Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSI) are classified epidemiologically as health care-associated hospital onset (HAHO)-, health care-associated community onset (HACO)-, or community-associated (CA)-MRSA. Clinical and molecular differences between HAHO- and HACO-MRSA BSI are not well known. Thus, we evaluated clinical and molecular characteristics of MRSA BSI to determine if distinct features are associated with HAHO- or HACO-MRSA strains. Molecular genotyping and medical record reviews were conducted on 282 MRSA BSI isolates from January 2007 to December 2009. MRSA classifications were 38% HAHO-, 54% HACO-, and 8% CA-MRSA. Comparing patients with HAHO-MRSA to those with HACO-MRSA, HAHO-MRSA patients had significantly higher rates of malignancy, surgery, recent invasive devices, and mortality and longer hospital stays. Patients with HACO-MRSA were more likely to have a history of renal failure, hemodialysis, residence in a long-term-care facility, long-term invasive devices, and higher rate of MRSA relapse. Distinct MRSA molecular strain differences also were seen between HAHO-MRSA (60% staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type II [SCCmec II], 30% SCCmec III, and 9% SCCmec IV) and HACO-MRSA (47% SCCmec II, 35% SCCmec III, and 16% SCCmec IV) (P < 0.001). In summary, our study reveals significant clinical and molecular differences between patients with HAHO- and HACO-MRSA BSI. In order to decrease rates of MRSA infection, preventive efforts need to be directed toward patients in the community with health care-associated risk factors in addition to inpatient infection control.

INTRODUCTION

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is an important cause of health care-associated (HA) and community-associated (CA) infection (1). Patients with previous or ongoing health care exposure who develop MRSA infection can be further classified as health care-associated hospital onset (HAHO) or health care-associated community onset (HACO) infections. The HAHO infections develop in the hospital, and the HACO infections develop in the community.

Historically, HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA could be clearly distinguished by clinical characteristics, antibiotic resistance patterns, and molecular typing (2). Well-described HA-MRSA risk factors for infection include a history of hospitalization, intravenous catheters, previous MRSA infections, residence in a long-term-care facility (LTCF), or surgery (3). CA-MRSA strains were detected mostly in younger patients, often associated with skin and soft-tissue infections, and tended to be less resistant to non-β-lactam antibiotics (2). In the United States, the major genotype for HA-MRSA is pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) USA100, clonal complex 5 (CC5), and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type II (SCCmec II), and for CA-MRSA the major genotype is PFGE USA300, CC8, and SCCmec IV (4). Recently, genotyping studies have shown that traditional CA-MRSA strains are increasingly associated with infections in hospitals, and conversely, traditional HA-MRSA strains have been reported in community patients with no HA risk factors (2, 5, 6). Genotyping studies also have shown that certain strains of S. aureus may be more likely to cause invasive infections or bacteremia than colonization (7).

Since 2005, the Emerging Infection Program-Active Bacterial Core surveillance system (EIP-ABCs) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has been tracking MRSA infections in 9 U.S. cities and estimating the national burden of invasive MRSA infections (8, 9). From 2005 to 2011, the total number of MRSA invasive infections has decreased, but the proportion of community onset infections has increased since 2011 (8). Of the estimated 80,461 invasive MRSA infections that occurred in the United States in 2011, 18% were HAHO-MRSA, 60% were HACO-MRSA, and 21% were CA-MRSA (8, 10). MRSA bloodstream infection (BSI) has been the largest category of invasive MRSA disease, comprising 80% of the infections in 2011 (7, 8, 10).

As described above, distinct clinical and molecular differences between HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA BSI have been shown, but very little is known regarding differences between HAHO- and HACO-MRSA BSI. Several important questions arise. Are there distinct clinical features that differentiate between MRSA BSI strains associated with HAHO- and HACO-MRSA cases not previously recognized, and are these clinical traits due to distinct molecular differences between the MRSA strains? In our current study, we attempt to address these questions by characterizing a cohort of MRSA BSI cases by combining traditional clinical and epidemiologic tools with rigorous molecular analysis using several independent methods.

(The manuscript was presented in part at the 49th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Boston, MA, 20–23 October 2011 [11].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, data collection, and definitions.

Retrospective medical record review was conducted on unique patients with MRSA BSI from 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2009 at The Wexner Medical Center of The Ohio State University (OSUWMC). MRSA BSI is defined as any patient with one or more positive MRSA blood cultures. Data collection and genotyping was conducted only on the first isolate. Clinical data collected included demographic information, past medical history, laboratory drug susceptibility data, and HA risk factors in the 12 months preceding the MRSA-positive culture. We also collected data on the presence of any invasive device in the last 7 days preceding the MRSA-positive culture. Outcomes were categorized as cure (complete resolution after antimicrobial drug treatment), failure (persistence of infection and change in antimicrobial drug regimen), relapse/recurrence (redevelopment of MRSA at any site after completion of MRSA treatment), indeterminate (unknown outcome), and death (death due to any cause <30 days after the diagnosis of MRSA BSI or if the patient was never discharged from the hospital). Collected data were entered into a secure database within the OSUWMC Information Warehouse (IW) as previously described (12).

Classification of MRSA infections.

All MRSA BSI cases were classified into three categories: HAHO-, HACO-, and CA-MRSA (9). HAHO-MRSA BSI is defined by positive culture obtained >48 h after admission. HACO-MRSA is defined by positive blood culture obtained <48 h after admission in a patient with one or more HA risk factors as described above. CA-MRSA is defined by positive blood culture obtained <48 h after admission in a patient without HA risk factors.

MRSA isolate testing. (i) Drug susceptibility testing.

