Abstract

A 34-year-old nulliparous woman with a long-standing history of uterine fibroids and infertility had undergone prior open myomectomy, then uterine artery embolisation in treatment of an apparent large fibroid. Imaging on referral revealed an atypical 12×11×10 cm pelvic mass with the appearance of a fibroid. At laparotomy, the lesion was encapsulated but softer than a fibroid and located deep in the paravaginal space. The histopathological outcome was an aggressive angiomyxoma.

Background

Aggressive angiomyxoma is a rare entity, especially in the paracolpos. Aggressive angiomyxoma more commonly affects the vulva in premenopausal women.1

Case presentation

An otherwise healthy, 34-year-old nulliparous woman presented with urinary frequency and occasional stress incontinence of 1 year duration. Menstruation was normal. She was planning to conceive soon. She had undergone open myomectomy in treatment of fibroid 2 years previously, followed by uterine artery embolisation for apparent regrowth of the fibroid. On abdominal palpation, the uterus felt symmetrically enlarged to 4 cm above the pubic symphysis. On vaginal examination, this mass was felt to be consistent with a fibroid enlargement of the uterus. Ultrasound showed a 12×11×10 cm mass abutting the left side of the uterus. Consent for case reporting was obtained.

Investigations

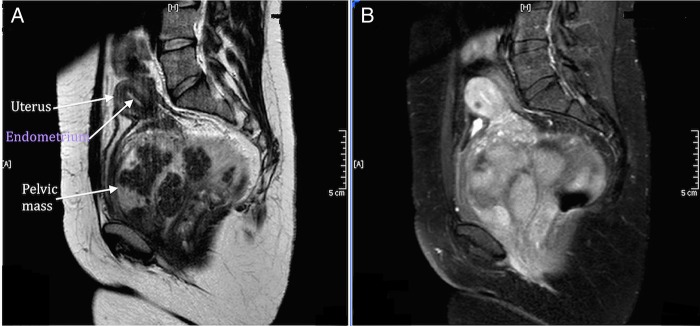

Full blood count, renal and hepatic biochemistry, inflammatory markers and tumour markers (CA 125, carcinoembryonic antigen, C 19.9, human chorionic gonadotropin, α-fetoprotein, lactate dehydrogenase, oestradiol, testosterone) were normal. Contrast MRI showed a large mass with the appearance of a pedunculated fibroid arising from the lower uterine segment and cervix on the left side, and expanding into the uterovesical pouch (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sagittal MRI (A) without contrast and (B) with contrast. Large atypically located pedunculated mass between bladder and uterus. Endometrium preserved.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis in women presenting with urinary frequency and incontinence is broad. We were guided in this case by histology of benign fibroid from prior myomectomy and considered that the extrinsic pressure on the bladder was the most likely cause of her urinary symptoms. The differential for the mass included uterine fibroid, Gartner's cyst and soft tissue neoplasms.

Treatment

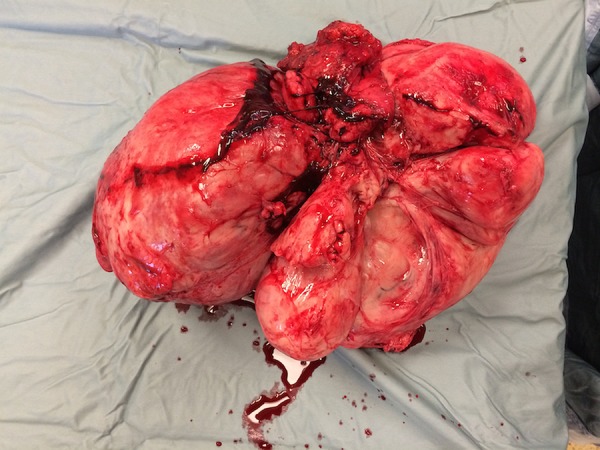

At laparotomy, the large tumour was found to be entirely subperitoneal. Peripherally circumscribed, it was wrapped around the left side of the cervix and vagina, filling the rectovaginal space posteriorly, extending laterally to obturator fossa and anteriorly into the vesicovaginal space. It appeared to take its vascular supply from the vaginal fornix. The cut appearance was of a whorled, yellow, firm lesion (figure 2). Complete excision necessitated removal of a small portion of the vaginal fornix. The patient had massive intraoperative bleeding with estimated blood loss of 2500 mL despite elective ligation of the internal iliac artery at the start of the procedure. She received 4 units of packed red cells, one unit of fresh frozen plasma and 2 g of tranexamic acid. The postoperative period was uneventful.

