Abstract

Purpose

Medical student mistreatment has been recognized for decades and is known to adversely impact students both personally and professionally. Similarly, burnout has been shown to negatively impact students. This study assesses the prevalence of student mistreatment across multiple medical schools and characterizes the association between mistreatment and burnout.

Method

In 2011, the authors surveyed a nationally representative sample of third-year medical students. Students reported the frequency of mistreatment by attending faculty and residents since the beginning of their clinical rotations. Burnout was measured using a validated two-item version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Results

Of 919 eligible students from 24 different medical schools, 564 (61%) completed the survey. The majority reported at least one incident of mistreatment by faculty (64% [361/562]) and by residents (75.5% [426/562]). Notable minorities experienced recurrent mistreatment, defined as mistreatment categorized as “several” or “numerous” times by student self-report (10.7% [59/562] by faculty and 12.6% [71/562] by residents). Recurrent mistreatment was associated with high burnout (57.4% vs. 31.5%; p<0.01 for recurrent mistreatment by faculty; 49.1% vs. 32.1%; p<0.01 for recurrent mistreatment by residents).

Conclusions

Medical student mistreatment remains prevalent. Recurrent mistreatment by faculty and residents is associated with medical student burnout. Although further investigation is needed to assess causality, these data provide additional impetus for medical schools to address student mistreatment to mitigate its adverse consequences on their personal and professional well-being.

Introduction

Medical student mistreatment was initially described in 1982 by Henry Silver who highlighted its similarities to child abuse.1 Subsequent studies have found that the majority of medical students in the United States experience some form of mistreatment during training.2-9 Reported mistreatment ranges from gender and racial discrimination to physical intimidation to public belittlement and humiliation. Clinical faculty and residents are the most commonly identified sources, but other perpetrators include nurses, ancillary staff, and even other students. The experience of mistreatment during training is not unique to the U.S. Studies in other countries describe similar problems.10-12

Despite increased awareness and denunciation of the practice, as well as numerous institutional initiatives13-15, medical student mistreatment persists. The prevalence of mistreatment is tracked predominantly by the annual Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Graduation Questionnaire (GQ), which has documented a relatively stable rate of reported mistreatment from 20.3% in 2000 to 16.8% in 2011 with a low of 12.2% in 2006.16,17 In 2012, the GQ was revised to eliminate the so-called gateway question (“Have you personally been mistreated during medical school?”) and to instead inquire only about the specific behaviors students may have experienced.18 The GQ, however, surveys students retrospectively at the end of medical school, asking them to recall events over their entire medical school experience. This may easily lead to underreporting. Several recent studies, including one large multi-institutional study, suggest mistreatment may be more common than indicated by the GQ.19,20

Medical student mistreatment is problematic both in its effects on the learning environment and its potentially harmful effects on student well-being and professional choices. Mistreatment correlates with poor emotional and mental health outcomes such as problem drinking, decreased self-confidence and self-esteem, and depression.21,22 Additionally, mistreatment is associated with increased thoughts of dropping out of medical school, lower career satisfaction, and regret for having chosen the profession of medicine.23 For example, according to one study, mistreated students are less likely to plan careers in academic medicine.24 Some medical students may demonstrate symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder following mistreatment.25 In sum, mistreatment may have potentially serious and long-lasting consequences.

Student mistreatment may lead to burnout.26 The most widely used measure of burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory which defines burnout as consisting of a combination of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of others, and a feeling of reduced personal accomplishment.27 Burnout is common among medical professionals including physicians, nurses, and dentists. 28-30 A recent national survey reported a 45.8% burnout rate among US physicians with variations depending on specialty31. One study showed that burnout is prevalent among residents who are just starting training.32 Among medical students, burnout has a negative impact on professional behaviors and attitudes, empathy, and personal well-being.33-36 While burnout has many contributing causes, we theorized that mistreatment may be one of the more common factors. We aimed to determine the prevalence of medical student mistreatment in a nationally representative sample of third year students and to assess whether mistreatment is associated with burnout.

