Abstract

Genetic and antigenic characterization of 37 representative influenza A(H3N2) virus strains isolated in Greece during the 2011-2012 winter season was performed to evaluate matching of the viruses with the seasonal influenza vaccine strain A/Perth/16/2009. Hemagglutinin gene sequence analysis revealed that all Greek strains clustered within the Victoria/208 genetic clade. Furthermore, substitutions in the antigenic and glycosylation sites suggested potential antigenic drift. Our hemagglutination inhibition (HI) analysis showed that the Greek viruses were Perth/16-like; however, these viruses were characterized as Victoria/208-like when tested at the United Kingdom WHO Collaborating Centre (CC) with HI assays performed in the presence of oseltamivir, a finding consistent with the genetic characterization data. Variability in the HI test performance experienced by other European laboratories indicated that antigenic analysis of the A(H3N2) virus has limitations and, until its standardization, national influenza reference laboratories should include genetic characterization results for selection of representative viruses for detailed antigenic analysis by the WHO CCs.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza virus is an important causative agent of respiratory tract infections, and annual influenza epidemics have a significant impact on global public health (1). There are two main types of influenza viruses infecting humans, namely, types A and B. Type A viruses can be subtyped according to the antigenic properties of their hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) surface glycoproteins (2, 3). Currently circulating subtypes of seasonal influenza type A viruses are A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2).

Vaccination is the major protective barrier against outbreaks of influenza respiratory disease. However, seasonal circulating influenza viruses exploit the genetic instability of viral HA to escape immune responses and to avoid matching with homologous vaccine viruses, thus forcing annual evaluation of vaccine effectiveness (4). The HA glycoprotein mediates viral entry into host cells and is the major antigenic target for neutralizing antibodies induced by vaccines. Host cell proteases cleave HA into two domains, i.e., HA1 (the unique component of the viral HA globular head) and HA2 (the stalk and anchor in the cell membrane) (5). The HA1 domain contains the receptor binding cavity as well as major antigenic sites of the HA molecule; therefore, acquisition of substitutions within this region has the greatest effect on the viral antigenic structure.

Seasonal influenza virus A(H3N2) is a typical example of a vaccine escape virus. Since the H3N2 pandemic in 1968, 108 amino acid changes have clustered at 63 residue positions in HA1, resulting in 27 A(H3N2) strain alterations in the vaccine formulation, twice as many as for the other vaccine components [influenza type B or former A(H1N1) strains] (6). The majority of these changes were clustered at the viral antigenic sites, which were previously named antigenic sites A to E in A(H3N2) viruses (7–9). Previous genetic analyses of Greek influenza A(H3N2) viruses from 2004 through 2008 indicated the emergence of variations at antigenic and glycosylation sites of the HA1 domain (10).

Genetic analysis of the viral HA1 domain and antigenic analysis of viruses are important tools for the identification of circulating viruses with characteristics that might lead to vaccine failure. Both laboratory-based activities are carried out by the National Influenza Reference Centers (NICs) and the WHO Collaborating Centers (CCs) for Reference and Research on Influenza in order to examine the molecular evolution of influenza viruses and its impact on antigenic characteristics, thus contributing to the evaluation of each year's vaccine and the recommendations for the following year's vaccine candidates (11). The aims of the present study were molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of representative influenza A(H3N2) strains that circulated in Greece during peak influenza activity in the 2011-2012 season, as well as identification of antigenic and genetic variations, compared with the vaccine and other reference strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Influenza cases and specimens.

During the 2011-2012 winter season, the presence of influenza virus RNA was detected by multiplex real-time reverse transcription-PCR in 890 (49.3%) of 1,806 respiratory specimens from patients with influenza-like illness (ILI), 441 (24.4%) of which were positive for influenza A(H3N2) virus; the remaining 449 specimens (24.9%) were found to be positive for influenza B virus. The first and last positive A(H3N2) cases were confirmed on 8 January 2012 (week 1) and 18 April 2012 (week 16), respectively. During the same period, only a single case positive for A(H1N1)pdm09 was confirmed.

