Osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of disability in the United States and globally, [14; 39] and the burdens it causes are expected to increase as the world’s population ages [14; 23]. Non-pharmacological treatments are a recommended component of current guidelines for treating OA pain [53]. Although evidence is mixed that people benefit from non-pharmacological treatments such self-management interventions and patient education [e.g., 17; 25; 38; 45], one non-pharmacological therapy—pain coping skills training (PCST)—has demonstrated more consistently positive outcomes [38]. PCST focuses specifically on educating people about cognitive and behavioral pain coping skills and helping them master those skills so they can become more actively involved in managing their pain--the most common and debilitating OA symptom [33]. It includes two main components: 1) a rationale linking pain to patterns of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral pain responses, and 2) training in skills such as attention diversion (e.g., relaxation), cognitive restructuring (to address catastrophizing and other maladaptive cognitive patterns), and activity patterns (e.g., activity-rest cycling). It has traditionally been delivered in-person by a trained therapist over 10-12 weeks. Randomized controlled trials demonstrate that PCST significantly improves pain and other outcomes [e.g., 24; 29; 30; 31; 63]. Moreover, interventions such as PCST have fewer adverse effects than pharmacological pain treatments and are well-received by patients.

Thus, research supports the efficacy of in-person PCST. However, access to this intervention is limited by barriers such as lack of trained therapists, the substantial resources needed to deliver it, and the need for people to travel to in-person training held at scheduled times [22; 59] There is a clear need for an approach that makes PCST more accessible. The Internet—a proven method for delivering behavioral interventions—provides an avenue for meeting this need [15; 42; 58; 65], especially given older adults’ increasing use of the Internet [69].

The present pilot study was a two-arm randomized controlled trial conducted to evaluate the potential efficacy and acceptability of an eight-week, automated, Internet-based version of PCST called PainCOACH. This program was designed to retain key therapeutic features of the in-person PCST protocol, simulating in-person PCST while presenting training in an easy-to-use format with guided instruction, individualized feedback, interactive exercises, and animated demonstrations [57]. We hypothesized that: (1) PainCOACH would reduce pain (primary outcome) and improve pain-related interference with functioning, pain-related anxiety, self-efficacy for pain management, and positive and negative affect; and (2) acceptability would be high. Our overarching goal was to use findings from this early-stage research to refine the program and study protocol in preparation for a larger-scale trial.

Additionally, we explored sex differences in responses to PainCOACH, based on evidence in our own lab and others showing significant sex differences in pain, pain responses, pain behavior, and pain coping in people with OA [e.g., 1; 19; 27; 32; see 54; 62; 67]. The potential for men and women to respond differently to pain interventions is important but rarely evaluated in research.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from two study sites from October 2012 to May 2013. At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), individuals with knee or hip OA were recruited for screening from the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project (JoCo OA), a community-based cohort of non-institutionalized men and women from six townships in Johnston County, North Carolina. This area is largely rural and, on average, low income [26], suggesting that these participants might have low access to services such as in-person PCST. The JoCo OA study established OA using radiographs with Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) radiographic grade of 2 or more in at least one knee or hip and affirmative responses to the following question for each joint separately: “On most days, do you have pain, aching, or stiffness in your [right, left] [knee, hip].” Symptomatic OA required the presence of pain, aching or stiffness and radiographic OA in the same joint. At Duke University Medical Center, potentially eligible individuals were identified for screening using medical or research records. They were individuals with clinically confirmed OA in one or both knees and/or hips who received care through Duke medical or surgical clinics or the Duke Pain and Palliative Care Clinic. Two additional individuals at Duke were recruited through participant referrals; their OA diagnosis was verified by their physicians. Screening was implemented with a telephone screening interview conducted by trained staff at the potential participant’s study site.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants were adults (≥18 years old) with knee or hip OA, confirmed radiographically (KL grade ≥2, with pain in the affected joint), with American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria [3; 4], or by their physician. They had to speak English and report having frequent OA pain (defined as pain on most days of the month for each of the prior three months). Individuals were excluded from participating if they had significant cognitive impairment (3 or more incorrect responses on a validated six-item screener) [9]; less than 7th grade reading proficiency (three-item health literacy screener) [10]; or medical comorbidities that interfered with their ability to complete the intervention or that indicated they had a pain-related condition in addition to OA (uncorrectable moderate or severe hearing or vision deficits, Parkinson’s disease, cancer pain, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, diabetic neuropathy, arthroscopic surgery or total knee- or hip- replacement surgery in the past six months, fractures in the past six months, history of falls in the past three months, or vertigo in the past month).

