Summary

Platelets are specialized hemostatic cells that circulate in the blood as anucleate cytoplasts. We report that platelets unexpectedly possess a functional spliceosome, a complex that processes pre-mRNAs in the nuclei of other cell types. Spliceosome components are present in the cytoplasm of human megakaryocytes and in proplatelets that extend from megakaryocytes. Primary human platelets also contain essential spliceosome factors including small nuclear RNAs, splicing proteins, and endogenous pre-mRNAs. In response to integrin engagement and surface receptor activation, platelets precisely excise introns from interleukin-1β pre-mRNA, yielding a mature message that is translated into protein. Signal-dependent splicing is a novel function of platelets that demonstrates remarkable specialization in the regulatory repertoire of this anucleate cell. While this mechanism may be unique to platelets, it also suggests previously unrecognized diversity regarding the functional roles of the spliceosome in eukaryotic cells.

Introduction

Gene expression in nucleated cells is regulated at several checkpoints. A critical step is the removal of non-coding introns from newly transcribed pre-mRNAs, a process that occurs cotranscriptionally in the nucleus by a trans-acting complex termed the spliceosome (Maniatis and Reed, 2002). The human spliceosome contains small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) and auxiliary proteins that impart the correct architecture necessary for proper intron recognition and excision (Maniatis and Reed, 1987). Splicing ensures that mature, translatable mRNAs are available for export to the cytoplasm. Observations to date indicate that the spliceosome operates within nuclear boundaries (Maniatis and Reed, 2002); a functional role for this complex in extranuclear domains has not been described.

Megakaryocytes and their progeny, circulating anucleate platelets, are highly specialized mammalian cells that participate in hemostatic and inflammatory functions (Weyrich et al., 2003). Presumably, the spliceosome is critically active in megakaryocytes where regulated mRNA expression, together with a host of other processes, is required to produce functional platelets. Megakaryocyte differentiation occurs in the bone marrow and involves two distinct stages. Commitment of the hematopoietic progenitor cell to the first stage is characterized by an arrest of proliferation and initiation of endomitosis, a process involving several cycles of genome replication without cell division that results in diploid chromosome numbers that range from 16N to 128N (Ravid et al., 2002). The second stage of maturation is associated with rapid cytoplasmic expansion and robust transcription that drives the expression of genes essential for megakaryocyte maturation, organelle and granular formation, and the development of specialized proplatelet extensions that eventually spawn individual platelets that circulate in the blood (Hartwig and Italiano, 2003). Although transcriptional processes are regnant during megakaryocyte differentiation, the spliceosome and splicing events have not been characterized during megakaryopoiesis or thrombopoiesis.

Here we explored intracellular distribution patterns in a model of human megakaryocyte differentiation and proplatelet formation and found that critical spliceosomal components are present in the cytoplasm of these cells. Parallel analysis of primary human platelets demonstrated that the net result is the accumulation of essential spliceosomal proteins and small nuclear ribonucleic acids (snRNAs) in these anucleate cytoplasts. In addition, mature human platelets isolated from peripheral blood retain a subset of pre-mRNAs, and we characterized one of these, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and found that it is spliced into mature message in response to cellular activation. This splicing event coincides with new synthesis of IL-1β protein and was recapitulated in an ex vivo splicing system. These unexpected results indicate that functional spliceosomal components are distributed to platelets during thrombopoiesis and that splicing can proceed in response to outside-in signals in an environment that is devoid of direct nuclear regulation and transcription.

Results

Megakaryocytes, Proplatelets, and Mature Platelets Contain Critical Splicing Factors

Although mature platelets are anucleate, we discovered that they retain and splice endogenous pre-mRNAs (see below). Therefore, we hypothesized that critical spliceosome components accumulate in proplatelets during thrombopoiesis, the formation of blood platelets, and are subsequently maintained in circulating platelets after their release from the bone marrow. To explore this possibility, we first developed a model of human proplatelet formation that mimics the in vivo process. Megakaryocytes develop from marrow pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells, and megakaryopoiesis involves regulated cytoplasmic expansion and biogenesis of organelles, granules, and requisite platelet constituents (Italiano and Shivdasani, 2003). In murine systems, the megakaryocyte cytoplasm eventually undergoes a massive reorganization into beaded extensions that are referred to as proplatelet chains, transforming the megakaryocyte into a residual nucleus surrounded by proplatelet processes (Italiano et al., 1999). Megakaryocyte maturation ends when proplatelets are separated from the cell body. The subsequent dissolution of cytoplasmic bridges that connect pro-platelets releases individual platelets into the circulation (Hartwig and Italiano, 2003).

Using hematopoietic CD34+ progenitor cells, we developed a human model of megakaryocyte differentiation and proplatelet formation (Figure 1 and M.M.D., N.D.T., C.C.Y., F.J.R., T.M.M., K.H.A., G.A.Z., and A.S.W., unpublished data). Mature megakaryocytes generated in this fashion contain one to three nuclei, approximate the size of marrow megakaryocytes, and are packed with granules, organelles, and ribosomes (Figures 1A and 1B). Granules in the CD34+-derived megakaryocyte cytoplasm and megakaryocyte proplatelet extensions stain positively for P-selectin (data not shown), a key constituent of platelet α granules that translocates to the surface membrane during cellular activation (McEver, 1990). CD34+-derived megakaryocytes also contain a rich microtubular network (data not shown) that is critical for the cytoskeletal mechanics of platelet biogenesis (Italiano et al., 1999). In addition, megakaryocytes and megakaryocytes with proplatelet extensions stain positively for αIIb and β3 integrin subunits (Figure 2 and data not shown), which heterodimerize to form αIIbβ3 integrin, a unique biomarker for cells of this lineage (Hato et al., 2002).

Figure 1. U1 70K Protein Is Localized in the Cytoplasm of Megakaryocytes and in Pro-platelets that Extend from Megakaryocytes.

(A) Scanning electron micrographs of a CD34+ stem-cell-derived megakaryocyte (left panel) and a megakaryocyte with proplatelet extensions (right panel). The white arrows in the right panel point to proplatelets, while the blue arrow indicates the cell body.