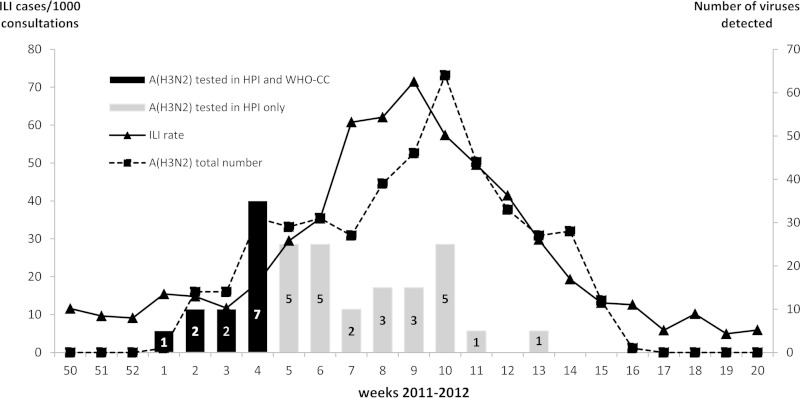

The influenza virus A(H3N2) strains included in the study were selected from the 2011-2012 A(H3N2)-positive group according to criteria recommended by the WHO for selection of sufficient representative viruses for characterization studies and shipment to the WHO CC (London, United Kingdom) (12). In total, 37 influenza A(H3N2)-positive specimens with high viral loads (PCR threshold cycle [CT] values of <30) were selected, accounting for approximately 10% of the A(H3N2)-positive specimens. Eighteen specimens were selected from among the specimens sent by the sentinel physicians, to ensure spatiotemporal representativeness. The remaining 19 specimens originated from hospitalized patients or intensive care unit (ICU) cases. Five to seven specimens were selected from each of the following age groups: 0 to 1 years, 2 to 5 years, 6 to 18 years, 19 to 35 years, 36 to 65 years, and >65 years. Sixteen (43%) of the 37 specimens were selected through the end of January 2012, while the remaining 21 specimens (57%) were collected during progression of the influenza outbreak through April 2012 (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Weekly distribution of the isolation of the 37 influenza A(H3N2) viruses selected for genetic and antigenic characterization. Dashed line (◼), total numbers of clinical specimens positive for A(H3N2) (right vertical axis); solid line (▲), rate of influenza-like illness (ILI) cases in the 2011-2012 influenza season (left vertical axis). Black bars, specimens tested by both the Greek NIC (HPI) and the WHO CC; gray bars, specimens tested by only the Greek NIC. The numbers of viruses tested are shown on each bar.

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses.

For sequence analysis, a 1,096-bp DNA fragment of the HA1 domain was amplified directly from the clinical samples by an in-house nested-PCR protocol. Primer sequences for PCR and sequencing had been published by WHO CCs in the European Influenza Surveillance Network (EISN) protocol library, with restricted access among the NICs. The resulting amplicons were purified by utilizing the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the MinElute gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and were sequenced in both directions by using the GenomeLab DTCS Quick Start sequencing kit (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) with a CEQTM 8000 genetic analyzer (Beckman Coulter).

Multiple-sequence alignment of the sequences obtained and of those of influenza virus reference strains retrieved from GenBank and the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) was performed using the BioEdit sequence alignment editor (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the MEGA program, version 5 (13). The neighbor-joining method (tree algorithm inferred with the Kimura 2-parameter substitution model of sequence evolution) (14, 15) was used to construct phylogenetic trees, and bootstrap resampling analysis was performed (1,000 replicates) to test tree reliability (16). In order to identify the presence of new N-linked glycosylation sites, the aforementioned sequences were also screened for the consensus asparagine-X-serine/threonine (NXS/T) motif (X is any amino acid except proline).

Antigenic analysis.

All 37 A(H3N2) strains included in the study were inoculated in MDCK SIAT-1 cells. Thirty of them had sufficient titers and were compared to the 2011-2012 A/Perth/16/2009 seasonal influenza H3N2 vaccine component for antigenic relatedness by the hemagglutination inhibition (HI) method, according to WHO recommendations (17). For HI testing, a reference ferret antiserum raised against the egg-grown 2011-2012 vaccine virus A/Perth/16/2009, kindly provided by the WHO CC in the United Kingdom, was used with guinea pig red blood cells (RBCs) (1% [vol/vol] standardized solution) obtained from the animal unit of the Hellenic Pasteur Institute. The latter reference antiserum was treated with receptor-destroying enzyme according to WHO CC standard procedures.

For a virus isolate to be considered like a vaccine/reference virus, its HI titer with the reference ferret antiserum should differ by no more than 4-fold (usually a decrease), in a 2-fold dilution series, from the HI titer with the vaccine/reference virus itself. The HI titers were the reciprocals of the highest dilution at which virus binding to guinea pig RBCs was blocked.