Trial design and randomization

This study used a multi-center, balanced (1:1) randomization, assessor-blinded, parallel-group design. It included assessments at baseline (prior to randomization), midway through the intervention period (midpoint assessment), and after completion of the intervention (post-intervention assessment, approximately 9 to 11 weeks after randomization). The midpoint assessment was included to evaluate the possibility that participants could begin experiencing benefits before completing the full program. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT01638871).

Randomization was implemented using computer-generated permuted block randomization (with random block sizes varying from 2 to 12) stratified by sex and site. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two treatment conditions (PainCOACH or assessment only control) using a 1:1 ratio. Sequentially-numbered opaque envelopes were used to conceal allocation until after the baseline assessment.

Study flow

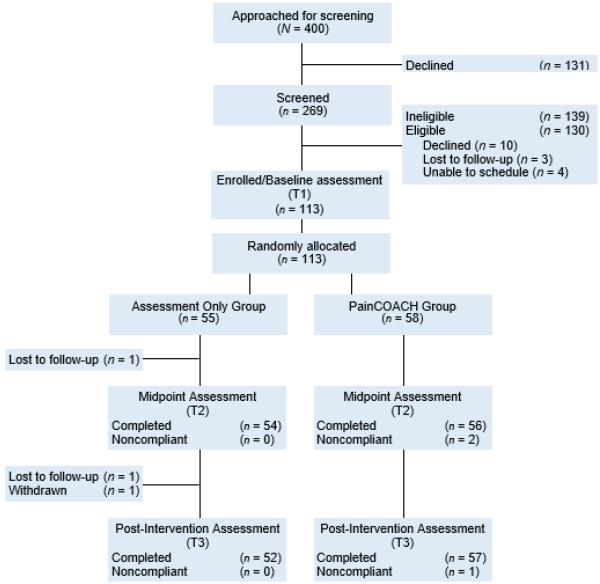

Figure 1 shows a CONSORT flow diagram depicting participants’ progression through the study design. As shown, 400 individuals were approached for recruitment into screening. Of the 131 who declined screening, 21% of them (n=28) provided information that indicated they would have been ineligible (e.g., a reason for declining that involved having no arthritis, little or no joint pain in hips/knees, serious hearing/vision problems, self-reported low literacy, recent or scheduled hip/knee surgery, or a health problem that would exclude them). The remaining 103 gave one or more reasons for declining screening, mostly involving not having time (n=33), health problems (n=28), not being interested (n=25), and not wanting to use a computer (n=24). Potential participants who declined screening or enrollment were significantly older than those who agreed to screening and/or enrollment (M=72.6, SD=8.8 vs. M=69.0, SD=9.8, respectively, p=.001) and men tended to be more likely than women to decline (38.1% of men vs. 27.6% of women; p=.05). There were no significant race/ethnicity differences in agreement to be screened.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of trial.

Of the 269 individuals who completed screening, 139 were not eligible. Because screening ended after certain ineligibility criteria were met, it is not possible to report all reasons for ineligibility. However, hip/knee pain was the first criterion in the interview and 53% of those screened reported insufficiently frequent arthritis pain in their hips or knees to be eligible. In addition, 10 individuals were eligible but declined to continue, 3 were lost to follow-up after screening, and 4 did not attend the baseline visit at which enrollment occurred and could not be rescheduled. Thus, 113 participants were enrolled, completed the baseline assessment, and were randomized to the PainCOACH group (n = 58) or assessment only control group (n = 55). The unequal group sizes resulted from our use of blocking in the randomization. The attrition rate from baseline to post-intervention was 3.5%; two participants did not attend their post-intervention visit and then could not be contacted to reschedule, one did not complete the post-intervention assessment because of a painful shoulder condition and impending surgery, and one was withdrawn from the study due to serious illness. Five PainCOACH participants did not complete some (n=2) or all (n=3) intervention sessions but did complete the post-intervention assessment. Accordingly, their post-intervention data were analyzed (i.e., we used an intent-to-treat approach). Participants who completed study activities did not differ significantly from non-completers (those who dropped out of the study or who did not complete all PainCOACH sessions) on any sociodemographic, medical, or outcome variable.

