Abstract

Fibrosis is a frequent, life-threatening complication of most chronic liver diseases. Despite major achievements in the understanding of its pathogenesis, the translation of this knowledge into clinical practice is still limited. In particular, non-invasive and reliable (serum-) biomarkers indicating the activity of fibrogenesis are scarce. Class I biomarkers are defined as serum components having a direct relation to the mechanism of fibrogenesis, either as secreted matrix-related components of activated hepatic stellate cells and fibroblasts or as mediators of extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis or turnover. They reflect primarily the activity of the fibrogenic process. Many of them, however, proved to be disappointing with regard to sensitivity and speci-ficity. Up to now hyaluronan turned out to be the relative best type I serum marker. Class II biomarkers comprise in general rather simple standard laboratory tests, which are grouped into panels. They fulfil most criteria for detection and staging of fibrosis and to a lesser extent grading of fibrogenic activity. More than 20 scores are currently available, among which Fibrotest™ is the most popular one. However, the diagnostic use of many of these scores is still limited and standardization of the assays is only partially realized. Combining of panel markers in sequential algorithms might increase their diagnostic validity. The translation of genetic pre-disposition biomarkers into clinical practice has not yet started, but some polymorphisms indicate a link to progression and outcome of fibrogenesis. Parallel to serum markers non-invasive physical techniques, for example, transient elastography, are developed, which can be combined with serum tests and profiling of serum proteins and glycans.

Keywords: liver fibrosis, liver fibrogenesis, biomarkers, serum markers, genetic biomarkers, fibrosis scores, hepatic stellate cells, TGF-β

Introduction

The ultimate goals of biomedical research are focused on the translation of new pathogenetic insights to clinical practice. As examples improved diagnosis and follow-up, more efficient and specific therapeutic modalities, and identification of (genetic) risk factors or precipitating mechanisms for a given clinical condition are important clinical requirements and, thus, challenges for translational research. These efforts are clearly visible in the current research on cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis in the liver and other organ fibrosis as well, which has brought over the last 20 years or so a plenitude of new insights into (i) the composition of the fibrotic extracellular matrix (ECM), (ii) cellular sources of ECM, (iii) the nature of the molecular mediators regulating ECM expression, ECM turnover and paracrine cellular interactions, (iv) resolution of ECM, apoptosis of contributing cells (hepatic stellate cells [HSC], hepatocytes) and reversibility of fibrosis. Goals are to find therapeutic options, at least experimentally, and to establish innovative non-invasive biomarkers indicating the activity (progression) of development (fibrogenesis) rather than the stage (extent) of fibrotic organ transition [1, 2].

However, up to now, actual clinical handling of liver fibrotic patients did not profit so much from biomedical fibrosis research. Ongoing clinical trials, however, are promising that therapeutic breakthroughs and improvements of diagnosis can be expected in the near future [3].

Therapeutic trials need frequent, reliable, objective and cost-effective diagnostic and follow-up procedures, which complement liver biopsies as ‘surrogate markers’. Besides invasiveness (mortality rate 1:103 to 1:104, severe complications in 0.57% of cases) and the likelihood of sampling error [1/50 000th (about 30 mg) of the liver mass (∼ 1500 g) can hardly be representative for the whole organ] of biopsy histological examination depends on sample quality, that is, on length and size of the tissue specimen (co-efficient of variation between 45 and 55%, accuracy 65–75%) [4] and on the subjective evaluation of morphological changes (‘observer error’) including grading of necro-inflammatory activity (the driving force of fibrogenesis) and staging (extent) of fibrotic organ transition [5, 6]. Thus, the diagnostic value of the biopsy as ‘gold standard’ in the detection of fibrosis/fibrogenesis must be questioned. This situation strengthens the need for harmless, alternative or complementary serum biomarkers. Since they derive in part from patho-genetic pathways, a brief overview on fibrogenesis facilitates their understanding.

Pathways, cells and molecular mediators in liver fibrogenesis

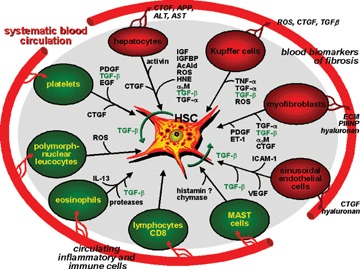

Current knowledge ascribes liver-specific pericytes, that is, HSC, a major role in ECM production and re-modelling [7–10]. HSC, formerly termed vitamin A-storing cells, fat-storing cells, lipocytes or Ito-cells are located in the sub-endothelial space of Disse in close proximity to hepatocytes embracing with starlike extensions (spines) the sinusoidal endothelial tube [11]. They express some heterogeneity and represent about 15% of total resident liver cells and about 30% of non-parenchymal cells including Kupffer cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells and pit cells [12]. The ultra-structural features are characterized by large triacylglycerol-filled vacuoles containing retinoids [11, 13]. Besides their function as major vitamin A storage sites [14], that is, around 85% of liver vitamin A is located in this cell type, HSC were recently identified as antigen-presenting cells (APC) [15, 16] and are likely to have additional functions in liver cell renewal, regeneration, immunoregulation, angiogenesis and vascular re-modelling [17]. Their dominant role in fibrogenesis is based on their ability to change the phenotype from retinoid-storing, resting cells to contractile, smooth-muscle α-actin positive, vitamin A-depleted myofibroblasts (MFB) with a strongly developed endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi-apparatus if HSC are challenged by necro-inflammatory stimuli [1, 18]. Myofibroblasts synthesize and secrete virtually all of the matrix components found in ECM of the fibrotic liver (Fig. 1). This, however, does not rule out the contribution of other cell types and mechanisms to enhance matrix production in chronically inflamed liver tissue. The role of portal (MFB), in particular in biliary fibrosis, has been emphasized [19, 20] and, recently, the influx on bone-marrow-derived fibrocytes [21]via the circulation into the damaged tissue has been shown [22–24] Similarly, circulating monocytes, monocyte-like and mesenchymal stem cells have the potential to change to fibroblasts and other cell types if the appropriate microenvironment is provided [25]. Furthermore, actual research is focused on the possibility of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [26], which describes the transition of biliary epithe-lial cells or even of hepatocytes to fibroblasts, which participate actively in the generation of fibrotic ECM. However, the role of EMT in liver fibrogenesis is still under debate, but is well established in lung and kidney fibrosis [26].

1.

Schematic presentation of the pathogenetic sequence of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis based on the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSC) and transdifferentiation to matrix-synthesizing myofibroblasts (MFB). The inset of the electron micrograph shows retinoid-filled lipid droplets of HSC indenting the nucleus. Surrogate pathogenetic mechanisms contributing to the expansion of the myofibroblast pool in fibrotic liver are indicated: epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (EMT) of biliary epithelial cells or even hepatocytes, transformation of circulating monocytes at the site of injury to fibroblasts and the influx of bone marrow-derived fibrocytes into damaged tissue. Examples of serum biomarkers reflecting the pathogenetic sequence are given, but a considerable overlap is noticeable. Abbreviations: see Table 2, CRP, C-reactive protein; CSF, colony-stimulating factor; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; GLDH, glutamate-dehydrogenase; PIVKA, prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence

The molecular mediators of the complex cellular network between stellate cells, resident liver cells, platelets and invaded inflammatory cells are mostly known (Fig. 2). The fibrogenic master cytokine is transforming growth factor (TGF)-β[10, 27] followed by platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), endothelin-1, angiotensin II and certain fibroblast growth factors, but also non-peptide signalling components, such as acetalde-hyde (in alcoholic fibrosis) and reactive oxygen species and H2O2 are noteworthy [11]. The bioactive, 25 kD TGF-β homodimer not only activates HSC, but stimulates ECM synthesis in HSC/MFB and fibrob-lasts/fibrocytes. Furthermore, TGF-β is a driving cytokine of EMT, stimulates chemokine (receptor) expression, apoptosis of hepatocytes (a pre-requisite for fibrogenesis) and decreases ECM catabolism by down-regulation of matrix metallo-proteinases (MMPs) and up-regulation of tissue inhibitor of met-alloproteinase (TIMPs), the specific tissue inhibitors of MMPs [28]. Several other functions of TGF-β are known including a strong immunosuppressive effect, mitogenic or anti-proliferative actions (depending on the cell type), regulation of cell differentiation and tumour suppression in the early stage. Thus, there is a need to regulate the activity of TGF-β sensitively by extracellular proteolytic activation of a large molecular weight precursor (large latent TGF-β complex). The latent TGF-β complex is the primary secretion product of TGF-β, which can be covalently fixed in the fibrotic ECM by a transglutaminase-dependent reaction. Bioactive TGF-β is released by proteolytic truncation of the complex. Furthermore, bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7), a member of the TGF-β gene superfamily, is a potent antagonist of TGF-β, for example, an inhibitor of TGF-β-driven EMT and apoptosis [26, 29]. BMP-7 reverses TGF-β signalling, which occurs via phosphorylated Smad proteins transferring the signal from the serine-threonine-kinase receptors to the Smad-binding elements in the promoter region of TGF-β target genes. One of these TGF-β-dependent genes is that of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2), a cysteine-rich, secreted, 38 kD multi-domain protein, which has an important role as a downstream modulator of TGF-β effects [30, 31]. CTGF synthesis is not limited to HSC and (MFB). Instead, TGF-β-dependent CTGF gene expression and secretion was recently shown to occur in hepato-cytes in culture and in experimental liver fibrosis [32]. Additional antagonists of TGF-β are synthetic and naturally occurring PPAR-γ agonists like prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2), thiazolidone and triterpenoids [33]. These chemicals might gain therapeutic application in human fibrosis. Due to its multiple functions TGF-β is termed ‘plasticity-factor’, notifying its extensive cross-talk with other cytokines and signalling pathways, for example, p38 MAP kinases, ERK and JNK.

