Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness of toolkits as a knowledge translation (KT) strategy for facilitating the implementation of evidence into clinical care. Toolkits include multiple resources for educating and/or facilitating behaviour change.

Design

Systematic review of the literature on toolkits.

Methods

A search was conducted on MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL. Studies were included if they evaluated the effectiveness of a toolkit to support the integration of evidence into clinical care, and if the KT goal(s) of the study were to inform, share knowledge, build awareness, change practice, change behaviour, and/or clinical outcomes in healthcare settings, inform policy, or to commercialise an innovation. Screening of studies, assessment of methodological quality and data extraction for the included studies were conducted by at least two reviewers.

Results

39 relevant studies were included for full review; 8 were rated as moderate to strong methodologically with clinical outcomes that could be somewhat attributed to the toolkit. Three of the eight studies evaluated the toolkit as a single KT intervention, while five embedded the toolkit into a multistrategy intervention. Six of the eight toolkits were partially or mostly effective in changing clinical outcomes and six studies reported on implementation outcomes. The types of resources embedded within toolkits varied but included predominantly educational materials.

Conclusions

Future toolkits should be informed by high-quality evidence and theory, and should be evaluated using rigorous study designs to explain the factors underlying their effectiveness and successful implementation.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review on toolkits critically appraises research on strategies to facilitate practice change among health professionals.

Results highlight the importance of evaluating implementation outcomes in addition to behavioural and clinical outcomes.

This review was limited by a lack of an accepted definition for the term toolkit.

Introduction

Knowledge translation (KT) is a complex process occurring between researchers and knowledge users that includes the “synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health…provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system.”1 The degree of engagement in the KT process may be influenced by factors such as the research results and needs of the knowledge user.1 Clinical practice audits have demonstrated that health professionals do not consistently or effectively use current and high-quality research evidence as a basis for clinical care.2 Despite strategies to facilitate the process of implementing research into practice, such as the development and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines, a major disconnect remains between evidence-based practice and actual clinical practice.3

Evidence-based KT strategies for linking research evidence and clinical practice include but are not limited to printed educational materials, educational meetings, educational outreach, the use of local opinion leaders, audit and feedback, and reminders.3 These strategies have been used alone as single KT intervention or as multifaceted KT interventions, which consist of two or more strategies or variations of the same strategies (eg, educational materials) delivered in combination to change practice.4–6 The benefit of multifaceted versus single KT interventions to change clinical and practice outcomes remains unclear, with some investigators reporting they are no more effective.4 7 8

A variation on multifaceted KT interventions is the toolkit. Toolkits offer greater flexibility of use, and for the purposes of this review, are defined as a packaged grouping of multiple KT tools and strategies that codify explicit knowledge (eg, templates, pocket card guidelines, algorithms), and are used to educate and/or facilitate behaviour change.9 Use of KT strategies housed within a toolkit are not necessarily prescribed in any combination or temporality (eg, Strategy A+/or Strategy B+/or Strategy C, etc). The goal is for the user to select KT strategies in the toolkit that are supported by evidence of effectiveness and for use at their own discretion, according to their aims, resources and context. Toolkits differ from multifaceted interventions in which the coupling of more than one KT strategy must be implemented together to comprise the ‘KT intervention’; for example, Strategy A+Strategy B=multifaceted KT strategy.

Evidence-based toolkits can be used to facilitate practice change, and can include strategies for guideline implementation, informing policy, practitioner training, and provide quality audit materials.10 11 Currently, a wide range of toolkits address various clinical disease entities, such as diabetes and cancer care. For instance, the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario offers a toolkit on Best Practice Guidelines for patient care.12 Despite the uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of multifaceted KT interventions, organisations are investing resources in the development of KT toolkits because they provide a simple, more flexible and expedient method for promoting and utilising best healthcare practices. Whether these toolkits or their components are effectively implemented and positively associated with clinical outcomes remains unknown.

Toolkits comprise KT strategies that can be effective in supporting a range of KT aims if they are based on a clear rationale, quality evidence of their effectiveness, supported by a conceptual framework and built on a careful assessment of contextual barriers.3 To be effective, toolkits should also provide high-quality evidence to guide their use or implementation. Currently, little is known about the effectiveness, feasibility and acceptability of toolkits. The aim of this systematic review was to identify and evaluate the effectiveness of toolkits for facilitating the implementation of evidence into clinical care and to inform future development, implementation and evaluation of toolkits.

Methods

The methods for this review were based on the PRISMA checklist (http://www.prisma-statement.org/2.1.2%20-%20PRISMA%202009%20Checklist.pdf).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search of four electronic databases, MEDLINE (1946–November 2013), EMBASE (1947–November 2013), PsycINFO (1806–November 2013) and CINAHL (1981–November 2013), was conducted by a library information specialist. Search terms included database subject headings and text words for the following concepts: toolkits or toolboxes; evaluation, adherence or outcome assessment; and hospitals and hospitalised patients. The evaluation search terms used in MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO were based on published optimised search strategies.13–15 CINAHL evaluation terms were based on the optimised MEDLINE strategy. No date, age or language limits were applied (see online supplementary appendix).

Study selection

Study selection was conducted in two stages. First, all titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (Winnie Lam and Tissari Hewaranasinghage). To establish inter-rater reliability of study selection, each reviewer pilot tested 10 studies using the inclusion criteria. There was 95% agreement on the selected review articles. If necessary, a third reviewer (AS) who was not involved in the selection process resolved any disagreements. In the second stage, the full texts of all selected studies were screened to assess study eligibility and determine the final list of included studies.

