Abstract

Porcine epidemic diarrhea has become pandemic in the Asian pig-breeding industry, causing significant economic loss. In the present study, 11 complete genomes of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) field isolates from China were determined and analyzed. Frequently occurring mutations were observed, which suggested that full understanding of the genomic and epidemiological characteristics is critical in the fight against PEDV epidemics. Comparative analysis of 49 available genomes clustered the PEDV strains into pandemic (PX) and classical (CX) groups and identified four hypervariable regions (V1 to V4). Further study indicated key roles for the spike (S) gene and the V2 region in distinguishing between the PX and CX groups and for studying genetic evolution. Genotyping and phylogeny-based geographical dissection based on 219 S genes revealed the complexity and severity of PEDV epidemics in Asia. Many subgroups have formed, with a wide array of mutations in different countries, leading to the outbreak of PEDV in Asia. Spatiotemporal reconstruction based on the analysis suggested that the pandemic group strains originated from South Korea and then extended into Japan, Thailand, and China. However, the novel pandemic strains in South Korea that appeared after 2013 may have originated from a Chinese variant. Thus, the serious PED epidemics in China and South Korea in recent years were caused by the complex subgroups of PEDV. The data in this study have important implications for understanding the ongoing PEDV outbreaks in Asia and will guide future efforts to effectively prevent and control PEDV.

INTRODUCTION

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) is an acute enteric tract infectious disease characterized by thin-walled intestines with severe villus atrophy and congestion, which can rapidly lead to death from acute watery diarrhea and vomit, especially in piglets (1–3). Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), the etiological agent (4, 5), is an alphacoronavirus from the family Coronaviridae of the order Nidovirales (6).

The PEDV genome is approximately 28 kb in length and comprises seven open reading frames (ORFs) (7, 8). The spike (S) gene of PEDV encodes the spike glycoprotein and can be divided into S1 and S2 domains, just as in other coronaviruses (9–11). The S glycoprotein interacts with the cellular receptor to regulate viral entry and contains neutralizing epitopes to induce neutralizing antibodies (12, 13). In addition, the S gene shows a high degree of genetic diversity (14), especially in the S1 domain or the N-terminal region of the S1 domain (15–17), and is considered an important gene marker in understanding genetic variations of PEDV strains in the field (16, 18, 19).

The first PEDV strain, CV777, was recognized in Belgium in 1977 (4, 5). Postemergence, several European nations reported disease outbreaks (20, 21). Currently, PED disease is causing serious losses in the pig industry in many Asian nations, including South Korea (14, 22, 23), Thailand (9, 18), and China (24). At present, strains of PEDV cause more severe clinical symptoms than previous strains; pigs of all ages are affected and exhibit different degrees of diarrhea and loss of appetite (2, 18, 23). The strains emerging in Asia are distinct from previous endemic PEDV strains and may have been introduced from overseas (9, 23).

In the present study, 11 complete genomic sequences of Chinese field strains collected from 2011 to 2014 were determined. Together with 38 other available PEDV genomes, they were used to analyze genome characteristics and evaluate the genetic stability of the virus. Furthermore, we analyzed the epidemic regularity of 219 PEDV field strains, determined the relationship among PEDV strains more precisely, and revealed the phylogeography and spatiotemporal spread of PEDV in Asia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and treatment.

From April 2011 to March 2014, nine intestinal homogenates and two feces samples were collected from pigs that had severe diarrhea and a high mortality rate at 11 farms (Table 1). PEDV infection was confirmed by a PEDV membrane (M) gene-based reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (25) and by sequencing. The 11 positive PEDV samples were from large-scale commercial swine farms (>50,000 pigs) and were inoculated with PEDV vaccine. In each outbreak, intestinal or feces samples collected from 3- to 4-day-old piglets displayed the clinical features associated with PED, including watery diarrhea, loss of appetite, vomiting, and dehydration.

TABLE 1.

Eleven PEDV isolates obtained from different farms in China during outbreaks in 2011 to 2014

| Strain name | Sample origin | GenBank accession no. | Nations | Collection date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEDV-1C | Small intestine | KM609203 | China | March 2012 |

| PEDV-7C | Small intestine | KM609204 | China: JiangXi | June 2011 |

| PEDV-8C | Small intestine | KM609205 | China | Unknown |

| PEDV-10F | Feces | KM609206 | China: JiangSu | January 2012 |

| PEDV-14 | Small intestine | KM609207 | China: ZheJiang | April 2011 |

| PEDV-15F | Feces | KM609208 | China: ChongQing | March 2012 |

| PEDV-CHZ | Small intestine | KM609209 | China: JiangSu | March 2013 |

| PEDV-LY | Small intestine | KM609210 | China: ShanDong | January 2014 |

| PEDV-LS | Small intestine | KM609211 | China: ShanDong | January 2014 |

| PEDV-LYG | Small intestine | KM609212 | China: JiangSu | March 2014 |

| PEDV-WS | Small intestine | KM609213 | China: ZheJiang | March 2014 |

These samples were collected individually and placed in separate sterile specimen containers. The minced intestinal and blended feces were used to generate a 10% (g/ml) homogenate in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The homogenate was freeze-thawed three times, vortexed, and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The final supernatants were used immediately or stored at −20°C.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

The primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were designed based on the highly conserved sites of the PEDV reference strain CHGD-01 (GenBank accession no. JX261936.1), using Oligo 6.0. Six overlapping DNA fragments were amplified by RT-PCR.

