Abstract

Objective

To identify factors associated with anaemia in lactating mothers in Ethiopia.

Design

A cross-sectional secondary analysis of data pooled from two rounds of the 2005 and 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) was used. A multivariate logistic regression model was applied to determine the factors associated with anaemia.

Population

A total of 7332 lactating mothers (2285 from EDHS 2005 and 5047 from EDHS 2011) were included from 11 administrative states of Ethiopia.

Main outcome measures

Lactating mothers considered anaemic if haemoglobin level <12 g/dL.

Results

The overall prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers was 22.1% (95% CI 21.13% to 23.03%). The highest prevalence was 48.7% (95% CI 40.80% to 56.62%) found in the Somali region, followed by 43.8% (95% CI 31.83% to 56.87%) in the Afar region. The multivariate statistical model showed that having a husband who had attended primary education (adjusted OR (AOR) 0.79; 95% CI 0.68 to 0.91), working during the 12 months preceding the survey (AOR 0.71; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.80), having a normal maternal body mass index (18.5–24.99 kg/m2) (AOR 0.78; 95% CI 0.68 to 0.89), being in the middle wealth quintile (AOR 0.83; 95% CI 0.71 to 0.98) or rich wealth quintile (AOR 0.83; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.98), having ever used family planning (AOR 0.68; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.80), having attended antenatal care (ANC) for the indexed pregnancy four times or more (AOR 0.73; 95% CI 0.59 to 0.91), having experienced time variation between the two surveys (AOR 0.73; 95% CI 0.64 to 0.85), and breastfeeding for 2 years (AOR 0.76; 95% CI 0.66 to 0.87) were factors associated with lower odds of having anaemia in lactating mothers.

Conclusions

Anaemia is highly prevalent among lactating mothers, particularly in the pastoralist communities of Somali and Afar. Promoting partner education, improving maternal nutritional status, and creating behavioural change to use family planning and ANC services at health facilities are recommended interventions to reduce the prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers in Ethiopia.

Keywords: NUTRITION & DIETETICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study aimed to identify factors associated with laboratory-confirmed anaemia among lactating mothers at the national level. The study findings can be used to inform policy and programme actions.

Some regions from which data were collected had a small sample size, and so findings should be interpreted with caution.

This study also shares the limitation of a cross-sectional design, which makes it difficult to demonstrate cause-and-effect relationships.

Introduction

Anaemia is a serious nutrition problem affecting millions in developing countries and remains a major challenge for human health and social and economic development.1 Lactating mothers are vulnerable to anaemia. During the period of lactation, mothers are susceptible to anaemia because of maternal iron depletion and blood loss during childbirth.2 Studies have shown that, although breast milk is not a good source of iron, the concentration of iron in breast milk is independent of maternal iron status. This indicates that the quality of breast milk is maintained at the expense of maternal stores.2 3

Postpartum anaemia is highest in mothers who are anaemic during pregnancy.4 Furthermore, lactating mothers are highly susceptible to iron depletion if the energy and nutrient intake in their diets is inadequate. Lactating mothers begin the postnatal period after having iron depleted through the continuum from pregnancy to childbearing.5 A study from South Africa showed that iron status was associated with depression, stress and cognitive functioning in poor African mothers during the postpartum period.6 In a meta-analysis of observational and intervention trials, Ross and Thomas7 found that ∼20% of maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia was attributable to anaemia that was primarily the result of iron deficiency.

Ethiopia is one of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa affected by anaemia, and it contributes to high rates of maternal, infant and child mortality globally.8 9 In Ethiopia, the maternal mortality rate is 676 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births,10 which is one of the highest in the world. The country has very high infant and under-5 mortality rates, which account for 59 and 88 deaths per 1000 live births, respectively.10

Anaemia testing was included in the two rounds of the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS). The prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers was 29.9% in 2005 and 18.5% in 2011.10 11 It was 30.6% in 2005 and 22% in 2011 among pregnant women, and 23.9% in 2005 and 15% in 2011 among women who were neither pregnant nor lactating. This shows that the prevalence of anaemia was higher among pregnant and lactating mothers in Ethiopia. However, little information is available on the socio-demographic factors associated with anaemia in lactating mothers. This study aimed to identify factors associated with anaemia in lactating mothers in Ethiopia using the pooled data of EDHS 2005 and 2011.

