Abstract

Psoriasis has been linked to cardiometabolic diseases, but epidemiological findings are inconsistent. We investigated the association between psoriasis and cardiometabolic outcomes in a German cross-sectional study (n=4.185) and a prospective cohort of German Health Insurance beneficiaries (n=1.811.098). A potential genetic overlap was explored using genome-wide data from >22.000 coronary artery disease (CAD) and >4.000 psoriasis cases, and with a dense genotyping study of cardiometabolic risk loci on 927 psoriasis cases and 3.717 controls. Controlling for major confounders, in the cross-sectional analysis psoriasis was significantly associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D, adjusted odd’s ratio OR=2.36; 95% confidence interval CI=1.26–4.41) and myocardial infarction (MI, OR=2.26, 95% CI=1.03–4.96). In the longitudinal study, psoriasis slightly increased the risk for incident T2D (adjusted relative risk RR=1.11; 95%CI=1.08–1.14) and MI (RR=1.14; 95%CI=1.06–1.22), with highest risk increments in systemically treated psoriasis, which accounted for 11 and 17 excess cases of T2D and MI per 10,000 person-years. Except for weak signals from within the MHC, there was no evidence for genetic risk loci shared between psoriasis and cardiometabolic traits. Our findings suggest that psoriasis, in particular severe psoriasis, increases risk for T2D and MI, and that the genetic architecture of psoriasis and cardiometabolic traits is largely distinct.

Introduction

Psoriasis is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases that affects 2–4% of the general population with, however, variations between and within countries (Parisi et al., 2013), and causes a significant social and pharmacoeconomic burden (Suarez-Farinas et al., 2012). Experimental data indicate that chronic skin inflammation has a systemic component, affects different metabolic pathways, and drives inflammation in other tissues (Wang et al., 2012). In line with this concept, epidemiological studies reported an elevated risk for inflammatory comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and metabolic diseases, in particular in younger individuals with severe psoriasis; i.e. those with a higher genetic component (Gelfand et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2013; Shaharyar et al., 2014). However, most published studies were carried out in selected populations and suffer from methodological limitations such as insufficient phenotyping and incomplete adjustment for potential confounders. Further, results on cardiometabolic risk factors associated with psoriasis are inconsistent (Armstrong et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2013; Samarasekera et al., 2013). Results from disease-by-disease gene mapping indicate a considerable overlap in the genetic basis of different immune-mediated diseases (Zhernakova et al., 2013), and data from candidate gene studies suggest that some genetic variants associated with the risk of inflammatory diseases, e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, also predispose to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (Ellinghaus et al., 2012; Krawczak et al., 2006; Lieb and Vasan, 2013). However, comprehensive analyses on the potential overlap in the genetic architectures of psoriasis and cardiometabolic traits are lacking. In the current study, we aimed to analyze the association between psoriasis and cardiometabolic risk factors and clinical disease outcomes using 2 different epidemiological datasets: the population-based KORA study (n=4.185) and data from German Health insurance beneficiaries (n=1.811.098). Furthermore, we performed comprehensive genetic analyses in order to assess whether and to which degree the genetic architectures of psoriasis and CVD overlap. To this end, we carried out in-silico analyses of genetic CAD and psoriasis risk variants identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in >22.000 CVD cases, >4.000 psoriasis cases and > 60.000 controls. In addition, we used the Metabochip® custom array to densely genotype and analyse established cardiometabolic risk loci in a set of 927 psoriasis cases and 3.717 controls.

Results

Cross-sectional association of psoriasis with cardiometabolic traits in KORA

The prevalence of psoriasis in the KORA study sample including German adults (n=4.185; mean age 56 years, 48,5% men) was 4.8%, which is slightly above the prevalence reported from German secondary healthcare data on adults of the same age range (4%, (Schafer et al., 2011). This might in part be attributable to mild cases that may not seek medical attention (Table I). In terms of the cardiovascular risk factor profile, individuals with psoriasis were less likely to be never smoker (36.7% vs. 45.4%), had a higher educational attainment (education ≥11y; 29.2% vs. 22.7%), higher waist circumference (98 vs. 93 cm) and higher levels of CRP (6.3 n/nL vs. 5.9 n/nL) and leukocyte count (1.7 vs. 1.2 mg/L) as compared to individuals without psoriasis. No statistically significant differences in BMI, blood pressure, total cholesterol-to-HDL cholesterol ratio or carotid intima-media thickness were observed between individuals with vs. without psoriasis. In multivariable linear regression analysis psoriasis was statistically significantly associated with waist circumference (β=1.70; 95% CI=0.14–3.26), T2D (OR=2.36; 95%CI=1.26–4.41) and MI (OR=2.26, 95%CI=1.03–4.96), but not with hypertension, metabolic syndrome, AP, nor peripheral arterial disease (PAD) (Table II, Table S1). No evidence for effect modification by age was observed (all P for interaction > 0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics1 of the analytical study population of KORA survey participants (n=4,185).

| No Psoriasis (n=3986) | Psoriasis (n=199) | P value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 56 (45, 67) | 56 (46, 65) | 0.971 |

| Male, n (%) | 1918 (48.1) | 110 (55.3) | 0.049 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Never | 1808 (45.4) | 73 (36.7) | 0.016 |

| Former | 1466 (36.8) | 87 (43.7) | 0.048 |

| Current | 712 (17.9) | 39 (19.6) | 0.534 |

| Education, n (%)3 | |||

| ≤ 9 y | 2075 (52.1) | 100 (50.3) | 0.619 |

| 10 y | 1001 (25.1) | 41 (20.6) | 0.151 |

| ≥ 11 y | 905 (22.7) | 58 (29.2) | 0.035 |

| Alcohol intake, g/d | 5.7 (0.0, 20.9) | 5.7 (0.0, 28.6) | 0.299 |

| Physical activity, n (%)4 | |||

| No activity | 933 (23.4) | 49 (24.6) | 0.623 |

| Low activity | 523 (13.1) | 32 (16.1) | 0.230 |

| Moderate activity | 1557 (39.1) | 75 (37.7) | 0.698 |

| High activity | 973 (24.4) | 43 (21.6) | 0.368 |

| BMI, kg/m2,5 | 26.9 (24.2, 30.1) | 27.6 (24.5, 30.4) | 0.117 |

| Waist circumference, cm6 | 93 (84, 103) | 98 (87, 105) | 0.003 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 123 (111, 136) | 123 (111, 136) | 0.727 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 76 (70, 84) | 77 (71, 84) | 0.423 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1704 (42.8) | 91 (45.7) | 0.407 |

| Hypertension treatment, n (%) | 1188 (29.8) | 60 (30.2) | 0.917 |

| Total cholesterol-to-HDL | 3.9 (3.1, 4.7) | 3.9 (3.3, 5.1) | 0.080 |

| cholesterol ratio | |||

| Lipid-lowering treatment, n (%) | 463 (11.6) | 29 (14.6) | 0.206 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 207 (5.2) | 21 (10.6) | 0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes treatment, n (%) | 169 (4.2) | 17 (8.5) | 0.004 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%)7 | 993 (35.2) | 51 (40.2) | 0.253 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 101 (2.5) | 11 (5.5) | 0.011 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%)8 | 196 (6.9) | 14 (9.0) | 0.315 |

| Angina pectoris, n (%)9 | 194 (4.9) | 12 (6.1) | 0.450 |

| Carotid intima-media thickness10 | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 0.684 |

| CRP, mg/L11 | 1.2 (0.6, 2.6) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.5) | 0.001 |

| Leukocytes, n/nL9 | 5.9 (5.0, 7.1) | 6.3 (5.1, 7.4) | 0.024 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Values are median (25th, 75th percentile) or n (percent).

Based on Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

n = 4180.

Defined as: no activity (no sports in summer or winter season), low activity (engaging in sports <1h/week in summer or winter season), moderate activity (engaging in sports 1–2 h/week regularly in summer or winter season), high activity (engaging in sports >2 h/week in summer and winter season).

n = 4167.

n = 4173.

n=2948.

n = 2990.

n = 4182.

Average of right and left common carotid artery; n=2646.

n = 3024.