Viral RNA extraction, RT-PCR amplification, and cloning were performed according to conventional protocols, with some modifications (26). In brief, viral RNA was extracted from the supernatants of the homogenized positive samples using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Viral RNA was eluted into 50 μl of RNase-free water. HiScript reverse transcriptase (HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA synthesis kit; Vazyme, China) was used to synthesize cDNA from the extracted RNA and stored at −20°C. The amplifications for the six overlapping DNA fragments were performed using LAmp DNA polymerase (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). A SMARTer rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) kit (Clontech, Japan) confirmed the 5′ and 3′ ends of the genome, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Whole-genome sequence and assembly.

In brief, bands of corresponding size of the RT-PCR products were excised, and a QIAquick gel extraction kit (TaKaRa, Shanghai, China) was used to purify the synthesized DNA, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Shanghai Sunny Biotechnology Co, Ltd. (Shanghai, China) sequenced the purified products. Each nucleotide was identified from the replicates that gave identical results. The DNAStar software package (DNAStar Inc., Madison, WI, USA) was used to assemble and analyze the sequencing data. The complete genome sequences of the 11 Chinese PEDV strains were submitted to the GenBank database with the accession numbers shown in Table 1.

Variation analysis of 49 whole PEDV genomes.

The method of calculating the variation coefficient is shown in Fig. S1A in the supplemental material. One hundred base pairs at a time were extracted from the alignment of 49 whole PEDV genomes (Table 1; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material) constructed by MEGA (v5.0.3) software (27), which contained a total of 4,900 points, and analyzed. If the nucleotide at one point was dissimilar to the common one, it was defined as a variable point. The variation coefficient was the number of variable points in every 100 bp, and the maximum value was 2,400. The analysis was repeated by sliding the analysis window forward by 20 bp and analyzing the next 100 bp. A total of 1,404 variation coefficients were calculated by our procedure (http://www.chinasscontrol.com/biosystem/index.php). A vertical value of >100 was consider a dissimilar region. Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to construct a graph of the variation coefficients with a window size of 100 bp and a step of 20 bp.

Multiple-sequencing alignments and phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis was performed following the procedures outlined by Chen et al. (15). ClustalW alignments with default parameters were produced for the whole genome, the entire spike gene, the N-terminal domain (NTD) of the S gene (corresponding to nucleotides [nt] 20635 to 21813 [covering 1,179 bp] of the strain AH2012), and the four most variable regions (V1 to V4; Fig. 1A). Phylogenetic trees were constructed separately with the molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software package (v.5.0.3) (27) using the neighbor-joining method, with p-distance, complete gap deletion, and bootstrapping (n = 1,000) parameters.

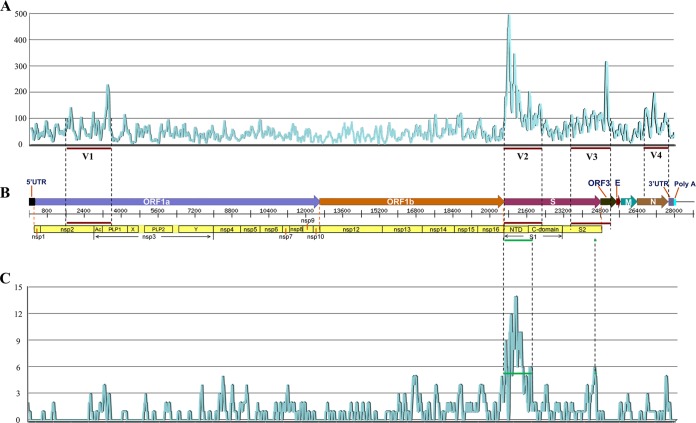

FIG 1.

(A) Variation analysis of 49 whole PEDV genomes from NCBI. The graph shows the variation coefficient (window size = 100 bp, step = 20 bp) in the alignment of 49 whole PEDV genomes. The detailed calculation method of the variation coefficient is shown in Fig. S1A in the supplemental material. Dashed and thick red lines, positions of four high mutation regions (V1, V2, V3, and V4) containing more nucleic acid deletions/insertions/mutations. (B) Organization of the PEDV genome. The approximate positions and sizes of genes in the PEDV genome correspond to the scale bar. The putative S1-S2 boundary (amino acid positions) of the S protein is also shown. (C) Analysis of nucleotide positions distinguishing classical and pandemic pathotypes (DCP). Graph showing the DCP position content (window size = 100 bp, step = 20 bp) in the alignment of 49 whole PEDV genomes. The detailed calculation method of DCP position is shown in Fig. S1B in the supplemental material. Dashed and green thick line, the major regions containing abundant DCP positions.

Analysis of nucleotide positions distinguishing PEDV classical and pandemic groups (DCP).

The calculation method for the DCP values is shown in Fig. S1B in the supplemental material. Some DCP nucleotide positions are indicated by blue boxes as typical examples. The number of DCP positions defined the DCP value, which was calculated with a window size of 100 bp and a step of 20 bp. The baseline of the value was 6. Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used to draw the graph of the DCP values (window size of 100 bp, step of 20 bp).

Antigenic index and hydrophilicity plots.