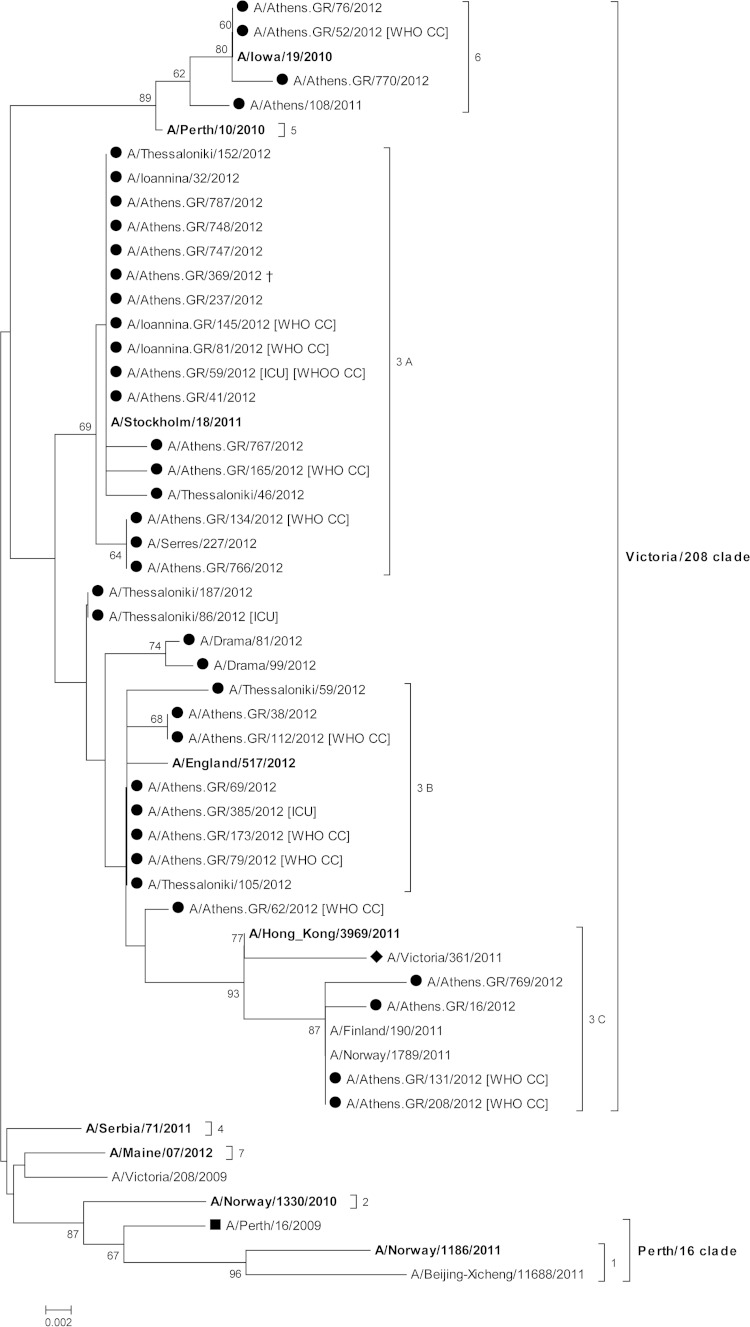

Further detailed antigenic characterization was performed with a subset of the aforementioned strains (n = 12), by the WHO CC in the United Kingdom. These strains were selected at the beginning phase of the seasonal epidemic and were of extensive genetic variation, as demonstrated by HA sequence analysis (Fig. 2). HI analysis by the WHO CC was performed using the aforementioned reference antiserum and other ferret antisera raised against cell-grown representative European strains. The HI protocol utilized by the WHO CC included the addition of 20 nM oseltamivir carboxylate in the assay plates to prevent hemagglutination by binding through the neuraminidase. Preliminary testing in our laboratory to implement HI analysis in the presence of oseltamivir carboxylate according to WHO CC standard procedures resulted in very low hemagglutination titers, which prevented its use for HI assays.

FIG 2.

Evolutionary relationships of Greek influenza A(H3N2) strains (●) with recent European reference and vaccine strains, based on the HA1 domain of the HA protein gene segment. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. Only values above 60% are shown. Strains from the 2011-2012 influenza season (◼) and the 2012-2013 influenza season vaccine (◆) are depicted. Reference strains are indicated in bold. A cross symbol ( ) designates a fatal case.

) designates a fatal case.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences obtained in this study were deposited in the GISAID database under accession numbers EPI354678, EPI354681 to EPI354689, EPI358885, EPI358887, EPI358889, EPI358891, EPI358893, EPI358945, EPI368826, EPI368828, EPI369758, EPI369786, EPI359554 to EPI359560, EPI475780, EPI475800, EPI475811, EPI475813, and EPI475819 to EPI475824.