2.

Network of resident liver cells (red) and inflammatory non-liver resident cells (black) with hepatic stellate cells in the process of activation and transdifferentiation to myofibroblasts. Major molecular mediators are indicated. The influx of inflammatory and immune competent cells from the circulation into the damaged liver tissue is illustrated. Secreted products of resident liver cells leading to biochemical changes in blood of liver fibrotic patients are exemplified. Abbreviations: AcAld, acetalde-hyde; α2M, α2-macroglobulin; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; EGF, epidermal growth factor; ET-1, endothelin-1; HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; HSC, hepatic stellate cells; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IGFBP, IGF-binding proteins; ROS, reactive oxygen species; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Classification of biomarkers of fibrosis

Serum- or plasma-based biomarkers of liver fibrogenesis/fibrosis can be sub-divided in two classes: Class I fibrosis biomarkers are pathophysiologically derived from ECM turnover and/or from changes of the fibrogenic cell types in liver described above. They should reflect the activity of the fibrogenic and/or fibrolytic process and, thus, re-modelling of ECM. These biomarkers do not indicate the extent of connective tissue deposition, that is, the stage of fibrotic transition of the organ. Frequently, they are costly laboratory tests and are the result of translation of fibrogenic mechanisms into clinical application. Thus, their selection is hypothesis-driven. In contrast, class II fibrosis markers have been statistically proven (multi-variate analyses) to be best correlated with fibrosis and to a lesser extent with fibrogenesis or fibrolysis. Class II markers mostly estimate the degree of fibrosis (extent of ECM deposition). In general, they comprise common clinical-chemical tests (enzymes, proteins, coagulation factors), which do not necessarily reflect ECM metabolism or fibro-genic cell changes. Their pathobiochemical connection with fibrogenesis is indirect if at all. Thus, their selection is not hypothesis-driven, but empiric. The markers are standard laboratory tests and are integrated into multi-parametric panels.

In general, both types of serum biomarkers follow different pathophysiological concepts with diverse clinical implications. Class I markers inform about ‘what is going on’ (grade of fibrogenic activity), class II markers indicate ‘where fibrosis is’ (stage of fibrosis).

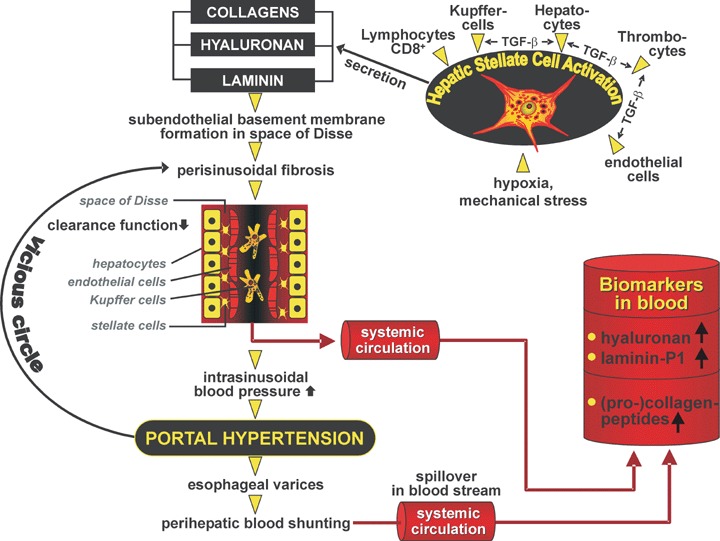

Class I biomarkers of fibrosis

This group of fibrogenic biomarkers comprises mainly secretion products of activated HSC and portal (MFB), i.e., matrix components, ECM-related enzymes, TGF-β-dependent export proteins of hepatocytes and mediators of ECM-synthesis or turnover (Table 1). The elevation of these components in the circulation is due to increased expression of ECM-components in the fibrotic tissue (e.g. by HSC) and fractional spillover into the systemic bloodstream. Additionally, reduced clearance by Kupffer cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells or hepatocytes, for example, by perihepatic blood shunting or decrease of scavenger receptor functions of the respective cell types contributes to their elevation in blood (Fig. 3). Some of the previously recommended enzymes of collagen metabolism (e.g. prolylhydroxylase, lysyloxidase, -hydroxylase, collagen peptidase) have nowadays only anecdotic character because their activities in serum do not reflect reliably matrix synthesis, but cell necrosis (Table 1). In addition, their measurement is laborious and costly involving radio-enzymatic, mostly not standardized, cumbersome assays [34]. Similarly, catabolic enzymes of the glycoprotein and proteogly-can metabolism, such as -glucuronidase and N-acetyl- -D-glucosaminidase have not convinced as biomarkers of liver fibrosis. Summarizing the plenitude of existing literature, only a few class I fibrosis biomarkers have reached a certain clinical importance [35–37]. In several studies, hyaluronan (formerly termed hyaluronic acid) currently proves to be the relative best class I biomarker of fibrosis having sensitivities and specificities of 86–100% and 88%, respectively, if cirrhosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [38] and other etiologies are considered [39]. The diagnostic power of hyaluronan is based on the high negative predictive value (98–100%) at a cut-off concentration of 60 μg/l, which is significantly higher than the positive predictive value of 61%. Promising diagnostic sensitivity and negative predictive value can be ascribed to the stimulated synthesis of hyaluronan in activated HSC [40], its direct secretion into the sinusoidal bloodstream, and the short half-lifetime of 2–9 min in the circulation, which is prolonged in disease conditions by a reduced clearance in the sinusoidal endothelial cells [41]. Of the several pro-collagen and collagen fragments proposed as biomarkers [35] only the aminoterminal propeptide of type III pro-collagen (PIIINP) has reached a limited, but no widespread and continuous clinical application [42]. Reported sensitivities and specificities vary considerably around 76–78% and 71–81%, respectively, which can be increased if combined with additional collagen fragment markers. It should be noticed that PII-INP, hyaluronan and several other class I fibrosis markers are not disease-specific, because elevations are also reported for rheumatoid diseases, chronic pancreatitis, lung fibrosis, scleroderma and others. A series of other studies was focused on the clinical significance of the elevated P1-fragment of the large molecular weight basement membrane glycoprotein laminin [43]. It was reported to be a predictor of portal hypertension, because a positive correlation was noticed between the portal venous pressure and the increase of the P1-laminin fragment in blood [44]. Positive and negative predictive values are given with 0.77 and 0.85, respectively, sensitivity and specificity with 87% and 74%, respectively [44]. If combined with hyaluronan [45] or aminoterminal pro-peptide of type III pro-collagen [46], the diagnostic criteria for assessing portal hypertension can be further improved.

1.

