Abstract

The purpose of this research was to examine age, sex, and racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment in childhood in a nationally representative sample of the United States. Data were from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) collected in 2004 and 2005 (n = 34,653). Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine age, sex, and racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment. Results suggest that the prevalence of harsh physical punishment has been decreasing among more recently born age groups; however, there appear to be sex and racial differences in this trend over time. The magnitude of the decrease appears to be stronger for males than for females. By race, the decrease in harsh physical punishment over time is only apparent among Whites; Black participants demonstrate little change over time, and harsh physical punishment seems to be increasing over time among Hispanics. Prevention and intervention efforts that educate about the links of physical punishment to negative outcomes and alternative non-physical discipline strategies may be particularly useful in reducing the prevalence of harsh physical punishment over time.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, Harsh physical punishment, Cohort effects, Age effects, Racial/ethnic differences, Sex differences

Introduction

Controversy exists with regard to the use of physical punishment in childrearing. Advocates assert that physical punishment is not harmful provided it is implemented in a calm and controlled manner for corrective purposes within the context of a warm and supportive parent–child relationship (Baumrind, 1997). Opponents of physical punishment have argued that physical punishment not only violates children’s basic human rights (Durrant, 2008), but also that research consistently indicates that physical punishment is associated with adverse mental health, physical health, developmental and behavioral outcomes across the lifespan (Afifi, Brownridge, Cox, & Sareen, 2006; Afifi et al., 2014; Afifi, Mota, Dasiewicz, MacMillan, & Sareen, 2012; Afifi, Mota, MacMillan, & Sareen, 2013; Douglas & Straus, 2006; Durrant & Ensom, 2012; Gershoff, 2002). As a consequence, a number of key health organizations have issued position statements advocating against the use of physical punishment in childrearing (Canadian Paediatric Association, 2004; Canadian Psychological Association, 2004; Shelov & Altman, 2009; Smith, 2012).

Physical punishment is defined as “the use of physical force with the intention of causing the child to experience bodily pain or discomfort so as to correct or punish the child’s behavior” (Gershoff, 2008, p. 9). While spanking is most often defined as hitting a child’s buttocks with an open hand (Gershoff, 2013), physical punishment is a broader concept that can include spanking and other forms of mild, physical force such as a slap on a child’s hand, as well as more severe forms of physical force such as hitting a child with an object or slapping a child across the face (Gershoff, 2008). A variety of different definitions and measures of physically aggressive parenting practices have been used throughout the literature, making comparisons between studies difficult (Douglas & Straus, 2006). In this study, we chose to use the term harsh physical punishment rather than physical punishment due to the recognition that our measure (i.e., pushed, grabbed, shoved, or hit by a parent or other adult living in your home) could include acts beyond the range of customary or more normative disciplinary actions such as spanking (Afifi et al., 2012).

There is some debate in the literature as to what is considered abusive vs. non-abusive disciplinary practices (Whipple & Richey, 1997). Generally, physically aggressive disciplinary practices that pose a high risk of injury to the child (or cause actual harm or injury to the child) are the practices where social and legal interventions are applied (Straus, 2001). In this study, we attempted to assess differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment, independent of physical harm (i.e., being hit so hard that it left marks, bruises, or caused an injury), because this type of punishment is often used in childrearing (Afifi et al., 2014; Hanson et al., 2006; Hawkins et al., 2010; Straus & Stewart, 1999), but is unlikely to result in legal or social service intervention (Straus, 2001). A major limitation of extant research on physical punishment (including spanking) is that concurrent, physically abusive experiences are not considered in most analyses (Baumrind, Larzelere, & Cowan, 2002).

Nationally representative data from the United States has indicated that the physical punishment of children is nearly a universal phenomenon, with 94% of toddlers being physically punished (usually by spanking or being slapped on the hand) by parents in the past year (Straus & Stewart, 1999). It is noteworthy that more severe forms of physical punishment are frequently used in childrearing. For example, Straus and Stewart (1999) also reported that more than 1 in 4 parents reported hitting children aged 5–12 years with objects and between 4.8% and 6.9% of children aged 2–17 years were slapped on the face, head, or ears. Similarly, nationally representative data from Canada has indicated that 22.3% of the adult Canadian population reported having been slapped on the face, head, or ears, or spanked or hit with something hard, and 10.5% reported having been pushed, grabbed, shoved, or had something thrown at them before the age of 16 years (Afifi et al., 2014). Data from the 1995 National Survey of Adolescents (NSA) and the 2005 National Survey of Adolescents-Replication (NSA-R) conducted in the United States found that 9.0% (NSA) and 8.5% (NSA-R) of adolescents aged 12–17 years experienced injurious spanking (i.e., spanked so hard it caused bad bruises, cuts, or welts); 4.2% (NSA-R) reported having ever been thrown across the room or against a wall, floor, car, or against other hard surfaces by a parent or other adult in charge of them (Hawkins et al., 2010); and approximately 10% (NSA) experienced severe physical assault by a caretaker (Hanson et al., 2006). These findings highlight that the experience of harsher forms of physical punishment are not an uncommon experience for many children and youth.