Procedures

Trained research staff telephoned potential participants for recruitment into the screening protocol. A scripted description was used to explain that the study was for people with arthritis pain in their hips or knees and that it focused on teaching people to use pain coping skills using a computer program. The time commitment was explained, as was the fact that a tablet computer would be loaned to people who needed it. Participants who were eligible based on screening and who agreed to continue were scheduled for an in-person baseline visit at their study site.

The baseline visit took place at participants’ study site and began with informed consent procedures. After signed consent was obtained, a blinded, trained staff member led participants through completion of the baseline questionnaire. Following completion of the questionnaire, the staff member revealed participants’ randomized study assignment, becoming unblinded in the process, and provided instructions appropriate to the assigned treatment condition. For PainCOACH participants, those instructions included receiving a loaned tablet computer and being shown how to use it to access the PainCOACH program. PainCOACH participants also completed a brief supplementary questionnaire only relevant to study participants using the program. To reduce the probability of compliance problems observed in some Internet-based interventions [18; 52], the staff member then used motivational interviewing techniques [50] to ask questions designed to enhance participants’ motivation to complete the entire PainCOACH program. Specifically, the supplementary questionnaire included a question asking participants to rate how important it was to them to complete the PainCOACH program. Participants who provided an answer other than “extremely important” were asked their reasons for their response and what it would take to get their response closer to “extremely important.” The staff member led them in a brief discussion during which they generated reasons for completing the program, barriers to doing so, and solutions. The discussion was then summarized by the staff member in a manner consistent with a motivational interviewing approach.

Before ending the baseline visit, participants in both treatment conditions were given instructions in how and when they would complete the midpoint and post-intervention assessments. They left with a midpoint questionnaire sealed in an envelope, with instructions not to open and complete it until a staff member phoned to instruct them to do so. A date and time for that call was scheduled for approximately 5 weeks from the date of the baseline visit (corresponding to the time at which PainCOACH participants would have completed four of the eight program training modules). Participants were also asked not to tell any other staff members their randomized study assignment unless specifically asked to do so.

For the midpoint assessment, an unblinded staff member phoned participants at the scheduled time and, using scripted instructions that ensured the call would be brief and highly structured, asked them to open the midpoint assessment packet, complete the questionnaire, and return it using the postage paid return envelope provided in the packet.

The post-intervention assessment occurred in-person at participants’ study sites approximately 9-11 weeks after baseline (about a week after PainCOACH participants completed the last of the program’s eight training modules). Several steps were taken to ensure that the staff conducting this visit were blind to the participants’ randomized study assignment. First, at the time the visit was scheduled, participants were reminded not to mention their group assignment during the visit and not to provide any information that would reveal it until specifically asked to do so. Additionally, PainCOACH participants were met by an unblinded staff member who collected their tablet computer before meeting with a blinded staff member who administered the follow-up questionnaires.

Compensation was provided to participants as follows: $40 for the baseline assessment, $40 for the midpoint assessment, and $80 for the post-intervention assessment. The study was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Boards of UNC, Duke University, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (sponsor).

Treatment conditions

Internet-based PCST (PainCOACH)

Participants in this condition used the PainCOACH program, which translated an in-person PCST protocol [28] for delivery via the Internet. The translation processes used procedures designed to ensure the program retained key therapeutic components of the in-person protocol. It included eight modules completed in a self-directed manner (i.e., without therapist contact) at the rate of one per week. Each module took 35-45 minutes to complete and provided interactive training in a cognitive or behavioral pain coping skill. As in the in-person PCST protocol, participants were asked to practice each new skill after learning it. Their completion of and experiences with practices were reviewed at the beginning of the next module. A summary of the content and flow of the modules is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of PainCOACH Modules

| Coping Skill | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Progressive muscle relaxation |

