Abstract

Objective

To determine factors and outcomes associated with ultra-early surgery for poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (aSAH).

Design

A multicentre retrospective analysis, observational study.

Setting

High-volume teaching hospitals (more than 150 aSAH cases per year).

Participants

118 patients with World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) grades IV and V underwent surgical treatment. Ultra-early surgery was defined as surgery performed within 24 h of aSAH, and delayed surgery as surgery performed after 24 h. Outcome was assessed by modified Rankin Scale (mRS). The mean time of follow-up was 12.5±3.4 months (range 6–28 months).

Results

47 (40%) patients underwent ultra-early surgery, and 71 (60%) patients underwent delayed surgery. Patients with WFNS grade V (p=0.011) and brain herniation (p=0.004) more often underwent ultra-early surgery. Postoperative complications were similar in ultra-early and delayed surgery groups. Adjusted multivariate analysis showed the outcomes were similar between the two groups. Multivariate analysis of predictors of poor outcome, ultraearly surgery was not an independent predictor of poor outcome, while advanced age, postresuscitation WFNS V grade, intraventricular haemorrhage, brain herniation and non-middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms were associated with poor outcome.

Conclusions

Although patients with WFNS grade V and brain herniation more often undergo ultra-early surgery, postoperative complications and outcomes in selected patients were similar in the two groups. Patients of younger age, WFNS grade IV, absence of intraventricular haemorrhage, absence of brain herniation and MCA aneurysms are more likely to have a good outcome. Ultra-early surgery could improve outcomes in carefully selected patients with poor-grade aSAH.

Keywords: NEUROSURGERY, VASCULAR SURGERY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a relatively large, contemporary cohort of poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage after surgical treatment.

Patients with World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies grade V and brain herniation more often undergo ultra-early surgery. Postoperative complications and outcomes in selected patients were similar between groups.

This study evaluated predictors of poor outcome based on contemporary multicentre cohorts.

The timing of surgery is not randomised, and a retrospective analysis has selection bias.

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (aSAH) is a devastating condition with high morbidity and mortality. Aneurysm rebleeding and cerebral vasospasm are the most important causes of morbidity and mortality.1 2 Poor-grade aSAH has a higher risk of rebleeding and cerebral vasospasm than good-grade aSAH.3–6 In the past decades, several studies have shown that early surgery potentially improves outcomes in selected patients with poor-grade aSAH.6–14 However, this approach is still associated with a high mortality and morbidity.6 9 12 15 16

Recently, ultra-early treatment (within 24 h of ictus) has been reported to reduce the risk of rebleeding and improve outcomes in the majority of patients with good-grade aSAH.17–19 Treatment for aneurysm as early as possible is also recommended to prevent rebleeding after initial aSAH.20 21 However, poor-grade patients often present with worse clinical condition and experience more severe brain swelling than good-grade patients.22 23 In the recent decades, endovascular treatment has provided an available alternative to surgery of poor-grade aSAH.24–29 Current surgical indications may differ from previous studies. However, no study has evaluated factors associated with ultra-early and delayed surgery for poor-grade aSAH in the modern endovascular era.

In this study, we analysed data from contemporary multicentre cohorts of poor-grade aSAH, and we determined factors and outcomes associated with ultra-early surgery compared with delayed surgery.

Methods

This is a multicentre retrospective analysis. All patients were treated in high-volume teaching hospitals (more than 150 aSAH cases per year) with expertise in aneurysm clipping and coiling. This study was approved by the Chinese Ethics Committee of Registering Clinical Trials and the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University.

Patient population

Between October 2010 and March 2012, 109 patients with poor-grade aSAH (World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) grades IV and V) after hospitalisation, who underwent surgical treatment, were included in A Multicenter prospective Poor-grade Aneurysmal Subarachnoid haemorrhage registry Study (AMPAS).30 Between March 2012 and April 2014, 289 patients with aSAH undergoing surgery were included in the database of the China National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases (NCRC-ND), and 35 (12%) consecutive poor-grade patients were identified. Patients were excluded in current databases if they die after resuscitation, or the family withdrew care in the emergency room. In this study, poor-grade patients were included if they were older than 18 years and less than 75 years, presented with WFNS grade IV or V, did not improve after resuscitation, and underwent surgical treatment. Patients were excluded if they experienced neurological deterioration (WFNS grades I–III to IV–V) after hospitalisation, if they underwent aneurysm coiling, if they underwent surgery more than 21 days after aSAH, and if their last follow-up was less than 6 months.