Studies were included if: (1) they evaluated the effectiveness of a toolkit to support the integration of evidence into clinical care, either alone or embedded within a larger multistrategy intervention (toolkit +); (2) the KT goals(s) were to inform, share knowledge, build awareness, change practice, change behaviour (in the public), and/or clinical outcomes in healthcare settings, inform policy, or to commercialise an innovation; and (3) they included a comparison group. Studies published in languages other than English, thesis dissertations and studies published in non-peer-reviewed journals or in abstract form only were excluded. All study designs were included. Reference lists from included papers were screened for additional studies.

Methodological quality ratings

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project's (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies.16 The EPHPP assesses methodological quality in systematic reviews of effectiveness.17 Reliability and content and construct validity of the tool have been established.18

The EPHPP tool can be used to evaluate multiple study designs that include comparison groups. Six categories, each consisting of a series of questions, are used to rate each study: (1) selection bias (two questions); (2) study design (four questions); (3) confounders (two questions); (4) blinding (two questions); (5) data collection methods (two questions) and (6) withdrawals and drop-outs (two questions). Each category is then assigned a rating (strong, moderate or weak), and based on these individual category ratings, a global rating is assigned for the study (strong, moderate or weak). Additionally, the integrity of the study intervention and analyses is also examined; however, they do not contribute to the overall global rating.16

All studies were rated independently by two reviewers (AS and JY) using the EPHPP tool. Prior to rating the studies, the tool was pilot tested on 10 studies. Overall per cent agreement was 88.5% (κ=0.84, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.96). When necessary, consensus meetings were held between reviewers to compare results and reach agreement on all studies. A third reviewer (KW) who was not involved in the quality assessment process resolved any disagreements.

Data extraction and analysis

Utilising a standardised data extraction chart, three reviewers (AS, KW and JY) independently extracted the following data from the studies that received a strong or moderate methodological global rating: study type, type of study participants, toolkit content, KT strategy and clinical outcome measures, including implementation outcomes as defined by Proctor et al19 (ie, acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration and sustainability) and study results. Because many studies embedded the toolkit into a multistrategy intervention (ie, toolkit plus an additional KT strategy(ies)) and did not evaluate the toolkit alone, information regarding all of the components of the KT intervention was extracted. As well, the type of evidence, if any, underpinning the toolkits’ contents (KT strategies, tools) was extracted.

To determine toolkit effectiveness, Lugtenberg et al’s20 method was adopted to assign outcomes from each toolkit to one of three categories: (1) not effective (if no significant effects were demonstrated); (2) partially effective (if half or less of the outcome measures showed significant effects) or (3) mostly effective (if more than half the outcome measures showed significant effects). When study outcomes could not be at least partially attributed to the toolkit (eg, the toolkit was used in the multistrategy intervention and the control group), the study was excluded from detailed reporting.

If similar data from studies were available (eg, means, SDs, proportions), meta-analyses would be conducted. A weighted mean difference, or a standardised mean difference, relative risk, risk difference all with 95% CIs would be conducted using a fixed effects model. If pooling of results would not be possible, a narrative descriptive review of study results would be presented.

Results

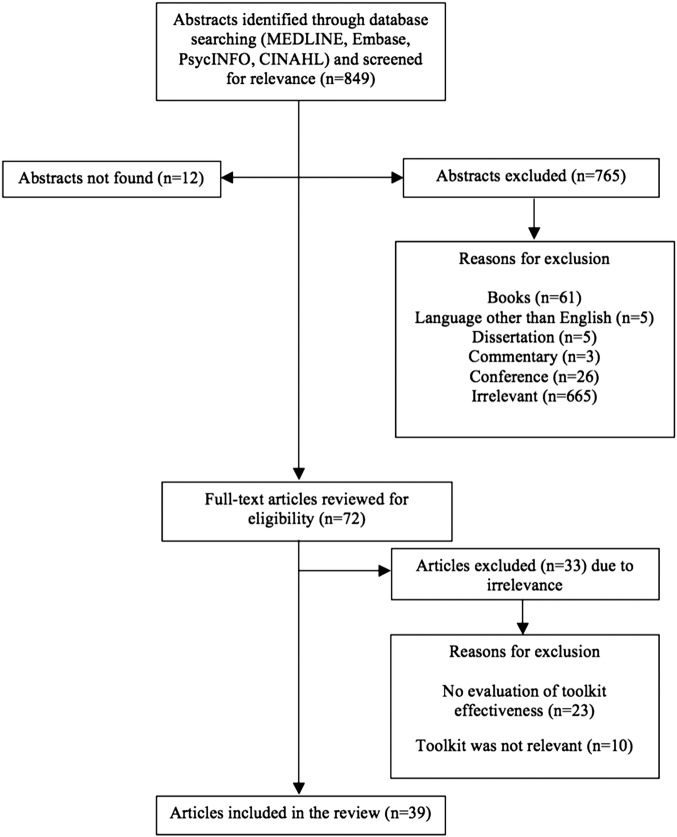

The search strategy yielded 39 unique studies for inclusion in this review11 21–58 (figure 1). Given the diversity of studies in terms of participants and outcomes, a meta-analysis was not possible; therefore, we chose to report on all studies with a strong or moderate global ratings rather than focusing only on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of potentially weak quality.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow chart.