RESULTS

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic analysis indicated clustering of the Greek strains within genetic groups 3A (46.0%), 3B (35.1%), 3C (10.8%), and 6 (8.1%), all belonging to the Victoria/208 clade (Fig. 2). Genetic groups were assigned by the WHO CC in the United Kingdom in 2011-2012 genetic studies (18). All A(H3N2) sequences revealed HA nucleotide identities of 97.1 to 100% and deduced amino acid identities of 95.5 to 100% with each other. The aforementioned strains were also compared with the 2011-2012 influenza season vaccine strain for the Northern hemisphere, A/Perth/16/2009, and exhibited nucleotide identities of 97.4 to 98.5% and deduced amino acid identities of 95.8 to 97.8%. Interestingly, none of the Greek strains clustered with vaccine strain A/Perth/16/2009 in the same genetic clade (Perth/16 clade).

HA1 sequencing of the 2011-2012 A(H3N2) strains revealed a total of 19 amino acid variations at the five viral antigenic sites (sites A, B, C, D, and E), compared with the vaccine strain A/Perth/16/2009 (Table 1). Strains belonging to group 3A accumulated 2 amino acid variations at antigenic site A, 3 at site D, and 1 or 2 at site E; strains belonging to group 3B possessed 2 amino acid variations at antigenic site A, 1 at site B, 0 to 2 at site C, 3 at site D, and 1 at site E; strains belonging to group 3C accumulated 1 amino acid variation at antigenic site A, 1 at site B, 4 at site C, 3 at site D, and 1 at site E; finally, strains belonging to group 6 revealed 1 amino acid variation at antigenic site A, 2 at site C, 3 or 4 at site D, and 2 at site E. The most divergent strain, A/Athens/16/2012, belonged to group 3C and revealed the emergence of 4 amino acid substitutions at 2 different antigenic sites (sites C and D).

TABLE 1.

Amino acid substitutions observed at antigenic sites and N-linked glycosylation sites of HA

| Strain and description | Sequence data | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycosylation site | + | + | − | |||||||||||||||||||

| Antigenic site | C | C | C | C | E | E | E | A | A | A | B | D | D | D | D | D | C | C | C | |||

| Position | 33 | 45 | 48 | 53 | 54 | 62 | 92 | 94 | 144 | 144 | 145 | 183 | 198 | 199 | 212 | 214 | 223 | 227 | 230 | 278 | 280 | 312 |

| Amino acid | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A/Perth/16/2009a | Q | S | T | D | S | K | K | Y | K | K | N | L | A | S | T | S | V | P | I | N | E | N |

| Group 3C (2 gains) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/769/2012 | R | N | I | E | N | − | H | S | A | T | I | K | S | |||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/16/2012 | R | N | I | E | N | − | H | S | A | I | I | H | K | S | ||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/208/2012 | R | N | I | E | N | − | H | S | A | I | I | K | S | |||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/131/2012 | R | N | I | E | N | − | H | S | A | I | I | K | S | |||||||||

| A/Finland/190/2011b | R | N | I | E | N | − | H | S | A | I | I | K | S | |||||||||

| Group 3B (1 gain) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/62/2012 | K | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | |||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/69/2012 | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | ||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/385/2012 | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | ||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/173/2012 | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | ||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/79/2012 | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | ||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/38/2012 | R | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | |||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/112/2012 | R | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | |||||||||||

| A/Thessaloniki/105/2012 | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | ||||||||||||

| A/Thessaloniki/59/2012 | G | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | ||||||||||||

| A/Thessaloniki/187/2012 | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | |||||||||||||

| A/Thessaloniki/86/2012 | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | |||||||||||||

| A/Drama/99/2012 | N | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | |||||||||||

| A/Drama/81/2012 | N | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | ||||||||||||

| A/England/259/2011b | A | E | N | − | S | H | S | A | I | I | S | |||||||||||

| Group 3A (1 loss) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/134/2012 | E | H | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | |||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/766/2012 | E | H | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | |||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/41/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/59/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Ioannina.GR/81/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Ioannina.GR/145/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/165/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/237/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/369/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/747/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/748/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/767/2012 | E | R | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | |||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/787/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Thessaloniki/46/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Thessaloniki/152/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Ioannina/32/2012 | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| A/Serres/227/2012 | E | H | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | |||||||||||||

| A/Stockholm/18/2011b | E | − | D | S | H | A | I | I | ||||||||||||||

| Group 6 (1 gain) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/52/2012 | N | E | H | N | − | H | A | A | I | V | A | |||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/770/2012 | N | E | H | N | − | H | A | A | I | L | V | A | ||||||||||

| A/Athens.GR/76/2012 | N | E | H | N | − | H | A | A | I | V | A | |||||||||||

| A/Iowa/19/2010b | N | E | H | N | − | H | A | A | I | V | A | |||||||||||

The comparisons were performed using the H3N2 vaccine strain for the 2011-2012 season. The amino acid substitutions are shown using the one-letter amino acid code.

