Abstract

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare, potentially fatal condition that can be primary or secondary. Secondary HLH can occur in association with infections, most commonly viral infections, but has also been reported in association with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB). Prompt identification of the underlying cause of HLH is important as it guides treatment decisions. Early initiation of appropriate treatment (eg, anti-TB treatment) reduces morbidity and mortality. We present a case of HLH associated with TB infection. Initial TB investigations were negative and standard combination chemoimmunotherapy for HLH resulted in a limited clinical response. On apparent relapse of HLH, further investigation revealed TB with changes on CT chest, granuloma on bone marrow and eventual positive TB culture on bronchoalveolar lavage. Subsequent treatment with quadruple anti-TB treatment resulted in rapid clinical response and disease remission. We advocate continued monitoring for TB infection in patients with HLH, and prophylaxis or full treatment for those at high risk.

Background

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare, potentially fatal condition in which abnormal activation of the immune system results in haemophagocytosis, inflammation and tissue damage. This results in a variety of signs and symptoms but most commonly fever, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, cytopenias, hyperferritinaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia.

HLH can be either primary (familial) or secondary (sporadic, acquired). Secondary HLH can occur in association with infections, most commonly viral infections, but has also been associated with fungal, parasitic and bacterial infections, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB).1–3

HLH carries a high mortality rate if untreated or treatment is initiated late in the disease process; so early initiation of treatment, even while awaiting confirmation of the diagnosis, is recommended if there is high clinical suspicion.4 Furthermore, early treatment in limiting disease progression and the risk of irreversible tissue damage can increase chances of achieving a good response to treatment.5 Prompt identification of the underlying cause of HLH is also important as it guides treatment decisions, particularly in non-viral infection-associated HLH, which often responds to treatment of the underlying infection.3

Current treatment of primary HLH follows the Histiocyte Society HLH-2004 treatment protocol, which can also be beneficial for patients with secondary HLH.5 This consists of a combination of chemoimmunotherapy agents. However, in cases of secondary HLH in association with non-viral infections, targeted treatment of the infection can be effective in treating the disorder by removing the stimulus for the activation of the immune system. Therefore, early initiation of the appropriate treatment (eg, anti-TB treatment) can reduce morbidity and mortality. A patient may also be able to avoid prolonged treatment with the standard chemoimmunotherapy agents with their associated adverse effects.

We present a case of HLH associated with TB infection. Initial investigations were negative for TB, although a short course of TB treatment was given while investigations were ongoing. Standard combination chemoimmunotherapy for HLH resulted in a limited clinical response and ultimate return of symptoms attributed to HLH. Reinvestigation for the cause of the patient's symptoms and an increasing suspicion of TB, led to initiation of empiric treatment with a full course of quadruple anti-TB therapy resulting in rapid clinical response and disease remission. Investigations (PCR and culture) subsequently confirmed the diagnosis of TB.

While the negative tests on presentation prevent confirmation of TB as the cause of the patient's symptoms and may relate to reactivation following heavy immunosuppression, we advocate continuous suspicion of underlying infection in the management of patients with suspected HLH. Delay in treatment can increase morbidity and mortality both from HLH as well as from the treatment given, particularly if chemoimmunotherapy was not necessarily required.

Case presentation

A 42-year-old Nepalese man presented to the accident and emergency department with a 5-day history of fevers, rigours and myalgia. He had no significant medical history and took no medications. His siblings and non-consanguineous parents were well. He was a non-smoker, a teetotaller and did not use illicit drugs. He had been a resident of the UK for 12 years and had most recently travelled to Nepal 4 months earlier; of note is the fact that he had made contact with a family member with TB in Nepal.

His baseline observations included a temperature of 38.8°C, a blood pressure of 95/52 mm Hg, a heart rate of 114/min (sinus tachycardia on ECG), respiratory rate of 20/min and oxygen saturations were 96% on air. Cardiovascular and respiratory examinations were unremarkable with normal jugular venous pressure, heart sounds and breath sounds with no additional sounds on auscultation. Abdominal examination, however, revealed mild splenomegaly. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy.

Initial investigations revealed normocytic anaemia, haemoglobin 77 g/L (12·5–15 g/L), raised white cell count 15.2×109/L (4·0–11·0×109), raised neutrophil count 13.4×109/L (2·0–7·0×109) and a normal platelet count of 147×109/L (150–400×109). Liver function tests were deranged with mildly raised bilirubin 25 mmol/L (3–17 mmol/L), raised alanine aminotransferase 48 IU/L (10–40 IU/L), raised alkaline phosphatase 372 IU/L (44–147 IU/L); however, albumin was normal at 37 g/L (30–50 g/L). Blood tests also revealed a raised ferritin 168 962 ng/mL (13–300 ng/mL), raised triglycerides 3.84 mmol/L (normal <1.7 mmol/L), raised lactate dehydrogenase 550 IU/L (140–250 IU/L) and raised C reactive protein >156 mmol/L. Renal function and clotting were preserved. A baseline septic screen was negative (chest X-ray clear, urine dipstick negative, blood cultures negative). CT scan of his chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly.