The OSUWMC Clinical Microbiology Laboratory identified all MRSA isolates using standard microbiological methods (13). Antimicrobial drug susceptibility testing was performed using the semiautomated MicroScan method (Siemens Diagnostics, Sacramento, CA, USA) using the PROMPT inoculation method. The following drugs and concentrations (μg/ml) were tested: cefazolin (4 to 16), clindamycin (0.5 to 4), daptomycin (0.5 to 4), erythromycin (0.5 to 4), gentamicin (4 to 8), linezolid (1 to 4), oxacillin (0.25 to 2), tetracycline (4 to 8), trimethoprim/SXT (0.5/9.5 to 2/38), and vancomycin (0.25 to 16). For clindamycin, only constitutive testing was performed. A linezolid MIC of >4 mg/liter was confirmed using the Etest method (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), and results were interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (13).

(ii) Genotyping.

All of the MRSA isolates were genotyped by SCCmec typing and repetitive element PCR (rep-PCR). spa typing and PFGE were performed on selected isolates. Testing methods are briefly described below.

(iii) SCCmec typing and mecA confirmation.

The presence of the mecA gene and SCCmec typing was established using a modified multiplex PCR (14). DNA was extracted by heating a bacterial suspension (100 μl) at 95°C for 7 min (15). A PCR mix with a final volume of 25 μl contained 2 μl of DNA template and 12.5 μl of 2× multiplex PCR master mix (Qiagen, Foster City, CA), including HotStartTaq polymerase, 3 mM MgCl2, and deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), was prepared for each isolate. Primer concentrations were doubled from those previously reported to increase the sensitivity of the assay (14). All assays were performed in a gradient thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) using the following conditions: 95°C for 15 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 57°C for 90 s, and 72°C for 90 s; and a final extension of 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were resolved in a 3% Seakem LE (Cambrex) agarose gel with 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (Promega Corporation) at 100 V for 2 h and were visualized with ethidium bromide.

(iv) rep-PCR.

The DiversiLab system (bioMérieux, Durham, NC, USA) is a rapid, standardized, commercially available rep-PCR system for genotyping. rep-PCR analysis was performed in accordance with methods previously described (16). Each new rep-PCR pattern identified was given a sequential numeric identifier to document the specific strain pattern that was unique to our institution. Unlike PFGE, there is no nationally or internationally recognized rep-PCR pattern number for specific MRSA strains. Per the manufacturer's specifications, isolates are designated the same rep-PCR strain pattern if the strains share >95% similarity and are indistinguishable (no band/peak difference) by graph overlay function (17). A cluster is defined as two or more isolates of the same rep-PCR strain pattern.

(v) spa typing.

spa typing (18) was performed by using eGenomics software (www.egenomics.com) as described previously (19). Ridom spa types subsequently were assigned using the spaServer website (www.spaserver.ridom.de). Clonal complex (CC) was inferred from the spa type (19).

(vi) PFGE.

PFGE was performed on at least one representative MRSA isolate from each rep-PCR pattern. The PFGE method used has been described previously (12). PFGE type also was inferred from other isolates in the DiversiLab rep-PCR library, which contains PFGE and SCCmec genotype results for some previously characterized rep-PCR patterns.

Statistical analysis.

All patient demographic, clinical, and molecular typing data were entered in tabular format, and descriptive statistics were generated and analyzed using Minitab Statistical Software, version 16 (Minitab Inc.). Differences among HAHO-, HACO-, and CA-MRSA were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables, analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables, or Kruskal-Wallis test for variables that do not follow a normal distribution. The odds ratio (OR) of death for each one of the risk factors measured here and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated based on binary logistic regression analysis.

Human subject protection.

The study was approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board of the OSU Office of Responsible Research Practices.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

A total of 282 patients with MRSA BSI were identified during the study period: 106 (38%) HAHO-, 153 (54%) HACO-, and 23 (8%) CA-MRSA patients. Clinical characteristics of health care- and community-associated infections are shown in Table 1: 60% (170) of the patients were male, and 73% (206) were white. Patients with HAHO-MRSA had significant history of malignancy, surgery in the past 12 months, invasive devices within 7 days, admission to a surgical service, and longer length of hospital stay. Patients with HACO-MRSA had a higher proportion of renal failure, hemodialysis, residence in an LTCF, invasive devices in the past 12 months, and higher recurrent/relapse of infection and were more likely to be on the medical services (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of patient characteristics between HAHO-MRSA, HACO-MRSA, and CA-MRSA infections

| Parameter | Value for patients infected with: |

P value (HAHO vs HACO) | Value for patients infected with CA-MRSA | P value (between HAHO-, HACO-, and CA-MRSA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAHO-MRSA | HACO-MRSA | ||||

| Total no. of patients | 106 (38) | 153 (54) | 23 (8) | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 0.35 | <0.001 | |||

| Mean (yr) | 59.5 | 57.9 | 43.6 | ||

| Median (yr) | 59.5 | 57 | 42 | ||

| Range (yr) | 19–99 | 19–93 | 20–83 | ||

| 18–24 yr old (no. [%]) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 0.58 | 1(4) | 0.001 |

| 25–44 yr old (no. [%]) | 11 (10) | 22 (14) | 12 (52) | ||

| 45–64 yr old (no. [%]) | 55 (52) | 73 (48) | 8 (35) | ||

| ≥65 yr old (no. [%]) | 39 (37) | 54 (35) | 2 (9) | ||

| Gender (no. [%] male) | 63 (59) | 89 (58) | 0.84 | 18 (78) | 0.18 |

| Race (no. [%] white) | 83 (78) | 105 (69) | 0.09 | 18 (78) | 0.19 |

| Source (no. [%]) | |||||

| Primary bacteremia | 83 (78) | 113 (74) | 0.41 | 10 (43) | 0.003 |

| Past medical history (no. [%]) | |||||

| Diabetes | 31 (29) | 62 (40) | 0.06 | 5 (22) | 0.07 |

| Chronic lung disease | 22 (21) | 39 (25) | 0.38 | 0 (0) | 0.02 |

| Renal failure | 19 (18) | 62 (41) | <0.001 | 1 (4) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 41 (39) | 32 (21) | <0.001 | 2 (9) | <0.001 |