|

| 2 | Mini-practices |

|

| 3 | Activity/rest cycling |

|

| 4 | Pleasant activity scheduling, Negative automatic thoughts |

|

| 5 | Negative automatic thoughts, Coping thoughts |

|

| 6 | Pleasant imagery and other distraction techniques |

|

| 7 | Problem Solving |

|

| 8 | Monitoring for maintenance |

|

Participants were led through the program by a female “virtual coach” who greeted participants at the beginning of each module and provided verbal instruction, feedback, and encouragement throughout each module. Important points in her dialogue were accentuated with onscreen text or illustrated with graphics. Learning was also reinforced with theoretically-based methods drawn from social cognitive theory [5; 6], adult learning theory [36; 37], and principles of multimedia instruction [e.g., 46]. For instance, program elements based on social cognitive theory included interactive exercises to enhance mastery of new skills, persuasive arguments regarding participants’ ability to complete tasks (social persuasion), and observation of similar others (characters that represented average members of the target population who modeled use of pain coping skills). The modules and other program features were accessed through a home page (see online supplement). Other features included the ability to review all or part of completed modules (e.g., accessed through a toolbox icon on the home page menu next to completed modules), optional automated practice reminders, encouraging messages, badges earned by completing training modules and selected tasks (e.g., practices), self-monitoring (i.e., a section called COACHtrack used to manage practice reminders, log and view graphs showing progress, and set/revise practice goals), and a section of the website that enabled participants to read about others’ experiences using pain coping skills and to post their own experiences (COACHchat). Program modules and features were controlled by programming that used decision rules to customize participants’ experience based on their responses and progress through the program (e.g., offering suggestions to practice more and tips for doing so when participant responses indicated no or little practice). Features of this programming are described elsewhere [57]; it used an “expert systems approach” in that its tailoring and algorithms were guided by the expertise of therapists with extensive experience delivering in-person PCST.

Participants accessed the program at home through a wireless high-speed broadband connection or a 4G LTE high-speed Internet connection provided by the study. They also received a companion hard-copy workbook that reviewed how to use the tablet computer and PainCOACH, provided an overview of modules and features, and included worksheets.

Assessment only (control)

Participants in this condition completed the baseline, midpoint, and post-intervention assessments on the same schedule and using the same procedures as participants in the PainCOACH condition. They were not offered access to PainCOACH at any point during or after the study.

Primary outcome measure

Pain in the prior month was assessed with the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale 2 (AIMS2) 5-item arthritis pain subscale [49]. Respondents reported the severity of their usual arthritis pain (1=severe to 5=none) as well as the frequency of severe pain, pain in two or more joints at the same time, morning stiffness lasting more than one hour after waking, and difficulty sleeping due to pain (1=no days to 5=all days). The first item was reverse coded and responses were summed and normalized to produce possible scores ranging from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater pain. Internal reliability was adequate at all study assessments (Cronbach’s alphas of .74 to .78)

Secondary outcome measures

Self-efficacy for pain management was measured with the 8-item version of the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale [40], which assesses participants’ confidence in their ability to manage their arthritis pain and its effects on functioning on a scale from 1 (very uncertain) to 10 (very certain). Responses were averaged so that higher scores indicated greater self-efficacy. Internal reliability was good at all assessments (alphas of .89 to .93).

Pain-related interference with functioning was assessed with AIMS2 subscales relevant to lower extremity functioning [43] including mobility level (5 items), walking and bending (5 items), self-care (4 items), and household tasks (4 items). Responses for mobility level and walking and bending were provided on a scale from 1 (no days) to 5 (all days) and responses for self-care and household tasks were provided on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). They were recoded as necessary then summed and normalized to produce possible scores ranging from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating worse functioning. Internal reliability was good at all assessments (alphas of .84 to .86).

Pain-related anxiety was assessed with the 20-item Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale [47], which measures fear of pain, cognitive anxiety, avoidance, and physiological symptoms of anxiety on a scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). Responses were summed so that higher scores indicated greater anxiety. Internal reliability was good (α=.92, all assessments).

Positive and negative affect was assessed with the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Scale [68], which assesses positive (10 items) and negative affect (10 items) during the past few weeks on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Responses for each subscale were summed so that higher scores indicated greater positive or negative affect. Internal reliability was good at all assessments (alphas of .87 to .89 for positive affect, alphas of .81 to .90 for negative affect).

Sociodemographics were self-reported and included participant sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, work status, and annual household income.

Medical variables included self-reported medical co-morbidities assessed with the AIMS2 comorbidities subscale [49], which asks respondents whether their health is currently affected by 11 medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, cancer). We added three conditions (vision problems, hearing problems, and arthritis of the hand or wrist) that may affect completion of PainCOACH. Conditions endorsed as being present were summed to yield a score from 0 to 14.