Methods

Data type and study design

This analysis used secondary data from the 2005 and 2011 EDHS to identify factors associated with anaemia in lactating mothers. Both the 2005 and 2011 EDHS samples were selected using a stratified, two-stage cluster sampling design. All women aged 15–49 who were usually resident or who had slept in the selected households on the night before the survey were eligible. The EDHS data include a women's questionnaire that measures socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers, information on reproductive health and service use behaviours, as well as results of HIV and anaemia tests. The tool was pretested and translated into three local languages: Amharic, Oromefa and Tigregna. The EDHS was designed to provide population and health indicators at national and regional levels. The survey is conducted every 5 years. The detailed methodology can be found elsewhere.10 11

Data extraction

Both EDHS 2005 and 2011 data were downloaded, with permission, from the Measure DHS website in SPSS format. After a review of the detailed data coding, further data recoding was completed. A total of 7332 lactating mothers (2285 from EDHS 2005 and 5047 from EDHS 2011) were included in the analysis. Based on published literature, information on a wide range of socio-demographic and economic variables, health-service-related factors and anaemia level indicators were extracted. The chosen variables were region, residence, wealth index, occupation, body mass index (BMI), duration of breastfeeding, respondent's education, husband's education, family planning use, iron tablet supplementation during pregnancy, time variation between the two surveys, marital status, age, parity and antenatal care (ANC) attendance.

Measurement of variables

In both rounds of the EDHS, haemoglobin analysis was carried out on site using a battery-operated portable HemoCue analyser for all anaemia samples. The raw measured concentrations of haemoglobin were obtained using the HemoCue instrument and adjusted for altitude and smoking status.10 Lactating mothers were considered to be anaemic if their haemoglobin level was <12 g/dL. Haemoglobin level was measured in g/dL, operationalised as a categorical variable by predefined cut-off points for mild, moderate and severe anaemia recommended by the WHO for women above the age of 15 years. For this analysis, we recategorised anaemia level as anaemic and non-anaemic from prior classifications in levels (no, mild, moderate, severe) because of very small numbers of cases in the categories of severe and mild anaemia in all datasets of pooled and individual surveys.

ANC attendance refers to obtaining services during pregnancy according to the WHO recommendation of at least four ANC visits for low-risk pregnant women. The frequency of ANC visits was measured by asking the respondent to recall how many times she had attended for the indexed child. Occupational status was defined as non-working and working, which comprises professional/technical/managerial, clerical, sales and services, skilled manual, unskilled manual and agriculture classifications. BMI (kg/m2) was categorised using the standard WHO classification into underweight <18.5 kg/m2, normal 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight 25.0 kg/m2 and above. Parity, defined as the number of children ever born, was categorised as 1–4, 5–9 and 10+. The wealth index, constructed from household assets and characteristics available in both surveys to categorise individuals into wealth quintiles (poorest, poorer, middle, rich and richest), was used. For the present analysis, the wealth index was collapsed into three groups (poor, middle and rich) to give meaningful and practical sub-population categories for designing programme interventions in the general community.

Statistical analysis

For this study, the 2005 and 2011 EDHS data were pooled to achieve high power for detecting the associated factors. Sample weights were applied to compensate for the unequal probability of selection between the strata, which has also been geographically defined for non-responses. A detailed explanation of the weighting procedure can be found in the EDHS methodology report.10 We used ‘svy’ in Stata V.11 to weight the survey data and perform the analyses.

Descriptive statistics were used to show the prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers varying by background characteristics. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression statistical analysis was carried out to determine the factors associated with anaemia in lactating mothers. Variables found statistically significant at p<0.25 during bivariate analysis were analysed in the multivariate logistic regression model.12 This p value cut-off point prevented removal of variables that would potentially have an effect during multivariate analysis. Both crude and adjusted ORs were reported with 95% CI. Variables with p<0.05 were considered significant in the multivariate logistic regression model.

Ethics statements

The data were downloaded and used after communicating the purpose of the analysis and receiving permission from the Measure DHS Organisation. The original EDHS data were collected in accordance with international and national ethical guidelines.