| Healthcare-associated risk factors, past 12 mo (no. [%]) | |||||

| Hospitalization | 64 (60) | 105 (69) | 0.45 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Use of invasive device | 50 (47) | 88 (58) | 0.029 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Surgery | 45 (42) | 43 (28) | 0.017 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Stay in long-term-care facility (LTCF) | 26 (25) | 56 (37) | 0.04 | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| Previous MRSA infection/colonization | 15 (14) | 36 (24) | 0.06 | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 11 (10) | 45 (29) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Other | 11 (10) | 13 (8) | 0.61 | 0 (0) | 0.27 |

| Invasive devices in last 7 days (no. [%]) | |||||

| Central venous catheter/Swan Ganz | 70 (66) | 57 (37) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Foley | 44 (42) | 20 (13) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Ventilation | 32 (30) | 16 (10) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Endotracheal tube | 28 (26) | 10 (6.5) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 16 (15) | 48 (31) | 0.003 | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 15 (14) | 7 (4.6) | 0.007 | 0 (0) | 0.03 |

| Drainage tubes | 13 (12) | 9 (5.9) | 0.07 | 0 (0) | 0.06 |

| Other | 22 (21) | 25 (16) | 0.36 | 1 (4) | 0.16 |

| Outcomes (no. [%]) | 0.003 | 0.003 | |||

| Cure | 51 (48) | 73 (48) | 15 (65) | ||

| Death | 30 (28) | 25 (16) | 0.021 | 1 (4) | 0.009 |

| Failure | 0 (0) | 6 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Indeterminate/null | 20 (19) | 25 (16) | 6 (26) | ||

| Recurrent/relapse | 5 (5) | 24 (16) | 0.006 | 1 (4) | 0.01 |

| Admitting service (no. [%]) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Intensive care unit | 16 (15) | 25 (16) | 2 (9) | ||

| Medical | 45 (42) | 101 (66) | 16 (70) | ||

| Surgical | 39 (37) | 17 (11) | 4 (17) | ||

| Others | 6 (5.7) | 10 (6.5) | 1 (4) | ||

| Length of stay (days) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Mean | 33.2 | 14.6 | 19.7 | ||

| Median | 23.5 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Range | 1–147 | 1–75 | 2–124 | ||

| Disposition (no. [%]) | 0.075 | 0.09 | |||

| Home | 27 (25) | 54 (35) | 10 (43) | ||

| Not applicable or not discharged | 30 (28) | 27 (18) | 2 (8.7) | ||

| Transfer to other facility, LTCF, or rehab center | 49 (46) | 72 (47) | 11 (48) | ||

A total of 56 deaths occurred, yielding an overall case fatality rate of 20% (56/282). The proportion of fatality was significantly higher in patients with HAHO-MRSA (28%; 30/106) than in patients with HACO-MRSA (16%; 25/153) or CA-MRSA (4%; 1/23) (P = 0.009). For the comparison of HA-MRSA risk factors to patient fatality, the presence of invasive devices was significantly associated with an increased odds of death for individuals with HA-MRSA infections (OR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.09 to 3.63) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Evaluation of fatality and health care-associated risk factors in the past 12 monthsa

| Parameter | No. (%) of patients with risk factors | No. (%) of patients who died with risk factor | No. (%) of patients who died without risk factor | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive devices | 138 (49) | 35/138 (25) | 21/144 (15) | 0.025 | 1.99 | 1.09–3.63 |

| Surgery | 88 (31) | 20/88 (23) | 36/194 (19) | 0.42 | 1.29 | 0.70–2.39 |

| Stay in LTCF | 82 (29) | 15/82 (18) | 41/200 (21) | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.45–1.67 |

| Hemodialysis | 56 (20) | 16/56 (29) | 40/226 (18) | 0.071 | 1.86 | 0.95–3.65 |

| Previous MRSA infection/colonization | 51 (18) | 10/51 (20) | 46/231 (20) | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.46–2.10 |

| Other | 25 (9) | 4/25 (16) | 52/257 (20) | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.26–2.42 |

The total number of patients evaluated was 282. A total of 56 patients died.

Drug susceptibility.