His haemodynamic instability merited rapid escalation to the intensive care unit for inotropic support. He was initially empirically treated with piperacillin/tazobactam and gentamicin with no response. He went on to have multiple courses of antimicrobials (including meropenem, teicoplanin, caspofungin, daptomycin, linezolid and ambisome) but this was of no avail. Repeated blood and urine cultures were negative. A mediastinal lymph node fine-needle aspirate (FNA) did not show evidence of lymphoma or TB; cultures were not undertaken. A peripheral blood TB ELISPOT was negative.

With fevers, splenomegaly, a progressive pancytopenia, raised ferritin and raised fasting triglyceride levels, the patient was noted to satisfy five of the eight second-line criteria required for a diagnosis of HLH.6 A bone marrow biopsy was therefore performed which confirmed the diagnosis, with 1 in 200 cells demonstrating haemophagocytosis.

The underlying pathoaetiology for HLH was unclear and the patient underwent initial screens for both congenital and acquired causes, as outlined in table 1, which were negative.

Table 1.

Initial negative screen for both congenital and acquired forms of HLH

| Immunological screen | Infection screen |

|---|---|

| sCD255 054 pg/mL (<2500 pg/mL) ANA negative ANCA negative RhF <20 |

EBV PCR negative CMV PCR negative (<150) Hepatitis B negative Hepatitis C negative HIV negative TB ELISPOT (peripheral blood) negative Influenza A/B negative Rhinovirus negative Coronavirus negative Adenovirus negative Metapneumovirus negative Enterovirus negative Parechovirus negative Bocavirus negative RSV negative Strongyloides serology negative Bartonella serology negative Chikungunya negative West Nile virus negative Leishmaniasis negative Brucella negative Dengue negative Rickettsia negative Spotted fevers negative Tick-borne encephalitis negative Sandfly fever negative Mycoplasma pneumoniae negative Legionella pneumophila negative (serology and urinary antigen) Chlamydophila pneumoniae negative Leptospira serology negative Antistreptolysin O titre negative |

| Genetic screen | Malignancy screen |

| HLH screen—no primary cause (no pathological mutations of PRF1, UNC13D or STX11 identified) | OGD—gastritis Flexible sigmoidoscopy—nil abnormal detected CT brain—no space occupying lesion CT CAP—mediastinal lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly MRI brain—pontine enhancement (deemed to be secondary to electrolye disturbances during prolonged Intensive care admission). Tumour markers—negative |

ANA, antinuclear antibody; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; CAP, chest abdomen pelvis; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; OGD, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Treatment

With no clear driving pathoaetiology, treatment was started according to the Histiocyte Society HLH-2004 treatment protocol.5 He received etoposide 300 mg twice weekly, for 2 weeks. However, a subsequent worsening pancytopenia resulted in etoposide being withheld for 1 week and restarted for weeks 3 to 9. Ciclosporin was given for 8 weeks; however, this was stopped due to hepatorenal failure (creatinine peaked at 510 μmol/L, alanine transaminase 38 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 293 IU/L) despite a 25% dose reduction. He received a full course of dexamethasone. Given the history of recent exposure to a TB positive contact in Nepal, he was also started empirically on anti-TB treatment despite no definitive evidence of TB on lymph node FNA and a negative peripheral blood TB ELISPOT. Rifampicin was omitted due to hepatorenal failure.

The patient failed to respond to first-line HLH treatment, developing worsening pancytopenia and drug-related hepatic and renal toxicity. Worsening hepatorenal failure also resulted in his anti-TB treatment being stopped after 2 weeks. The patient's clinical state deteriorated to such an extent that he required repeated admissions to intensive care unit for inotropic support and non-invasive ventilation. He became transfusion dependent (red cells and platelets), and required G-CSF to support his neutrophil counts.

Owing to the poor clinical progress, the patient was transferred to a tertiary care centre for alternative treatment options. Following the transfer, he continued to have recurrent culture-negative fevers with persistently raised ferritin (39 805 µg/L) and triglyceride levels (8.77 mmol/L). Second-line treatment consisted of dexamethasone (20 mg once daily) and 5 days of intravenous immunoglobulin (0.4 g/kg daily) with no apparent improvement. He was then started on a 5-day course of alemtuzumab (10 mg daily) and ciclosporin (75 mg twice daily) and this resulted in clinical improvement. His fevers resolved, and there was a fall in his ferritin and triglyceride levels with associated slight improvement in his cytopenias.