Clinical management

Management protocol included aggressive resuscitation, intensive critical care, early CT angiography or cerebral angiography if possible, early surgery if possible and postoperative intensive care.30 All patients with poor-grade aSAH were resuscitated in the emergency room. After resuscitation, they were assessed by a multidisciplinary team which consisted of vascular neurosurgeons, interventional neuroradiologists and anaesthetists. Treatment options were discussed with the patient’s family or relatives. Surgical selection was based on aneurysm morphology, patient's neurological condition, and treatment-relative risk following multidisciplinary consultation. After surgery, patients were transferred to the intensive care unit, and they underwent standard management for vasospasm.

Data collection

Ultra-early surgery was defined as surgery within 24 h of ictus, and delayed surgery as surgery after 24 h. The time of ictus was defined as the time of loss of consciousness (poor-grade clinical condition). We reviewed the following data: age, sex, history of smoking, medical history, WFNS grade after resuscitation, brain herniation, Fisher grade, intracerebral haematoma (ICH), intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), aneurysm location with size and number, and timing of surgery. Brain herniation was defined as a deterioration of consciousness accompanied by anisocoria or bilateral pupil dilation (excluding oculomotor nerve palsy caused by other diseases). Rebleeding was defined as neurological deterioration with increase in haemorrhage on CT scan.

Outcome measures

Functional outcome was assessed by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Outcome was dichotomised into good (mRS 0–3) and poor outcome (mRS 4–6). No patients were lost to follow-up. The mean time of follow-up was 12.5±3.4 months (range 6–28 months).

Statistical analysis

An independent-sample t test was used for continuous variables, and a χ2 and Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was performed to compare clinical variables between ultra-early and delayed surgery groups. Univariate logistic analysis was performed to determine predictor of poor outcome. Clinical variables with p value <0.1 in univariate analyses were entered into multivariate logistic regression (LR) models. Using the backward LR method, multivariate models were performed to determine factors associated with ultra-early surgery and to identify predictors of poor outcome. Receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (AUC) analysis was used to test the prediction ability. Using the Enter method, the multivariate logistic model was used to assess the effect of ultra-early surgery on outcomes. The adjusted OR and 95% CI were calculated. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS V.22.0 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York, USA). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 144 patients with poor-grade aSAH who underwent surgery, 118 patients were included in the study, and 26 patients were excluded because of neurological deterioration after hospitalisation (from WFNS grades I–III to IV–V) in 23 patients, surgery performed more than 21 days of aSAH in one patient, and last follow-up was less than 6 months in two patients. Demographic and baseline characteristics between ultra-early and delayed surgery groups are shown in table 1. Forty-seven patients (40%) underwent ultra-early surgery, and 71 patients (60%) underwent delayed surgery. The mean age was 54.9±11.5 years (range 19–75 years). The mean size of aneurysm was 6.0±4.0 mm (range 1.0–20 mm).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of ultra-early and delayed surgery groups

| Characteristics | Ultra-early (<24 h) | Delayed (>24 h) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (male/female) | 47 (21/26) | 71 (29/42) | 0.680 |

| Age (mean years±SD) | 53.9 (±12.5) | 55.5 (±10.8) | 0.241 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 9 (19) | 22 (31) | 0.153 |

| Medical history | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 24 (51) | 44 (62) | 0.240 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 6 (13) | 9 (13) | 0.989 |

| Postresuscitation WFNS grade, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| IV | 19 (40) | 52 (73) | |