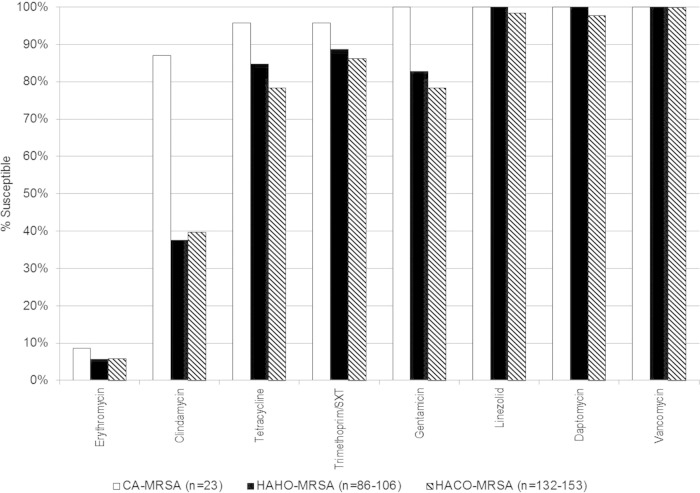

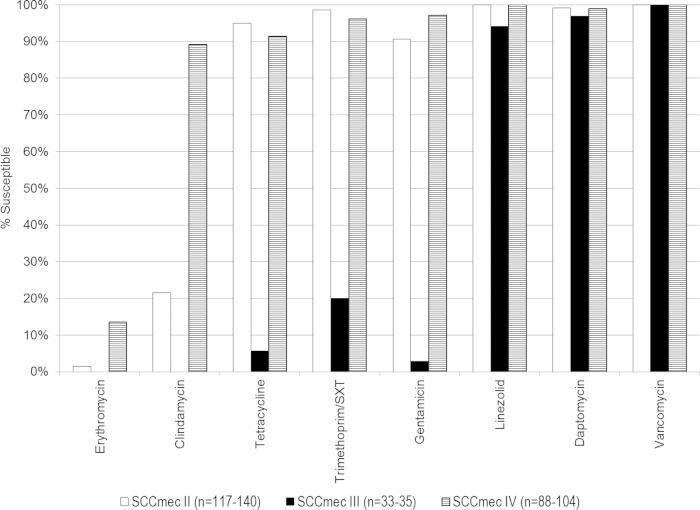

Comparisons of drug susceptibility for HAHO-, HACO-, and CA-MRSA are shown in Fig. 1. All of the isolates were susceptible to vancomycin, with a range from 1 μg/ml to ≤2 μg/ml. Of the 248 isolates tested for linezolid, two were nonsusceptible, with a MIC of >4 mg/liter. Of the 241 isolates tested for daptomycin, two were nonsusceptible, with a MIC of 4 mg/liter, and one was nonsusceptible, with a MIC of 2 mg/liter. MRSA isolates that were not susceptible to linezolid and daptomycin were all in the HACO-MRSA BSI patients (Fig. 1). Comparison of drug susceptibility by SCCmec type is shown in Fig. 2. Increase drug resistance is seen in SCCmec III to all oral antibiotics and gentamicin as previously described (12).

FIG 1.

Comparison of drug resistance for community- and health care-associated MRSA bloodstream infections. The total number (n) of isolates in HAHO-MRSA and HACO-MRSA with drug susceptibility testing varies depending on the specific antibiotic. SXT, sulfamethoxazole.

FIG 2.

Comparison of drug susceptibility by SCCmec typing. The total number (n) of isolates in HAHO-MRSA and HACO-MRSA with drug susceptibility testing varies depending on the specific antibiotic. SXT, sulfamethoxazole.

Molecular typing. (i) SCCmec type.

The 282 isolates were distributed into 5 different SCCmec types: SCCmec II (140; 50%), SCCmec IV (104; 37%), SCCmec III (35; 12%), SCCmec VIII (2; 1%), and SCCmec V (1; <1%). Table 3 shows the clinical characteristics of the subjects stratified by major SCCmec types. The SCCmec type distribution of HAHO-MRSA strains was SCCmec type II (64/106; 60%), SCCmec IV (32/106; 30%), and SCCmec III (10/106; 9.4%). Similarly, the majority of HACO-MRSA strains also were SCCmec II (72/153; 47%), followed by SCCmec IV (53/153; 35%) and SCCmec III (25/153; 16%). All SCCmec III patients had either HAHO- or HACO-MRSA. Among patients with SCCmec type II, significant characteristics included a history of chronic lung disease, hospitalization, invasive devices, surgery, and residence in an LTCF in the past 12 months and recent central catheters. Among patients with SCCmec type III, a higher proportion had HACO-MRSA (25/35; 71%). SCCmec type III patients also had significantly higher proportions of previous hospitalization, invasive devices, previous MRSA infections, and history of parenteral nutrition than patients with SCCmec II or SCCmec IV. Mortality rates were higher for SCCmec II and III, and a higher recurrence/relapse rate was seen for SCCmec III.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of patient characteristics by SCC mec type

| Parameter | Value for patients by SCCmec type |

P value (between SCCmec II and IV) | Value for patients with SCCmec III (n = 35) | P value (between SCCmec II, IV, and III) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II (n = 140) | IV (n = 104) | ||||

| Patient demographics | |||||

| Age | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Mean (yr) | 62 | 50.2 | 58.5 | ||

| Median (yr) | 61.5 | 50.5 | 61 | ||

| Range (yr) | 19–99 | 20–92 | 19–79 | ||

| 18–24 yr old (no. [%]) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (3) | <0.001 | 2 (6) | <0.001 |

| 25–44 yr old (no. [%]) | 13 (9) | 28 (27) | 4 (11) | ||

| 45–64 yr old (no. [%]) | 63 (45) | 57 (55) | 14 (40) | ||

| ≥65 yr old (no. [%]) | 63 (45) | 16 (15) | 15 (43) | ||

| Gender (no. [%] male) | 80 (57) | 62 (60) | 0.7 | 25 (71) | 0.3 |

| Race (no. [%] white) | 107 (76) | 67 (64) | 0.04 | 30 (86) | 0.022 |

| Source (no. [%]) | 0.003 | <0.001 | |||

| Primary bacteremia | 116 (83) | 69 (66) | 19 (54) | ||

| Secondary source | 24 (17) | 35 (34) | 16 (46) | ||

| Classification (no. [%]) | |||||

| HAHO-MRSA | 64 (46) | 32 (31) | <0.001 | 10 (29) | <0.001 |

| HACO-MRSA | 72 (51) | 53 (51) | 25 (71) | ||

| CA-MRSA | 4 (3) | 19 (18) | 0 (0) | ||

| Past medical history (no. [%]) | |||||

| Diabetes | 55 (39) | 31 (30) | 0.013 | 12 (34) | 0.31 |

| Chronic lung disease | 36 (26) | 13 (13) | 0.011 | 10 (29) | 0.023 |

| Renal failure | 46 (33) | 24 (23) | 0.095 | 11 (31) | 0.24 |

| Malignancy | 42 (30) | 26 (25) | 0.43 | 6 (17) | 0.34 |

| HA risk factors, past 12 mo (no. [%]) | |||||

| Hospitalization | 89 (64) | 50 (48) | 0.016 | 28 (80) | 0.002 |

| Use of invasive device | 76 (54) | 41 (39) | 0.022 | 20 (57) | 0.043 |

| Surgery | 57 (41) | 19 (18) | <0.001 | 11 (31) | 0.001 |

| Previous MRSA infection/colonization | 19 (14) | 20 (19) | 0.23 | 12 (34) | 0.017 |