(B) Transmission electron micrographs of a megakaryocyte (top left panel) and a megakaryocyte with a proplatelet extension (top right panel). The arrow in the top panel is pointing to the proplatelet extension. The bottom left panel is a corresponding photomicrograph of the megakaryocyte taken at a higher magnification to identify the nuclear membrane. The bottom middle and right panels are corresponding photomicrographs of the megakaryocyte with a proplatelet extension taken at higher magnifications to identify the nuclear membrane. The black arrows in the bottom panels identify the nuclear envelope.

(C) A representative megakaryocyte and a megakaryocyte with proplatelet extensions were costained with an anti-U1 70K antibody (green) and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; red), a fluorescent lectin that binds cell membranes and granules. In the megakaryocyte, U1 70K protein is detected in the cytoplasm (white arrow in the top, right panel) as well as in the nucleus. U1 70K protein is also observed in proplatelet extensions of the megakaryocyte (white arrows in the bottom, right panel). The right panels are merged images of WGA and U1 70K protein. The blue arrow in the bottom panel indicates U1 70K staining in the nucleus. The photomicrographs in this figure are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 2. Critical Spliceosome Factors Are Present in the Cytoplasm of Megakaryocytes, in Megakaryocytes with Proplatelet Extensions, and in Circulating Platelets.

(A and B) Megakaryocytes were stained with an anti-U2AF65 (A) or anti-SF2/ASF (B) and an antibody against the integrin αIIb subunit. Low-magnification photomicrographs for each factor are shown in grayscale. The merged photomicrographs in the right panels are higher magnifications of the areas outlined in blue in the middle panels. In the right panels, U2AF65 and SF2/ASF immuno-localization is shown in green, and αIIb immunostaining is in red. The white arrows in the top panels indicate cytoplasmic staining and in the bottom panels identify immunostaining in proplatelet extensions.

(C) Platelets were left in suspension (quiescent) or allowed to adhere and spread on immobilized fibrinogen in the presence of thrombin for 30 or 60 min. The platelets were stained with antibodies against U2AF65 (top panels) or SF2/ASF (bottom panels) and the αIIb integrin subunit (U2AF65 and SF2/ASF immunolocalization, green; αIIb immunostaining, red). Controls for antibody specificity were performed (see Figure 3C for examples). Cellular spreading on immobilized fibrinogen in the presence of thrombin demonstrates that the platelets were efficiently stimulated. U2AF65 and SF2/ASF were also detected in platelets by Western blotting (data not shown). The images in this figure are representative of three independent studies.

Inspection of staining patterns in adherent megakaryocytes, megakaryocytes with proplatelet extensions, and mature platelets indicate that each cell stage contains components of the spliceosome (Figures 1C and 2). This was unexpected because platelets are cytoplasts and are generally thought to be devoid of nuclear constituents. We initially examined U1 70K protein, a component of the U1 snRNP (Ruby and Abelson, 1988). U1 70K is essential for incorporation of the U1 snRNP and SF2/ASF into a complex with pre-mRNAs that is required for pre-mRNA processing (Kohtz et al., 1994). U1 70K protein has at least one defined nuclear localization signal and is rapidly transported to the nucleus when it is overexpressed in cell lines (Romac et al., 1994). Endogenous U1 70K protein is also confined to the nucleus in HeLa cells (data not shown), the principal cell line used to characterize the human spliceosome (Zhou et al., 2002a). U1 70K protein is present in the nucleus as well as the cytoplasm of megakaryocytes and in proplatelets that extend from megakaryocytes (Figure 1C).

In addition to U1 snRNP binding at the 5′ splice site, spliceosome assembly involves interactions between the U2 snRNP auxiliary factor (U2AF) and pyrimidine tracts at the 3′ splice site of the target pre-mRNA (Graveley et al., 2001). U2AF is a heterodimer that contains 65 and 35 kDa subunits (Graveley et al., 2001). We found U2AF65 in the nucleus and cytoplasm of megakaryocytes (Figure 2A, top panels). U2AF65 protein is also present in proplatelet extensions (Figure 2A, lower panels) and in mature, human platelets (Figure 2C, top panels). We also found that megakaryocytes and proplatelets contain serine-arginine-rich (SR) family members, proteins that stabilize U1 SnRNP and U2AF binding at the 5′ and 3′ splice sites, respectively (Wu and Maniatis, 1993). Splicing requires the presence of at least one member of the SR family (Black, 2003), and HeLa cell S100 extracts do not splice pre-mRNAs due to limiting amounts of SR proteins (Mayeda and Krainer, 1999). The SR family includes members such as SRp20, SRp30c, 9G8, SRp40, SRp55, SRp70, SF2/ASF, and SC35 (Black, 2003). We focused on SF2/ASF, a prototypic SR protein that regulates constitutive splicing as well as some alternative splicing events (Hastings and Krainer, 2001). We found SF2/ASF in the cytoplasm of megakaryocytes and in proplatelets that extend from megakaryocytes as well as in mature, circulating platelets (Figure 2B and 2C).

In further analyses, we also detected additional spliceosomal factors in these cells. The SR-related protein SRm160 that coactivates pre-mRNA splicing (Blencowe et al., 1998) is present in quiescent and activated platelets (Figure S1). Survival motor neuron (SMN), which recycles pre-mRNA splicing factors and is required for pre-mRNA splicing (Pellizzoni et al., 2002), is also found in megakaryocytes, proplatelet extensions of megakaryocytes, and mature platelets (Figure S2). SMN is also important for the biogenesis of snRNPs because it brings together Sm proteins with U snRNAs (Yong et al., 2002). In this regard, SmBB′ and SmD1 are localized in the cytoplasm of megakaryocytes, pro-platelets that extend from megakaryocytes, and mature platelets (Figure S3).

In addition to relying on splicing proteins, assembly of the spliceosome on pre-mRNA requires base pairing of U snRNAs with specific domains of the pre-mRNA (Hastings and Krainer, 2001). There are five U snRNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6), each of which is required for efficient splicing (Hastings and Krainer, 2001). U snRNAs have a unique 5′ terminal cap structure containing the nucleoside 2,2,7-trimethylguanosine (TMG) (Krainer, 1988; Will and Luhrmann, 2001). Using an antibody that is specific for the TMG cap, we detected U snRNAs in the nucleus and cytoplasm of megakaryocytes and in proplatelets that extend from megakaryocytes (Figure 3A). Consistent with this finding, Northern analysis using RNA from mature human platelets revealed each of the U snRNAs, and immunostaining confirmed that primary circulating platelets contain U snRNAs (Figures 3B and 3C).