| V | 28 (60) | 19 (27) | |

| Fisher grade, n (%) | 0.479 | ||

| I–II | 4 (9) | 9 (13) | |

| III–IV | 43 (91) | 62 (89) | |

| Brain herniation, n (%) | 23 (49) | 11 (16) | <0.001 |

| ICH, n (%) | 30 (64) | 28 (40) | 0.010 |

| IVH, n (%) | 16 (34) | 38 (54) | 0.038 |

| Multianeurysms, n (%) | 5 (11) | 15 (21) | 0.137 |

| Aneurysm location, n (%) | 0.344 | ||

| MCA | 24 (51) | 27 (38) | |

| ACoA, ACA | 11 (23) | 24 (34) | |

| ICA, PCoA | 12 (26) | 16 (23) | |

| Posterior circulation | 0 | 3 (4) | |

| Anterior circulation* | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Aneurysm size(mean mm±SD) | 6.0 (±3.9) | 6.3 (±3.6) | 0.706 |

| Rebleeding before surgery, n (%) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 0.966 |

| Improvement before surgery | 2 (4) | 6 (9) | 0.474 |

| In-hospital mortality | 7 (15) | 12 (14) | 0.771 |

| Overall mortality | 15 (32) | 22 (31) | 0.915 |

*Data on location of anterior circulation aneurysm was missing in one patient.

ACA, anterior cerebral artery; ACoA, anterior communicating artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; ICH, intracerebral haematoma; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCoA, posterior communicating artery; WFNS, World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies.

Factors associated with ultra-early surgery

Patient age, sex, smoking, medical history, aneurysm location and size did not differ between the two groups. Ultra-early surgery was more often performed in patients with WFNS grade V (p<0.001), brain herniation (p<0.001), ICH (p=0.010), without IVH (p=0.038; table 1). After adjustment for WFNS grade, brain herniation, ICH and IVH, multivariate analysis showed that WFNS grade V (p=0.011) and brain herniation (p=0.004) were independent factors for ultra-early surgery compared with delayed surgery (table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with ultra-early surgery compared with delayed surgery

| Predictors | Univariate unadjusted |

Multivariate adjusted* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| WFNS grade V | 2.7 (1.3 to 5.8) | 0.010 | 3.0 (1.3 to 7.0) | 0.011 |

| Brain herniation | 5.2 (2.2 to 12.3) | <0.001 | 3.8 (1.5 to 9.6) | 0.004 |

*Adjusted for WFNS grade, brain herniation, intracerebral haematoma and intraventricular haemorrhage.

WFNS, World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies.

Postoperative complications

Major complications during hospitalisation are presented in table 3. Medical complications, including aneurysm rebleeding, symptomatic vasospasm, cerebral infarction, hydrocephalus and meningitis, and pneumonia, did not differ between the two groups.

Table 3.

Postoperative complications between ultra-early and delayed groups

| Complications | Ultra-early (<24 h) | Delayed (>24 h) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aneurysm rebleeding | 2 (4) | 2 (3) | 1.000 |

| Symptomatic vasospasm | 2 (4) | 8 (11) | 0.312 |

| Cerebral infarction | 9 (19) | 13 (18) | 0.909 |

| Hydrocephalus | 4 (9) | 7 (10) | 1.000 |

| Meningitis | 3 (6) | 5 (7) | 1.000 |

| Pneumonia | 22 (47) | 28 (39) | 0.428 |

Outcomes

At a mean 12.5 months of follow-up, 58 (49%) of 118 patients had a good outcome, and overall mortality was observed in 37 (31%). Outcomes in the different timing groups are shown separately in table 4. Of seven patients for the 13–21 days group, four (57%) died. Sixteen (34%) patients in the ultra-early surgery group and 42 (59%) patients in the delayed group had good outcomes. After adjustment for WFNS grade, brain herniation, ICH and IVH, multivariate analysis showed that the outcomes were similar in the two groups (table 5).

Table 4.

Outcomes in the different surgical timing groups

| Outcomes | Total | Ultra-early (<24 h) | 1–7 days | 8–12 days | 13–21 days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRS 0 | 20 (17) | 5 (11) | 13 (25) | 2 (17) | 0 |

| mRS 1 | 20 (17) | 6 (13) | 13 (25) | 1 (8) | 0 |

| mRS 2 | 9 (8) | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 2 (17) | 2 (29) |

| mRS 3 | 9 (8) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 2 (17) | 1 (14) |

| mRS 4–5 | 23 (19) | 16 (34) | 4 (7) | 3 (24) | 0 |

| mRS 6 | 37 (31) | 15 (32) | 16 (31) | 2 (17) | 4 (57) |

mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Table 5.