Reference strain.

Following the molecular analysis of HA1 of circulating strains, variations were also observed in the N-linked glycosylation sites. Substitution of lysine with aspartic acid at position 144 in 17 Greek strains, all belonging to group 3A, resulted in the loss of a glycosylation site. In contrast, substitution of lysine with asparagine at the same position in 20 other strains, belonging to groups 3B, 3C, and 6, resulted in the gain of a glycosylation site. In the 4 strains belonging to group 3C, substitution of serine with asparagine at position 45 resulted in the gain of another glycosylation site (Table 1).

No particular segregation of sequences according to epidemic timeline (beginning, peak, or end of ILI consultations) was observed (data not shown). All strains belonging to groups 3A, 3B, and 6 circulated during the peak of the season (weeks 4 to 11, weeks 3 to 10, and weeks 4 to 10, respectively), whereas strains belonging to group 3C were detected 2 to 3 weeks earlier (weeks 1 to 10) but cocirculated with the other groups from 2012 week 3 onward.

Viral strains identified from ICU cases, as well as the A/Athens.GR/369/2012 viral strain originating from the single fatal case included in the study, were closely related to the other Greek strains examined at the genetic level (Fig. 2). Finally, all strains allocated to genetic group 3C were obtained from hospitalized patients and exhibited more amino acid alterations at antigenic and glycosylation sites than did the rest of the viruses.

Antigenic analysis.

HI testing without oseltamivir revealed that 19 (63.3%) of 30 viruses had HI titers of 1:640 and the remaining 11 had HI titers of 1:320 against the reference antiserum raised against egg-propagated strain A/Perth/16/2009, while the homologous reaction of the egg-propagated vaccine strain A/Perth/16/2009 with the same reference antiserum demonstrated a titer of 1:1,280. Thus, all 30 virus isolates showed not more than 4-fold reductions in HI reactivity, compared to the vaccine reference virus, and they were characterized as A/Perth/16/2009-like, despite phylogenetic allocation of these viruses to the Victoria/208 clade. Twelve viruses, representing genetic variations within groups 3A, 3B, and 3C of the Victoria/208 clade, were further analyzed by the WHO CC in the United Kingdom (Table 2). In contrast to our results, antigenic analysis in HI testing with oseltamivir illustrated poor reactivity with the reference antiserum raised against egg-propagated strain A/Perth/16/2009, with titers reduced 8-fold, compared with the homologous titer, suggesting that the 12 viruses were indeed antigenically not A/Perth/16/2009-like. In accordance with our phylogenetic analysis, however, all isolates exhibited ≤4-fold titer reductions, compared with cell-propagated reference viruses of the Victoria/208 clade that had been isolated in Europe.

TABLE 2.

Hemagglutination inhibition testing results for Greek strains using the postinfection ferret antiserum raised against the egg-grown 2011-2012 vaccine virus A/Perth/16/2009a

| Virus tested | Collection date (yr-mo-day) | HI titerc |

Genetic group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greek NIC | WHO CC | |||

| A/Perth/16/2009b | 2009-7-4 | 1,280 | 1280 | 1 |

| A/Athens.GR/79/2012 | 2012-1-26 | 640 | 80 | 3B |

| A/Ioannina.GR/81/2012 | 2012-1-26 | 640 | 80 | 3A |

| A/Ioannina.GR/145/2012 | 2012-1-30 | 640 | 80 | 3A |

| A/Athens.GR/165/2012 | 2012-2-4 | 320 | 80 | 3A |

| A/Athens.GR/173/2012 | 2012-2-6 | 640 | 80 | 3B |

| A/Athens.GR/59/2012 | 2012-1-23 | 320 | 80 | 3A |

| A/Athens.GR/112/2012 | 2012-2-1 | 640 | 80 | 3B |

| A/Athens.GR/131/2012 | 2012-2-2 | 320 | 80 | 3C |

| A/Athens.GR/134/2012 | 2012-2-2 | 640 | 80 | 3A |

| A/Athens.GR/62/2012 | 2012-1-23 | 320 | 80 | 3B |

| A/Athens.GR/208/2012 | 2012-2-4 | 320 | 80 | 3C |

| A/Athens.GR/52/2012 | 2012-1-25 | 320 | 160 | 6 |

HI testing was performed by both laboratories using a 1% guinea pig red blood cell solution, without oseltamivir at the Greek NIC and in the presence of oseltamivir at the WHO CC. MDCK SIAT-1 cells were used by both laboratories for propagation of the Greek viruses.