Retention plan

All participants were phoned to remind them of study appointments. Additionally, because many participants had little experience using computers, participants randomized to the PainCOACH treatment condition were phoned by a trained staff member several days after baseline to verify they had been able to connect their tablet computer to the Internet and log on to the program. In addition, participants received a brief phone call to encourage continued use of the program and to resolve questions or problems that could be hindering program use if they: (1) did not sign into the first PainCOACH module within 10 days of joining the study or (2) did not sign into the next scheduled module within 10 days of completing the prior module. Of the 58 participants in the PainCOACH condition, 43.1% needed no prompts to log in, 34.5% needed one prompt, 12.1% needed two prompts, and 10.3% needed three or more prompts.

Power

This small-scale trial was not intended to have statistical power to test the efficacy of the PainCOACH program, but rather to evaluate the intervention’s potential for efficacy and its acceptability. Consistent with recommendations for conducting pilot studies to inform larger trials [60], the sample size was selected to yield precise parameter estimates, including effect sizes (e.g., to inform later sample size estimation). Consequently, we report Cohen’s d effect sizes for analyses evaluating potential efficacy regardless of the significance of the mixed models. In general, a Cohen’s d of ≤ .20 is considered to be a small effect, .50 is considered to be a medium effect, and ≥ .80 is considered to be a large effect [12].

Statistical analysis plan

Analyses focused on evaluating the potential efficacy of the PainCOACH program (as indicated by its effects on primary and secondary outcomes) and its acceptability. Potential efficacy (i.e., effects on primary and secondary outcomes at post-intervention) was evaluated with linear mixed models using V. 9.2 of the SAS procedure MIXED. Before beginning these analyses, the distribution and psychometric properties of all measures were evaluated and the success of randomization was evaluated with bivariate analyses examining whether the PainCOACH and control groups differed with respect to sociodemographic variables, medical variables, or study outcomes. As a first step, initial models for each outcome examined changes in the outcome over time. Second, any covariates identified as having an effect on the outcome being evaluated (p≤ 0.25) were added to the models. For these analyses, some covariates were represented by dummy-coded variables, including sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White vs. other), marital status (married/partnered vs. other), education (4-year college degree or higher education vs. other), and work status (working full-/part-time vs. other). Third, the main effect for treatment condition (PainCOACH vs. control) was evaluated, followed by the interaction of time by treatment condition. Finally, the interaction of sex by treatment condition was evaluated to examine sex differences in responses to the intervention. Analyses used an “Intent to Treat” approach because the statistical procedures used all information participants provided even if some of it was missing. As a consequence, all 113 participants were included in all analyses.

Analyses evaluating the acceptability of pain coping skills training to this population used descriptive statistics to examine retention, adherence (completion of PainCOACH modules), and participants’ use of program features.

Results

Table 2 shows the baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the 113 participants. The sample was mostly female and married, with an average age of 67 years (range 38 to 90). Thirty-one percent were from racial/ethnic minority groups other than non-Hispanic White. Annual household income ranged from less than $15,000 to greater than $135,000; however, the median fell below the United States 2012 median household income of $51,017 [16]. Educational attainment also varied substantially; 30% of the sample had a high school education or less and 39% had a four-year college degree or more. Most participants had both hip and knee OA. Participants in the two treatment conditions did not differ at baseline in terms of sociodemographic, medical, or study outcome variables.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of sample

| Variable | PainCOACH (n=58) |

Assessment Only (n=55) |

Total (n=113) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 68.52 (7.65) | 66.67 (11.02) | 67.62 (9.45) |

| Sex (n) | |||

| Female | 46 (79%) | 45 (82%) | 91 (81%) |

| Male | 12 (21%) | 10 (18%) | 22 (19%) |

| Ethnicity (n) | |||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 51 (88%) | 50 (91%) | 101 (89%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 7 (12%) | 5 (9%) | 12 (11%) |

| Race (n) | |||

| White | 38 (66%) | 41 (75%) | 79 (70%) |

| African American/Black | 20 (35%) | 13 (24%) | 33 (29%) |

| Other race | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Marital status (n) | |||

| Married/partnered | 36 (62%) | 34 (62%) | 70 (62%) |

| Widowed | 12 (21%) | 11 (20%) | 23 (20%) |

| Single/divorced/separated | 10 (18%) | 10 (19%) | 20 (18%) |

| Work status (n) | |||

| Retired | 34 (59%) | 34 (62%) | 68 (60%) |

| Working full-/part-time | 13 (22%) | 11 (20%) | 24 (21%) |

| Other | 11 (19%) | 10 (17%) | 21 (19%) |

| Highest education level completed (n) | |||

| Less than high school | 4 (7%) | 4 (7%) | 8 (7%) |

| High school | 13 (22%) | 13 (24%) | 26 (23%) |

| Partial college/trade school | 17 (29%) | 19 (35%) | 36 (32%) |

| 4-year college education | 17 (29%) | 13 (24%) | 30 (27%) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 7 (12%) | 6 (11%) | 13 (12%) |

