Abstract

Objectives

Historically, the nature of association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and gouty arthritis has been unclear. The goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that CKD is an independent risk factor for developing incident gout.

Design

Patients were from the original Framingham Heart Study cohort. Using Cox proportional hazard models we estimated the HR of CKD to incident gout among men and women separately after adjusting for age, alcohol consumption, smoking, hypertension, diabetes and body mass index.

Settings

Patients were all from Framingham, Massachusetts, USA.

Participants

Excluding patients who had CKD in the first visit from this study, 2159 men and 2558 women were selected covering a 54-year period (1948–2002).

Results

There were 371 incident cases (231 men and 140 women) of gout over the follow-up of 140 421 person-years. Incidence rates of gout per 1000 person-years for participants with and without CKD were 6.82 (95% CI 5.10 to 9.10) and 2.43 (2.18 to 2.71), respectively. In multivariable Cox models, CKD was associated with gout, with a HR of 1.88 (1.13 to 3.13) among men and 2.31 (1.25 to 4.24) among women. Additional analyses using alternate definitions for CKD and cross-sectional study did not change the results. Sensitivity analysis suggested that the observed findings might be an underestimate of the true relative risk.

Conclusions

The present study provides epidemiological evidence to support the notion that CKD is a risk factor for gout.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an independent risk factor for incident gout.

The association of CKD to gout is more remarkable in men than that in women.

Sensitivity analysis suggested that the association between CKD and incident gout can be stronger than our observations.

Limitations of this study include the fact that serum uric acid levels in the original Framingham Heart Study cohort were not consistently measured; the definitions of gout and CKD both included self-reported data.

Introduction

Gout or gouty arthritis is a common and painful inflammatory arthritis characterised by deposition of monosodium urate crystals in joint fluid and articular tissue.1 Gout affected over 7.5 million Americans during 2009–2010,2 3 including 1.25 million men and 0.78 million women with moderate or severe renal impairment.3 The probability of gout can arise depending not only on urate load but also on other risk factors1 such as older age, obesity, male sex, female menopause, hyperuricaemia, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), excessive purine-rich diet and excessive alcohol consumption.4 5

Urate, a byproduct of purine catabolism, is primarily excreted by the kidneys through an active, energy-dependent process. Any impairment in renal urate clearance first leads to compensatory increase in gastrointestinal tract urate clearance. When gastrointestinal urate clearance is insufficient to maintain total body urate excretion, serum urate then increases, thereby increasing the risk for gout.6 7 Furthermore, it is possible that kidney disease can lead to gout through mechanisms other than hyperuricaemia, as variations in serum urate are insufficient to explain most of the risk associated with CKD.8 Yet, there have been relatively few prospective studies examining the CKD–gout link. Most studies examined the prevalence and incidence of CKD among gout cases or the incidence among those with end-stage renal disease.3 8–14 Recently, we published data from the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT), which showed that among middle aged men, reduced glomerular filtration rate as well as urinary abnormalities were risk factors for gout independent of serum urate concentrations.15 However, the MRFIT was of relatively short duration and included only men with high prevalence of metabolic syndrome. The goal of the present study was to assess the role of CKD as an independent risk factor for developing incident gout among men and women in a community-based cohort over longer periods of follow-up.

Methods

Study population and observation period

We conducted a cohort study on the original Framingham Heart Study (FHS) cohort, using the limited-access data obtained from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The FHS is an ongoing longitudinal study of 5209 men and women from the town of Framingham, Massachusetts, who were 29–62 years old at the time of recruitment in 1948. Participants have been followed up biennially. At each study, examination data from detailed medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests were collected. Additional details of the FHS cohort are described elsewhere.16 We limited our analyses to 2159 men and 2558 women, who were free of both gout and CKD at their first assessment. We used the data for 26 study examinations (1–26) during a 54-year period (1948–2002).

Ascertainment of gout, CKD and covariates

For the primary analyses, we excluded patients with a diagnosis of CKD or gout at the baseline visit.