Results

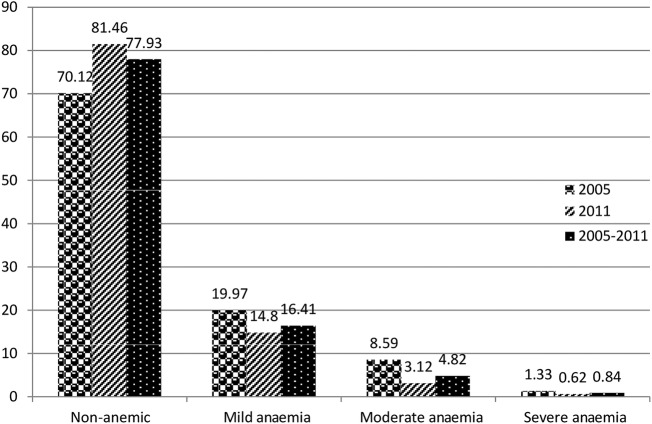

Most respondents (86%) were from rural areas. Nearly 60% of lactating mothers were Christians and 38% were Muslims. The mean age of the respondents was 28.4 (SD 6.8) years. The overall prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers during 2005–2011 was 22.1% (95% CI 21.13% to 23.03%). The prevalence of anaemia for the years 2005 and 2011 was 29.9% (95% CI 28.04% to 31.79%) and 18.5% (95% CI 17.45% to 19.60%), respectively. The prevalence was 13.8% (95% CI 11.44% to 16.41%) in urban areas and 23% (95% CI 21.99% to 24.03%) in rural areas. In the period 2005–2011, the highest prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers was 48.7% (95% CI 40.80% to 56.62%) found in the Somali region, while the lowest prevalence was 9.0% (95% CI 4.07% to 15.47%) reported in Addis Ababa. In the period 2005–2011, the prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers was consistently higher in those in the poor wealth index group, not currently working, with BMI ≥25 kg/m2, with 1 year duration of breastfeeding, never educated, never used ANC, never used family planning services, no iron tablet supplement during pregnancy, and with higher parity. A significant reduction in the prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers was observed in all background variables from 2005 to 2011 (table 1). Figure 1 shows the classification of anaemia in terms of its detailed variables.

Table 1.

Prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers by background characteristics in Ethiopia using pooled data from the EDHS 2005 and 2011

| 2005 |

2011 |

2005–2011 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background characteristic | Total lactating women† | Prevalence of anaemia (95% CI) | Total lactating women† | Prevalence of anaemia (95% CI) | Total lactating women† | Prevalence of anaemia (95% CI) |

| Region | ||||||

| Tigray | 142 | 35.4 (27.69 to 43.33) | 281 | 13.4 (9.89 to 17.90) | 422 | 20.8 (17.18 to 24.93) |

| Afar | 22 | 46.2 (25.88 to 66.16) | 38 | 42.4 (27.27 to 58.10) | 59 | 43.8 (31.83 to 56.87) |

| Amhara | 591 | 32.2 (28.47 to 36.00) | 1352 | 18.9 (16.91 to 21.09) | 1943 | 22.9 (21.12 to 24.86) |

| Oromia | 826 | 28.5 (25.45 to 31.60) | 2041 | 20.1 (18.39 to 21.87) | 2867 | 22.5 (21.00 to 24.05) |

| Somali | 60 | 49.2 (37.50 to 62.50) | 92 | 48.3 (37.76 to 58.02) | 152 | 48.7 (40.80 to 56.62) |

| Benshangul-gumz | 24 | 26.8 (10.81 to 44.92) | 59 | 20.5 (11.51 to 32.02) | 83 | 22.9 (14.81 to 32.83) |

| SNNPR | 578 | 26.2 (22.66 to 29.82) | 1059 | 13.5 (11.54 to 15.66) | 1637 | 18.0 (16.16 to 19.88) |

| Gambella | 6 | 46.5 (14.66 to 85.34) | 18 | 23.2 (7.49 to 45.31) | 25 | 28.0 (13.15 to 47.7) |

| Harari | 3 | 27.1 (1.67 to 86.80) | 10 | 23.4 (3.50 to 51.95) | 15 | 20.0 (5.35 to 45.35) |

| Addis Ababa | 27 | 14.4 (4.89 to 31.97) | 83 | 7.3 (2.98 to 14.43) | 111 | 9.0 (4.07 to 15.47) |

| Dire Dawa | 5 | 33.0 (7.35 to 81.76) | 13 | 35.8 (15.68 to 65.91) | 18 | 33.3 (14.77 to 56.9) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 145 | 19.4 (13.49 to 26.34) | 595 | 12.4 (9.96 to 15.27) | 740 | 13.8 (11.44 to 16.41) |