Class I biomarkers of liver fibrogenesis

| Extracellular matrix-related enzymes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Specimen | Method | ||||||

| Serum | Urine | biopsy Liver | ||||||

| Prolylhydroxylase | + | - | + | Radio-enzymatic, RIA | ||||

| Monoamine-oxidase | + | - | (+) | Enzymatic | ||||

| Lysyloxidase | + | - | + | RIA | ||||

| Lysylhydroxylase | + | - | - | RIA | ||||

| Galactosylhydroxylysyl-glucosyltransferase | + | - | + | RIA | ||||

| Collagenpeptidase | + | - | + | Enzymatic | ||||

| N-Acetyl- β-D-glucosaminidase | + | + | + | Enzymatic | ||||

| Collagen fragments and split products | ||||||||

| Type of collagen | Specimen | Method | ||||||

| Serum | Urine | Liverbiopsy | ||||||

| Type I pro-collagen | ||||||||

| • N-terminal pro-peptide (PINP) | + | - | + | ELISA | ||||

| • C-terminal pro-peptide (PICP) | + | - | + | RIA | ||||

| Type III pro-collagen | ||||||||

| • Intact pro-collagen | + | - | - | RIA | ||||

| • N-terminal pro-petide (PIIINP) | ||||||||

| • Complete pro-peptide (Col 1–3) | + | - | - | RIA | ||||

| • Globular domain of pro-peptide (Col-1) | + | - | - | RIA | ||||

| Type IV collagen | ||||||||

| • NC1-fragment (C-terminal cross-linking domain [PIVP]) | + | + | - | ELISA, RIA | ||||

| • 7S domain (‘7S Collagen’) | + | + | - | RIA | ||||

| Type VI-Collagen | + | + | + | RIA | ||||

| Glycoproteins and matrix-metalloproteinase (inhibitors) | ||||||||

| Marker | Specimen | Method | ||||||

| Serum | Urine | Liver tissue | ||||||

| Laminin, P1-fragment | + | - | - | RIA, EIA | ||||

| Undulin | + | - | - | EIA | ||||

| Vitronectin | + | - | - | EIA | ||||

| Tenascin | + | - | - | ELISA | ||||

| YKL-40 | + | - | + | RIA/ELISA | ||||

| (Pro)matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-2) | + | - | - | ELISA | ||||

| Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP-1, TIMP-2) | + | - | - | ELISA | ||||

| sICAM-1 (soluble intercellular adhesion molecule, sCD54) | ||||||||

| sVCAM-1 (soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule, sCD106) | + | - | - | ELISA | ||||

| Glycosaminoglycans | ||||||||

| Marker | Specimen | Method | ||||||

| Serum | Urine | Liver tissue | ||||||

| Hyaluronic acid (Hyaluronan) | + | - | - | Radioligand assay ELISA | ||||

| Molecular mediators | ||||||||

| Marker | Specimen | Method | ||||||

| Serum | Urine | Liver tissue | ||||||

| Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) | + | - | + | ELISA | ||||

| Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) | + | ? | + | ELISA | ||||

3.

Pathobiochemical mechanisms of elevation of class I biomarkers of fibrosis exemplified by collagens hyaluronan and laminin, respectively. Increased production by activated hepatic stellate cells due to paracrine stimulation via TGF-β by interacting cells, mechanical stress and hypoxia leads to stimulated secretion and consecutive deposition as incomplete basement membranes in the space of Disse and perisinusoidal fibrosis. As a consequence of newly developed sub-endothelial basement membrane and cellular insufficiency, the clearance function of the sinusoidal compartment for circulating matrix components is decreased and intrahepatic hemodynamic resistance is elevated. The latter leads to perihepatic shunting of blood reducing further the elimination of matrix components and their fragments from the blood.

As outlined above, TGF-β is clearly identified as a pro-fibrogenic master cytokine having a superior position in the hierarchy of fibrogenesis-stimulating growth factors. As a result, TGF-β concentrations in plasma were analysed to estimate their diagnostic significance. The concentrations are elevated in and correlated with the severity of liver diseases suggesting this cytokine as a non-invasive biomarker of hepatic dysfunction in chronic liver diseases [47], and possibly of hepatic fibrosis progression [48]. The significant correlation with aspartate-aminotransferase (AST) and alanin-aminotransferase (ALT) activity in serum [49] and the pathobiochemical finding that hepatocytes contain substantial amounts of TGF-β, which is released into the medium if hepatocytes are damaged [50], proposes that the elevation of this cytokine in serum is due to necrosis instead of fibrogenesis. Since necrosis and consecutive necro-inflammation are the driving forces of fibrogenesis, the elevation of TGF-β in serum/plasma might be an indirect clinical parameter of fibrogenesis. Additionally, decreased clearance of plasma TGF-α by impaired function of hepatocytes will contribute to its elevation in liver diseased patients [51], because parenchymal liver cells play a major role in uptake and clearance of this cytokine[52]. Furthermore, most of the circulating TGF-β is in a latent, biologically nonactive status bound to carrier proteins, for example, α2-macroglobulin [53]. Thus, measurement of TGF-β requires transient acidification before total (active and latent) TGF-β can be quantified [54].

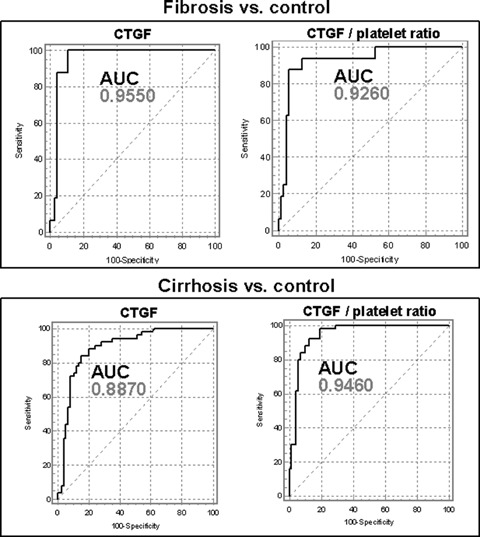

Preliminary studies point to CTGF/CCN2 in serum as an innovative class I biomarker of fibrogenesis [55]. This 38 kD protein is synthesized not only in HSC, but also in hepatocytes where the expression and secretion is strongly dependent on TGF-β[32]. Accordingly, CTGF expression in fibrotic liver tissue is up-regulated and its concentration in serum or plasma elevated if fibrogenesis is going on. There is a correlation between CTGF levels and fibrogenesis, because the levels decrease in fully developed, end-stage cirrhosis, compared to fibrosis. The area under the curve (AUCs) for fibrosis versus control and cirrhosis versus control were calculated to be 0.955 and 0.887, respectively, the sensitivities 100% and 84%, respectively, the specificities 89% and 85%, respectively (Fig. 4) [55]. These criteria suggest CTGF as a potentially valuable class I biomarker of active fibrogenesis.

4.

Receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curves of the diagnostic power of serum CTGF and of the CTGF/platelet ratio for fibrosis and cirrhosis, respectively. AUC, area under the curve. Data compiled from ref. [55].

Recently, the glycoprotein YKL-40 (‘chondrex’, molecular mass 40 kD), likely a growth factor for fibroblasts and endothelial cells, was shown to be strongly expressed in human liver tissue. In particular, HSC contain YKL-40 mRNA. Several studies have found elevated YKL-40 concentrations in sera of patients with liver diseases independent of disease etiology. Sensitivities and specificities around 80% and an AUC of 0.81 for fibrosis are reported for hepatitis C virus (HCV)-patients [56], for those with alcoholic liver disease, specificity of 88% and a low sensitivity of 51% were calculated [57]. Serum concentrations of this protein correlated with other ECM products secreted by HSC and fibroblasts, for example, PIIINP, hyaluronan, MMP-2 and TIMP-1. It is claimed that YKL-40 concentrations reflect the degree of liver fibrosis, but extensive clinical evaluation is required and other inflammatory diseases as potential conditions of YKL-40 elevations have to be excluded.