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted beta coefficient or Odds Ratio (OR; 95% confidence interval in parentheses)1 for cardiometabolic outcomes by psoriasis status (n=4,185).

| Psoriasis, Beta Coefficient or OR (95%CI) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Continuous outcomes | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.51 (−0.14, 1.16)2 | 0.44 (−0.17, 1.05)3 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 2.03 (0.36, 3.70)4 | 1.70 (0.14, 3.26)5 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | −0.09 (−2.56, 2.38) | −0.04 (−2.49, 2.40)6 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 0.48 (−0.98, 1.95) | 0.67 (−0.78, 2.13)6 |

| Total cholesterol-to-HDL cholesterol ratio | 0.15 (−0.01, 0.31) | 0.16 (<0.01, 0.32)6 |

| Carotid intima-media thickness | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01)7 | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01)8 |

| CRP, mg/L | 0.46 (−0.46, 1.37)9 | 0.29 (−0.62, 1.20)10 |

| Leukocytes, n/nL | 0.20 (−0.06, 0.46)11 | 0.16 (−0.09, 0.41)12 |

| Dichotomous outcomes | ||

| Hypertension | 1.15 (0.83, 1.59) | 1.08 (0.77, 1.50)6 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 2.31 (1.41, 3.80) | 2.37 (1.40, 4.02)6 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 1.25 (0.85, 1.85)13 | 1.25 (0.85, 1.86)14 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2.29 (1.17, 4.46) | 2.26 (1.03, 4.96)6 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1.46 (0.82, 2.60)115 | 1.19 (0.64, 2.22)16 |

| Angina pectoris | 1.33 (0.72, 2.44)17 | 1.22 (0.65, 2.27)12 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Beta coefficient for continuous outcomes or OR for binary outcomes. Model 1 was adjusted for sex and age (continuous). Model 2 was adjusted for sex, age (continuous), smoking status (never, former, current), years of education (≤9 y, 10 y, or ≥11 y), alcohol intake (continuous), physical activity (no activity, low activity, moderate activity, high activity), systolic blood pressure (continuous; except systolic, diastolic blood pressure, hypertension and metabolic syndrome), hypertension treatment (no, yes; except hypertension and metabolic syndrome), type 2 diabetes (no, yes; except type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome), type 2 diabetes treatment (no, yes; except type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome), lipid-lowering treatment (no, yes; except metabolic syndrome).

n=4167.

n=4162.

n=4173.

n=4168.

n=4180.

n=2646.

n=2642.

n=3024.

n=3019.

n=4182.

n=4177.

n=2948.

n=2943.

n=2990.

n=2987.

n=4182.

Longitudinal association of psoriasis with incident cardiometabolic events in German Health Insurance beneficiaries

A total of 44.623 patients with prevalent psoriasis in 2005/2006 and 1.766.475 individuals without psoriasis were followed up for incident cardiometabolic endpoints from 2007 to 2012 with a median follow-up time of 6 years. Participant characteristics are provided in Table III. In the fully adjusted model, patients with psoriasis had a significantly increased relative risk for T2D (RR=1.11; 95% CI: 1.08–1.14), AP (RR= 1.27; 95% CI=1.20–1.34) and MI (RR=1.14; 95% CI=1.06–1.22) compared with patients without psoriasis (Table IV, Table S2). Adjusting for age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, and comorbidities, psoriasis accounted for an excess risk of 17.89 incident cases of T2D, 10.43 incident cases with AP, and 3.25 incident MIs per 10,000 person-years. The association of psoriasis with MI was not modified by age (p for interaction > 0.05). However, we observed effect modification by age for type 2 diabetes (p for interaction = 4.2x10−36), angina pectoris (p for interaction = 0.026), and stroke (p for interaction= 3.2x10−4). Specifically, we observed evidence for a decreasing strength of association between psoriasis and incident diabetes (multivariable adjusted RRs (95%CI) age ≤ 40 years 1.27 (1.06, 1.52); age 41–60 years 1.10 (1.04, 1.16); age > 60 years 1.04 (1.00, 1.07)). For stroke, stratified analyses do not suggest a qualitative or quantitative linear association (age ≤ 60 years 1.03 (0.89, 1.19); age 61–70 years 1.20 (1.07, 1.34); age > 70 years 1.07 (1.00, 1.13). The association between angina pectoris and psoriasis increased with increasing age categories (age ≤ 60 years 1.16 (1.04, 1.29); age 61–70 years 1.21 (1.08, 1.35); age > 70 years (1.25 (1.16, 1.35)).

Table 3.

Characteristics1 of the AOK Saxony database by psoriasis status (n=1,811,098).

| No Psoriasis (n= 1,766,475) |

Psoriasis |

P value2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No medication (n= 9,213) |

Exclusively topical medication (n= 31,139) |

Systemic medication (n= 4,271) |

Total (n= 44,623) |

Psoriasis vs no Psoriasis |

||

| Age (years) in 2005 | 49 (30, 68) | 57 (43, 70) | 61 (45, 72) | 54 (42, 66) | 59 (44, 71) | <1E-300 |

| Male, n(%) | 811,180 (45.9) | 4,384 (47.6) | 14,343 (46.1) | 2,020 (47.3) | 20,747 (46.5) | 0.016 |

| Hypertension, n(%)3,4 | 205,831 (19.5) | 1,063 (26.3) | 3,682 (28.9) | 580 (29.7) | 5,325 (28.4) | 1.3E-204 |

| Type 2 diabetes, n(%)3,5 | 120,507 (8.1) | 787 (11.3) | 2,860 (12.6) | 394 (12.0) | 4,041 (12.3) | 2.1E-162 |

| Myocardial infarction, n(%)3,6 | 20,103 (1.2) | 143 (1.6) | 574 (1.9) | 80 (1.9) | 797 (1.9) | 3.2E-39 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n(%)3,7 | 31,138 (1.8) | 234 (2.7) | 918 (3.1) | 103 (2.5) | 1,255 (3.0) | 1.8E-68 |

| Angina pectoris, n(%)3,8 | 32,350 (1.9) | 251 (3.0) | 959 (3.4) | 125 (3.2) | 1,335 (3.3) | 2.4E-82 |

| Stroke, n(%)3,9 | 41,778 (2.5) | 289 (3.3) | 1,134 (3.9) | 113 (2.7) | 1,536 (3.6) | 3.8E-54 |

| Obesity, n(%)3,10 | 102,601 (6.7) | 578 (7.8) | 2,172 (8.8) | 362 (10.8) | 3,112 (8.8) | 3.0E-53 |

| Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism and other lipidaemias, n(%)3,11 |

165,526 (11.8) | 1,045 (16.7) | 3,584 (16.8) | 517 (17.1) | 5,146 (16.8) | 4.3E-158 |

| Mortality, n(%)3 | 174,642 (9.9) | 1,076 (11.7) | 4,272 (13.7) | 371 (8.7) | 5,719 (12.8) | 1.3E-92 |

Values are median (25th, 75th percentile) or n (percent).

Based on Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for age and Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Incidence in 2007–2012.

n=1,075,121.

n=1,514,541.

n=1,773,833.

n=1,751,381.

n=1,715,269.

n=1,746,355.

n=1,567,015.

n=1,436,629.

Table 4.

Multivariable-adjusted Risk Ratios (RR; 95% confidence interval in parentheses) and excess risk per 10,000 person years1 for cardiometabolic diseases by psoriasis status (n= 1,811,098).