| Rural | 2140 | 30.6 (28.68 to 32.59) | 4452 | 19.4 (18.27 to 20.59) | 6592 | 23.0 (21.99 to 24.03) |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poor | 986 | 32.2 (29.29 to 35.12) | 2306 | 21.4 (19.74 to 23.09) | 3293 | 24.6 (23.15 to 26.09) |

| Middle | 517 | 29.9 (26.15 to 34.04) | 1102 | 17.0 (14.84 to 19.27) | 1619 | 21.1 (19.19 to 23.16) |

| Rich | 782 | 27.0 (23.96 to 30.18) | 1639 | 15.6 (13.86 to 17.37) | 2420 | 19.3 (17.76 to 20.91) |

| Current occupational status | ||||||

| Not working | 1568 | 31.8 (29.55 to 34.16) | 2325 | 21.0 (19.37 to 22.68) | 3893 | 25.4 (24.06 to 26.29) |

| Working* | 712 | 25.5 (22.46 to 28.86) | 2722 | 16.4 (15.03 to 17.81) | 3434 | 18.3 (17.02 to 19.61) |

| BMI | ||||||

| <18.5 | 481 | 33.9 (29.76 to 38.21) | 1138 | 19.3 (17.12 to 21.70) | 1619 | 23.6 (21.57 to 25.71) |

| 18.5–24.99 | 1729 | 28.3 (26.20 to 30.44) | 3723 | 18.1 (16.89 to 19.37) | 5453 | 21.3 (20.22 to 22.39) |

| 25+ | 65 | 42.1 (30.05 to 53.76) | 175 | 20.4 (15.07 to 27.04) | 240 | 26.3 (20.98 to 32.09) |

| Duration of breastfeeding (years) | ||||||

| 1 | 1072 | 30.7 (27.98 to 33.50) | 2461 | 20.6 (19.04 to 22.23) | 3533 | 23.7 (22.31 to 25.11) |

| 2 | 728 | 26.6 (23.53 to 29.95) | 1490 | 15.4 (13.61 to 17.27) | 2218 | 19.1 (17.52 to 20.79) |

| 3+ | 478 | 32.5 (28.34 to 36 to 72) | 1096 | 18.2 (15.96 to 20.52) | 1575 | 22.6 (20.59 to 24.72) |

| Mother's education | ||||||

| None | 1804 | 31.8 (29.70 to 34.00) | 3486 | 19.2 (17.91 to 20.52) | 5291 | 23.5 (22.36 to 24.65) |

| Primary | 394 | 24.3 (20.32 to 28.79) | 1377 | 18.3 (16.32 to 20.41) | 1770 | 19.6 (17.80 to 21.50) |

| Secondary | 79 | 17.3 (10.46 to 27.31) | 126 | 8.3 (4.10 to 13.69) | 205 | 11.8 (7.83 to 16.67) |

| Higher | 8 | 1.1 (0.63 to 48.03) | 58 | 9.7 (4.30 to 20.28) | 66 | 8.7 (3.77 to 17.95) |

| Husband's education | ||||||

| None | 1333 | 33.9 (31.40 to 36.48) | 2531 | 20.3 (18.77 to 21.91) | 3864 | 25.0 (23.65 to 26.38) |

| Primary | 701 | 26.2 (23.09 to 29.60) | 2048 | 17.2 (15.60 to 18.87) | 2749 | 19.5 (18.05 to 21.01) |

| Secondary | 199 | 20.7 (15.41 to 26.64) | 238 | 14.3 (10.26 to 19.17) | 437 | 17.2 (13.84 to 20.92) |

| Higher | 23 | 14.8 (3.43 to 31.53) | 147 | 13.7 (8.75 to 19.88) | 170 | 13.8 (8.99 to 19.30) |

| Family planning | ||||||

| Never used | 1775 | 32.1 (29.97 to 34.31) | 2889 | 21.2 (19.72 to 22.70) | 4663 | 25.4 (24.16 to 26.66) |

| Ever used | 15 | 16.4 (2.30 to 37.52) | 2158 | 14.9 (13.46 to 16.47) | 2173 | 14.9 (13.46.16.45) |

| ANC use | ||||||

| Never | 1636 | 32.0 (29.80 to 34.32) | 2977 | 20.4 (18.97 to 21.87) | 4613 | 24.5 (23.27 to 25.75) |

| 1–3 times | 386 | 27.7 (23.43 to 32.35) | 1208 | 18.4 (16.27 to 20.64) | 1594 | 20.6 (18.65 to 22.62) |

