genome sequences.

Characteristics of gp60 gene of chipmunk genotype I.

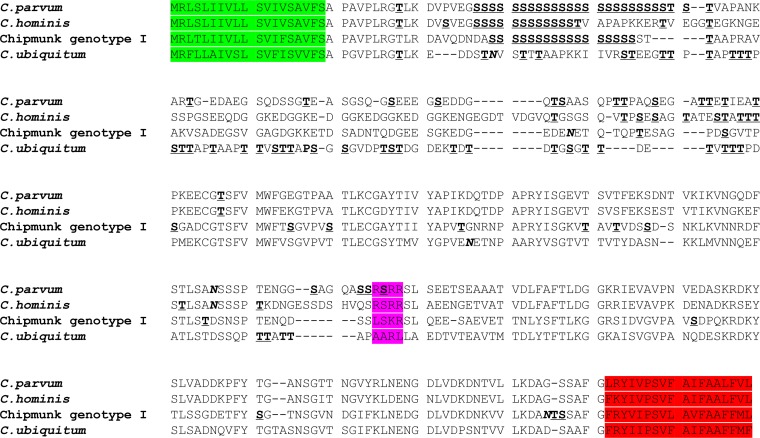

The gp60 gene retrieved from the whole-genome sequencing data of specimen 37763 consisted of 963 nucleotides and coded for a peptide of 320 amino acids. Except for the 5′ and 3′ regions, the nucleotide sequence of chipmunk genotype I was significantly different from those of C. parvum, C. hominis, C. ubiquitum, and related species; the amino acid sequences of C. parvum, C. hominis, C. ubiquitum and chipmunk genotype I shared only 45% to 54% identity (Fig. 1). The structure of the gp60 gene was nevertheless similar to the one in C. parvum and C. hominis. The first 19 hydrophobic and hydroxylic amino acids constituted an N-terminal signal peptide with a signal peptide cleavage site between amino acids Ser19 and Ala20, and the last 19 amino acids coded for a transmembrane domain. As in C. parvum, C. hominis, and C. ubiquitum, the hydrophobic C-terminal sequence of the gp60 protein in chipmunk genotype I was likely linked to a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor (9, 13, 14). Following the signal peptide, the deduced protein sequence contained a polyserine track comprising 18 Ser residues, of which the first 17 were all predicted to be O-glycosylated. There were several other Ser and Thr residues throughout the sequence that were predicted to be O-glycosylated. In addition, two potential N-glycosylated sites were identified in contrast to one N-glycosylated site in C. parvum and C. hominis. The conserved amino acid sequence RSRR for the furin cleavage site, which is seen at the end of gp40 region of the gene of most C. parvum and C. hominis subtype families (15), was replaced by the sequence LSKR in chipmunk genotype I.

FIG 1.

Deduced amino acid sequence of the gp60 gene of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I compared with sequences of C. parvum (GenBank accession no. AF022929, C. hominis (GenBank accession no. ACQ82748), and C. ubiquitum (9). Potential N-glycosylation sites are indicated in boldface and italic type, and predicted O-glycosylation sites are indicated in boldface and underlined type. The first 19 amino acids coding for a signal peptide are highlighted in green, and the last 17 amino acids for a transmembrane domain are highlighted in red. The classic furin cleavage site sequence RSRR in the C terminus of gp40 is highlighted in purple. Dashes denote amino acid deletions.

PCR amplification of gp60 and mucin protein genes of chipmunk genotype I.