Four strains were subjected to antigenic index and hydrophilicity analysis, based on the NTD region of the S protein. The antigenic index and hydrophilicity plots were obtained using the Jameson-Wolf and Kyte-Doolittle algorithms (28–30), respectively, with the aid of the DNAStar package (DNAStar Inc., Madison, WI, USA). The Kyte-Doolittle method predicts regions of hydrophilicity by summing hydrophilicities over a specified range of amino acids, with an average of nine residues. The Jameson-Wolf method predicts the antigenic index, which produces an index of antigenicity by combining the values for hydrophilicity.

Phylogeography and spatiotemporal analysis.

A total of 219 available and background-clear Asian complete S gene sequences of PEDV were downloaded from GenBank (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). A geographical dissection of the Asian PEDV strains was performed based on the phylogenetic tree of 219 complete S genes. Some PEDV strains had no basic information or available whole-genome or S gene sequences (e.g., some strains from Taiwan and Vietnam) and were not included in this count. The strains were located in the isolated provinces or countries shown on the map in Fig. 4. Note that for strains from China, the location was accurate at the province level, whereas for the others, only the country of origin was known. A time-based geographical dissection of Asian PEDV strains was conducted. On the map, we used four colored spots to distinguish the pandemic group strains, the classic group strains, and the newly sequenced cases of PEDV.

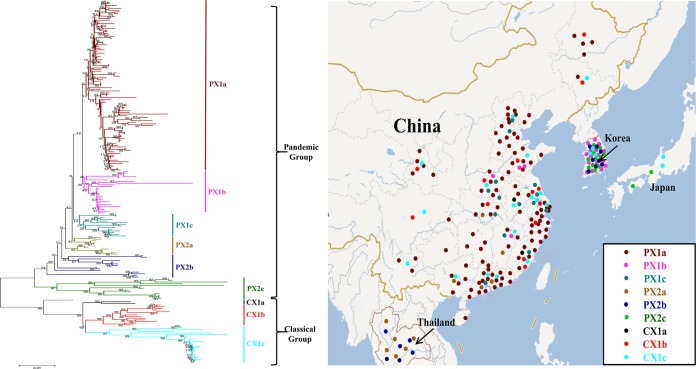

FIG 4.

Map and phylogenetic tree of 219 PEDV S gene sequences. (Left) Phylogeny-based genotyping of 219 PEDV strains with available complete S gene sequences from Asia. The neighbor-joining tree (bootstrap n = 1,000; p-distance) was constructed based on a ClustalW alignment of full-length nucleotide sequences of the S gene. The names of the strains, years, places of isolation, and GenBank accession numbers are shown in Table S3 in the supplemental material. The genogroups and subgroups were proposed according to the above phylogenetic analysis. The pandemic pathotype was divided into six subgroups (PX1a, PX1b, PX1c, PX2a, PX2b, and PX2c) and the classical pathotype into three groups (CX1a, CX1b, and CX1c). (Right) Phylogeny-based geographical dissection of PEDV strains from Asia. A map of Asia shows the districts where PEDV strains with available complete S gene sequences were isolated. The numbers in order and the colors for PEDV strains correspond to those labeled in the left panel.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KM609203 to KM609213.

RESULTS

Whole-genome sequencing.

To reveal the characteristics of this virus and determine more precisely the relationships among the PEDV strains currently circulating in China and other nations, 11 whole genomes of Chinese PEDV isolates collected from different districts at different times were sequenced. All of the whole genomes were 28,038 nucleotides in length, excluding the poly(A) tail. The 11 whole genomes exhibited nucleotide sequence identities ranging from 97.5% to 99.7%, with no insertions or deletions. Their genomic organization was typical of all previously sequenced PEDV strains and was summarized as 5′UTR-ORF1a/1b-S-ORF3-E-M-N-3′UTR (Fig. 1B). The lengths of the seven ORFs were 12,309 bp, 7,638 bp, 4,161 bp, 675 bp, 231 bp, 681 bp, and 1,326 bp, respectively.

Identification of hypervariable regions by whole-genome analysis.

To comprehensively investigate the heterogeneity of PEDV, we performed variation analysis of 49 PEDV whole genomes (11 determined in this study and 38 other available PEDV complete genomes). We identified the four most dissimilar regions, named V1, V2, V3, and V4, respectively (Fig. 1A). In Fig. 1B, the putative variant regions corresponding to functional domains in the PEDV genome are shown below the sequence. V1 comprises the region encoding the C-terminal domain (CTD) of nonstructural protein 2 (nsp2) plus the N-terminal domain (NTD) of nsp3, V2 is in the S1 gene, V3 spans the CTD of the S gene with most of ORF3, and V4 is located in the nucleocapsid (N) gene. V1, V2, V3, and V4 are located on the whole genome of the AH2012 strain (GenBank accession no. KC210145.1) at 1,721 to 3,500 bp, 20,661 to 22,300 bp, 23,541 to 25,200 bp, and 26,741 to 27,700bp, respectively. Note that the NTDs of the S gene and the ORF3 gene were the most obviously different among the four regions.

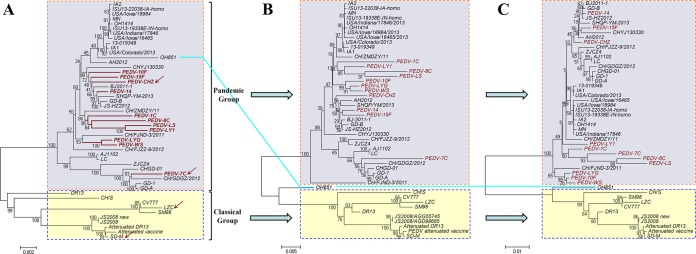

Whole-genomic phylogenetic analysis identified the classical and pandemic groups.