| 4+ times | 260 | 18.9 (14.44 to 23.95) | 845 | 12.6 (10.44 to 14.91) | 1105 | 14.1 (12.16 to 16.27) |

| Iron supplementation during pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 2046 | 30.1 (28.15 to 32.12) | 4196 | 18.8 (17.64 to 20.01) | 6242 | 22.5 (21.47 to 23.54) |

| Yes | 236 | 27.1 (21.74 to 33.06) | 840 | 16.9 (14.48 to 19.55) | 1076 | 19.2 (16.97 to 21.68) |

| Parity | ||||||

| 1–4 | 1293 | 28.9 (26.50 to 31.44) | 3111 | 18.1 (16.77 to 19.48) | 4404 | 21.3 (20.11 to 22.53) |

| 5–9 | 903 | 30.5 (27.52 to 33.52) | 1739 | 19.6 (17.79 to 21.53) | 2642 | 23.3 (21.73 to 24.96) |

| 10+ | 89 | 37.1 (27.53 to 47.46) | 197 | 17.0 (12.02 to 12.46) | 287 | 23.2 (18.72 to 28.50) |

| Total | 2285 | 29.9 (28.04 to 31.79) | 5047 | 18.5 (17.45 to 19.60) | 7332 | 22.1 (21.13 to 23.03) |

*Professional/technical/managerial, clerical, sales and services, skilled manual, unskilled manual and agriculture. †The numbers are weighted. ANC, antenatal care; BMI, body mass index; EDHS, Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers in Ethiopia, 2005–2011.

In the bivariate step of our analysis, age and marital status were not statistically significant in the data from both individual surveys and pooled data with the cut-off point p<0.25. The variable associated with anaemia for the 2005 data was BMI, whereas for the 2011 data associated variables were working status, wealth index, ever use of family planning, ANC attendance four times or more for indexed pregnancy, husband's education, maternal BMI and duration of breastfeeding.

In the final multivariate model using pooled data, the independent predictors of anaemia for Ethiopian lactating mothers were currently working, wealth index, ever use of family planning, ANC attendance four times or more for indexed pregnancy, husband's education, maternal BMI, time variation in the two surveys, and duration of breastfeeding.

Paternal educational status was found to be a predictor of anaemia in lactating mothers. Lactating mothers with husbands who had attended primary education were 21% less likely to have anaemia than those who had husbands with no education (adjusted OR (AOR) 0.79; 95% CI 0.68 to 0.91). The odds of working lactating mothers being anaemic was 29% less than their counterparts (AOR 0.71; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.80). Lactating mothers with a normal maternal BMI (18.5–24.99 kg/m2) were 22% less likely to be anaemic than lactating mothers with low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) (AOR 0.78; 95% CI 0.68 to 0.89). Similarly, lactating women categorised in the middle (AOR 0.83; 95% CI 0.71 to 0.98) and rich (AOR 0.83; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.98) wealth quintiles were each 17% less likely to have anaemia than lactating women in poorer wealth quintiles.

Of the reproductive characteristics, family planning use and ANC were significant factors associated with anaemia in lactating mothers. Lactating mothers who had ever used family planning were 32% less likely to have anaemia than lactating mothers who had never used family planning (AOR 0.68; 95% CI 0.57 to 0.80). Lactating mothers who reported ANC attendance four times or more for indexed pregnancy were 27% less likely to have anaemia than mothers who never attended ANC (AOR 0.73; 95% CI 0.59 to 0.91). Lactating mothers who fed breast milk for 2 years were 24% less likely to have anaemia than lactating women who fed breast milk for 1 year (AOR 0.76; 95% CI 0.66 to 0.87) (table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with anaemia in lactating mothers in Ethiopia using pooled data from the EDHS 2005 and 2011

| 2005 |

2011 |

2005–2011 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Not working | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Working | 0.82 (0.66 to 1.00) | 0.83 (0.64 to 1.06) | 0.62 (0.54 to 0.71) | 0.68 (0.58 to 0.78) | 0.64 (0.57 to 0.72) | 0.71 (0.63 to 0.80) |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poor | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Middle | 0.71 (0.54 to 0.92) | 0.82 (0.61 to 1.10) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.89) | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.04) | 0.74 (0.64 to 0.87) | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.98) |