Unless specified otherwise, all the definitions were based on the original FHS protocols. Specifically, gout (the outcome) was defined as the presence of any of the following: FHS study physician-diagnosed gout, usage of any gout medication (allopurinol, probenecid and colchicine), self-reported gout or presence of individual gout history, or radiographic changes suggestive of gouty arthritis. FHS study physician-diagnosed gout was identified according to the following criteria: if the participant had experienced acute joint pain, accompanied by swelling and heat, lasting from a few days to 2 weeks, and followed by complete remission of symptoms.17 Renal function was assessed by serum creatinine measurement and calculation of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) according to the abbreviated equation in modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) study: GFR=186.3×(serum creatinine)−1.154×age−0.203×(0.742 for women).18 Owing to the large amount of missing values on creatinine level, calculations of eGFR were available only in five visits and could not be a global criteria for defining CKD as the main exposure. Therefore, CKD was defined as FHS physician-diagnosed CKD or presence of CKD by self-report. To test the validity of this case definition, we checked the creatinine level against CKD diagnostic in the visits where both had available data (visits 15, 25, 26). The mean (with SD) value of creatinine (mg/dL) for patients with CKD was 1.59 (1.04) versus patients without CKD 1.25 (0.27) in men (p<0.001) and 1.29 (0.64) vs 1.08 (0.26) in women (p<0.001). This corresponds to an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR, in mL/min/1.73 m2) 59.17 (SD=26.75) vs 64.54 (SD=19.40) in men (p=0.004) and 52.56 (22.15) vs 57.23 (18.53) in women (p=0.008). The eGFRs suggest that the definition of CKD in this study was similar to a number of other studies.19–21

Hypertension was defined as occurrence of any of the following: systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg or current use of antihypertensive medications.22 Alcohol consumption and smoking were derived from self-report, defined as any usage of any alcohol and any tobacco, respectively. Patients’ sex, age, body mass index (BMI), serum urate (serum uric acid, SUA) level and plasma lipid concentration were obtained from Framingham raw data. Diabetes was defined according to FHS official review. Specifically, diabetes was deemed to be present if a patient's blood glucose level was above 200 mg/dL, or if a patient was currently under treatment for diabetes.23 SUA was measured only at examination numbers 1, 2, 3, 4 and 13. As SUA values may vary based on development of CKD, as explained in the introduction, use of imputed values of SUA was not deemed suitable for the objective of this study and hence not included in the primary analysis.

Statistical analysis

Any individual classified as having gout, kidney disease, diabetes or hypertension, was assumed to have the diagnosis throughout the remaining part of follow-up. Sex, alcohol consumption, smoking, diabetes and hypertension were analysed as dichotomous variables. Age, BMI, plasma lipid concentration and SUA level were analysed as continuous variables. The key independent variable was presence or absence of CKD.

Primary analyses were performed using time-to-event Kaplan-Meier methods for incident gout. Here, the observation for participants in the CKD group started from the date of the visit when the CKD was incident and ended at the date of incident gout, last study visit, or death, whichever was the earliest. Accordingly, these analyses excluded those participants who had a diagnosis of CKD or gout at the first study visit. For the non-CKD group, the observation time was computed from the baseline visit to the earliest of: date of incident gout, last study visit, death or incidence of CKD.

We calculated incident rates (per 1000 person-years) for CKD and non-CKD groups, stratified by gender. We also used Cox proportional hazards model with time-varying covariates to estimate the HR of incident gout associated with CKD. In these regressions, the time-varying covariates such as age and BMI were updated at each observation. Men and women were analysed separately prior to combining their data. Variables not significant in bi-variable models (eg, plasma lipids) were excluded in the multivariable models. Multivariable models were adjusted for the following known risk factors in a time-dependent manner: sex, age, BMI, alcohol consumption, smoking, diabetes and hypertension, plus an option of with or without SUA.

In the primary analyses, we examined the risk for incident gout in relationship to incident CKD; additional analyses included those participants with CKD at baseline as well. Moreover, the statistical role of SUA on the CKD–gout association was cross-sectionally examined employing logistic regression models using data from visit 4 as SUA was not consistently measured in all the study visits.