Attitudes toward the use of physical punishment in childrearing have also been shifting in recent decades (Durrant, 2008; Gershoff, 2008; Zolotor & Puzia, 2010). Where physical punishment in childrearing was once considered a necessary and integral component of the disciplinary process (Straus, 2001), evidence gleaned from different cross-sectional surveys conducted in the United States points to a decline in attitudes favoring physical punishment in childrearing (Straus, 2010). In the United States, there appears to be substantial support that spanking a child with a hand represents a non-abusive parenting practice, less consensus exists with regard to more moderate and severe forms of physical punishment such as slapping a child on the face or the use of implements for disciplinary purposes (Bensley et al., 2004). At the international level, 39 nations have now implemented bans on the use of physical punishment against children (Global Initiative to End all Corporal Punishment of Children, 2014). The intention of such bans are not to place parents in jails for spanking, but rather to protect the basic human rights of children and to make societal shifts toward no tolerance for violence against children. Additionally, the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) explicitly prohibits the use of any form of physical or mental violence against children. Taken together, evidence suggests a global trend in attitudinal change regarding the acceptability of physical punishment as a legitimate and effective parental disciplinary technique. Nonetheless, physical punishment in childrearing remains a legal practice in the United States, Canada, and elsewhere.

Less information exists regarding whether these shifting attitudes have translated into a decreased use of physical punishment by parents over time. In the United States, evidence suggests an 18% decrease in the use of physical punishment (spanking or slapping) over the period 1975 to 2002 (Zolotor, Theodore, Runyan, Chang, & Laskey, 2011). Substantiated cases of physical abuse have declined 43% over the period from 1992 to 2004 (Finkelhor & Jones, 2006). Data from the Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4) has also indicated a 23% decline in rates of physical abuse based on the harm standard since 1993 (Sedlak et al., 2010). However, data from the NSA and NSA-R indicates no significant change in the overall prevalence of injurious spanking from 1995 to 2005 (Hawkins et al., 2010). Further, little is known about the prevalence of harsh physical punishment independent of other forms of maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, and exposure to intimate partner violence) of children in the United States born prior to 1975.

Both sex and racial differences in the prevalence of physical punishment have been reported in the literature. Some research finds that males are more likely to experience harsh physical punishment than females (Afifi et al., 2014; Dietz, 2000; Douglas & Straus, 2006) whereas other studies report no significant gender difference (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005; Hanson et al., 2006; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006). It remains unclear whether gender differences in the prevalence of non-injurious, but more severe forms of physical punishment exist. Most research finds that African American children are more likely to experience harsh physical punishment than White children (Berlin et al., 2009; Finkelhor et al., 2005; Gershoff, Lansford, Sexton, Davis-Kean, & Sameroff, 2012; Hanson et al., 2006; Hawkins et al., 2010; Lorber, O’Leary, & Smith Slep, 2011; MacKenzie, Nicklas, Brooks-Gunn, & Waldfogel, 2011; Turner et al., 2006). Differences in findings may be due to the substantial within group diversity. For example, less acculturated Mexican American (Berlin et al., 2009) and foreign-born Hispanic (MacKenzie et al., 2011) parents were less likely to spank in the past week than White parents, but more acculturated Mexican American and American-born Hispanic parents evidenced similar rates of past week spanking as White parents (Berlin et al., 2009; MacKenzie et al., 2011). Interestingly, data from the NSA and NSA-R found that both White (7.7%) and Hispanic (8.0%) adolescents reported significantly lower injurious spanking than Black (14.9%) adolescents in 1995, but both Black (11.4%) and Hispanic (11.3%) adolescents reported significantly higher rates than White (7.4%) adolescents in 2005 (Hawkins et al., 2010). Similarly, data from the NIS-4 indicated that the rate of decline of physical abuse since 1993 was substantially greater for White children (38%) compared to both Black (15%) and Hispanic (8%) children (Sedlak et al., 2010). These findings suggest that changes in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment may not be the same for all racial and ethnic groups. The confounding of race with socioeconomic status in many studies makes conclusions regarding racial variations in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment difficult. As well, longer term trends in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment by sex and race remain unknown.

Therefore, the overall purpose of the current study was to examine age, sex, and racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment in a nationally representative sample of the United States. The specific research objectives were to examine: (a) the distribution of harsh physical punishment by sociodemographic variables, (b) the prevalence of harsh physical punishment across different age cohorts, (c) sex differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment between and within different age cohorts, and (d) racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment between and within different age cohorts.

Methods

Sample

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is a representative sample of civilian, non-institutionalized adults living in the United States. The sampling frame (i.e., households) was based on the U.S. Bureau of the Census Supplementary Survey, which also included a group quarters’ (i.e., military living off base, rooming houses, boarding houses, facilities for housing workers, college quarters, and group homes) sampling frame (Grant et al., 2004). Primary sampling units were randomly selected from the sampling frame, and one person from each household or group quarters was randomly selected for interview (Grant et al., 2004). Data were collected through face-to-face interviews by trained lay interviewers of the U.S. Census Bureau. Data from the current study came from the second wave of the NESARC collected between 2004 and 2005, as the harsh physical punishment assessment was included only in this wave of data collection. The second wave of the NESARC collected information from 34,653 adults aged 20 years and older living in households as well as non-institutionalized group dwellings. The response rate was 86.7% for Wave 2. Further details of the NESARC methodology and sampling procedures have been published elsewhere (Grant et al., 2004).

Participants were divided into 5 different birth cohorts based on their age and year of birth at the time of the survey (i.e., 20–29 years and born between 1975 and 1985; 30–39 years and born between 1965 and 1975; 40–49 years and born between 1955 and 1965; 50–59 years and born between 1945 and 1955; and 60–69 years and born between 1935 and 1945). Because issues related to recall bias would likely be most pronounced among the oldest respondents in the sample (e.g., cognitive decline, survivor bias, accurate recall of childhood experiences), participants aged 70 years and older were excluded from analyses.