| RR (95%CI) |

Excess risk per 10,000 person-years6 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Type 2 diabetes 2007–20122 | ||||

| Psoriasis (present vs. absent) | 1.21 (1.18, 1.25) | 1.11 (1.08, 1.14) | 34.16 | 17.89 |

| Psoriasis, no medication | 1.16 (1.08, 1.23) | 1.06 (0.99, 1.13) | 26.03 | 9.76 |

| Psoriasis, exclusively topical medication | 1.21 (1.17, 1.25) | 1.10 (1.07, 1.14) | 34.16 | 16.27 |

| Psoriasis, systemic medication | 1.38 (1.26, 1.51) | 1.25 (1.14, 1.37) | 61.81 | 40.67 |

| Myocardial infarction 2007–20123 | ||||

| Psoriasis (present vs. absent) | 1.24 (1.15, 1.33) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 5.58 | 3.25 |

| Psoriasis, no medication | 1.10 (0.94, 1.30) | 1.01 (0.86, 1.19) | 2.32 | 0.23 |

| Psoriasis, exclusively topical medication | 1.23 (1.14, 1.34) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.23) | 5.34 | 3.02 |

| Psoriasis, systemic medication | 1.62 (1.30, 2.01) | 1.48 (1.19, 1.84) | 14.40 | 11.15 |

| Angina pectoris 2007–20124 | ||||

| Psoriasis (present vs. absent) | 1.38 (1.30, 1.45) | 1.27 (1.20, 1.34) | 14.68 | 10.43 |

| Psoriasis, no medication | 1.29 (1.14, 1.46) | 1.17 (1.04, 1.33) | 11.21 | 6.57 |

| Psoriasis, exclusively topical medication | 1.38 (1.29, 1.47) | 1.28 (1.20, 1.36) | 14.68 | 10.82 |

| Psoriasis, systemic medication | 1.57 (1.32, 1.86) | 1.43 (1.21, 1.70) | 22.03 | 16.62 |

| Stroke 2007–20125 | ||||

| Psoriasis (present vs. absent) | 1.17 (1.11, 1.23) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.17) | 8.34 | 5.39 |

| Psoriasis, no medication | 1.10 (0.99, 1.24) | 1.05 (0.94, 1.18) | 4.90 | 2.45 |

| Psoriasis, exclusively topical medication | 1.19 (1.12, 1.26) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.20) | 9.32 | 6.37 |

| Psoriasis, systemic medication | 1.14 (0.95, 1.36) | 1.08 (0.90, 1.29) | 6.86 | 3.92 |

Model 1 was adjusted for sex, age (continuous). Model 2 was adjusted for sex; age (continuous); hypertonia (no, yes); type 2 diabetes (no, yes; except type 2 diabetes); obesity and disorders of lipoprotein metabolism and other lipidaemias (no, yes).

n=1,514,541.

n=1,773,833.

n=1,715,269.

n=1,746,355.

Excess risks calculated based on adjusted risk ratios.

In sensitivity analyses the risk increments were markedly higher in psoriasis patients receiving systemic treatment, which is often used as a proxy for severe psoriasis (Gelfand et al., 2006) (Table IV). Systemically treated psoriasis (see Table S3 in the Supplemental Data) accounted for approximately 41, 17 and 11 excess cases of AP, MI and T2D, respectively, per 10,000 person-years (Table IV).

Association analysis of established CAD risk SNPs with psoriasis

Except for two polymorphisms which map to HLA-C/HCG27 (rs2894181) and C6orf10/BTNL2 (rs6932542) none of the established CAD-SNPs was significantly associated with psoriasis after conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (see Table S4 in the Supplemental Data). Both MHC polymorphisms represent signals independent from the major psoriasis HLA-C*0602 risk allele, an observation reported before (Davies et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2009). Effects on CAD and psoriasis risk were into the same direction, but the reported effect sizes on CAD are modest (OR<1.2) (Lu et al., 2012).

Association analysis of established psoriasis risk SNPs with CAD

None of the established psoriasis risk SNPs was significantly associated with CAD after conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (see Table S5 and Figure S1 in the Supplemental Data). Suggestive evidence for association (p<0.05) was observed for three SNPs (rs1265181, rs12191877, rs10484554) at the major psoriasis locus PSORS-1 in the MHC. These three polymorphisms are in moderate to strong LD with the psoriasis HLA-C*0602 risk allele (r2≥0.6) and show weak opposing effects on CAD risk. Further suggestive evidence for association with CAD was observed for a variant near the interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3 (ILF3) and Coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1) genes (P =1.74x10−3).

Proportion of CAD SNPs associated with psoriasis and vice versa

In 61.7% of the investigated psoriasis SNPs the same risk alleles showed a positive association (OR>1) with CAD, which is in the range of expectation by chance (P=0.1439). In the reverse comparison, in 65.5% of the CAD SNPs the same risk allele showed a positive association with psoriasis, which is slightly more than the expected 50% by chance (P=0.030). However, none of these SNPs showed nominally significance (P<0.05).

Metabochip analysis in the psoriasis case-control study

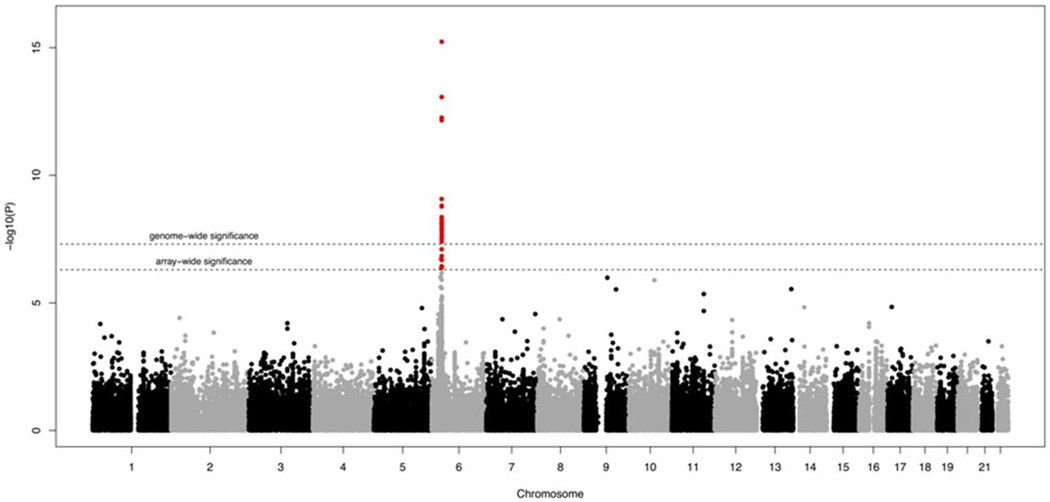

Multiple SNPs from within the MHC locus displayed a strong association with psoriasis. The top SNP was rs10484554 (see Table S6 in the Supplemental Data), which tags the HLA-C*0602 risk allele (P =5.84x10−16, OR=2.03, 95% CI=1.86–2.20) (Figure 1). Conditioning upon rs10484554, the P values for all other SNPs at the MHC locus were substantially mitigated, which, however could be due to a lack of power given that robust evidence for several independent signals from within the MHC has been provided in previous studies (Knight et al., 2012). No non-MHC SNP exceeded the conservative array-wide significance level (P = 5.03x10−7). Suggestive evidence for association (P<5x10−6) was observed for 5 loci comprising the genes TMEM2, ZMIZ1, ARHGAP42 and two intergenic regions (see Table S7 in the Supplemental Data). Of the 43 previously reported psoriasis susceptibility loci (Hindorff et al.) 32 reached nominal significance (p<0.05) in the Metabochip analysis. No association was seen for the loci IL28RA, LCE3D, B3GNT2, ZDHHC23, TNFAIP3, TAGAP, ELMO1, ZC3H12C, SDC4 and UBE2l3, which, however, are sparsely covered by the Metabochip (see Table S8 in the Supplemental Data).

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of Metabochip results on psoriasis.

Discussion

Main findings

Using different large-scale epidemiological and genetic datasets, we assessed the interrelation of psoriasis and cardiometabolic outcomes as well as a potential common genetic underpinning of these traits. In both our cross-sectional and cohort study psoriasis was an independent yet modest risk factor for T2D and MI. Sensitivity analyses in the cohort study provided evidence for a “dose-response” association since severe psoriasis was associated with higher risks for T2D, AP and MI relative to mild psoriasis. Except for two psoriasis risk loci from within the MHC with small effects (OR<1.2) on CAD risk, none of the established psoriasis risk polymorphisms showed a robust association with CAD, and no gene variant previously associated with CAD was robustly associated with psoriasis. Likewise, while confirming the vast majority of known psoriasis risk loci, our dense genotyping study did not indicate that validated loci for cardiometabolic traits have a notable effect on psoriasis risk, although we cannot rule out that we missed rare variants or variants with minor effects.

In the context of the published literature

The first study that claimed an increased cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis stems from a large prospective, population-based cohort study using UK electronic medical record data (Gelfand et al., 2006). Subsequently, a series of multiple studies reported a higher risk for various cardiometabolic traits (including hypertension, T2D, hyperlipidemia, hypercholesterolemia and obesity) in patients with psoriasis, in particular those with severe and widespread forms (Kimball and Wu, 2009; Langan et al., 2012; Yeung et al., 2013). However, most of these studies were hospital-based and investigated selected patient groups, and multiple biases including publication bias must be considered when interpreting them (Nijsten and Wakkee, 2009; Stern and Nijsten, 2012). Further, the results in the published literature are not unambiguous. E.g., in the population-based Rotterdam Study and in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, psoriasis was not associated with the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke or heart failure (Dowlatshahi et al., 2013a), neither fasting glucose (Love et al., 2011), and in the Nurses’ Health Study the association of psoriasis with T2D was very modest and only among younger patients (Li et al., 2012). Finally, in line with our results meta-analyses indicated that the association of psoriasis with cardiometabolic diseases is rather modest and driven by severe cases (Armstrong et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2013; Samarasekera et al., 2013). The degree to which the association is directly attributable to psoriasis remains controversial.