Figure 3. Localization of U snRNAs in Megakaryocytes, Megakaryocytes with Proplatelet Extensions, and Circulating Platelets.

(A) Localization of U snRNAs in a megakaryocyte (left panel) and a megakaryocyte with a proplatelet extension (right panel) was characterized with an anti-TMG antibody. Staining of U snRNAs and the αIIb integrin subunit are shown in green and red, respectively (blue arrows, nuclear localization of U snRNAs; white arrows, cytoplasmic localization of U snRNAs).

(B) Northern analysis of U snRNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) in HeLa cells and circulating platelets (Plt). The two panels on the right are Northern blots conducted in the presence of competing unlabeled oligonucleotides demonstrating the specificity of the U snRNA probes.

(C) The top panels are control studies of circulating platelets (left and middle panels) and HeLa cells (right panel), respectively. In the platelet controls, the cells were incubated with nonimmune mouse IgG and a specific antibody against the αIIb integrin subunit (red stain). The HeLa cells (top right panel) were costained with anti-TMG (green stain) and phalloidin (red stain), a marker specific for polymerized actin. In the bottom panels, an anti-TMG antibody (green) was used to localize U snRNAs in quiescent platelets (bottom left panel) and platelets adherent to immobilized fibrinogen in the presence of thrombin for 30 (bottom middle panel) or 60 (bottom right panel) min. Staining for αIIb is in red. Each panel in this figure is representative of three independent experiments.

Pre-mRNAs Are Found in Proplatelet Extensions of Megakaryocytes and in Circulating Platelets

In mature circulating platelets, translation of specific mRNAs including the cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is repressed until the cells are appropriately stimulated (Lindemann et al., 2001a). Although the pathways that govern translation of IL-1β mRNA are incompletely defined, there is evidence that IL-1β gene expression is regulated at the level of pre-mRNA processing (Jarrous and Kaempfer, 1994) and at translational control sites (Lindemann et al., 2001a). In studies of IL-1β pre-mRNA processing, ribonuclease protection assays demonstrated that intron one in the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) is a primary area of regulation (Jarrous and Kaempfer, 1994). Because IL-1β is a regulated product of activated human platelets (Lindemann et al., 2001a), we sequenced the 5′-UTR of the IL-1β transcript in circulating platelets and found that the dominant product contains introns one and two, whereas the 3′-UTR product is a consensus sequence (Figure S4, top panel). In contrast, we only amplified exonic sequences in the 5′ and 3′ regions of the transcript for αIIb, an mRNA unique to megakaryocytes and platelets (Figure S4, bottom panel).

Because our RACE data demonstrated that mature platelets contain IL-1β pre-mRNA, we asked if IL-1β pre-mRNA is localized to the cytoplasm of megakaryocytes that are beginning to extend proplatelets. We found amplified intronic IL-1β cDNA in the cytoplasm of these platelet precursors employing probes that detect introns 1, 4, and 6 (Figure 4A, top panels). We also found pre-mRNA for IL-1β in quiescent platelets (Figure 4B, top left panel) and mature mRNA for IL-1β in platelets activated by adhesion to fibrinogen in the presence of thrombin (Figure 4B, top middle and right panels). No signal was seen when reverse transcriptase was eliminated from the RT reactions, establishing specificity of each assay (Figures 4A and 4B, bottom panels).

Figure 4. IL-1β Pre-mRNA Is Present in Developing Proplatelets as well as Quiescent Platelets, and Mature IL-1β mRNA Is Present in Activated Platelets.

(A) In situ PCR for intronic IL-1β mRNA was conducted as described in detail in the Experimental Procedures. The top panels illustrate assays using probes for introns 1, 4, and 6 and demonstrate that IL-1β pre-mRNA is present in the cytoplasm of CD34+-derived megakaryocytes that are in the process of extending proplatelets. The black arrows identify cytoplasm of the megakaryocytes. The bottom panels illustrate corresponding negative controls in which reverse transcriptase was eliminated from the RT reaction (No RT). Here, the black arrows point to unstained megakaryocytes.

(B) In situ PCR for IL-1β pre-mRNA and mature mRNA was conducted in quiescent platelets (top left panel) and in platelets adherent to fibrinogen in the presence of thrombin for 1 hr (top middle and right panels), respectively. The far right photomicrographs of adherent, activated platelets are taken at a higher magnification. In the bottom panels (No RT), the reverse transcriptase was omitted during the RT reaction. This figure represents inspection of multiple fields from three independent experiments.

Activated Platelets Splice Constitutive Pre-mRNAs

The presence of intronic sequences in the mRNA from resting platelets, which contain little or no IL-1β protein (Lindemann et al., 2001a), implied that activated platelets may use their splicing machinery to process IL-1β pre-mRNA into a translatable, intronless message. To test this postulate, we designed primers that flanked intron one of the IL-1β message and performed RT-PCR using RNA isolated from highly purified platelet preparations depleted of CD45-positive cells to ensure removal of any residual leukocytes (see Figure S5). As an additional measure, we treated the purified platelets with actinomycin D, a reagent that blocks transcription of pre-mRNAs (Lindemann et al., 2004). We found that the dominant IL-1β RNA product in quiescent platelets contains intron one (Figure 5A, top panel). We also detected trace amounts of spliced message in quiescent platelets, a finding that varied among experiments and may be due to a low level of ex vivo cellular activation (H.S., G.A.Z., A.S.W., N.D.T., unpublished data). In contrast, in stimulated platelets, IL-1β pre-mRNA is decreased and the intronless message is correspondingly increased in a time-dependent fashion (Figure 5A, top panel), consistent with in situ detection of mature IL-1β mRNA in activated, adherent platelets (see Figure 4B, top middle and right panels). TA cloning and sequencing revealed that this processed mRNA is mature, IL-1β mRNA (data not shown). The CD45+ leukocytes extracted from this platelet preparation contained mature transcripts for CXCL8 (interleukin-8), a leukocyte-specific gene product (Lindemann et al., 2004), whereas CXCL8 was absent in CD45-depleted platelet preparations (Figure 5A, bottom panel). In addition, pre-mRNA for IL-1β was not detected in monocytes stimulated with lipopolysaccharide, providing further evidence that IL-1β pre-mRNA is platelet derived (Figure S6). CD45 depletion, actinomycin D pretreatment, and the absence of CXCL8 message in platelet RNA preparations argue against genomic contamination. Nevertheless, to ensure that we did not amplify genomic DNA, we treated platelet RNA with RNase, a regimen that eliminated IL-1β pre-mRNA and mature mRNA (Figure 5B). In contrast, DNase treatment did not alter IL-1β message levels in platelets but completely degraded a genomic DNA substrate (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Activated Platelets Splice Endogenous IL-1β Pre-mRNA into Mature Message and Translate the mRNA into Protein.