| Stay in LTCF | 58 (41) | 14 (13) | <0.001 | 9 (26) | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 27 (19) | 17 (16) | 0.59 | 10 (29) | 0.24 |

| Other | 7 (5) | 10 (10) | 0.34 | 8 (23) | 0.036 |

| Invasive devices in last 7 days (no. [%]) | |||||

| Hemodialysis | 34 (24) | 17 (16) | 0.15 | 12 (34) | 0.06 |

| Endotracheal tube | 23 (16) | 13 (13) | 0.55 | 2 (6) | 0.29 |

| Ventilation | 31 (22) | 13 (13) | 0.09 | 4 (11) | 0.15 |

| Central venous catheter/Swan Ganz | 80 (57) | 36 (35) | 0.002 | 14 (40) | 0.005 |

| Parenteral nutrition | 13 (9) | 3 (3) | 0.049 | 6 (17) | 0.015 |

| Foley | 35 (25) | 22 (21) | 0.55 | 7 (20) | 0.44 |

| Drainage tubes | 16 (11) | 2 (2) | 0.004 | 4 (11) | 0.005 |

| Other | 20 (14) | 14 (13) | 0.78 | 13 (37) | 0.003 |

| Outcomes (no. [%]) | 0.005 | <0.001 | |||

| Cure | 60 (43) | 67 (64) | 0.001 | 11 (31) | <0.001 |

| Death | 33 (24) | 14 (13) | 0.054 | 8 (23) | 0.014 |

| Failure | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.9) | 0.75 | 2 (6) | 0.24 |

| Indeterminate/null | 34 (24) | 11 (11) | 0.005 | 5 (14) | 0.016 |

| Recurrent/relapse | 11 (7.9) | 10 (10) | 0.6 | 9 (26) | 0.006 |

| Admitting service (no. [%]) | 0.015 | 0.032 | |||

| Intensive care unit | 19 (14) | 16 (15) | 7 (20) | ||

| Medical | 75 (54) | 70 (67) | 15 (43) | ||

| Surgical | 39 (28) | 12 (12) | 9 (26) | ||

| Others | 7 (5) | 6 (6) | 4 (11) | ||

| Length of stay (days) | 0.35 | 0.43 | |||

| Mean | 22.9 | 19.7 | 25.5 | ||

| Median | 14 | 12 | 18 | ||

| Range | 1–132 | 0–147 | 1–100 | ||

| Disposition (no. [%]) | 0.001 | 0.003 | |||

| Home | 33 (24) | 49 (47) | 9 (26) | ||

| Not applicable or not discharged | 34 (24) | 15 (14) | 9 (26) | ||

| Transfer to other facility, LTCF, or rehabilitation center | 73 (52) | 40 (38) | 17 (49) | ||

(ii) rep-PCR and PFGE types.

The isolates were distributed into 52 different rep-PCR patterns, with 91% (258) clustered into 28 distinct rep-PCR patterns (range, 2 to 38 isolates per pattern). Table 4 demonstrates key strain differences for 14 major rep-PCR patterns for MRSA classifications and HA risk factors. Patients with rep-PCR pattern 15 (PFGE 100, SCCmec II) had 100% prior hospitalization and 71% prior surgery. Increased residence in an LTCF was seen commonly in rep-PCR strains 2, 15, 34, 30, and 29 (PFGE100, SCCmec II) and rep-PCR 6 (ST239, SCCmec III). Hemodialysis was more common in rep-PCR patterns 34 (PFGE 100, SCCmec II), 30 (PFGE 100, SCCmec II), and 53 (ST239, SCCmec III).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of rep-PCR pattern, community versus hospital onset, health care-associated risk factors in past 12 months, and outcomes

| PFGE cluster and rep-PCR no. | n | eGenomics spa type (Ridom) | No. (%) of patients with: |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAHO-MRSA | HACO-MRSA | CA-MRSA | Prior hospitalization | History of invasive devices | Prior surgery | Prior MRSA | LTCF | Hemodialysis | Cure | Fatality | |||

| PFGE 100, SCCmec II | |||||||||||||

| 2 | 38 | 2(t002), 11(t105), 23(t548), 693(t1062) | 16 (42) | 19 (50) | 3 (8) | 19 (50) | 24 (63) | 14 (37) | 3 (8) | 16 (42) | 6 (16) | 19 (50) | 12 (32) |

| 15 | 17 | 2(t002), 47(t045), 233(t450) | 8 (47) | 9 (53) | 0 | 17(100) | 8 (47) | 12 (71) | 3 (18) | 8 (47) | 4 (24) | 6 (35) | 4 (24) |

| 66 | 17 | 2(t002), 11(t105), 12(tt062), 24(t242) | 7 (41) | 9 (53) | 1 (6) | 10 (59) | 7 (41) | 6 (35) | 1 (6) | 4 (24) | 1 (6) | 4 (24) | 8 (47) |

| 60 | 13 | 2(t002) | 6 (46) | 7 (54) | 0 | 8 (62) | 5 (39) | 4 (31) | 1 (8) | 6 (46) | 3 (23) | 6 (46) | 1 (8) |

| 34 | 9 | 2(t002), 11(t105), 47(t045) | 4 (44) | 5 (56) | 0 | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | 5 (55) | 1 (11) | 4 (44) | 4 (44) | 4 (44) | 0 |

| 30 | 9 | 2(t002), 268(t067) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | 0 | 3 (33) | 4 (44) | 3 (33) | 0 | 4 (44) | 3 (33) | 3 (33) | 4 (44) |

| 29 | 8 | 2(t002), 11(t105), 1211(t837) | 3 (38) | 5 (63) | 0 | 6 (75) | 5 (63) | 2 (25) | 1 (13) | 4 (50) | 2 (25) | 5 (63) | 0 |