The vaccine virus A/Perth/16/2009 was grown in eggs by the WHO CC and in MDCK SIAT-1 cells by the Greek NIC.

The HI titer is shown as the reciprocal of the postinfection ferret antiserum dilution.

DISCUSSION

Antigenic characterization supported by gene sequencing of HA and NA genes of influenza viruses performed by NICs is the cornerstone of influenza risk assessment and development of seasonal influenza vaccines. Selection of representative strains for testing is a critical step for this task. We selected 37 A(H3N2) viruses from the 2011-2012 winter influenza season, among a large number of clinical specimens that were positive for A(H3N2) virus, for characterization. The selection was based on the criteria recommended by the WHO to select sufficient representative viruses for characterization studies and shipment to the WHO CC (12). Sixteen (43%) of the aforementioned specimens were selected through the end of January 2012, since timely genetic and antigenic characterization of the viruses isolated at the beginning of the influenza season and their prompt shipment to the WHO CC for further characterization are critical for the WHO consultation on the Northern Hemisphere vaccine composition in February. However, the percentage of specimens required for virus isolation and characterization is not addressed in the WHO guidelines. Each NIC laboratory should choose an algorithm, based on the WHO selection criteria, that best fits laboratory test flow, surveillance needs, resources, and laboratory capacity.

Phylogenetic analysis of the influenza A(H3N2) viruses examined during the 2011-2012 winter season in Greece revealed the circulation of viral strains that did not cluster in the Perth/16 clade (represented by the A/Perth/16/2009 vaccine strain) but clustered in 4 different genetic groups within the Victoria/208 clade, predominantly group 3 (91.9%). During the same period, all countries within the European Influenza Surveillance Network reported the circulation of A(H3N2) viruses that were genetically different from the vaccine strain (19, 20). The majority of those strains belonged to group 3 of the Victoria/208 clade.

Each one of the examined strains displayed at least 4 alterations in 3 antigenic sites, with the most divergent strain, A/Athens/16/2012, possessing 4 amino acid substitutions in 2 different antigenic sites. Genetic analysis of the HA1 domain is important, as it has been shown that amino acid changes within the antigenic sites can significantly affect the antigenic properties of influenza viruses and cumulatively enhance antigenic drift (5, 21, 22). Particularly interesting are amino acid substitutions in antigenic sites localized around the receptor binding pocket, such as sites A and B. It is noteworthy that the hemagglutinins of antigenically distinct viruses of epidemic significance have substitutions in positions 140 to 146 of antigenic site A (7, 8, 21). The K144N/D substitution has been confirmed in all Greek A(H3N2) strains examined. The majority of the strains also contained the N145S substitution within this region. Moreover, HA1 amino acid sequence analysis showed an altered potential N-linked glycosylation site at amino acid 144 in all Greek strains. Amino acid alterations within the relatively conserved N-linked glycosylation sites of viral HA may alter the antigenicity and virulence of influenza virus by shielding the major antigenic epitopes (23).

The aforementioned genetic variations indicated potential antigenic drift for all strains examined. Despite that, preliminary antigenic characterization performed by our laboratory did not show that emerging genetic variants were antigenically different from the A/Perth/16/2009 vaccine strain. Similarly, all European countries reported the circulation of Perth/16-like viruses, as determined by antigenic characterization (24). In detailed antigenic studies carried out by the WHO CC, Greek strains demonstrated reduced reactivity (≥8-fold) with ferret antiserum raised against the egg-grown vaccine virus A/Perth/16/2009. These studies, performed by HI testing in the presence of oseltamivir carboxylate, efficiently detected the antigenic variants and were in agreement with the genetic characterization studies (25). It seems that, apart from HA, viral NA of A(H3N2) viruses also interacts with the erythrocytes used in HI testing; to circumvent this interaction, Lin et al. recommended that HI assays should be carried out in the presence of oseltamivir (26). The agglutination of RBCs by viral NA has been shown to be the result of substitution of aspartic acid 151 of NA by glycine, asparagine, or alanine (26). NA gene sequence analysis of the 12 Greek isolates was carried out by the WHO CC (data not shown). Interestingly, no neuraminidase receptor binding variants of Greek influenza A(H3N2) viruses resulting from substitution of aspartic acid 151 in the catalytic site were confirmed.

