Abstract

High-valent terminal metal-oxygen adducts are hypothesized to be the potent oxidising reactants in late transition metal oxidation catalysis. In particular, examples of high-valent terminal nickel-oxygen adducts are sparse, meaning there is a dearth in the understanding of such oxidants. In this study, a monoanionic NiII-bicarbonate complex was found to react in a 1:1 ratio with the one-electron oxidant tris(4-bromophenyl)ammoniumyl hexachloroantimonate, yielding a thermally unstable intermediate in high yield (~95%). Electronic absorption, electronic paramagnetic resonance and X-ray absorption spectroscopies and density functional theory calculations confirm its description as a low-spin (S = ½), square planar NiIII-oxygen adduct. This rare example of a high-valent terminal nickel-oxygen complex performs oxidations of organic substrates, including 2,6-ditertbutylphenol and triphenylphosphine, which are indicative of hydrogen atom abstraction and oxygen atom transfer reactivity, respectively.

Keywords: reactive intermediates, oxidation catalysis, metal-oxo, high-valent nickel, model complexes

Introduction

Nature employs Fe- and Cu-containing oxygenases to perform hydrocarbon oxidation and Mn-containing photosystem II to perform water oxidation.[1] Similarly, many synthetic Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Cu-containing catalysts are capable of both hydrocarbon and water oxidation.[2] In most of these natural and non-natural first-row transition metal catalysed conversions, terminal high-valent metal-oxygen adducts, such as metal-oxo (M=O), metal-oxyl (M-O·) or metal-hydroxo (M-OH) intermediates, have been implicated as the reactive oxidants. These oxidants are potent hydrogen atom abstraction (HAA) or oxygen atom transfer (OAT) reagents, capable of activating some of the most inert of substrates. Many examples of enzymatic and synthetic terminal oxomanganese and oxoiron species have arisen in the past 10 years,[3] however there remains a dearth in the number of terminal late transition metal-oxygen adducts (metal = Co, Ni, Cu). Ray/Nam and Tolman have recently made great strides in preparing the first examples of scandium(III)oxocobalt(IV) and hydroxocopper(III) species, respectively.[4] However, well-characterized high-valent terminal nickel-oxygen adducts remain elusive.

Synthetic nickel containing complexes have been exploited as catalysts for the oxidation of hydrocarbons[5] and water.[6] Similarly, nickel-containing films and nanoparticles have been employed as oxidation catalysts.[2b,7] Terminal high-valent nickel-oxygen adducts (NiIII/IV–OX) have been postulated as the active oxidant in these systems, however, very few such species have been isolated and well-characterized to date.[5,8] Interestingly, computational studies have forecast that a NiIII=O species would be capable of the activation of the strongest of C–H bonds (CH4, bond dissociation energy (BDE) = 104 kcal/mol).[9]

Several groups have attempted to prepare high-valent nickel-oxygen adducts, for example Ray reported that the oxidation of [NiII(TMG3tren)(OTf)](OTf) (TMG3tren = (tris[2-(N-tetramethylguanidyl)ethyl]amine, OTf = trifluoromethanesulfonate) with 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid produced two species claimed to be NiIII–O(X) complexes.[10] However, the low yield (15%) of NiIII and identification of at least two NiIII species in the reaction mixture hampered their characterization. Latos-Grażyński reacted a NiIII–Br complex with hydroxide to yield a new species that was claimed to be a NiIII–OH complex.[11] However, this species was only characterized using EPR spectroscopy, and no reactivity studies were performed. Liaw prepared NiIII–OR (R = Me, Ph) species, but did not report on their HAA or OAT reactivity properties.[12] Interestingly, several μ-oxo-dinickel(III)[13] and nickel-containing heterobimetallic μ-oxo-complexes[14] have been isolated and found to be effective HAA reagents. In contrast, there remains a lack of suitable high-valent terminal nickel-oxygen adducts that could help us understand further the reactivity properties of late transition metal oxidants. With this in mind, we set out to prepare, characterize and investigate the reactivity of such complexes. We identified Holm’s [NiII(OH)(pyN2Me2)]– (1, Scheme 1) and [NiII(OCO2H)(pyN2Me2)]– (2, Scheme 1) complexes (pyN2Me2 = bis(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-2,6-pyridinedicarboxamidate) as excellent candidates for the generation of high-valent terminal nickel-oxygen adducts.[15] Using similar 2,6-pyridinedicarboxamidate ligands, thermally stable NiIII and NiIV complexes,[16] as well as CuII–superoxide,[17] and CuIII–OH[4c,18] entities have been isolated. Herein, we describe the oxidation of 2 (which is formed from the reaction between 1 and CO2, Scheme 1), to yield a metastable NiIII–O(X) species that displays the ability to perform HAA and OAT.