While providing sufficient sample sizes and statistical power, routine data from health insurance databases commonly suffer from incomplete information on important confounders and potential detection, diagnostic and observation bias (Swart et al., 2014). In turn, population-based cross-sectional studies capture many outcomes and risk factors, but are often underpowered to analyse diseases with a low prevalence, and do not allow to make causal inference nor to establish the time sequence of events. In the present manuscript, we used both approaches in a complementary fashion, and analyzed primary cross-sectional data from the well characterized KORA survey as well as secondary prospective data from the AOK Saxony administrative healthcare database. In the cross-sectional analysis, psoriasis was significantly associated with T2D and MI, and no substantial attenuation upon adjustment for multiple possible confounders was observed.

In line with the results from the cross-sectional analysis, adjusting for major known risk factors in the prospective cohort study for psoriasis at large after a median follow up time of 6 years we observed a moderately increased relative risk for incident T2D and MI, as well as an increased risk for AP, which translates in estimated excess risks of 18, 11 and 3 cases of T2D, AP and MI, respectively, per 10,000 person-years.

A recent in-silico analysis on 363 SNPs in 4.482 psoriasis cases and 7.463 controls reported statistically significant associations of psoriasis with seven SNPs primarily implicated in dyslipidemia, hypertension and CAD (Lu et al., 2013). In our more comprehensive genetic approach including both large-scale GWAS data for psoriasis and CAD as well as high density genotyping data for roughly 100.000 cardiometabolic candidate loci, we did not observe robust associations of psoriasis with genetic risk markers primarily associated with cardiometabolic risk factors and related endpoints, including CAD and T2D. On a similar note, genetic psoriasis loci displayed no evidence for association with CAD in the CARDIoGRAM data set with more than 20,000 CAD cases and approximately 60,000 controls, except for very modest effects of markers tagging the HLA-Cw6 allele. It has to be kept in mind, though, that we focused on relatively common genetic variation. Growing evidence indicates that inflammation participates centrally in all stages of CAD and that thus variations in MHC genes, which regulate inflammation and T-cell responses, might have effects across inflammatory traits. In particular, BTNL2, which has been linked with various immune-related diseases (Clancy et al., 2010; Jin et al., 2011; Valentonyte et al., 2005), probably functions as a T cell costimulatory molecule. Furthermore, T-cell-activation regulated by costimulatory molecules has been implicated in both psoriasis and CAD (Lahoute et al., 2011). Of note, we focused on common variants, and additional studies are warranted to assess the significance of rare genetic variants.

Given the lack of evidence for a joint genetic basis of psoriasis and cardiometabolic traits and the consistently observed “dose–response” relationship we speculate that shared non-genetic risk factors not captured in our analysis and/or an increased inflammatory status of (severe) psoriatics might contribute to the slightly increased risk for comorbidities, e.g. inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins and tumour necrosis factor-alpha which increase oxidative stress and drive insulin resistance (Dowlatshahi et al., 2013b). The latter hypothesis would also be supported if early and efficient psoriasis treatment lowered risk for comorbidities in a prospective setting. Some support for this hypothesis is provided by a recent large retrospective analysis demonstrating a reduced risk for T2D in patients with RA or psoriasis who had received a TNF inhibitor (Solomon et al., 2011), compared to patients on other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. However, it has to be considered that even for severe psoriasis the excess risks for cardiometabolic diseases reported and observed here are very modest in absolute terms, and that so far, the potential impact of early intervention with anti-psoriatic agents has not been sufficiently investigated.

Strengths and limitations

Major strengths of our epidemiological analysis are the use of both a cross-sectional and prospective population-based approach. In the cross-sectional analysis, psoriasis assessment and cardiometabolic risk profiling was stringent, known potential confounders were taken into account, and both soft and hard end-points were analyzed. However, the number of patients with psoriasis and cardiovascular events was modest, and no stratification by psoriasis disease severity was possible. The prospective cohort was sufficiently powered to track and compare incident disease events in health care beneficiaries with and without psoriasis, but the observation period was relatively short. Since no direct information on disease severity was available, systemic therapy was used as surrogate marker. Further, although health administrative data appears to be rather reliable for MI and T2D (Muggah et al., 2013), and we used stringent outcome definitions, remaining limitations of disease ascertainment accuracy and surveillance bias must be taken into account. One related limitation is that exact time-to-event data could not be inferred from the database utilized. We therefore assumed that every participant adds 6 years of person-time when estimating excess risks, which may be an overestimation and thus lead to a conservative estimate of the true excess risk.

Conclusions

Psoriasis at large appears to be an independent yet modest risk factor for T2D and MI. For the subgroup of patients with severe psoriasis, however, risk increments are considerably higher. Thus, while on a population level the association between severe psoriasis and CVD is rather modest and the increase in absolute disease risk is minor, this risk might be clinically relevant in individual patients. The excess comorbidity cannot fully be attributed to major known environmental/lifestyle determinants of MI and T2D risk and appears to be not due to shared genetic risk factors. Prospective and sufficiently large cohort studies are needed to further clarify the relationship between psoriasis and cardiometabolic traits, and randomized controlled trials should test whether and which psoriasis treatment has beneficial effects regarding comorbidity risk.

Methods

Study samples

KORA sample

Within the MONICA/KORA (Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease/Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg, southern Germany) framework, different population-based surveys were performed. The present analysis included KORA-C, which is a subset of the KORA S3 as well as the KORA F4 survey conducted in 1994/95 and 1999/2001, respectively. The design and selection criteria for these surveys have been described previously (Holle et al., 2005). Participants received a standardized interview and a self-administered questionnaire to gather information on medical history, and a physical and dermatological (F4) examination were performed and blood was drawn. Additional information on data ascertainment strategy of the KORA F3 and F4 study is provided (see Methods section in this article’s Supplemental Data). A total of 4,185 individuals with full phenotypic information were used for the present cross-sectional analysis.

German Health insurance beneficiaries

For the prospective cohort analyses relating psoriasis to incident type 2 diabetes and myocardial infarction, we utilized the AOK Saxony database, an anonymized population-based administrative healthcare database, which holds the complete information on outpatient health care (diagnoses according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD–10), treatment procedures according to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC–Code)) and demographic characteristics (age, sex) of 2.4 million individuals from the state of Saxony, Germany from 2005 until 2012. All individuals continuously insured until 2012 or until death were included into the present analysis (n=1.811.098).

CARDIoGRAM study

The coronary artery disease genome-wide replication and meta-analysis (CARDIoGRAM) consortium combines 14 genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for CAD with > 22.000 CAD patients and >60.000 individuals free of CAD, as previously described in detail elsewhere (Schunkert et al., 2011).

Psoriasis genetic case-control study

To investigate the association of known CAD single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and psoriasis, GWAS data from 4.489 psoriasis cases and 8.240 control subjects of European Caucasian descent recruited in Germany, UK and US were included (Ellinghaus et al., 2010; Nair et al., 2009; Strange et al., 2010).

All participating studies were approved by relevant institutional review boards, and all participants provided written or oral consent for genetic research using protocols approved by the relevant institutional body.

Epidemiological analyses

Descriptive characteristics

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of continuous variables. Non-normally distributed continuous variables are presented as median (25th, 75th percentile) and categorical variables are presented as proportions stratified by psoriasis status. Differences by psoriasis status were assessed using a Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and a Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Cross-sectional analysis

The association of psoriasis status with continuous (BMI, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol-to-HDL cholesterol ratio, carotid intima-media thickness, CRP, or leukocytes respectively) and dichotomous (hypertension, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, or angina pectoris respectively) cardiometabolic characteristics in the KORA study was analyzed using multivariable adjusted linear and logistic regression models, respectively. All models were adjusted for sex and age. Model 2 (“fully adjusted model”) additionally adjusted for smoking status (never, former, current), years of education (≤9 y, 10 y, ≥ 11 y), alcohol intake (g/d), physical activity (no activity, low activity, moderate activity, high activity), systolic blood pressure, hypertension treatment (no, yes), type 2 diabetes (no, yes), type 2 diabetes treatment (no, yes), and lipid-lowering treatment (no, yes). In sensitivity analysis, effect modification by age was investigated by inclusion of interaction terms of age and psoriasis status. All p-values were 2-sided, and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical analysis software (version 9.3).