| Rich | 0.66 (0.53 to 0.82) | 0.91 (0.68 to 1.22) | 0.62 (0.52 to 0.72) | 0.80 (0.65 to 0.97) | 0.65 (0.57 to 0.73) | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.98) |

| Family planning use | ||||||

| Never used | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ever used | 0.37 (0.11 to 1.28) | 0.51 (0.14 to 1.91) | 0.54 (0.46 to 0.63) | 0.69 (0.58 to 0.82) | 0.48 (0.41 to 0.55) | 0.68 (0.57 to 0.80) |

| ANC attended | ||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1–3 | 0.78 (0.59 to 1.03) | 0.94 (0.66 to 1.33) | 0.78 (0.59 to 1.00) | 1.00 (0.83 to 1.2) | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.94) | 0.99 (0.84 to 1.16) |

| 4+ | 0.55 (0.41 to 0.74) | 0.82 (0.53 to 1.28) | 0.55 (0.41 to 0.74) | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.92) | 0.52 (0.44 to 0.61) | 0.73 (0.59 to 0.91) |

| Husband's education | ||||||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.96) | 0.77 (0.58 to 1.01) | 0.69 (0.59 to 0.80) | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.94) | 0.69 (0.61 to 0.78) | 0.79 (0.68 to 0.91) |

| Secondary | 0.55 (0.39 to 0.77) | 0.83 (0.50 to 1.38) | 0.64 (0.48 to 0.87) | 0.81 (0.58 to 1.14) | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.77) | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.09) |

| Higher | 0.58 (0.26 to 1.30) | 0.50 (0.73 to 3.40) | 0.72 (0.49 to 1.0) | 0.96 (0.61 to 1.52) | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.90) | 0.94 (0.61 to 1.45) |

| Maternal BMI | ||||||

| <18.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 18.5–24.99 | 0.74 (0.59 to 0.92) | 0.76 (0.59 to 0.99) | 0.74 (0.64 to 0.86) | 0.79 (0.68 to 0.93) | 0.76 (0.67 to 0.86) | 0.78 (0.68 to 0.89) |

| 25+ | 1.1 (0.62 to 1.90) | 1.66 (0.79 to 3.48) | 0.82 (0.58 to 1.2) | 1.12 (0.77 to 1.62) | 0.85 (0.64 to 1.12) | 1.21 (0.87 to 1.68) |

| Duration of breastfeeding (years) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 0.79 (0.64 to 0.99) | 0.79 (0.62 to 1.03) | 0.71 (0.60 to 0.83) | 0.75 (0.63 to 0.88) | 0.75 (0.66 to 0.85) | 0.76 (0.66 to 0.87) |

| 3+ | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.27) | 1.10 (0.82 to 1.49) | 0.71 (0.59 to 0.86) | 0.82 (0.67 to 0.99) | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.94) | 0.89 (0.76 to 1.05) |

| Time laps | ||||||

| 2005 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2011 | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.73) | 0.73 (0.64 to 0.85) | ||||

1.00 is the reference category. ANC, antenatal care; AOR, adjusted OR; BMI, body mass index; COR, crude OR; EDHS, Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey.

Discussion

Over one-fifth of lactating mothers were anaemic in Ethiopia, which is lower than in other developing countries. For example, 66.0% of lactating mothers have been reported as having anaemia in India,13 and 43.8% of lactating mothers in Kenya had a haemoglobin level <12 g/dL.14 Another study from Myanmar reported an anaemia prevalence rate of 60.3% in lactating women, with 20.3% of lactating mothers having severe anaemia.15 Although the prevalence of anaemia among lactating mothers in Ethiopia was relatively low compared with these studies, it remains a public health problem according to WHO classification.16 The lower prevalence of anaemia in Ethiopia among lactating mothers may be due to the cultural norms of providing nutritional care to lactating mothers during the postpartum period. Lactating mothers are encouraged to rest for 3–6 months and to eat a variety of foods including animal sources, even during religious fasting periods. Iron supplementation in pregnant mothers remains low in Ethiopia10 despite its known contribution to reducing the risk of postpartum haemorrhage17 Postpartum haemorrhage was also found to be one of the risk factors for anaemia during the period of lactation.17

This study shows that anaemia is a widespread problem in the pastoralist communities of Somali and Afar. The prevalence of anaemia in lactating mothers was found to be higher in the pastoralist regions and showed slow decline in these regions from 2005 to 2011. This may be because pastoralist communities are heavily dependent on animal milk, which has low iron bioavailability, as a source of daily food.18 19 The other reason may be low utilisation of family planning and ANC services in pastoralist areas.10

One of the factors found to be associated with anaemia was paternal education. Having a husband with a higher level of education was found to be associated with lower odds of a lactating mother having anaemia. This may be because educated husbands might support their wives in the use of modern health services such as family planning, ANC and postnatal care, which in turn reduce the odds of having anaemia, as well advising them to eat a diverse diet.