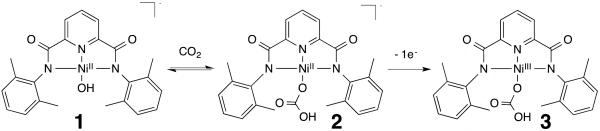

Scheme 1.

Complexes 1[15a], 2[15a], and 3. Schematic representation of the preparation of 2 and 3.

Results and Discussion

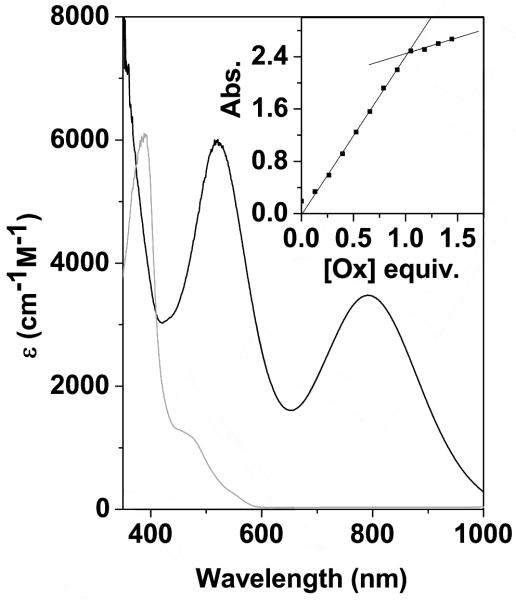

In acetone, at −80 °C, 2 was reacted with the organic oxidant tris(4-bromophenyl)ammoniumyl hexachloroantimonate[19] (‘Magic-Blue’, dissolved in CH3CN, E°’ = 0.70 V vs Fc+/Fc[20]). An instantaneous reaction was observed as evidenced by the appearance of two intense features in the electronic absorption spectrum (λmax = 520 and 790 nm, Figure 1), assigned to a novel species 3. A titration of Magic Blue against 1 showed that the intensity of the new features reached a maximum after the addition of one equivalent of Magic Blue (Figure 1, inset). The addition of greater than one equivalent of Magic Blue did not cause a further change in the new features, while the presence of excess unreacted Magic Blue in the reaction mixture was observed in the electronic absorption spectrum (Figure S1). Initial indications thus suggested that 2 had been oxidized by one electron yielding a novel species, 3, that we postulate is a NiIII–OCO2H complex.

Figure 1.

UV-vis spectrum of 2 (grey trace, 0.4 mM in acetone) that was reacted with Magic Blue at −80 °C to yield 3 (black trace). Inset: Titration of Magic Blue with 2 monitored by plotting the intensity of the λmax = 520 nm feature versus equivalents of Magic Blue.

The intense absorption features in the visible and near-IR (NIR) regions of the UV-vis spectrum, observed upon the reaction between 2 and Magic Blue to yield 3, suggest a change in the oxidation state of the Ni center. Many of the NiIII complexes reported to date display similarly intense chromophores in the visible and NIR regions of their absorption spectra.[10,12,16,21] Intermediate 3 could be generated in acetone or THF. The features associated with 3 are the same in both solvents. Likewise, when 3 was prepared in the presence or absence of excess CH3CN (acetone or CH3CN can be used as the solvent for Magic Blue) no difference in the electronic absorption features was noted. These observations are important as they demonstrate that solvent is not coordinating to the NiIII center in 3. Should solvent coordinate to the NiIII center in 3, one would anticipate different UV-vis characteristics of the oxidized product in different solvent media.