The majority of the studies were RCTs (n=11)26 30 33 36 44 45 49 51 53 57 or one-group cohort studies (n=13).21 24 25 27 32 34 37 39 46 50 52 55 58 Eighteen of the included studies had toolkits embedded within a larger multistrategy KT intervention,22 23 26–28 31 32 38 42–45 49 53–55 57 58 and 21 studies evaluated toolkits as standalone KT interventions.11 21 24 25 29 30 33–37 39–41 46–48 50–52 56

Among all of the toolkits, 20 were developed for a specific disease context,21 22 26–28 31–34 40–45 47 51 54 55 57 most commonly for cancer (n=8)27 28 31 40 41 43 54 57 and diabetes (n=3).22 26 51 The remaining toolkits were developed for disease prevention (n=5),23 38 46 52 58 infection prevention (n=2),11 53 postoperative pain (n=1),48 smoking cessation (n=1),49 care in the geriatric population (n=8),24 25 29 30 35 36 39 56 patient safety (n=1)50 and general hospital quality improvement (n=1).37

Toolkits were targeted to health professionals (n=29),11 21 23–27 29–32 35 37–39 42 44–47 49–52 53 55–58 patients (n=10)21 22 28 33 34 40 41 43 48 54 and caregivers (n=1).36 In one study, the intervention included separate toolkits for primary care physicians and patients.18

Only 2611 21 24–32 34 35 37 39–41 43 44 46–51 54 of the included studies specifically indicated the clinical evidence, rationale or theoretical basis underlying the toolkit strategies.

Methodological quality of the studies

The majority of studies (n=26)21–25 27–29 31 32 34 35 37–41 45–48 50 52 55 56 58 were rated as methodologically weak on the EPHPP tool (ie, in terms of study design, selection bias, confounders, blinding, data collection methods and withdrawals and drop-outs); with 8 studies11 26 30 42 44 49 51 53 rated as moderate; and 533 34 43 54 57 as strong. The 13 moderate and strongly rated studies still had some general weaknesses. In 7 of the 13 studies,11 26 30 33 42 44 57 blinding of outcome assessors and/or blinding of study participants to the research question were not explicitly stated. In the selection bias category, only 4 of the 13 studies26 36 44 57 reported the proportion of eligible participants who agreed to participate in the study. As well, in 6 of the 13 studies,11 26 30 36 42 44 raters agreed that the study participants were only somewhat likely, as opposed to very likely to represent the study population, introducing the potential for selection bias.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of the toolkits

In 5 of the 13 moderate to strongly rated studies,11 43 49 53 54 it was not possible to determine if clinical outcomes were attributable to the toolkit because all study participants received the toolkit in some variation. These five studies explored the effectiveness of the toolkit, either alone or paired with minimal additional interventions (multistrategy).A summary of the remaining eight studies is provided in table 1.26 30 33 36 42 44 51 57

Table 1.

Effectiveness of toolkits in strongly and moderately rated studies (N=8)

| Study design, participants | Toolkit and intervention | Evidence informing toolkit development | Outcomes measured | Results | Quality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavanaugh et al26 | Two RCTs at 2 academic medical centres N=198 adult patients with diabetes n=99 (control) n=99 (intervention) Country: USA |

Intervention components: enhanced diabetes care programme; training sessions; DLNET Control components: enhanced diabetes care programme Toolkit target: health professionals Toolkit contents: customisable 24 instructive modules about diabetes self-management activities, including blood glucose monitoring, nutrition management, foot care, administration of medications |

Incorporated communication principles |

|

Significant improvements in A1c levels in intervention and control groups at 3 months (adjusted analyses showed greater improvement in the intervention group (p=0.03)) Significant improvement in self-efficacy from baseline in both groups (p=0.01,0.02) (but NS differences between groups in adjusted analyses) NS differences between intervention and control for self-management behaviour or treatment satisfaction NS differences between intervention and control groups at 6 months Implementation outcomes: sustainability of outcomes measured at 3 and 6 months Toolkit effectiveness: partially effective |

M |

| Dykes et al 30 | Cluster RCT N=8 units in 4 urban US hospitals, N=10 264 patients n=5160 (intervention) n=5104 (control) Country: USA |

Intervention components: FPTK; local champions Control components: usual care Toolkit target: health professionals Toolkit contents: Morse Falls Scale to assess fall risk; interventions tailored to patient-specific areas of risk; bed poster, patient/family education handout, fall prevention plan (tailored for each patient) |

Literature review, focus groups with nurses+nursing assistants, assessment of barriers and facilitators to optimal practice |

|

Significantly fewer patients with falls in intervention versus control units (p=0.02) Significantly lower adjusted fall rates in intervention versus control units per 1000 patient-days (p=0.04) NS difference in fall-related injuries Implementation outcomes: protocol adherence >89% Toolkit effectiveness: mostly effective |

M |

| Majumdar et al42 | Controlled clinical trial N=14 managed care practices Country: USA |

Low-intensity intervention components: evidence-based guideline on Helicobacter pylori; Toolkit High-intensity intervention components: evidence-based guideline on H. pylori; Toolkit; academic detailing of guideline dissemination by a PCP champion using persuasive educational session; 1 month reinforcement of guideline message; and reminder about eligible patients by a pharmacist Control components: usual care Toolkit target: health professionals Toolkit contents: customised list of eligible patients from participating practice; educational materials for patients; patient letters used to arrange for test or follow-up appointment; pre-printed materials including: (A) H. pylori serology test requisitions, (B) preapproved prescriptions, (C) progress notes for patient charts |

