Summary

Aging is the greatest risk factor for the development of chronic diseases such as arthritis, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, Alzheimer’s disease, macular degeneration, frailty, and certain forms of cancers. It is widely regarded that chronic inflammation may be a common link in all these age-related diseases. This raises the provocative question, can one alter the course of aging and potentially slow the development of all chronic diseases by manipulating the mechanisms that cause age-related inflammation? Emerging evidence suggests that pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-18 show an age-dependent regulation implicating inflammasome mediated caspase-1 activation in the aging process. The Nod-like receptor (NLR) family of innate immune cell sensors, such as the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin domain-containing-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome controls the caspase-1 activation in myeloid-lineage cells in several organs during aging. The NLRP3 inflammasome is especially relevant to aging as it can get activated in response to structurally diverse damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as extracellular ATP, excess glucose, ceramides, amyloids, urate and cholesterol crystals, all of which increase with age. Interestingly, reduction of NLRP3-mediated inflammation prevents age-related insulin-resistance, bone loss, cognitive decline and frailty. NLRP3 is a major driver of age-related inflammation and therefore dietary or pharmacological approaches to lower aberrant inflammasome activation holds promise in reducing multiple chronic diseases of age and may enhance healthspan.

Keywords: NLRP3, inflammasome, senescence, IL-1, IL-18, cytokines, adipose tissue, macrophage, sarcopenia

Introduction

The number of people living to be 65 years or older is increasing worldwide. Although increased longevity is certainly a great achievement for human health, aging remains the single greatest risk factor for developing chronic disease (Fig. 1). Among the leading causes of death in the elderly are several chronic conditions including heart disease, cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and infection (1). Importantly, many of these diseases are thought to originate from persistent low-grade inflammation (2). Despite this common link between aging, inflammation, and chronic diseases, the biomedical research enterprise currently spends billions of dollars to tackle each of these diseases separately. The economic impact of chronic diseases with increased longevity is huge. An estimated nearly $450 billion dollars were spent on cardiovascular disease alone in the United States in 2010 (3). Medicare spending accounted for 14% of the federal budget in 2011 and this number is expected to increase by 2030 due to the increased number of people living into old age (4). Despite increasing awareness of the health and economic impact of the growing elderly population, limited progress has been made to understand the mechanisms that control age-related inflammation, and causal relationship of these regulators to chronic degenerative diseases is incompletely understood.

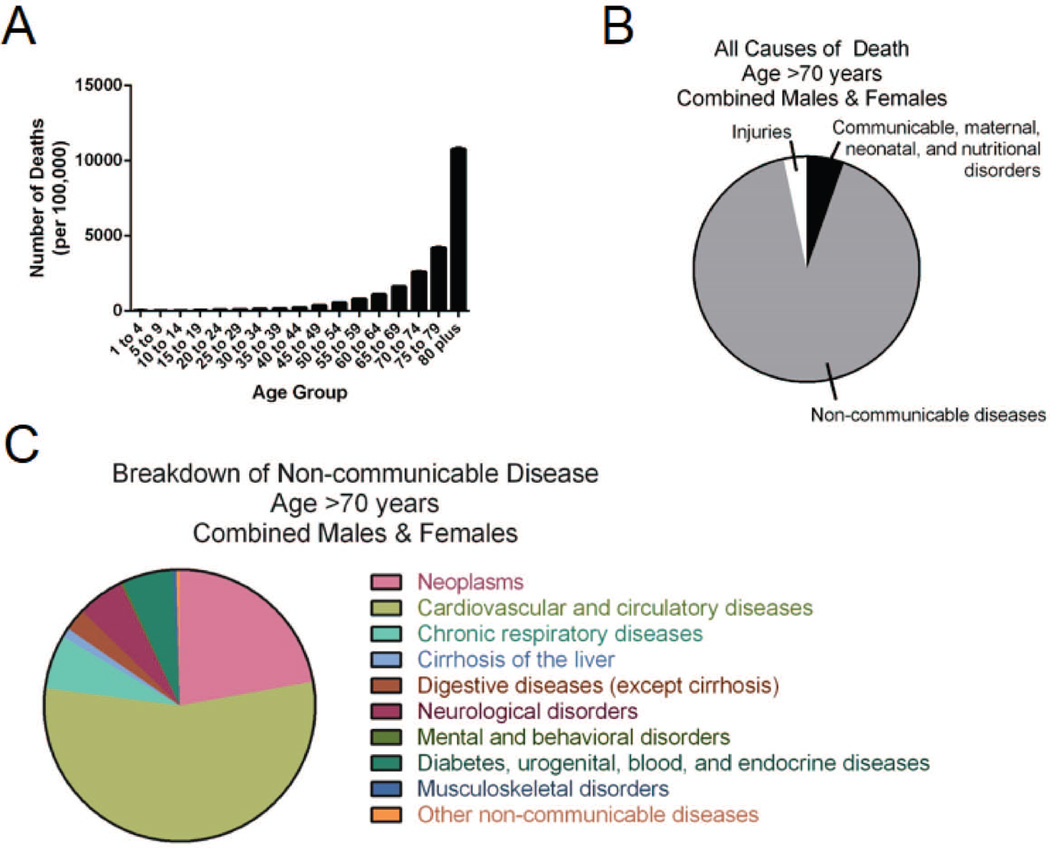

Fig. 1. Aging, disease burden, and mortality statistics.

Incidences and causes of death in the elderly are shown. (A) Numbers of deaths, stratified by age group, in developed countries worldwide. (B) All causes of death in both males and females over age 70 in developed countries. (C) Further breakdown of the non-communicable causes of death in elderly males and females in developed countries. All data was obtained from the Global Health Data Exchange (89).

Just as has been observed in all age groups, the rates of obesity within the aging population are also increasing. About 35% of adults aged 65 and over were obese in 2007–2010, representing over 8 million adults aged 65–74 (5). However, the basic mechanism of how metabolic stress impacts the biology of aging and immune function is not known. As both aging and obesity are known to result in sterile inflammation, the confluence of this increase in ‘gerobesity’ is likely to exacerbate the development of age-related chronic disease and reduce healthspan. Here we discuss the emerging data on cellular and molecular mechanisms of age-related inflammation and how these lead to functional decline and decreased healthspan during aging. We also discuss potential therapeutic interventions to target the triggers of age-related inflammation that may lower disease burden.

Aging, inflammation, and chronic disease

A chronic disease is a state of health where the host cannot maintain homeostasis, and wherein if the triggers of disease are not ameliorated then the individual’s health continues to deteriorate. In contrast, a ‘disorder’ in a host is a state of health where the host is able to maintain homeostasis, but in which the individual’s state of health is less favorable than it would be in the absence of the disorder. Aging is neither considered a disease nor a disorder. Aging is associated with inevitable accumulation of cellular damage as an ‘operational cost’ and exhaustion of endogenous mechanisms to clear the damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). The accumulation of DAMPs such as byproducts of necrotic cells, extracellular ATP, uric acid, amyloid fibrils, and free cholesterol crystals are sensed by the tissue resident innate immune cells like macrophages to trigger chronic low-grade inflammation seen during aging. Tissue-resident phagocytes such as microglia in central nervous system (CNS), Kupffer cells in liver, osteoclasts in bone, or mesangial cells in kidney play important role in maintenance of homeostasis and organ function through production of cytokines for tissue repair and remodeling. Thus, sustained activation of tissue macrophages by aging-associated DAMPs is one of the likely cellular mechanisms of propagation of inflammatory-damage and tissue dysfunction.