Outcomes associated with ultra-early surgery compared with delayed surgery

| Outcomes | Univariate unadjusted |

Multivariate adjusted* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Outcome (mRS 0–2) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.8) | 0.014 | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.3) | 0.152 |

| Good (mRS 0–3) | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.8) | 0.008 | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.3) | 0.110 |

| Mortality (mRS 6) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.3) | 0.915 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.8) | 0.435 |

*Adjusted for WFNS grade, brain herniation, intracerebral haematoma and intraventricular haemorrhage.

mRS, modified Rankin Scale; WFNS, World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies.

Predictor of poor outcome

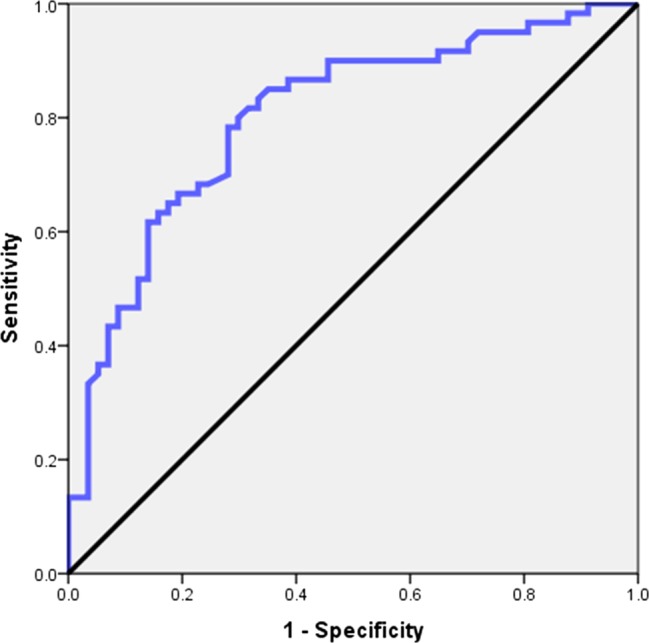

Univariate logistic analysis showed that postresuscitation WFNS grade, Fisher grade, brain herniation, IVH, ultra-early surgery and pneumonia were associated with poor outcome (table 6). Multivariate logistic analysis showed that advanced age (p=0.010), postresuscitation WFNS grade V (p=0.012), brain herniation (p=0.038), IVH (p=0.017) and non-middle cerebral artery (MCA) aneurysms (p=0.028) were independent predictors of poor outcome (table 7). The multivariate model predicted poor outcome with an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.88, p<0.001; figure 1). The timing of surgery was not an independent predictor of poor outcome.

Table 6.

Univariate logistic analysis for predictor of poor outcomes

| Characteristics | Good (mRS 0–3) | Poor (mRS 4–6) | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (male/female) | 58 (26/32) | 60 (24/36) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.7) | 0.596 |

| Age (mean years±SD) | 52.9 (±11.1) | 56.8 (±11.6) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1 | 0.063 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 18 (31) | 13 (22) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.4) | 0.248 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 29 (50) | 39 (65) | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.8) | 0.099 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 7 (12) | 8 (13) | 1.1 (0.4 to 3.3) | 0.894 |

| WFNS grade V, n (%) | 13 (22) | 34 (57) | 4.5 (2.0 to 10.1) | <0.001 |

| Fisher grades III–IV | 48 (83) | 57 (95) | 4.0 (1.0 to 15.2) | 0.034 |

| Brain herniation, n (%) | 9 (16) | 25 (42) | 3.9 (1.6 to 9.3) | 0.002 |

| ICH, n (%) | 26 (45) | 32 (53) | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.9) | 0.356 |

| IVH, n (%) | 21 (36) | 33 (55) | 2.2 (1.0 to 4.5) | 0.025 |

| MCA aneurysm, n (%) | 30 (52) | 21 (35) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.0) | 0.056 |