Not specified |

|

Significant increase in H. pylori test-ordering in high-intensity intervention versus usual care at 12 months (p=0.02)Significant decrease in proton pump inhibitor use by 9% per year in high-intensity intervention versus usual care (p=0.028) Implementation outcomes: sustainability of outcomes measured at 12 months Toolkit effectiveness: mostly effective |

M |

| Menchetti et al44 | Cluster RCT N=15 primary care groups with 223 PCPs n=8 intervention (128 patients) n=7 control (99 patients) Country: Italy |

Intervention components: 2-day intensive training for PCPs; implementation of a stepped care protocol; dedicated consultant psychiatrist; Depression Management Toolkit Control components: usual care Toolkit target: PCPs Toolkit contents: issues discussed during training with PCPs; diagnostic procedure based on the PHQ-9; treatment algorithm |

Based on training program developed by project steering committee |

|

NS differences between groups in remission of depression at 3, 6, 12 months; however in patients with minor/major depression, intervention was more effective than usual care at 3 months (p=0.015). Intervention group showed significantly higher treatment response rates at 3 (p=0.016) and 6 months (p=0.049). PCP increased use of appropriate antidepressants and decreased use of sedatives, hypnotics at 3 months. Implementation outcomes: sustainability of outcomes measured at 3, 6, 12 months Toolkit effectiveness: partially effective |

M |

| Shah et al51 | Pragmatic Cluster RCT n=933 789 adult patients with diabetes (administrative data study) n=1592 patients with diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular disease (clinical data study) Country: Canada |

Intervention components: toolkit Control components: usual care Toolkit target: family physicians Toolkit contents: introductory letter; tailored 8-page summary of practice guidelines; 4-page synopsis of key guideline elements pertaining to cardiovascular disease risk; small laminated card with simplified algorithm for cardiovascular risk assessment, vascular protection strategies+screening for cardiovascular disease; tear-off sheets for patients with a cardiovascular self-assessment tool; list of recommended risk reduction strategies. Toolkit was packaged in a brightly coloured box with Canadian Diabetic Association branding) |

Clinical experts (family physicians, endocrinologists), clinicians with KT expertise |

|

NS difference between groups in death or non-fatal MI (p=0.07) and use of a statin (p=0.26). Decreased use of ECG (p=0.02) and cardiac stress tests (p=0.04) in intervention group Implementation outcomes: not specified Toolkit effectiveness: not effective |

M |

| Wright et al57 | Cluster RCT N=42 Ontario hospitals (616 patients with stage II colon cancer) Country: Canada |

Intervention components: standardised lecture from expert opinion leader; toolkit; academic detailing of local opinion leader; 6-month follow-up reminder package Control components: standardised lecture from expert opinion leader Toolkit target: physicians Toolkit contents: pathology template; poster and pocket cards emphasising 12 LNs to be assessed in colon cancer |

Not specified |

|

Significant increase in mean number of LNs assessed and the proportion of cases with 12 or more LNs retrieved for both groups after standardised lecture (p<0.001). No additional increase noted with academic detailing and toolkit. Implementation outcomes: not specified Toolkit effectiveness: not effective |

S |

| Goeppinger et al33 | 4 months RCT and 9 months longitudinal study N=921 adults with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia or chronic joint symptoms n=463 (control), n=458 (intervention) Country: USA |

Intervention components: Arthritis Self-Management Toolkit Control components: no intervention Toolkit target: patients with arthritic conditions Toolkits contents (available in English and Spanish): ‘self-test’ to self-tailor the toolkit; information sheets on arthritic-related health issues and on key process components of the Arthritis Self-Management Program (eg, decision-making); Arthritis Help Book; audio relaxation and exercise CDs; audio CD of all material from information sheets |

Not specified |

|

Statistically significant improvement in 6/7 health status measures, all health-related behaviours and self-efficacy but not in medical care utilisation variables at 4 months postintervention (p<0.01) in intervention versus control groups Results maintained at 9 months compared with baseline Implementation outcomes: sustainability of outcomes measured at 9 months 97% of participants reported use of the toolkit and found it useful. The Book was rated the most useful part Toolkit effectiveness: mostly effective |

S |

| Horvath et al36 | RCT N=108 dyads of patients with progressive dementia of Alzheimer's type/caregiver n=48(control) n=60 (intervention) Country: USA |

Intervention components: Home Safety Toolkit Control components: 1 page standard patient education sheet Toolkit target: caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's Toolkit contents: ‘Keep the Home Safe for a Person with Memory Loss’ booklet; low-cost sample items to reduce risky behaviours and accidents |

Principles of health literacy, patient-centred care and self-efficacy |

|

Significantly higher caregiver self-efficacy (p=0.002), significantly lower caregiver strain (p≤0.001), significant improvement in home safety (p≤0.001), significantly fewer risky behaviours and accidents (p≤0.001) in intervention versus control Implementation outcomes: fidelity to protocol achieved Cost of toolkit included but not a cost/benefit analysis Toolkit effectiveness: mostly effective |

S |

DLNET, Diabetes Literacy Numeracy Education Toolkit; FPTK, Fall Prevention Toolkit; LN, lymph node; M, moderate; NS, non significant; PCP, primary care physician; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; RCT, randomised controlled trial; S, strong.