Longitudinal analysis

For analyzing the association of psoriasis with incident cardiometabolic events in German Health Insurance beneficiaries, prevalent psoriasis in 2005 and 2006 was defined as primary exposure variable. To minimize misclassification, we defined a priori that the ICD-10-code for psoriasis (L40) had to be documented at least twice in 2005 and 2006 or once in 2005 and 2006 and at least once in 2007 until 2012. If the last documented psoriasis diagnosis was a rule-out diagnosis patients were considered as non-exposed. For cardiovascular risk factors and other potentially confounding comorbidities analogous internal validation methods were applied. Incident cardiometabolic events were identified through health insurance records. Health Insurance beneficiaries entered the study in 2005–2006 and were followed up from 2007 (start of person time) until the end of the follow-up period in 2012 (end of person time).

Outcomes of interest were incident myocardial infarction (MI) (ICD-10-code I21-I23), incident angina pectoris (ICD: I20), incident stroke (ICD: I63, I64) and incident type 2 diabetes (ICD: E11) in 2007 through 2012. Incident cases were defined as patients having no respective diagnosis documented in 2005 and 2006, and documentation of the respective ICD-10-code at least twice in 2007 until 2012. Patients with prevalent MI or type 2 diabetes in 2005/2006 were excluded. The association between prevalent psoriasis (present in 2005/2006) and new onset cardiometabolic diseases after 2006 (until 2012) was analyzed using generalized linear models using Poisson regression with robust error variances. All models were adjusted for sex and age. A second model was additionally adjusted for prevalent hypertension (ICD: I10; no, yes), type 2 diabetes (no, yes), obesity (ICD: E66; no, yes) and for disorders of lipoprotein metabolism and other lipidaemias (ICD: E78; no, yes). We attempted to deal with unmeasured disease severity by stratification by psoriasis-specific medication, i.e. data on systemic therapy (including UV therapy, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, acitretin, cyclosporine, fumaric acid, methotrexate methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, hydroxyurea) were used to further differentiate psoriasis participants into those with ‘mild’ or ‘severe’ psoriasis as reported previously (Gelfand et al., 2006). In sensitivity analysis, effect modification by age was investigated by inclusion of interaction terms of age and psoriasis status. The statistical analyses were performed with STATA data analysis and statistical software (version 12.1).

Genetic analyses

In silico analysis

A composite list of variants reported to be associated with psoriasis with genome-wide significance (P<5x10−8) was compiled using the Catalogue of Published GWAS (Hindorff et al.) and associated reference lists (Tsoi et al., 2012). A total of 57 SNPs was then evaluated for association with CAD in the CARDIoGRAM dataset (Preuss et al., 2010). In analogy, a total of 73 SNPs associated with CAD with genome-wide significance (Hindorff et al.; Lieb and Vasan, 2013) were tested for association with psoriasis in a meta-analysis of German, UK and US case-control GWAS datasets with a total of 4489 psoriasis cases and 8240 controls. Details of the meta-analysis have been previously reported (Ellinghaus et al., 2010; Nair et al., 2009). SNPTEST was used to associate the imputed dosage for each SNP with psoriasis status separately in each study sample with adjustment for the first three principal components from a multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis of population stratification. The association test results of those SNPs with relatively high confidence (PROPER_Info>0.4) were then meta-analyzed with METAL using the inverse-variance method based on a fixed-effect model. We had at least 96% power to detect an OR≥1.2 for a SNP with ≥10% allele frequency applying a lenient significance threshold of P<0.01 as proposed by Ellinghaus et al. (Ellinghaus et al., 2012).

Proportion of psoriasis risk SNPs with a positive association with CAD and vice versa

We assessed the proportion of psoriasis risk-increasing alleles with a positive association with CAD (OR >1) and vice versa. We tested whether this proportions differed from 0.5 (proportion of SNPs with an OR>1 for CAD by chance) using an exact binomial test as proposed elsewhere (Lieb et al., 2013).

Metabochip study

927 German psoriasis patients and 3.713 controls were genotyped using the Metabochip®, a custom Illumina iSelect genotyping array of nearly 200,000 SNP markers, which was designed to analyze and finemap association signals identified through GWAS meta-analyses of cardiometabolic traits and to fine-map established loci (Voight et al., 2012). The patients were recruited from tertiary dermatology clinics based at the Technische Universität Munich and the University of Kiel (Ellinghaus et al., 2012); controls were derived from the population-based KORA and POPGEN studies (Holle et al., 2005; Krawczak et al., 2006).

The genotyping and calling of the Metabochip were performed using the Illumina GenomeStudio software. Genotype data of all subsamples underwent the same basic quality control as detailed in the online supplement. After quality control procedure, 99,362 SNPs were analyzed. Within the cleaned Metabochip dataset, we performed 2 sets of analyses: First, we related all 99,362 SNPs to psoriasis using a logistic regression model, adjusting for sex and the first eight principal components from the MDS of population stratification. Second, we looked in detail at regions that have been previously reported to be associated with Psoriasis. From these regions, only 4 lead SNPs were directly genotyped on the Metabochip. For the remaining previously reported psoriasis regions, we investigated the surrounding regions (+/−500kb) of each previously reported psoriasis lead SNP and report the SNP with the lowest p-value. All association analyses were performed in PLINK (Purcell et al., 2007). We applied a suggestive and array-wide significance level of P = 5x10−6 and P = 5.03x10−7, respectively. We had >79% power to detect an OR≥1.25 for a SNP assuming the allele frequency is ≥10% at the 5x10−6 significance level.

Online Repository

methods

KORA sample

In the MONICA/KORA surveys, data on sex, age, smoking habit, educational attainment, alcohol intake, physical activity, medical history and medication use was assessed during a standardized face-to-face computer assisted personal interview by trained study personnel.

Participants were asked to report the amount of beer, wine, and spirits consumed on the previous workday and previous weekend. The alcohol intake (in g/day) was obtained from this information as previously published (Wellmann et al., 2004). Participants were asked to provide the time per week spent engaging in sports in summer and winter seasons using the four response options ‘none’, ‘<1 h/week’, ‘1-2 h/week’, ‘>2 h/week’ (Ziegler et al., 2008). All participants underwent a medical examination by trained medical staff, which comprised anthropometrical, and blood pressure measurements according to standardized protocols previously published (Rathmann et al., 2003). BMI (in kg/m2) was calculated as weight divided by height squared. The diagnosis of psoriasis was based on a reported physician’s diagnosis ever (KORA C), and a dermatological skin examination at the time of follow-up (KORA F4). Venous blood samples were drawn from all subjects. Plasma CRP concentrations were measured using a high-sensitive immuneradiometric assay (range, 0.05– 10 mg/l). White blood cell count was determined from fresh samples (Coulter counter STKS). Total cholesterol was determined by cholesterol esterase method (CHOL Flex, Dade-Behring, CHOD-PAP method), HDL-cholesterol was measured using the AHDL Flex (Dade-Behring, CHOD-PAP method after selective release of HDL) and triglycerides were measured using a TGL Flex (Dade Behring, enzymatic colorimetric test, GPO-PAP method). HsCRP was measured by particle enhanced immunonephelometry using a BN II (Fa. Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products, Marburg, Germany; level of detection 0.16 mg/L). Blood glucose was analysed using a hexokinase method (Gluco-quant;Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). In participants of the F4 study, lipids were measured using the Dimension RxL (Dade Behring) (van Vliet-Ostaptchouk et al, 2014). In participants of the F4 study, the thickness of the carotid intima-media and ankle-brachial index were assessed according to methods previously published (Kowall et al., 2012; Stöckl et al., 2013). Measurements of the right and left common carotid artery thickness were averaged to obtain the overall common carotid artery thickness. Peripheral arterial disease was defined by an ankle-brachial index <0.9 and/or the self-reported presence of claudication, assessed by the Edinburgh questionnaire (Stöckl et al, 2013).