Method

Our study was conducted as part of a larger longitudinal project examining the professional development of physicians from medical school into residency training.37 Relevant to the present analysis, we surveyed third year medical students from 24 LCME-accredited medical schools in the U.S. between January and April 2011. To construct our target sample, we selected 960 students from 24 LCME-accredited medical schools in the U.S. using a two-stage sample design. In stage one, we selected schools with probabilities proportional to total enrollment so that the larger schools would have a greater chance of being included in the study. Data for medical school sampling was obtained from published reports. In stage two, we used simple random sampling to select a fixed number of students (40) from each selected school. This two-stage procedure is an efficient way of including large schools (where the “typical” medical student attends) while evening out student weights to reduce the effect of disproportional school selection on test statistics.

The student sample was obtained from the American Medical Association Physician Professional Data (Masterfile), which has a near-complete listing of students pursuing M.D. degrees at schools within the U.S. and its territories. Students who were not in their third year of medical school were excluded.

Prior to administration, the survey underwent expert review by colleagues as well as cognitive pre-testing with a group of third year medical students from our institution. Students were asked whether they had experienced mistreatment using the following questions, “Since the beginning of your clinical rotations, how many times have you been mistreated by an attending faculty” and “Since the beginning of your clinical rotations, how many times have you been mistreated by an intern or resident?” Neither definitions nor examples of mistreatment were given. Response categories were “never, “once or twice”, “a few times”, “several times”, and “numerous times.” For the analysis, we classified mistreatment as never, infrequent, or recurrent. Mistreatment was categorized as infrequent if it occurred “once or twice” or “a few times” and recurrent if it occurred “several times” or “numerous times.”

We assessed burnout using a validated two-item version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory.38 Respondents were asked about the frequency of statement accuracy in two domains: emotional exhaustion (“I feel burned out from my work”) and depersonalization (“I have become more callous toward people since I took this job”). High burnout was identified by a response of at least weekly for one or both of the items. The rest of the respondents were categorized as having low or average burnout.

We collected contextual information about the respondents which we felt might be relevant to their risk of burnout including basic demographics, background characteristics, and factors related to their medical training. Demographic information was limited to gender and race. Background information about each respondent included their immigration history (born in the U.S. or immigrated to the U.S.), whether they grew up in a medically underserved setting, and whether they had a physician parent or grandparent. Respondents were also asked about their expected total student debt load (pre-medical and medical), specialty intentions (primary care versus non-primary care), and medical school information (private or public school and region of the country). Intention to enter primary care was defined as reporting that one will likely enter family medicine, internal medicine, or pediatrics and reporting that one is likely to pursue primary care. All other career plans were classified as non-primary care including those intending to enter family medicine, internal medicine, or pediatrics but unlikely to pursue primary care.

The University of Chicago Social and Behavioral Sciences institutional review board approved the study and waived written consent. Each potential respondent received a letter in advance of the study explaining the survey and its voluntary nature and asking for confirmation of mailing address. A total of three requests were sent via email and the United States Postal Service. With the initial survey mailing, a $5 bill was enclosed as an incentive to complete the survey and with the last request, a $10 gift card was offered as an additional incentive. Each respondent was given a unique identifier in order to track responses, however, all data were de-identified prior to analysis.

Quantitative data were analyzed using STATA (version 12.1; Stata Corporation, College Station TX). For statistical analysis, we excluded responses that were left blank because of respondent omission. Case weights were employed to reflect sources of variance associated with the sample design and to adjust for potential nonresponse bias. Groups were compared using chi-square analysis with significance determined by alpha = .05.

Results

Of 960 potential respondents, 605 (63%) returned partial or complete surveys. Respondents were excluded from the analysis if they were not currently in their third year of medical school due to time away from school or other reasons (n = 41).