Among the remaining eight studies, three33 36 51 evaluated the toolkit as a single KT intervention against a no KT intervention group, while five26 30 42 44 57 evaluated a multistrategy KT intervention against a no KT intervention group. Only four of five multistrategy intervention studies26 30 42 44 demonstrated partial to mostly effective results. Of the three single KT intervention studies, two33 36 were mostly effective at changing clinical outcomes. Additionally, no studies evaluated the relative effectiveness of each KT strategy (eg, use of audit and feedback); therefore, it was not possible to determine which components contributed to the change in outcomes.

The majority of the studies26 30 33 36 44 51 aimed to evaluate the toolkit's effectiveness for a variety of KT goals. One study focused on changing patient clinical outcomes (eg, myocardial infarction, number of falls); two studies also evaluated change in patient behaviour;26 33 and one evaluated behavioural change in family caregivers.36 Two studies44 51 focused on toolkit effectiveness for changing clinician behaviour in addition to improving patient clinical outcomes, and two studies42 57 were solely focused on improving clinician behaviour.

Implementation outcomes were mentioned in six studies.26 30 33 36 42 44 Dykes et al30 included a process for assessing fidelity of the KT intervention; Goeppinger et al33 examined the adoption, appropriateness and sustainability of the toolkit; Horvath et al36 provided information about the fidelity of the KT intervention and cost of the toolkit but did not conduct a cost/benefit analysis; and Cavanaugh et al,26 Majumdar et al42 and Menchetti et al44 examined the sustainability of improved clinical outcomes over time.

Toolkit content varied across studies. Two studies included self-management toolkits for patients and caregivers with a focus on arthritis33 and Alzheimer's.36 Six studies evaluated toolkits for health professionals on fall prevention,30 gastro-oesophageal reflux,42 depression,44 diabetes26 51 and cancer.57 Toolkit resources included information/handout sheets, posters, pocket guides and educational modules. Wright et al57 included reminder packages for participants comprised of a cover letter from an expert opinion leader, a peer-reviewed article and additional reminder pocket cards. In five studies,26 30 36 44 51 the authors reported that they relied on clinical experts, reviews of the literature or clinical practice guidelines to inform the toolkit components. Dykes et al30 also incorporated an assessment of the barriers and facilitators to optimal practice in falls prevention and designed the toolkit to address the identified barriers.

Discussion

Toolkits, either alone or as part of a multistrategy intervention, hold promise as an effective approach for facilitating evidence use in practice and improving outcomes across a variety of disease states and healthcare settings. There was significant variation in the combination and type of KT strategies contained within the toolkits, a range of diseases for which they were developed, and a variety of intended knowledge users (eg, health professionals or patients/caregivers), all of which contributed to key knowledge gaps.

Most toolkits contained printed educational materials, such as information sheets or guideline summaries, which were intended to fill knowledge gaps. Although feasible and relatively inexpensive, Giguère et al59 reported that printed educational materials tend to have little to no influence on health professional behaviour, and uncertain effects on patient behaviour. Additional efforts are required to ensure that knowledge users actively engage with toolkit materials, moving away from passive diffusion. Wright et al57 utilised reminders within the toolkit. The effects of computer reminders have demonstrated small to moderate benefits; however, further research is needed on other types of reminders, perhaps utilising social media strategies.60 There is currently no definitive evidence for the ideal combination or number of KT strategies and tools that should be used in toolkits. A planful approach (ie, need to identify the KT goal that is being addressed by the toolkit strategy) including evidence-based KT strategies, tailored and planful implementation support, active engagement, and evaluation of KT impacts that include implementation outcomes should be considered for achieving intended KT goals with the targeted audience.

Better understanding of toolkit effectiveness requires more thorough descriptions of the embedded KT strategies/components and how each individual component contributes to study outcomes. Toolkit descriptions and the contents of the eight moderate and strongly rated studies were brief. Dobbins et al61 suggested that use of multiple KT interventions may weaken the key message of the clinical content when compared with single KT intervention strategies, and the same may be true for toolkits. To minimise this potential weakness, each component within the toolkit should have a purpose and rationale3 that is clearly described for toolkit users.

Toolkit components should be based on high-quality evidence, particularly when the goal is to change practice;3 rationale for their inclusion in the toolkit, given the toolkit aims; and guidance on the implementation process62—how they are to be used. Although the eight studies in this review mentioned some form of evidence underlying each component, descriptions were vague and non-descriptive, and few mentioned high-quality evidence, such as systematic reviews. Often, evidence was provided for only one component of the toolkit. Cavanaugh et al26 used communication theory to design the ‘Diabetes Literacy and Numeracy Education Toolkit’, and did not specify any underlying evidence for their content. Shah et al,51 however, provided evidence for using educational materials as a resource within their educational toolkit, which focused on cardiovascular disease screening and risk reduction in patients with diabetes. Nevertheless, their content was not based on a barriers assessment, quality improvement or educational theory.51

Multiple barriers have been identified to account for the knowledge to practice gap, and many are intrinsic to health professionals and their practice environment or context. For example, organisational constraints, such as lack of time or an inability to access resources, are common barriers to KT.2 LaRocca et al63 suggested that the more successful KT intervention strategies were those that were accessible and could be tailored to the needs and preferences of the users. Components of the fall prevention toolkit by Dykes et al30 included patient/family education handouts that were tailored by the nurse based on the knowledge of the patient, thereby capitalising on high tension for change; adaptability, strength and quality of the intervention; and low complexity.64 The effects of tailoring strategies to address identified barriers to change require more clarity, but may improve care and patient outcomes,65 particularly when KT approaches can capitalise on what we know works in implementation.64 Only one of the eight reviewed studies30 assessed barriers and facilitators to inform the toolkit's components.66 Furthermore, determining the influence of modifiable components of context (eg, leadership support, culture, evaluation) would further allow for customisation of KT strategies to facilitate practice change and clinical outcomes.67 Further research is needed on how the toolkit was developed, and the influence of the practice context as these factors may influence study outcomes.

