Abstract

Introduction

Acupuncture has been used worldwide for migraine attacks. This systematic review aims to assess if acupuncture is effective and safe in relieving headache, preventing relapse and reducing migraine-associated symptoms for the treatment of acute migraine attacks in adults.

Methods and analysis

We will search the following seven databases from inception to February 2015: MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and four Chinese databases (Chinese Biomedical Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database and Wanfang Database). Any randomised controlled trials in English or Chinese related to acupuncture for acute migraine attacks will be included. Conference abstracts and reference lists of included manuscripts will also be searched. The study inclusion, data extraction and quality assessment will be conducted independently by two reviewers. Meta-analysis will be performed using RevMan V.5.3.5 statistical software.

Dissemination

The findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publication and/or conference presentations.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO CRD42014013352.

Keywords: COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE, PAIN MANAGEMENT

Introduction

Description of the condition

Migraine is a prevalent neurovascular headache disorder, which is characterised by recurrent attacks of unilateral pulsating moderate-to-severe headaches. The headaches usually last 4–72 h and have concomitant symptoms such as light and sound sensitivity, nausea and vomiting. Migraine can be triggered by food, environment and mental factors, and may be aggravated by routine physical activity. Symptoms usually start at puberty and have two major subtypes: migraine with aura and migraine without aura. The former is characterised by visual, sensory or central nervous system symptoms before the onset of headache and associated migraine symptoms, while the latter does not have the premonitory symptomatology.1 The pathophysiology of migraine is still widely debated.2–4 The prevailing view is that the activation and sensitisation of trigeminovascular meningeal nociceptors start the headache phase of migraine. Then the second-order and third-order central trigeminovascular neurons are activated, which in turn activate different areas of the brain stem and forebrain, resulting in pain and other accompanying migrainous symptoms.4

Population-based surveys have shown that migraine occurs in at least one in every seven adults worldwide,5 and affects women threefold more than men.6 In the Global Burden of Disease Survey 2010, migraine was ranked as the third most prevalent disorder and seventh highest specific cause of disability worldwide.7 Migraine seriously impacts the patient's health and quality of life, and is often a source of great disability, with migraineurs’ normal activities limited up to 78% during migraine attacks.8 Patients with migraine may also be afflicted with fear in the period between episodes of headache attack.9 Meanwhile, the consequent economic burden of migraine is enormous.10 11 A research based on the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study showed that the average annual direct cost per person of episodic migraine was $1757 in the USA.12 A cross-sectional survey in eight European Union countries representing 55% of the adult population has estimated a mean annual cost of migraine per person of €1222 and a total annual cost of €111 billion for adults aged 18–65 years.13 An association between migraine and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases has also been shown by numerous studies.14 A systematic review of studies investigating migraine and cardiovascular disease (n=25) found that the risk of ischaemic stroke was doubled in people who had migraine with aura.15

Description of the intervention

Acupuncture plays an important role in traditional Chinese medicine with a history of thousands of years. It treats disease by inserting needles along specific pathways or meridians. Acupuncture is utilised worldwide to treat headache, including migraine.16–22 Of patients in the USA who accept acupuncture as a valid treatment, 9.9% said that they had been treated with acupuncture for migraine or other headaches.23 In 1998, acupuncture was suggested as an adjunct or an alternative treatment for headache by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).24 It was also suggested by the China Association for the Study Pain (CASP) as a complementary and alternative treatment for migraine.25 26

Potential therapeutic mechanisms of acupuncture in migraine

Some theories may explain the mechanism of acupuncture in headache relief. Studies suggested that acupuncture could inhibit pain transmission to the central nervous system by stimulating different types of afferent fibres (eg, Aβ, Aδ).27 Acupuncture was also found to be able to facilitate the release of some pain suppressors including endorphins, which are opiate chemical substances, within the central nervous system.28 29

Justification and significance of the review

For the treatment of migraine, the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) recommended treatment addressing acute attacks as well as prophylaxis.30 Typical treatments for acute migraine include analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and triptans.26 Triptans account for almost 80% of antimigraine analgesics.31 However, about one-third of patients with migraine using triptans did not get headache relief at 2 h after taking medication, and over half were willing to try other treatments.26 32 33 There are unmet needs in acute migraine treatment.34 35

Acupuncture has been used for both migraine attacks and prevention. A Cochrane systematic review published in 2009 concluded that acupuncture was at least as effective as, or possibly more effective than, preventive drug treatment for migraine prophylaxis with fewer side effects compared with conventional treatments.36 However, there is a lack of adequately powered evidence to prove the effect and safety of acupuncture for acute migraine attacks in adults.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to assess if acupuncture is effective and safe in relieving headache, preventing relapse and reducing migraine-associated symptoms for the treatment of acute migraine attacks in adults. The following comparisons will be addressed:

Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, placebo or no treatment.