With primers designed in this study, the nested PCR yielded the expected products for 30 and 31 of the 32 DNA extracts analyzed at the gp60 and mucin loci, respectively (Table 1). All gp60 PCR products were sequenced successfully using R2 and R3 primers, although the use of F2 in sequencing produced mostly noisy sequences because of the presence of a poly(A) track (13 consecutive nucleotide A) shortly after the primer sequence. Except for three water samples, which were originally shown to have mixed Cryptosporidium genotypes (4), the gp60 sequences generated were homologous to the chipmunk genotype I sequence from the whole-genome sequencing. They differed mostly in the number of trinucleotide repeats. Two of the three remaining gp60 sequences from the water sample lacked the trinucleotide repeats, had numerous nucleotide substitutions (single nucleotide polymorphism [SNP]) compared to the reference and were 99% identical to GenBank sequence JX412926 from the gp60 gene of the C. ubiquitum XIIb subtype family. The third sequence had trinucleotide repeats and 79% sequence identity to the gp60 gene of a C. fayeri isolate (GenBank sequence FJ490070) with the maximum query coverage (72%) among the GenBank sequences. In contrast, at the mucin locus, all sequences generated were homologous to the reference sequence from the whole-genome sequencing.

Subtypes of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I.

At the gp60 locus, 15 subtypes of chipmunk genotype I were found in the 27 sequences that had high homology to the chipmunk genotype I reference sequence (Table 1). They differed from each other mostly in the number of trinucleotide repeats (TCA, TCG, or TCT) in the serine repeat region, with only two SNPs in the nonrepeat region. The subtype family consisting of these 15 subtypes was named XIVa in concordance with the established nomenclature of gp60 subtype families (2, 9). The biggest difference in length within this subtype family was 21 bp. Twelve of the 15 subtypes were found in 23 human specimens (Table 1). Unique subtypes were generally seen in different geographic regions. However, humans in neighboring states were sometimes infected with identical subtypes. Thus, four specimens from Maine and Vermont belonged to the subtype XIVaA16G2T2, whereas three specimens from Wisconsin and Minnesota belonged to the subtype XIVaA16G2T1. As expected, multiple subtypes were seen in humans in Minnesota and Vermont, where more specimens were available for analysis. However, all four human specimens in Sweden collected over a 6-year period had the same subtype (XIVaA20G2T1). Two subtypes were found among the three wildlife specimens from New York, and both were different from those in humans elsewhere (Table 1). The only storm water sample that produced a Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I sequence also had a different subtype.

At the mucin locus, two subtypes were seen: MCI and MCII. They differed from each other only in the number of a 30-bp minisatellite repeat. These two subtypes were present in all types of specimens and all geographic regions (Table 1).

Genetic relationship among gp60 subtypes of chipmunk genotype I.