Participants were also categorized according to self-identified race (i.e., non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or Hispanic). Due to low cell counts among other racial categories in certain age groups, participants self-identifying as American Indian/Alaska Native or Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander were excluded from analyses. All participants (regardless of racial identification) were included in analyses concerning sex differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment.

Measures

Harsh physical punishment

Harsh physical punishment was assessed with the question, “As a child, how often were you ever pushed, grabbed, shoved, slapped, or hit by your parents or any adult living in your house?” Harsh physical punishment was measured on a 5-point Likert scale (never, almost never, sometimes, fairly often, and very often), and participants were asked to report on experiences that occurred before the age of 18. Participants with a response of sometimes or greater to this question were considered as having experienced harsh physical punishment in childhood.

Other types of child maltreatment

Other types of child maltreatment assessed in the NESARC included physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, and exposure to intimate partner violence. Respondents were asked to report on child maltreatment experiences that occurred before the age of 18 years. With the exception of emotional neglect, all child maltreatment items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (never, almost never, sometimes, fairly often, and very often). The emotional neglect items were assessed on a similar 5-point Likert scale (never true, rarely true, sometimes true, often true, and very often true). For analyses examining age group, sex, and racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment, each type of child maltreatment was entered into models as covariates to adjust for the confounding between harsh physical punishment and other types of child maltreatment.

Physical abuse was defined as having ever been hit so hard that it left marks, bruises, or caused an injury by a parent or other adult living in the home. Sexual abuse was defined as having ever experienced any unwanted sexual touching or fondling, or any attempted or actual intercourse by an adult or other person that was unwanted or occurred when the respondent was too young to understand what was happening. Emotional abuse was defined as having often or very often experienced a parent or other adult living in the home: (a) swear at or insult the respondent; (b) threaten to hit or throw something at the respondent, but did not do it; or (c) act in any other way that made the respondent feel afraid.

Physical neglect was defined as having ever: (a) been left alone or unsupervised before age 10 years; (b) gone without needed things such as clothes, shoes, or school supplies because a parent or other adult living in the home spent the money on themselves; (c) been made to go hungry or did not have regular meals prepared; or (d) had a parent or other adult living in the home ignore or fail to get the respondent medical treatment. Emotional neglect in childhood was assessed with the following 5 items: (a) the respondent felt there was someone in the family who wanted them to be a success; (b) someone in the respondent’s family made them feel special or important; (c) the respondent’s family was a source of strength or support; (d) the respondent felt part of a close knit family; and (e) someone in the respondent’s family believed in them. Consistent with past research, these items were reverse-coded and summed; scores of 15 or greater were considered indicative of having experienced emotional neglect in childhood (Dong, Anda, Dube, Giles, & Felitti, 2003; Dube et al., 2003).

To determine whether the respondent was exposed to intimate partner violence in childhood, respondents were asked whether their mother’s partner had (a) pushed, grabbed, slapped, or thrown something at their mother, (b) kicked, bit, or hit their mother with a fist or something hard, (c) repeatedly hit their mother for at least a few minutes, or (d) threatened her with a knife or gun, or use a knife or gun to hurt her. Any response of sometimes or greater to items (a) or (b), or any response other than never to items (c) or (d), was considered exposure to intimate partner violence in childhood.

Sociodemographic covariates

Sociodemographic covariates included marital status (married/common-law, separated/divorced/widowed, never married), education level (less than high school, high school diploma, some post-secondary, completed college or university), past-year household income ($19,999 or less; $20,000–$39,999; $40,000–$69,999; $70,000 or more), and a proxy indicator of childhood socioeconomic status based on the participant’s response to the question: “Before you were 18 years old, was there ever a time when your family received money from government programs like welfare, food stamps, general assistance, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or Temporary Assistance for Needy families?” (yes/no). Participant sex (male/female) was included as a covariate in analyses examining racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment. Participant self-reported race (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander) was included as a covariate in analyses examining sex differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment.

Data analysis

Complex sampling weights were applied in all analyses to account for the stratified sampling strategy. Sampling weights were applied to ensure that the NESARC data were representative of the general U.S. population due to non-response and oversampling of specific groups in the sampling process (see Grant et al., 2004 for more details). Weighted data are representative of the U.S. population based on a number of sociodemographic indicators (e.g., region, age, sex, race, and ethnicity) from 2000 U.S. Census data (Grant et al., 2004). To account for the complex sampling design of the NESARC, Taylor series linearization was used as a variance estimation technique to adjust standard errors accordingly using SUDAAN software (Shah, Barnwell, & Biehler, 2004).

First, descriptive statistics involving cross tabulations were computed to examine the distribution of harsh physical punishment by sociodemographic variables. Second, descriptive statistics were computed to examine the prevalence of harsh physical punishment across the different age groups. Third, a series of nested logistic regression models were run to determine whether the prevalence of harsh physical punishment varied significantly across age groups. The first series were ran unadjusted (OR); the second series adjusted for sociodemographic covariates (AOR-1); and the third series adjusted for sociodemographic covariates and other types of child maltreatment (AOR-2) simultaneously. Interaction terms were entered into logistic regression models to examine sex and racial differences in harsh physical punishment across the different age groups. Because interaction terms were significant, separate multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine between and within age group differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment for each sex and racial group.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample by childhood experiences of harsh physical punishment with or without other child maltreatment are provided in Table 1. Both males and females were equally likely to report experiencing harsh physical punishment. Black and American Indian/Alaskan Native participants were more likely to experience harsh physical punishment and Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders were less likely to experience harsh physical punishment than White participants. Harsh physical punishment was more prevalent among separated, divorced, and widowed participants, but less prevalent among never married participants compared to married or common-law participants. Higher education (i.e., post-secondary vs. less than high school) and higher income (i.e., $40,000 or more vs. $19,999 or less) were associated with a lower prevalence of harsh physical punishment. Participants reporting government assistance receipt in childhood were more likely to report harsh physical punishment than those not receiving such assistance in childhood.