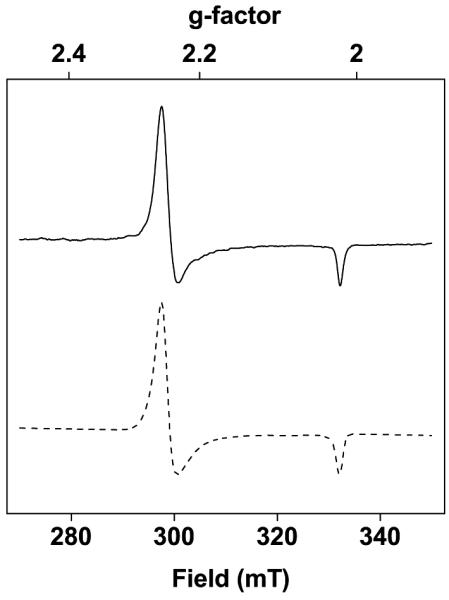

3 was further characterized using X-band electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. An acetone solution of 3 was frozen in liquid nitrogen and an axial spectrum was obtained at 113 K (Figure 2, g = 2.25, 2.02). The yield of NiIII was calculated to be 95% (±15%) by double integration of the signal of 3 against that of a radical standard (TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidin-1-yl)oxyl)). The obtained g-values are consistent with an S = ½ (low-spin) d7 NiIII species,[21d,22] and the average g-value (gav. = 2.17) is indicative of the unpaired electron sitting on the Ni-center, rather than being a ligand-based radical. Importantly, g⊥ » g∥ which is typical for axially elongated octahedral complexes or square planar complexes.[21b,21d,22-23]

Figure 2.

Solid trace: X-band EPR spectrum of 3 in a frozen acetone solution. Measured at 113 K; microwave power = 31.6 mW; modulation amplitude = 0.5 mT; g⊥ = 2.25, g∥ = 2.02, gav. = 2.17. Dashed trace: simulated spectrum for 3. The system was modelled as an S = ½ electron spin with axial g tensor, and inhomogeneous line broadening. The greater line broadening in the x and y directions is possibly due to unresolved hyperfine coupling with the 14N nuclei of the ligand.

The most likely configurations for a low-spin d7 ion in pseudo-tetragonal symmetry involve the unpaired electron density being located in an orbital of predominant dz2 or dxy character. Instances where g⊥ » g∥ have been usually understood to correspond to a dz2 singly-occupied orbital.[21b,21d,22,23b,23d] In all, the EPR analysis suggests that oxidation of the square-planar precursor 2 resulted in the loss of an electron yielding a square-planar S = ½ d7 NiIII species, 3, with a metal-based dz2-like occupied orbital. Density functional theory (DFT) Mulliken spin density calculations were performed in order to further probe the location of the unpaired electron density in 3. These calculations supported the experimental observations that the unpaired spin predominantly resides in a metal-based molecular orbital. The DFT calculations predict that either metal-based dz2- or dxy-like molecular orbitals are the likely locations of the unpaired electron density (Figure 3 displays spin density plot for dz2 occupancy). The DFT calculations thus support the EPR determined electronic structure of 3.

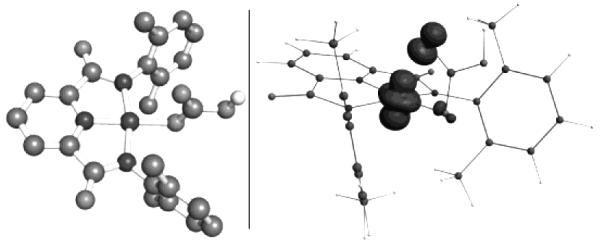

Figure 3.

Left: DFT optimized structure of 3. Hydrogen atoms (except bicarbonate proton) have been excluded for clarity. Right: DFT optimized spin density plot of 3.

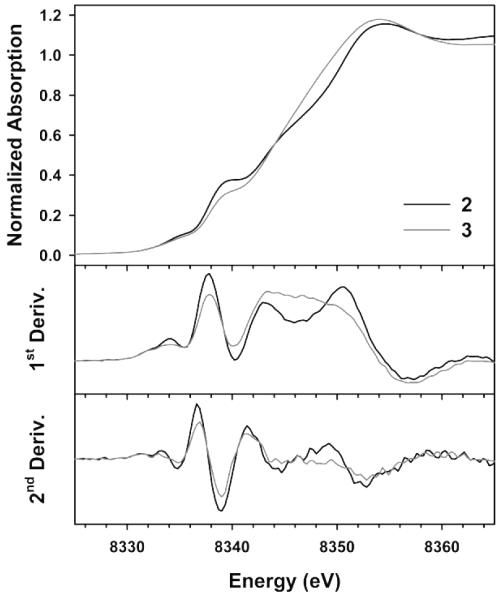

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was employed to analyse the electronic and structural properties of 3. The XAS edge energy measured for 3 (8345 eV) lies in the expected range for NiIII complexes.[14,24] Interestingly, there is only a very minor shift in the K-edge energy compared to the K-edge energy measured for NiII-containing 2 (Figure 4). This is not unusual for Ni (and indeed Cu) K-edge analysis, several groups have made similar observations when comparing NiII/III species within comparable coordination environments.[24a,25] Contributions to the edge from 1s → 4p absorption features distort the edge and prevent accurate assessment of the edge shift upon oxidation of 2 to yield 3. The derivatives of the normalized X-ray absorption near-edge spectrum (XANES) indicate a modest edge shift of 0.1 - 0.2 eV when comparing the 1s → 3d pre-edge transition of 2 to 3, in accord with increased oxidation of the Ni center in 3. Although there appears to negligible change in the edge energy between 2 and 3, the shape of the edge and relative intensities of features in the edge are markedly different. Such differences are indicative of the distinct electronic environments of the Ni-center in complexes 2 and 3.