Figure 2.

Well-circumscribed and well-encapsulated fleshy tan gelatinous multilobulated mass.

Outcome and follow-up

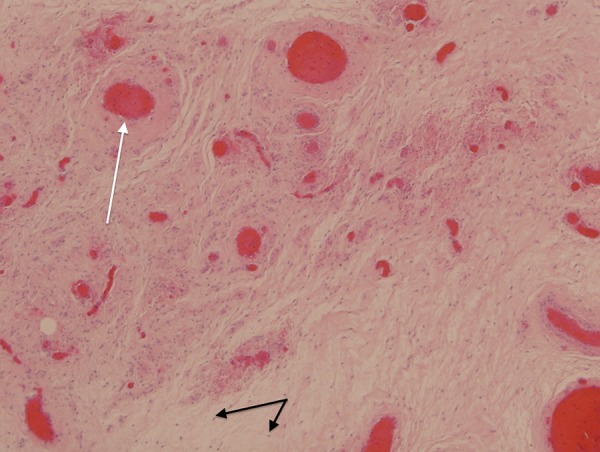

The patient made a full recovery and her urinary symptoms resolved completely. The histological outcome was an aggressive angiomyxoma (figure 3). A baseline postoperative MRI at 8 weeks showed some changes in the pelvis, suspicious of residual disease, but a further scan at 6 months was normal. In retrospect, the changes seen at 8 weeks were considered to be due to postoperative inflammatory changes. A further MRI is planned after delivery if the patient is successful in achieving pregnancy.

Figure 3.

H&E slide showing widely scattered bland spindle cells (black arrow) with no atypia, extremely rare mitoses and no atypical mitotic figures, within a myxoid background with accompanying prominent, dilated, thick vascular structures (white arrows).

Discussion

Aggressive angiomyxoma is a rare tumour; 250 cases have been reported in the literature. It is a benign but locally invasive myxoid tumour of the pelvis. The term aggressive relates to the infiltrative nature of the tumour. Local recurrence arises in 30–72% of cases despite wide local excision. There are only two reported cases of distal metastases and death. The tumour arises from the blood vessel wall, occurs most commonly in women of reproductive age and commonly affects the vulva.1 The ratio of females to males is estimated at 6:1.2 Macroscopically, the tumours are partially encapsulated and gelatinous in appearance. Histologically, angiomyxoma is a hypocellular mesenchymal tumour with occasional spindle cells.3 They express oestrogen and progesterone receptors, which supports the argument for a hormonal influence on these lesions.4 The mainstay of treatment for aggressive angiomyxoma is surgical resection. Achieving negative margins is challenging because these tumours lack a true capsule. Hormonal treatments have been attempted with some success although data remain limited. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues may reduce the tumour bulk and can be considered for neoadjuvant cytoreduction.5 Tamoxifen and chemotherapeutic agents have not been successful. Radiotherapy does not have a role in adjuvant therapy due to the low mitotic rate.6 Arterial embolisation has been tried in a number of cases with varying results.2 In this case the previous uterine artery embolisation resulted in some shrinkage. The presence of oestrogen receptors raises the possibility of pregnancy promoting growth as the placenta produces oestriol. The effect of pregnancy on the risk of relapse is unknown.

Learning points.

Although most common in the vulva, aggressive angiomyxomas can arise from the soft tissues above the pelvic floor.

Large tumours can affect other pelvic organs leading to urinary symptoms, and can impact on fertility.

Complete excision is considered the best therapeutic option. The effect of the high oestrogen state in pregnancy on the risk of relapse is unknown.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Lefkowitz M et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a clinicopathologic study of 29 female patients. Cancer 1996;78:79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han-Geurts IJ, van Geel AN, van Doorn L et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma: multimodality treatments can avoid mutilating surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 2006;32:1217–21. 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steeper TA, Rosai J. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum: report of nine cases of a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol 1983;7:463–75. 10.1097/00000478-198307000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagga R, Keepanasseril A, Suri V et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva in pregnancy: a case report and review of management options. MedGenMed 2007;9:16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz PE, Hul P, McCarthy S. Hormonal therapy for aggressive angiomyxoma: a case report and proposed management algorithm. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2014;18:55–61. 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182a22019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan YM, Hon E, Ngai SW et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma in females: is radical resection the only option? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2000;79:216–20. 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079003216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]