Table 1.

Sample sociodemographic characteristics by harsh physical punishment with or without other forms of child maltreatment.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | No harsh physical punishment with or without other child maltreatment, % (n) | Harsh physical punishment with or without other child maltreatment, % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 82.3 (10,173) | 17.7 (2,374) |

| Female | 82.6 (13,546) | 17.4 (3,088) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 83.1 (13,425) | 16.9 (2,943) |

| Black | 79.1 (4,486) | 20.9 (1,215) |

| Hispanic | 82.0 (4,685) | 18.0 (1,052) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 71.1 (357) | 28.9 (145) |

| Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 88.7 (766) | 11.3 (107) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/Common-law | 82.5 (13,649) | 17.5 (3,028) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 77.9 (4,763) | 22.1 (1,395) |

| Never Married | 85.6 (5,307) | 14.4 (1,039) |

| Education | ||

| Less than High School | 80.5 (3,080) | 19.5 (741) |

| High School | 81.7 (6,260) | 18.3 (1,468) |

| Some College/University | 81.1 (5,216) | 18.9 (1,346) |

| Post-Secondary Degree | 84.3 (9,163) | 15.7 (1,907) |

| Past-year household income | ||

| $19,999 or less | 80.9 (4,410) | 19.1 (1,083) |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 81.2 (5,801) | 18.8 (1,409) |

| $40,000–$69,999 | 83.1 (6,567) | 16.9 (1,446) |

| $70,000 or more | 83.4 (6,941) | 16.6 (1,524) |

| Government assistance receipt in childhood | ||

| No | 84.2 (20,138) | 15.8 (4,039) |

| Yes | 72.2 (3,391) | 27.8 (1,365) |

Note: % (n): percentage and number of respondents who experienced harsh physical punishment (with or without other types of child maltreatment) before age 18. Ns are for the sample, whereas percentages are weighted to be representative of the population.

The prevalence and odds of harsh physical punishment by age group are provided in Table 2. With the exception of the 60–69 year old age group, the prevalence of harsh physical punishment appeared to have been decreasing over time; from a high of 20.0% among the 50–59 year olds to a low of 13.7% among the 20–29 year olds. A similar pattern of decline over time is apparent with regard to the odds of having experienced harsh physical punishment in childhood. The odds of having experienced harsh physical punishment before age 18 years was significantly lower among the youngest age groups (i.e., 20–39 years of age) compared to participants 60–69 years of age, even after adjusting for the effects of sociodemographic variables and other forms of child maltreatment.

Table 2.

Prevalence and odds of harsh physical punishment by age group in the general U.S. population.

| Age (in years) | Birth cohort | Prevalence of HPP, % (n) | OR [95% CI] | AOR-1 [95% CI] | AOR-2 [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60–69 | Born 1935–1945 | 17.8 (754) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 50–59 | Born 1945–1955 | 20.0 (1,308) | 1.2* [1.03, 1.3] | 1.1* [1.01, 1.3] | 1.0 [0.8, 1.1] |

| 40–49 | Born 1955–1965 | 18.7 (1,463) | 1.1 [0.9, 1.2] | 1.0 [0.9, 1.2] | 0.9 [0.8, 1.0] |

| 30–39 | Born 1965–1975 | 17.2 (1,213) | 1.0 [0.9, 1.1] | 0.9 [0.8, 1.0] | 0.8** [0.7, 0.9] |

| 20–29 | Born 1975–1985 | 13.7 (724) | 0.7*** [0.6, 0.9] | 0.7*** [0.6, 0.8] | 0.7** [0.6, 0.9] |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 27,016.5 (4) | 26,258.9 (18) | 17,706.6 (24) | ||

| Model Wald χ2 | 950.9*** | 262.6*** | 286.8*** |

Note: % (n): percentage and number of respondents who experienced harsh physical punishment (with or without other types of child maltreatment) before age 18. Ns are for the sample, whereas percentages are weighted to be representative of the population. OR = odds ratio (unadjusted); AOR-1 = odds ratio adjusted for sex, race, marital status, past-year household income, and childhood government assistance receipt; AOR-2 = odds ratios adjusted for sociodemographics (AOR-1) plus other forms of child maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and exposure to intimate partner violence); HPP = Harsh physical punishment; CI = confidence interval.

p ≤ 0.05.

p ≤ 0.01.

p ≤ 0.001.