The demographics and other characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. Respondents were almost evenly divided between male and female (306 of 564 [54%] vs. 258 of 564 [46%]). The majority were Caucasian (329 of 564 [58%]). Our sample was similar in its percentages of women and minorities in medicine when compared to known demographics of U.S. medical students nationally.39 Twenty-five percent of respondents (138 of 563) stated they grew up in a medically underserved setting. Twenty-two percent (123 of 563) had a physician parent or grandparent. The majority of respondents (394 of 561 [70%]) had expected total student debt of more than $100,000. Thirty-four percent (193 of 564) stated they intended to pursue a career in primary care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of a nationally representative sample of third-year medical student respondents, 2011

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Student Demographics | |

| Gender (N=564) | |

| Male | 306 (54%) |

| Female | 258 (46%) |

| Race / Ethnicity (N=562) | |

| White or Caucasian | 349 (62%) |

| Asian | 128 (22%) |

| Black or African American | 48 (10%) |

| Hispanic | 3 (1%) |

| Other | 34 (6%) |

| Student Background | |

| Immigration History (N=561) | |

| Immigrated to United States | 95 (16%) |

| Born in United States | 466 (84%) |

| Grew Up in Medically Underserved Setting (N=563) | |

| Yes | 138 (25%) |

| No | 425 (75%) |

| Physician Parent or Grandparent (N=563) | |

| Yes | 123 (21%) |

| No | 44 (79%) |

| Medical Education Experience | |

| Total Expected Student Debt Load (N=561) | |

| None | 61 (11%) |

| Less than $100,000 | 106 (19%) |

| $100,000-200,000 | 227 (40%) |

| More than $200,000 | 167 (31%) |

| Specialty Intention (N=564) | |

| Primary Care | 198 (35%) |

| Non-primary care | 366 (65%) |

| Medical School Sector (N=564) | |

| Public | 368 (62%) |

| Private | 196 (38%) |

| Medical School Region (N=564) | |

| Northeast | 137 (25%) |

| South | 204 (38%) |

| Midwest | 147 (25%) |

| West | 76 (13%) |

N varies throughout due to non-response. Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding.

The vast majority of respondents in our survey had experienced at least one incident of mistreatment by either a faculty member or a resident (466 of 562 [83%]). Sixty-four percent (361 of 562) of respondents had experienced mistreatment by faculty, while 75.5% (426 of 562) had experienced mistreatment by a resident. Most respondents who had experienced mistreatment reported mistreatment by both faculty and residents (321 of 466 [68.9%]).

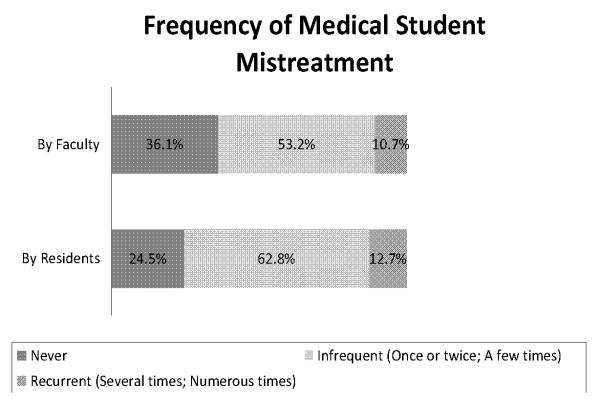

As seen in Figure 1, the majority of respondents who experienced mistreatment reported infrequent mistreatment (mistreatment reported to occur “once or twice” or “a few times”). However, recurrent mistreatment (mistreatment reported to occur “several” or “numerous” times) was not uncommon. Recurrent mistreatment by faculty was reported by 10.7% (59 of 562) of respondents while 12.6% (71 of 562) had experienced recurrent mistreatment by residents. Recurrent mistreatment was not associated with any of the collected student or medical school characteristics.

Figure 1.

Frequency of self-reported medical student mistreatment by faculty and by residents in a nationally representative sample of third-year medical students (n = 562). The infrequent mistreatment category included students who reported mistreatment “once or twice” or “a few times”. The recurrent mistreatment category included students who reported mistreatment “several times” or “numerous times”.