He was discharged from hospital on ciclosporin and a reducing course of dexamethasone, but was readmitted 2 weeks later with fevers, sweats, myalgia, left upper quadrant pain and pleuritic chest pain with associated shortness of breath. He had tender hepatosplenomegaly and worsening pancytopenia and he was deemed to have suffered a relapse of his HLH.

The patient began the work up for haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation as treatment for refractory HLH. He had siblings living in Nepal who were HLA-typed in preparation. His brother was found to be a positive match and was flown to the UK for stem cell collection.

The patient was also found to have cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation (CMV PCR 959 copies/mL compared to <150 copies/mL a week before) secondary to his immunosuppression and he was, therefore, started on ganciclovir.

In view of his respiratory symptoms on this presentation, a CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) and high-resolution CT (HRCT) of his chest were performed. Ground-glass shadowing and bilateral cavitating pulmonary nodules were noted. He underwent a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) to obtain samples for cultures and was then started on empiric quadruple anti-TB treatment (rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol). He also had a repeat peripheral blood TB ELISPOT that was now reactive. This prompted a re-examination of his bone marrow from his recent admission and the further cuts taken from the trephine was evidence for the non-caseating granulomatous inflammation that was now identified. He underwent a repeat bone marrow biopsy which also showed epitheliod granulomas (although ZN and PAS stains were negative). Comparison of his initial CT scans with his repeat imaging demonstrated increased mediastinal nodularity in the later scan.

Diagnosis of TB was confirmed from the BAL with positive M. tuberculosis complex PCR and positive TB cultures 2 weeks later.

Outcome and follow-up

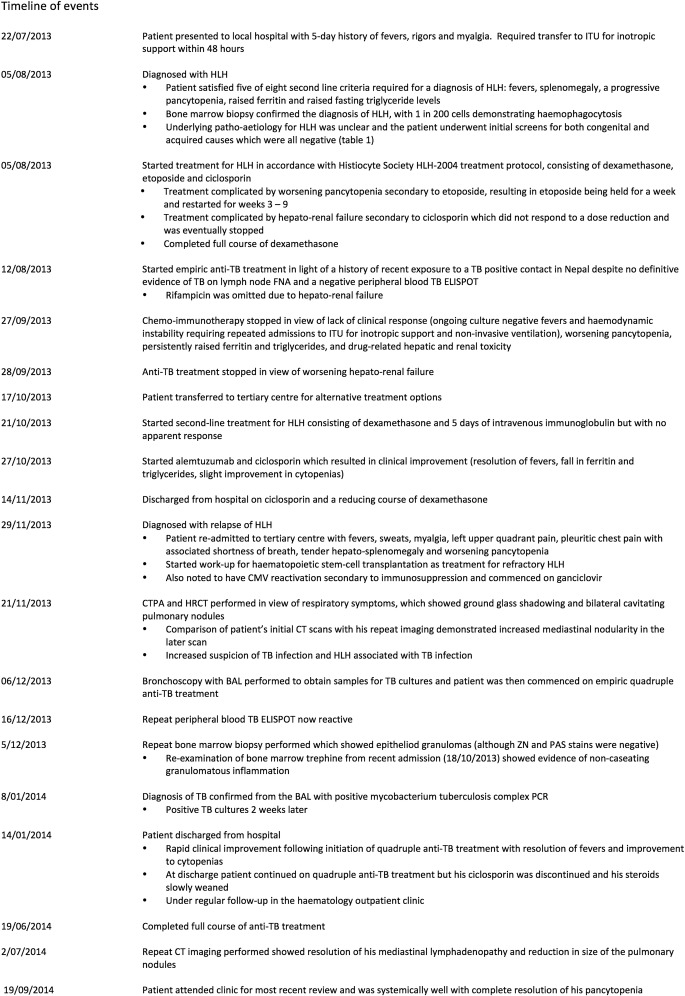

Following initiation of quadruple anti-TB treatment, there was rapid clinical improvement, with resolution of his fevers and improvement to his cytopenias. He was discharged after just over 6 weeks in hospital following his second admission to the tertiary care centre (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline of events.

At discharge, he continued on quadruple anti-TB treatment, but his ciclosporin was discontinued (he received a total of 4 months treatment) and his steroids slowly weaned over a period of a month. He has been regularly followed-up in our outpatient clinic, has remained systemically well and his cytopenias have continued to gradually improve. He has had repeat CT imaging, with his most recent scan performed 6 months following discharge; this showed resolution of his mediastinal lymphadenopathy and reduction in size of the pulmonary nodules.