(A) mRNA levels in platelets that were left quiescent (lane 1) or adhered to fibrinogen in the presence of thrombin (lanes 2–4). Lane 5 identifies mRNA levels in the CD45+ fraction extracted from this platelet preparation. On the right-hand side, the boxes represent exon 1 and 2 of the IL-1β message, which flank intron 1 (solid line).

(B) In the left panel, mRNA from platelets that were left quiescent (0) or activated by fibrinogen and thrombin for 30 min was left unmanipulated (control) or treated with RNase or DNase. The right panel depicts genomic DNA treated with DNase and RNase.

(C) Analysis of IL-1β pre-mRNA and mature mRNA in quiescent platelets and in platelets activated by adherence to fibrinogen for 2 hr in the presence of thrombin. The IL-1β gene is depicted in the top portion of this figure where exon flanking primer sets are color coded to indicate the approximate location of individual PCR reactions that span each intron of the IL-1β gene. On the right side, the boxes represent undesignated exons flanking a representative intron to illustrate the patterns of PCR products.

(D) Polymerized actin (red) and IL-1β protein (green) were stained in quiescent platelets and in platelets 8 hr after they adhered to fibrinogen in the presence of thrombin (Activated). IL-1β protein was detected in adherent platelets consistent with de novo synthesis of the protein by platelets that are activated by fibrinogen and thrombin (Lindemann et al., 2001a).

Next, we characterized full-length IL-1β mRNA in platelets to confirm that cellular activation generates a translatable message. We amplified the message under resting and activated conditions using primers that span each intron separately since platelet-derived IL-1β mRNA is in low abundance, a feature of eukaryotic mRNAs under regulatory control (Kochetov et al., 1998; Weyrich et al., 2004). We found that the pre-mRNA in unstimulated platelets contained all six introns, although introns 4–6 are partially spliced (Figure 5C, left panel). Following cellular activation, only trace amounts of pre-mRNAs remain, whereas the spliced products are present (Figure 5C, right panel). Consistent with the generation of mature message, we found that IL-1β protein accumulates in activated platelets (Figure 5D, right panel). In contrast, quiescent platelets do not contain IL-1β protein (Figure 5D, left panel). IL-1β protein accumulation also parallels regulated translation of the mRNA by platelets embedded in fibrin-rich clots where IL-1β protein is synthesized in sufficient quantities to activate human endothelial cells (Lindemann et al., 2001a). This establishes physiologic relevance for signal-dependent processing of IL-1β pre-mRNA and translation of mature IL-1β mRNA.

Platelet Extracts Splice In Vitro-Transcribed Pre-mRNA

The human spliceosome has been extensively characterized in vitro using nuclear extracts from HeLa cells (Zhou et al., 2002a; Zhou et al., 2002b). Many other cell lines fail to yield active nuclear preparations, and in vitro splicing assays have not been developed in primary human cells (Mayeda and Krainer, 1999). In our initial attempts, we found that crude platelet extracts did not splice exogenous IL-1β pre-mRNA (Figure 6C, first lane). In addition, whole-cell extracts from platelets blocked splicing by HeLa cell nuclear extracts, suggesting that unstimulated platelets have an endogenous inhibitor (or inhibitors) that silences splicing in quiescent cells (data not shown). Since intracellular localization patterns for U1 70K protein (Figure 6A) and other splicing factors (Figures 2C and 3C) change in response to activation, we postulated that the platelet spliceosome may be partitioned to specific regions within the cell. Therefore, we fractionated platelet extracts on stepped sucrose gradients to begin purifying the spliceosome. We found that U1 70K protein is predominantly found in fractions two through four (Figure 6B) and that fraction four generates a definitive intronless IL-1β message from the intron-containing precursor (Figure 6C). TA cloning and sequencing confirmed that the spliced product was indeed intronless IL-1β mRNA, and side-by-side comparisons demonstrated that it was not amplified from endogenous IL-1β mRNA present in fraction four of the platelet lysate (data not shown). The isolation of splicing-competent extracts from platelets confirms that this anucleate cell possesses a functional spliceosome.

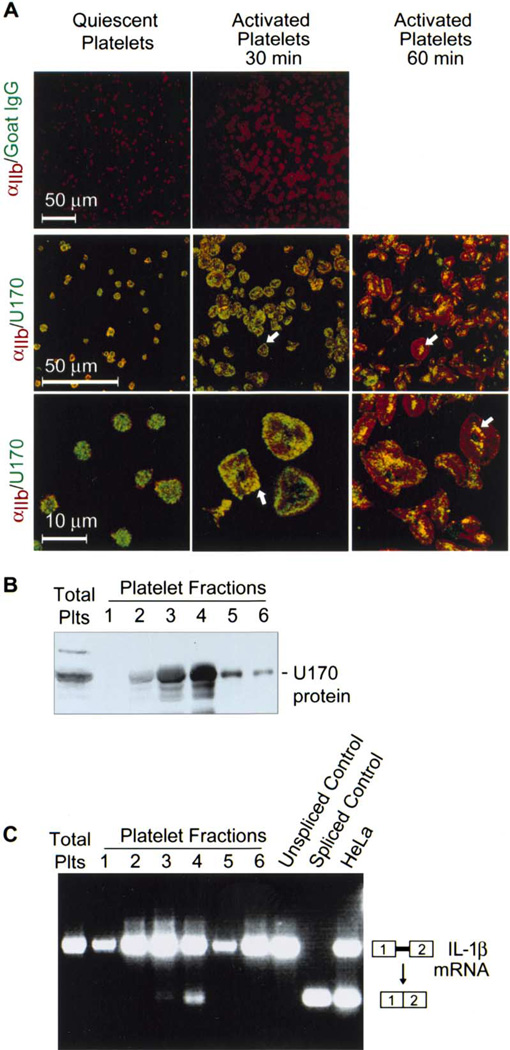

Figure 6. Platelet Extracts Splice In Vitro-Transcribed IL-1β pre-mRNA.