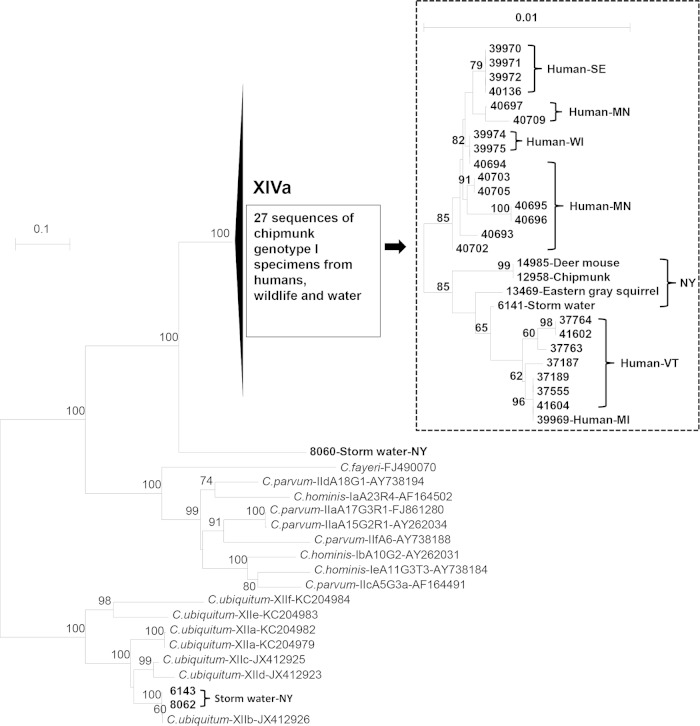

A neighbor-joining tree was constructed with the gp60 sequences from the study and some major subtype families of Cryptosporidium spp. In this tree, all 27 gp60 sequences of chipmunk genotype I clustered into one major group, the sequence from storm water sample 8060 with only 72% sequence identity to the reference of chipmunk genotype I formed a separate branch, and the sequences from storm water samples 6143 and 8062 clustered within the XIIb subtype family of C. ubiquitum (Fig. 2). Within the Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I group (the XIVa subtype family), two geographical clusters were seen. Specimens from New York, Maine, and Vermont, the three Northeast U.S. states, clustered together, whereas specimens from Minnesota and Wisconsin, the two Midwest states, and Sweden formed another cluster (Fig. 2, inset).

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic relationship among the subtypes of C. parvum, C. hominis, C. ubiquitum, and chipmunk genotype I by a neighbor-joining analysis of the gp60 gene using distances calculated by the Kimura two-parameter model. Numbers on branches are percent bootstrapping values (>50) using 1,000 replicates.

DISCUSSION

In this study, two genetic markers for subtyping Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I from whole-genome sequence data generated by Illumina sequencing, including the gp60 and cgd1_470 mucin genes, were identified. Both genes have nucleotide sequences that are substantially different from those of C. parvum and C. hominis, which explains the inability of regular PCR primers to amplify DNA of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I. Nevertheless, both genes maintain some of the characteristics typical of mucin genes, coding for proteins rich in serine with heavy O-linked glycosylation. Like in other Cryptosporidium species such as C. parvum, C. hominis, and C. ubiquitum, the gp60 gene of chipmunk genotype I also has a signal peptide, a transmembrane domain, and a GPI anchor. However, it is not yet clear whether the gp60 protein of chipmunk genotype I has a furin cleavage site. The classic furin cleavage sequence RSRR is not present at the gp40 end of the protein. Nevertheless, it has an LSKR sequence at the same location, a sequence very similar to the ISKR sequence in the C. hominis Ie subtype family, which is also cleaved by furin (15). In contrast, the gp60 protein of C. ubiquitum apparently lacks the furin cleavage site (9). In C. parvum and C. hominis, the gp60 precursor protein is processed at the furin cleavage site into gp40 and gp15, possibly by a subtilisin-like serine protease (cgd6_4840) (16). As the process plays a key role in the invasion of sporozoites (15), the difference in the proteolytic cleavage of gp60 may potentially be responsible for some biologic differences among Cryptosporidium species.

As expected, the gp60 gene of chipmunk genotype I is highly polymorphic, generating 15 subtypes among the 30 isolates analyzed from humans, wildlife, and storm water. Nevertheless, subtypes differ only in the number of tandem repeats (TCA/TCG/TCT) and comprise a single subtype family. In contrast, the gp60 gene in most other Cryptosporidium species characterized, including C. parvum, C. hominis, C. meleagridis, C. cuniculus, C. tyzzeri, C. fayeri, and C. ubiquitum, has multiple subtype families that differ substantially in the sequence of the nonrepeat regions (9, 11, 14, 17–19). Previously, host adaptation has been seen among subtype families within C. parvum, C. tyzzeri, and C. ubiquitum (2, 9, 20). Whether there is an absence of host adaptation within the Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I remains to be determined, as the number of animal specimens characterized is small, and the animal subtypes identified did not match those found in humans elsewhere. Nevertheless, the genetic similarity of human and animal isolates shown in this study clearly indicates that zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I is possible.

There were some geographic differences in the distribution of gp60 subtypes in the present study. The neighboring states of Maine and Vermont and of Minnesota and Wisconsin had common subtypes. In the neighbor-joining analysis of nucleotide sequences, subtypes from the northeast U.S. states of New York, Vermont, and Maine clustered into one major group, while the remaining subtypes from Midwest states and Sweden formed a second group. The segregation of the two groups is mainly due to the presence of one nucleotide substitution in the nonrepeat region of the gene. In addition, the genetic diversity of chipmunk genotype I in Minnesota and Vermont appears to be higher than that in Sweden; all four specimens from the latter had the same subtype that was not seen in other areas. The reason for the reduced subtype diversity of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I in Sweden is not clear. Europe has no chipmunks or deer mice and only one native squirrel species, the red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris), which has been identified as a host for Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I (21). This reduced host diversity might be partially responsible for the limited subtype diversity of the Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I in Sweden.