He completed a full course of anti-TB treatment (a total of 2 months quadruple therapy followed by 4 months of rifampicin and isoniazid as the isolate was fully sensitive). At his last clinical review (which is now 8 months following discharge), he continues to be well and his pancytopenia has resolved. He last required a blood transfusion 1 month following discharge. His most recent ferritin was 1074 µg/L at 6 months postdischarge.

Discussion

HLH is a rare disorder with an estimated incidence of 1/150 000.6 As well as haemophagocytosis, it is characterised by fevers, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, cytopenias, hyperferritinaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, hypofibrinogenaemia, low or absent natural killer (NK) cell activity, and high-soluble CD25 (interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor α) levels.5

The underlying pathophysiology is not fully understood but involves an abnormal activation of the immune system, including macrophages, NK cells and cytotoxic lymphocytes.6 In particular, there is failure of normal autoregulation of NK cell function, increased activation and proliferation of lymphocytes and macrophages, and increased production of cytokines, which ultimately results in uncontrolled haemophagocytosis, excessive inflammation and tissue damage.1 6

HLH can be either primary (familial) or secondary (sporadic, acquired). Primary (familial) HLH, which typically affects young children, refers to HLH caused by an underlying gene mutation. The genetic defects identified affect cytotoxic T lymphocytes and NK cells, and result in dysregulation of normal function.7 Secondary (acquired) HLH, which can occur at any age, occurs in association with infection, malignancy (particularly T-cell lymphoma) and autoimmune disease.

Infections associated with HLH are usually viral, particularly the Epstein-Barr virus.1 However, HLH has also been associated with bacterial, fungal and parasitic infections.2 3 The pathophysiology of infection-associated HLH is not fully understood but increased cytokine production, such as from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected T lymphocytes, is thought to play a role.3 In addition, it has been noted that there is an association of HLH with intracellular pathogens that typically induce Th1 immune responses, such as M. tuberculosis; therefore, this suggests that dysregulation of Th1 immune responses to pathogens may also play a role in triggering HLH.3

HLH carries a high mortality rate if untreated or treatment is initiated late in the disease process; so early initiation of treatment, even while awaiting confirmation of the diagnosis, is recommended if there is high clinical suspicion.4 Reasons for delays in initiating treatment include clinicians’ unfamiliarity with the disease given its rarity, its variable clinical presentation, clinical and laboratory findings, and also the time it may take for specialised test results to come back. Furthermore, not all patients will fulfil the diagnostic criteria or may develop one of the diagnostic criteria later in the disease course.5

Current treatment of primary HLH follows the Histiocyte Society HLH-2004 treatment protocol, which can also be beneficial for patients with secondary HLH.5 However, in cases of secondary HLH, initial treatment in the form of the HLH-2004 protocol may then be adapted depending on the underlying disease.5 EBV-associated HLH is treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy as it can mimic T-cell lymphoma, but non-viral associated HLH often responds to treatment of the underlying infection.3 This is because treating the underlying infection may then remove the stimulus for activation of the immune system. An additional benefit in treating the triggering infection alone is that it may allow some patients to avoid the toxic side effects associated with the chemoimmunotherapy agents used in the HLH-2004 treatment protocol, such as severe immunosuppression. Haemopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) is a recognised curative therapy for HLH, particularly in familial HLH; however, it is associated with high treatment-related morbidity and mortality.8

Given the high mortality rate of HLH and the rapidity of its progression, particularly if untreated, patients should receive treatment before the diagnosis is confirmed if there is high clinical suspicion. Furthermore, early treatment can limit disease progression and the risk of irreversible tissue damage, and can increase chances of achieving a good response to treatment.5

M. tuberculosis is a recognised cause of HLH and a review by Brastianos et al 20069 identified at least 37 reported cases in the English language literature, with further cases of HLH associated with TB having since been reported.10 11 An important point highlighted by this review and subsequent case reports is that HLH associated with TB carries a high mortality (of approximately 50%) for patients not receiving any treatment or due to a delay in initiating treatment. Treatment with anti-TB treatment and chemoimmunotherapy or a combination of both improves outcomes.

This report describes a case of HLH associated with M. tuberculosis infection.