The association between aging, increased inflammation, and chronic diseases is now well established. Both men and women over age 65 have increased serum levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), and IL-18 (6, 7). This is important to note because these cytokines have been shown in both mouse and human studies to be associated with age-related diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and frailty (8–10). The increased inflammatory cytokines in the elderly referred to as ‘inflammaging’ is a proposed driver of less successful aging and shortened healthspan (11). Age-related inflammation in multiple organs may lead to functional decline even in the absence of a specific disease. It has been hypothesized that fundamental trade-off between the cost benefit ratio of inflammatory immune response that allows survival against early life infections may have deleterious consequences on organ function as human lifespan extends beyond the reproductive age in a constructed niche of energy excess and relatively low microbial exposure (12). The inflammaging theory posits that ‘aging either physiologically or pathologically can be driven by the proinflammatory cytokines and substances produced by the innate immune system’ (13, 14). If the inflammaging theory is correct, the likely prediction is that an experimental manipulation of a specific innate immune sensing pathway should result in attenuation of age-related functional decline across multiple systems. Although acute inflammation is required for protection against microbial infection, evidence suggests that mechanisms responsible for limiting basal inflammation become dysregulated during aging. This in turn leads to the chronic low-grade inflammation associated with many age-related diseases. Apart from activation of tissue resident macrophages, the tissue leukocyte infiltration has also been shown to be linked with increases in local inflammatory cytokines and disease onset in mouse models of insulin resistance (15, 16).

Aging, innate immune sensors, and inflammasomes

Systemic increases in inflammation is believed to contribute to increased disease prevalence and severity during aging (17). Aging is associated with an increase in IL-18, IL-1β, and IL-6. Importantly, IL-1β and IL-18 are both produced after inflammasome-dependent caspase-1 activation. Intriguingly, many of the endogenous signals that have been identified as inflammasome activators are known to accumulate during aging. Altogether, this suggests that chronic inflammasome activation may significantly contribute to increased inflammation leading to age-related disease. The innate immune system is the first line of defense during microbial infection. However, innate immune cells such as tissue resident macrophages also control local organ function and maintain homeostasis through clearance of cellular debris via phagocytosis and by production of growth factors and cytokines. Macrophages use pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to initiate inflammatory signaling pathways. This process is critical for early control of pathogenic spread. Activation of PRRs leads to assembly of the inflammasome complex. Inflammasomes are comprised of several proteins. First, they contain either a nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat (NLR) protein such as NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRC4, NLRC5, NLRP6, or NLRP7, or they contain a HIN-200 protein like the absent in melanoma (Aim2) inflammasome. NLRs contain pyrin domains (PYD) to enable protein-protein interactions with ASC. Subsequently, ASC binds caspase-1 via caspase-1 activation recruitment domains (CARD). Caspase-1 becomes active after inflammasome assembly and is required for cleavage of the inactive pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active inflammatory forms, IL-1β and IL-18. Complete details of inflammasome activation have been expertly reviewed previously (18).

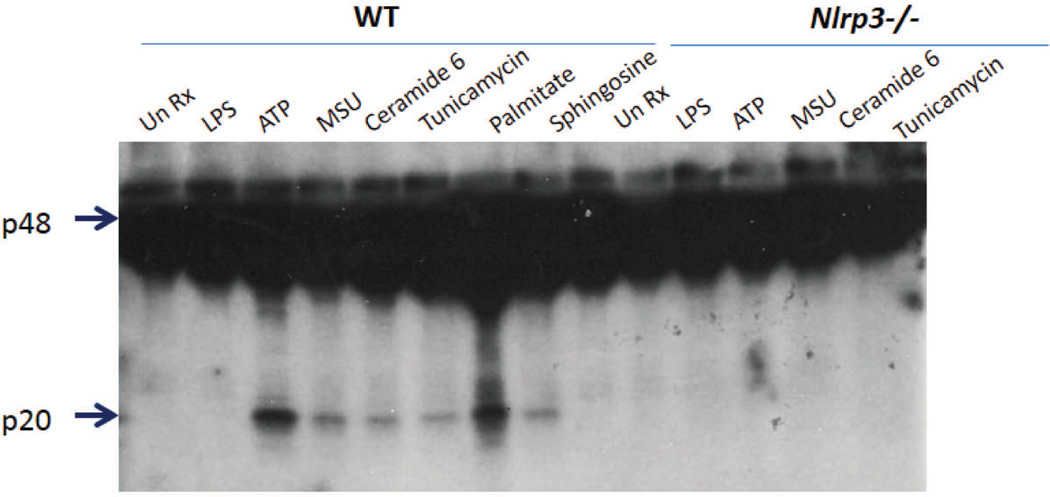

The most well-studied inflammasome complex is the NLRP3 inflammasome due to its broad range of known activators. The NLRP3 inflammasome requires two signals for activation: first, NF-κB-dependent activation of NLRP3 (19) and IL-1β (20), and second, sensing of a danger signal to trigger complex assembly. A variety of danger signals or danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) have been identified as activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome. As briefly mentioned above, many of the DAMPs that activate the inflammasome, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) (21), cholesterol crystals (22), urate crystals (23), and lipotoxic ceramide (24), are endogenous metabolic products known to increase with age. These metabolic activators stimulate caspase-1 cleavage in an NLRP3-dependent mechanism (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Inflammasome activation by metabolic DAMPs is NLRP3-dependent.

Representative Western blot of wildtype and Nlrp3−/− bone marrow-derived macrophages stimulated with LPS + the indicated DAMP. Arrowheads demarcate the p48 pro-caspase-1 and the catalytically cleaved p20 caspase-1 subunit. The p20 subunit of caspase-1 is a marker of activation. All DAMPs shown here are NLRP3-dependent, as no active caspase-1 p20 band is present in the Nlrp3−/− cells.

Inflammasome complexes are primarily expressed in myeloid cells including macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils (25). Many studies have focused on the age-related changes in these cell types with respect to infection. In general, LPS stimulation of macrophages from aged hosts results in lower TNFα and IL-6 secretion compared to adult macrophages (26, 27). While this helps explain why old hosts exhibit poor control of bacterial spread and increased susceptibility to bacterial infections, the production of these cytokines is independent of NLRP3 activation. Although antimicrobial responses by macrophages is an extremely important aspect of their function, it is becoming increasingly clear that sterile inflammation, that is, inflammation generated in the absence of infection, is a more relevant contributor towards age-related inflammation and disease. Additionally, during aging the basal elevation of the NLRP3 inflammasome activity interferes with specific upregulation of caspase-1 that is required for successful immune response against Streptococcus pneumonia infection in old mice, resulting in delayed bacterial clearance (28). This highlights the importance of maintaining proper balance of inflammatory programs during aging for both tissue homeostasis and also host defense during infection. Here we discuss the current knowledge of inflammasome-dependent inflammation during aging and how this might impact health and longevity.