The phylogenetic tree of 49 PEDV genomes indicated that the PEDV isolates could be divided into two clusters, designated the pandemic group and the classical group (Fig. 2A). Thirty-nine Chinese and American strains isolated after 2008 comprised the pandemic group. The classical group comprised 10 strains, including 3 Korean strains (SM98, DR13, and attenuated DR13), 6 Chinese strains (CH/S, LZC, SD-M, attenuated vaccine, JS2008, and JS2008 new), and 1 European strain (CV777). All the strains were isolated before 2008, except strain SD-M (5, 14, 31, 32), and had a rather distant phylogenetic relationship with pandemic group field strains. The 11 isolates first reported in the present study were all clustered into the pandemic group and had a close relationship with Chinese strains isolated after 2008. Among them, the PEDV-LYG and WS strains, collected in 2014, were most closely related to the CH/FJND-3/2011 strain, which was reported as a PEDV variant (33). Only the PEDV-7C strain was closely clustered with the CHGD-01 (26), GD-1 (34), CH/GDGZ/2012 (35), and GD-A (36) strains, which were all isolated in Guangdong province, China.

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic trees of whole PEDV genomes (A), complete S genes encoded in the 49 whole PEDV genomes (B), and the corresponding N-terminal domain (NTD) sequences (C). The three neighbor-joining trees (bootstrap n = 1,000; p-distance) were constructed based on ClustalW alignments of their respective nucleic acid sequences. The sequences in red and branches were revealed for the first time in this study. All three phylogenetic trees were divided into two deep branches, a pandemic branch and a classical branch. The only exception was PEDV isolate OH851, which is linked by blue lines among the three phylogenetic trees.

Identification of regions that distinguished between the classical and pandemic groups (DCP).

To recognize the characteristic gene differences between the classical and pandemic groups, we analyzed the 49 whole-genome sequences. Ultimately, we identified a total of 322 distinctive nucleotides between the pandemic group strains and the classical group strains, based on whole-genome sequencing (data not shown). Among the 322 nt, 79 nt (24.5%) were located in the 1- to 1,179-bp region of the S gene (located on the whole genome of the AH2012 strain at 20,635 to 21,813 bp), and it was the major region that distinguished between the classical and pandemic groups (Fig. 1C). This region, which is included in the V2 region (Fig. 1C), resulted in 49 amino acid changes (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Phylogenetic tree analysis of the whole S gene and the NTD region.

The phylogenetic trees for the full-length S gene and NTD region collectively showed the same grouping structure as the tree generated from the PEDV whole genomes, except for the U.S. strain OH851, which was clustered differently in the trees of the S gene and the NTD region compared with the entire genome tree (Fig. 2). This agreed with a previous study (37). Between the complete genome and the entire S gene tree, there was also some small dissimilarity in the pandemic group, including the AH2012, CH/ZMDZY/11, CH/FJND-3/2011, CH/FJZZ-9/2012, and PEDV-10F strains, whose subgroup distribution changed. The NTD region tree was very similar to the entire S gene tree, except for strain PEDV-7C in the pandemic group. Even though PEDV evolution was not entirely reflected in the analysis of the S gene or NTD region, clustering based on these regions remained an efficient approach for PEDV. Phylogenetic trees based on the V1, V3, and V4 regions did not indicate two distinct genogroups (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), which further showed that the S gene was the best candidate for evaluate the evolutionary relationships of PEDV strains.

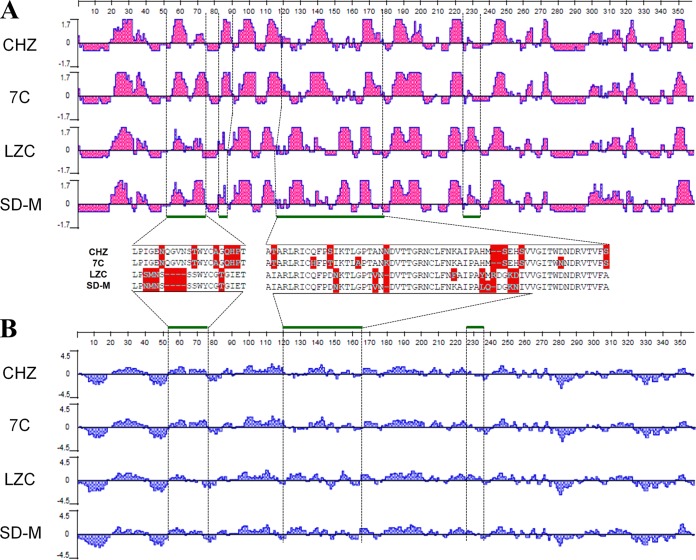

Antigenic index and the hydrophilicity plot analysis of the two PEDV groups.

Four strains (CHZ, 7C, SD-M, and LZC), as representatives, were subjected to further analysis of their antigenic index and the hydrophilicity plot for the NTD (1 to 360 amino acids) of the S protein (Fig. 3). The first two strains were clustered into the pandemic group, and the latter two strains were in the classical group (Fig. 2A). The main antigenic index differences were located at amino acids 53 to 73 and 118 to 179 (Fig. 3A). In addition, the major differences on the hydrophilicity plot were for amino acids 53 to 73 and 118 to 165 (Fig. 3B). These dissimilar regions showed certain point mutations and deletions that differentiated the pandemic group from the classical group.