In contrast to WHO CC findings, the addition of oseltamivir in our HI testing prevented the antigenic assessment of viral HA due to low hemagglutination titers. The overall reduced sensitivity of our MDCK SIAT-1 cells, compared to the WHO CC MDCK SIAT-1 cell cultures, the level of optimization of our HI testing in the presence of oseltamivir, and slight differences in cell lines, guinea pig red blood cells, and batches of the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir could account for the resulting assay limitations. It is noteworthy that significant variability in HI testing using oseltamivir has been reported recently by the WHO (27). Use of the provided ferret antiserum raised against the egg-grown 2011-2012 vaccine virus to antigenically characterize cell-grown H3N2 viruses may be of additional concern. It is known that, when a human influenza virus is adapted to growth in eggs, it undergoes phenotypic changes, which might include changes in its antigenicity/immunogenicity (28). Nevertheless, the evolving nature of H3N2 HA receptor binding necessitated the addition of oseltamivir even when ferret antisera raised against cell-grown viruses were used in HI testing (26).

Unlike in the 2011-2012 influenza season included in the study, both genetic and antigenic testing without oseltamivir were effective for monitoring Greek strains fit to the respective seasonal vaccine strains during the 2012-2013 and 2013-2014 influenza seasons. Other European countries also reported that circulating viruses were genetically and antigenically similar to the vaccine strains (29, 30). These findings may be explained by the fact that the H3N2 viruses were antigenically conserved. If circulating viruses of the 2012-2013 and 2013-2014 influenza seasons had exhibited antigenically significant genetic variations, then HI assays without oseltamivir could misinterpret agglutination patterns and miss antigenic drift. Difficulties in HI testing reemerged during the 2014-2015 influenza season, due to the failure of a proportion of the circulating H3N2 viruses to agglutinate guinea pig or other red blood cells (J. McCauley, WHO CC, personal communication).

The challenges experienced in the antigenic characterization of the 2011-2012 H3N2 viruses by HI testing, with or without oseltamivir, necessitate HI assay standardization. Until that occurs, national influenza reference laboratories should not rely solely on HI assay results for selection of representative viruses for detailed antigenic analysis by WHO CCs but should include genetic characterization results in that assessment. Timely detection of substitutions within the antigenic sites would facilitate the selection of “interesting and risky” viruses that should be sent to the WHO CC for detailed antigenic characterization. In this way, the shipment of numerous specimens and WHO CC overload prior to the vaccine recommendation decisions could be avoided. Boosting of genetic analysis would require timely sharing of related metadata, both clinical and epidemiological. This emerging requirement for vaccine virus selection could be fulfilled through submission of genetic data to genetic databases such as the publicly accessible GISAID platform.