Complement and aging

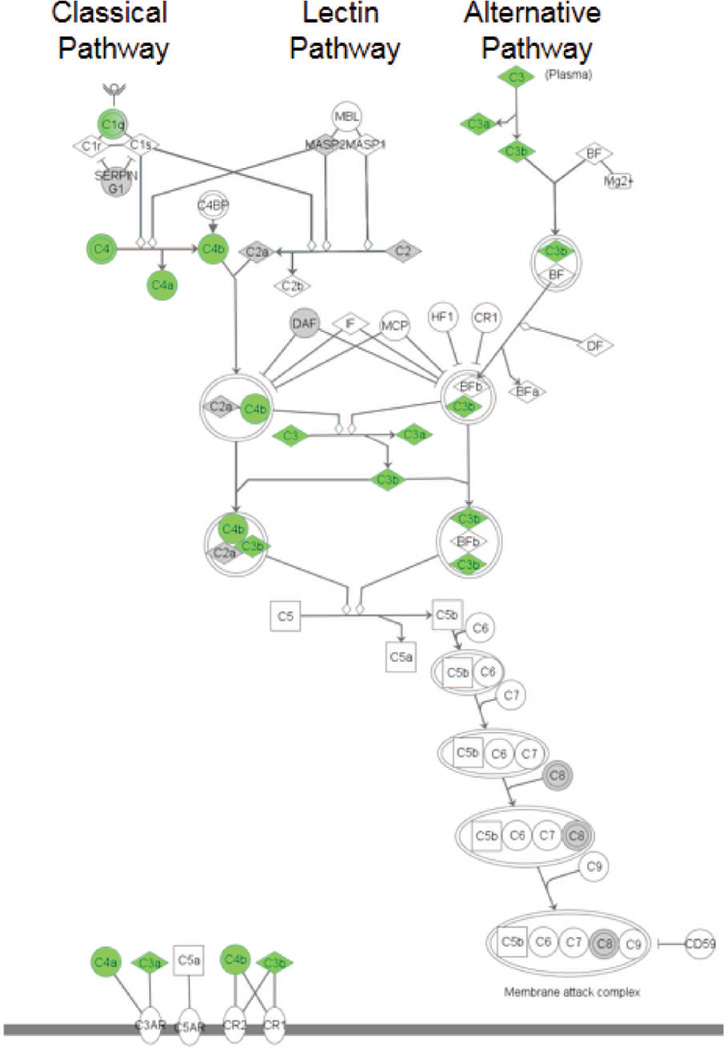

Complement is a pool of soluble proteins that initiates early immune responses against invading pathogens. The complement system contains three major branches: the classical pathway, the alternative pathway, and the lectin pathway. Each of these pathways can be activated by different mechanisms to provide protection against a multitude of pathogens. The classical pathway is triggered by antigen-antibody complexes. The lectin pathway is initiated when plasma proteins, including mannose-binding lectins and ficolins, bind carbohydrates on microbial cell surfaces. Both the classical and the lectin pathways ultimately result in formation of the C4bC2a complex, which can cleave C3 to generate the anaphylatoxins C3a and C3b. The alternative pathway is activated by spontaneous hydrolysis of C3 and remains constitutively active at low levels to allow for rapid responses. Ultimately, C3b gets incorporated into the C5 convertase, which converts C5 into C5a and C5b. C5b can then participate in formation of the membrane attack complex, which is responsible for cell lysis and death of invading pathogens (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Aging-induced increase in complement pathway in hippocampus is regulated by NLRP3.

The basic complement activation cascade is shown. Molecules in green had increased expression (greater than 1.5 fold) in the hippocampus during aging that was prevented in old Nlrp3−/− mice. Results shown are a graphical representation of findings that have been previously published (33).

Complement proteins have previously been shown to play a role in NLRP3 activation. Specifically, C5a, the membrane attack complex, and the C3a receptor were shown to contribute to increased activation of caspase-1 and secretion of IL-1β in vitro (29–31). C5a also promotes monocyte recruitment (32), which may aid in its ability to promote a proinflammatory environment. As macrophages express several complement component receptors, it is conceivable that aberrant signaling through these receptors may contribute to persistent inflammasome activation during aging.

Unbiased global transcriptomic profiling studies revealed increased expression of complement components C3 and C4b in the hippocampus of aged wildtype C57BL/6 mice which was attenuated in age-matched Nlrp3−/− and Il1r−/− mice (33). Interestingly, increased expression of CNS complement components was associated with decreased cognitive function in the aged mice. These findings are in congruence with the observations that mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease exhibit increased caspase-1 and IL1β in the brain, which is discussed in greater detail below (34). More in depth studies are needed to elucidate the direct interactions between complement components and inflammasome activation as a causal mechanism of age-related inflammation. Importantly, as complement proteins are widespread throughout the body, they have the potential to modulate macrophage biology and thus contribute to inflammation in many tissues.

Age-related diseases and inflammation

Macrophages possess both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions and these two opposing roles are carried out by different subsets of macrophages. In the case of tissue injury or microbial infection, circulating monocytes are recruited into tissues where they differentiate into M1 pro-inflammatory macrophages whose main function is to limit the spread of infection. In contrast, M2-like tissue-resident macrophages reside within the tissue, enabling them to respond rapidly, but whose primary function is to maintain tissue homeostasis and resolve inflammation (35). Tissue-resident macrophages, such as microglia are now generally accepted as yolk sac-derived cells that originate independently of adult hematopoiesis that self-renew by local proliferation (36, 37) and are shaped by their local tissue environment (38). The lineage-tracing studies of tissue macrophages in aging and their molecular signatures that may reveal their specific function are currently unknown. However, there is increasing evidence that macrophages are the major responders to sterile ‘danger signals’ in aged tissues and contribute to inflammation that emerges in absence of overt infections. We focus here on tissue-resident macrophages and their potential roles in tissue-specific inflammation and age-related disease.

Thymic involution

Thymic involution is a well-described age-related phenomenon in which the thymic space becomes filled with adipose tissue and lipid-laden cells even in metabolically healthy individuals. The accumulation of lipids in the thymus is associated with decreased production of naïve T cells which is a hallmark feature of immunosenescence. While the exact mechanism of lipid accumulation in the thymus is not known, the presence of excess lipid-derived metabolic intermediates such as ceramides and free cholesterol triggers caspase-1 activation leading to increased IL-1β concentrations and tissue damage. Indeed, thymic myeloid cells have increased caspase-1 activation and IL-1β during aging (39). Furthermore, 23-month-old mice deficient for NLRP3 or ASC were protected from thymic involution, resulting in increased abundance of peripheral naive T cells (33, 39). While thymic myeloid cells have increased caspase-1 activation, thymic epithelial cells express IL-1βR, thus increasing the likelihood of local tissue damage and adverse microenvironment for thymocyte maturation and T-cell export during aging. Proposed mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its relation to thymic atrophy have been thoroughly reviewed (40).