However, maternal educational status was not statistically associated with anaemia, which is in contradiction to many other studies from Ethiopia and abroad.15 20–22 This might be an important motivator to involve husbands in anaemia-prevention efforts.

Lactating mothers who had been working in the 12 months preceding the survey had lower odds of having anaemia than their counterparts. This may be because working mothers were earning money as compared with non-working mothers and the extra income enabled them to access and purchase more food items, including animal sources (meat, poultry, fish), and increase dietary diversity. Studies have shown that income growth improves diet diversity, which in turn improves intake of micronutrients, including iron.23 24 Similarly, lactating mothers in the lower wealth quintiles had greater odds of having anaemia than those in the higher wealth quintiles. In many other studies of anaemia in reproductive-age women, the wealth index was found to be a statistically significant factor.15 20 Further studies have also shown that women of low socio-demographic status are at risk of iron deficiency anaemia in late pregnancy and in the postpartum period.25 26 Therefore, women's empowerment through economic interventions and working status may provide a positive contribution to preventing anaemia.

This study also supports the importance of family planning for reducing the risk of anaemia. Lactating mothers who have ever used family planning (modern or traditional) had lower odds of having anaemia than those who had never used family planning. This finding is consistent with studies from Ethiopia and Timor-Leste which showed that use of family planning was associated with lower odds of having anaemia.20 27

Maternal nutritional status (as measured by BMI) was found to be significantly associated with anaemia. As compared with undernourished lactating mothers (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), being in the normal BMI category (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) was associated with lower odds of having anaemia. This finding is consistent with studies from Ethiopia and Thailand.20 28 When a mother is at risk of deficiency of macronutrients, she is most likely also at risk of other micronutrient deficiencies such as iron.29

ANC attendance was found to be associated with lower odds of lactating mothers having anaemia. This is most likely because mothers are advised during ANC attendance to take iron supplements according to the Ethiopian micronutrient guidelines and instructed to consume different sources of iron-rich food items.30 Therefore, improving iron status during pregnancy also helps to prevent anaemia during the lactation period.

Lactating mothers who fed breast milk for 2 years had lower odds of having anaemia than those who fed breast milk for 1 year. This may be due to the effect of breastfeeding on maternal depletion. Those mothers who breastfeed younger children might have a higher burden of breastfeeding than mothers who fed the older children. A study by Gebremedhin et al20 also found that breastfeeding increases the risk of anaemia significantly.

One of the strengths of this study is the use of laboratory-confirmed anaemia data at the national level. Therefore, the study findings can be used to inform policy and programme actions. However, there is the caveat that some regions had a small sample size, which questions the accuracy of prevalence estimates per region, so findings should be interpreted with caution. The study did not determine the presence of soil-transmitted helminth infection, which is associated with anaemia. This study also has the limitation of a cross-sectional study design, which makes it difficult to demonstrate cause-and-effect relationships.