Consideration should also be given to factors implicated in successful implementation.64 Proctor's taxonomy for implementation outcomes19 was extracted from studies where possible, as these outcomes could be used to indicate successful implementation of the toolkit within the healthcare system. Developing toolkits supported by implementation guidance would go a long way in demonstrating how toolkits contribute to good clinical and implementation outcomes. Descriptions of most toolkits lacked details about the implementation process and outcomes. Evidence Based Practice for Improving Quality (EPIQ)68 is an example of a KT intervention that combines evidence, continuous quality improvement, an implementation process and assessment of implementation outcomes. In phase 1 (Preparation), the hospital unit identifies an implementation team, who are trained to review existing unit pain practices, guidelines and research evidence to inform targeted practice changes. In phase 2 (Implementation), the team identifies specific pain practice aims and KT strategies (eg, educational outreach, reminders and audit and feedback) to implement using quality improvement cycles. EPIQ was effective in improving pain process outcomes (ie, pain assessment and management) and reducing the odds of having severe pain by 51%.5

Only two studies reported on fidelity of toolkit implementation. To be clinically effective, healthcare interventions need to be effectively implemented. Yet, implementation outcomes are often overlooked in research and KT practice, creating high potential for type III errors; lack of clarity about whether the intervention or its implementation have been unsuccessful. This type of error can reduce the power to detect significant effects of an intervention.69 Assessing the fidelity of implementing complex interventions addresses type III error and provides evidence of variability in implementation of interventions, which could also contribute to limited effectiveness.70

All eight studies in this review used RCT designs to evaluate toolkit effectiveness. There is a common methodological challenge to RCT studies of KT effectiveness, in that this design could block important contextual factors that now have burgeoning evidence of their importance in successful implementation.64 Caution is required in interpreting which KT strategies are evidence-based, and new studies need to utilise more appropriate mixed methodologies or other types of randomised designs, such as wait listed or stepped-wedged designs, to address what works in implementation of practice changes.71

Several limitations to this systematic review warrant discussion. The term ‘toolkit’ was used in the studies included in this systematic review. However, there is currently no accepted definition for toolkits in existing taxonomies related to quality improvement and behavioural change strategies (eg, Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group). Although we chose a term that had some consistency in the literature, based on the evidence reported in this review, there is no consensus on key content, implementation strategies to promote behavioural change or theoretical approaches that should be included in implementation toolkits. These findings could explain the heterogeneity of the toolkits included in this review. Therefore, capturing all relevant literature was challenging because of the lack of standard terminology used for toolkits. As a result, relevant studies might have been missed by the search. The majority of studies had significant methodological shortcomings and were rated as weak, mostly due to the study designs. One of the limitations was that we focused on studies that evaluated the effectiveness of a toolkit to support the facilitation of evidence into clinical care; therefore, the studies included in this review reported quantitative results.

The literature search was limited to toolkits used in hospital and other clinical settings. Broadening the search to community or public health settings may have yielded additional studies for the review.9

In summary, toolkits have potential as a promising KT strategy for facilitating practice change in healthcare. To fully understand their effectiveness, a systematic approach to planning and reporting their development, the evidence underlying each component, and any direction regarding appropriate implementation is required. Toolkits should have (1) a clearly described purpose, rationale for each component; (2) components that are rigorously developed and informed by high-quality evidence, such as systematic reviews; (3) delivery methods that are guided by a comprehensive implementation process (eg, self-directed, facilitation, reminders) with consideration for fidelity of implementation where appropriate; and (4) a rigorous evaluation plan and study design that can help explain the factors underlying their effectiveness and successful implementation (ie, combining outcome and process measures including context).9

Only a few of the toolkits in this review met all of these criteria.33 51 Ideally future studies of toolkit effectiveness should also be informed by a theoretical approach. In conclusion, this study provides some evidence for the utility of the toolkit.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Thomasin Adams-Webber, librarian, for her assistance with the systematic literature search. The authors would also like to thank Ms Kamila Rentel for participating in an early review of the articles, and Ms Winnie Lam and Ms Tissari Hewaranasinghage for their assistance with screening articles for relevance.

Footnotes

Contributors: JY led the writing of the manuscript, organised all aspects of the systematic review, participated in the screening of abstracts, rating of methodological quality, data extraction and analysis. She also drafted the initial manuscript, made revisions and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AS participated in the rating of methodological quality, data extraction, and analysis of articles included in the review. She also participated in drafting the initial manuscript and revisions. MB provided guidance and expertise in the overall conceptualisation of the review, revised and critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. KW participated in reviewing the methodological quality, data extraction and analysis of all articles included in the report. She also participated in drafting the initial manuscript and revisions. BS provided guidance and expertise in the overall conceptualisation of the review, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. About knowledge translation & commercialization. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html (accessed 1 Oct 2014).