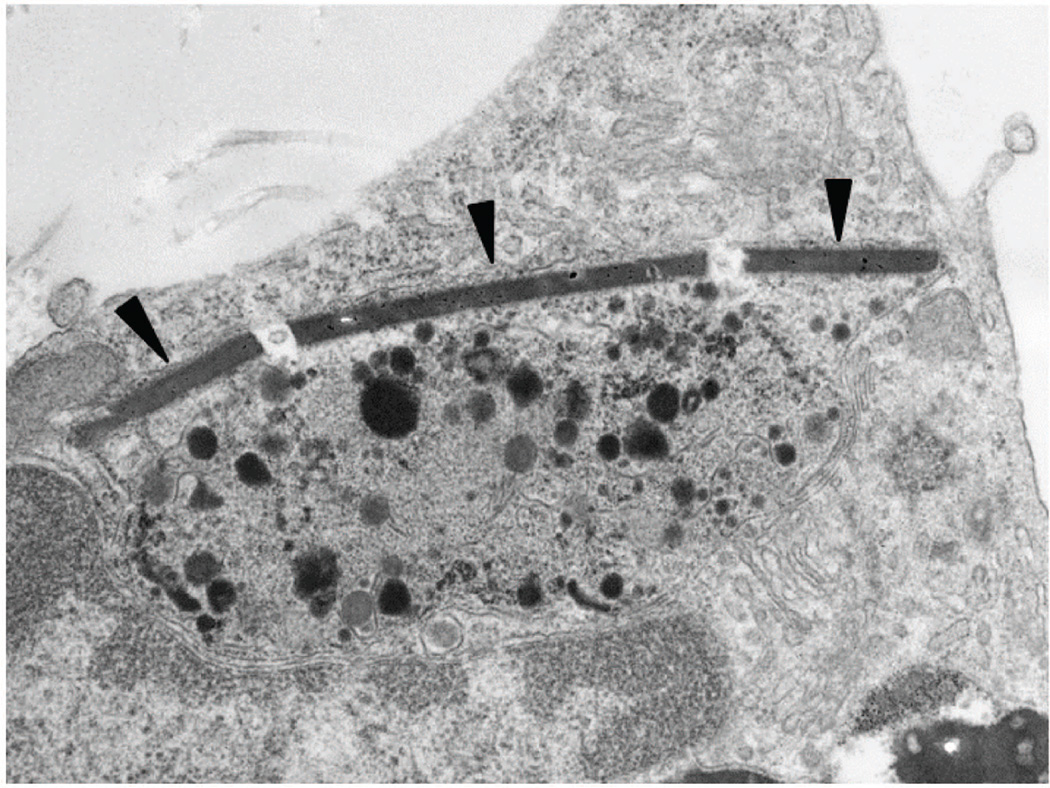

Phenotypic and functional characteristics of tissue-resident thymic macrophages and their role in control of thymic microenvironment with age are not well understood. However, thymic macrophages could be a key players in aging process due to the continuous demand for clearance of apoptotic cell debris in the thymus during the T-cell selection process throughout the lifespan. Apart from thymus, no other tissue, except perhaps the intestine, exhibits this high level of cell turnover, clearance of dead cells, or tissue remodeling. The effect of aging on the thymus and thymic macrophages does not require dietary modification or additional challenge beyond simply aging. The impact of aging on macrophages is evident from the electron microscopy image shown in Fig. 4, in which macrophages isolated from middle aged, but otherwise metabolically healthy mice display several structural anomalies. These studies revealed the presence of crystal structures in macrophages along with increased electron dense material in the lysosomes. Crystal induced complement activation and lysosomal-damage is a known mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and inflammation (41). The presence of crystals in aged tissue macrophages is significant and requires further study to understand the nature and source of this material as endogenous ligands of NLRs or TLRs that can produce age-related chronic inflammation.

Fig. 4. Crystal containing macrophages in aging thymus.

Scanning electron microscopy image of a macrophage isolated from a mouse thymus (12 months old). Arrowheads indicate a crystal structure in the cytoplasm. This cell was not activated or induced in any way, but rather, was isolated from a naturally aged, standard chow-fed C57BL/6 mouse that had been maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility and unmanipulated until the time of sacrifice.

Atherosclerosis

Heart disease, including atherosclerosis, is the leading cause of death in the elderly. Although the importance of macrophages in the progression of disease was well recognized, it was not until 2010 that the NLRP3 inflammasome was shown to play a critical role in initiation of atherosclerosis in mice (22). Patients with atherosclerosis had elevated aortic NLRP3 expression that correlated with coronary severity (42) and peripheral blood monocytes from patients with coronary artery disease had increased expression of NLRP3, caspase-1, and IL-1β (43). Cholesterol crystals in plaques are one of the important activators of NLRP3 inflammasome and ablation of NLRP3 in mice protects against atherosclerosis (22). Unfortunately, because C57BL/6 mice do not spontaneously develop atherosclerosis, the complete dependence of disease initiation in relation to aging has not been tested and an aging mouse model of atherosclerosis has not yet been established. However, as the role of the inflammasome has been shown to be critical in the hematopoietic cell compartment using bone marrow transfers into irradiated atherosclerosis-susceptible mouse strains (22), it stands to reason that this would hold true under normal aging conditions.

CNS inflammation and cognitive decline

Age-related decline in memory and cognition is a major contributor to reduced healthspan. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia and its single greatest risk factor is age (44). As people continue to live longer, the number of people with AD continues to increase as well. One of the classical features of AD is the presence of amyloid-β plaques, due either to overproduction or decreased degradation of amyloid-β proteins. Importantly, amyloid-β proteins can be potent activators of the innate immune system (45) and specifically the NLRP3 inflammasome in microglia (46). Microglia are the resident macrophages of the central nervous system. It is believed that they may play both a protective role as well as a contributory role in the development of neuroinflammation. Although originally thought to be able to clear amyloid-β plaques, an AD mouse model deficient for microglia have equal plaque formation in their brain compared to untreated mice (47). Although the exact mechanism of increased neuroinflammation in AD is not known, it is becoming increasingly apparent that microglia inflammasome activation may be an important critical factor. Similar to AD patients, the APP/PS1 mouse model of AD exhibits increased active caspase-1 and IL-1β in the brain compared to wildtype mice. Importantly, ablation of NLRP3 or Caspase1 in this mouse model protected mice from neuroinflammation and cognitive decline (34). Consistent with these studies, aged Nlrp3−/− mice were protected from age-related increase in astrogliosis, microglia activation and elevation of IL-1 and TNF in the CNS. In addition, aging-associated increase in interferon response in hippocampus and complement activation was reduced in mice deficient in NLRP3 as well as mice deficient in inflammasome adapter proteins ASC or PYCARD (33). Importantly, aged Nlrp3−/− mice displayed improved cognitive ability, which was measured by stoneT maze tests and rotating rod tests (33). Taken together, the NLRP3 inflammasome significantly contributes to neuroinflammation, ultimately contributing to significant cognitive decline during aging.

Metabolic disease/T2D

Aging is associated with major changes in body composition such as loss of muscle mass, reduction in subcutaneous adipose tissue and increase in visceral fat and lipid accumulation in liver. Thus even in elderly with normal BMI, aging is associated with increase in visceral adiposity often described as sarcopenic obesity: the paradoxical change of increased adiposity despite reduced BMI. While this fat redistribution may result in apparent weight loss, increased visceral fat is a primary risk factor for many metabolic and inflammatory diseases. Thus, it is likely that increases in lipotoxic fatty acids derived from dysfunctional visceral adipose tissue in elderly with normal bodyweight contributes to chronic inflammation which is associated with insulin-resistance and increased mortality (48).