| Aneurysm size (mean mm±SD) | 6.0 (±3.1) | 6.2 (±4.1) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 0.775 |

| Rebleeding before surgery, n (%) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 2.1 (0.2 to 24.0) | 0.579 |

| Improvement before surgery | 5 (9) | 3 (5) | 0.6 (0.1 to 2.4) | 0.439 |

| Ultra-early surgery | 16 (28) | 31 (52) | 2.8 (1.3 to 6.0) | 0.008 |

| Postoperative complications | ||||

| Aneurysm rebleeding | 0 | 4 (7) | – | 0.99 |

| Symptomatic vasospasm | 4 (7) | 6 (10) | 1.5 (0.4 to 5.6) | 0.547 |

| Cerebral infarction | 7 (12) | 15 (25) | 2.4 (0.9 to 6.5) | 0.077 |

| Hydrocephalus | 4 (7) | 7 (12) | 1.8 (0.5 to 6.4) | 0.378 |

| Meningitis | 2 (3) | 6 (10) | 3.1 (0.6 to 16.1) | 0.176 |

| Pneumonia | 18 (31) | 32 (53) | 2.5 (1.2 to 5.4) | 0.015 |

ICH, intracerebral haematoma; IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; MCA, middle cerebral artery; WFNS, World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies.

Table 7.

Multivariate logistic analysis of predictors of poor outcome

| Predictors | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0.010 |

| Resuscitation WFNS grade V | 3.4 (1.3 to 8.7) | 0.012 |

| Brain herniation | 3.3 (1.1 to 10.1) | 0.038 |

| IVH | 3.1 (1.2 to 7.7) | 0.017 |

| Non-MCA aneurysm | 2.7 (1.1 to 6.9) | 0.028 |

IVH, intraventricular haemorrhage; MCA, middle cerebral artery; WFNS, World Federation of Neurological Societies.

Figure 1.

Graph showing the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of predictive value of poor outcome.

Discussion

In relatively large, multicentre and contemporary cohorts of poor-grade aSAH, 47 (40%) of 118 patients underwent ultra-early surgery. We determined factors and outcomes associated with ultra-early surgery. Patients with WFNS grade V and brain herniation more often underwent ultra-early surgery. However, postoperative complications and outcomes were similar between ultra-early and delayed surgery groups. Additionally, we found patents of younger age, postresuscitation WFNS grade V, absence of brain herniation, absence of IVH, and MCA aneurysms were more likely to have a good outcome. Ultra-early surgery was not associated with outcomes in poor grade aSAH.

In the current era where endovascular treatment is often preferred in poor-grade patients, ultra-early surgery was more often performed in patients with ICH, brain herniation and WFNS grade V. Patients with ICH are in severe clinical condition and undergo ultra-early, even emergency surgery. This finding is similar to the previous studies.6 12 16 31 32 Brain herniation is commonly associated with intracranial mass effect caused by ICH. These patients often experience significant brainstem compression. Ultra-early surgery can reduce increased intracranial pressure and increase cerebral perfusion to improve outcomes especially in these patients. Nevertheless, our study showed that the outcomes were similar between the ultra-early and delayed surgery groups. Multivariate analysis also suggested that ultra-early surgery was not a significant predictor of poor outcome. Our results suggested that ultra-early surgery of selected patients with poor-grade aSAH in a tertiary referral centre is safe.

Timing of surgery for good-grade aSAH has shifted from delayed to early surgery over the past decades. The International Cooperative Study on the Timing of Aneurysm Surgery recruited 3521 patients with aSAH. They found no significant differences of good outcomes between early (0–3 days) and delayed (11–14 days) surgery groups.1 Siddiq et al33 reported that early surgery (within 48 h of admission) was associated with improved outcomes based on the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Recently, Phillips et al17 analysed an 11-year database of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Their study showed that ultra-early treatment was associated with improved outcomes in the majority of good-grade aSAH. However, few studies evaluated outcomes in poor-grade aSAH after ultra-early treatment.6 18 34 Laidlaw and Siu6 34 reported that 40% of patients were independent after 3 months, and that 45% died. Park et al18 reported that ultra-early surgery did not significantly decrease the incidence of rebleeding of poor-grade aSAH. Ultra-early surgery was also not associated with outcomes.13 18 19 Our finding is similar to the earlier studies. The possible reason is that the beneficial effect of ultra-early surgery may be impeded by early brain injury after severe aSAH. Nevertheless, our study also showed that complications were frequent in both groups. Major complications including symptomatic vasospasm, cerebral infarction and hydrocephalus did not differ. These observations may suggest that with modern neuroanaesthesia, improved neurocritical care and microsurgical techniques, ultra-early surgery is not associated with a higher complication rate than delayed surgery.