We performed probabilistic sensitivity tests24 to examine the impact of potential misclassification of gout, selection bias and unmeasured confounding factors. We set the assumptions of misclassifications to range from 10% to 70%, relative risk of unmeasured confounders to range from 0.3 to 4.2 and selection bias parameter 0.6–3.0, and simulated 20 000 replications. After the analysis, frequency distribution of bias, error adjusted ORs and changes in the magnitude adjusted ORs (in response to changes in magnitude and direction of bias) were examined.

All p values were two sided. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA (V.12.1).

Results

Baseline characteristics

After the exclusion of patients with CKD at the baseline, only the participants who were free of CKD at baseline were considered for this analysis. The baseline characteristics of the FHS cohort included in this study, according to CKD status at the end of the study (instead of the baseline), are shown in table 1. The cohort was comprised of 2159 men and 2558 women.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the original Framingham Heart Study cohort

| Baseline characteristics | Overall (n=4717)* | No CKD (n=4251) | CKD (n=464) | p Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (%) | 54 | 54 | 53 | 0.46 |

| Age (years) | 45 | 45 | 42 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6 | 25.6 | 25.4 | 0.16 |

| Ever smokers (%) | 63 | 64 | 60 | 0.07 |

| Diabetes (%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.74 |

| Hypertension (%) | 40 | 41 | 31 | <0.001 |

| Total plasma cholesterol (mg/dL) | 221.5 | 221.9 | 218.0 | 0.18 |

| Serum urate (mg/dL) | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 0.85 |

The table is stratified by CKD status at the end of the study.

*There were two patients with missing values on CKD status throughout the study.

†p Value is for unpaired Student t test for no CKD vs CKD groups.

BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Incidence rates

A total of 464 individuals (220 men and 244 women) developed incident CKD during the follow-up until examination 26. For the entire cohort, there were 371 incident cases (231 men and 140 women) of gout over the total follow-up of 140 421 person-years. The median follow-up time was 36 years (IQR 26–47 years). The overall incidence rate of gout was 2.64 (95% CI 2.39 to 2.93) per 1000 person-years. The rates among men and women were 3.89 (95% CI 3.42 to 4.43) and 1.73 (95% CI 1.46 to 2.04), respectively.

Gout incidence among participants with and without CKD

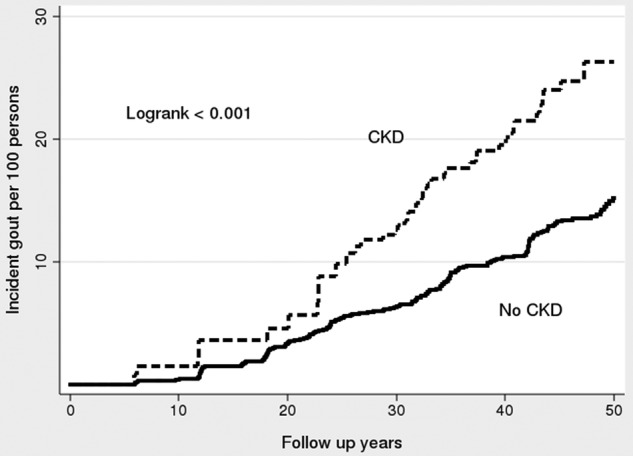

The incidence rate of gout was 6.82 (95% CI 5.10 to 9.10) per 1000 person-years among those with CKD and 2.43 (95% CI 2.18 to 2.71) among those without. Table 2 shows the incidence rates stratified by gender. The incidence rate in the CKD group for men was 10.24 (95% CI 7.02 to 14.93) and for women was 4.62 (95% CI 2.95 to 7.24). There were relatively few cases of gout in the first 20 years of follow-up. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier failure estimates for gout.

Table 2.

Incidence rates for gout according to chronic kidney disease (CKD) status in the original Framingham Heart Study cohort

| Men |

Women |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incident gout | Rate (95% CI) | Incident gout | Rate (95% CI) | |

| No CKD | 204 | 3.60 (3.13 to 4.12) | 121 | 1.57 (1.32 to 1.88) |

| CKD | 27 | 10.24 (7.02 to 14.93) | 19 | 4.62 (2.95 to 7.24) |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier failure estimates for incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) to incident gout among participants who developed incident CKD after the baseline visit and those who never developed CKD in the original Framingham Heart Study cohort.