Increased difficulties in antigenic characterization might be overcome by the integration of technical improvements such as the use of erythrocyte substitutes to select exclusively for the viral HA glycoprotein (27). Even more promising is the identification of antigenic variants using sequence data alone, based on high-throughput genetic sequencing combined with advanced bioinformatics tools (31). At this time, however, traditional methods should not be discontinued. Antigenic characterization limitations have not been observed for influenza B viruses and other influenza type A viruses, such as A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, and NICs should continue to perform virus propagation and HI testing for those viruses. Moreover, virus isolates, including H3N2, are needed not only for antigenic characterization studies but also for other NIC activities, such as phenotypic antiviral susceptibility testing and probably high-throughput sequencing techniques.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank John McCauley, Rod Daniels, Yipu Lin, Vicky Gregory, and all of their colleagues at the WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza at the MRC National Institute for Medical Research (London, United Kingdom) for their efforts in testing and analyzing our influenza viruses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fiore AE, Uyeki TM, Broder K, Finelli L, Euler GL, Singleton JA, Iskander JK, Wortley PM, Shay DK, Bresee JS, Cox NJ. 2010. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 59(RR-8):1–62. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5908.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2010. Influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase membrane glycoproteins. J Biol Chem 285:28403–28409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.129809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medina RA, Garcia-Sastre A. 2011. Influenza A viruses: new research developments. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:590–603. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. 2012. Vaccines against influenza. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 87:461–476. http://www.who.int/wer/2012/wer8747.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih AC, Hsiao TC, Ho MS, Li WH. 2007. Simultaneous amino acid substitutions at antigenic sites drive influenza A hemagglutinin evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:6283–6288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701396104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popova L, Smith K, West AH, Wilson PC, James JA, Thompson LF, Air GM. 2012. Immunodominance of antigenic site B over site A of hemagglutinin of recent H3N2 influenza viruses. PLoS One 7:e41895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiley DC, Wilson IA, Skehel JJ. 1981. Structural identification of the antibody-binding sites of Hong Kong influenza haemagglutinin and their involvement in antigenic variation. Nature 289:373–378. doi: 10.1038/289373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush RM, Bender CA, Subbarao K, Cox NJ, Fitch WM. 1999. Predicting the evolution of human influenza A. Science 286:1921–1925. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skehel JJ, Stevens DJ, Daniels RS, Douglas AR, Knossow M, Wilson IA, Wiley DC. 1984. A carbohydrate side chain on hemagglutinins of Hong Kong influenza viruses inhibits recognition by a monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:1779–1783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melidou A, Exindari M, Gioula G, Chatzidimitriou D, Pierroutsakos Y, Diza-Mataftsi E. 2009. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis and vaccine strain match of human influenza A(H3N2) viruses isolated in northern Greece between 2004 and 2008. Virus Res 145:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitler ME, Gavinio P, Lavanchy D. 2002. Influenza and the work of the World Health Organization. Vaccine 20(Suppl 2):S5–S14. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. 2010. Selection of clinical specimens for virus isolation and of viruses for shipment from National Influenza Centres to WHO Collaborating Centres: 6 December 2010. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/influenza/gisrs_laboratory/national_influenza_centres/20101206_specimens_selected_for_virus_isolation_and_shipment.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network. 2011. Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance of influenza. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241548090_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza. 2013. Report prepared for the WHO annual consultation on the composition of influenza vaccine for the Southern Hemisphere 2013. National Institute for Medical Research, London, United Kingdom: http://www.nimr.mrc.ac.uk/documents/about/Interim_Report_September_2012_2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pariani E, Amendola A, Ebranati E, Ranghiero A, Lai A, Anselmi G, Zehender G, Zanetti A. 2013. Genetic drift influenza A(H3N2) virus hemagglutinin (HA) variants originated during the last pandemic turn out to be predominant in the 2011-2012 season in northern Italy. Infect Genet Evol 13:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2012. Main surveillance developments in weeks 27-28, 2012 (2-15 July 2012). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, Sweden: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/120720-SUR-WISO.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koel BF, Burke DF, Bestebroer TM, van der Vliet S, Zondag GC, Vervaet G, Skepner E, Lewis NS, Spronken MI, Russell CA, Eropkin MY, Hurt AC, Barr IG, de Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA, Smith DJ. 2013. Substitutions near the receptor binding site determine major antigenic change during influenza virus evolution. Science 342:976–979. doi: 10.1126/science.1244730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson IA, Cox NJ. 1990. Structural basis of immune recognition of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Immunol 8:737–771. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tate MD, Job ER, Deng YM, Gunalan V, Maurer-Stroh S, Reading PC. 2014. Playing hide and seek: how glycosylation of the influenza virus hemagglutinin can modulate the immune response to infection. Viruses 6:1294–1316. doi: 10.3390/v6031294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2012. Main surveillance developments in week 8/2012 (20-26 Feb 2012). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, Sweden: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/120302-SUR-weekly-influenza-surveillance-overview.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza. 2012. Report prepared for the WHO annual consultation on the composition of influenza vaccine for the Southern Hemisphere 2013. National Institute for Medical Research, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin YP, Gregory V, Collins P, Kloess J, Wharton S, Cattle N, Lackenby A, Daniels R, Hay A. 2010. Neuraminidase receptor binding variants of human influenza A(H3N2) viruses resulting from substitution of aspartic acid 151 in the catalytic site: a role in virus attachment? J Virol 84:6769–6781. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00458-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ampofo WK, Al Busaidy S, Cox NJ, Giovanni M, Hay A, Huang S, Inglis S, Katz J, Mokhtari-Azad T, Peiris M, Savy V, Sawanpanyalert P, Venter M, Waddell AL, Wickramasinghe G, Zhang W, Ziegler T. 2013. Strengthening the influenza vaccine virus selection and development process: outcome of the 2nd WHO Informal Consultation for Improving Influenza Vaccine Virus Selection held at the Centre International de Conferences (CICG) Geneva, Switzerland, 7 to 9 December 2011. Vaccine 31:3209–3221. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schild GC, Oxford JS, de Jong JC, Webster RG. 1983. Evidence for host-cell selection of influenza virus antigenic variants. Nature 303:706–709. doi: 10.1038/303706a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza. 2013. Report prepared for the WHO annual consultation on the composition of influenza vaccine for the Northern Hemisphere 2013/14. National Institute for Medical Research, London, United Kingdom: http://www.nimr.mrc.ac.uk/documents/about/Interim_Report_February_2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza. 2014. Report prepared for the WHO annual consultation on the composition of influenza vaccine for the Northern Hemisphere 2014/15. National Institute for Medical Research, London, United Kingdom: http://www.nimr.mrc.ac.uk/documents/about/NIMR-report-Feb2014-web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun H, Yang J, Zhang T, Long L, Jia K, Yang G, Webby R, Wan X. 2013. Using sequence data to infer the antigenicity of influenza virus. mBio 4(4):e00230-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00230-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]