Conclusion

Anaemia is a public health problem in lactating mothers in Ethiopia. There are regional disparities regarding the prevalence of anaemia, with the highest found in the pastoralist regions of Somali and Afar. Promoting partner education, improving maternal nutritional status, and creating behavioural change to use family planning and attend ANC services at health facilities are recommended interventions to reduce the prevalence of anaemia among lactating women in Ethiopia.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge measure DHS for granting free access to the data. We are also grateful to Lianna Tabar, country representative of KHI-E, for her professional language editing and reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: YL and DH conceptualised the research idea. YL analysed and interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. SB assisted in data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. DH drafted the manuscript, assisted in the data analysis and interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute (EHNRI) Review Board, the National Research Ethics Review Committee (NRERC) at the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Institutional Review Board of ICF International, and the CDC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.WHO. The world health report. Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitney E, Rolfes SR. Understanding Nutrition. In: Adams P, ed. 11th edn USA: Thomson Learning Academic Resource Center, 2008:533–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domell V, Lonnerdal B, Dewey K et al. . Iron zinc and copper concentrations in breast milk are independent of maternal status. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:111–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodnar L, Scanlon K, Freedman D et al. . High prevalence of postpartum anaemia among low income women in the United States. J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185:4348–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sserunjogi L, Scheut F, Whyte SR. Postnatal anaemia: neglected problems and missed opportunities in Uganda. Health Policy Plan 2003;18:225–31. 10.1093/heapol/czg027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beard JL, Hendricks MK, Perez EM et al. . Maternal iron deficiency anemia affects postpartum emotions and cognition. J Nutr 2005;135:267–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross J, Thomas E. Iron deficiency anemia and maternal mortality. PROFILES 3 working notes series no. 3. Washington, DC: Academy for Education Development, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brabin BJ, Hakimin M, Pelletier D. An analysis of anemia and pregnancy-related maternal mortality. J Nutr 2001;131:604S–15S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M et al. . A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood 2014;123:615–24. 10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Central Statistical Agency (CSA) Ethiopia. Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: CSA and ORC Macro, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Central Statistical Agency (CSA). Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: CSA and ORC Macro, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin PC, Tu JV. Automated variable selection methods for logistic regression produced unstable models for predicting acute myocardial infarction mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:1138–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh AB, Kandpal SD, Chandra R et al. . Anemia amongst pregnant and lactating women in district Dehradun. Indian J Prev Soc Med 2009;40:20–1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ettyanga GA, Oloob WDvMLA, Saris WHM. Serum retinol, iron status and body composition of lactating women in Nandi, Kenya. Ann Nutr Metab 2003;47:276–83. 10.1159/000072400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao A, Zhang Y, Li B et al. . Prevalence of anemia and its risk factors among lactating mothers in Myanmar. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90:963–7. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHO. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005: WHO global database on anaemia. Edited by B de Benoist, E McLean, I Egli, M Cogswell, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO. Recommendations for the Prevention of Postpartum Haemorrhage (summary of results from a WHO technical consultation, October 2006). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kibangou I, Bouhallab S, Henry G et al. . Milk proteins and iron absorption: contrasting effects of different caseinophosphopeptides. Pediatr Res 2005;58:731–4. 10.1203/01.PDR.0000180555.27710.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belachew T. Human nutrition lecture note series for health sciences students. Jimma University, 2005:229. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gebremedhin S, Enquselassie F. Correlates of anemia among women of reproductive age in Ethiopia: evidence from Ethiopian DHS 2005. Ethiop J Health Dev 2011;25:22–30. 10.4314/ejhd.v25i1.69842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haidar J. Prevalence of anaemia, deficiencies of iron and folic acid and their determinants in ethiopian women. J Health Popul Nutr 2010;28:359–68. 10.3329/jhpn.v28i4.6042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okwu GN. Studies on the predisposing factors of iron deficiency anaemia among lactating women in Owerri, Nigeria. Int Res J Biochem Bioinform 2011;1:304–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taruvinga A, Muchenje V, Mushunje A. Determinants of rural household dietary diversity: the case of Amatole and Nyandeni districts, South Africa. Int J Dev Sustainability 2013;2:2233–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doan D. Does income growth improve diet diversity in China? Selected paper prepared for presentation at the 58th AARES Annual Conference, Port Macquarie, New South Wales, 4–7 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodnar L, Cogswell M, Scanlon K. Low income postpartum women are at risk of iron deficiency. J Nutr 2002;132:2298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadeghian M, Fatourechi A, Lesanpezeshki M et al. . Prevalence of anemia and correlated factors in the reproductive age women in rural areas of Tabas. J Fam Reprod Health 2013;7:143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovermail AA, Hartman M, Chia KS et al. . Demographic and spatial predictors of anemia in women of reproductive age in Timor-Leste: implications for Health Program Prioritization. PLoS ONE 2013;9:e91252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liabsuetrakul T, for Southern Soil-transmitted Helminths and Maternal Health Working Group. Is international or Asian criteria-based body mass index associated with maternal anaemia, low birthweight, and preterm births among Thai population?—An observational study. J Health Popul Nutr 2011;29:218–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumfield M, Hure A, MacDonald-Wicks L et al. . The association between the macronutrient content of maternal diet and the adequacy of micronutrients during pregnancy in the Women and Their Children's Health (WATCH) study. Nutrients 2012;4:1958–76. 10.3390/nu4121958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Federal Ministry of Health-Ethiopia. National guideline for control and prevention of micronutrient deficiencies, 2004.