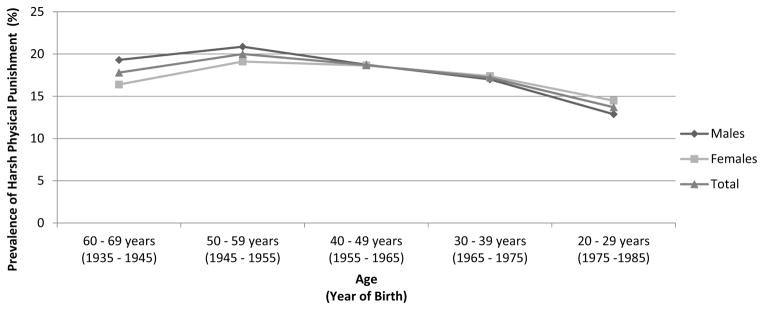

A visual depiction of differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment over time by sex and race are provided in Fig. 1 (sex differences) and Fig. 2 (racial differences). As shown in Fig. 1, the prevalence of harsh physical punishment in childhood reported by males appeared to steadily decrease over time; from highs of 19.3% among the 60–69 year olds and 20.9% among 50–59 year olds to a low of 12.9% among 20–29 year olds. Between age group analyses indicated that males in the two youngest age cohorts (i.e., 20–39 years old) reported significantly lower odds of experiencing harsh physical punishment than males 60–69 years old, even after adjusting for the effects of sociodemographic variables and other types of child maltreatment (see Table 3). The pattern for females is less consistent than for males. Females in the oldest age group (i.e., 60 years and older) reported a prevalence of harsh physical punishment similar to, and not significantly different from, females in the youngest age groups (i.e., <40 years old). Compared to males, a less marked decrease in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment was seen over time among females born after 1945; 18.7% of female participants 50–59 years of age experienced harsh physical punishment before age 18 compared to 14.5% of females 20–29 years of age. No significant differences were found in the odds of harsh physical punishment between the different age cohorts for females (see Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of harsh physical punishment by age group and sex.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of harsh physical punishment by age group and race.

Table 3.

Between age group sex and racial differences in the odds of harsh physical punishment in the general U.S. population.

| Age (year of birth) | Sex

|

Race

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male AOR [95% CI] |

Female AOR [95% CI] |

White AOR [95% CI] |

Black AOR [95% CI] |

Hispanic AOR [95% CI] |

|

| 60–69 years (1935–1945) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 50–59 years (1945–1955) | 0.9 [0.7, 1.1] | 1.0 [0.8, 1.3] | 1.0 [0.8, 1.1] | 1.0 [0.7, 1.3] | 1.3 [0.7, 2.5] |

| 40–49 years (1955–1965) | 0.8 [0.7, 1.01] | 1.0 [0.8, 1.3] | 0.9 [0.7, 1.1] | 0.9 [0.6, 1.2] | 1.1 [0.6, 2.1] |

| 30–39 years (1965–1975) | 0.7** [0.5, 0.9] | 0.9 [0.7, 1.2] | 0.7*** [0.5, 0.8] | 0.9 [0.6, 1.4] | 1.3 [0.6, 2.6] |

| 20–29 years (1975–1985) | 0.6*** [0.4, 0.8] | 0.8 [0.7, 1.2] | 0.6*** [0.4, 0.7] | 1.0 [0.7, 1.5] | 1.3 [0.7, 2.4] |

| Model statistics | |||||

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 8,040.7 (23) | 9,514.2 (23) | 9,647.7 (20) | 4,190.1 (20) | 3,505.3 (20) |

| Model Wald χ2 | 156.1*** | 220.7*** | 262.8*** | 86.0*** | 57.0*** |

Note: AOR = odds ratios adjusted for sociodemographics (i.e., sex, race, marital status, education, past-year household income, and government assistance receipt in childhood) and other forms of child maltreatment experienced before age 18 (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, and exposure to intimate partner violence). Independent variables were entered simultaneously into each model. CI = confidence interval.

p ≤ 0.05.

p ≤ 0.01.

p ≤ 0.001.

To examine sex differences in harsh physical punishment within the different age groups, an age group by sex interaction term was entered into logistic regression models, Wald χ2 = 5.32, interaction term OR = 0.9, 95% CI [0.85, 0.99], p = 0.02443. As shown in Table 4, females consistently reported significantly lower odds of harsh physical punishment than males among respondents 30 years and older; however, the difference in odds was closer to null and not significantly different in the most recently born age group.

Table 4.

Within age group sex and racial differences in odds of harsh physical punishment in the general U.S. population.

| Age (year of birth) | Sex

|

Race

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males Reference group |

Females AOR [95% CI] |

Whites Reference group |

Blacks AOR [95% CI] |

Hispanics AOR [95%CI] |

|

| 60–69 years (1935–1945) | 1.0 | 0.6*** [0.5, 0.8] | 1.0 | 1.1 [0.8, 1.5] | 0.8 [0.5, 1.3] |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 2,682.8 (20) | 2,639.0 (18) | |||

| Model Wald χ2 | 62.43*** | 66.4*** | |||

| 50–59 years (1945–1955) | 1.0 | 0.7*** [0.5, 0.8] | 1.0 | 1.1 [0.9, 1.5] | 1.0 [0.7, 1.3] |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 3,999.6 (20) | 3,896.8 (18) | |||

| Model Wald χ2 | 96.6*** | 100.6*** | |||

| 40–49 years (1955–1965) | 1.0 | 0.8* [0.6, 0.95] | 1.0 | 1.1 [0.8, 1.4] | 0.9 [0.7, 1.2] |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 4,642.0 (20) | 4,439.1 (18) | |||

| Model Wald χ2 | 114.6*** | 121.1*** | |||

| 30–39 years (1965–1975) | 1.0 | 0.8* [0.7, 0.99] | 1.0 | 1.6* [1.1, 2.4] | 1.3 [0.96, 1.8] |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 3,746.8 (20) | 3,588.0 (18) | |||