The association of obesity and T2D is well established. With regard to aging, this is particularly important because the prevalence of obesity and metabolic disease are increasing in the elderly. Data from the 2011–2012 NHANES study estimated that greater than 30% of both males and females over age 60 were overweight, defined by BMI > 30 (49). Obesity can also accelerate age-associated phenotypes and is an additional risk factor for age-related diseases, including immune senescence (50), osteoporosis (51), and frailty (52). Excess adipose tissue, and in particular visceral adipose tissue, is believed to be the source of many inflammatory mediators in obesity. The influx of both innate and adaptive immune cells into adipose tissue during obesity and how this contributes to local inflammation has become a major area of interest during the past few years (53–55).

It is now appreciated that macrophages exist in healthy visceral adipose tissue with an anti-inflammatory M2-like phenotype. However, during obesity, the prevalence of classically activated, inflammatory M1-like macrophages increases. Incidentally, aging adipose tissue is also described to contain increased M1-like macrophages, in the absence of high fat diet feeding (56). M1 macrophages are credited with the increased TNFα, IL-6, and IL1-β typically observed in obese patients and mouse models. However, what signals specifically recruit these cells to adipose tissue and what triggers their activation is not entirely known. Importantly, Nlrp3−/− mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) were resistant to diet-induced activation of caspase-1 and subsequent IL-1β production, resulting in improved glycemia compared to wildtype mice fed HFD (24). Similarly, HFD-induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation to cause pancreatic islet inflammation, leading to loss of beta cells, insulin production and development of T2D (57). Interestingly, unlike aged Nlrp3−/− mice, Il1r−/− animals fed a normal chow diet were not protected from age-related glucose intolerance (33), suggesting multiple or divergent roles for NLRP3 and IL-1 actions on metabolic homeostasis. Consistent with this possibility, caspase-1 has been shown to unexpectedly target and degrade glycolysis pathway enzymes during activation (58). As the abundance of visceral fat tissue increases during aging, this is likely to be a major source of inflammation in the elderly.

Much more is known about fat tissue dysfunction in obesity than is known about adipose tissue dysfunction in aging. Senescent cells, believed to arise as a means to prevent malignant spread of tumor cells, are described to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to increased inflammation and tissue damage (59). In a progeroid mouse model of greatly accelerated aging, removal of senescent cells in vivo delayed the aging phenotype in these mice (60). It has been proposed that senescent cells in adipose tissue may contribute to age-related inflammation. However, it is not clear what specific event(s) initiates the differentiation of adipocytes to become senescent adipocytes. Furthermore, given there are no clear surface markers to identify senescent cells in vivo the relative abundance of senescent-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) cells or their contribution to adipose tissue inflammation is unknown (61). Future studies to identify the origin of adipose tissue in inflammation in aging may reveal mechanisms that give rise to insulin-resistance and T2D.

Osteoporosis and frailty

Osteoporosis is a condition in which decreased bone strength results in increased bone fracture and is a common malady in the elderly (61). Frailty is a syndrome that afflicts a subset of the elderly population and is described as a state of hyperinflammation that accelerates functional decline (62). Osteoporosis rates are exceptionally high in frail individuals (63). Decreased bone strength during aging can result from (i) excessive bone resorption or (ii) insufficient bone formation after resorption (64). Normal bone health is maintained by balancing bone breakdown and new bone regeneration. These tasks are performed by bone resident macrophages: osteoclasts and osteoblasts, responsible for resorption and building, respectively. During aging adipose tissue can also get redistributed to bones and we have shown that bone marrow of aged mice contains increased numbers of large adipocytes (50). Increased adipose tissue in bone can disrupt bone architecture, weakening the bone and potentially increasing the risk of fracture and osteoporosis. Although hormonal and nutritional influences on bone are well described, the potential role of inflammation in bone homeostasis is considerably less understood. Patients with chronic activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome due to missense mutations have high incidence of osteoporosis (17/20 patients that ranged from age 3–28 years old) (65). Similarly, a mouse neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID) model exhibits reduced bone mass measured by decreased trabecular bone volume and decreased cortical area and thickness due to increased bone resorption (66). Accordingly, compared to aged WT animals, the 24-month-old Nlrp3−/− mice show increased bone mineral content as well as increased bone mineral density and cortical and trabecular thickness (33). Interestingly, increased cortical bone thickness is associated with longer lifespan in mice (67). Aged Nlrp3−/− mice also performed better in rotating rod tests and treadmill tests, suggesting improvements in functional measures of frailty. This highlights the importance of NLRP3 driven inflammation in regulating age-related osteoporosis.

Potential mechanisms of age-related inflammasome activation

It is clear that age-associated diseases affect a variety of tissues. As we have highlighted above, many age-related conditions appear to be regulated, in part, by the NLRP3 inflammasome. As already stated, many of the DAMPs known to activate the inflammasome increase with age. However, the question still remains: what changes during aging predispose the host to increased inflammasome activation? In this regard, two mechanisms may be relevant to age-related inflammation: (i) mitochondrial dysfunction leading to oxidative stress, which is known to contribute to inflammasome activation and also increases with age, and (ii) autophagy, which limits inflammasome activation and decreases with age.

There are many sources of reactive oxygen species in the cell, including NADPH oxidase and respiring mitochondria. Both of these ROS sources have been shown to be differently associated with regulation of inflammasome activation. The specific source of ROS that leads to inflammasome activation is not clear at this time. Several groups have reported seemingly contrasting results for different requirements of NADPH oxidase or mitochondrial respiration for ROS-dependent inflammasome activation (21, 68). Interestingly, ROS are proposed to be a major determinant of aging (70). Therefore, increased ROS in the aged host could lead to aberrant inflammasome activation, thus causing chronic low-grade inflammation.

Autophagy is a cellular recycling process in which organelles or proteins are degraded in an autolysosome and the components are redistributed within the cell. Autophagy is thought to be induced during periods of stress, for example during calorie restriction, to maintain energy balance and reduce cellular energy expenditure (69). In addition to autophagy induction during times of cell stress, autophagy is also maintained at basal levels in the cell. This basal level of autophagy is likely to be important for cell homeostasis during aging and sterile inflammation. Indeed, inhibition of autophagy leads to increased inflammasome activation (68, 70) and cells deficient for autophagy proteins exhibit inflammasome hyperactivation (71). During aging there is a loss of proteostasis that is thought to contribute to age-related disease. This is thought to be due, in part, to decreased autophagy during aging (72). Depressed autophagy during aging would result in the intracellular accumulation of damaged proteins and organelles, which could lead to inflammasome activation in aged cells.

Intervention for inhibiting the aberrant NLRP3 inflammasome activation

While genetic models have been critical tools for elucidating the mechanism of NLRP3 inflammasome in age-related inflammation, the pharmacological or dietary approaches to deactivate the inflammasome are necessary for translation of the basic findings. Interestingly, several dietary interventions have shown robust inflammasome inhibition in mice that maybe applicable to humans. These include ketogenic diet (73), addition of ω-3 fatty acids (74), and caloric restriction (24). In concordance with the proposed relationship between decreased inflammasome activity and improved healthspan, both ketones (75) and calorie restriction (76) have been reported to extend lifespan in animal models.