(A) This panel demonstrates immunolocalization of U1 70K protein in mature platelets. In the top panels, fixed platelets were incubated with nonimmune goat IgG and the antibody against the αIIb integrin subunit (red stain). In the subsequent panels, low-magnification (middle row) and high-magnification (bottom row) photomicrographs illustrate platelets that were costained with antibodies directed against U1 70K protein (green) and αIIb (red). Each panel is representative of six independent experiments.

(B) Platelet lysates were left unfractionated (total plts) or were separated into six fractions on sucrose gradients. U1 70K protein was detected by Western analysis.

(C) In vitro-transcribed IL-1β pre-mRNA was incubated with unfractionated platelet lysates (total plts), fractions 1–6, without platelet lysates (unspliced control) or with HeLa cell nuclear extracts (last lane). In vitro-transcribed intronless IL-1β mRNA (spliced control) was analyzed on the same gel as a positive control for spliced message. Gels in Figures 6B and 6C are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

The human spliceosome is requisite for gene expression because it removes nontranslatable introns from newly transcribed pre-mRNAs (Maniatis and Reed, 2002). The spliceosome functions within nuclear boundaries, and there has been no indication that splicing takes place in the extranuclear milieu of mammalian cells. Here we demonstrate that platelets, anucleate cytoplasts that regulate thrombosis and inflammation, possess essential splicing factors that process resident pre-mRNAs in response to external cues. Collectively, these data point to new concepts not formerly considered. From a general perspective, they identify a novel mode of nuclear-independent gene expression whereby eukaryotic cells can rapidly alter their message profile in response to exogenous stimulation. In the case of megakaryocytes, these data also indicate that splicing can be uncoupled from transcription and that pre-mRNAs are distributed to the cytoplasm by mechanisms that are yet to be defined. They also demonstrate that megakaryocytes distribute functional nuclear constituents to platelets during thrombopoiesis, an unprecedented finding since platelets are specialized anucleate cells. Signal-dependent splicing provides platelets with a novel mechanism to alter their pool of translatable messages, an important mode of gene regulation that expands the recently discovered capacity of this cell to translate a subset of mature mRNAs into biologically relevant proteins in response to cellular activation (Brogren et al., 2004; Lindemann et al., 2001a; Weyrich et al., 1998).

Splicing of eukaryotic precursor messenger RNAs (pre-mRNAs) involves the excision of introns from the pre-mRNA and ligation of flanking exons to produce a mature, translatable mRNA (Maniatis and Reed, 2002). Splicing is controlled by the spliceosome, a complex that is composed of five small ribonucleoproteins (snRNP), and each snRNP contains a small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and several proteins (Zhou et al., 2002a). There are also numerous auxiliary proteins that function cooperatively with U snRNPs to process pre-mRNAs (Black, 2003; Zhou et al., 2002a). Although the exact makeup of the platelet spliceosome is not completely defined, our observations demonstrate that platelets possess functional splicing components when assays similar to those used with model cell lines are employed (Mayeda and Krainer, 1999). At a minimum, platelets contain endogenous pre-mRNAs, all of the U snRNAs, and other requisite splicing factors (U1 70K protein, U2AF65, SF2/ASF, SRm160, SMN, SmBB′, and SmD1).

In quiescent platelets, translation of mature mRNAs such as B cell lymphoma 3 and IL-1β is repressed until the cells are appropriately stimulated (Lindemann et al., 2001a; Weyrich et al., 1998). Pre-mRNA splicing in platelets is likewise signal dependent, held in check until the cell is stimulated. Previous reports indicate that extracellular cues regulate alternative splicing in nucleated cells, suggesting that outside-in signals are recognized by intracellular splicing effectors (Matter et al., 2002; Xie and Black, 2001). However, these signaling events occur at the transcription phase as pre-mRNAs are spliced into mature messages. In contrast, the mechanisms we identified in platelets involve signaling to post-transcriptional checkpoints. While signal-dependent extranuclear splicing may be a unique feature of platelets, it is possible that cytoplasmic pre-mRNA splicing may also occur in cells such as neurons. Neu-ronal outgrowth resembles proplatelet morphogenesis (Italiano and Shivdasani, 2003), and posttranscriptional gene expression can be spatially localized to synaptic junctions (Martin, 2004).

In addition to being transcribed but not spliced, IL-1β pre-mRNA is distributed to the cytoplasm of mature megakaryocytes so it can eventually be packaged into platelets. This finding was unexpected because, if introns are not excised from mRNAs, the transcripts are generally thought to be degraded in the nucleus, an in vivo safeguard that prevents unwarranted translation of gene products that jeopardize cellular function (Reed and Magni, 2001). Although the mechanisms remain undefined, megakaryocytes and platelets have developed a system that circumvents this regulatory feature in a transcript-selective fashion. In addition to the IL-1β pre-mRNA, we found that other intronic messages are captured by trimethylguanosine immunoprecipitates in these cells. Some of these pre-mRNAs include tissue factor and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (data not shown). Both tissue factor and HMGB1 pre-mRNAs are spliced into mature messages by platelets in a signal-dependent fashion (our unpublished data). Several studies have recently demonstrated that quiescent platelets retain a surprisingly large set of megakaryocyte-derived mRNAs that are stably expressed, diverse, and in some cases translatable (Bahou and Gnatenko, 2004; Lindemann et al., 2001a, 2001b; McRedmond et al., 2004). These analyses are largely based on standard microarray procedures that are not optimized to detect intronic messages; therefore, message profiles in platelets may be more extensive and diverse than previously recognized. Further characterization of the portfolio of platelet pre-mRNAs may reveal additional patterns of splicing into predicted or alternative messages that code for inflammatory and thrombotic proteins. Additionally, only subsets of platelet messages contain introns (Figure S4), indicating differential handling and the possibility of novel forms of selection in megakaryocytes.

Identification of a functional spliceosome in platelets indicates that megakaryocyte nuclei may influence functional responses of mature circulating platelets in ways not previously considered. The prevailing tenet is that polyploid megakaryocyte nuclei serve as transcription factories to facilitate increases in cell mass required to assemble hundreds of individual platelets. Our observations demonstrate that essential components of the megakaryocyte spliceosome are also distributed to platelets during thrombopoiesis, altering dogma that platelets are devoid of functional nuclear constituents (Ravid et al., 2002) and providing a mechanism for regulated modification of the platelet transcriptome beyond the stage of proplatelet formation.