| PFGE ST239, SCCmec III | |||||||||||||

| 6 | 15 | 3(t037) | 3 (20) | 12 (80) | 0 | 13 (87) | 9 (60) | 4 (27) | 6 (40) | 6 (40) | 3 (20) | 8 (53) | 2 (13) |

| 53 | 10 | 3(t037) | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | 0 | 7 (70) | 5 (50) | 4 (40) | 2 (20) | 1 (10) | 4 (40) | 1 (10) | 2 (20) |

| PFGE 300, SCCmec IV | |||||||||||||

| 9 | 33 | 1(t001), 4(t051), 139(t334), 363(t024), 364(t622), 722(t1578) | 11 (33) | 15 (46) | 7 (21) | 19 (58) | 12 (36) | 8 (24) | 5 (15) | 3 (9) | 4 (12) | 20 (61) | 1 (3) |

| 63 | 20 | 1(t001), 46(t190), 68(t451), 245(t121), 364(t622), 664(t197) | 5 (25) | 13 (65) | 2 (10) | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | 3 (15) | 6 (30) | 5 (25) | 3 (15) | 15 (75) | 4 (20) |

| 13 | 10 | 1(t001), 363(t024) | 2 (20) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | 2 (20) | 0 | 0 | 1 (10) | 2 (20) | 7 (70) | 1 (10) |

| 52 | 9 | 1(t001) | 2 (22) | 6 (67) | 1 (11) | 7 (78) | 4 (44) | 2 (22) | 1 (11) | 3 (33) | 2 (22) | 3 (33) | 3 (33) |

| PFGE 800, SCCmec IV | |||||||||||||

| 55 | 9 | 2(t002), 23(t548), 24(t242), 29(t088), 176(t688), 203(t179), 437(tt003), new(new) | 5 (56) | 4 (44) | 0 | 1 (11) | 3 (33) | 2 (22) | 1 (11) | 0 | 0 | 7 (78) | 2 (22) |

A total of 262 isolates were characterized by spa typing. Thirty-four spa types, including 2 new spa types, were identified. spa type 2 (002), which most frequently is associated with HA-MRSA infection, was the most common spa type for both HAHO-MRSA (50/106, 47%) and HACO-MRSA (60/153, 39%). Increased spa type variability was seen in some rep-PCR patterns. Table 5 lists spa types with clusters of three or more isolates per spa type (229 isolates total).

TABLE 5.

Comparison of spa type pattern, community versus hospital onset, health care-associated risk factors in past 12 months, and outcome

| spa type | n | rep-PCR type(s) | PFGE type(s) | No. (%) of patients with: |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAHO-MRSA n (%) | HACO-MRSA | CA-MRSA | Prior hospitalization | History of invasive devices | Prior surgery | Prior MRSA | LTCF | Hemodialysis | Cure | Death | ||||

| 2 | 114 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 15, 16, 21, 28, 29, 30, 34, 36, 37, 45, 47, 50, 55, 60, 66, 81, 82, 90, 96, 99, 104 | 100, 800 | 50 (44) | 60 (53) | 4 (4) | 73 (64) | 62 (54) | 47 (41) | 18 (16) | 45 (39) | 24 (21) | 44 (39) | 29 (25) |

| 1 | 60 | 9, 10, 13, 40, 43, 51, 52, 63, 75, 77 | 300, 500, unknown | 17 (28) | 31 (52) | 12 (20) | 30 (50) | 21 (35) | 9 (15) | 8 (13) | 11 (18) | 10 (17) | 40 (67) | 5 (8) |

| 3 | 34 | 6, 19, 22, 42, 53, 78, 79 | ST239 | 10 (29) | 24 (71) | 0 (0) | 27 (79) | 20 (59) | 10 (29) | 11 (32) | 9 (26) | 10 (29) | 11 (32) | 8 (24) |

| 7 | 4 | 7, 40, 75 | 500, Iberian | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) |

| 11 | 4 | 2, 29, 34, 66 | 100 | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 3 (75) | 2 (50) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 3 (75) | 0 (0) |

| 17 | 4 | 26, 48, 62 | 1000 | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 4 (100) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) |

| 268 | 3 | 30 | 100 | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) |

| 363 | 3 | 9, 13 | 300 | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) |

| 364 | 3 | 9, 63 | 300 | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) |

DISCUSSION

This study adds to our current understanding of the molecular epidemiology of MRSA transmission by demonstrating additional distinctive clinical and molecular differences between HAHO- and HACO-MRSA cases that occur in the hospital and community setting in patients with HA risk factors. Similar to other published results, our study also demonstrated a higher proportion of HACO-MRSA than HAHO-MRSA and CA-MRSA BSI. The HA risk factors identified also were similar to previously published data (7, 20). Patients with HACO-MRSA had a constellation of risk factors (hemodialysis, residence in LTCF, and invasive devices in the past 12 months) which could create a predisposition to MRSA acquisition in a community, albeit health care-associated, environment. HAHO-MRSA patients had characteristics that could predispose them to infections while hospitalized (surgery, recent invasive devices, and longer hospital stays). Although others have indicated community strains have become the predominant strain in their hospital setting (1, 6), the majority of the patients with MRSA BSI in our population had a history of health care exposure with traditional hospital strains.

The data outlined in our study support the premise that there are molecular differences between the strains, beyond risk factors and traditional clinical characterization, that also account for the evolving distribution of hospital and community onset invasive strains. SCCmec typing and phylogenetic analysis have been shown to be better indicators of differentiating between HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA than traditional demographic data and risk factors (21, 22). As expected, SCCmec type IV was highly associated with CA-MRSA BSI in our analysis (Table 3). In this study, the SCCmec type IV isolates also accounted for a large number of HACO- and HAHO-MRSA infections. Similar observations were made by Kuo et al., where patients had SCCmec IV HACO-MRSA infections (20).