The gp60 PCR primers designed in this study appear to have broad specificity as some PCR products amplified from water samples are from other Cryptosporidium spp. Two samples that were previously diagnosed as having chipmunk genotype I and C. ubiquitum by DNA sequence analysis of the SSU RNA gene generated only gp60 sequences of the C. ubiquitum XIIb subtype family. This is not surprising, as the primer sequences in the study were chosen from intergenic regions flanking the gp60 gene that were conserved in C. parvum, C. hominis, C. ubiquitum, and chipmunk genotype I. As C. ubiquitum has nucleotide sequences very similar to those of the chipmunk genotype I in the primer regions (Table 2), the PCR apparently amplified only the C. ubiquitum sequence in the two samples with mixed C. ubiquitum and chipmunk genotype I populations. The PCR primers can apparently also amplify the gp60 gene of another unknown Cryptosporidium sp., as a new subtype family which was related to XIVa and named XVIa was amplified from water sample 8060. Because the sample had a concurrent Cryptosporidium skunk genotype (W13) based on the analysis of the SSU RNA gene, this new gp60 subtype sequence might be from this parasite. Thus, only one of the four water samples analyzed in the study produced the gp60 gene sequence (XIVa subtype family) of the Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I.

The mucin protein gene cgd1_470 of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I has a much lower sequence polymorphism than the gp60 gene. The two subtypes, MCI and MCII, found at the mucin protein locus differ from each other only in the number of a 30-bp minisatellite repeat. In wildlife, MCI was found in a deer mouse, and MCII was found in an eastern gray squirrel and a chipmunk. However, all storm water samples belong to MCII. In human specimens, except for specimens from Minnesota where MCII was the dominant subtype, specimens from other regions all belonged to MCI. The finding of the same mucin protein subtype in humans and animals also supports the zoonotic potential of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I.