| Model Wald χ2 | 84.2*** | 86.2*** | |||

| 20–29 years (1975–1985) | 1.0 | 0.9 [0.7, 1.2] | 1.0 | 1.8*** [1.3, 2.6] | 1.6* [1.1, 2.3] |

| −2 Log likelihood (df) | 2,553.3 (20) | 2427.4 (18) | |||

| Model Wald χ2 | 79.5*** | 85.3*** | |||

Note: Interaction terms for age group * sex (Wald χ2 = 5.32, p = 0.02) and age group * race (Wald χ2 = 16.30, p < 0.0001) were entered into a logistic regression model and found to be significant. Therefore, sex and racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment (with or without other forms of maltreatment) were examined with reference to specific age groups. AOR = odds ratios adjusted for sociodemographics (i.e., sex, race, marital status, education, past-year household income, and government assistance receipt in childhood) and other forms of child maltreatment experienced before age 18 (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, and exposure to intimate partner violence). Independent variables were entered simultaneously into each model. CI = confidence interval.

p ≤ 0.05.

p ≤ 0.01.

p ≤ 0.001.

As shown in Fig. 2, racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment across the different age cohorts seem apparent. Among non-Hispanic White participants, results suggested that the prevalence of harsh physical punishment has been steadily decreasing since 1945; from a high of 19.6% among 50–59 year olds to a low of 11.3% in the youngest age group. Among non-Hispanic Black respondents, however, the prevalence of harsh physical punishment appeared to be fairly consistent over time with no statistically significant differences found across the different age groups. Finally, for Hispanic respondents, the prevalence of harsh physical punishment increased from a low of 14.2% among Hispanics 60–69 years of age to a high of 20.1% among Hispanics 50–59 years of age. For Hispanics born after 1945, the prevalence of harsh physical punishment has remained fairly consistent across the different age groups. As shown in Table 3, between age group analyses indicated that non-Hispanic White participants in the two youngest age cohorts (i.e., 20–39 years old) had significantly lower odds of experiencing harsh physical punishment than White participants 60–69 years of age. No significant differences in the odds of harsh physical punishment were found across age groups for participants self-identifying as non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic.

To examine racial differences in harsh physical punishment within the different age groups, an age group by race interaction term was entered into logistic regression models, Wald χ2 = 16.30, interaction term OR = 0.9, 95% CI [0.8, 0.94], p = 0.0001. As shown in Table 4, within age group analyses indicated that in the older age groups (i.e., 40 years and older), non-Hispanic Black participants reported similar odds of harsh physical punishment before age 18 than non-Hispanic White participants. In the youngest age groups (i.e., <40 years old), non-Hispanic Blacks report significantly elevated odds of having experienced harsh physical punishment than non-Hispanic Whites, even after adjusting for the effects of sociodemographic covariates and other forms of child maltreatment. Finally, although Hispanic participants appeared to have lower odds of experiencing harsh physical punishment in childhood than non-Hispanic Whites in the older age groups (i.e., those born 1965 and earlier), this trend has reversed in more recently born age groups (i.e., those born 1965 and later), with Hispanic participants 20–29 years of age reporting significantly higher odds of harsh physical punishment than same age non-Hispanic White participants in the fully adjusted model

Discussion

This study makes several novel contributions to the child maltreatment literature, and can be used to better inform child maltreatment prevention and intervention strategies. Notably, although the prevalence of harsh physical punishment appears to be decreasing over time, this pattern of decrease is not consistent when examining sex and racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment between and within different age groups.

Sex comparisons indicated that the prevalence of physical punishment has, for the most part, been decreasing for both males and females over time. A number of studies have reported that males are more likely to experience harsh physical punishment compared to females (Afifi et al., 2014; Dietz, 2000; Douglas & Straus, 2006; Straus, 2001). Our results are consistent with previous research in the older age groups; however, an interesting finding in the current study was that the traditionally lower prevalence of harsh physical punishment reported among females has largely disappeared, and parity in rates of harsh physical punishment across gender was found in the youngest age group in this sample. Nonetheless, since 12.9% of males and 14.5% of females in the most recently born age cohorts experience harsh physical punishment is cause for concern given evidence of the associations between harsh physical punishment and poor health outcomes (Afifi et al., 2014, 2012, 2013; Bender et al., 2008; Cheng, Anthony, & Huang, 2010; Hardt et al., 2008; Lynch et al., 2006).

With regard to racial differences, the prevalence of harsh physical punishment among non-Hispanic Black participants has remained stable across the different age groups. Less research exists regarding the physical punishment of Hispanic children, but findings from this study indicate that the prevalence of harsh physical punishment may actually be increasing over time. However, further research is needed to confirm this possible trend. These findings are consistent with research indicating that recent declines in harsh physical punishment may not be equal for all racial or ethnic groups (Hawkins et al., 2010; Sedlak et al., 2010). Research has suggested that racial variations in the effects of harsh physical punishment exist (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996; Foshee, Ennett, Bauman, Benefield, & Suchindran, 2005; Horn, Joseph, & Cheng, 2004; Polaha, Larzelere, Shapiro, & Pettit, 2004). This could be due, in part, to the extent to which both parents and children perceive physical punishment as culturally acceptable (Deater-Deckard et al., 1996; Lorber et al., 2011; McLoyd, Kaplan, Hardaway, & Wood, 2007). However, there is a growing body of research using longitudinal and/or nationally representative research designs that indicates that the effects of harsh physical punishment are detrimental across races (Coley, Kull, & Carrano, 2014; Gershoff, 2013; Gershoff et al., 2012; Grogan-Kaylor, 2004, 2005) and regardless of its perceived normativeness within a specific cultural group (Coley et al., 2014; Gershoff et al., 2010; Lansford et al., 2005). Thus, although cultural acceptance of physical punishment likely plays a role in a parent’s decision to use physical discipline, it does not protect children from the potential harms.