Class II fibrosis biomarkers

This category comprises a rapidly increasing, great variety of biochemical scores and multi-parameter combinations (biomarker panels), which are selected by various statistical models and mathematical algorithms, for example, multiple logistic regression analysis. They fulfil the most appropriate diagnostic criteria for detection and staging of fibrosis and to a lesser extent for grading of fibrogenesis. In general, the panels consist of rather simple (standard) laboratory tests, which are only partially related to the mechanism of fibrogenesis, but subject to changes in the serum or plasma of fibrotic and cirrhotic patients (Table 2). Several of the parameters included in the more than 20 scores currently available have no pathophysiological relation to fibrogenesis. Some of them have an indirect relation, and only few parameters can be regarded as being directly related to fibrogenesis (Table 3). The parameters measured comprise those of necrosis, such as ALT and AST, coagulation-dependent tests, transport proteins, bilirubin and some ECM-parameters. Frequently, the reduction of platelet counts in cirrhotic patients is included. Cirrhosis-associated thrombopenia is based on sequestration of platelets in the enlarged spleen, reduced thrombopoietin synthesis in the metabolically insufficient liver and increased platelet consumption. Most of the scores were developed and tested in HCV-patients and, thus, their extrapolation to non-HCV-etiologies of fibrosis must be taken with caution. The reported data for sensitivity and specificity, respectively, are compiled in Table 2, but the values frequently have a great variance among the various studies. Most prevalent multiple parameter approaches of fibrosis are the fibrotest(tm) and of necro-inflammatory activity the actitest(tm), both commercially distributed by Biopredictive, Paris, France and LabCorp, Burlington, USA. They are based on γ-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT), total bilirubin, haptoglobin, α2-macroglobulin, apolipoprotein A1 and for actitest additionally on ALT [58–60]. The data of fibrotest and actitest are calculated with a patented artificial intelligence algorithm to give measures of fibrosis stage and necro-inflammatory grade (activity), respectively. The Wai-score based on AST, alkaline phosphatase and platelet count [61], the ELF-test based on TIMP-1, PIIINP, hyaluronan [62] and the Hepascore based on bilirubin, γ-GT, hyaluronan, α2-macroglobulin, age and gender [63] are further scores with up to now limited clinical application. In particular, the fibrotest was extensively evaluated and suggested as alternative to liver biopsy for estimation of the severity of chronic HCV infection. Fibrotest was recommended to be a better predictor than biopsy staging for HCV complications and death [60]. Recently, Fibrotest and Actitest were included into biomarkers for the prediction of liver steatosis (Steato-test™), alcoholic steato-hepatitis (ASH-test™), and non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis (NASH-test™) by supplementation with serum cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose (and AST for NASH-test) adjusted for age, gender and body mass index (BMI) [64, 65] (available from LabCorp, Burlington, USA). The diagnostic criteria elaborated in a large cohort of patients suggest Steato-test as a simple and non-invasive quantitative measure of liver steatosis and the NASH-test as a useful screening procedure for advanced fibrosis and NASH in patients with various metabolic syndromes [65]. It is proposed that these scores can reduce the need for liver biopsies. FibroMax™ (Biopredictive) was recently developed as a method of combined calculation of these fibrosis-related tests in a single procedure. Comparative evaluation of class II serum biomarker panels, however, could not highlight their clinical superiority [66]. Since only about 40% of the results were assigned to be correct, a fraction of about 50–70% was inaccurate with regard to the staging of fibrosis severity and a small fraction of results was even incorrect [66]. Thus, presently suggested multi-parameter approaches with class II fibrosis biomarker panels have to be taken with caution in clinical practice. A successful approach to improve the diagnostic accuracy of the panel markers in chronic HCV might be their stepwise combination [67]. By combining the sequential algorithms of AST to platelets ratio, Forns’ index and fibrotest (Table 2) the diagnostic performance could be significantly improved resulting in a reduction of the need for liver biopsy by 50–70%[67]. However, biopsy as a ‘base-line'diagnostic procedure cannot be completely avoided [68]. However, it should be emphasized that the combination of individually assessed parameters necessarily creates relative high variance due to the imprecision of each separate measurement [69]. Coefficients of variation range from series to series between 3% and 6% for common clinical-chemical parameters and from 4% to more than 12% for hyaluronan, PIIINP, and other matrix parameters. Furthermore and even more important is the lack of standardized assays for many of these parameters, which excludes the general use of cut-offs and algorithms [69]. As an example, among the proteins included in fibrosis scores, only γ2-macroglobulin and haptoglobin can be calibrated with the ERM-DA470 reference material (ERM = European reference materials, formerly CRM-470), which is accepted in Europe, US and Japan. Similarly, only a few clinical-chemical parameters are measured on the basis of IFCC (International Federation of Clinical Chemistry) standardization, several other parameters such as, γ-GT, hyaluronan, apolipoprotein A1, TIMP-1, MMP-1 are far away from an internationally standardized reference. In addition to pre-analytical variables, ethnic differences have to be considered. These limitations argue against a general, that is, worldwide acceptance of reported cut-offs and algorithms [69].

2.

Class II Biomarkers of liver fibrogenesis

| Index | Parameters | Chronic liver disease | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGAA-Index | Prothrombin time, γGT, apolipoprotein A1, α2-macroglobulin | Alcohol | 79 | 89 | [112] |

| Bonacini-index | ALT/AST-ratio, INR, platelet count | HCV | 46 | 98 | [113] |

| Sheth-index | AST/ALT (De Ritis) | HCV | 53 | 100 | [114] |

| Park-index | HCV | 47 | 96 | [115] | |

| PGA-Index | Prothrombin time, γGT, | Mixed | 91 | 81 | [116] |

| apolipoprotein A1 | [117] | ||||

| Fortunato-score | Fibronectin, prothrombin time, PCHE, ALT, Mn-SOD, β-NAG | HCV | 94 | [118] | |

| Fibrotest | Haptoglobin, α2-macroglobulin, | HCV | 75 | 85 | [58–60] |

| (Fibro-score) | apolipoprotein A1. γGT, bilirubin | HBV | |||

| Pohl-score | AST/ALT-ratio, platelet count | HCV | 41 | 99 | [119] |

| Actitest | Fibrotest + ALT | HCV | [59] | ||

| Forns-index | Age, platelet count, γGT, cholesterol | HCV | 94 | 51 | [120] |

| Wai-index (APRI) | AST, platelet count | HCV | 89 | 75 | [61] |

| Rosenberg-score (ELF-score) | PIIINP, hyaluronan, TIMP-1 | Mixed | 90 | 41 | [62] |

| Patel-index (FibroSpect) | hyaluronan, TIMP-1, α2-macroglobulin | HCV | 77 | 73 | [121] |

| Sud-index (fibrosis probability-index, FPI) | age, AST, cholesterol, insulin resistance (HOMA), past alcohol intake | HCV | 96 | 44 | [122] |

| Leroy-Score | PIIINP, MMP-1 | HCV | 60 | 92 | [123] |

| Fibrometer test | Platelet count, prothrombin index, AST, α2-macro-globulin, hyaluronan, urea, age | Mixed | 81 | 84 | [124] |

| Hepascore | Bilirubin, γGT, hyaluronan, α2-macroglobulin, age, gender | HCV | 63 | 89 | [63] |

| Testa-index | Platelet count / spleen diameter-ratio | HCV | 78 | 79 | [125] |

| FIB-4 | Platelet count, AST, ALT, age | HCV/HIV | 70 | 74 | [126] |

| FibroIndex | Platelet count, AST, γ-globulin | HCV | 38 | 97 | [127] |

Abbreviations: GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; PIIINP, N-terminal pro-peptide of type III pro-collagen; TIMP, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases; MMP, matrix metalloproteinases; β-NAG, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; INR, international normalized ratio.

3.

Laboratory parameters included in multi-parameter scores (panels) and their potential pathogenetic link to fibrogenesis/fibrosis

| Parameter | Potential pathobiochemical basis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelets (thrombocytes) | • | Impaired synthesis due to reduced thrombopoietin production in diseased liver | ||

| • | Enhanced consumption in chronically inflamed liver by disseminated intravascular coagulation or immune mechanisms | |||

| • | Increased destruction in enlarged spleen, shortening of platelet life time | |||

| Prothrombin time (partially activated thromboplastin time) | • | Measures activity/concentration of hepatogenic coagulation factors 1, 2, 5, 8–12, indicators of liver cell protein synthesis | ||

| • | Prolongation due to decreased production in liver cell insufficiency | |||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | • | Parameter of liver cell necrosis (and apoptosis ?) | ||

| • | Leakage from cytosol and mitochondria into blood stream | |||

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | • | Parameter of liver cell necrosis (and apoptosis ?) | ||

| • | Leakage from cytosol into sinusoidal blood stream | |||

| γ-glutamyltransferase (γGT) | • | Sensitive parameter of hepatobiliary diseases (cholestasis) | ||

| • | Induction by abuse of alcohol (ethanol) and certain drugs | |||

| Pseudo-cholinesterase (PCHE) | • | Liver (hepatocyte)-specific enzyme | ||

| • | Parameter of anabolic liver cell insufficiency | |||

| Bilirubin | • | Degradation product of haemoglobin removed by hepatocytes | ||

| • | Parameter of hepato-biliary diseases | |||

| α2-macroglobulin | • | High molecular mass glycoprotein synthesized in hepatocytes, which serves as | ||

| • | proteinase inhibitor and scavenger protein, acute-phase-protein | |||

| • | Binds TGF-β, CTGF(?) and other cytokines, involved in their clearance from circulation by hepatocytes | |||

| Hyaluronan (hyaluronic acid) | • | Unsulfated, protein-free, highly polymerized glycosoaminoglycan, component of fibrotic matrix, synthesized by activated hepatic stellate cells | ||

| • | Important endogeneous ligand for Toll-like receptor TLR-4 of Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells | |||

| Cholesterol | • | Impaired synthesis in hepatocytes by HMG-CoA-reductase in advanced liver insufficiency, no obvious link to fibrogenesis | ||

| Apolipoprotein A-I | • | Component of HDL, up-regulation in and secretion by activated hepatic stellate cells, expression in hepatocytes, no obvious link to fibrogenesis | ||

| Aminoterminal pro-peptide of type III pro-collagen (PIIINP) | • | Increased production of the N-terminal split product of type III pro-collagen during fibrogenesis | ||

| Tissue inhibitor of metallo-proteinases (TIMP-1) | • | Up-regulation in fibrotic liver and in activated hepatic sellate cells, promotes progression of fibrosis through inhibition of matrix degradation | ||

| N-acetyl-β, D-glucosaminidase (β-NAG) | • | Increased activity in liver and serum in acute and chronic-active liver injury, correlation with the grade of fibrogenic activity | ||

| Haptoglobin | • | In hepatocytes synthesized acute-phase-protein, indicates inflammation but unspecific, scavenger protein for hemoglobin, antioxidans, no obvious link to fibrogenesis | ||

| HOMA, insulin resistance index | • | Hyperinsulinemia (insulin resistance) is associated with rapid fibrosis progression in HCV, insulin stimulates hepatic stellate cells to collagen synthesis, glucose up-regulates CTGF/CCN2 and TGF-β | ||

| Fibronectin | • | Matrix-associated plasma protein, increased expression in fibrotic conditions, up-regulation in activated hepatic stellate cells | ||

| Matrix metallo-proteinase-1 (MMP-1) | • | Proteolytic enzyme involved in degradation, turnover and re-modelling of extracellular matrix | ||