| Annual household income (Median) | $30,000-$44,999 | $30,000-$44,999 | $30,000-$44,999 |

| Medical comorbidities (number) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.34 (1.02) | 1.31 (1.05) | 1.33 (1.03) |

| Osteoarthritis (n) | |||

| Knee | 18 (33%) | 22 (38%) | 40 (35%) |

| Hip | 9 (16%) | 5 (9%) | 14 (12%) |

| Both | 28 (51%) | 31 (53%) | 59 (52%) |

Note: Percentages for some variables do not sum to 100% due to rounding. Participants randomly assigned to the two study groups do not differ significantly on any listed variables.

PainCOACH potential efficacy

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics for all outcome variables by treatment condition and time of assessment. Analyses examining the potential efficacy of PainCOACH (as indicated by its effects on primary and secondary outcomes) are described below. Although we report significance levels, this study was not designed to provide sufficient statistical power to detect expected effects. Effect sizes are therefore reported to evaluate potential efficacy.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for primary and secondary outcomes by treatment condition over time

| PainCOACH |

Assessment Only |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Men (n=12) Mean (SD) |

Women (n=46) Mean (SD) |

Total (n=58) Mean (SD) |

Men (n=10) Mean (SD) |

Women (n=45) Mean (SD) |

Total (n=55) Mean (SD) |

| Pain | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.79 (1.71) | 4.82 (1.75) | 4.82 (1.73) | 3.60 (1.26) | 5.46 (1.74) | 5.12 (1.81) |

| Midpoint | 4.41 (1.92) | 4.14 (1.63) | 4.20 (1.68) | 2.65 (1.20) | 5.23 (1.92) | 4.75 (2.07) |

| Post-intervention | 4.13 (2.32) | 4.06 (1.92) | 4.07 (1.99) | 3.50 (1.92) | 4.85 (1.69) | 4.62 (1.79) |

| Pain-related functioning | ||||||

| Baseline | 1.23 (.96) | 1.82 (1.36) | 1.70 (1.30) | 1.69 (1.09) | 1.94 (1.02) | 1.89 (1.03) |

| Midpoint | 1.78 (1.36) | 1.73 (1.24) | 1.74 (1.25) | 1.26 (1.06) | 1.94 (1.07) | 1.82 (1.09) |

| Post-intervention | 1.18 (.79) | 1.73 (1.25) | 1.62 (1.19) | 1.28 (1.19) | 1.85 (1.24) | 1.75 (1.24) |

| Pain anxiety | ||||||

| Baseline | 19.00 (14.21) | 28.83 (20.68) | 26.79 (19.81) | 32.70 (22.54) | 29.36 (17.35) | 29.97 (18.21) |

| Midpoint | 25.27 (15.99) | 28.33 (19.36) | 27.73 (18.65) | 27.30 (17.18) | 31.20 (17.90) | 30.48 (17.68) |

| Post-intervention | 23.35 (20.23) | 23.18 (16.67) | 23.21 (17.29) | 29.56 (16.09) | 26.93 (17.41) | 27.39 (17.06) |

| Negative affect | ||||||

| Baseline | 10.00 (6.12) | 9.85 (6.55) | 9.88 (6.41) | 9.50 (5.78) | 9.83 (7.20) | 9.77 (6.92) |

| Midpoint | 9.45 (5.28) | 9.02 (6.67) | 9.11 (6.38) | 8.90 (6.24) | 9.23 (8.87) | 9.17 (8.39) |

| Post-intervention | 8.92 (6.60) | 8.00 (6.23) | 8.20 (6.26) | 9.44 (4.80) | 8.79 (9.24) | 8.90 (8.60) |

| Positive affect | ||||||

| Baseline | 37.42 (7.39) | 35.18 (8.11) | 35.64 (7.95) | 32.40 (10.72) | 36.05 (7.45) | 35.39 (8.15) |

| Midpoint | 34.27 (7.64) | 36.61 (7.08) | 36.15 (7.18) | 31.10 (10.10) | 33.79 (8.88) | 33.29 (9.08) |