Acupuncture versus pharmacological therapies.

Methods and analysis

Types of studies

We will include randomised controlled trials (RCTs) using acupuncture to treat a migraine headache episode. Quasi-RCTs will be excluded. The first period of randomised cross-over trials will be included.

Types of participants

Adults diagnosed with migraine (according to the definition of the Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society) will be eligible for inclusion. Studies where participants are receiving stable migraine prophylactic treatment will be included. There will be no restrictions on migraine type (eg, migraine with aura, migraine without aura), duration of migraine, frequency of attack or pain intensity.

Types of intervention

Interventions in the treatment group will include manual acupuncture, electroacupuncture, scalp acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, eye acupuncture, fire needling, warm needling and elongated needling. There will be no duration restrictions on the intervention. Comparison interventions include sham acupuncture, placebo, no treatment or pharmacological therapies. Trials evaluating acupuncture plus another treatment versus the same other treatment alone will be included. Those trials comparing different forms of acupuncture and those evaluating prophylaxis effect will be excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Pain-free (pain score=0) at 2 h after the treatment, without the use of rescue medication.37

Study data from scales measuring pain intensity as an outcome will be included, such as the visual analogue scale, Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Verbal Rating Scale (VRS).37 38

Secondary outcomes

Headache relief (a decrease in headache from severe or moderate to none or mild within 2 h, before any rescue medication).

Sustained pain freedom (pain free at 2 h with no use of rescue medication or relapse within the subsequent 46 h).

After 2 h pain freedom, any headache pain from 2 to 48 h after study drug administration, regardless of its severity, is considered a relapse or recurrence.

Incidence of relapse (recurrence).

Adverse events.

Migraine-associated symptoms (nausea, photophobia, phonophobia).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We will search MEDLINE (OVID), EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and four Chinese databases (Chinese Biomedical Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database and Wanfang Database) from inception to February 2015. Any relevant ongoing or unpublished trials will also be searched on the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled-trials.com), the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://www.who.int/trialsearch). We will only include trials reported in English and Chinese. The search strategy for MEDLINE is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy used in MEDLINE (OVID) database

| Number | Search terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | randomized controlled trial.pt. |

| 2 | controlled clinical trial.pt. |

| 3 | randomized. ab. |

| 4 | randomised. ab. |

| 5 | placebo. ab. |

| 6 | randomly. ab. |

| 7 | trial. ab. |

| 8 | or/1–7 |

| 9 | exp migraine disorders |

| 10 | exp acupuncture therapy, or acupuncture |

| 11 | acupuncture. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 12 | manual acupuncture. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 13 | electroacupuncture. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 14 | scalp acupuncture. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 15 | auricular acupuncture. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 16 | eye acupuncture. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 17 | fire needling. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 18 | warm needling, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 19 | elongated needling ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 20 | or/10–20 |

| 21 | 8 and 9 and 20 |

This search strategy will be modified as required for other electronic databases.

Other sources

The reference lists of retrieved articles and related conference proceedings will also be searched for any relevant RCTs that were not identified during the database searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

