Abstract

This is a rare case of penile and generalised calciphylaxis. We describe the case of a patient admitted to our hospital for septic shock and necrotic skin findings, end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis. Skin findings turned out to be calciphyactic lesions. The patient was taken to the operating room for penile debridement and started on antibiotics. He was treated with sodium thiosulfate and switched to haemodialysis. Calciphylaxis is a rare disease in which the treatment is basically supportive. Further studies are needed to identify the risk factors, mechanisms of disease and treatment modalities.

Background

This case is about a very rare disease that has been described in the literature. What makes our case unique is that it involves the penis and was seen in a patient on peritoneal dialysis. Treatment is supportive. Sodium thiosulfate is the mainstay of treatment in haemodialysis. This patient was taken to the operating room for penile debridement, then converted to haemodialysis and started on sodium thiosulfate. We describe a rare disease, unique presentation and unique treatment modalities.

Case presentation

Introduction

Calciphylaxis (or calcific uraemic arteriolopathy) is a life-threatening condition that affects 1–4% of patients with end-stage renal disease on haemodialysis1 or those who received renal transplant.2 3 It is characterised by medial calcification and intimal fibrosis of medium and small arteries. Macroscopically, cutaneous necrosis is a characteristic clinical presentation that affects the distal extremities, buttocks, thighs and, less frequently, the penis. It is a clinical condition with a high mortality rate >60% within 6 months.4

Risk factors include female sex, obesity, high phosphate concentration, medications (warfarin,5 systemic steroids, calcium binders, vitamin D analogues), a hypercoagulable state and hypoalbuminaemia.4 Warfarin is most frequently associated with the disease.

Diagnosis is clinical: painful, non-ulcerating subcutaneous nodules or plaques, non-healing ulcers and/or necrosis, which are most commonly present in the thigh and areas of increased adiposity.

Treatment consists of dialysis, sodium thiosulfate, wound care, correction of calcium–phosphate abnormalities, cinacalcet, parathyroidectomy (if the parathyroid hormone (PTH) is elevated) and supportive care.

We describe a rare clinical case of penile and generalised calciphylaxis in a patient on peritoneal dialysis.

Case report

A 54-year-old Caucasian man was admitted to our hospital for septic shock of unknown origin.

The patient had a medical history of heart disease (coronary artery disease, coronary artery bypass grafting, mechanical aortic valve, congestive heart failure with preserved ejection fraction of 55%), type 2 diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation on warfarin.

He initially presented to an outside hospital with altered mental status, hypotension and hypoxia. He was diagnosed with septic shock of unknown aetiology: pulmonary versus urinary versus soft tissue infection. He was started on broad spectrum antibiotics and transferred to our hospital.

On admission to the intensive care unit, the patient was noted to be hypotensive with altered mental status. His laboratory examination showed an elevated international normalised ratio (10), elevated creatinine (4.72 mg/dL), bicarbonates of 18 mmol/L, elevated lactates (8 mmol/L) and leucocytosis (71 000–65% bands). No other significant electrolyte abnormalities were noted.

On physical examination, he had extensive necrotic gangrenous lesions on the legs, buttocks, thighs, lower back and glans of the penis (figures 1–5).

Figure 1.

Leg lesions.

Figure 2.

Thighs, hamstrings and leg lesions.

Figure 3.

Penile and scrotal necrosis/gangrene.

Figure 4.

Leg lesions.

Figure 5.

Inner thigh necrotic lesions.

The lesions were extremely painful, requiring high opioid doses for pain control.

On review of medical history, the onset of skin lesions was 4 months prior to admission. The patient underwent a skin biopsy in a suburban dermatology clinic which showed non-specific histological changes compatible with skin necrosis.

He was diagnosed with calciphylaxis based on a clinical presentation combined with a medical history of diabetes, end-stage renal disease and warfarin use.

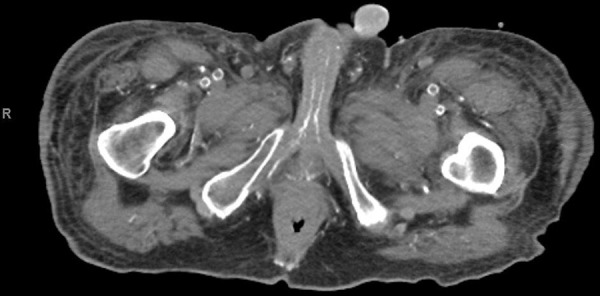

Further evaluation showed a slightly elevated PTH (94 pg/mL), as well as extensive abdominal, pelvic and penile arterial calcifications on a non-contrast CT scan (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pelvic and penile artery calcifications.