Outcomes in poor-grade aSAH have been reported in several studies.26 35–37 It is still controversial as to which grading (admission grade or postresuscitation grade) is associated with outcomes.13 24 36 38 We used WFNS grade as initial assessment of aSAH because WFNS grading scale has better interobserver and intraobserver reliability than the Hunt and Hess scale, and makes it more appropriate in different centres.36 A large retrospective study showed that admission WFNS grade V was a predictor of discharge outcome.36 Other studies reported admission poor grade was not associated with outcomes.16 35 39 Patients with admission poor grade may probably improve to good grade after hospitalisation. Admission grading is often influenced by patient sedation during referral from outside the hospital. As expected, our study also showed 8 (7%) patients with poor-grade aSAH improved to good grade. We found that postresuscitation WFNS grade was an independent predictor of poor outcome. Our findings suggest that all patients with admission poor grade should be considered for aggressive resuscitations. Clinical condition after resuscitation needs to be evaluated by the multidisciplinary team. Additionally, our study showed that advanced age was associated with poor outcome. This finding is similar to early studies.35–37 40 IVH was significantly associated with poor outcome. IVH may probably cause irreversible periventricular brain damage.41 Brain herniation at presentation is also associated with poor outcome. We also found that patients with MCA aneurysms were more likely to have a good outcome. This finding may suggest, although endovascular treatment is preferred in poor-grade patients, patients with MCA aneurysms may be considered for surgical treatment.

The primary limitation is that the timing of surgery is not randomised. Many factors, such as delayed referral, logistical factors at the treatment centre, and family decision-making, may affect the timing of surgery. There is a very wide range of timing of delayed surgery. However, multivariate logical models were performed to adjust for potential confounders between the two groups. Second, this is a selection bias in a multicentre retrospective study. Surgical decision was based on multidisciplinary team consultation. Exclusion of untreated patients and selected patients undergoing surgery might lead to a good outcome. Patients with IVH more often underwent delayed surgery, but current databases cannot identify the definitive reasons. However, these data reflected current surgical practice and outcomes of selected patients with poor-grade aSAH in a tertiary referral centre. Additionally, this study mainly focused on factors and outcomes associated with ultra-early surgical treatment. We did not compare outcomes between surgical and endovascular treatment. Further studies on the comparison of outcomes between two different treatment modalities are warranted to determine the effect of ultra-early treatment of poor-grade aSAH. Nevertheless, this knowledge may help to appraise the ultra-early surgery for poor-grade aSAH, and discuss potential outcomes with the family.

Conclusions

Although patients with WFNS grade V and brain herniation more often undergo ultra-early surgery, postoperative complication and outcomes in selected patients were similar between the ultra-early and delayed surgery groups. Patients of younger age, WFNS grade IV, absence of intraventricular haemorrhage, absence of brain herniation, and MCA aneurysms are more likely to have a good outcome. Ultra-early surgery could improve outcomes in carefully selected patients with poor-grade aSAH.