We noted the history of invasive device varied from 39% to 57% in SCCmec type comparisons but was 20% to 63% for rep-PCR strain patterns. Studies also have shown that MRSA strains with increased biofilm-forming capacity are seen in patients with invasive lines (23). The analysis of biofilm capacity and the presence of other virulent factors between rep-PCR strains need to be evaluated to determine if they account for the variation in distribution in patients with invasive medical devices.

MRSA BSI in dialysis patients is an important concern, since an estimated 12,823 MRSA BSI occurred among dialysis patients in the United States in 2011 (8, 10, 24). The majority of the hemodialysis patients were community onset with a history of hospitalization in the prior year (24, 25). In a multivariate analysis, chronic renal failure was identified as a significant factor in HACO-MRSA BSI cases (26). Our data also showed that patients with HACO-MRSA had significantly higher incidences of renal failure and hemodialysis. Fortunately, hemodialysis was not a significant factor associated with mortality (P = 0.071; OR, 1.86; CI, 0.95 to 3.65) (Table 2). Molecular strain differences of SCCmec types between HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA have been observed (24, 26). We did not observe differences in hemodialysis patients in SCCmec type comparisons, but there were differences among rep-PCR patterns ranging from 0 to 44%. It is unknown if certain strains are more common in hemodialysis units and lead to HA infections, or if particular strains are more likely to cause skin colonization and predispose the patients who are colonized with a particular strain to develop infection. History of prior colonization and hospitalization are risk factors for the development of invasive MRSA infections (24, 27). There were a total of 56 patients with a history of hemodialysis in the past 12 months. Of these patients, 17 had a history of MRSA infection or colonization; 3/17 were HA-MRSA and 14/17 were HACO-MRSA. Only 19/56 hemodialysis patients had a documented prior MRSA screen in the past 12 months.

The length of stay was significantly longer for HAHO-MRSA and shorter for HACO-MRSA-related BSIs (P < 0.001), but no significant difference was seen in the length of hospitalization by SCCmec type (Tables 1 and 3). It is unknown if patients with HAHO-MRSA were colonized with the MRSA strain prior to their hospitalization, or if MRSA was acquired in the hospital. It has been reported that patients are more likely to develop infection if they are colonized (27), but it also has been shown that despite colonization, some strains may be less likely to cause invasive disease (28).

ST239 MRSA-SCCmec III strain types are common worldwide but are rare in the United States (12). We have recently described an ST239 strain associated with increased mortality and morbidity in Ohio (12). In comparing SCCmec III to SCCmec types II and IV, we found significant differences. Patients with SCCmec III were more likely to have prior colonization and higher rates of prior hospitalization, hemodialysis, and parenteral nutrition. Clinically, these patients had higher recurrence and relapse, which likely contributed to the history of prior hospitalization. Interestingly, none of the SCCmec III patients had CA-MRSA. Therefore, it appears that ST239 (SCCmec type III) is only health care associated.

rep-PCR is a rapid alternative method for sequence typing (17). The rep-PCR method may offer a different stratification than PFGE, SCCmec, and spa types for MRSA classification, HA risk factors, and outcomes (Tables 4 and 5). Interestingly, some rep-PCR patterns in the PFGE100 group appear more like those of community strains (patient characteristics, drug susceptibility testing, and outcome). Some strains, such as rep-PCR strain types 6, 29, 52, and 63 (Table 4), appear to have a higher proportion of HACO-MRSA than other classifications of HAHO-MRSA or CA-MRSA BSIs.

The study is limited due to the geographic location of our patient population. MRSA strains may differ from other institutions in other parts of the United States and globally. Geographically varied rates of S. aureus bacteremia were observed between five academic centers in the United States; however, similar to our study, the overall rates of HACO-MRSA BSI was higher than that for HAHO-MRSA BSI (29). Additional limitations of our study include the lack of biofilm and virulence testing to determine if mortality outcome was influenced by these factors. We also do not know the patients' prior antibiotic usage with respect to drug susceptibility. In addition, patient outcomes were not complete, with indeterminate outcomes due to lack of follow-up information for patients transferred back to their outlying facility or community for local follow-up.

This study does highlight the potential differences between strain types, which may be inherent strain characteristics in addition to health care-associated risk factors that predispose patients to infection. Complete sequence analysis may further define strain characteristics. Additional virulence studies of the strain types also may be able to elucidate key gene combinations that are clinically and phenotypically distinct. Such studies are planned or are under way by our research group.

Conclusion.

The majority of patients with MRSA BSI in our analysis had a history of health care exposure. Significant clinical and molecular differences were seen between patients with HAHO- and HACO-MRSA. In order to decrease rates of MRSA infection, better efforts are needed to identify patients with particular risk factors for developing MRSA BSI. The increased HACO-MRSA invasive infections stresses the importance of preventive efforts directed toward patients in the community with health care-associated risk factors, as well as continued focus on infection control practices in the hospital setting. More discriminatory genotyping and additional virulence studies may assist in identifying strains that may be amenable to targeted infection control and treatment interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the OSU Epicenter Program Team for assistance with data collection; we also thank Jennifer Santangelo, David Newman, and Kelly Kent of the OSU Information Warehouse for assistance with the Web entry portal and data management.