Figure 4.

XANES spectra of 2 (black trace) and 3 (grey trace), along with associated first and second derivatives.

Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis of 3 yielded a disordered first coordination shell of 4 O/N donors (Figure S2, Table S1). This shell could be split into two components with two scatterers at ~ 1.84 Å and two scatterers at ~ 1.99 Å giving the best fit of the experimental data obtained for 3 (Table 1). These observations suggest that a single-bonded oxygen ligand is present in 3, i.e. the bicarbonate remains intact. Attempts to fit the data containing a very short Ni–O bond (~1.65 Å) resulted in very poor fits, ruling out the possibility of 3 being a NiIII=O species. Comparison of the EXAFS fits for 2 and 3 suggests there are little to no structural differences in the two complexes. The fits acquired for 2 match well with the X-ray diffraction determined bond distances obtained for 2.[15a] We have employed DFT to further understand the structural properties of 3 (Table 1, Figure 3). The DFT predictions indicate that the bicarbonate ligand in 3 would remain bound in a monodentate fashion, in good agreement with the EXAFS analyses of a first coordination sphere of 4 donors. Furthermore, the computational analyses predicted that the d7 NiIII ion in 3 would remain in a square planar coordination environment analogous to that seen for 2, in good agreement with the EPR measurements that indicate the NiIII ion sits in a square planar environ. DFT also predicted that the Ni–OCO2H and Ni–N(py) bond distances in 3 would be 1.96 Å and 1.84 Å (Table 1), respectively, in reasonably good agreement with the EXAFS analyses showing two O/N scatterers at ~1.84 Å. The combination of EXAFS and DFT predictions shows that the Ni center in 3 has remained 4-coordinate, in a square planar environment, and that the bicarbonate ligand is present.

Table 1.

Nickel-ligand bond distances for 2 and 3 as determined using aXRD, bEXAFS and cDFT

| Ni–OCO2H | Ni–N(py) | Ni–N(amid) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 a [15a] | 1.871 | 1.817 | 2 @ 1.895 |

| 2 b | 4 @ 1.87 | ||

| 2 b | 1.90 | 1.80 | 2 @ 1.90 |

| 3 b | 2 @ 1.84 | 2 @ 1.99 | |

| 3 c | 1.96 | 1.84 | 2 @ 1.93 |

It is important to note that the obtained EXAFS data could also be reasonably well fit with a –OH ligand (in place of –OCO2H). Holm et al demonstrated that 2 reversibly binds CO2, and it is reasonable to suggest the affinity of 3 for CO2 may be less than for 2.[15a,15b,15d] We endeavored to probe 3 using Raman spectroscopy, but failed to identify peaks that confirmed the presence of either –OH or –OCO2H ligands. We were hampered by the rich Raman spectrum of the acetone support medium. We also failed in our efforts to obtain mass spectrometric evidence for the molecular formula of 3, presumably as a result of the low thermal stability of 3. It is important to note that oxidation of 1 with Magic Blue does not yield the same spectroscopic features attributed to 3, but in fact yields an as yet unidentified species. We therefore conclude that 3 maintains the coordinated –OCO2H ligand.

3 was stable at −80 °C, but decayed upon warming above −40 °C. After thermal decay and acidic workup of the reaction mixture, the protonated ligand (H2pyN2Me2) was recovered without any indications of ligand oxidation (no evidence for ligand hydroxylation or oxidative decomposition was obtained by mass spectrometry or 1H NMR spectroscopy). Interestingly, ESI-MS analysis showed the presence of trace amounts of hydroxyacetone, pyruvic acid and acetic acid.[26] Importantly, at −40 °C, the half-life of 3 in [H6]acetone was 5600 s whereas in [D6]acetone it was found to be 6800 s (kinetic isotope effect (KIE) = 1.2). The observation of such acetone-derived products and an extended lifetime in perdeuterated solvent supports the postulate that 3 oxidizes acetone by rate-limiting HAA during its thermal decay. This is an important discovery (acetone contains a very strong C–H bond (BDE = 93 kcal/mol[27]), suggesting that 3 is a very capable oxidant.