FIG 3.

Comparison of the antigenic index (A) and hydrophilicity plot (B) of the NTD of S protein fragments between classical and pandemic pathotypes. Dashed and green thick lines, the positions of several regions containing significant differences between classical and pandemic pathotypes. Red shading, mismatched amino acids. PEDV isolates CHZ and 7C belong to the pandemic group, whereas LZC and SD-M isolates are from the classical group.

Genotyping and phylogeny-based geographical dissection of PEDV strains in Asia.

We used 219 available complete S gene sequences, which were isolated from Japan (4 strains), South Korea (39 strains), Thailand (12 strains), and China (204 strains) (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The PEDV strains fell into two distinct groups. The group that included all the strains in the whole-genome pandemic cluster remained and was termed the pandemic group (PX). Similarly, the classical group was termed CX (Fig. 4 left). The PX was further divided into subgroups 1a, 1b, 1c, 2a, 2b, and 2c; and the CX was divided into 1a, 1b, and 1c (Fig. 4 left). From the phylogenetic tree, four subgroups (PX1a, PX1c, CX1a, and CX1b) contained only Chinese field strains. Thai strains were clustered into two subgroups with Chinese or South Korean strains in the pandemic group. The strains in Japan formed subgroups PX2c and CX2c with South Korean or Chinese strains, whereas the South Korean strains were grouped into four subgroups (PX1b, PX2b, PX2c, and CX1c), and the Chinese strains clustered into every subgroup, except PX2b and PX2c (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). The clinical strains from PX1a were the main epidemic subgroup of PEDV outbreaks in China, and PX1b was the main subgroup responsible for outbreaks in South Korea. Interestingly, CX1c contained strains isolated from South Korea, Japan, and China from 1986 to 2013 (see Fig. S4) and was the most complex subgroup.

The possible geographical origins of the 219 PEDV strains were plotted to obtain clues regarding the spread tendency of the emergent PEDV strains in Asia (Fig. 4 right). From the geographical locations, we found that in Japan and Thailand, the common strains were relatively simple, whereas in China, PEDV had spread into every province around the coastal regions, even into Sichuan province or northeast China, since the CH/S strain was isolated in 1986 in Shanghai (31). South Korea also suffered continuous and large-scale outbreaks. Since late 2013, several outbreaks of PEDV infection emerged in Taiwan (38) and Vietnam (39); however, the information on the epidemics was not detailed enough to be analyzed in this study.

Spatiotemporal reconstruction of PEDV strains in Asia.

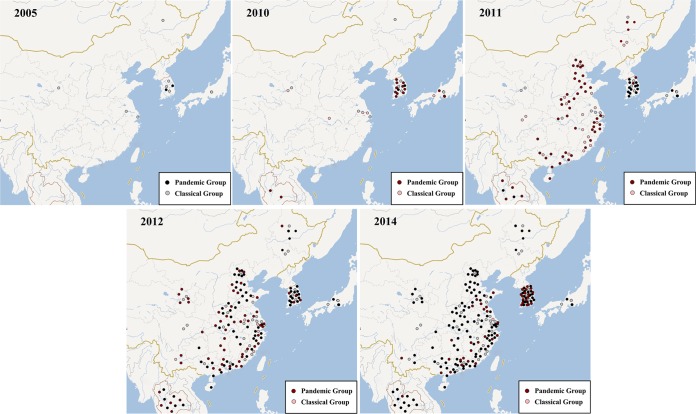

Combining the molecular sequence data with the isolation times and geographical coordinates allowed a spatiotemporal distribution of PEDV to be inferred (Fig. 5; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). By 2005, several occasional epidemics had been reported. All four from China, one from Japan, and three from South Korea were clustered into the classical group. However, two from South Korea were clustered into the pandemic group (Fig. 5), which indicated that the pandemic PEDV in Asia might have originated from South Korea. As of 2010, PEDV was widespread, pandemic group strains emerged in South Korea, and Japan added two pandemic group strains and one classical group strain, whereas China only added four classical group strains (Fig. 5). In addition, there were two pandemic group strains first reported in Thailand (9).

FIG 5.

The reconstructed spatiotemporal diffusion of PEDV at different time points in east Asia. Note that strains in China were located accurately for every province, but the other data only provided the country of origin. Some PEDV strains had no basic information, had no available whole-genome or complete S gene sequence, and were not included in this count (such as some strains from Taiwan and Vietnam). Red and pink plots, newly added strains relative to the previous period.

Between 2010 and 2011, PEDV was continuously detected in various areas in Thailand, and the prevalence of PEDV infections was low and only sporadic outbreaks occurred in South Korea. However, for unclear reasons, a severe PED epizootic was affecting pigs of all ages in many provinces of China, extending into Sichuan and the northeast area of China (Fig. 5). Prevalent PEDV field strains in China were not only distributed in the pandemic group but also represented some clinical strains of the classical group. Between 2012 and 2014, PEDV caused widespread outbreaks in Thailand, South Korea, and China, even extending to Taiwan (38) and Vietnam (39).