Genetic pre-disposition biomarkers

The pre-disposition to develop hepatic fibrogenesis is genetically complex and is the overall result of an interplay between genes and environment that is not simply following the characteristics of Mendelian disorders [70]. In addition, there are ethnic-dependent factors influencing the rate of progression and outcome of hepatic fibrogenesis. As a consequence, the ‘fibrogenic traits’ are genetically widely diverse in penetrance and progression. However, in the past there were several gene variations and polymorphisms identified that directly or indirectly increase the relative risk to develop hepatic fibrosis. In the Asian ancestry, the dependence on alcohol, which is one of the major ‘Lifestyle injurious of the liver’, was shown to be directly influenced by variations in the genes encoding alcohol dehydrogenase [71] and aldehyde dehydrogenase [72]. A similar association was found between the occurrence of a defined amino acid substitution (valine to alanine) within the mitochondrial-targeting sequence of manganese superoxide and the observed liver damage during long term alcohol abuse [73]. Although this modification does not modify alcohol consumption, the alanine-encoding allele is a major risk factor for severe alcoholic liver disease [73]. More recently, a similar functional polymorphism was found in the promoter region of the CD14 gene that causes higher serum levels of acute-phase proteins and which is a risk factor for advanced alcoholic liver disease in heavy drinkers [74].

In patients with chronic HCV infection, a functional genome-wide scan consisting of approximately 25,000 gene-centric single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), two novel markers, located in the genes encoding DEAD box polypeptide 5 (DDX5) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A) were significantly associated with advanced hepatic fibrosis [75].

Although, the precise impact of gene polymorphisms located within the coding region of the TGFB1gene is still controversially discussed [76–80] it becomes evident that the overall allelic frequencies and influence of individual gene variations on hepatic fibrogenesis is strongly dependent on other genetic factors that are fixed by ethnicity [79]. It is evident that any variation of this pro-fibrogenic cytokine that causes alterations in the biological activity (secretion, half-life) should have significant influence on the severity and progression of fibrogenesis.

Another cytokine sequence variant that was associated with the clinical outcome of hepatic fibrogenesis during chronic HCV infection is a T-to-A polymorphism at position +874 in the interferon (IFN)- γgene [81]. In addition to cytokines, several modifications in chemokines with potent leukocyte activation and/or chemotactic activity and their receptors were identified to enhance the fibrogenic response of the liver. In Europeans, defined variations of the chemokines RANTES and MCP-2 and the chemokine receptor CCR5 were shown to influence the severity of fibro-genesis during HCV infection [82]. Moreover, an amino acid exchange within the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 gene (CTLA-4) encoding a molecule that is a vital negative regulator of T cell activation was linked to the susceptibility for primary biliary cirrhosis [83]. It becomes evident that also variants of the complement system, which is relentless activated during chronic HCV infection, cause differences in the genetic susceptibility for liver fibrosis. This was demonstrated in the identification of a quantitative trait locus on chromosome 2 carrying the complement factor C5 that was correlated with liver fibrogenesis in mice and humans [84]. However, it seems that this pro-fibrogenic and pro-inflammatory effect of C5 haplotypes is co-defined by levels of vitamin-D-binding protein in blood [85].

Moreover, several isoforms of serum lipoproteins that serve as systemic carriers for hepatitis viruses are known to induce the risk to develop more severe fibrosis. For instance, a specific association of hepatic fibrogenesis in patients suffering from HCV infection were found for a apolipoprotein E isoform [86]. Interestingly, it seems that this isoform specifically increases the risk for viral induced liver damage but not for other damages that were induced by non-viral causes.

Several independent studies have further shown that elevated levels of iron that cause iron deposition and chronic inflammation are independent risk factors for liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. The C282Y mutation of the haemochromatosis gene (HFE), for example, is associated with more advanced liver disease in chronic HCV suggesting a role of HFE mutations (or higher overall concentration of iron) as primary risk factors for fibrogenesis and disease progression [87–89].

There are many other genes that are discussed in the literature as potential candidate genes influencing the pathogenesis or progression of chronic liver disease (Table 4). Some of them influence the metabolism and biological activity of substances with liver pathogenic attributes (e.g. alcohol, activity of viruses) while others act as additional risk factors (e.g. gene polymorphisms of cytokines and growth factors) corrupting the functionality of the liver. The progression rate of fibrosis and subsequent to cirrhosis varies widely among patients. It is tempting to speculate that this variation is not simply engendered by one of the gene polymorphisms mentioned above. It is more likely, that the susceptibility for fibrogenesis is generated by so called ‘SNP signatures’. A recent report investigating the impact of 361 selected SNPs for assessment of the risk for cirrhosis have shown that a cirrhotic risk signature (CRS) containing seven predictive SNPs can identify Caucasian patients with chronic hepatic C infection at high risk for cirrhosis [90]. In this study, the area-under-the receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curves of the CRS was 0.75 in a Caucasian training cohort and 0.73 in a validation cohort suggesting that CRS is a better predictor than clinical factors in differentiating high-risk versus low-risk for cirrhosis in Caucasian CHC patients [90].

4.

Summary of genes associated with pre-disposition for liver fibrosis

| Fibrogenic Mediators | Pre-disposition genes | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Alcohol dehydrogenase | [71] | ||

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase | [72] | |||

| Manganese superoxide | [73] | |||

| CD14 | [74] | |||

| Cytochrome P450IIE1 | [128] | |||

| Hepatitis C virus | DDX5 | [75] | ||

| CPT1A | [75] | |||

| Microsomal epoxide hydrolase | [129] | |||

| Growth factors/Cytokines and their receptors | TGF-β1 | [76, 79] | ||

| IL-1 receptor | [130] | |||

| IFN-γ | [81] | |||

| TNFα | [131] | |||

| IL-10 | [132] | |||

| Angiotensinogen | [76] | |||

| Chemokines and receptors | RANTES | [82] | ||

| MCP-2 | [82] | |||

| CCR5 | [82] | |||

| Serum lipoproteins | Apo E | [86, 133] | ||

| Immune- and complement system | CTLA-4 | [83] | ||

| TAP2 | [134] | |||

| Human leukocyte antigens (HLA) | [130] | |||

| Complement factor C5 | [84] | |||

| Iron metabolism | Haemochromatosis gene (HFE) | [87] | ||

Abbreviations used are: ApoE, apolipoprotein E; CCR5, CC motif receptor 5; CPT1A, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4; DDX5, DEAD box polypeptide 5; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL, interleukin; MCP-2, Macrophage chemoattractant protein 2; RANTES, Regulated upon Activation, Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted;TAP2, transporter associated with antigen processing 2; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α.

Although it is tempting to speculate that some of the gene markers that were reported so far as genetic pre-disposition markers for hepatic fibrogenesis have great potential, none of them has actual relevance in routine diagnosis or prognosis of fibrosis susceptibility. Further, large-scale, well-designed association studies will prove the efficacy of potential new genetic tests.

Future developments

Growing understanding of the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis indicates potentially powerful non-invasive (blood) biomarkers of hepatic fibrogenesis and fibrosis (Table 5). CTGF/CCN2 was already mentioned as an important, pluripotent downstream modulator of growth factors, in particular of TGF-β, and was found to be up-regulated by TGF-β in hepatocytes. Although most of CTGF will only have a defined paracrine function in fibrogenic tissue, a certain fraction spillsover into the circulation, resulting in elevated serum concentrations during active fibrogenesis [55]. Preliminary data justify the optimism that the circulating level of CTGF might be an objective and sensitive readout of ongoing fibrogenesis in necro-inflammatory liver tissue.

5.