One problem in the extant research is the correlation between race and socioeconomic status, both of which have been associated with more frequent use of harsh physical punishment. The current study used a proxy indicator for childhood socioeconomic status (i.e., government assistance receipt in childhood) in an effort to better understand the role of race independent of socioeconomic status. However, our measure of childhood socioeconomic status has limitations and may not fully capture childhood socioeconomic circumstances. Therefore, it could be that the differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment across racial groups reported in this study are attributable to socioeconomic factors rather than race per se. Nonetheless, because non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanic participants were significantly more likely to experience harsh physical punishment before age 18 than non-Hispanic Whites in the most recently born age group suggests that more targeted intervention and prevention strategies for specific groups may be required.

The findings from this research need to be viewed in light of a number of limitations. First, the data were cross-sectional, which limits the ability to examine trends over time. As well, we are unable to make inferences about causality. Second, the data were collected retrospectively and participants were asked to report on childhood experiences that may have occurred decades earlier, which introduces the possibility of recall and reporting bias. However, it is also important to note that evidence exists that supports the validity of accurate recall of adverse childhood events (Hardt & Rutter, 2004). Third, the fact that low cell counts precluded examination of differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment among other self-identified racial groups (i.e., American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander categories) suggests an important area for future research. It is also important to note that substantial heterogeneity exists within the Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black communities within the United States, and we were unable to account for important within group differences within these highly diverse cultural groups. Fourth, as previously mentioned, the measure of childhood socioeconomic status used in this study may not have comprehensively captured childhood socioeconomic circumstances and is viewed as an important limitation of this study.

Finally, the prevalence of harsh physical punishment reported here may not be directly comparable to rates reported elsewhere. Because this research examined harsh physical punishment, which could include acts of physical force outside the realm of what is normally considered non-abusive, customary physical punishment (e.g., spanking or slapping), findings may not be directly comparable to studies examining spanking alone. However, the study represents an attempt to capture a measure of physical punishment, albeit potentially harsher than spanking alone, that remains legal in the United States and closely approximates a type of physical aggression often used in childrearing. With laws in North America that allow for physical discipline of children, the line demarcating physical punishment from physical abuse is not clear. As a supplementary analysis, we reran our analyses to include any type of physical aggression (i.e., measures of harsh physical punishment and/or physical abuse combined) as the outcome. Results did not substantively change (see supplementary tables and figures available online). This suggests that both harsh physical punishment and physical abuse more generally are decreasing in more recently born cohorts, albeit not equally experienced across racial groups.

Consistent with evidence suggesting a global shift in attitudes toward less acceptability and legitimacy of physical punishment as a disciplinary technique, the prevalence of harsh physical punishment appears to have been decreasing for both sexes over time. However, the same decrease is not noted when examining racial differences in the prevalence of harsh physical punishment both within and across different age groups. Prevention and intervention efforts that educate about the links of physical punishment to negative outcomes and alternative non-physical discipline strategies may be particularly useful in reducing the prevalence of harsh physical punishment over time. All children share the basic human right to be free from physical and mental harm (United Nations, 1989); thus, continued efforts to eliminate all forms of physical punishment in childrearing among all children is one integral step toward achieving this goal.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.020.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Afifi TO, Brownridge DA, Cox BJ, Sareen J. Physical punishment, childhood abuse, and psychiatric disorders. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30(10):1093–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.04.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan HL, Boyle M, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Sareen J. Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2014;186(9):E324–E332. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131792. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.131791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, Mota N, Dasiewicz P, MacMillan HL, Sareen J. Physical punishment and mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative US sample. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):184–192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2947. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, Mota N, MacMillan HL, Sareen J. Harsh physical punishment in childhood and adult physical health. Pediatrics. 2013;132(2):e333–e340. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-4021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The discipline encounter: Contemporary issues. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2(4):321–335. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D, Larzelere RE, Cowan PA. Ordinary physical punishment: Is it harmful? Comment on Gershoff (2008) Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(4):580–589. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.580. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-909.128.4.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender HL, Allen JP, Boykin McElhaney K, Antonishak J, Moore CM, O’Beirne Kelly H, Davis SM. Use of harsh physical discipline and developmental outcomes in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;19:227–242. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensley L, Ruggles D, Simmons KW, Harris C, Williams K, Putvin T, Allen M. General population norms about child abuse and neglect and associations with childhood experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:1321–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Ispa JM, Fine MA, Malone PS, Brooks-Gunn J, Brady-Smith C, Bai Y. Correlates and consequence of spanking and verbal punishment for low-income White, African American, and Mexican American toddlers. Child Development. 2009;80(5):1403–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Paediatric Association. Effective discipline for children: Position statement [PP 2004-01] Paediatrics and Child Health. 2004;9(1):37–41. doi: 10.1093/pch/9.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Psychological Association. Policy statement on physical punishment of children and youth. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Psychological Association; 2004. Retrieved from: http://www.cpa.ca/documents/policy3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HG, Anthony JC, Huang Y. Harsh physical punishment as a specific childhood adversity linked to adult drinking consequences: Evidence from China. Addiction. 2010;105:2097–2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03079.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Kull MA, Carrano J. Parental endorsement of spanking and children’s internalizing and externalizing problems in African American and Hispanic families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28(1):22–31. doi: 10.1037/a0035272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0035272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(6):1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz TL. Disciplining children: Characteristics associated with the use of corporal punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(12):1529–1542. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00213-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, Felitti VJ. The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(6):625–639. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00105-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas EM, Straus MA. Assault and injury of dating partners by university students in 19 countries and its relation to corporal punishment experienced as a child. European Journal of Criminology. 2006;3(3):293–318. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1477370806065584. [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):564–572. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.564. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.3.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE. Physical punishment, culture, and rights: Current issues for professionals. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2008;29:55–66. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318135448a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e318135448a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant JE, Ensom R. Physical punishment of children: Lessons from 20 years of research. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184(12):1373–1377. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.101314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Jones L. Why have child maltreatment and child victimization declined? Journal of Social Issues. 2006;62(4):685–716. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby SL. The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(1):5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Benefield T, Suchindran C. The association between family violence and adolescent dating violence onset: Does it vary by race, socioeconomic status, and family structure? The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2005;25(3):317–344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0272431605277307. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviours and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(4):539–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Report on physical punishment in the United States: What research tells us about its effects on children. Columbus, OH: Center for Effective Discipline; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Spanking and child development: We know enough now to stop hitting our children. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7(3):133–137. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A, Lansford JE, Chang L, Zelli A, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Parent discipline in an international sample: Associations with child behaviors and moderation by perceived normativeness. Child Development. 2010;81(2):487–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Lansford JE, Sexton HR, Davis-Kean P, Sameroff AJ. Longitudinal links between spanking ad children’s externalizing behaviors in a national sample of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian American families. Child Development. 2012;83(3):838–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Initiative to End all Corporal Punishment of Children. Countdown to universal prohibition. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.endcorporalpunishment.org.