In conclusion, a subtyping tool based on two markers for genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I has been developed. The application of this new tool thus far suggests that Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I isolates from humans and wildlife are genetically similar; therefore, zoonotic transmission might play a potential role in the epidemiology of human infections with this emerging pathogen. Further studies are needed to confirm the geographic difference in the distribution of subtypes and delineate the role of various wildlife and drinking water in human infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31229005, 31110103901, and 31425025), the Water Special Project (2014ZX07104006), the National Special Fund for State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering (no. 2060204), and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ryan U, Fayer R, Xiao L. 2014. Cryptosporidium species in humans and animals: current understanding and research needs. Parasitology 141:1667–1685. doi: 10.1017/S0031182014001085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao L. 2010. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol 124:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng Y, Alderisio KA, Yang W, Blancero LA, Kuhne WG, Nadareski CA, Reid M, Xiao L. 2007. Cryptosporidium genotypes in wildlife from a new york watershed. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:6475–6483. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang J, Alderisio KA, Xiao L. 2005. Distribution of Cryptosporidium genotypes in storm event water samples from three watersheds in New York. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4446–4454. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4446-4454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feltus DC, Giddings CW, Schneck BL, Monson T, Warshauer D, McEvoy JM. 2006. Evidence supporting zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. in Wisconsin. J Clin Microbiol 44:4303–4308. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01067-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Insulander M, Silverlas C, Lebbad M, Karlsson L, Mattsson JG, Svenungsson B. 2013. Molecular epidemiology and clinical manifestations of human cryptosporidiosis in Sweden. Epidemiol Infect 141:1009–1020. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812001665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebbad M, Beser J, Insulander M, Karlsson L, Mattsson JG, Svenungsson B, Axen C. 2013. Unusual cryptosporidiosis cases in Swedish patients: extended molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium viatorum and Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I. Parasitology 140:1735–1740. doi: 10.1017/S003118201300084X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ANOFEL Cryptosporidium National Network. 2010. Laboratory-based surveillance for Cryptosporidium in France, 2006-2009. Euro Surveill 15:pii=19642 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li N, Xiao LH, Alderisio K, Elwin K, Cebelinski E, Chalmers R, Santin M, Fayer R, Kvac M, Ryan U, Sak B, Stanko M, Guo YQ, Wang L, Zhang LX, Cai JZ, Roellig D, Feng YY. 2014. Subtyping Cryptosporidium ubiquitum, a zoonotic pathogen emerging in humans. Emerg Infect Dis 20:217–224. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.121797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stensvold CR, Beser J, Axen C, Lebbad M. 2014. High applicability of a novel method for gp60-based subtyping of Cryptosporidium meleagridis. J Clin Microbiol 52:2311–2319. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00598-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baroudi D, Khelef D, Goucem R, Adjou KT, Adamu H, Zhang H, Xiao L. 2013. Common occurrence of zoonotic pathogen Cryptosporidium meleagridis in broiler chickens and turkeys in Algeria. Vet Parasitol 196:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao L, Sulaiman IM, Ryan UM, Zhou L, Atwill ER, Tischler ML, Zhang X, Fayer R, Lal AA. 2002. Host adaptation and host-parasite co-evolution in Cryptosporidium: implications for taxonomy and public health. Int J Parasitol 32:1773–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cevallos AM, Zhang X, Waldor MK, Jaison S, Zhou X, Tzipori S, Neutra MR, Ward HD. 2000. Molecular cloning and expression of a gene encoding Cryptosporidium parvum glycoproteins gp40 and gp15. Infect Immun 68:4108–4116. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.7.4108-4116.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strong WB, Gut J, Nelson RG. 2000. Cloning and sequence analysis of a highly polymorphic Cryptosporidium parvum gene encoding a 60-kilodalton glycoprotein and characterization of its 15- and 45-kilodalton zoite surface antigen products. Infect Immun 68:4117–4134. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.7.4117-4134.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanyiri JW, O'Connor R, Allison G, Kim K, Kane A, Qiu J, Plaut AG, Ward HD. 2007. Proteolytic processing of the Cryptosporidium glycoprotein gp40/15 by human furin and by a parasite-derived furin-like protease activity. Infect Immun 75:184–192. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00944-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanyiri JW, Techasintana P, O'Connor RM, Blackman MJ, Kim K, Ward HD. 2009. Role of CpSUB1, a subtilisin-like protease, in Cryptosporidium parvum infection in vitro. Eukaryot Cell 8:470–477. doi: 10.1128/EC.00306-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Power ML, Cheung-Kwok-Sang C, Slade M, Williamson S. 2009. Cryptosporidium fayeri: Diversity within the GP60 locus of isolates from different marsupial hosts. Exp Parasitol 121:219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng Y, Lal AA, Li N, Xiao L. 2011. Subtypes of Cryptosporidium spp. in mice and other small mammals. Exp Parasitol 127:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalmers RM, Robinson G, Elwin K, Hadfield SJ, Xiao L, Ryan U, Modha D, Mallaghan C. 2009. Cryptosporidium sp. rabbit genotype, a newly identified human pathogen. Emerg Infect Dis 15:829–830. doi: 10.3201/eid1505.081419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kváč M, McEvoy J, Loudova M, Stenger B, Sak B, Kvetonova D, Ditrich O, Raskova V, Moriarty E, Rost M, Macholan M, Pialek J. 2013. Coevolution of Cryptosporidium tyzzeri and the house mouse (Mus musculus). Int J Parasitol 43:805–817. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kvac M, Hofmannova L, Bertolino S, Wauters L, Tosi G, Modry D. 2008. Natural infection with two genotypes of Cryptosporidium in red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) in Italy. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 55:95–99. doi: 10.14411/fp.2008.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]