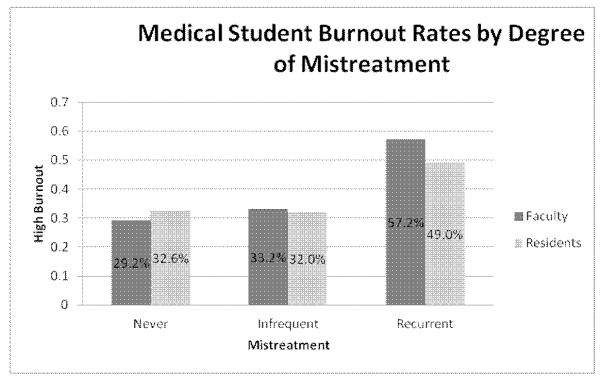

Overall, high burnout identified by the abbreviated Maslach Burnout Inventory was observed for 34.1% (192 of 561) of the respondents. However, as seen in Figure 2, there were differences in burnout rates by degree of mistreatment. Compared to those students who reported no or infrequent mistreatment, those students who experienced recurrent mistreatment by faculty were significantly more likely to score high on the burnout measure (57.4% vs. 31.5%; p<0.01). The same was true for those who had experienced recurrent mistreatment by residents (49.1% vs. 32.1%; p<0.01). None of the other examined factors including gender, race, immigration history, student debt load, specialty intention, or medical school characteristics were significantly associated with high burnout.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of high burnout in a nationally representative sample of third-year medical students by degree of reported mistreatment by faculty and by residents (n = 561) Burnout assessed by validated two-item version of Maslach Burnout Inventory.34 Mistreatment categorized by student self-report. The infrequent mistreatment category included students who reported mistreatment “once or twice” or “a few times”. The recurrent mistreatment category included students who reported mistreatment “several times” or “numerous times”.

Discussion

The prevalence of mistreatment in our sample of third-year medical students was much higher than we expected based on the recent AAMC GQ data. The prevalence of mistreatment in our study was in the same range as those reported in older studies,7,8 whereas it was much higher compared to the recent rates reported in the AAMC GQ (16.8% in 2011), and that despite the fact that the students in our study had completed fewer clinical rotations. It is possible, however, that the discrepancy is the result of students taking the GQ failing to recall episodes of mistreatment occurring early in their clinical years. Alternatively, students may become habituated over time and perceive less mistreatment by the end of medical school. The rates of recurrent mistreatment in our sample correspond more closely to the reported mistreatment rates in the GQ, suggesting that at the end of medical school, students may not recall or report less frequent episodes of mistreatment. Periodic assessments of medical students in their clinical years may provide a more accurate picture of mistreatment than a single retrospective survey at graduation.

The cohort of students in our study would have graduated in 2012, the first year of the revised GQ. The 2012 GQ All Schools Summary Report states that 47.1% of students reported they had personally experienced one or more of the listed behaviors.18 This percentage is higher than those found in previous versions of the GQ, which used the earlier gateway question.13 This 47.1% prevalence is similar to what we found in the present study, although direct comparisons are difficult to make because we used different questions than the GQ. The revised GQ may provide not only more accurate information about rates of mistreatment but also more actionable information about the specific behaviors and sources of mistreatment. Such information is likely to help institutions as they work to reduce student mistreatment.

From the very first descriptions of medical student mistreatment, there have been doubts about whether student reports can be trusted as accurate.2 Many believe students are overly sensitive to the actions and behaviors of others as they adjust to the unfamiliar demands and pressures of the clinical environment. Hence, the predominant concern about student-reported mistreatment is that students misperceive events as mistreatment directed towards them when others including educators and administrators may not judge these events in the same manner. In 2005, Ogden and colleagues provided evidence that in fact, medical students perceive events similar to the way attending physicians, residents, and nurses view the same events.40 Furthermore in 2013, Bursch and colleagues demonstrated that there was no association between student identification of abuse in hypothetical scenarios on an abuse sensitivity questionnaire and their report of personal mistreatment.41 While there are undoubtedly some misunderstandings, student report remains our standard measure of mistreatment.

Unlike burnout, there is no accepted measurement tool for mistreatment. Despite the large literature on medical student mistreatment, the validity of various questionnaires has not been established. Almost all studies of mistreatment have relied on student self-report. How the questions are asked and whether or not examples are given may affect the results. In 2011, the AAMC GQ provided instruction to students that mistreatment “occurs when behavior shows disrespect for the dignity of others and unreasonably interferes with the learning process. Examples of mistreatment include sexual harassment; discrimination or harassment based on race, religion, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation; humiliation, psychological or physical punishment and the use of grading and other forms of assessment in a punitive manner.”17 Prior versions of the GQ did not provide examples.42,43 Nevertheless, the rates of student mistreatment reported in the GQ has remained relatively stable over time and the GQ remains the accepted reference standard.