In unadjusted Cox regression models, CKD was associated with an increased risk of gout with an HR of 2.04 (95% CI 1.48 to 2.80). In multivariable regression models (adjusted for age, sex, BMI, alcohol use, smoking, hypertension and diabetes), CKD was associated with an HR of 2.09 (95% CI 1.41 to 3.08) for incident gout overall, and was similar when men and women were examined separately (table 3). We performed a further test by adding a menopause variable to the multivariable regression for women. However, the HR did not change materially—from 2.31 (table 3) to 2.28 (data not shown).

Table 3.

HRs: non-prevalent chronic kidney disease (CKD) to incident gout in the original Framingham Heart Study cohort

| HR (95% CI)* | Overall | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | 2.04 (1.48 to 2.80) | 2.07 (1.37 to 3.14) | 1.95 (1.19 to 3.22) |

| Age adjusted | 2.04 (1.48 to 2.80) | 2.10 (1.38 to 3.18) | 1.95 (1.19 to 3.22) |

| Age–sex adjusted | 2.05 (1.49 to 2.82) | ||

| Multivariable† | 2.09 (1.41 to 3.08) | 1.88 (1.13 to 3.13) | 2.31 (1.25 to 4.24) |

*All the results were statistically significant (p<0.05).

†Multivariable HRs were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, alcohol use, smoking, hypertension and diabetes.

Additional analyses

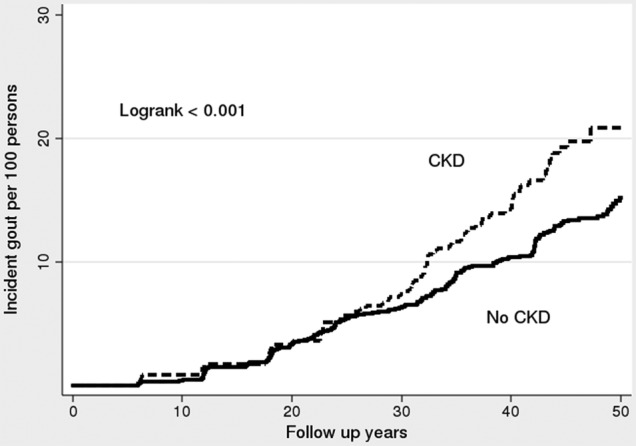

We performed additional analyses to assess the influence of prevalent CKD (combined with incident CKD altogether to be the new main exposure) on gout (the same outcome). For this purpose, we further included 347 participants with prevalent CKD at baseline, who were excluded from the main analyses. In these analyses there were 399 incident cases (249 men and 150 women) of gout and the overall incidence rate of gout was 2.64 (95% CI 2.39 to 2.91) per 1000 person-years. There were 811 individuals (340 men and 471 women) with CKD in general; the incidence rate of gout was 4.26 (95% CI 3.39 to 5.35) per 1000 person-years among those with CKD in general and 2.43 (95% CI 2.18 to 2.71) among those without. The Kaplan-Meier failure estimates for this analysis are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier failure estimates for gout, among participants who had chronic kidney disease (CKD; including CKD present in baseline) and those who never developed CKD in the original Framingham Heart Study cohort.

In unadjusted Cox regression models, CKD in general was also associated with an increased risk of gout with an HR of 1.47 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.90); in the multivariable Cox models identical to those used in the main analyses, CKD in general was associated with HR of 1.61 (95% CI 1.17 to 2.21) to incident gout (see online supplementary table S1).