| Post-intervention | 38.17 (8.60) | 35.84 (8.70) | 36.34 (8.65) | 31.33 (9.76) | 34.88 (10.26) | 34.27 (10.17) |

| Self-efficacy | ||||||

| Baseline | 7.06 (1.64) | 6.55 (1.85) | 6.66 (1.81) | 6.06 (2.10) | 6.38 (2.09) | 6.32 (2.08) |

| Midpoint | 7.31 (1.24) | 7.18 (1.94) | 7.20 (1.81) | 6.35 (2.06) | 6.39 (1.98) | 6.38 (1.97) |

| Post-intervention | 7.66 (1.70) | 7.53 (2.09) | 7.56 (2.00) | 7.31 (1.59) | 6.53 (2.10) | 6.67 (2.02) |

Note: Table shows unadjusted means and standard deviations.

Pain

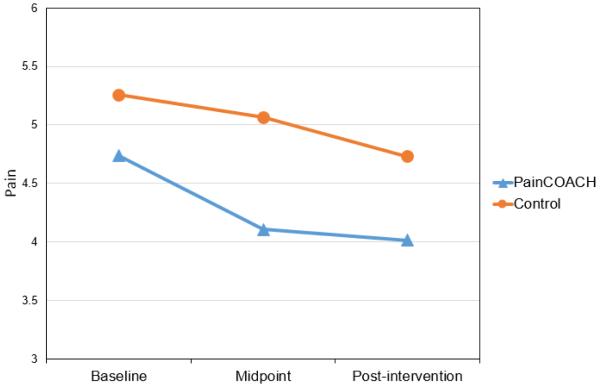

Based on the criterion described in the statistical analysis plan, the covariates for this outcome were age, sex, and work status. Results showed a significant sex by treatment interaction, F(1,107)=12.96; p<.001. This finding led us to test a linear mixed model that included women only, retaining age and work status as covariates. (A similar model for men was not tested because of the small number of men in the study). Results revealed effects of time, F(2,88)=8.25, p=.001, and treatment condition F(1,88)=4.99, p=.028, but their interaction did not reach significance, F(2,88)=0.93, p=.40. Examination of adjusted means (see Figure 2) showed that women in the PainCOACH and control conditions did not differ in mean pain at baseline, Tukey adjusted p=.692. However, women in the PainCOACH condition had significant reductions in pain from baseline (M=4.74) to midpoint (M=4.11; Tukey adjusted p=.028) and from baseline to post-intervention (M=4.02; Tukey adjusted p=.036). The main effect of treatment and pattern of means indicated that positive effects of the intervention on pain occurred between baseline and midpoint and were maintained through post-intervention. There were not corresponding significant reductions in pain for women in the control condition (Ms=5.26, 5.06, and 4.73 for baseline, midpoint, and post-intervention, respectively), although change from baseline to post-intervention was marginally significant (Tukey adjusted p=.09). The Cohen’s d effect size [12] for the group difference at post-intervention was .33.

Fig. 2.

Pain scores at baseline, midpoint, and post-intervention by randomized study condition

Self-efficacy

The only covariate for this outcome was number of medical comorbidities. There was a significant effect of treatment such that participants in the PainCOACH condition (M=7.11) reported significantly higher levels of self-efficacy than participants in the control condition (M=6.49; Tukey adjusted p=.038). The time by treatment interaction was not significant, F(2,110) = .95, p=.388. Thus, collapsing across time, PainCOACH participants had higher self-efficacy for pain management. Examination of adjusted means showed that there was no group difference in self-efficacy at baseline (Tukey adjusted p=.925), indicating that group differences in self-efficacy emerged after the baseline assessment. Furthermore, in the control group, self-efficacy did not change over time (Ms=6.31, 6.39, and 6.70 for baseline, midpoint, and post-intervention, respectively). In contrast, in the PainCOACH group, self-efficacy increased significantly from baseline (M=6.66) to post-intervention (M=7.52; Tukey adjusted p=.023), although increases from baseline to midpoint (M=7.21) and from midpoint to post-intervention did not reach significance (Tukey adjusted ps=.193 and .650, respectively). Taken together, the main effect of treatment and pattern of means indicated that positive effects of the intervention on self-efficacy occurred between baseline and midpoint and were maintained through post-intervention. The Cohen’s d effect size [12] for the group difference at post-intervention was .43.