Variable categorization

The years of education were categorized as follows: ≤9 y (secondary general school-leaving certificate), 10 y (intermediate school-leaving certificate), or ≥ 11 y (university of applied sciences or university entrance qualification). Physical activity was categorized as follows: no activity (no sports in summer or winter season), low activity (engaging in sports <1 h/week in summer or winter season), moderate activity (engaging in sports 1 – 2 h/week regularly in summer or winter season), high activity (engaging in sports >2 h/week in summer and winter season). Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure as ≥90 mmHg or antihypertensive treatment. In participants of the F4 study, which provided fasting blood samples, the metabolic syndrome was defined as published by Alberti et al. (Alberti et al, 2009).

Test of association of variants in cardiometabolic candidate genes with psoriasis (Metabochip analysis)

The test of association of variants in cardiometabolic candidate genes with psoriasis was executed with PLINK (Purcell et al, 2007) and R . Monomorphous SNPs, SNPs with a callrate<0.98, a minor allele frequency<5% and p-value of deviation from Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium <10−6 were removed. Furthermore, individuals with very low call rate (<50%), duplicates, close relatedness (below 2nd to 3rd degree) as well as population outliers (n=6) from the MDS analysis were excluded: Finally, a total of 936 psoriasis cases (56.6% female, mean age 50.0 years, mean BMI 27.57 kg/m2) and 3713 controls (50.2% female, mean age 55.7 years, mean BMI 27.20 kg/m2) and 99.362 SNPs were analyzed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments and Funding

We thank all individuals with psoriasis and CAD, their families, control individuals and clinicians for their participation. The KORA study was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München—German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and by the State of Bavaria. The project received infrastructure support through the DFG Clusters of Excellence “Inflammation at Interfaces” (grants EXC306 and EXC306/2), and was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the framework of the e:Med research and funding concept (e:AtheroSysMed and sysINFLAME, grant # 01ZX1306A) and the PopGen 2.0 network (01EY1103). Support for the case-control psoriasis sample used for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R01AR042742, R01AR050511, R01AR054966, R01AR062382, R01AR065183 to JTE). JTE is supported by the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Hospital. This study makes use of data generated by the CARDIoGRAM Consortium and the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium. Members of the consortia are listed in the Data Supplement. A full list of the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium investigators who contributed to the generation of the data is available from www.wtccc.org.uk.wtccc.org.uk. Funding for the project was provided by the Wellcome Trust under award 076113 and 085475. We also acknowledge support from the Department of Health via the NIHR BioResource Clinical Research Facility and comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The funders had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations

- AP

angina pectoris

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CARDIoGRAM

coronary artery disease genome-wide replication and meta-analysis

- CVD

cardiovascular diseases

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- ICD

International Statistical Classification of Diseases

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MDS

multidimensional scaling

- PAD

peripheral arterial disease

- SNPs

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

Appendix

CARDIoGRAM Consortium members

Executive Committee:

Sekar Kathiresan1,2,3, Muredach P. Reilly4, Nilesh J. Samani5,6, Heribert Schunkert7

Executive Secretary:

Jeanette Erdmann7

Steering Committee:

Themistocles L. Assimes8, Eric Boerwinkle9, Jeanette Erdmann7, Alistair Hall10, Christian Hengstenberg11, Sekar Kathiresan1,2,3, Inke R. König12, Reijo Laaksonen13, Ruth McPherson14, Muredach P. Reilly4, Nilesh J. Samani5,6, Heribert Schunkert7, John R. Thompson15, Unnur Thorsteinsdottir16,17, Andreas Ziegler12

Statisticians:

Inke R. König12 (chair), John R. Thompson15 (chair), Devin Absher18, Li Chen19, L. Adrienne Cupples20,21, Eran Halperin22, Mingyao Li23, Kiran Musunuru1,2,3, Michael Preuss12,7, Arne Schillert12, Gudmar Thorleifsson16, Benjamin F. Voight2,3,24, George A. Wells25

Writing group:

Themistocles L. Assimes8, Panos Deloukas26, Jeanette Erdmann7, Hilma Holm16, Sekar Kathiresan1,2,3, Inke R. König12, Ruth McPherson14, Muredach P. Reilly4, Robert Roberts14, Nilesh J. Samani5,6, Heribert Schunkert7, Alexandre F. R. Stewart14

ADVANCE:

Devin Absher18, Themistocles L. Assimes8, Stephen Fortmann8, Alan Go27, Mark Hlatky8, Carlos Iribarren27, Joshua Knowles8, Richard Myers18, Thomas Quertermous8, Steven Sidney27, Neil Risch28, Hua Tang29

CADomics:

Stefan Blankenberg30, Tanja Zeller30, Arne Schillert12, Philipp Wild30, Andreas Ziegler12, Renate Schnabel30, Christoph Sinning30, Karl Lackner31, Laurence Tiret32, Viviane Nicaud32, Francois Cambien32, Christoph Bickel30, Hans J. Rupprecht30, Claire Perret32, Carole Proust32, Thomas Münzel30

CHARGE:

Maja Barbalic33, Joshua Bis34, Eric Boerwinkle9, Ida Yii-Der Chen35, L. Adrienne Cupples20,21, Abbas Dehghan36, Serkalem Demissie-Banjaw37,21, Aaron Folsom38, Nicole Glazer39, Vilmundur Gudnason40,41, Tamara Harris42, Susan Heckbert43, Daniel Levy21, Thomas Lumley44, Kristin Marciante45, Alanna Morrison46, Christopher J. O´Donnell47, Bruce M. Psaty48, Kenneth Rice49, Jerome I. Rotter35, David S. Siscovick50, Nicholas Smith43, Albert Smith40,41, Kent D. Taylor35, Cornelia van Duijn36, Kelly Volcik46, Jaqueline Whitteman36, Vasan Ramachandran51, Albert Hofman36, Andre Uitterlinden52,36

deCODE:

Solveig Gretarsdottir16, Jeffrey R. Gulcher16, Hilma Holm16, Augustine Kong16, Kari Stefansson16,17, Gudmundur Thorgeirsson53,17, Karl Andersen53,17, Gudmar Thorleifsson16, Unnur Thorsteinsdottir16,17

GERMIFS I and II:

Jeanette Erdmann7, Marcus Fischer11, Anika Grosshennig12,7, Christian Hengstenberg11, Inke R. König12, Wolfgang Lieb54, Patrick Linsel-Nitschke7, Michael Preuss12,7, Klaus Stark11, Stefan Schreiber55, H.-Erich Wichmann56,58,59, Andreas Ziegler12, Heribert Schunkert7

GERMIFS III (KORA):

Zouhair Aherrahrou7, Petra Bruse7, Angela Doering56, Jeanette Erdmann7, Christian Hengstenberg11, Thomas Illig56, Norman Klopp56, Inke R. König12, Patrick Linsel-Nitschke7, Christina Loley12,7, Anja Medack7, Christina Meisinger56, Thomas Meitinger57,60, Janja Nahrstedt12,7, Annette Peters56, Michael Preuss12,7, Klaus Stark11, Arnika K. Wagner7, H.Erich Wichmann56,58,59, Christina Willenborg12,7, Andreas Ziegler12, Heribert Schunkert7

LURIC/AtheroRemo:

Bernhard O. Böhm61, Harald Dobnig62, Tanja B. Grammer63, Eran Halperin22, Michael M. Hoffmann64, Marcus Kleber65, Reijo Laaksonen13, Winfried März63,66,67, Andreas Meinitzer66, Bernhard R. Winkelmann68, Stefan Pilz62, Wilfried Renner66, Hubert Scharnagl66, Tatjana Stojakovic66, Andreas Tomaschitz62, Karl Winkler64

MIGen:

Benjamin F. Voight2,3,24, Kiran Musunuru1,2,3, Candace Guiducci3, Noel Burtt3, Stacey B. Gabriel3, David S. Siscovick50, Christopher J. O’Donnell47, Roberto Elosua69, Leena Peltonen49, Veikko Salomaa70, Stephen M. Schwartz50, Olle Melander26, David Altshuler71,3, Sekar Kathiresan1,2,3

OHGS:

Alexandre F. R. Stewart14, Li Chen19, Sonny Dandona14, George A. Wells25, Olga Jarinova14, Ruth McPherson14, Robert Roberts14

PennCATH/MedStar:

Muredach P. Reilly4, Mingyao Li23, Liming Qu23, Robert Wilensky4, William Matthai4, Hakon H. Hakonarson72, Joe Devaney73, Mary Susan Burnett73, Augusto D. Pichard73, Kenneth M. Kent73, Lowell Satler73, Joseph M. Lindsay73, Ron Waksman73, Christopher W. Knouff74, Dawn M. Waterworth74, Max C. Walker74, Vincent Mooser74, Stephen E. Epstein73, Daniel J. Rader75,4

WTCCC:

Nilesh J. Samani5,6, John R. Thompson15, Peter S. Braund5, Christopher P. Nelson5, Benjamin J. Wright76, Anthony J. Balmforth77, Stephen G. Ball78, Alistair S. Hall10, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium

Affiliations

1Cardiovascular Research Center and Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; 2Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; 3Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, MA, USA; 4The Cardiovascular Institute, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 5Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK; 6Leicester National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Unit in Cardiovascular Disease, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, LE3 9QP, UK; 7Medizinische Klinik II, Universität zu Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany; 8Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA; 9University of Texas Health Science Center, Human Genetics Center and Institute of Molecular Medicine, Houston, TX, USA; 10Division of Cardiovascular and Neuronal Remodelling, Multidisciplinary Cardiovascular Research Centre, Leeds Institute of Genetics, Health and Therapeutics, University of Leeds, UK; 11Klinik und Poliklinik für Innere Medizin II, Universität Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany; 12Institut für Medizinische Biometrie und Statistik, Universität zu Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany; 13Science Center, Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland; 14The John & Jennifer Ruddy Canadian Cardiovascular Genetics Centre, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, Ottawa, Canada; 15Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK; 16deCODE Genetics, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland; 17University of Iceland, Faculty of Medicine, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland; 18Hudson Alpha Institute, Huntsville, Alabama, USA; 19Cardiovascular Research Methods Centre, University of Ottawa Heart Institute, 40 Ruskin Street, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1Y 4W7; 20Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA USA; 21National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, MA, USA; 22The Blavatnik School of Computer Science and the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel, and the International Computer Science Institute, Berkeley, CA, USA; 23Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 24Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; 25Research Methods, Univ Ottawa Heart Inst; 26Department of Clinical Sciences, Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases, Scania University Hospital, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden; 27Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente, Oakland, CA, USA; 28Institute for Human Genetics, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA; 29Dept Cardiovascular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic; 30Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik, Johannes-Gutenberg Universität Mainz, Universitätsmedizin, Mainz, Germany; 31Institut für Klinische Chemie und Laboratoriumsmediizin, Johannes-Gutenberg Universität Mainz, Universitätsmedizin, Mainz, Germany; 32INSERM UMRS 937, Pierre and Marie Curie University (UPMC, Paris 6) and Medical School, Paris, France; 33University of Texas Health Science Center, Human Genetics Center, Houston, TX, USA; 34Cardiovascular Health Resarch Unit and Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA USA; 35Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Medical Genetics Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 36Erasmus Medical Center, Department of Epidemiology, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; 37Boston University, School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; 38University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health (A.R.F.), Minneapolis, MN, USA; 39University of Washington, Cardiovascular Health Research Unit and Department of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA; 40Icelandic Heart Association, Kopavogur Iceland; 41University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland; 42Laboratory of Epidemiology, Demography, and Biometry, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD, USA; 43University of Washington, Department of Epidemiology, Seattle, WA, USA; 44University of Washington, Department of Biostatistics, Seattle, WA, USA; 45University of Washington, Department of Internal Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA; 46University of Texas, School of Public Health, Houston, TX, USA; 47National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, MA and Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; 48Center for Health Studies, Group Health, Departments of Medicine, Epidemiology, and Health Services, Seattle, WA, USA; 49The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, The Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, UK; 50Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, Departments of Medicine and Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle; 51Boston University Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA; 52Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; 53Department of Medicine, Landspitali University Hospital, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland; 54Boston University School of Medicine, Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, MA, USA; 55Institut für Klinische Molekularbiologie, Christian-Albrechts Universität, Kiel, Germany; 56Institute of Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany; 57Institut für Humangenetik, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Deutsches Forschungszentrum für Umwelt und Gesundheit, Neuherberg, Germany; 58Institute of Medical Information Science, Biometry and Epidemiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany; 59Klinikum Grosshadern, Munich, Germany; 60Institut für Humangenetik, Technische Universität München, Germany; 61Division of Endocrinology and Diabetes, Graduate School of Molecular Endocrinology and Diabetes, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany; 62Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, Medical University of Graz, Austria; 63Synlab Center of Laboratory Diagnostics Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany; 64Division of Clinical Chemistry, Department of Medicine, Albert Ludwigs University, Freiburg, Germany; 65LURIC non profit LLC, Freiburg, Germany; 66Clinical Institute of Medical and Chemical Laboratory Diagnostics, Medical University Graz, Austria; 67Institute of Public Health, Social and Preventive Medicine, Medical Faculty Manneim, University of Heidelberg, Germany; 68Cardiology Group Frankfurt-Sachsenhausen, Frankfurt, Germany; 69Cardiovascular Epidemiology and Genetics Group, Institut Municipal d’Investigació Mèdica, Barcelona; Ciber Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERSP), Spain; 70Chronic Disease Epidemiology and Prevention Unit, Department of Chronic Disease Prevention, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland; 71Department of Molecular Biology and Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA; 72The Center for Applied Genomics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; 73Cardiovascular Research Institute, Medstar Health Research Institute, Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC 20010, USA; 74Genetics Division and Drug Discovery, GlaxoSmithKline, King of Prussia, Pennsylvania 19406, USA; 75The Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 76Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK; 77Division of Cardiovascular and Diabetes Research, Multidisciplinary Cardiovascular Research Centre, Leeds Institute of Genetics, Health and Therapeutics, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK; 78LIGHT Research Institute, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortia 2 members

Management Committee

Peter Donnelly (Chair)1,2, Ines Barroso (Deputy Chair)3, Jenefer M Blackwell4,5, Elvira Bramon6 , Matthew A Brown7 , Juan P Casas8 , Aiden Corvin9, Panos Deloukas3, Audrey Duncanson10, Janusz Jankowski11, Hugh S Markus12, Christopher G Mathew13, Colin NA Palmer14, Robert Plomin15, Anna Rautanen1, Stephen J Sawcer16, Richard C Trembath13, Ananth C Viswanathan17, Nicholas W Wood18

Data and Analysis Group

Chris C A Spencer1, Gavin Band1, Céline Bellenguez1, Colin Freeman1, Garrett Hellenthal1, Eleni Giannoulatou1, Matti Pirinen1, Richard Pearson1, Amy Strange1, Zhan Su1, Damjan Vukcevic1, Peter Donnelly1,2

DNA, Genotyping, Data QC and Informatics Group

Cordelia Langford3, Sarah E Hunt3, Sarah Edkins3, Rhian Gwilliam3, Hannah Blackburn3, Suzannah J Bumpstead3, Serge Dronov3, Matthew Gillman3, Emma Gray3, Naomi Hammond3, Alagurevathi Jayakumar3, Owen T McCann3, Jennifer Liddle3, Simon C Potter3, Radhi Ravindrarajah3, Michelle Ricketts3, Matthew Waller3, Paul Weston3, Sara Widaa3, Pamela Whittaker3, Ines Barroso3, Panos Deloukas3.