The project described was supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) award number KL2RR025754 (S.-H.W.) from the National Center for Research Resources, funded by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (OD), supported by the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and OSU Marie Davis Bremer award number UL1RR025755 (S.-H.W.). Additional support was provided by the CDC Prevention Epicenters grant 1U01C1000328-01, awarded to K.B.S., S.-H.W., L.H., and P.P.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health. We have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chambers HF. 2001. The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus? Emerg Infect Dis 7:178–182. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naimi TS, LeDell KH, Como-Sabetti K, Borchardt SM, Boxrud DJ, Etienne J, Johnson SK, Vandenesch F, Fridkin S, O'Boyle C, Danila RN, Lynfield R. 2003. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. JAMA 290:2976–2984. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowy FD. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDougal LK, Steward CD, Killgore GE, Chaitram JM, McAllister SK, Tenover FC. 2003. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J Clin Microbiol 41:5113–5120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5113-5120.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez BE, Rueda AM, Shelburne SA, Musher DM III, Hamill RJ, Hulten KG. 2006. Community-associated strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as the cause of healthcare-associated infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 27:1051–1056. doi: 10.1086/507923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Fridkin SK, Reingold A, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Tenover FC. 2006. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and healthcare risk factors. Emerg Infect Dis 12:1991–1993. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler VG Jr, Nelson CL, McIntyre LM, Kreiswirth BN, Monk A, Archer GL, Federspiel J, Naidich S, Remortel B, Rude T, Brown P, Reller LB, Corey GR, Gill SR. 2007. Potential associations between hematogenous complications and bacterial genotype in Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Infect Dis 196:738–747. doi: 10.1086/520088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dantes R, Mu Y, Belflower R, Aragon D, Dumyati G, Harrison LH, Lessa FC, Lynfield R, Nadle J, Petit S, Ray SM, Schaffner W, Townes J, Fridkin S. 2013. National burden of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, United States, 2011. JAMA Intern Med 173:1970–1978. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Zell ER, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Fridkin SK. 2007. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 298:1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kallen AJ, Mu Y, Bulens S, Reingold A, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray SM, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Schaffner W, Patel PR, Fridkin SK. 2010. Health care-associated invasive MRSA infections, 2005-2008. JAMA 304:641–648. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S-H, Khan Y, Mediavilla JR, Hines L, Kreiswirth BN, Pancholi P, Stevenson K. 2011. Comparison of community-onset and healthcare-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus blood stream infections at an academic medical center for 3 years, abstr 31995, poster 1248 49th Annu Meet Infect Dis Soc Am, Boston, MA, 22 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang SH, Khan Y, Hines L, Mediavilla JR, Zhang L, Chen L, Hoet A, Bannerman T, Pancholi P, Robinson DA, Kreiswirth BN, Stevenson KB. 2012. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus sequence type 239-III, Ohio, U S A, 2007-2009. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1557–1565. doi: 10.3201/eid1810.120468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2009. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 19th informational supplement, vol 29, no. 3 M100-S19 CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milheirico C, Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. 2007. Update to the multiplex PCR strategy for assignment of mec element types in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3374–3377. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00275-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilic A, Li H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. 2006. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec types of, as well as Panton-Valentine leukocidin occurrence among, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from children and adults in middle Tennessee. J Clin Microbiol 44:4436–4440. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01546-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healy M, Huong J, Bittner T, Lising M, Frye S, Raza S, Schrock R, Manry J, Renwick A, Nieto R, Woods C, Versalovic J, Lupski JR. 2005. Microbial DNA typing by automated repetitive-sequence-based PCR. J Clin Microbiol 43:199–207. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.199-207.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang SH, Stevenson KB, Hines L, Mediavilla JR, Khan K, Soni R, Dutch W, Brandt E, Bannerman T, Kreiswirth BN, Pancholi P. 2015. Evaluation of repetitive element polymerase chain reaction for surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a large academic medical center and community hospitals. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 8:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shopsin B, Gomez M, Montgomery SO, Smith DH, Waddington M, Dodge DE, Bost DA, Riechman M, Naidich S, Kreiswirth BN. 1999. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol 37:3556–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathema B, Mediavilla J, Kreiswirth BN. 2008. Sequence analysis of the variable number tandem repeat in Staphylococcus aureus protein A gene: spa typing. Methods Mol Biol 431:285–305. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-032-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo SC, Chiang MC, Lee WS, Chen LY, Wu HS, Yu KW, Fung CP, Wang FD. 2012. Comparison of microbiological and clinical characteristics based on SCCmec typing in patients with community-onset meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 39:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kluytmans-Vandenbergh MF, Kluytmans JA. 2006. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: current perspectives. Clin Microbiol Infect 12(Suppl 1):S9–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Hota B. 2008. Are community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains replacing traditional nosocomial MRSA strains? Clin Infect Dis 46:787–794. doi: 10.1086/528716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.del Pozo JL, Patel R. 2007. The challenge of treating biofilm-associated bacterial infections. Clin Pharmacol Ther 82:204–209. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen DB, Lessa FC, Belflower R, Mu Y, Wise M, Nadle J, Bamberg WM, Petit S, Ray SM, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Thompson J, Schaffner W, Pater PR. 2013. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among patients on chronic dialysis in the United States, 2005-2011. Clin Infect Dis 57:1393–1400. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duffy J, Dumyati G, Bulens S, Namburi S, Gellert A, Fridkin SK, Lessa FC. 2013. Community-onset invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections following hospital discharge. Am J Infect Control 41:782–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SC, Lee CW, Shih HJ, Chiou MJ, See LC, Siu LK. 2013. Clinical features and risk factors of mortality for bacteremia due to community-onset healthcare-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 76:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang SS, Hinrichsen VL, Datta R, Spurchise L, Miroshnik I, Nelson K, Platt R. 2011. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection and hospitalization in high-risk patients in the year following detection. PLoS One 6:e24340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calderwood MS, Desjardins CA, Sakoulas G, Nicol R, Dubois A, Delaney ML, Kleinman K, Cosimi LA, Feldgarden M, Onderdonk AB, Birren BW, Platt R, Husang SS. 2014. Staphylococcal enterotoxin P predicts bacteremia in hospitalized patients colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 209:571–577. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.David MZ, Daum RS, Bayer AS, Chambers HF, Fowler VG Jr, Miller LG, Ostrowsky B, Baesa A, Boyle-Vavra S, Fells SJ, Garcia-Houchins S, Gialanella P, Macias-Gil R, Rude TH, Ruffin F, Sieth J, Volinski J, Spellberg B. 2014. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia at Five U.S. academic medical centers, 2008-2011: significant geographic variation in community-onset infections. Clin Infect Dis 59:798–807. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]