- 2.Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID. Knowledge translation: what it is and what it isn't. In: Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID eds. Knowledge translation in health care. 2nd edn. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2013:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN et al. . Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci 2012;7:1–17. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Squires JE, Sullivan K, Eccles MP et al. . Are multifaceted interventions more effective than single-component interventions in changing health-care professionals’ behaviours? An overview of systematic reviews. Implement Sci 2014;9:152 10.1186/s13012-014-0152-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens BJ, Yamada J, Carole A et al. . Pain in hospitalized children: effect of a multidimensional knowledge translation strategy on pain process and clinical outcomes. Pain 2014;155:60–8. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada J, Stevens B, Sidani S. Test of a process evaluation checklist to improve neonatal pain practices. West J Nurs Res 2014:0193945914524493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakkennes S, Dodd K. Guideline implementation in allied health professions: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:296–300. 10.1136/qshc.2007.023804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G et al. . Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:iii–iv, 1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barac R, Stein S, Bruce B et al. . Scoping review of toolkits as a knowledge translation strategy in health. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014;14:6 10.1186/s12911-014-0121-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torrey WC, Drake RE, Dixon L et al. . Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:45–50. 10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wirtschafter DD, Powers RJ, Pettit JS et al. . Nosocomial infection reduction in VLBW infants with a statewide quality-improvement model. Pediatrics 2011;127:419–26. 10.1542/peds.2010-1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Registered Nurses’ Association Ontario. Nursing best practice guidelines. http://rnao.ca/bpg (accessed 1 Oct 2014).

- 13.Eady AM, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. PsycINFO search strategies identified methodologically sound therapy studies and review articles for use by clinicians and researchers. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:34–40. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong SS, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound treatment studies in EMBASE. J Med Libr Assoc 2006;94:41–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang L, Ajiferuke I, Sampson M. Optimizing search strategies to identify randomized controlled trials in MEDLINE. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:23 10.1186/1471-2288-6-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html (accessed Aug 2014).