Dietary interventions

Ketogenic diet

Ketone bodies, β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), and acetoacetate support mammalian survival during periods of starvation by serving as a source of ATP in the TCA cycle. BHB is a major ketone metabolite that is produced from fatty acid oxidation once liver glycogen stores get depleted. BHB levels are therefore increased by caloric restriction, high-intensity exercise or adherence to a low carbohydrate ketogenic diet (73). Many studies have tested the potential role for ketones to reduce inflammation (77, 78). Recent studies have tested the hypothesis that if macrophages are exposed to alternate metabolic fuel such as BHB instead of glucose, whether this can impact the mechanisms that regulate inflammation. Interestingly, BHB can inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages in both mouse and human cells (73). Mechanistically, the inhibitory effects of BHB upon inflammasome activation are at 2 levels (73). First, K+ efflux, known to be a critical step for inflammasome activation (79), was blocked by BHB. Second, BHB also blocked ASC oligomerization, suggesting BHB blocked assembly of the inflammasome complex (80). It remains to be tested whether ketogenic diets that elevate BHB levels will prove to be effective against age-related chronic diseases driven by the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

Several studies have tested whether the anti-inflammatory properties of ω-3 fatty acids may be mediated by reduced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Indeed, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) was shown to decrease IL-1β secretion in macrophages and monocytes after NLRP3 activation (74, 81, 82). Each of these studies identified separate mechanisms that mediated this action: blocking signaling of G protein-coupled receptors (74), blocking TLR1/2 dimerization and subsequently MyD88 recruitment to lipid rafts following TLR stimulation (81), and blocking NF-κB translocation and promoting autophagy (82). Of interest, the study by Snodgrass et al. (81) also showed that saturated fatty acids can activate peripheral human monocyte NLRP3 without the requirement for a second DAMP signal. Taken together, these studies suggest that ω-3 fatty acids may be able to block either signal 1 or signal 2, in a cell type-specific manner, to block inflammasome activation.

Calorie restriction

Calorie restriction (CR), without malnutrition, is the established non pharmaceutical intervention that extends healthspan and lifespan. The aged mice undergoing chronic CR, which will elevate metabolites such as BHB, have reduced NLRP3 activation in their adipose tissue and NLRP3 activity is also reduced in overweight humans after weight loss induced by CR (24). CR also protects against lipid accumulation in the aging thymus, resulting in preservation of thymic integrity and the peripheral T-cell pool in old mice (50). As lipotoxic lipids such as ceramides and palmitate cause inflammasome activation during aging, this may be one of the potential mechanisms of reduced inflammasome activity in aged CR animals. Indeed, in an investigation of the aging serum metabolome in mice, CR was shown to preserve some lipid metabolites known to be altered during aging (83). The salutary effect of CR on healthspan maybe mediated in part by decreasing ROS and elevated autophagy, which may also block NLRP3-mediated inflammation in aging. The effects of CR in humans as an anti-inflammatory intervention are so far not established. Importantly, a recent randomized controlled multi-center study called the Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy (CALERIE) is complete (84). This unique randomized controlled study, CALERIE is poised to generate a great deal of new insight into the feasibility and the potential mechanism of caloric restriction on inflammation in humans. Previous CR studies included human cohorts undergoing voluntary calorie restriction without specific researcher intervention or dietary specifications (85). While these were critical first steps that show reduction in inflammatory markers upon CR in humans, more controlled studies are expected to definitively describe the impact of CR on human physiology

Small molecules

The possibility of using small molecules to block inflammasome activation remains an attractive goal to decrease chronic inflammation. Inflammasome inhibitors could have major health impacts, just as NSAIDs have had significant health impacts for decreasing inflammation via COX inhibition. However, this therapeutic potential must be explored cautiously. While the reduction of chronic inflammation may promote increased healthspan, it cannot be ignored that the inflammasome plays a critical role in host protection during microbial infection. Although this latter function has not been the focus of this review, it should not be understated. This will likely require careful timing and dosage of inflammasome inhibitors to promote healthspan or longevity without compromising the already waning immune function in the elderly. Perhaps partial inhibition rather than complete blockade of NLRP3 activation would be sufficient to prevent age-related inflammatory diseases. However, this remains a completely open research area. At this time, no such studies have undertaken the task of testing long-term inflammasome inhibition on lifespan or healthspan.

Conclusions

Significant progress has been made elucidating the role of the inflammasome in age-related disease and functional decline. It is clear that aging, independent of additional external challenge or induction, leads to NLRP3 inflammasome activation in multiple tissues, ultimately increasing local inflammation and causing dysfunction (Fig. 5). However, it is not entirely clear what endogenous signals promote inflammasome activation and subsequent sterile inflammation. Studies in germ-free mice suggest that LPS, a common model for NLRP3 activation, is probably not the only candidate for inflammasome priming ligands in vivo (86). Additional research will be required to identify other potential endogenous ligands capable of providing the priming signal required for inflammasome activation. It will be interesting to see what endogenous ligands can provide this signal and if tissue-specific expression changes susceptibility of developing certain chronic diseases.