Another common argument about mistreatment is that it is simply part of the cultural of medical training.44.45 There is a temptation to view these aspects of training as a reality that students must accept as part of their chosen profession. In 2009, Haglund and colleagues examined the experiences and responses of medical students to events occurring on their clinical rotations.46 While there was evidence that students are resilient to traumatic events involving patient suffering and death, students exposed to personal mistreatment and poor role modeling by their superiors did not demonstrate resilience but instead showed higher depression and stress. That study suggests there is a distinction between events that provide opportunities for personal reflection and growth and those that merely diminish the student’s sense of well-being. Just because mistreatment has persisted for so long does not mean it is an inevitable or necessary experience of medical training.

Residents play a key role in the education of medical students, and many residency programs provide formal training to prepare residents for their role as teachers.47,48 Unfortunately, residents can also be the perpetrators of medical student mistreatment. In our study, residents were more commonly sources of mistreatment than faculty. Given that residents are still in training themselves, there are added opportunities for programmatic intervention and education about student mistreatment.13,49 Promotion of a positive learning environment will necessarily involve institutional change, but beginning with resident education may be one promising strategy to mitigate mistreatment. Faculty development is another target but less attention has been paid to this idea except in the context of institutional change.49-51

In our study, recurrent mistreatment both by clinical faculty and by residents was associated with medical student burnout. While we cannot discern cause and effect in this cross-sectional analysis, it seems plausible that recurrent mistreatment of students contributes to their burnout. Multiple incidents of mistreatment may make students more vulnerable to the symptoms of burnout, even in their first year of clinical rotations. Conversely, it is also possible that burnout stemming from causes other than mistreatment may prime students to be more likely to recall or interpret faculty and resident actions as mistreatment, thereby leading to our observed association.

Burnout has multi-factorial origins that are both social and personal.52 Prevention of burnout will need to address both of those domains. More study is necessary to determine what makes certain students vulnerable to burnout. One may wonder what are the characteristics of students who reported high mistreatment but low burnout and furthermore, whether those characteristics were innate or learned. Resilience may play a role in preventing some students from experiencing burnout despite situational challenges such as mistreatment.

There are several limitations to this study. First, we do not have mistreatment information about the non-respondents, and it is conceivable that non-respondents may differ in their experiences in ways that bias our findings. For example, if students with high rates of mistreatment or burnout were more likely to respond, our estimate of the prevalence of mistreatment may be too high. The converse may also be true. This may be less likely since the survey was not primarily presented as a study about mistreatment or burnout. Second, mistreatment was evaluated by student report only which is subject to recall biases that may lead to inaccurate estimates. In addition, we do not have detailed information about the type or severity of episodes of mistreatment. We do not know if incidents were clustered around particular faculty, residents, or clinical rotations. Additionally, there are other psychological and mental health factors, such as stress, depression, and coping skills which we did not measure but which may influence student burnout levels. Finally, as a cross-sectional survey, this study can demonstrate associations but not causation.

We conclude that medical student mistreatment remains frequent despite many efforts to address this issue. The association between medical student mistreatment and burnout is an important area for future research given that both may independently cause adverse personal and professional outcomes for the student.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Annikea Miller for her assistance in data collection, and Michael Leffel for his expert consultation throughout the project.

Funding/Support: This project was supported by A New Science of Virtues, The Arete Initiative at the University of Chicago through a grant from the John Templeton Foundation as well as a grant from the Center of Health Administration Studies and a pilot award from the Clinical and Translational Science Award – Institute for Translational Medicine (#UL1 RR024999).

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the University of Chicago Social and Behavioral Sciences institutional review board.