Future candidate biomarkers of non-invasive diagnosis and follow-up of liver fibrogenesis

| Biomarker | Specimen | Assay technology | Pathobiochemical basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTGF | Serum | Immunoassay | TGF-β induced expression in and secretion by hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells |

| Fibrocytes | Blood, buffy coat | Flow cytometry of CD34+, CD45+, Coll I+ cells QPCR | Supplementation of local fibroblasts at site of liver injury by bone-marrow derived fibrocytes |

| BMP-7 | Serum | Immunoassay | Antagonist of TGF-β, inhibitor of EMT |

| G-CSF GM-CSF M-CSF | Blood | Immunoassays | Mobilization of bone-marrow derived fibrocytes |

| 13C-Methace-tin breath test | Expiratory air | Miniaturized spectroscopy and continuous breath sampling | Reflects hepatic microsomal function of CYP450 1A2 |

| Proteomics | Serum | Mass spectrometry (MS) | Fibrosis-specific serum protein profiles |

| Glycomics | Serum | Adaptation of DNA-sequencer/fragment analyser technology to profiling of desialylated N-linked oligo-saccharides | Fibrosis-specific profiles of desialylated serum protein linked oligosaccharides (N-glycans) |

| Xylosyl-transferase (EC 2.4.2.26) | Serum | LC-MS/MS | Key enzyme in the biosynthesis of glycosaminoglycan chains in proteoglycans, e.g. in hepatic stellate cells |

The description of bone-marrow-derived fibrocytes might offer new approaches not only for the understanding of the pathogenesis, but also for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis. Fibrocytes are circulating progenitor cells (CD34 positive) of haematopoietic origin (CD45 positive) capable of differentiating into diverse mesenchymal cell types [21]. The additional markers of fibrocytes, i.e., positivity of type I collagen and the CXCR4 chemokine expression can be used to quantitate this special sub-population of circulating leucocytes in the buffy coat or even in the circulation applying quantitative PCR and/or flow cytometry. The determination of the colony-stimulating factors M-CSF, G-CSF and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which are increasingly expressed in fibrotic liver tissue and elevated in serum [91, 92], are possibly involved in the mobilisa-tion of fibrocytes from the bone marrow and their homing in the liver during fibrogenesis. They might be further candidates for diagnostic evaluation.

A new, but presently still controversial aspect of fibrogenesis is EMT as outlined above. EMT is governed by the balance of TGF-β (pro-EMT) and its antagonist, that is, BMP-7 (anti-EMT). In addition to its anti-EMT effect, BMP-7 was shown to have anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory activities. Thus, the measurement of BMP-7 alone or even in relation to TGF-β in serum might reflect the activity of fibrogenesis and, hence, the velocity of fibrotic organ transition. Elevated BMP-7 levels and up-regulated expression in hepatocytes of cirrhotic livers in situ were reported [93].

Xylosyltransferase, a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of glycosaminoglycans in proteoglycans, was shown to have increased activities in serum of patients with connective tissue diseases, for example, systemic sclerosis, osteoarthritis and pseudoxanthoma elasticum. With highly sensitive and automated methods (high-performance liquid chromatography [HPLC]-tandem mass spectrometry) measurements in large cohorts of liver fibrotic patients seem to be possible [94]. Since HSC in fibrotic liver tissue (MFB) have a greatly stimulated proteoglycan synthesis [95, 96] xylosyltransferase activity in serum might also be a promising class I biomarker of fibrogenesis.

Recently proposed point of care non-invasive 13C-methacetin breath testing for identifying a significant inflammation and fibrosis or NAFLD provides optimistic data for significant fibrosis (METAVIR > 2) with sensitivities and specificities of 96% and 86%, respectively [97]. This liver function test measures microsomal activity of cytochrome P4501A2, which is related to inflammation and fibrosis. Evaluation in large cohorts is necessary.

Further successful developments could emerge from serum proteom profiling [98] and from total serum protein glycomics, that is, the pattern of N-glycans [99]. It was reported that a unique serum pro-teomic finger print is identified in the sera of patients with fibrosis, which enables differentiation between different stages of fibrosis and a prediction of fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with a chronic hepatitis B infection [98]. Specificities and sensitivities and accuracy of prediction of cirrhosis are around 89%. Similarly, N-glycan profiling can distinguish between compensated cirrhosis from non-cirrhotic chronic liver diseases with sensitivity and specificity of 79% and 86%, respectively [99]. Besides pushing forward new parameters, the refinement of already existing class I biomarkers will be promising. As an example, the differentiation of low and high molecular weight fractions of hyaluronan, specific immunoassays of the core-proteins of proteoglycans synthesized in activated stellate cells (i.e. biglycan, decorin), and TGF-β-related components (i.e. latency associated protein of TGF-β and latent TGF-β-binding protein) are rational candidates of new or refined biomarkers. The evaluation of all these non-invasive diagnostic tools remains a complicated matter because of the limitations of the presently available ‘gold standard’ liver biopsy described above [6]. Although the histologic evaluation of biopsy specimens provides a unique source of grading and staging of inflammation, steatosis, fibrosis, cirrhosis and neoplasia considerable sampling variability, inter and intraobserver variance and insensitive semiquantative numerical scores are major analytical drawbacks. Recently developed methods of quantitative morphometric image analysis partially overcome these limitations [100], but the diagnostic power remains dependent on good sample quality [100] and expertise of the observer. Thus, a tissue cyinder of at least 25 mm length is necessary to evaluate fibrosis correctly [4].

Supplementation of all these techniques by modern high resolution or even molecular imaging analyses would be extremely helpful in the consolidation of objective and valid non-invasive biomarkers of diagnosis and follow-up of fibrogenic (liver) disease. These include ultrasound [101, 102], magnetic resonance imaging [103] and transient elastography [104]. The latter method (FibroScan™), Echosens, France), a specially adapted pulse-echo ultrasound technique, uses the principle of one-dimensional transient elas-tography to measure liver stiffness. This method appears as a reliable tool to detect significant fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic HCV [105, 106] and was even superior to fibrotest [107]. FibroScan may be particular useful to monitor patients longitudinally after a baseline biopsy has been performed [108]. The combination with serum fibrosis markers further improves the accuracy to the diagnosis of significant fibrosis (Metavir F ≤ 2) [109, 110]. In conclusion, currently available type I and II serum biomarkers should be used with caution, because neither single nor panel markers fulfil the requirements of an ideal non-invasive biomarker of fibrosis [111], that is, analytical simplicity allowing performance in any laboratory, standardization of the test system and calibrators allowing comparison between the laboratories over a long period, cost effectiveness, specificity for the liver and the disease, clear association with the stage of fibrosis or grade of fibrogenesis and independency of the etiology of the fibrosis (e.g. alcoholic, HCV, B and others). Even the relative best and most extensively evaluated type I (i.e. hyaluronan) and type II (i.e. fibrotest, actitest) serum biomarkers do not meet the criteria of an ideal marker. Further detailed insight into the mechanism of liver fibrosis and improvement of analytical techniques will result in new approaches for non-invasive assessment of fibrosis with biochemical or physical means. In addition, the analysis of genetic pre-disposition markers or the determination of special SNPs signatures that are associated with the severity of fibrosis will potentially complement serum analytic, proteom profiling, and the non-invasive fibrosis staging testing.