DISCUSSION

In recent years, PEDV has continued to cause severe economic damage to the swine industry in Asia. The existing measures, including vaccination, biosecurity, and feedback, cannot effectively block the spread of this disease (2, 14, 40–42). The 11 complete genomes of PEDV field isolates from China determined in this study showed a wide range of genetic variation, which suggested a large risk of PEDV outbreak by novel variants. Comparisons and phylogenetic analysis of 49 PEDV whole genomes (including 12 emerging strains from the United States) confirmed that this issue is also present throughout Asia and in America. Several investigators have reported that the S gene is appropriate to study the genetic relatedness of this virus (14, 15). Here, we attempted to search for variations more accurately through whole-genome analysis and hoped to provide clues to the PEDV evolutionary mechanism.

In this study, four hypervariable regions (V1 to V4) were identified in the whole PEDV genomes, which particularly associated with the PEDV evolutionary process. V1 is located between nsp2 and nsp3, which is considered the putative region of possible recombination events of the US-AH lineage strains (43). V2 is located in the amino terminus of the S protein, which functions as a receptor-binding domain (44). V3 is distributed mainly in the ORF3 gene, which has been used to differentiate between field and vaccine-derived isolates and altered the virulence of PEDV (45). V4 is included in the N gene, which contradicts a previous report that implied that the N gene is highly conserved (46). These differences probably reflect the limited available sequences, small study samples, and analysis of the single N gene in the previous study.

Among the regions, the V2 region (included in the S gene) was the most appropriate to evaluate the evolutionary relationship of PEDV strains and to cluster PEDV strains into the pandemic and classical groups. Further analysis confirmed that the V2 region was suitable to analyze the significant differences in epidemiology between the two groups (2, 9, 47). Thus, the V2 region might play an important role in the genetic evolutionary process of PEDV and will be the focus of future research. The high degree of genetic heterogeneity in the V2 region might explain why the classical vaccine strains cannot effectively control the spread of the pandemic group strains at present. The antigenic index analysis of the V2 region showed enhanced antigenicity in the pandemic group compared with the classical group (43), while none of the known antigen epitope motifs was included in the V2 region (48, 49). These results suggested that some novel neutralizing sites might have formed in the V2 region of the pandemic group strains, which might be associated with their rapid spread and strong pathogenicity (50, 51).

In the phylogenetic tree of the whole genome and the NTD region (included in the V2 region and S gene), the OH851 strain clustered in different groups, which was the only exception. In South Korea, another strain was clustered with strain OH851 (52). These new PEDV variants might originate from a genetic recombination event between pandemic group strains and classical group strains (37). We may still be able to use the S gene to evaluate the evolutionary relationship of PEDV strains and cluster these strains as OH851-like strains, which will require further analysis. Currently, several novel PEDV strains that showed large genomic deletions in the S gene have been isolated in the United States (53) and South Korea (54). These observations suggested that it is critical to monitor PEDV molecular epidemiology continuously.

PEDV has spread into most nations with a swine industry in Asia (2, 9, 23), even being detected in Taiwan (38) and Vietnam (39). Thus, it has spread beyond its geographical limitation. According to the S gene sequences, the 219 PEDV strains in Asia were clustered into pandemic and classical groups. Further subgroup analysis indicated the significant regional differences in the spread of PEDV in different Asian countries. The PX1a, PX1c, CX1a, and CX1c strain subgroups were only epidemic in China, while the PX2b and PX2c subgroups were not detected. All strains isolated after 2013 in South Korea (except KNU/1301/2013 and KNU/1302/2013) were clustered into the PX1b subgroup and formed the main subgroup in South Korea. Notably, to date, a widespread outbreak has not occurred in Japan.

Spatiotemporal reconstruction of PEDV strains showed that South Korean Chinju99, isolated in 1999 (55), is the oldest PEDV pandemic group strain in Asia. The original strains of the pandemic group detected in Japan, Thailand, and China are all homologous with Chinju99, and their genomes have remained relatively stable (51), which implies that the pandemic group strains in Asian countries originated from South Korea. Before 2008, most PEDV field strains belonged to the classical group (Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), but subsequent acute outbreaks in Asia were caused by pandemic group PEDV strains, initially in South Korea (2008) (14) and then in Thailand (2008) (41) and China (2011) (2). Since 2013, the South Korean pandemic strains have become distinct from previous strains and are closely related to Chinese strains isolated after 2011 (see Fig. S4), which indicates that the currently emerging pandemic strains in the PX1b subgroup in South Korea originated from China.