We investigated further the HAA reactivity of 3 towards external substrates by reacting it with molecules containing somewhat weaker X–H bonds (X = C, O, we were limited in our substrate scope by solubility issues at low temperature). At −40 °C, 3 reacted with 100 equiv. of 2,6-ditertbutylphenol (DTBP), as evidenced by the disappearance (600 s) of the electronic absorption features attributed to 3 (Figure S3). This resulted in the appearance of a new band at λmax = 555 nm, which we attribute to the formation of the phenoxyl radical as a result of HAA from DTBP by 3.[28] EPR analysis confirmed the formation of a phenoxyl radical (Figure S4). After warming to room temperature, 3,3',5,5'-tetra-tert-butyl-[1,1'-bi(cyclohexane)]-2,2',5,5'-tetraene-4,4'-dione (Scheme S1) and traces of 2,6-ditertbutylquinone were detected using GC-MS. Such products form by radical coupling or thermal decomposition, respectively, of the parent 2,6-ditertbutylphenoxyl radical. A pseudo first-order rate constant (kobs) for this reaction was determined by plotting the change in absorbance features for 3 against time and fitting the resulting curve (Figure S5). A second-order rate constant (k2) was calculated from the slope of a linear plot of kobs-values determined under a series of substrate concentrations (Figure S6). The k2-value determined for the reaction between 3 and DTBP was 0.1040 M−1s−1, while for deutero-DTBP a k2-value of 0.0503 M−1s−1 was determined, yielding a KIE value of 2.1. This KIE value is consistent with 3 performing HAA on the DTBP O–H bond, and with HAA being rate-limiting.

3 was also found to react with 1-benzyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide (BNAH, C–H bond dissociation energy (BDE) = 68 kcal/mol)) at −80 °C, as evidenced by a rapid disappearance of the visible absorption features attributed to 3 (Figure S7). The product of this reaction was identified by 1H NMR as 1-benzyl-1-pyridinium-3-carboxamide, which typically forms as a result of HAA from the C–H bond of BNAH. This product formed as a result of a two-electron oxidation of BNAH. We assume this occurs through initial HAA from BNAH followed by an electron transfer from the resultant product to another molecule of 3. In summary, 3 was found to be a quite reactive HAA reagent capable of activating O–H and C–H bonds at low temperatures.

We also probed the capacity of 3 to carry out OAT. 3 was reacted with triphenylphosphine (PPh3, 50 equiv.) at −80 °C resulting in the formation of triphenylphosphine oxide (O=PPh3, detected by ESI-MS and 31P NMR) in near quantitative yields (Figure S8). OAT is a two-electron transfer process, thus the formation of O=PPh3 from this reaction would be expected to yield a NiI product. We do not observe such a NiI species, but rather only NiII products. Presumably, the formed NiI product reacts with another molecule of 3 (similar to the BNAH oxidation) to yield the observed NiII products. Interestingly, 3 was completely consumed by just 0.5 equivalents of PPh3 and BNAH, confirming our suspicions about the mechanisms of its reductive decay. A second-order rate constant (k2) for the reaction between 3 and PPh3 was determined (5.3 M−1s−1, Figures S9 & S10). This k2-value for PPh3 oxidation is quite high compared to values determined for Fe=O and Mn=O complexes in the same reaction[29] We believe it is quite significant that the Ni-species displayed such a high rate constant. 3 was also found to be highly reactive towards one-electron reductants. Ferrocene (1 equiv. in acetone) reacted with 3 instantaneously at −80 °C, as evidenced by the disappearance of UV-vis features attributed to 3, and the formation of new features in the visible region that can be attributed to the ferrecenium cation (λmax = 630 nm, Figure S11). The conversion of ferrocene to ferrocenium was quantitative, the yield of ferrocenium was determined to correspond to exactly one equivalent of 3 being reduced. 3 thus represents an exciting example of a terminal Ni-oxygen adduct that is capable of HAA, OAT and electron transfer.

Conclusions

In summary, the one-electron oxidation of 2 at low temperature generates a NiIII complex, 3. EPR spectroscopy suggested the oxidation was borne principally by the central metal atom, yielding a low-spin d7 NiIII ion, sitting in a square planar coordination environment. XAS analysis provided further support for this indicating that 3 contained a NiIII center coordinated by four N/O donor ligands. DFT calculations on the structure and Mulliken spin density supported these experimental conclusions further. 3 was capable of oxidizing organic substrates including acetone, DTBP, BNAH, and PPh3. This constitutes the first example of a terminal NiIII-O(X) species that is sufficiently well-behaved to allow thorough structural, spectroscopic, and reactivity investigations. This is an important step towards the elucidation of the properties of these compounds and their role in oxidation catalysis.