Publications Committee

Christopher G Mathew (Chair)13, Jenefer M Blackwell4,5, Matthew A Brown7, Aiden Corvin9, Mark I McCarthy19, Chris C A Spencer1 1Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, Roosevelt Drive, Oxford OX3 7LJ, UK; 2Dept Statistics, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3TG, UK; 3Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK; 4Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, Centre for Child Health Research, University of Western Australia, 100 Roberts Road, Subiaco, Western Australia 6008; 5Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, Cambridge CB2 0XY, UK; 6Department of Psychosis Studies, NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London and The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, Denmark Hill, London SE5 8AF, UK; 7Diamantina Institute of Cancer, Immunology and Metabolic Medicine, Princess Alexandra Hospital, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; 8Dept Epidemiology and Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London WC1E 7HT and Dept Epidemiology and Public Health, University College London WC1E 6BT, UK; 9Neuropsychiatric Genetics Research Group, Institute of Molecular Medicine, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Eire; 10Molecular and Physiological Sciences, The Wellcome Trust, London NW1 2BE; 11Centre for Digestive Diseases, Queen Mary University of London, London E1 2AD, UK and Digestive Diseases Centre, Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester LE7 7HH, UK and Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Old Road Campus, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 7DQ, UK; 12Clinical Neurosciences, St George’s University of London, London SW17 0RE; 13King’s College London Dept Medical and Molecular Genetics, School of Medicine, Guy’s Hospital, London SE1 9RT, UK; 14Biomedical Research Centre, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, Dundee DD1 9SY, UK; 15King’s College London Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, Denmark Hill, London SE5 8AF, UK; 16University of Cambridge Dept Clinical Neurosciences, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK; 17NIHR Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology, Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, London EC1V 2PD, UK; 18Dept Molecular Neuroscience, Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG, UK; 19Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism (ICDEM), Churchill Hospital, Oxford OX3 7LJ, UK.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

JTE reports grants from National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study. JSch reports grants from MSD, grants from Wyeth, grants from Novartis, personal fees from Genentech, outside the submitted work. SW reports grants from German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, during the conduct of the study; grants from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Biogen, grants and personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Roche-Posay, outside the submitted work. HS reports grants from e:AtherosSysMed, grants from DZHK/MHA, grants from CVgenes@target, personal fees from AstraZeneca Germany, personal fees from AstraZeneca India, personal fees from SERVIER GmbH Germany, personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim Germany, personal fees from MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH Germany, personal fees from AMGEN GmbH Germany, personal fees from BERLIN-CHEMIE AG Germany, outside the submitted work.

References

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013;68:654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy RM, Marion MC, Kaufman KM, et al. Identification of candidate loci at 6p21 and 21q22 in a genome-wide association study of cardiac manifestations of neonatal lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3415–3424. doi: 10.1002/art.27658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies RW, Wells GA, Stewart AF, et al. A genome-wide association study for coronary artery disease identifies a novel susceptibility locus in the major histocompatibility complex. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2012;5:217–225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlatshahi EA, Kavousi M, Nijsten T, et al. Psoriasis is not associated with atherosclerosis and incident cardiovascular events: the Rotterdam Study. J Invest Dermatol. 2013a;133:2347–2354. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlatshahi EA, van der Voort EA, Arends LR, et al. Markers of systemic inflammation in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The British journal of dermatology. 2013b;169:266–282. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinghaus D, Ellinghaus E, Nair RP, et al. Combined analysis of genome-wide association studies for Crohn disease and psoriasis identifies seven shared susceptibility loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:636–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinghaus E, Ellinghaus D, Stuart PE, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a psoriasis susceptibility locus at TRAF3IP2. Nat Genet. 2010;42:991–995. doi: 10.1038/ng.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng BJ, Sun LD, Soltani-Arabshahi R, et al. Multiple Loci within the major histocompatibility complex confer risk of psoriasis. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735–1741. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindorff L, MacArthur J, Morales J, et al. [Accessed December 2013];A Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies. < www.genome.gov/gwastudies> Accessed.

- Holle R, Happich M, Lowel H, et al. KORA--a research platform for population based health research. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S19–S25. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Birlea SA, Fain PR, et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies a quantitative trait locus in the MHC class II region associated with generalized vitiligo age of onset. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball AB, Wu Y. Cardiovascular disease and classic cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1147–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight J, Spain SL, Capon F, et al. Conditional analysis identifies three novel major histocompatibility complex loci associated with psoriasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:5185–5192. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczak M, Nikolaus S, von Eberstein H, et al. PopGen: population-based recruitment of patients and controls for the analysis of complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Community Genet. 2006;9:55–61. doi: 10.1159/000090694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahoute C, Herbin O, Mallat Z, et al. Adaptive immunity in atherosclerosis: mechanisms and future therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:348–358. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langan SM, Seminara NM, Shin DB, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:556–562. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Han J, Hu FB, et al. Psoriasis and risk of type 2 diabetes among women and men in the United States: a population-based cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:291–298. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb W, Jansen H, Loley C, et al. Genetic predisposition to higher blood pressure increases coronary artery disease risk. Hypertension. 2013;61:995–1001. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb W, Vasan RS. Genetics of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2013;128:1131–1138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419–424. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Wang L, Chen S, et al. Genome-wide association study in Han Chinese identifies four new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nature genetics. 2012;44:890–894. doi: 10.1038/ng.2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Chen H, Nikamo P, et al. Association of cardiovascular and metabolic disease genes with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:836–839. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ, et al. The association between psoriasis and dyslipidaemia: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:486–495. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IM, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, et al. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:1014–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muggah E, Graves E, Bennett C, et al. Ascertainment of chronic diseases using population health data: a comparison of health administrative data and patient self-report. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair RP, Duffin KC, Helms C, et al. Genome-wide scan reveals association of psoriasis with IL-23 and NF-kappaB pathways. Nat Genet. 2009;41:199–204. doi: 10.1038/ng.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijsten T, Wakkee M. Complexity of the association between psoriasis and comorbidities. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1601–1603. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss M, Konig IR, Thompson JR, et al. Design of the Coronary ARtery DIsease Genome-Wide Replication And Meta-Analysis (CARDIoGRAM) Study: A Genome-wide association meta-analysis involving more than 22 000 cases and 60 000 controls. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:475–483. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.899443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarasekera EJ, Neilson JM, Warren RB, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular disease in individuals with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:2340–2346. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer I, Rustenbach SJ, Radtke M, et al. [Epidemiology of psoriasis in Germany--analysis of secondary health insurance data] Gesundheitswesen. 2011;73:308–313. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1252022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–338. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaharyar S, Warraich H, McEvoy JW, et al. Subclinical cardiovascular disease in plaque psoriasis: Association or causal link? Atherosclerosis. 2014;232:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DH, Massarotti E, Garg R, et al. Association between disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and diabetes risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. JAMA. 2011;305:2525–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern RS, Nijsten T. Going beyond associative studies of psoriasis and cardiovascular disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:499–501. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange A, Capon F, Spencer CC, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies new psoriasis susceptibility loci and an interaction between HLA-C and ERAP1. Nat Genet. 2010;42:985–990. doi: 10.1038/ng.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Farinas M, Li K, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Expanding the psoriasis disease profile: interrogation of the skin and serum of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2552–2564. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swart E, Stallmann C, Powietzka J, et al. [Data linkage of primary and secondary data: a gain for small-area health-care analysis?] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2014;57:180–187. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Knight J, et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1341–1348. doi: 10.1038/ng.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, et al. Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet. 2005;37:357–364. doi: 10.1038/ng1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight BF, Kang HM, Ding J, et al. The metabochip, a custom genotyping array for genetic studies of metabolic, cardiovascular, and anthropometric traits. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Gao H, Loyd CM, et al. Chronic skin-specific inflammation promotes vascular inflammation and thrombosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2067–2075. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung H, Takeshita J, Mehta NN, et al. Psoriasis severity and the prevalence of major medical comorbidity: a population-based study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1173–1179. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhernakova A, Withoff S, Wijmenga C. Clinical implications of shared genetics and pathogenesis in autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:646–659. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capon F, Bijlmakers MJ, Wolf N, et al. Identification of ZNF313/RNF114 as a novel psoriasis susceptibility gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1938–1945. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economou M, Pappas G. New global map of Crohn's disease: Genetic, environmental, and socioeconomic correlations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:709–720. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinghaus D, Ellinghaus E, Nair RP, et al. Combined analysis of genome-wide association studies for Crohn disease and psoriasis identifies seven shared susceptibility loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:636–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinghaus E, Ellinghaus D, Stuart PE, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a psoriasis susceptibility locus at TRAF3IP2. Nat Genet. 2010;42:991–995. doi: 10.1038/ng.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowall B, Ebert N, Then C, et al. Associations between blood glucose and carotid intima-media thickness disappear after adjustment for shared risk factors: the KORA F4 study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Helms C, Liao W, et al. A genome-wide association study of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis identifies new disease loci. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair RP, Duffin KC, Helms C, et al. Genome-wide scan reveals association of psoriasis with IL-23 and NF-kappaB pathways. Nat Genet. 2009;41:199–204. doi: 10.1038/ng.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann W, Haastert B, Icks A, et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in Southern Germany: target populations for efficient screening. The KORA survey 2000. Diabetologia. 2003;46:182–189. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-1025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]