Footnotes

Contributors: BZ, YZ, XT, YC, JW, MZ and SW contributed to the study concept and design. BZ and JW contributed to the data collection and analysis. BZ, MZ and SW were involved in interpretation of the data. BZ was involved in drafting of the manuscript. BZ, YZ, XT, YC, JW, MZ and SW contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant numbers 2013BAI09B03, 2011BAI08B06), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81471210), Chinese Ministry of Health (grant number WKJ2010-2-016) and Wenzhou Bureau of Science and Technology (grant number Y20090005).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Chinese Ethics Committee of Registering Clinical Trials; Institutional Review Board of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kassell NF, Torner JC, Jane JA et al. . The International Cooperative Study on the timing of aneurysm surgery. Part 2: surgical results. J Neurosurg 1990;73:37–47. 10.3171/jns.1990.73.1.0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roos YB, Beenen LF, Groen RJ et al. . Timing of surgery in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: rebleeding is still the major cause of poor outcome in neurosurgical units that aim at early surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;63:490–3. 10.1136/jnnp.63.4.490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujii Y, Takeuchi S, Sasaki O et al. . Ultra-early rebleeding in spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1996;84:35–42. 10.3171/jns.1996.84.1.0035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fugate JE, Mallory GW, Wijdicks EF. Ultra-early aneurysmal rebleeding and brainstem destruction. Neurocrit Care 2012;17:439–40. 10.1007/s12028-011-9648-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Berg R, Foumani M, Schroder RD et al. . Predictors of outcome in World Federation of Neurologic Surgeons grade V aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. Crit Care Med 2011;39:2722–7. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182282a70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laidlaw JD, Siu KH. Ultra-early surgery for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: outcomes for a consecutive series of 391 patients not selected by grade or age. J Neurosurg 2002;97:250–8; discussion 47–9 10.3171/jns.2002.97.2.0250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailes JE, Spetzler RF, Hadley MN et al. . Management morbidity and mortality of poor-grade aneurysm patients. J Neurosurg 1990;72:559–66. 10.3171/jns.1990.72.4.0559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowak G, Schwachenwald R, Arnold H. Early management in poor grade aneurysm patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994;126:33–7. 10.1007/BF01476491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oda S, Shimoda M, Sato O. Early aneurysm surgery and dehydration therapy in patients with severe subarachnoid haemorrhage without ICH. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1996;138:1050–6. 10.1007/BF01412307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Versari PP, Talamonti G, D'Aliberti G et al. . Surgical treatment of poor-grade aneurysm patients. J Neurosurg Sci 1998;42(1 Suppl 1):43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang VL, Claus EB, Awad IA. Toward more rational prediction of outcome in patients with high-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2000;46:28–35; discussion 35–6 10.1097/00006123-200001000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang AP, Arora S, Wintermark M et al. . Perfusion computed tomographic imaging and surgical selection with patients after poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2010;67:964–74; discussion 75 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181ee359c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandstrom N, Yan B, Dowling R et al. . Comparison of microsurgery and endovascular treatment on clinical outcome following poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci 2013;20:1213–18. 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Roux PD, Elliot JP, Newell DW et al. . The incidence of surgical complications is similar in good and poor grade patients undergoing repair of ruptured anterior circulation aneurysms: a retrospective review of 355 patients. Neurosurgery 1996;38:887–93; discussion 93–5 10.1097/00006123-199605000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ungersbock K, Bocher-Schwarz H, Ulrich P et al. . Aneurysm surgery of patients in poor grade condition. Indications and experience. Neurol Res 1994;16:31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchinson PJ, Power DM, Tripathi P et al. . Outcome from poor grade aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage—which poor grade subarachnoid haemorrhage patients benefit from aneurysm clipping? Br J Neurosurg 2000;14:105–9. 10.1080/02688690050004516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips TJ, Dowling RJ, Yan B et al. . Does treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms within 24 hours improve clinical outcome? Stroke 2011;42:1936–45. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.602888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park J, Woo H, Kang DH et al. . Formal protocol for emergency treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms to reduce in-hospital rebleeding and improve clinical outcomes. J Neurosurg 2015;122:383–91. 10.3171/2014.9.JNS131784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong GK, Boet R, Ng SC et al. . Ultra-early (within 24 hours) aneurysm treatment after subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg 2012;77:311–15. 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connolly ES Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR et al. . Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2012;43:1711–37. 