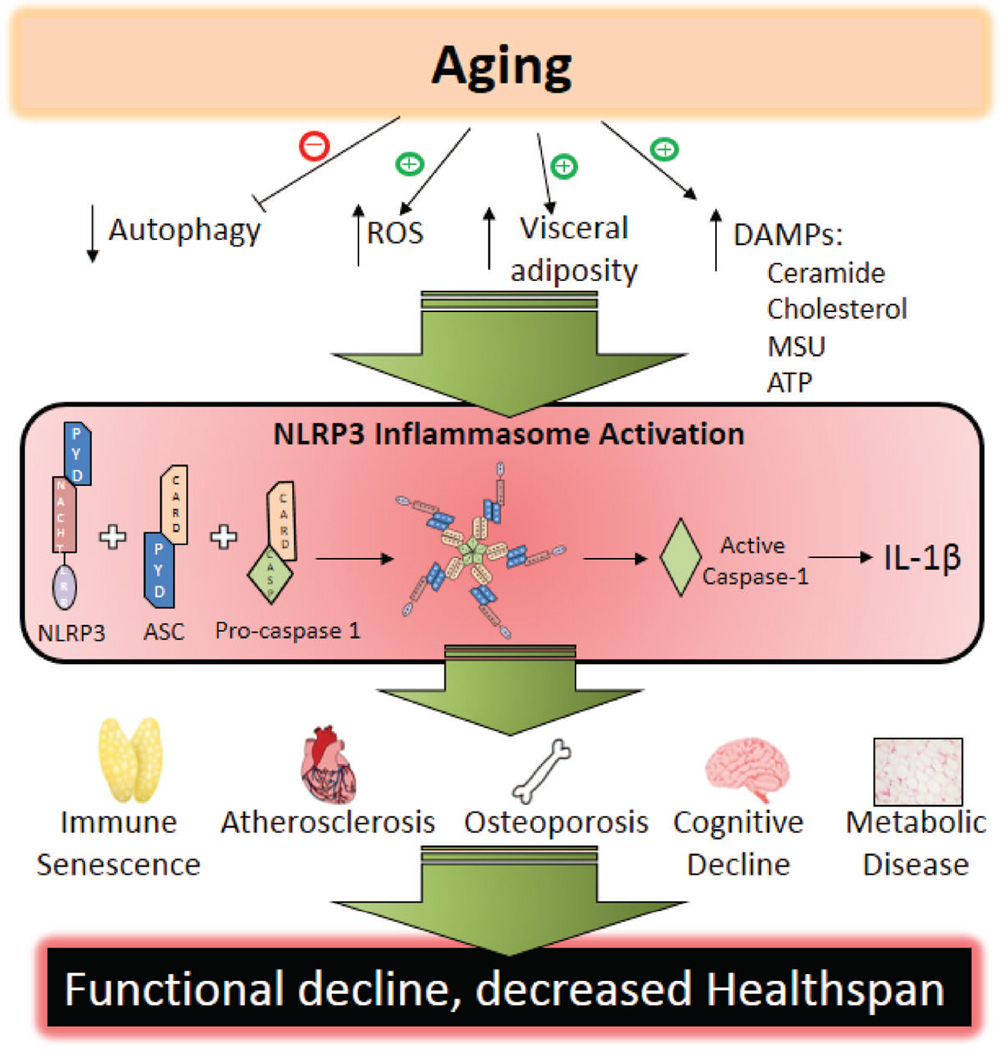

Fig. 5. Proposed mechanism of age-related inflammasome activation.

Schematic representing a proposed mechanism of inflammasome activation during aging and how this leads to increases in chronic diseases.

In addition to endogenous ligands of inflammasome activation, tissue and cellular sources of inflammation remain a critical part of understanding mechanisms driving age-related diseases. Here we have broadly discussed the central role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in mediating many diseases during aging and have described this under the assumption that tissue-resident macrophages are an important factor. Furthering these studies with tissue-specific and cell-type specific deletions would more conclusively identify sources of inflammation. Of particular interest is adipose tissue. Obesity accelerates aging phenotypes (87) and is known to increase leukocyte infiltration in adipose tissue to cause inflammation. This, coupled with the relative increase in visceral adiposity in the elderly, reinforces the importance of adipose tissue as immunologically active organ during aging (88). However, we know very little about the biology of aging adipose tissue. This is likely to be a major source of inflammation and should become a top priority for the inflammation and aging researchers.

Identifying inflammasome inhibitors that limit functional decline without compromising the antimicrobial functions of the inflammasome remains a challenge for aging research. Interventions that successfully achieve both of these features have the greatest likelihood of extending healthspan rather than simply chronological lifespan. After all, the primary goals of aging research is to improve the quality of life during aging and to enhance healthy aging. The ability of dietary interventions to attenuate inflammasome activation is exciting because these can be quickly tested in humans. In retrospect, it should not be surprising that dietary modulation can have such a strong impact upon inflammasome activation, as many of the known NLRP3 activators are metabolic byproducts (Fig. 2). Regardless, it remains to be seen whether similar treatments in humans confer comparable benefits as in mice. Overall, it is clear that persistent inflammation is a key driver of age-related disease and that down regulation of aberrant NLRP3 inflammasome activation may reduce the onset or severity of multiple age-related chronic diseases.

Acknowledgements

Research in Dixit lab is supported in part by NIH grants AI105097, AG043608, DK090556 and AG045712.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.NIA. Global Health and Aging. http://wwwnianihgov/sites/default/files/global_health_and_agingpdf.2011.

- 2.Pawelec G, Goldeck D, Derhovanessian E. Inflammation, ageing and chronic disease. Current opinion in immunology. 2014;29:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Hear Disease and Stroke Prevention. Addressing the Nation's Leading Killers: At a Glance 2011. http://wwwcdcgov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/AAG/dhdsphtm.2011.