Moreover, we performed a cross-sectional analysis for influence of SUA on the relationship between CKD and gout. As aforementioned, since SUA data are only available in five visits (visits 1–4 and 13), we chose to perform a logistic regression on visit 4 because it was the last visit of the continuous four visits. In the multivariable logistic regression, SUA was included in an additional test besides other covariates as aforementioned; in this additional test, the ORs for CKD (as shown in online supplementary table S2) and SUA (data not shown) were 1.82 (1.13 to 2.93) and 3.35 (2.73 to 4.11) for men, 0.81 (0.44 to 1.46) and 1.97 (1.56 to 2.49) for women, and 1.27 (0.89 to 1.82) and 2.66 (2.30 to 3.09) overall. Comparisons have been made between unadjusted and SUA adjusted ORs as well as multivariable ORs with or without SUA in the model. In both comparisons, the results did not differ materially, as shown in online supplementary table S2.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses for the impact of misclassification, unmeasured confounding and selection bias on the estimated association between CKD and gout are shown in online supplementary figure S1. The frequency distribution of bias and error adjusted ORs are shown in online supplementary figure S1A, where the median bias-adjusted relative risk was 10.47 with 95% simulation ranging from 1.83 and 248. Changes in the magnitude adjusted OR in response to changes in magnitude and direction of bias are shown in online supplementary figure S1B.

Discussion

Our analysis of data collected on the original FHS participants indicates that CKD is an independent risk factor for gout. The analysis suggested that the HR of CKD to gout is approximately 2.0 (non-prevalent CKD) to approximately 1.5 (CKD in general). This result is similar to another study using MRFIT data,8 where the adjusted HR for gout among those with CKD was 1.61 (1.60 to 1.61).

In this prospective study based on 54 years of follow-up data from FHS participants, the risk of gout associated with CKD was doubled (HR=2.09; 95% CI 1.41 to 3.08) in participants free from CKD and gout at baseline. These associations persisted in both sexes, as well as in our additional analyses including those with CKD at baseline, and were independent of other known risk factors of gout, including age, BMI, alcohol use, smoking, hypertension and diabetes. Overall, these findings provide prospective evidence that individuals with CKD are at an increased future risk of gout independent of other known risk factors. Our sensitivity analyses indicated that even after assuming extreme and unlikely degrees of misclassification and bias, the relative risk estimate is about 1.8, suggesting that the true relative risk might be stronger.

Historically, the impact of CKD on gout has been debated,1 25 26 as different studies observed different results. One factor that was often involved in the debates is SUA. However, not all patients with hyperuricaemia develop gout, and the reasons remain unclear.27 28 Furthermore, it is difficult to ascertain if hyperuricaemia preceded CKD or whether the reverse is true.25 To test the influence of SUA with the relationship between CKD and gout, we performed a cross-sectional study. The results suggested that although an increased SUA level was associated with the risk of gout, CKD is still associated with incident gout. However, we noticed that in this cross-sectional study, CKD was associated with a decreased risk of gout in women; this was because in this specific visit (visit 4) no woman had gout among 303 women with CKD.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the study spans five decades, and data collection and measurement are unlikely to be uniform. The severity and duration of CKD was not available in the FHS data set. The number of participants decreased during the follow-ups so survival bias is possible. Additionally, as aforementioned, SUA levels were measured only in five visits; therefore, we assessed the role of SUA in an additional analysis. We are also aware that some studies10 hypothesised that lead (Pb2+) may be one unifying cause or risk factor for both CKD and gout, however, this information is not available in FHS and further investigation is still needed. Lastly, similar to many survey-based studies,1 25 26 the definitions of gout and CKD both included self-reported data. However, it must be noted that this study was performed using community-based data from the FHS, and thus the findings may be generalisable to the US population. However, the data set was large and cases were numerous enough for meaningful analyses. This is also the longest follow-up study, to the best of our knowledge, in terms of assessing the relationship between CKD and gout.

In summary, these prospective data from the FHS provide the empiric basis that CKD is a risk factor for gout and the temporality of association documented here points towards the underlying causal nature.

Footnotes

Contributors: WW was the primary author running the statistical tests and writing this article. VMB offered extensive constructive suggestions. EK critically revised the article and provided fundamental guidelines.

Funding: The FHS was conducted and supported by the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the Framingham Heart Study investigators. The analyses performed in this study utilized a limited access dataset made available by the NHLBI. The analyses presented in this manuscript did not receive any extramural funding.

Competing interests: EK has received grant funding and has served as a consultant to the following: Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Ardea Pharmaceuticals and Metabolex, Inc.