In summary, South Korea and China have undergone the most complex PEDV epidemic situations in the past 5 years. The pandemic group strains in Asia likely originated from South Korea and then spread into Japan, Thailand, and China, successively. However, the pandemic strains that emerged in South Korea after 2013 may have originated from a Chinese variant. In the process of spreading, PEDV underwent numerous genetic variations. In particular, the V2 region plays important roles in PEDV genetic evolution and pathogenicity, which should be investigated further in future research.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a grant from the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02898-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Have P, Moving V, Svansson V, Uttenthal A, Bloch B. 1992. Coronavirus infection in mink (Mustela vison): serological evidence of infection with a coronavirus related to transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Vet Microbiol 31:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90135-G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W, Li H, Liu Y, Pan Y, Deng F, Song Y, Tang X, He Q. 2012. New variants of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, China, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1350–1353. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.120002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sueyoshi M, Tsuda T, Yamazaki K, Yoshida K, Nakazawa M, Sato K, Minami T, Iwashita K, Watanabe M, Suzuki Y, Mori M. 1995. An immunohistochemical investigation of porcine epidemic diarrhoea. J Comp Pathol 113:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9975(05)80069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chasey D, Cartwright SF. 1978. Virus-like particles associated with porcine epidemic diarrhoea. Res Vet Sci 25:255–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pensaert MB, de Bouck P. 1978. A new coronavirus-like particle associated with diarrhea in swine. Arch Virol 58:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01317606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ, Zhang JX, Peiris JS, Chen H, Guan Y. 2007. Evolutionary insights into the ecology of coronaviruses. J Virol 81:4012–4020. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02605-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang DQ, Ge FF, Ju HB, Wang J, Liu J, Ning K, Liu PH, Zhou JP, Sun QY. 2014. Whole-genome analysis of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) from eastern China. Arch Virol 159:2777–2785. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2102-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kocherhans R, Bridgen A, Ackermann M, Tobler K. 2001. Completion of the porcine epidemic diarrhoea coronavirus (PEDV) genome sequence. Virus Genes 23:137–144. doi: 10.1023/A:1011831902219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temeeyasen G, Srijangwad A, Tripipat T, Tipsombatboon P, Piriyapongsa J, Phoolcharoen W, Chuanasa T, Tantituvanont A, Nilubol D. 2014. Genetic diversity of ORF3 and spike genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Thailand. Infect Genet Evol 21:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackwood MW, Hilt DA, Callison SA, Lee CW, Plaza H, Wade E. 2001. Spike glycoprotein cleavage recognition site analysis of infectious bronchitis virus. Avian Dis 45:366–372. doi: 10.2307/1592976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sturman LS, Holmes KV. 1984. Proteolytic cleavage of peplomeric glycoprotein E2 of MHV yields two 90K subunits and activates cell fusion. Adv Exp Med Biol 173:25–35. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9373-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosch BJ, van der Zee R, de Haan CA, Rottier PJ. 2003. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J Virol 77:8801–8811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang SH, Bae JL, Kang TJ, Kim J, Chung GH, Lim CW, Laude H, Yang MS, Jang YS. 2002. Identification of the epitope region capable of inducing neutralizing antibodies against the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Mol Cells 14:295–299. http://www.molcells.org/journal/view.html?year=2002&volume=14&number=2&spage=295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee DK, Park CK, Kim SH, Lee C. 2010. Heterogeneity in spike protein genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses isolated in Korea. Virus Res 149:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Q, Li G, Stasko J, Thomas JT, Stensland WR, Pillatzki AE, Gauger PC, Schwartz KJ, Madson D, Yoon KJ, Stevenson GW, Burrough ER, Harmon KM, Main RG, Zhang J. 2014. Isolation and characterization of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses associated with the 2013 disease outbreak among swine in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 52:234–243. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02820-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SJ, Moon HJ, Yang JS, Lee CS, Song DS, Kang BK, Park BK. 2007. Sequence analysis of the partial spike glycoprotein gene of porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses isolated in Korea. Virus Genes 35:321–332. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S, Lee C. 2014. Outbreak-related porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains similar to US strains, South Korea, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1223–1226. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puranaveja S, Poolperm P, Lertwatcharasarakul P, Kesdaengsakonwut S, Boonsoongnern A, Urairong K, Kitikoon P, Choojai P, Kedkovid R, Teankum K, Thanawongnuwech R. 2009. Chinese-like strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1112–1115. doi: 10.3201/eid1507.081256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spaan W, Cavanagh D, Horzinek MC. 1988. Coronaviruses: structure and genome expression. J Gen Virol 69:2939–2952. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-12-2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Reeth K, Pensaert M. 1994. Prevalence of infections with enzootic respiratory and enteric viruses in feeder pigs entering fattening herds. Vet Rec 135:594–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagy B, Nagy G, Meder M, Mocsari E. 1996. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, rotavirus, porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus, adenovirus and calici-like virus in porcine postweaning diarrhoea in Hungary. Acta Vet Hung 44:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusanagi K, Kuwahara H, Katoh T, Nunoya T, Ishikawa Y, Samejima T, Tajima M. 1992. Isolation and serial propagation of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in cell cultures and partial characterization of the isolate. J Vet Med Sci 54:313–318. doi: 10.1292/jvms.54.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi JC, Lee KK, Pi JH, Park SY, Song CS, Choi IS, Lee JB, Lee DH, Lee SW. 2014. Comparative genome analysis and molecular epidemiology of the reemerging porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains isolated in Korea. Infect Genet Evol 26:348–351. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jinghui F, Yijing L. 2005. Cloning and sequence analysis of the M gene of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus LJB/03. Virus Genes 30:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s11262-004-4583-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishikawa K, Sekiguchi H, Ogino T, Suzuki S. 1997. Direct and rapid detection of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus by RT-PCR. J Virol Methods 69:191–195. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(97)00157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan Y, Tian X, Li W, Zhou Q, Wang D, Bi Y, Chen F, Song Y. 2012. Isolation and characterization of a variant porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in China. Virol J 9:195. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jameson BA, Wolf H. 1988. The antigenic index: a novel algorithm for predicting antigenic determinants. Comput Appl Biosci 4:181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ie SI, Thedja MD, Roni M, Muljono DH. 2010. Prediction of conformational changes by single mutation in the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) identified in HBsAg-negative blood donors. Virol J 7:326. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol 157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Wang C, Shi H, Qiu HJ, Liu S, Shi D, Zhang X, Feng L. 2011. Complete genome sequence of a Chinese virulent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain. J Virol 85:11538–11539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06024-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao M, Sun Z, Zhang Y, Wang G, Wang H, Yang F, Tian F, Jiang S. 2012. Complete genome sequence of a Vero cell-adapted isolate of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in eastern China. J Virol 86:13858–13859. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02674-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J, Liu X, Shi D, Shi H, Zhang X, Feng L. 2012. Complete genome sequence of a porcine epidemic diarrhea virus variant. J Virol 86:3408. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07150-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei ZY, Lu WH, Li ZL, Mo JY, Zeng XD, Zeng ZL, Sun BL, Chen F, Xie QM, Bee YZ, Ma JY. 2012. Complete genome sequence of novel porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain GD-1 in China. J Virol 86:13824–13825. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02615-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian Y, Su D, Zhang H, Chen RA, He D. 2013. Complete genome sequence of a very virulent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strain, CH/GDGZ/2012, isolated in southern China. Genome Announc 1:pii=e00645–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00645-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan H, Zhang J, Ye Y, Tong T, Xie K, Liao M. 2012. Complete genome sequence of a novel porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in south China. J Virol 86:10248–10249. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01589-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Byrum B, Zhang Y. 2014. New variant of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, United States, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 20:917–919. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.140195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin CN, Chung WB, Chang SW, Wen CC, Liu H, Chien CH, Chiou MT. 2014. US-like strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus outbreaks in Taiwan, 2013–2014. J Vet Med Sci 76:1297–1299. doi: 10.1292/jvms.14-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vui DT, Tung N, Inui K, Slater S, Nilubol D. 2014. Complete genome sequence of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Vietnam. Genome Announc 2:pii=e00753–14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00753-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chae C, Kim O, Choi C, Min K, Cho WS, Kim J, Tai JH. 2000. Prevalence of porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus and transmissible gastroenteritis virus infection in Korean pigs. Vet Rec 147:606–608. doi: 10.1136/vr.147.21.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olanratmanee EO, Kunavongkrit A, Tummaruk P. 2010. Impact of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection at different periods of pregnancy on subsequent reproductive performance in gilts and sows. Anim Reprod Sci 122:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowe J, Gauger P, Harmon K, Zhang J, Connor J, Yeske P, Loula T, Levis I, Dufresne L, Main R. 2014. Role of transportation in spread of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 20:872–874. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.131628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang YW, Dickerman AW, Pineyro P, Li L, Fang L, Kiehne R, Opriessnig T, Meng XJ. 2013. Origin, evolution, and genotyping of emergent porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains in the United States. mBio 4:e00737–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00737-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belouzard S, Millet JK, Licitra BN, Whittaker GR. 2012. Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses 4:1011–1033. doi: 10.3390/v4061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park SJ, Moon HJ, Luo Y, Kim HK, Kim EM, Yang JS, Song DS, Kang BK, Lee CS, Park BK. 2008. Cloning and further sequence analysis of the ORF3 gene of wild- and attenuated-type porcine epidemic diarrhea viruses. Virus Genes 36:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0164-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Z, Chen F, Yuan Y, Zeng X, Wei Z, Zhu L, Sun B, Xie Q, Cao Y, Xue C, Ma J, Bee Y. 2013. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of nucleocapsid genes of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) strains in China. Arch Virol 158:1267–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1592-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vlasova AN, Marthaler D, Wang Q, Culhane MR, Rossow KD, Rovira A, Collins J, Saif LJ. 2014. Distinct characteristics and complex evolution of PEDV strains, North America, May 2013–February 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1620–1628. doi: 10.3201/eid2010.140491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cruz DJ, Kim CJ, Shin HJ. 2006. Phage-displayed peptides having antigenic similarities with porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) neutralizing epitopes. Virology 354:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun D, Feng L, Shi H, Chen J, Cui X, Chen H, Liu S, Tong Y, Wang Y, Tong G. 2008. Identification of two novel B cell epitopes on porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike protein. Vet Microbiol 131:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian Y, Yu Z, Cheng K, Liu Y, Huang J, Xin Y, Li Y, Fan S, Wang T, Huang G, Feng N, Yang Z, Yang S, Gao Y, Xia X. 2013. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of new variants of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in Gansu, China in 2012. Viruses 5:1991–2004. doi: 10.3390/v5081991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun R, Leng Z, Zhai SL, Chen D, Song C. 2014. Genetic variability and phylogeny of current Chinese porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains based on spike, ORF3, and membrane genes. ScientificWorldJournal 2014:208439. doi: 10.1155/2014/208439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee S, Park GS, Shin JH, Lee C. 2014. Full-genome sequence analysis of a variant strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in South Korea. Genome Announ 2:pii=e01116-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01116-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oka T, Saif LJ, Marthaler D, Esseili MA, Meulia T, Lin CM, Vlasova AN, Jung K, Zhang Y, Wang Q. 2014. Cell culture isolation and sequence analysis of genetically diverse US porcine epidemic diarrhea virus strains, including a novel strain with a large deletion in the spike gene. Vet Microbiol 173:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park S, Kim S, Song D, Park B. 2014. Novel porcine epidemic diarrhea virus variant with large genomic deletion, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis 20:2089–2092. doi: 10.3201/eid2012.131642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeo SG, Hernandez M, Krell PJ, Nagy EE. 2003. Cloning and sequence analysis of the spike gene of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus Chinju99. Virus Genes 26:239–246. doi: 10.1023/A:1024443112717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.