- 4.Medicare spending and financing fact sheet. Kaiser Family Foundation Web site http://kfforg/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-spending-and-financing-fact-sheet/.2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fakhouri TH, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among older adults in the United States, 2007–2010. NCHS data brief, no 106.2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen M, et al. Circulating levels of TNF-alpha and IL-6-relation to truncal fat mass and muscle mass in healthy elderly individuals and in patients with type-2 diabetes. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2003;124:495–502. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrucci L, et al. The origins of age-related proinflammatory state. Blood. 2005;105:2294–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinarello CA. Interleukin 1 and interleukin 18 as mediators of inflammation and the aging process. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006;83:447S–455S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.447S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruunsgaard H, Pedersen BK. Age-related inflammatory cytokines and disease. Immunology and allergy clinics of North America. 2003;23:15–39. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8561(02)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leng S, Chaves P, Koenig K, Walston J. Serum interleukin-6 and hemoglobin as physiological correlates in the geriatric syndrome of frailty: a pilot study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:1268–1271. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franceschi C, et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2007;128:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okin D, Medzhitov R. Evolution of inflammatory diseases. Current biology : CB. 2012;22:R733–R740. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franceschi C, et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2000;908:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goto M. Inflammaging (inflammation + aging): A driving force for human aging based on an evolutionarily antagonistic pleiotropy theory? Bioscience trends. 2008;2:218–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu H, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagareddy PR, et al. Adipose tissue macrophages promote myelopoiesis and monocytosis in obesity. Cell metabolism. 2014;19:821–835. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen H, Miao EA, Ting JP. Mechanisms of NOD-like receptor-associated inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2013;39:432–441. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauernfeind FG, et al. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:787–791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barker BR, Taxman DJ, Ting JP. Cross-regulation between the IL-1beta/IL-18 processing inflammasome and other inflammatory cytokines. Current opinion in immunology. 2011;23:591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duewell P, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vandanmagsar B, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011;17:179–188. doi: 10.1038/nm.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guarda G, et al. Differential expression of NLRP3 among hematopoietic cells. Journal of immunology. 2011;186:2529–2534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehmer ED, Goral J, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Age-dependent decrease in Toll-like receptor 4-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production and mitogen-activated protein kinase expression. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:342–349. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0803389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renshaw M, Rockwell J, Engleman C, Gewirtz A, Katz J, Sambhara S. Cutting edge: impaired Toll-like receptor expression and function in aging. Journal of immunology. 2002;169:4697–4701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krone CL, Trzcinski K, Zborowski T, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. Impaired innate mucosal immunity in aged mice permits prolonged Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization. Infection and immunity. 2013;81:4615–4625. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00618-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An LL, et al. Complement C5a potentiates uric acid crystal-induced IL-1beta production. Eur J Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/eji.201444560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asgari E, et al. C3a modulates IL-1beta secretion in human monocytes by regulating ATP efflux and subsequent NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Blood. 2013;122:3473–3481. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-502229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laudisi F, et al. Cutting edge: the NLRP3 inflammasome links complement-mediated inflammation and IL-1beta release. Journal of immunology. 2013;191:1006–1010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Youm YH, et al. Canonical Nlrp3 inflammasome links systemic low-grade inflammation to functional decline in aging. Cell metabolism. 2013;18:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heneka MT, et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer's disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature. 2013;493:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature11729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nature immunology. 2013;14:986–995. doi: 10.1038/ni.2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto D, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz C, et al. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavin Y, et al. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell. 2014;159:1312–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Youm YH, et al. The Nlrp3 inflammasome promotes age-related thymic demise and immunosenescence. Cell Rep. 2012;1:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dixit VD. Impact of immune-metabolic interactions on age-related thymic demise and T cell senescence. Semin Immunol. 2012;24:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samstad EO, et al. Cholesterol crystals induce complement-dependent inflammasome activation and cytokine release. Journal of immunology. 2014;192:2837–2845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng F, Xing S, Gong Z, Xing Q. NLRP3 inflammasomes show high expression in aorta of patients with atherosclerosis. Heart, lung & circulation. 2013;22:746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang L, Qu P, Zhao J, Chang Y. NLRP3 and downstream cytokine expression elevated in the monocytes of patients with coronary artery disease. Archives of medical science : AMS. 2014;10:791–800. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.44871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evans DA, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in a community population of older persons. Higher than previously reported. Jama. 1989;262:2551–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bianca VD, Dusi S, Bianchini E, Dal Pra I, Rossi F. beta-amyloid activates the O-2 forming NADPH oxidase in microglia, monocytes, and neutrophils. A possible inflammatory mechanism of neuronal damage in Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:15493–15499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halle A, et al. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nature immunology. 2008;9:857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grathwohl SA, et al. Formation and maintenance of Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid plaques in the absence of microglia. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1361–1363. doi: 10.1038/nn.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fontana L, et al. Identification of a metabolic signature for multidimensional impairment and mortality risk in hospitalized older patients. Aging cell. 2013;12:459–466. doi: 10.1111/acel.12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. Jama. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang H, Youm YH, Dixit VD. Inhibition of thymic adipogenesis by caloric restriction is coupled with reduction in age-related thymic involution. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:3040–3052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosen CJ, Bouxsein ML. Mechanisms of disease: is osteoporosis the obesity of bone? Nature clinical practice Rheumatology. 2006;2:35–43. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blaum CS, Xue QL, Michelon E, Semba RD, Fried LP. The association between obesity and the frailty syndrome in older women: the Women's Health and Aging Studies. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:927–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feuerer M, et al. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med. 2009;15:930–939. doi: 10.1038/nm.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishimura S, et al. CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nat Med. 2009;15:914–920. doi: 10.1038/nm.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winer S, et al. Normalization of obesity-associated insulin resistance through immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2009;15:921–929. doi: 10.1038/nm.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lumeng CN, et al. Aging is associated with an increase in T cells and inflammatory macrophages in visceral adipose tissue. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:6208–6216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Youm YH, Adijiang A, Vandanmagsar B, Burk D, Ravussin A, Dixit VD. Elimination of the NLRP3-ASC inflammasome protects against chronic obesity-induced pancreatic damage. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4039–4045. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shao W, Yeretssian G, Doiron K, Hussain SN, Saleh M. The caspase-1 digestome identifies the glycolysis pathway as a target during infection and septic shock. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:36321–36329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tchkonia T, et al. Fat tissue, aging, and cellular senescence. Aging cell. 2010;9:667–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baker DJ, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riggs BL, et al. Changes in bone mineral density of the proximal femur and spine with aging. Differences between the postmenopausal and senile osteoporosis syndromes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1982;70:716–723. doi: 10.1172/JCI110667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mohler MJ, Fain MJ, Wertheimer AM, Najafi B, Nikolich-Zugich J. The Frailty syndrome: clinical measurements and basic underpinnings in humans and animals. Experimental gerontology. 2014;54:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colon-Emeric CS. Recent advances: osteoporosis in the "oldest old". Current osteoporosis reports. 2013;11:270–275. doi: 10.1007/s11914-013-0158-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raisz LG. Pathogenesis of osteoporosis: concepts, conflicts, and prospects. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:3318–3325. doi: 10.1172/JCI27071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hill SC, Namde M, Dwyer A, Poznanski A, Canna S, Goldbach-Mansky R. Arthropathy of neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID/CINCA) Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bonar SL, et al. Constitutively activated NLRP3 inflammasome causes inflammation and abnormal skeletal development in mice. PloS one. 2012;7:e35979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller RA, Kreider J, Galecki A, Goldstein SA. Preservation of femoral bone thickness in middle age predicts survival in genetically heterogeneous mice. Aging cell. 2011;10:383–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marino G, Pietrocola F, Madeo F, Kroemer G. Caloric restriction mimetics: natural/physiological pharmacological autophagy inducers. Autophagy. 2014;10:1879–1882. doi: 10.4161/auto.36413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shi CS, et al. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1beta production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nature immunology. 2012;13:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shin JN, Fattah EA, Bhattacharya A, Ko S, Eissa NT. Inflammasome activation by altered proteostasis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:35886–35895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.514919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vilchez D, Saez I, Dillin A. The role of protein clearance mechanisms in organismal ageing and age-related diseases. Nature communications. 2014;5:5659. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Youm YH, et al. Ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nature Medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nm.3804. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yan Y, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids prevent inflammation and metabolic disorder through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2013;38:1154–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Edwards C, Canfield J, Copes N, Rehan M, Lipps D, Bradshaw PC. D-beta-hydroxybutyrate extends lifespan in C. elegans. Aging (Albany NY) 2014;6:621–644. doi: 10.18632/aging.100683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Masoro EJ. Subfield history: caloric restriction, slowing aging, and extending life. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2003;2003:RE2. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2003.8.re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masino SA, Ruskin DN. Ketogenic diets and pain. Journal of child neurology. 2013;28:993–1001. doi: 10.1177/0883073813487595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shimazu T, et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by beta-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 2013;339:211–214. doi: 10.1126/science.1227166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Munoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martinez-Colon G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Nunez G. K(+) efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38:1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu A, et al. Unified polymerization mechanism for the assembly of ASC-dependent inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;156:1193–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Snodgrass RG, Huang S, Choi IW, Rutledge JC, Hwang DH. Inflammasome-mediated secretion of IL-1beta in human monocytes through TLR2 activation; modulation by dietary fatty acids. Journal of immunology. 2013;191:4337–4347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Williams-Bey Y, et al. Omega-3 free fatty acids suppress macrophage inflammasome activation by inhibiting NF-kappaB activation and enhancing autophagy. PloS one. 2014;9:e97957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.De Guzman JM, et al. Chronic caloric restriction partially protects against age-related alteration in serum metabolome. Age. 2013;35:1091–1104. doi: 10.1007/s11357-012-9430-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rochon J, et al. Design and conduct of the CALERIE study: comprehensive assessment of the long-term effects of reducing intake of energy. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2011;66:97–108. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fontana L, Meyer TE, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Long-term calorie restriction is highly effective in reducing the risk for atherosclerosis in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:6659–6663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wright SD, et al. Infectious agents are not necessary for murine atherogenesis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;191:1437–1442. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang H, et al. Obesity accelerates thymic aging. Blood. 2009;114:3803–3812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Grant RW, Dixit VD. Adipose tissue as an immunological organ. Obesity. 2015 doi: 10.1002/oby.21003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Institute for Health Metrics and Evalulation. 2013 [Google Scholar]