The human spliceosome is one of the most complex cellular machines characterized so far, consisting of more than 100 proteins and specialized nuclear RNAs (Zhou et al., 2002a). Possession of such a daedal unit by platelets demonstrates remarkable specialization and intricate information distribution from the megakaryocyte to the terminally differentiated platelet. Whether the spliceosome is translocated out of the megakaryocyte nucleus by regulated nuclear export or, in contrast, is differentially localized to the cytoplasm by inhibition of nuclear import is not known. Passive movement via breaks in the nuclear envelope is also possible because megakaryocytes undergo endomitosis to become polyploid, a process that weakens the nuclear envelope as it disassembles and reassembles with each endomitotic cycle (Italiano and Shivdasani, 2003). However, the nuclear envelope is ultrastructurally intact in megakaryocytes with proplatelet extensions (Figure 1B). Furthermore, spliceosomal components are found in the nucleus throughout proplatelet formation, suggesting that splicing factors do not leak into the cytoplasm in an uncontrolled fashion.

Eukaryotic cells use a variety of gene expression mechanisms to diversify and increase their proteomes. One level of control occurs at pre-mRNA splicing, a step that heretofore has been structurally and functionally associated with the nucleus. Our demonstration that pre-mRNA splicing can also occur in an environment devoid of a nucleus, the cytoplasmic milieu of activated human platelets, identifies an important extension of the regulatory repertoire of eukaryotic cells. In addition, it establishes additional diversity in the functional properties and capability for phenotypic alteration in this remarkable, specialized blood cell.

Experimental Procedures

Cells

CD34+ progenitor cells were isolated from umbilical cord blood (IRB# 11919). The CD34+ cells were cultured in suspension with X Vivo-20 culture medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Maryland) that contained 50 ng/ml of thrombopoietin (Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, California) and 40 ng/ml of human stem cell factor (Biosource, Camarillo, California). At day 13, the cells were placed on immobilized human fibrinogen (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corporation, San Diego, California) to sort mature megakaryocytes capable of forming proplatelets over a 16 hr incubation period (M.M.D., N.D.T., C.C.Y., F.J.R., T.M.M., K.H.A., G.A.Z., and A.S.W., unpublished data).

Washed human platelets were isolated using methods that we have previously described (Weyrich et al., 1996), with the exception that contaminating leukocytes were always removed by CD45+ bead selection at the PRP stage. We were unable to detect any residual leukocytes in CD45-depleted preparations by hemocytometer counting and microscopy (Figure S5, middle panel); however, platelet counts were normally reduced by 20%–40%. The negatively selected platelets were resuspended in M199 serum-free culture medium for all studies (Lindemann et al., 2001a). The cells were either left quiescent or allowed to adhere to immobilized human fibrinogen (Calbiochem, La Jolla, California) in the presence of thrombin (0.05 U/ml; Sigma).

Human monocytes were isolated by countercurrent elutriation as previously described (Weyrich et al., 1996). HeLa S3 (CCL-2.2, ATCC) cells were grown in suspension using spinner flasks, and HeLa (CCL-2, ATCC) cells were grown on coverglass chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International Inc., Naperville, Illinois) in Dul-becco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS.

mRNA Detection Systems

RACE

Total platelet RNA was used to generate first-strand RACE-ready cDNA (Clontech, Palo Alto, California). Gene-specific primers for 5′-RACE were directed to exon 3 and exon 1 for IL-1β and αIIb, respectively. Gene-specific primers for 3#-RACE were directed to exon 7 and exon 25 for IL-1β and αIIb, respectively. RACE products were sequenced on an ABI3730 96-capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) using M13R and M13F primers.

Exon-Flanking RT-PCR

Studies to determine endogenous splicing in quiescent and activated platelets were done by PCR using primers flanking intron 1 of IL-1β. PCR for IL-1β was also conducted over each intron of the gene using primers that targeted flanking exons and conditions optimal for amplification of longer transcripts (see Figure 5C). In select studies, platelet RNA was treated with DNase 1 (Ambion Inc., Austin, Texas) and RNase 1 (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) to confirm that it was RNA. Parallel controls with in vitro-transcribed RNA and genomic DNA, isolated from human monocytes, were simultaneously analyzed.

Northern Analysis of U snRNAs

Total RNA was isolated from purified human platelets and cultured HeLa S3 cells as previously described (Weyrich et al., 1998). For Northern analysis, oligonucleotide riboprobes to the snRNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) were synthesized using mirVana miRNA Probe Construction Kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, Texas). The probe sequences were as follows: U1-GAGATACCATGATCACGAAGGCCTGTCTC; U2-GCTAAGATCAAGTGTAGTATCCCTGTCTC; U4-TGCAATATAGT CGGCATTGGCACCTGTCTC; U5-GGAACAACTCTGAGTCTTAACC CTGTCTC; and U6-AGAGAAGATTAGCATGGCCCCCCTGTCTC. Competition studies using cold oligonucleotides directed against each snRNA probe were done to control for specificity of the hybridization.

In Situ Detection of mRNAs and U snRNAs

Indirect or direct in situ PCR was used to detect IL-1β mRNA in megakaryocytes that were forming proplatelets and mature platelets, respectively. For indirect in situ PCR, megakaryocytes that were developing proplatelet extensions were fixed with 4% para-formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2 M HCl, and endogenous DNA was removed by DNase treatment. cDNA was generated by reverse transcription, and then the cDNA was amplified with primers specific for introns one, four, and six of IL-1β. Negative control samples received no MMLV reverse transcriptase during cDNA synthesis. After PCR amplification, the cells were refixed, prehybridized, and then hybridized with 400 ng/ml of their corresponding intronic DIG-labeled probe. Primers specific for intron one (5′-CAAGGATCCTGCTCCAGCTCTCCTAGCC-3′ and 5′-ACCGGTACC TGAGTGACTTCCCCATGACG-3′), four (5′-AAAAAGCTTAGGCTGG AAACCAAAGCAAT-3′ and 5′-AGCGGATCCTGGGGTGGCTAAGA ACACTG-3′), and six (5′-CCAAAGCTTGGAAAAGCTGGGAACAG GTC-3′ and 5′-GAAGGATCCGCTGAGAAAGCTGGAGGTGA-3′) were used to generate the DIG-labeled probes. After a series of wash steps, an anti-DIG alkaline peroxidase (anti-DIG-AP) antibody was incubated with each sample, and hybridized signals were detected with an NBT/BCIP colorimetric reaction (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany).