Disclaimers: None

Previous presentations: An abstract with this data was presented at the Research in Medical Education Conference during the annual meeting of the Association of American Medical Colleges, November 5, 2012, San Francisco, California and at the Academic Internal Medicine Week, October 12, 2012, Phoenix, Arizona.

Contributor Information

Alyssa F. Cook, Dr. Cook is a fellow, Medical Education Research, Innovation, Teaching, and Scholarship program, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois..

Vineet M. Arora, Dr. Arora is associate professor, Department of Medicine, assistant dean, Scholarship & Discovery program, and associate program director, Internal Medicine Residency program, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois..

Kenneth A. Rasinski, Dr. Rasinski was assistant professor, Department of Medicine and is survey manager, Chicago Consortium for School Research, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Farr A. Curlin, Dr. Curlin is associate professor, Department of Medicine, co-director, Program on Medicine and Religion, and associate faculty, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois..

John D. Yoon, Dr. Yoon is assistant professor, Department of Medicine, and associate faculty, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois..

References

- 1.Silver HK. Medical students and medical school. JAMA. 1982;247:309–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg DA, Silver HK. Medical student abuse: an unnecessary and preventable cause of stress. JAMA. 1984;251:739–742. doi: 10.1001/jama.251.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin DC, Daugherty SR, Eckenfels EJ, Leksas L. The experience of mistreatment and abuse among medical students. Res Med Educ. 1988;27:80–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silver HK, Glicken AD. Medical student abuse: Incidence, severity, and significance. JAMA. 1990;263:527–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin DC, Daugherty SR, Eckenfels EJ. Student perceptions of mistreatment and harassment during medical school: A survey of ten United States schools. West J Med. 1991;155:140–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolf TM, Randall HM, von Almen K, Tynes LL. Perceived mistreatment and attitude change by graduating medical students: a retrospective study. Med Educ. 1991;25:182–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson DA, Becker M, Frank RR, Sokol RJ. Assessing medical students’ perceptions of mistreatment in their second and third years. Acad Med. 1997;72:728–730. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199708000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangus RS, Hawkins CE, Miller MJ. Prevalence of harassment and discrimination among medical school graduates: A survey of eight US schools. JAMA. 1998;280:852–855. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.9.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassebaum DG, Cutler ER. On the culture of student abuse in medical school. Acad Med. 1998;73:1149–1158. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhari M, Kokkonen J, Nuutinen M, et al. Medical student abuse: an international phenomenon. JAMA. 1994;271:1049–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.13.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagata-Kobayashi S, Sekimoto M, Koyama H, et al. Medical student abuse during clinical clerkships in Japan. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:212–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rees CE, Monrouxe LV. A morning since eight of just pure grill: A multischool qualitative study of student abuse. Acad Med. 2011;86:1374–1382. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182303c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heru AM. Using role playing to increase residents’ awareness of medical student mistreatment. Acad Med. 2003;78:35–38. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karnieli-Miller O, Vu TR, Holtman MC, Clyman SG, Inui TS. Medical students’ professionalism narrative: a window on the informal and hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2010;85:124–133. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c42896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried JM, Vermillion M, Parker NH, Uijtdehaage S. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: a longitudinal study of one institution’s efforts. Acad Med. 2012;87:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182625408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamagata H, Haviland MG, Werner LS, Sabharwal RK. [Accessed May 28, 2013];Recent trends in the reporting of medical student mistreatment. Analysis in Brief 2006;6. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/102340/data/aibvol6no4.pdf.