References

- 1.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–18. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinzani M, Rombouts K. Liver fibrosis: from the bench to clinical targets. Digest Liver Dis. 2004;36:231–42. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman SL, Rockey DC, Bissell DM. Hepatic fibrosis 2006: Report of the third AASLD Single Topic Conference. Hepatology. 2007;45:242–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedossa P, Dargere D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afdhal NH, Nunes D. Evaluation of Liver Fibrosis: A Concise Review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1160–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regev A, Berho M, Jeffers LJ, Milikowski C, Molina EG, Pyrsopoulos NT, Feng ZZ, Reddy KR, Schiff ER. Sampling error and intraobserver variation in liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2614–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinzani M. Hepatic stellate (Ito) cells: expanding roles for a liver-specific pericyte. J Hepatol. 1995;22:700–6. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gressner AM, Bachem MG. Molecular mechanisms of liver fibrogenesis - a homage to the role of activated fat-storing cells. Digestion. 1995;56:335–46. doi: 10.1159/000201257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gressner AM. Transdifferentiation of hepatic stellate cells (Ito cells) to myofibroblasts: a key event in hepatic fibrogenesis. Kidney Int. 1996;49:S39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Modern pathogenetic concepts of liver fibrosis suggest stellate cells and TGF-beta as major players and therapeutic targets. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:76–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geerts A. History, heterogeneity, developmental biology, and functions of quiescent hepatic stellate cells. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:311–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jezequel AM, Novelli G, Venturini C, Orlandi F. Quantitative analysis of the perisinusoidal cells in human liver; the lipocytes. Front Gastrointestinal Res. 1984;8:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wake K. Hepatic stellate cells: Three-dimensional structure, localization, heterogeneity and development. Proc Jpn Acad. 2006;82:155–64. doi: 10.2183/pjab.82.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blomhoff R, Wake K. Perisinusoidal stellate cells of the liver: important roles in retinol metabolism and fibrosis. FASEB J. 1991;5:271–7. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.3.2001786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winau F, Hegasy G, Weiskirchen R, Weber S, Cassan C, Sieling PA, Modlin RL, Liblau RS, Gressner AM, Kaufmann SHE. Ito cells are liver-resident antigen-presenting cells for activating T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;26:117–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maubach G, Lim MCC, Kumar S, Zhuo L. Expression and upregulation of cathepsin S and other early molecules required for antigen presentation in activated hepatic stellate cells upon IFN-[gamma] treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res. 2007;1773:219–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JS, Semela D, Iredale J, Shah VH. Sinusoidal remodeling and angiogenesis: A new function for the liver-specific pericytes? Hepatology. 2007;45:817–25. doi: 10.1002/hep.21564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of disease: mechanisms of hepatic fibrosis and therapeutic implications. Nat Clin Pract Gastr. 2004;1:98–105. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schramm C, Protschka M, Kohler HH, Podlech J, Reddehase MJ, Schirmacher P, Galle PR, Lohse AW, Blessing M. Impairment of TGF-beta signaling in T cells increases susceptibility to experimental autoimmune hepatitis in mice. Am J Physiol-Gastroint Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G525–35. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00286.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinnman N, Francoz C, Barbu W, Wendum D, Rey C, Hultcrantz R, Poupon R, Housset C. The myofi-broblastic conversion of peribiliary fibrogenic cells distinct from hepatic stellate cells is stimulated by platelet-derived growth factor during liver fibrogenesis. Lab Invest. 2003;83:163–73. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000054178.01162.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan TE, Cowper S, Wu SP, Bockenstedt LK, Bucala R. Circulating fibrocytes: collagen-secreting cells of the peripheral blood. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forbes SJ, Russo FP, Rey V, Burra P, Rugge M, Wright NA, Alison MR. A significant proportion of myofibroblasts are of bone marrow origin in human liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:955–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisseleva T, Uchinami H, Feirt N, Quintana-Bustamante O, Segovia JC, Schwabe RF, Brenner DA. Bone marrow-derived fibrocytes participate in pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2006;45:429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba S, Fujii H, Hirose T, Yasuchika K, Azuma H, Hoppo T, Naito M, Machimoto T, Ikai I. Commitment of bone marrow cells to hepatic stellate cells in mouse. J Hepatol. 2004;40:255–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romagnani P, Lasagni L, Romagnani S. Peripheral blood as a source of stem cells for regenerative medicine. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2006;6:193–202. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1776–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI20530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R, Breitkopf K, Dooley S. Roles of TGF-b in hepatic fibrosis. Front Biosci. 2002;7:D793–07. doi: 10.2741/A812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bissell DM, Roulot D, George J. Transforming growth factor b and the liver. Hepatology. 2001;34:859–67. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zavadil J, Böttinger EP. TGF-beta and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. Oncogene. 2005;24:5764–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leask A, Abraham DJ. All in the CCN family: essen-tial matricellular signaling modulators emerge from the bunker. J Cell Sci. 2006:119. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI31139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gressner O, Lahme B, Demirci I, Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Differential effects of TGF-beta on connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) expression in hepatic stellate cells and hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2007;47:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galli A, Crabb DW, Ceni E, Salzano R, Mello T, Svegliati-Baroni G, Ridolfi F, Trozzi L, Surrenti C, Casini A. Antidiabetic thiazolidinediones inhibit collagen synthesis and hepatic stellate cell activation in vivo and in vitro. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1924–40. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu JA, Danielsson A. Detection of hepatic fibrogenesis: A review of available techniques. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:817–25. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuppan D, Stölzel U, Oesterling C, Somasundaram R. Serum assays for liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:82–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horslev-Petersen K. Circulating extracellular matrix components as markers for connective tissue response to inflammations. Dan Med Bull. 1990;37:308–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plebani M, Burlina A. Biochemical markers of hepatic fibrosis. Clin Biochem. 1991;24:219–39. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(91)80013-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lydatakis H, Hager IP, Kostadelou E, Mpousmpoulas S, Pappas S, Diamantis I. Non-invasive markers to predict the liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2006;26:864–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guechot J, Laudat A, Loria A, Serfaty L, Poupon R, Giboudeau J. Diagnostic accuracy of hyaluronan and type III procollagen amino terminal peptide serum assays as markers of liver fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis C evaluated by ROC curve analysis. Clin Chem. 1996;42:558–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gressner AM, Haarmann R. Hyaluronic acid synthesis and secretion by rat liver fat storing cells (perisi-nusoidal lipocytes) in culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;151:222–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guéchot J, Poupon RE, Poupon R. Serum hyaluro-nan as a marker of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:103–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collazos J, Diaz F. Role of the measurement of serum procollagen type III N-terminal peptide in the evaluation of liver diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 1994;227:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kropf J, Gressner AM, Negwer A. Efficacy of serum laminin measurement for diagnosis of fibrotic liver diseases. Clin Chem. 1988;34:2026–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gressner AM, Tittor W, Kropf J. The predictive value of serum laminin for portal hypertension in chronic liver diseases. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 1988;35:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kropf J, Gressner AM, Tittor W. Logistic-regression model for assessing portal hypertension by measuring hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan) and laminin in serum. Clin Chem. 1991;37:30–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gressner AM, Tittor W, Negwer A, Pick-Kober KH. Serum concentrations of laminin and aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen in relation to the portal venous pressure of fibrotic liver diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 1986;161:249–58. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(86)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flisiak R, Prokopowicz D. Transforming growth factor-b1 as a surrogate marker of hepatic dysfunction in chronic liver diseases. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2000;38:1129–31. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2000.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flisiak R, Pytelkrolczuk B, Prokopowicz D. Circulating transforming growth factor beta(1) as an indicator of hepatic function impairment in liver cirrhosis. Cytokine. 2000;12:677–81. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flisiak R, Maxwell P, Prokopowicz D, Timms PM, Panasiuk A. Plasma tissue inhibitor of metallopro-teinases-1 and transforming growth factor beta 1 -Possible non-invasive biomarkers of hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic B and C hepatitis. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 2002;49:1369–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roth S, Michel K, Gressner AM. (Latent) transforming growth factor-beta in liver parenchymal cells, its injury-dependent release and paracrine effects on hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 1998;27:1003–12. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayasaka A, Suzuki N, Fukuyama E, Kanda Y. Plasma levels of transforming growth factor beta1 in chronic liver disease. Clin Chim Acta. 1996;244:117–9. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(95)06201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coffey RJ, Kost LJ, Lyons RM, Moses HL, LaRusso NF. Hepatic processing of transforming growth factor beta in the rat. Uptake, metabolism, and biliary excretion. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:750–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI113130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grainger DJ, Kemp PR, Metcalfe JC, Liu AC, Lawn RM, Williams NR, Grace AA, Schofield PM, Chauhan A. The serum concentration of active transforming growth factor-beta is severely depressed in advanced atherosclerosis. Nature Med. 1995;1:74–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grainger DJ, Mosedale DE, Metcalfe JC, Weissberg PL, Kemp PR. Active and acid-activated TGF-beta in human sera, platelets, and plasma. Clin Chim Acta. 1995;235:11–31. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(94)05995-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gressner AM, Yagmur E, Lahme B, Gressner O, Stanzel S. Connective tissue growth factor in serum as a new candidate test for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1815–7. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.070466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saitou Y, Shiraki K, Yamanaka Y, Yamaguchi Y, Kawakita T, Yamamoto N, Sugimoto K, Murata K, Nakano T. Noninvasive estimation of liver fibrosis and response to interferon therapy by a serum fibro-genesis marker, YKL-40, in patients with HCV-associated liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:476–81. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i4.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tran A, Benzaken S, Saint-Paul MC, Guzman-Granier E, Hastier P, Pradier C, Barjoan EM, Demuth N, Longo F, Rampal P. Chondrex (YKL-40), a potential new serum fibrosis marker in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:989–93. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Imbert-Bismut F, Ratziu V, Pieroni L, Charlotte F, Benhamou Y, Poynard T. Biochemical markers of liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;357:1069–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poynard T, McHutchison J, Manns M, Myers RP, Albrecht J. Biochemical surrogate markers of liver fibrosis and activity in a randomized trial of peginter-feron alfa-2b and ribavirin. Hepatology. 2003;38:481–92. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Poynard T, Imbert-Bismut F, Munteanu M, Messous D, Myers R, Thabut D, Ratziu V, Mercadier A, Benhamou Y, Hainque B. Overview of the diagnostic value of biochemical markers of liver fibrosis (FibroTest, HCV FibroSure) and necrosis (ActiTest) in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Comp Hepatol. 2004;3:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok ASF. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–26. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenberg WMC, Voelker M, Thiel R, Becka M, Burt A, Schuppan D, Hubscher S, Roskams T, Pinzani M, Arthur MP. Serum markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1704–13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adams LA, Bulsara M, Rossi E, DeBoer B, Speers D, George J, Kench J, Farrell G, McCaughan GW, Jeffrey GP. Hepascore: An Accurate Validated Predictor of Liver Fibrosis in Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1867–73. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.048389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ratziu V, Giral P, Munteanu M, Messous D, Mercadier A, Bernard M, Morra R, Imbert-Bismut F, Bruckert E, Poynard T. Screening for liver disease using non-invasive biomarkers (FibroTest, SteatoTest and NashTest) in patients with hyperlipidaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:207–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Poynard T, Ratziu V, Naveau S, Thabut D, Charlotte F, Messous D, Capron D, Abella A, Massard J, Ngo Y, Munteanu M, Mercadier A, Manns M, Albrecht J. The diagnostic value of biomarkers (SteatoTest) for the prediction of liver steatosis. Comp Hepatol. 2005;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parkes J, Guha IN, Roderick P, Rosenberg W. Performance of serum marker panels for liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:462–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sebastiani G, Vario A, Guido M, Noventa F, Plebani M, Pistis R, Ferrari A, Alberti A. Stepwise combination algorithms of non-invasive markers to diagnose significant fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44:686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sebastiani G, Alberti A. Non invasive fibrosis bio-markers reduce but not substitute the need for liver biopsy. World J Gastroenterology. 2006;12:3682–94. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i23.3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosenthal-Allieri MA, Peritore ML, Tran A, Halfon P, Benzaken S, Bernard A. Analytical variability of the Fibrotest proteins. Clin Biochem. 2005;38:473–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Juran BD, Lazaridis KN. Genomics and complex liver disease: Challenges and opportunities. Hepatol. 2006;44:1380–90. doi: 10.1002/hep.21453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whitfield JB. Meta-analysis of the effects of alcohol dehydrogenase genotype on alcohol dependence and alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol. 1997;32:613–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomasson HR, Crabb DW, Edenberg HJ, Li TK, Hwu HG, Chen CC, Yeh EK, Yin SJ. Low Frequency of the ADH2*2 Allele among Atayal Natives of Taiwan with Alcohol Use Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:640–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Degoul F, Sutton A, Mansouri A, Cepanec C, Degott C, Fromenty B, Beaugrand M, Valla D, Pessayre D. Homozygosity for alanine in the mito-chondrial targeting sequence of superoxide dismutase and risk for severe alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1468–74. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Campos J, Gonzalez-Quintela A, Quinteiro C, Gude F, Perez LF, Torre JA, Vidal C. The -159C/T polymorphism in the promoter region of the CD14 gene is associated with advanced liver disease and higher serum levels of acute-phase proteins in heavy drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1206–13. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171977.25531.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang H, Shiffman ML, Cheung RC, Layden T, Friedman S, Abar OT, Yee L, Chokkalingam AP, Schrodi SJ, Chan J, Catanese JJ, Leong DU, Ross D, Hu X, Monto A, McAllister LB, Broder S, White T, Sninsky JJ, Wright TL. Identification of two gene variants associated with risk of advanced fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1679–87. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Powell EE, Edwards-Smith CJ, Hay JL, Clouston AD, Crawford DHG, Shorthouse C, Purdie DM, Jonsson JR. Host genetic factors influence disease progression in chronic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2000;31:828–33. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.6253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gewaltig J, Mangasser-Stephan K, Gartung C, Biesterfeld S, Gressner AM. Association of polymorphisms of the transforming growth factor- 1 gene with the rate of progression of HCV-induced liver fibrosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;316:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00738-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tag CG, Mengsteab S, Hellerbrand C, Lammert F, Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Analysis of the transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) codon 25 gene polymorphism by LightCycler-analysis in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Cytokine. 2003;24:173–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang H, Mengsteab S, Tag CG, Gao CF, Hellerbrand C, Lammert F, Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Transforming growth factor-beta1 polymorphisms are associated with progression of liver fibrosis in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis C infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1929–36. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i13.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Osterreicher CH, Datz C, Stickel F, Hellerbrand C, Penz M, Hofer H, Wrba F, Penner E, Schuppan D, Ferenci P. TGF-[beta]1 codon 25 gene polymorphism is associated with cirrhosis in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis. Cytokine. 2005;31:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dai CY, Chuang WL, Hsieh MY, Lee LP, Hou NJ, Chen SC, Lin ZY, Hsieh MY, Wang LY, Tsai JF, Chang WY, Yu ML. Polymorphism of interferon-gamma gene at position +874 and clinical characteristics of chronic hepatitis C. Transl Res. 2006;148:128–33. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hellier S, Frodsham AJ, Hennig BJW, Klenerman P, Knapp S, Ramaley P, Satsangi J, Wright M, Zhang L, Thomas HC, Thursz M, Hill AVS. Association of genetic variants of the chemokine receptor CCR5 and its ligands, RANTES and MCP-2, with outcome of HCV infection. Hepatology. 2003;38:1468–76. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Agarwal K, Jones DEJ, Daly AK, James OFW, Vaidya B, Pearce S, Bassendine MF. CTLA-4 gene polymorphism confers susceptibility to primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:538–41. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hillebrandt S, Wasmuth HE, Weiskirchen R, Hellerbrand C, Keppeler H, Werth A, Schirin-Sokhan R, Wilkens G, Geier A, Lorenzen J, Kohl J, Gressner AM, Matern S, Lammert F. Complement factor 5 is a quantitative trait gene that modifies liver fibrogenesis in mice and humans. Nat Genet. 2005;37:835–43. doi: 10.1038/ng1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gressner O, Meier U, Hillebrand S, Wasmuth HE, Kohl J, Sauerbruch T, Lammert F. Gc-globulin concentrations and C5 haplotype-tagging polymorphisms contribute to variations in serum activity of complement factor C5. Clin Biochem. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.02.001. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wozniak MA, Itzhaki RF, Faragher EB, James MW, Ryder SD, Irving WL. Apolipoprotein E-epsilon 4 protects against severe liver disease caused by hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2002;36:456–63. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smith BC, Grove J, Guzail MA, Day CP, Daly AK, Burt AD, Bassendine MF. Heterozygosity for hereditary hemochromatosis is associated with more fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 1998;27:1695–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Erhardt A, Maschner-Olberg A, Mellenthin C, Kappert G, Adams O, Donner A, Willers R, Niederau C, Haussinger D. HFE mutations and chronic hepatitis C:H63D and C282Y heterozygosity are independent risk factors for liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2003;38:335–42. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Geier A, Reugels M, Weiskirchen R, Wasmuth HE, Dietrich CG, Siewert E, Gartung C, Lorenzen J, Bosserhoff AK, Brugmann M, Gressner AM, Matern S, Lammert F. Common heterozygous hemochromatojnsis gene mutations are risk factors for inflammation and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2004;24:285–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang H, Shiffman ML, Friedman SL, Venkatesh R, Bzowej N, Abar OT, Rowland CM, Catanese JJ, Leong DU, Sninsky JJ, Layden TJ, Wright TL, White T, Cheung RC. A 7 gene signature identifies the risk of developing cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;46:297–306. doi: 10.1002/hep.21695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kubota A, Okamura S, Omori F, Shimoda K, Otsuka T, Ishibashi H, Niho Y. High serum levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in patients with liver cirrhosis and granulocytopenia. Clin Lab Haematol. 1995;17:61–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.1995.tb00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pinzani M, Abboud HE, Gesualdo L, Abboud SL. Regulation of macrophage colony-stimulating factor in liver fat-storing cells by peptide growth factors. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C876–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.4.C876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tacke F, Gäbele E, Bataille F, Schwabe RF, Hellerbrand C, Klebl F, Straub RH, Luedde T, Manns MP, Trautwein C, Brenner DA, Schölmerich J, Schnabl B. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 is elevated in patients with chronic liver disease and exerts fibrogenic effects on human hepatic stellate cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9758-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kuhn J, Prante C, Schon S, Gotting C, Kleesiek K. Measurement of fibrosis marker xylosyltransferase I activity by HPLC electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2006;52:2243–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.071167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gressner AM. Activation of proteoglycan synthesis in injured liver–A brief review of molecular and cellular aspects. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1994;32:225–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]