Experimental Section

1 was prepared according to the reported procedure[15a] and recrystallized from DMF/diethyl ether. Solutions of 2 were obtained by exposing 1 to CO2 according to the reported procedures[15a], and they were either used directly or the compound was isolated by crystallisation. Deutero-2,6-ditertbutylphenol was prepared according to a modification of the reported literature procedure (See supporting information).[29]

Preparation of 3

A 0.4 mM solution of 2 in acetone was cooled in a cuvette cooled to −80 °C. 52 μL of a freshly prepared 15 M solution of magic blue in acetonitrile was added under continuous stirring. The formation of 3 was immediate as evidenced by the formation of bands at 520 and 790 nm.

General procedure for reactivity experiments

A solution of 3 at −80 °C (or −40 °C) was prepared according to the above procedure. Substrates were added as concentrated acetone solutions. The reactions were monitored using UV-vis spectroscopy, and after complete disappearance of the features corresponding to 3, were allowed to warm up to room temperature. The reaction mixtures were diluted with methanol for MS analysis, or the solvent was removed in vacuo for NMR analysis.

Rate constants determination

Reactions were executed with 7 to 300 equivalents of substrate to ensure pseudo-first order conditions. The second-order rate constant (k2) was determined from the linear dependence of the pseudo-first order constant (kobs) on substrate concentration. Values for the observed kobs were obtained by fitting the decay of the absorbance at 520 nm during a reaction as an exponential. The average from repeated experiments were utilized for the determination of k2.

Additional experimental, spectroscopic, and computational information is included in the supporting information file. This includes [D6]acetone NMRs of 1 and 2, EPR and XAS methods and data analysis, DFT methods and optimised-structures coordinates, spectra and kinetic data for the reactivity studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This publication has emanated from research supported in part by the European Union (FP7-333948, AMcD), a research grant from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI/12/RC/2278, AMcD), and COST Action CM1305 (ECOSTBio). MS acknowledges MINECO (CTQ2011-25086/BQU), DIUE of the Generalitat de Catalunya (2014SGR1202), MICINN (Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain), the FEDER fund (UNGI08-4E-003) and CESCA. Operation of NSLS X3B is supported by NIH grant P30-EB-009998. The NSLS is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886.