- 17.Association of American Medical Colleges . Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2011 All Schools Summary Report. Association of American Medical Colleges; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Association of American Medical Colleges . Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2012 All Schools Summary Report. Association of American Medical Colleges; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton R, Bickel J, Nora LM. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C. doi:10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C (published 6 September 2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried JM, Vermillion M, Parker NH, Uijtdehaage S. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: A longitudinal study of one institution’s efforts. Acad Med. 2012;87:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182625408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richman JA, Flaherty JA, Rospenda KM, Christensen ML. Mental health consequences and correlates of reported medical student abuse. JAMA. 1992;267:692–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubitz RM, Nguyen DD. Medical student abuse during third-year clerkships. JAMA. 1996;275:414–416. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.5.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV, White K, Leibowitz A, Baldwin DC. A pilot study of medical student ‘abuse’: Student perceptions of mistreatment and misconduct in medical school. JAMA. 1990;263:533–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haviland MG, Yamagata H, Werner LS, Zhang K, Dial TH, Sonne JL. Student mistreatment in medical school and planning a career in academic medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23:231–237. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2011.586914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heru A, Gagne G, Strong D. Medical student mistreatment results in symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33:302–306. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.33.4.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: Causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1613–22. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maslach C, Jackson S. Burnout in health professions: A social psychological analysis. In: Sanders G, Suls J, editors. Social psychology of health and illness. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288:1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff. 2011;30:202–210. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rada RE, Johnson-Leong C. Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:788–794. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Litjen T, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ripp J, Fallar R, Babyatsky M, David R, Reich L, Korenstein D. Prevalence of resident burnout at the start of training. Teach Lean Med. 2010;22:172–75. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2010.488194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Eacker A, et al. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA. 2010;304:1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brazeau CMLR, Schroeder R, Rovi S, Boyd L. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med. 2010;85:S33–S36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4c47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, et al. Burnout and suicidal ideation among U. S. medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:334–341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Power DV, et al. Burnout and serious thoughts of dropping out of medical school: A multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2010;85:94–102. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c46aad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leffel GM, Mueller RA, Rasinski KA, Yoon JD, Curlin FA. Project on the Good Physician: Report #1: Evidence for the Construct Validity of a Moral Intuitionist Model of Virtuous Caring. The New Science of Virtues Project. 2013 (Manuscript in reivew) [Google Scholar]

- 38.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Singe item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24:1318–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Association of American Medical Colleges Data Warehouse [Accessed May 28, 2013];Student file. Table 28: Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race and Ethnicity within Sex, 2002-2011. Revised February 17, 2012. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/download/158404/data/

- 40.Ogden PE, Wu EH, Elnicki MD, et al. Do attending physicians, nurses, residents, and medical students agree on what constitutes medical student abuse? Acad Med. 2005;80:S80–S83. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510001-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bursch B, Fried JM, Wimmers PF, et al. Relationship between medical student perceptions of mistreatment and mistreatment sensitivity. Med Teach. 2013;35:e998–e1002. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.733455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Association of American Medical Colleges . Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2009 All Schools Summary Report. Association of American Medical Colleges; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- 43.Association of American Medical Colleges . Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: 2010 All Schools Summary Report. Association of American Medical Colleges; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neville AJ. In the age of professionalism, student harassment is alive and well. Med Ed. 2008;42:447–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frase-Blunt M, Hall AC. [Accessed May 28, 2013];Rude Medicine: Are hazing, harassment and abuse an inevitable part of training? The New Physician. 2007 56 Available at: http://www.amsa.org/AMSA/Homepage/Publications/TheNewPhysician/2007/tnp372.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haglund MEM, Ann Het Rot M, Cooper NS, et al. Resilience in the third year of medical school: A prospective study of the associations between stressful events occurring during clinical rotations and student well-being. Acad Med. 2009;84:258–268. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819381b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mann KV, Sutton E, Frank B. Twelve tips for preparing residents as teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29:301–306. doi: 10.1080/01421590701477431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill AG, Yu TC, Barrow M, Hattie J. A systematic review of resident-as-teacher programmes. Med Educ. 2009;43:1129–1140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldstein EA, Maestas RR, Fryer-Edwards K, et al. Professionalism in medical education: An institutional challenge. Acad Med. 2006;81:871–875. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000238199.37217.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Humphrey HJ, Smith K, Reddy S, Scott D, Madara JL, Arora VM. Promoting an environment of professionalism: the University of Chicago “Roadmap”. Acad Med. 2007;82:1098–1107. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000285344.10311.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wasserstein AG, Brenna PJ, Rubenstein AH. Institutional leadership and faculty response: fostering professionalism at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2007;82:1049–1056. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31815763d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maslach C, Goldberg J. Prevention of burnout: new perspectives. Appl Prev Psychol. 1998;7:63–74. [Google Scholar]