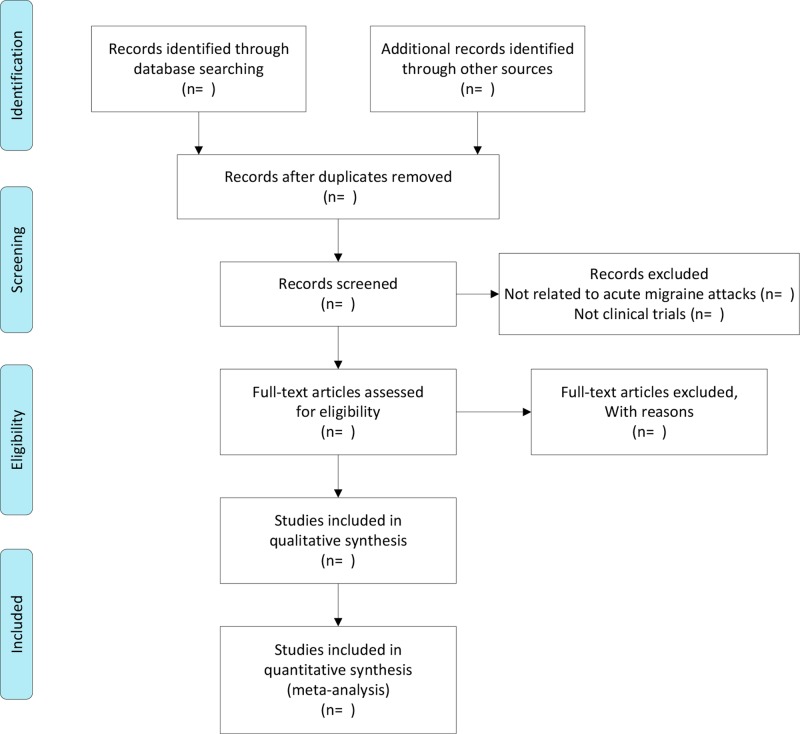

Prior to the selection of the studies, a consensus on screening and later procedures will be developed by discussion among all reviewers. Literature search results will be uploaded to a database set up by EndNote software (V.X6). The screening of studies will be carried out by two independent reviewers (RD and XL). Reviewers will read the titles, abstracts and full texts (if necessary) of the search results to select studies suitable for inclusion. Results of each reviewer will be compared to determine final eligibility, with discrepancy resolved via discussion with a third reviewer (ZL). The study screening process is shown in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the trial selection process.

Data extraction and management

Using a data extraction form (Excel), reviewers will extract information on the author, year of publication, country, participant characteristics, methods, interventions and outcomes, and adverse events. Data will be cross-checked between reviewers (RD and XL) with discrepancies resolved with discussion. For unresolved discrepancies, final determination from a third reviewer will be sought (ZL). Additional information from corresponding authors of the included studies will be requested in circumstances where the published data are unclear, contain errors, are missing or require further clarification.

Assessment of risk of bias

Two independent reviewers (RD and XL) will assess the risk of bias for each included RCT using the Cochrane Collaboration's ‘Risk of bias’ tool.39 Study bias will be classified as either: ‘unclear’, ‘low’ or ‘high’ risk for the following criteria: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data, selective outcome reporting and other bias. Discrepancies in the ratings between the primary reviewers will be resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (ZL). We will compute graphic representations of potential bias within and across studies using RevMan V.5.3.5.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, data will be analysed using the risk ratio with 95% CIs. For continuous outcomes, the weighted mean difference (WMD) or the standard mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI will be used. If the same measurement scales are used, WMD analyses will be performed; otherwise, SMD will be used.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis will be the individual participant.

Dealing with missing data

If necessary data are missing, we will try to get the information by contacting the first or corresponding authors of the included studies. If the missing data cannot be obtained, we will analyse the available data. When possible, a sensitivity analysis will be conducted to address the potential impact of missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The Q statistic from the χ2 test and the I2 value will be used to quantify statistical heterogeneity. According to the Cochrane Handbook, Q is considered statistically significant if p<0.10. The I2 value is classified into four categories: 0–40% indicates little or no heterogeneity; 30–60% indicates moderate heterogeneity; 50–90% indicates substantial heterogeneity and 75–100% indicates considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there are at least 10 included trials, funnel plots will be generated to estimate reporting biases.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis will be conducted using Review Manager (V.5.3.5) from the Cochrane Collaboration. If the heterogeneity test shows little or no heterogeneity, the fixed effect model will be used for pooled data. The random effect model will be adopted if statistical heterogeneity is observed (I2≥50%). If there is considerable variation in results, and particularly if there is inconsistency in the direction of effect, then the meta-analysis will not be performed; a narrative, qualitative summary will be provided.39

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis can explore and assess the heterogeneity. If the data are available, we will conduct subgroup analysis according to different types of acupuncture therapies.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis can assess the stability and reliability of the analysis results and restrict analysis to a low risk of bias. The analysis will be repeated by removing the impact of lower quality studies, inputting missing data or choosing a different method of meta-analysis.

Summary of evidence

We will assess the quality of evidence for all outcomes using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.39 The following factors will be considered: limitations in the design and implementation of available studies suggesting a high likelihood of bias, indirectness of evidence, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results, imprecision of results and high probability of publication bias. The quality of evidence will be adjudicated into four levels: high, moderate, low and very low quality.

Discussion

This systematic review will evaluate published RCT evidence for the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture for acute migraine attacks in adults. In addition, it may assist clinician clinical treatment for migraine with potential to influence future recommendations of treatment guidelines. The proposed review is limited to English and Chinese publications. This limitation may reduce the significance of the review's results and any subsequent conclusions that may be formed. If we need to amend this protocol, we will give the date of each amendment, a description of the change and the rationale.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Weina Peng for reviewing this manuscript.

Contributors: ZL is the guarantor. RD and ZL contributed to the conception of the study. The manuscript of the protocol was drafted by RD and was revised by ZL and YW. The search strategy was developed by all authors and will be run by RD and XL, who will also independently screen the potential studies, extract data of included studies, assess the risk of bias and finish data synthesis. ZL will arbitrate the disagreements and ensure that no errors occur during the study. All authors have approved the publication of the protocol.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013;33:629–808. 10.1177/0333102413485658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claudia F, Heidi G, Lyn R. Studies on the pathophysiology and genetic basis of migraine. Curr Genomics 2013;14:300–15. 10.2174/13892029113149990007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noseda R, Burstein R. Migraine pathophysiology: anatomy of the trigeminovascular pathway and associated neurological symptoms, CSD, sensitization and modulation of pain. Pain 2013;12,154 (Suppl 1):1–21. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietrobon D, Moskowitz MA. Pathophysiology of migraine. Annu Rev Physiol 2013;75:365–91. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO). How common are Headaches? http://www.who.int/features/qa/25/en/ (accessed 30 Aug 2014).