A negative ELISPOT and lymph node FNA suggested initial features were not related to TB. However, lymphadenopathy, fevers and splenomegaly may have reflected the disease and close contact to a patient with TB convinced initial treating physicians to include TB treatment, although this was curtailed due to toxicity. The decision that TB was not the cause of disease led to escalation of immunosuppression, which would have resulted in SCT and certain death had further extensive investigations not been performed. Whether the primary disease was TB, or whether reactivation occurred due to HLH treatment cannot be definitively determined. However, his continued response and lack of relapse of HLH following complete TB treatment leads us to suggest this may have been the primary disease.

It is notable that a negative TB ELISPOT cannot exclude a diagnosis of TB;12 therefore, it is not useful in a high probability case and is known to be affected by immunosuppressive states. Further investigation is required if there is high clinical suspicion. In particular, culture of relevant tissues or fluids is essential. Also of interest is how useful bone marrow examination can be in diagnosing TB.13 Although examination of bone marrow can be useful in rapidly diagnosing TB by demonstrating granulomata, a culture for bacteria, TB and fungi is mandatory in patients presenting with fever. Without culture, antimicrobial sensitivities cannot be determined and the diagnosis cannot be confirmed. This has particular relevance for patients from parts of the world where drug resistance is common. It is also relevant for infection control since positive microbiology from respiratory samples requires infection prevention strategies in hospital. Furthermore, TB is a statutorily notifiable disease and contact tracing must be undertaken for household contacts.

This case highlights the importance of considering TB as an infective cause of HLH and the need to have a low threshold for initiating empiric anti-TB treatment in individuals for whom there is a high clinical suspicion once the relevant clinical samples have been obtained for culture and even if confirmation of the diagnosis of TB is still pending. Delay in treatment can increase morbidity and mortality both from HLH as well as from the treatment given, particularly if chemoimmunotherapy was not necessarily required.

Learning points.

In patients presenting with fevers, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly and cytopenias, particularly in association with hyperferritinaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia, a diagnosis of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) should be considered.

If a diagnosis of HLH is suspected, investigations should be instigated not only to confirm the diagnosis, but to identify the underlying cause of HLH as this can guide treatment decisions.

Non-viral infection-associated HLH often responds to treatment of the underlying infection.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) infection is a recognised infective cause of HLH.

If TB-associated HLH is suspected, there should be a low threshold for initiating anti-TB treatment even when confirmation of the diagnosis of TB is still pending, as early treatment can reduce morbidity and mortality.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank our patient for allowing us to write up his case and for his enthusiastic support throughout the process. The patient was originally under the care of Dr Karthik Ramasamy at the Royal Berkshire Hospital where the diagnosis was made. Following the patient's transfer to the Hammersmith Hospital for further treatment, he was under the care of the haematology team comprising YMTH, TP, AL, ML and NC. Both as an inpatient and outpatient, the patient also received input from the respiratory and infectious diseases teams under Dr Onn Min Kon and Professor Shiranee Srikandan, respectively.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rouphael NG, Talati NJ, Vaughan C et al. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2007;7:814–22. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70290-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janka G, Imashuku S, Elinder G et al. Infection and malignancy-associated hemophagocytic syndromes: secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1998;12:435–44. 10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70521-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisman DN. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2000;6:601–8. 10.3201/eid0606.000608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2009:127–31. 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Histiocyte Society Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Study Group. Treatment Protocol of the Second International HLH Study 2004. http://www.uni-ulm.de/expane/docs/HLH%202004%20Study%20Protocol.pdf (accessed 19 May 2014).

- 6.Henter JL, Horne A, Aricó M et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. 10.1002/pbc.21039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filipovich A, McClain K, Grom A. Histiocytic disorders: recent insights into pathophysiology and practical guidelines. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010; 16(1 Suppl):S82–9. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larroche C, Mouthon L. Pathogenesis of hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS). Autoimmun Rev 2004;3:69–75. 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00091-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan MB, Filipovich AH. Hematopoietic cell transplantation for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single (big) step. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;42:433–7. 10.1038/bmt.2008.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brastianos PK, Swanson JW, Torbenson M et al. Tuberculosis-associated haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:447–54. 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70524-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shea YF, Chan JFW, Kwok WC et al. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an uncommon clinical presentation of tuberculosis. Hong Kong Med J 2012;18:517–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claessens YE, Pene F, Tulliez M et al. Life-threatening hemophagocytic syndrome related to mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur J Emerg Med 2005;13:172–4. 10.1097/01.mej.0000190275.85107.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rangaka MX, Wilkinson KA, Glynn JR et al. Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays for incident active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:45–55. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70210-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akpek G, Lee SM, Gagnon DR et al. Bone marrow aspiration, biopsy, and culture in the evaluation of HIV-infected patients for invasive mycobacteria and histoplasma infections. Am J Hematol 2001;67:100–6. 10.1002/ajh.1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]