For direct in situ PCR analysis, platelets were fixed with paraform-aldehyde, permeabilized, and treated with DNase as described above. In each study, the initial cDNA template was generated by reverse transcription, and then endogenous RNA was removed using RNase ONE. This step was critical to reduce background because we found that DIG-labeled dNTPs bind with high efficiency to endogenous RNA in platelets (data not shown). After RNase treatment, the cDNA generated in quiescent platelets was amplified in the presence of DIG-labeled dNTPs using primers specific for intron one (5′-CAAGGATCCTGCTCCAGCTCTCCTAGCC-3′ and 5′-ACCGGTACCTGAGTGACTTCCCCATGACG-3′). In the case of adherent platelets, the cDNA was amplified in the presence of DIG-labeled dNTPs using primers that targeted exons one (5′-CGAGG CACAAGGCACAACAG-3′) and four (5′-GCATCTTCCTCAGCTTG TCC-3′), respectively. These exonic primers allowed us to detect the spliced product (307 bp), but not the intronic product (3326 bp), by normal PCR methods. Negative control samples received no MMLV reverse transcriptase during the initial cDNA synthesis step. After the cDNA products were amplified in the presence of DIG-labeled dNTPs, the cells were refixed, and the labeled dNTPs were detected as described above.

U snRNAs in megakaryocytes, megakaryocytes with proplatelet extensions, mature platelets, or HeLa cells were detected with an antibody directed against the 2,2,7-trimethylguanosine cap (Calbiochem, La Jolla, California). The methods used to detect U snRNAs with anti-TMG parallel the procedures described below for immunocytochemical detection of splicing proteins (see below).

In Vitro Splicing Assay

HeLa nuclear extracts competent for splicing were obtained from ProteinOne Inc. (College Park, Maryland). Platelet extracts were isolated using a modified protocol designed for HeLa cells (Mayeda and Krainer, 1999). In brief, adherent platelets were lysed by nitrogen cavitation bombing at 1200 psi for 5 min. The soluble lysate was placed on a 30%–60% sucrose step gradient made in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 20% (v/v) glycerol, 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 0.5 mM DTT, and the gradient was centrifuged at 34,900 rpm for 3 hr in a SwTi40 rotor. Six cellular fractions were collected and used for in vitro splicing experiments.

A cDNA template of IL-1β containing intron one was made, incorporating a T3 promoter and poly-A tail, by PCR (forward primer, AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGAACCTCTTCGAGGCACA; reverse primer, TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTCCTGTAATAAGCCATCATTTCAC). In vitro-transcribed IL-1β pre-mRNA was mixed with 15 µl of platelet fractions or HeLa cell nuclear extract, 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 1 mM ATP, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.6% (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol (total volume of the mixture = 25 µl). The reaction was incubated for 4 hr at 30°C, the RNAwas isolated and reversed transcribed and the cDNA was then amplified by PCR using primers specific for exon one and two, and the PCR products were TA cloned and sequenced.

Protein Detection Systems

Western blot and immunocytochemical analysis was conducted as previously described (Weyrich et al., 1998). For these studies, antibodies directed against IL-1β (sc-1250), U1 70K protein (sc-9571), SRm160 (sc-10990), and αIIb integrins (sc-15328) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, California). The antibodies against Sm BB’ and Sm D1 were from Progen (Heidelberg, Germany). The anti-SMN antibody was from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, Kentucky), and the antibodies directed against U2AF65 and SF2/ASF were from Zymed (San Francisco, California). Specificity of the immunocytochemistry studies was confirmed by peptide quenching of the antibody, parallel studies with nonimmune IgG, or deletion of the primary antibody.

Ultrastructural Analyses

Scanning Electron Microscopy

Megakaryocytes and proplatelets that extend from megakaryocytes were fixed for 24 hr with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 24 hr. The fixed cells were then rinsed with sodium cacodylate and post-fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated with a graded series of ethanol, and then dried in hexamethyldisalizane. The samples were subsequently mounted on colloidal graphite, sputter coated, and visualized using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi S2460 N, San Jose, California).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

CD34+ stem-cell-derived megakaryocytes were placed on fibrino-gen-coated acylar for ultrastructural observation. After 1 or 16 hr, the cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde/1% paraformaldehyde in cacodylate buffer followed by postfixation with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydration in a graded acetone series, embedment in resin, and thin sectioning with a diamond knife (Albertine et al., 1999). A Hitachi H-7100 transmission electron microscope was used to observe and photograph the thin sectioned cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Melvin M. Denis (June 14, 1972–December 11, 2004) was killed in an avalanche while this manuscript was being written. His tragic death leaves a void in the community of scholars in our group and institution, and his contributions to biomedical investigation will be greatly missed in the future. He was supported by a physician-scientist training award from the American Diabetes Association (ADA PID2206052). This manuscript was also supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL-66277 to A.S.W., HL-44525 to G.A.Z., HL-44513 to T.M.M., HL-62875 to K.H.A., and HL-75507 to L.W.K.), an Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association (A.S.W.), the Children’s Health Research Center of the University of Utah (CHRCDA awards to C.C.Y. and F.J.R.) and by Families of Spinal Muscular Atrophy (KJS). C.C.Y. is a member of the Fellowship-to-Faculty Transition Program at the University of Utah, which is supported in part by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Biomedical Research Support Program for Medical Schools. Dr. Schwertz was supported by a Deutsche Forschungs Gemeinschaft (DFG) grant (SCHW 1167/1-1). We would also like to thank the Labor and Delivery Staff of Cottonwood Hospital and the University of Utah Hospitals and Clinics for collecting cord blood for megakaryocyte differentiation studies, Donnie Benson and Jessica Phibbs for blood pick-up and delivery, and Jason Foulks for providing cell cultures. We also thank Chris Rodesch and Nancy Chandler and the University of Utah School of Medicine Fluorescent Microscopy and Research Microscopy Facilities for technical assistance. Lastly, we thank Diana Lim for preparation of the figures.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Data include six figures and can be found with this article online at http://www.cell.com/cgi/content/full/122/3/379/DC1/.