Treatment

The patient did not require vasopressors and remained haemodynamically stable throughout his stay as an inpatient. Peritoneal dialysis was discontinued on presentation. He was immediately started on haemodialysis via a temporary right intrajugular dialysis catheter, three times a week, with addition of sodium thiosulfate 25 g at the end of each dialysis session.

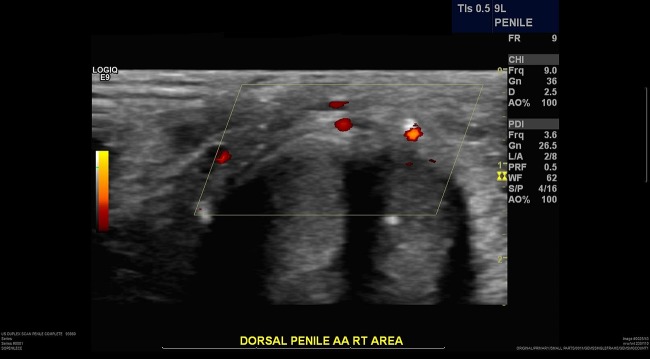

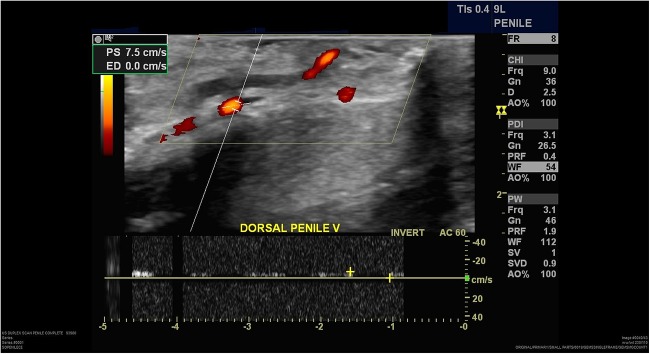

Penile involvement required more advanced therapy. The patient suffered from urine retention caused by glans and penile tip lesions requiring a Foley catheter, which was introduced with much difficulty. Penile ultrasound showed absent arterial and venous flow within the corpora cavernosa, absent arterial flow within the dorsal penile artery, and advanced calcifications of all penile arteries (figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7.

Absent arterial flow in dorsal penile arteries.

Figure 8.

Decreased/absent blood flow in dorsal penile veins.

With haemodialysis and sodium thiosulfate, the patient symptomatically improved and the pain decreased.

Penile lesions were treated surgically: the patient was taken to the operating room for debridement 2 weeks after admission. Intraoperative cystoscopy could not be advanced because of extensive necrosis. The glans was subsequently debrided down to the level of the subcoronal area. The necrotic glans tissue was excised sharply down to the level of the urethra and then removed. A fine cut was made until the urethra was viable. The urethra had been black and somewhat dusky. Cystoscopy was then performed; cystoscope passed through urethral canal, therefore patency verified. The remainder of the corpora cavernosa was then sutured and closed, and the urethra also sutured onto it.

The remainder of the patient's hospital stay was unremarkable. His pain improved, but skin lesions were stable, did not completely heal nor progress. Generalised surgical debridement was not performed because of the extension of the lesions.

Outcome and follow-up

After pain control and recovery from sepsis, the patient was discharged home.

He was then readmitted 1 week after discharge for urosepsis versus peripherally inserted central catheters line-related sepsis. He was treated in the intensive care unit with vasopressors and antibiotics but unfortunately expired after 1 week of intensive supportive care.

Discussion

Our patient has end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis. Calciphylaxis is rarely described in patients on peritoneal dialysis.6 It is a disease mostly noted in patients on haemodialysis.1 Few limited studies have shown that peritoneal dialysis is by itself a risk factor, but this remains to be proven.7

Our patient had two additional risk factors: he was on warfarin for mechanical aortic valve and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, in addition to type 2 diabetes. Warfarin is one of the most frequently associated risk factors.5 Calciphylaxis lesions are frequently confused with warfarin-induced skin necrosis.

Diagnosis is clinical. Our patient's presentation is typical for generalised calciphylaxis, in addition to rarely described penile lesions.

Warfarin was discontinued and the patient was switched to enoxaparin. Warfarin promotes vascular calcification via inhibiting matrix GLA metalloproteinases.6 Discontinuing warfarin and reversing its effect by vitamin K administration has become a common practice despite the absence of clinical evidence. Bridging to low-molecular-weight heparin was necessary because the patient had a mechanical aortic valve and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; therefore, continuous anticoagulation was mandatory.

The mainstay of treatment was converting the patient to haemodialysis and starting treatment with sodium thiosulfate. No randomised controlled trials studied the efficacy of sodium thiosulfate.8 In a retrospective study of 53 patients on haemodialysis, 73% improved or resolved with sodium thiosulfate administration.