- 17.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R et al. . Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess 2003;7:iii–x, 1–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M et al. . A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2004;1:176–84. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R et al. . Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Westert GP. Effects of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on quality of care: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:385–92. 10.1136/qshc.2008.028043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bender BG, Dickinson P, Rankin A et al. . The Colorado Asthma Toolkit Program: a practice coaching intervention from the High Plains Research Network. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24:240–8. 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benedetti R, Flock B, Pedersen S. Improved clinical outcomes for fee-for-service physician practices participating in a diabetes care collaborative. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2004;30:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Britto MT, Pandzik GM, Meeks CS et al. . Combining evidence and diffusion of innovation theory to enhance influenza immunization. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006;32:426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byszewski AM, Graham ID, Amos S et al. . A continuing medical education initiative for Canadian primary care physicians: the driving and dementia toolkit: a pre-and postevaluation of knowledge, confidence gained, and satisfaction. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1484–9. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51483.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carroll DL, Dykes PC, Hurley AC. An electronic fall prevention toolkit: effect on documentation quality. Nurs Res 2012;61:309–13. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31825569de [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavanaugh K, Wallston KA, Gebretsadik T et al. . Addressing literacy and numeracy to improve diabetes care: two randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2009;32:2149–55. 10.2337/dc09-0563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crogan NL, Evans BC, Bendel R. Storytelling intervention for patients with cancer: part 2—pilot testing. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:265–72. 10.1188/08.ONF.265-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Decker V, Spoelstra S, Miezo E et al. . A pilot study of an automated voice response system and nursing intervention to monitor adherence to oral chemotherapy agents. Cancer Nurs 2009;32:E20–9. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b31114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dedhia P, Kravet S, Bulger J et al. . A quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1540–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley A et al. . Fall prevention in acute care hospitals: a randomized trial. JAMA 2010;304:1912–18. 10.1001/jama.2010.1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans BC, Crogan NL, Bendel R. Storytelling intervention for patients with cancer: part 1—development and implementation. Oncol Nurs Forum 2008;35:257–64. 10.1188/08.ONF.257-264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gannon M, Qaseem A, Snow V. Using online learning collaboratives to facilitate practice improvement for COPD: an ACPNet pilot study. Am J Med Qual 2011;26:212–19. 10.1177/1062860610391081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goeppinger J, Lorig KR, Ritter PL et al. . Mail-delivered arthritis self-management tool kit: a randomized trial and longitudinal follow up. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:867–75. 10.1002/art.24587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg JO, Wheeler H, Lubinsky T et al. . Cognitive coping tool kit for psychosis: development of a group-based curriculum. Cogn Behav Pract 2007;14:98–106. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasson H, Arnetz JE. The impact of an educational intervention for elderly care nurses on care recipients’ and family relatives’ ratings of quality of care: a prospective, controlled intervention study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:166–79. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horvath KJ, Trudeau SA, Rudolph JL et al. . Clinical trial of a home safety toolkit for Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2013;2013:913606 10.1155/2013/913606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussey PS, Burns RM, Weinick RM et al. . Using a hospital quality improvement toolkit to improve performance on the AHRQ quality indicators. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2013;39:177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutchinson J, Evans D, Sutcliffe LJ et al. . STIF Competency: development and evaluation of a new clinical training and assessment programme in sexual health for primary care health professionals. Int J STD AIDS 2012;23:589–92. 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeon YH, Govett J, Low LF et al. . Care planning practices for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in residential aged care: a pilot of an education toolkit informed by the Aged Care Funding Instrument. Contemp Nurse 2013;44:156–69. 10.5172/conu.2013.44.2.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lebret T, Coloby P, Descotes JL et al. . Educational tool-kit on diet and exercise: survey of prostate cancer patients about to receive androgen deprivation therapy. Urology 2010;76:1434–9. 10.1016/j.urology.2010.07.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu S, Ercolano E, Siefert ML et al. . Patterns of symptoms in women after gynecologic surgery. Oncol Nurs Forum 2010;37:E133–40. 10.1188/10.ONF.E133-E140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Majumdar SR, Ross-Degnan D, Farraye FA et al. . Controlled trial of interventions to increase testing and treatment for Helicobacter pylori and reduce medication use in patients with chronic acid-related symptoms. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:1029–39. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCorkle R, Jeon S, Ercolano E et al. . Healthcare utilization in women after abdominal surgery for ovarian cancer. Nurs Res 2011;60:47–57. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181ff77e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menchetti M, Sighinolfi C, Di Michele V et al. . Effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in Italy. A randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:579–86. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newhouse RP, Himmelfarb CD, Morlock L et al. . A phased cluster-randomized trial of rural hospitals testing a quality collaborative to improve heart failure care: organizational context matters. Med Care 2013;51:396–403. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318286e32e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nowalk MP, Nutini J, Raymund M et al. . Evaluation of a toolkit to introduce standing orders for influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in adults: a multimodal pilot project. Vaccine 2012;30:5978–82. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patwardhan MB, Matchar DB, Samsa GP et al. . Utility of the advanced chronic kidney disease patient management tools: case studies. Am J Med Qual 2008;23:105–14. 10.1177/1062860607313142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pulver LK, Oliver K, Tett SE. Innovation in hospital quality improvement activities—Acute Postoperative Pain Management (APOP) self-help toolkit audits as an example. J Healthc Qual 2012;34:5–59. 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2012.00207.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarna L, Bialous SA, Ong MK et al. . Increasing nursing referral to telephone quitlines for smoking cessation using a web-based program. Nurs Res 2012;61:433–40. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182707237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schauberger CW, Larson P. Implementing patient safety practices in small ambulatory care settings. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006;32:419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah BR, Bhattacharyya O, Yu CH et al. . Effect of an educational toolkit on quality of care: a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001588 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith PD, O'Halloran P, Hahn DL et al. . Screening for obesity: clinical tools in evolution, a WREN study. WMJ 2010;109:274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Speroff T, Ely EW, Greevy R et al. . Quality improvement projects targeting health care-associated infections: comparing Virtual Collaborative and Toolkit approaches. J Hosp Med 2011;6:271–8. 10.1002/jhm.873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spoelstra SL, Given BA, Given CW et al. . An intervention to improve adherence and management of symptoms for patients prescribed oral chemotherapy agents: an exploratory study. Cancer Nurs 2013;36:18–28. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182551587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trinh NHT, Hagan PN, Flaherty K et al. . Evaluating patient acceptability of a culturally focused psychiatric consultation intervention for Latino Americans with depression. J Immigr Minor Health 2013;16:1271–7. 10.1007/s10903-013-9924-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiechula R, Kitson A, Marcoionni D et al. . Improving the fundamentals of care for older people in the acute hospital setting: facilitating practice improvement using a Knowledge Translation Toolkit. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2009;7:283–95. 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2009.00145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wright FC, Gagliardi AR, Law CH et al. . A randomized controlled trial to improve lymph node assessment in stage II colon cancer. Arch Surg 2008;143:1050–5. 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zgibor JC, Stevenson JA, Rohay JM et al. . Tracking and improving influenza immunization rates in a high-risk Medicare beneficiary population. J Healthc Qual 2003;25:17–27. 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2003.tb01096.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giguère A, Legare F, Grimshaw J et al. . Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:CD004398 10.1002/14651858.CD004398.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A et al. . The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(3):CD001096 10.1002/14651858.CD001096.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dobbins M, Hanna SE, Ciliska D et al. . A randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of knowledge translation and exchange strategies. Implement Sci 2009;4:61 10.1186/1748-5908-4-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rycroft-Malone J. Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS). In: Rycroft-Malone J, Bucknall T eds. Models and frameworks for implementing evidence-based practice: linking evidence to action. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2010:109–35. [Google Scholar]

- 63.LaRocca R, Yost J, Dobbins M et al. . The effectiveness of knowledge translation strategies used in public health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012;12:751 10.1186/1471-2458-12-751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE et al. . Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:1–15. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baker R, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Gillies C et al. . Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;3:CD005470 10.1002/14651858.CD005470.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Legare F, Zhang P. Barriers and facilitators: strategies for identification and measurement. In: Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID, eds. Knowledge translation in health care. 2nd edn Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2013:121–36. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Hutchinson AM et al. . Assessment of variation in the Alberta Context Tool: the contribution of unit level contextual factors and specialty in Canadian pediatric acute care settings. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:251 10.1186/1472-6963-11-251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee SK, Aziz K, Singhal N et al. . Improving the quality of care for infants: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2009;18:469–76. 10.1503/cmaj.081727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mowbray CT, Holter MC, Teague GB et al. . Fidelity criteria: development, measurement, and validation. Am J Eval 2003;24:315–40. 10.1177/109821400302400303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S et al. . A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci 2007;2:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Landsverk J, Hendricks Brown C, Chamberlain P et al. . Design and analysis in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health. New York, NY: Oxford, 2012:225–60. [Google Scholar]