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou P, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan-Kaylor A. The effect of corporal punishment on antisocial behavior in children. Social Work Research. 2004;28(3):153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Grogan-Kaylor A. Corporal punishment and the growth trajectory of children’s antisocial behavior. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(3):283–292. doi: 10.1177/1077559505277803. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559505277803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Self-Brown S, Fricker-Elhai AE, Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE, Resnick HS. The relations between family environment and violence exposure among youth: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/1077559505279295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559505279295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Sidor A, Nickel R, Kappis B, Petrak P, Egle UT. Childhood adversities and suicide attempts: A retrospective study. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:713–718. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-008-9196-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AO, Danielson CK, de Arellano MA, Hanson RF, Ruggiero KJ, Smith DW, Kilpatrick DG. Ethnic/racial differences in the prevalence of injurious spanking and other child abuse in a national survey of adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15(3):242–249. doi: 10.1177/1077559510367938. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077559510367938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn IB, Joseph JG, Cheng TL. Nonabusive physical punishment and child behavior among African-American children: A systematic review. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96(9):1162–1168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Chang L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Palmérus K, Quinn N. Physical discipline and children’s adjustment: Cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development. 2005;76(6):1234–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-624.2005.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, O’Leary SG, Smith Slep AM. An initial evaluation of the role of emotion and impulsivity in explaining racial/ethnic differences in the use of corporal punishment. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(6):1744–1749. doi: 10.1037/a0025344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SK, Turkheimer E, Slutske WS, D’Onofrio BM, Mendle J, Emery RE. A genetically informed study of the association between harsh physical punishment and offspring behavioral outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(2):190–198. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.0.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie MJ, Nicklas E, Brooks-Gunn J, Waldfogel J. Who spanks infants and toddlers? Evidence from the Fragile Families and Child Well-Being Study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:1364–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Kaplan R, Hardaway CR, Wood D. Does endorsement of physical discipline matter? Assessing moderating influences on the maternal and child psychological correlated of physical discipline in African American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(2):165–175. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaha J, Larzelere RE, Shapiro SK, Pettit GS. Physical discipline and child behavior problems: A study of ethnic group differences. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4(4):339–360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327922par0404_6. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Green A, Li S. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4): Report to congress, executive summary. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Biehler GS. SUDAAN user’s guide manual: Release [9.0] Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shelov SP, Altman TR, editors. Caring for your baby and young child: Birth to age 5. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BL. The case against spanking. Monitor on Psychology. 2012;43(4):60. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Beating the devil out of them: Corporal punishment in American families and its effects on children. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Prevalence, societal causes, and trends in corporal punishment by parents in world perspective. Law and Contemporary Problems. 2010;73(2):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Stewart JH. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2(2):55–70. doi: 10.1023/a:1021891529770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. The Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations; 1989. Adopted by the General Assembly Resolution 44/45, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Whipple EE, Richey CA. Crossing the line from physical discipline to child abuse: How much is too much? Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(5):431–444. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor AJ, Puzia ME. Bans against corporal punishment: A systematic review of laws, attitudes and behaviours. Child Abuse Review. 2010;19(4):229–247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/car.1131. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor AJ, Theodore AD, Runyan DK, Chang JJ, Laskey AL. Corporal punishment and physical abuse: Population-based trends for three-to-11-year-old children in the United States. Child Abuse Review. 2011;20(1):57–66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/car.1128. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.