References

- [1].a) Sono M, Roach MP, Coulter ED, Dawson JH. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2841–2888. doi: 10.1021/cr9500500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2253–2277. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Solomon EI, Brunold TC, Davis MI, Kemsley JN, Lee S-K, Lehnert N, Neese F, Skulan AJ, Yang Y-S, Zhou J. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:235–350. doi: 10.1021/cr9900275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Solomon EI, Heppner DE, Johnston EM, Ginsbach JW, Cirera J, Qayyum M, Kieber-Emmons MT, Kjaergaard CH, Hadt RG, Tian L. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:3659–3853. doi: 10.1021/cr400327t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Yano J, Yachandra V. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4175–4205. doi: 10.1021/cr4004874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Punniyamurthy T, Velusamy S, Iqbal J. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2329–2363. doi: 10.1021/cr050523v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Singh A, Spiccia L. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:2607–2622. [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Nam W. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:522–531. doi: 10.1021/ar700027f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Krebs C, Galonić Fujimori D, Walsh CT, Bollinger JM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:484–492. doi: 10.1021/ar700066p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Que L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:493–500. doi: 10.1021/ar700024g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yin G. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010;254:1826–1842. [Google Scholar]; e McDonald AR, Que L. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:414–428. [Google Scholar]; f Song WJ, Seo MS, George SD, Ohta T, Song R, Kang M-J, Tosha T, Kitagawa T, Solomon EI, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1268–1277. doi: 10.1021/ja066460v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Wu X, Seo MS, Davis KM, Lee Y-M, Chen J, Cho K-B, Pushkar YN, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:20088–20091. doi: 10.1021/ja208523u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Taguchi T, Gupta R, Lassalle-Kaiser B, Boyce DW, Yachandra VK, Tolman WB, Yano J, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1996–1999. doi: 10.1021/ja210957u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Pfaff FF, Kundu S, Risch M, Pandian S, Heims F, Pryjomska-Ray I, Haack P, Metzinger R, Bill E, Dau H, Comba P, Ray K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:1711–1715. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005869. Angew. Chem. 2011, 143, 1749-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hong S, Pfaff FF, Kwon E, Wang Y, Seo M-S, Bill E, Ray K, Nam W. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:10493–10407. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405874. Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 10571-10575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Donoghue PJ, Tehranchi J, Cramer CJ, Sarangi R, Solomon EI, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17602–17605. doi: 10.1021/ja207882h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Koola JD, Kochi JK. Inorg. Chem. 1987;26:908–916. [Google Scholar]; b Irie R, Ito Y, Katsuki T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:6891–6894. [Google Scholar]; c Yamada T, Takai T, Rhode O, Mukaiyama T. Chem. Lett. 1991;20:1–4. [Google Scholar]; d Kureshy RI, Khan NH, Abdi SHR, Iyer P, Bhatt AK. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 1998;130:41–50. [Google Scholar]; e Fernández I, Pedro J, Rosello AL, Ruiz R, Ottenwaelder X, Journaux Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2869–2872. [Google Scholar]; f Nagataki T, Tachi Y, Itoh S. Chem. Commun. 2006;14:4016–4018. doi: 10.1039/b608311k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Nagataki T, Itoh S. Chem. Lett. 2007;36:748–749. [Google Scholar]; h Nagataki T, Ishii K, Tachi Y, Itoh S. Dalton Trans. 2007;21:1120–1128. doi: 10.1039/b615503k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Balamurugan M, Mayilmurugan R, Suresh E, Palaniandavar M. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:9413–9424. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10902b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Sankaralingam M, Vadivelu P, Suresh E, Palaniandavar M. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2013;407:98–107. [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Zhu G, Glass EN, Zhao C, Lv H, Vickers JW, Geletii YV, Musaev DG, Song J, Hill CL. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:13043–13049. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30331k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang M, Zhang M-T, Hou C, Ke Z-F, Lu T-B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:13042–13048. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406983. Angew. Chem., 126, 13258-13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Chen G, Chen L, Ng S-M, Lau T-C. ChemSusChem. 2014;7:127–134. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201300561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Singh A, Chang SLY, Hocking RK, Bach U, Spiccia L. Catal. Sci. Tech. 2013;3:1725–1732. [Google Scholar]; c Hong D, Yamada Y, Nagatomi T, Takai Y, Fukuzumi S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19572–19575. doi: 10.1021/ja309771h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Dincă M, Surendranath Y, Nocera DG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:10337–10341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001859107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Boizumault-Moriceau P. Appl. Cat., A. 2003;245:55–67. [Google Scholar]; f Zhang X, Liu J, Jing Y, Xie Y. Appl. Cat., A. 2003;240:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Sankaralingam M, Balamurugan M, Palaniandavar M, Vadivelu P, Suresh CH. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:11346–11361. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kinneary JF, Albert JS, Burrows CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:6124–6129. doi: 10.1021/ja00226a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yoon H, Wagler TR, O'Connor KJ, Burrows CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4568–4570. [Google Scholar]; d Bediako DK, Surendranath Y, Nocera DG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3662–3674. doi: 10.1021/ja3126432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pierpont AW, Cundari TR. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:2038–2046. doi: 10.1021/ic901250z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pfaff FF, Heims F, Kundu S, Mebs S, Ray K. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:3730–3732. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30716b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chmielewski PJ, Latos-Grażyński L. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:840–845. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chiou T.-w., Liaw W.-f. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:7908–7913. doi: 10.1021/ic801069t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Shiren K, Ogo S, Fujinami S, Hayashi H, Suzuki M, Uehara A, Watanabe Y, Moro-oka Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:254–262. [Google Scholar]; b Itoh S, Bandoh H, Nakagawa M, Nagatomo S, Kitagawa T, Karlin KD, Fukuzumi S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11168–11178. doi: 10.1021/ja0104094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hikichi S, Yoshizawa M, Sasakura Y, Komatsuzaki H, Moro-oka Y, Akita M. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:5011–5028. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20011203)7:23<5011::aid-chem5011>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Itoh S, Bandoh H, Nagatomo S, Kitagawa T, Fukuzumi S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:8945–8946. doi: 10.1021/ja0104094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Schenker R, Mandimutsira BS, Riordan CG, Brunold TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:13842–13855. doi: 10.1021/ja027049k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Fujita K, Schenker R, Gu W, Brunold TC, Cramer SP, Riordan CG. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:3324–3326. doi: 10.1021/ic049876n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kundu S, Pfaff FF, Miceli E, Zaharieva I, Herwig C, Yao S, Farquhar ER, Kuhlmann U, Bill E, Hildebrandt P, Dau H, Driess M, Limberg C, Ray K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013;52:5622–5626. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300861. Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 5732-5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Huang D, Holm RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4693–4701. doi: 10.1021/ja1003125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Huang D, Makhlynets OV, Tan LL, Lee SC, Rybak-Akimova EV, Holm RH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:1222–1227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017430108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Huang D, Makhlynets OV, Tan LL, Lee SC, Rybak-Akimova EV, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:10070–10081. doi: 10.1021/ic200942u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Troeppner O, Huang D, Holm RH, Ivanović-Burmazović I. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:5274–5279. doi: 10.1039/c3dt53004c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Patra AK, Mukherjee R. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1388–1393. [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Donoghue PJ, Gupta AK, Boyce DW, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15869–15871. doi: 10.1021/ja106244k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pirovano P, Magherusan AM, McGlynn C, Ure A, Lynes A, McDonald AR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014:5946–5950. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311152. Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 6056-6060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Halvagar MR, Solntsev PV, Lim H, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI, Cramer CJ, Tolman WB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:7269–7272. doi: 10.1021/ja503629r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bell FA, Ledwith A, Sherrington DC. J. Chem. Soc. C. 1969:2719–2720. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Connelly NG, Geiger WE. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:877–910. doi: 10.1021/cr940053x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Lappin AG, Laranjeira MCM, Peacock RD. Inorg. Chem. 1983;22:786–791. [Google Scholar]; b Jacobs SA, Margerum DW. Inorg. Chem. 1984;23:1195–1201. [Google Scholar]; c Kruger HJ, Holm RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2955–2963. [Google Scholar]; d Kruger HJ, Peng G, Holm RH. Inorg. Chem. 1991;30:734–742. [Google Scholar]; e Corker JM, Evans J, Levason W, Spicer MD, Andrews P. Inorg. Chem. 1991;30:331–334. [Google Scholar]; f Storr T, Verma P, Shimazaki Y, Wasinger EC, Stack TDP. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:8980–8983. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Lee Y-M, Hong S, Morimoto Y, Shin W, Fukuzumi S, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10668–10670. doi: 10.1021/ja103903c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Cao T-P-A, Nocton G, Ricard L, Le Goff XF, Auffrant A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:1368–1372. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309222. Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 1192-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Lovecchio FV, Gore ES, Busch DH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:3109–3118. [Google Scholar]; b Haines RI, McAuley A. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1981;39:77–119. [Google Scholar]; c Stuart JN, Goerges AL, Zaleski JM. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:5976–5984. doi: 10.1021/ic000572k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Haines RI, Mcauley A. Inorg. Chem. 1980;1109:719–723. [Google Scholar]; b Alonso PJ, Falvello LR, Forniés J, Martín A, Menjón B, Rodríguez G. Chem. Commun. 1997;2:503–504. [Google Scholar]; c Collins TJ, Nichols TR, Uffelman ES. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4708–4709. [Google Scholar]; d Ottenwaelder X, Ruiz-García R, Blondin G, Carasco R, Cano J, Lexa D, Journaux Y, Aukauloo A. Chem. Commun. 2004:504–505. doi: 10.1039/b312295f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Colpas GJ, Maroney MJ, Bagyinka C, Kumar M, Willis WS, Suib SL, Mascharak PK, Baidya N. Inorg. Chem. 1991;30:920–928. [Google Scholar]; b Cho J, Kang HY, Liu LV, Sarangi R, Solomon EI, Nam W. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:1502–1508. doi: 10.1039/C3SC22173C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].a) Haumann M, Porthun A, Buhrke T, Liebisch P, Meyer-Klaucke W, Friedrich B, Dau H. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11004–11015. doi: 10.1021/bi034804d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Davidson G, Choudhury SB, Gu Z, Bose K, Roseboom W, Albracht SPJ, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7468–7479. doi: 10.1021/bi000300t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sarangi R. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:459–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schaefer T, Schindelka J, Hoffmann D, Herrmann H. J Phys. Chem. A. 2012;116:6317–6326. doi: 10.1021/jp2120753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Alnajjar MS, Zhang X-M, Gleicher GJ, Truksa SV, Franz JA. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67(25):9016–9022. doi: 10.1021/jo020275s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Altwicker ER. Chem. Rev. 1967;67:475–531. [Google Scholar]; b Wittman JM, Hayoun R, Kaminsky W, Coggins MK, Mayer JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12956–12959. doi: 10.1021/ja406500h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sastri CV, Park MJ, Ohta T, Jackson TA, Stubna A, Seo MS, Lee J, Kim J, Kitagawa T, Münck E, Que L, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12494–12495. doi: 10.1021/ja0540573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kurahashi T, Kikuchi A, Shiro Y, Hada M, Fujii H. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:6664–6672. doi: 10.1021/ic100673b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.