There is no standard dose of sodium thiosulfate. We used the most commonly reported dose: 25 g during haemodialysis sessions. Some practices are infusing sodium thiosulfate inside the peritoneum. We converted the patient to haemodialysis and used sodium thiosulfate within dialysis sessions.

The largest study to date evaluating sodium thiosulfate therapy is an Austrian retrospective study in 2013 which analysed 27 patients with calciphylaxis treated with sodium thiosulfate in seven dialysis centres. Data showed a 52% complete remission rate. Remission depended on early diagnosis, early initiation of treatment, fewer patients’ comorbidities and less severe disease on presentation.9

The mechanism of action of sodium thiosulfate is unknown. The leading hypothesis includes chelation of calcium ions, dissolution of insoluble calcium deposits and restoration of endothelium.10 11

Other supportive treatment includes pain control with opioids, local wound care and maintaining adequate nutrition, because ulcerated lesions and pain tend to decrease appetite via cytokine release.

Regarding penile involvement, ultrasound scan showed complete calcification with absent flow to the glans. Penile involvement was managed surgically. Our patient had a partial penectomy and debridement.12 A total of 52 cases of penile calciphylaxis are described in the literature.13–15 It is a rare localisation of calciphylaxis lesions. Treatment usually consists of a combined medical16 and surgical approach.

Learning points.

Calciphylaxis is rare in patients with peritoneal dialysis.

Treatment is somehow similar to patients on haemodialysis. One option is to convert patients to haemodialysis and administer sodium thiosulfate with dialysis.

Further studies are also needed to identify risk factors, mechanisms and other treatment options for calciphylaxis. The main barrier is the low incidence of disease and high morbidity/mortality rates.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sandhu G, Casares P, Ranade A et al. . Acute calciphylaxis precipitated by the initiation of hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol 2013;80:301–5. 10.5414/CN107524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adrogué HJ, Frazier MR, Zeluff B et al. . Systemic calciphylaxis revisited. Am J Nephrol 1981;1:177–83. 10.1159/000166536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janigan DT, Hirsch DJ, Klassen GA et al. . Calcified subcutaneous arterioles with infarcts of the subcutis and skin (“calciphylaxis”) in chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;35:588–97. 10.1016/S0272-6386(00)70003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazhar AR, Johnson RJ, Gillen D et al. . Risk factors and mortality associated with calciphylaxis in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 2001;60:324–32. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00803.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coates T, Kirkland GS, Dymock RB et al. . Cutaneous necrosis from calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;32:384–91. 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9740153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.New N, Mohandas J, John GT et al. . Calcific uremic arteriolopathy in peritoneal dialysis populations. Int J Nephrol 2011;2011:982854 10.4061/2011/982854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH et al. . Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:1139–43. 10.2215/CJN.00530108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nigwekar SU, Brunelli SM, Meade D et al. . Sodium thiosulfate therapy for calcific uremic arteriolopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:1162–70. 10.2215/CJN.09880912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zitt E, König M, Vychytil A et al. . Use of sodium thiosulphate in a multi-interventional setting for the treatment of calciphylaxis in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:1232–40. 10.1093/ndt/gfs548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yatzidis H. Successful sodium thiosulphate treatment for recurrent calcium urolithiasis. Clin Nephrol 1985;23:63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayden MR, Tyagi SC, Kolb L et al. . Vascular ossification-calcification in metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and calciphylaxis-calcific uremic arteriolopathy: the emerging role of sodium thiosulfate. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2005;4:4 10.1186/1475-2840-4-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akai A, Okamoto H, Shigematsu K et al. . Revascularization surgery for penile calciphylaxis. J Vasc Surg 2013;58(6):1665–7. 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Neil B, Southwick AW. Three cases of penile calciphylaxis: diagnosis, treatment strategies, and the role of sodium thiosulfate. Urology 2012;80:5–8. 10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatty TA, Riaz K. Calciphylaxis mimicking penile gangrene: a case report. ScientificWorldJournal 2009;9:1355–9. 10.1100/tsw.2009.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García Morúa A, Gutiérrez García JD, Arrambide Gutiérrez JG et al. . Penile calciphylaxis: 5-year experience and literature review. Actas Urol Esp 2009;33:1019–23. (Urology Service, Hospital Universitario Dr. José E. González, Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico). 10.4321/S0210-48062009000700015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandhu G, Gini MB, Ranade A et al. . Penile calciphylaxis: a life-threatening condition successfully treated with sodium thiosulfate. Am J Ther 2012;19:e66–8. 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181e3b0f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]