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO). Lifting the Burden: Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/atlas_headache_disorders/en/ (accessed 30 Aug 2014).

- 7.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M et al. Years lived with disability (YLD) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2163–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edmeads J, Findlay H, Tugwell P et al. Impact of migraine and tension-type headache on lifestyle, consulting behaviour, and medication use: a Canadian population survey. Can J Neurol Sci 1993;20:131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freitag FG. The cycle of migraine: patients’ quality of life during and between migraine attacks. Clin Ther 2007;29:939–49. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart WF, Lipton RB. The economic and social impact of migraine. Eur Neurol 1994;34:12–17. 10.1159/000119527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg L. The cost of migraine and its treatment. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:S62–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munakata J, Hazard E, Serrano D et al. Economic burden of transformed migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache 2009;49:498–508. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01369.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ et al. The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:703–11. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03612.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simona S, Tobias K. Migraine and the risk for stroke and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2014;16:524–31. 10.1007/s11886-014-0524-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME et al. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2009;339:b3914 10.1136/bmj.b3914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jerusa AA, Jayme M, Xavier C. Acupuncture in migraine prevention: a randomized sham controlled study with 6-months posttreatment follow-up. Clin J Pain 2008;24:98–105. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181590d66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Von PS, Ting W, Scrivani S et al. Survey on the use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with headache syndromes. Cephalalgia 2002;22:395–400. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baischer W. Acupuncture in migraine: long-term outcome and predicting factor. Headache 1995;35:472–4. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3508472.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pintov S, Lahat E, Alstein M et al. Acupuncture and the opioid system: implications in management of migraine. Pediatr Neurol 1997;17:129–33. 10.1016/S0887-8994(97)00086-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allais G, Lorenzo C, Quirico PE et al. Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache 2002;42:855–61. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vickers A, Rees RW, Zollman CE et al. Acupuncture for chronic headache in primary care: large, pragmatic, randomized trial. BMJ 2004;328:744–50. 10.1136/bmj.38029.421863.EB [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linde K, Streng A, Jurgens S et al. Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:2118–25. 10.1001/jama.293.17.2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burke A, Upchurch DM, Dye C et al. Acupuncture use in the United States: findings from the National Health Interview Study. J Altern Complement Med 2006;12:639–48. 10.1089/acm.2006.12.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference. Acupuncture. JAMA 1998;280:1518–24. 10.1001/jama.280.17.1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.China Association for the Study Pain (CASP). China diagnosis and management of migraine. Chin J Pain Med 2011;17:83. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapoport AM. The therapeutic future in headache. Neurol Sci 2012;33(Suppl 1):S119–25. 10.1007/s10072-012-1056-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao ZQ. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol 2008;85:355–75. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han JS. Acupuncture and endorphins. Neurosci Lett 2004;361:258–61. 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griggs C, Jensen J. Effectiveness of acupuncture for migraine: critical literature review. J Adv Nurs 2006;54:491–501. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evers S, Afra J, Frese A et al. European Federation of Neurological Societies. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine—revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:968–81. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Todd AS, Rebecca B, Huma S et al. The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches in the United States: a review of statistics from national surveillance studies. Headache 2013;53:427–36. 10.1111/head.12074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rapoport AM, Tepper SJ, Bigal ME et al. The triptan formulations: how to match patients and products. CNS Drugs 2003;17:431–47. 10.2165/00023210-200317060-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapoport AM, Tepper SJ. Triptans are all different. Arch Neurol 2001;58:1479–80. 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tfelt-Hansen P, Olesen J. Taking the negative view of current migraine treatments: the unmet needs. CNS Drugs 2012;26:375–82. 10.2165/11630590-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peer TH. What efficacy measures are clinically relevant and should be used in Cochrane reviews of acute migraine trials? A viewpoint. Cephalalgia 2015;35:457–9. 10.1177/0333102414545347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B et al. Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD001218 10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: third edition. A guide for investigators. Cephalalgia 2012;32:6–38. 10.1177/0333102411417901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loder E, Burch R. Measuring pain intensity in headache trials: which scale to use? Cephalalgia 2012;32:179–82. 10.1177/0333102411434812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic review of intervention version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed 16 Dec 2014). [Google Scholar]