References

- Albertine KH, Jones GP, Starcher BC, Bohnsack JF, Davis PL, Cho SC, Carlton DP, Bland RD. Chronic lung injury in preterm lambs. Disordered respiratory tract development. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999;159:945–958. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9804027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahou WF, Gnatenko DV. Platelet transcriptome: the application of microarray analysis to platelets. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2004;30:473–484. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-833482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe BJ, Issner R, Nickerson JA, Sharp PA. A coactivator of pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev. 1998;12:996–1009. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogren H, Karlsson L, Andersson M, Wang L, Erlinge D, Jern S. Platelets synthesize large amounts of active plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. Blood. 2004;104:3943–3948. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley BR, Hertel KJ, Maniatis T. The role of U2AF35 and U2AF65 in enhancer-dependent splicing. RNA. 2001;7:806–818. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201010317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig J, Italiano J., Jr The birth of the platelet. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;1:1580–1586. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings ML, Krainer AR. Pre-mRNA splicing in the new millennium. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:302–309. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hato T, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ. Integrin αIIbβ3 and platelet aggregation. In: Michelson AD, editor. Platelets. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Italiano JE, Jr, Shivdasani RA. Megakaryocytes and beyond: the birth of platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;1:1174–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Italiano JE, Jr, Lecine P, Shivdasani RA, Hartwig JH. Blood platelets are assembled principally at the ends of proplatelet processes produced by differentiated megakaryocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:1299–1312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrous N, Kaempfer R. Induction of human interleukin-1 gene expression by retinoic acid and its regulation at processing of precursor transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:23141–23149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochetov AV, Ischenko IV, Vorobiev DG, Kel AE, Babenko VN, Kisselev LL, Kolchanov NA. Eukaryotic mRNAs encoding abundant and scarce proteins are statistically dissimilar in many structural features. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:351–355. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohtz JD, Jamison SF, Will CL, Zuo P, Luhrmann R, Garcia-Blanco MA, Manley JL. Protein-protein interactions and 5′-splice-site recognition in mammalian mRNA precursors. Nature. 1994;368:119–124. doi: 10.1038/368119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krainer AR. Pre-mRNA splicing by complementation with purified human U1, U2, U4/U6 and U5 snRNPs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9415–9429. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann S, Tolley ND, Dixon DA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Weyrich AS. Activated platelets mediate inflammatory signaling by regulated interleukin 1beta synthesis. J. Cell Biol. 2001a;154:485–490. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann S, Tolley ND, Eyre JR, Kraiss LW, Mahoney TM, Weyrich AS. Integrins regulate the intracellular distribution of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E in platelets. A checkpoint for translational control. J. Biol. Chem. 2001b;276:33947–33951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann SW, Yost CC, Denis MM, McIntyre TM, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA. Neutrophils alter the inflammatory milieu by signal-dependent translation of constitutive messenger RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7076–7081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401901101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Reed R. The role of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles in pre-mRNA splicing. Nature. 1987;325:673–678. doi: 10.1038/325673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Reed R. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature. 2002;416:499–506. doi: 10.1038/416499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KC. Local protein synthesis during axon guidance and synaptic plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004;14:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter N, Herrlich P, Konig H. Signal-dependent regulation of splicing via phosphorylation of Sam68. Nature. 2002;420:691–695. doi: 10.1038/nature01153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda A, Krainer AR. Preparation of HeLa cell nuclear and cytosolic S100 extracts for in vitro splicing. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999;118:309–314. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-676-2:309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEver RP. Properties of GMP-140, an inducible granule membrane protein of platelets and endothelium. Blood Cells. 1990;16:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRedmond JP, Park SD, Reilly DF, Coppinger JA, Maguire PB, Shields DC, Fitzgerald DJ. Integration of proteomics and genomics in platelets: a profile of platelet proteins and platelet-specific genes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2004;3:133–144. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300063-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni L, Yong J, Dreyfuss G. Essential role for the SMN complex in the specificity of snRNP assembly. Science. 2002;298:1775–1779. doi: 10.1126/science.1074962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravid K, Lu J, Zimmet JM, Jones MR. Roads to polyploidy: the megakaryocyte example. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002;190:7–20. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R, Magni K. A new view of mRNA export: separating the wheat from the chaff. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:E201–E204. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-e201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romac JM, Graff DH, Keene JD. The U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) 70K protein is transported independently of U1 snRNP particles via a nuclear localization signal in the RNA-binding domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:4662–4670. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby SW, Abelson J. An early hierarchic role of U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein in spliceosome assembly. Science. 1988;242:1028–1035. doi: 10.1126/science.2973660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrich AS, Elstad MR, McEver RP, McIntyre TM, Moore KL, Morrissey JH, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Activated platelets signal chemokine synthesis by human mono-cytes. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:1525–1534. doi: 10.1172/JCI118575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrich AS, Dixon DA, Pabla R, Elstad MR, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Signal-dependent translation of a regulatory protein, Bcl-3, in activated human platelets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:5556–5561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrich AS, Lindemann S, Zimmerman GA. The evolving role of platelets in inflammation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;1:1897–1905. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrich AS, Lindemann S, Tolley ND, Kraiss LW, Dixon DA, Mahoney TM, Prescott SM, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA. Change in protein phenotype without a nucleus: translational control in platelets. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2004;30:493–500. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-833484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will CL, Luhrmann R. Spliceosomal UsnRNP biogenesis, structure and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2001;13:290–301. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Maniatis T. Specific interactions between proteins implicated in splice site selection and regulated alternative splicing. Cell. 1993;75:1061–1070. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90316-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Black DL. A CaMK IV responsive RNA element mediates depolarization-induced alternative splicing of ion channels. Nature. 2001;410:936–939. doi: 10.1038/35073593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong J, Pellizzoni L, Dreyfuss G. Sequence-specific interaction of U1 snRNA with the SMN complex. EMBO J. 2002;21:1188–1196. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Licklider LJ, Gygi SP, Reed R. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome. Nature. 2002a;419:182–185. doi: 10.1038/nature01031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Sim J, Griffith J, Reed R. Purification and electron microscopic visualization of functional human spliceosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002b;99:12203–12207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182427099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.