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steiner T, Juvela S, Unterberg A et al. . European Stroke Organization guidelines for the management of intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis 2013;35:93–112. 10.1159/000346087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wostrack M, Sandow N, Vajkoczy P et al. . Subarachnoid haemorrhage WFNS grade V: is maximal treatment worthwhile? Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013;155:579–86. 10.1007/s00701-013-1634-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson DA, Nakaji P, Albuquerque FC et al. . Time course of recovery following poor-grade SAH: the incidence of delayed improvement and implications for SAH outcome study design. J Neurosurg 2013;119:606–12. 10.3171/2013.4.JNS121287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor CJ, Robertson F, Brealey D et al. . Outcome in poor grade subarachnoid hemorrhage patients treated with acute endovascular coiling of aneurysms and aggressive intensive care. Neurocrit Care 2011;14:341–7. 10.1007/s12028-010-9377-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diaz RJ, Wong JH. Clinical outcomes after endovascular coiling in high-grade aneurysmal hemorrhage. Can J Neurol Sci 2011;38:30–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira AR, Sanchez-Pena P, Biondi A et al. . Predictors of 1-year outcome after coiling for poor-grade subarachnoid aneurysmal hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2007;7:18–26. 10.1007/s12028-007-0053-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bracard S, Lebedinsky A, Anxionnat R et al. . Endovascular treatment of Hunt and Hess grade IV and V aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:953–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki S, Jahan R, Duckwiler GR et al. . Contribution of endovascular therapy to the management of poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: clinical and angiographic outcomes. J Neurosurg 2006;105:664–70. 10.3171/jns.2006.105.5.664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitra D, Gregson B, Jayakrishnan V et al. . Treatment of poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage trial. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;36:116–20. 10.3174/ajnr.A4061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao B, Tan X, Yang H et al. . A Multicenter prospective study of poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (AMPAS): observational registry study. BMC Neurol 2014;14:86 10.1186/1471-2377-14-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otani N, Takasato Y, Masaoka H et al. . Surgical outcome following decompressive craniectomy for poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in patients with associated massive intracerebral or Sylvian hematomas. Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;26:612–7. 10.1159/000165115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heiskanen O, Poranen A, Kuurne T et al. . Acute surgery for intracerebral haematomas caused by rupture of an intracranial arterial aneurysm. A prospective randomized study. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1988;90:81–3. 10.1007/BF01560559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddiq F, Chaudhry SA, Tummala RP et al. . Factors and outcomes associated with early and delayed aneurysm treatment in subarachnoid hemorrhage patients in the United States. Neurosurgery 2012;71:670–7; discussion 77–8 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318261749b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laidlaw JD, Siu KH. Poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: outcome after treatment with urgent surgery. Neurosurgery 2003;53:1275–80; discussion 80–2 10.1227/01.NEU.0000093199.74960.FF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Roux PD, Elliott JP, Newell DW et al. . Predicting outcome in poor-grade patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a retrospective review of 159 aggressively managed cases. J Neurosurg 1996;85:39–49. 10.3171/jns.1996.85.1.0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirao S, Yoneda H, Kunitsugu I et al. . Preoperative prediction of outcome in 283 poor-grade patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a project of the Chugoku-Shikoku Division of the Japan Neurosurgical Society. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;30:105–13. 10.1159/000314713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mocco J, Ransom ER, Komotar RJ et al. . Preoperative prediction of long-term outcome in poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2006;59:529–38; discussion 29–38 10.1227/01.NEU.0000228680.22550.A2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iosif C, Di Maria F, Sourour N et al. . Is a high initial World Federation of Neurosurgery (WFNS) grade really associated with a poor clinical outcome in elderly patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms treated with coiling? J Neurointerv Surg 2014;6:286–90. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sasaki T, Sato M, Oinuma M et al. . Management of poor-grade patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in the acute stage: importance of close monitoring for neurological grade changes. Surg Neurol 2004;62:531–5; discussion 35–7 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shirao S, Yoneda H, Kunitsugu I et al. . Age limit for surgical treatment of poor-grade patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a project of the Chugoku-Shikoku division of the Japan neurosurgical society. Surg Neurol Int 2012;3:143 10.4103/2152-7806.103886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimoda M, Oda S, Shibata M et al. . Results of early surgical evacuation of packed intraventricular hemorrhage from aneurysm rupture in patients with poor-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1999;91:408–14. 10.3171/jns.1999.91.3.0408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]