Ethics approval: Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data used for this study were made available from the US NHLBI through a limited access programme after presenting an acceptable analysis plan and getting IRB approval. Any person who requires it can gain access to the data by following the procedure described in https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/.

References

- 1.Clive DM. Renal transplant-associated hyperuricemia and gout. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000;11:974–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnan E, Lienesch D, Kwoh CK. Gout in ambulatory care settings in the United States. J Rheumatol 2008;35:498–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnan E. Reduced glomerular function and prevalence of gout: NHANES 2009–10. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e50046 10.1371/journal.pone.0050046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C et al. . SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout. Nat Genet 2008;40:437–42. 10.1038/ng.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saag KG, Mikuls TR. Recent advances in the epidemiology of gout. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2005;7:235–41. 10.1007/s11926-996-0045-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorensen LB, Levinson DJ. Origin and extrarenal elimination of uric acid in man. Nephron 1975;14:7–20. 10.1159/000180432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieselbach RE, Sorensen LB, Shelp WD et al. . Diminished renal urate secretion per nephron as a basis for primary gout. Ann Intern Med 1970;73:359–66. 10.7326/0003-4819-73-3-359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan E. Chronic kidney disease and the risk of incident gout among middle-aged men: a seven-year prospective observational study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:3271–8. 10.1002/art.38171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Talbott JH, Terplan KL. The kidney in gout. Medicine 1960;39:405–67. 10.1097/00005792-196012000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorensen LF. Gout secondary to chronic renal disease: studies on urate metabolism. Ann Rheum Dis 1980;39:424–30. 10.1136/ard.39.5.424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnan E, Akhras KS, Sharma H et al. . Serum urate and incidence of kidney disease among veterans with gout. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1166–72. 10.3899/jrheum.121061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuldeore MJ, Riedel AA, Zarotsky V et al. . Chronic kidney disease in gout in a managed care setting. BMC Nephrol 2011;12:36 10.1186/1471-2369-12-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avram Z, Krishnan E. Hyperuricaemia—where nephrology meets rheumatology. Rheumatology 2008;47:960–4. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Miller ER III et al. . Association of kidney disease with prevalent gout in the United States in 1988–1994 and 2007–2010. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;42:551–61. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnan E, Kwoh CK, Schumacher HR et al. . Hyperuricemia and incidence of hypertension among men without metabolic syndrome. Hypertension 2007;49:298–303. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000254480.64564.b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE Jr. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease: the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health 1951;41:279–81. 10.2105/AJPH.41.3.279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbott RD, Brand FN, Kannel WB et al. . Gout and coronary heart disease: the Framingham Study. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:237–42. 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90127-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E et al. . National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:137–47. 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh NI, Hwang SJ, Larson MG et al. . Chronic kidney disease as a predictor of cardiovascular disease (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2008;102:47–53. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF et al. . The Framingham predictive instrument in chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:217–24. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox CS, Larson MG, Leip EP et al. . Glycemic status and development of kidney disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2436–40. 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.[No authors listed] The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:2413–46. 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440420033005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preis SR, Hwang SJ, Coady S et al. . Trends in all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among women and men with and without diabetes mellitus in the Framingham Heart Study, 1950 to 2005. Circulation 2009;119:1728–35. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.829176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenland S. Basic methods for sensitivity analysis of biases. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:1107–16. 10.1093/ije/25.6.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teng GG, Ang LW, Saag KG et al. . Mortality due to coronary heart disease and kidney disease among middle-aged and elderly men and women with gout in the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:924–8. 10.1136/ard.2011.200523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomita M, Mizuno S, Yamanaka H et al. . Does hyperuricemia affect mortality? A prospective cohort study of Japanese male workers. J Epidemiol 2000;10:403–9. 10.2188/jea.10.403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stamp L, Ha L, Searle M et al. . Gout in renal transplant recipients. Nephrology 2006;11:367–71. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards NL. The role of hyperuricemia and gout in kidney and cardiovascular disease. Cleve Clin J Med 2008;75(Suppl 5): S13–16. 10.3949/ccjm.75.Suppl_5.S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]