Pain-related interference with functioning

Covariates for this outcome included sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, and number of medical comorbidities. There was no significant effect of treatment, F(1,102)=1.55, p=.216. Furthermore, the time by treatment interaction was not significant, F(2,207)=.06, p=.9376, nor were any interactions between the covariates and treatment condition. The Cohen’s d effect size [12] for the group difference at post-intervention was .13.

Pain anxiety

The covariates for this outcome included race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, and number of medical comorbidities. The effect of treatment was not significant, F(1,102)=1.55, p=.216, nor was the time by treatment interaction, F(2,207)=.06, p=.938. The Cohen’s d effect size [12] for the group difference at post-intervention was .20.

Negative Affect

No covariates were required for this outcome. There was no significant effect of treatment, F(1,111)=.05, p=.820. Furthermore, the time by treatment interaction was not significant, F(2,214)=.23, p=.796. The Cohen’s d effect size [12] for the group difference at post-intervention was .10.

Positive Affect

The covariates for this outcome included sex and education. The main effect for treatment was not significant, F(1,109) = 1.42, p=.236; however, there was a marginally significant time by treatment interaction, F(2,214) = 2.53, p=.082. Examination of the adjusted means suggested that positive affect increased among participants in the PainCOACH condition from baseline to midpoint and post-intervention (Ms=35.51, 36.15, and 36.30, respectively) whereas this pattern was not observed among participants in the control condition (Ms=35.49, 33.40, and 34.17, respectively). However, these differences were not significant using a Tukey adjusted p value. The Cohen’s d effect size for the group difference at post-intervention was .24.

We note that the foregoing analyses did not reveal any findings that would indicate concerns about the safety of the intervention. Likewise, no adverse events occurred that were related to completion of the PainCOACH program.

PainCOACH acceptability

Of 113 participants randomized, 97% (n=110) completed the midpoint assessment and 96% (n=109) completed the post-intervention assessment. Attrition was 5% (n=3) in the control group and 2% (n=1) in the PainCOACH group. Among PainCOACH participants, adherence to the program was high: 53 of the 58 (91%) completed all eight training modules.

Many participants used resources provided in PainCOACH to increase engagement and learning: most used the workbook to take notes (85.5%) or complete worksheets (79.6%); 81.8% read other people’s stories in COACHchat, and 25.5% shared their own stories; over half used COACHtrack to log practices (54.5%), view their progress in practices and/or self-efficacy (65.5%), change their practice goals (68.5%), manage automated practice reminders (56.4%), and record their self-efficacy (51.9%).

Discussion

This early-stage trial evaluated PCST delivered via an automated Internet intervention called PainCOACH. Results generally supported the program’s promise among people with hip and/or knee OA. Overall, effect sizes ranged from trivial to medium across outcomes, with the most notable effects on pain and self-efficacy for pain management. Specifically, women who used PainCOACH reported lower pain than women in the control group, with an effect size in a range considered to be clinically significant [55; 61]. Additionally, PainCOACH users’ self-efficacy for pain management increased from baseline to post-intervention compared to the control group, suggesting potential for sustained benefits. These findings, along with strong evidence for the program’s acceptability, highlight the clinical promise of delivering PCST via the Internet and support continued development and evaluation of the PainCOACH program to strengthen its effects.

These findings were especially encouraging in light of the fact that participants were a racially diverse sample of older adults, some with low income, living in a rural area, and/or with little experience using computers or the Internet. Although some investigators may have concerns about using a technology-based intervention in a population like this, the number of older adults accessing the Internet is growing steadily [69] and evidence supports the general acceptability of Internet-based interventions among older adults [13; 48].

Indeed, at baseline 50% of our participants expressed a preference for learning pain coping skills at home on a computer and adherence to PainCOACH was very high: 91% of participants who began PainCOACH completed all eight modules. This finding offers a striking contrast with high rates of non-adherence observed for many other behavioral Internet interventions [see 18]. A recent review of Internet-based behavioral health promotion interventions found average adherence of about 50% [34], and a study investigating an Internet-based physical activity intervention for people with hip or knee OA found that only 19% completed all nine intervention modules and 46% completed six modules (defined as adequate adherence) [8].

A variety of factors may have contributed to our high adherence. First, at baseline we used motivational interviewing techniques to enhance motivation to complete PainCOACH. Second, the program was designed to simulate features of in-person PCST that make it engaging and effective [57], including the sense of being understood within a responsive, empathetic relationship with a therapist. For instance, carefully crafted tailoring algorithms and wording were used to ensure that PainCOACH’s virtual coach presented information and responded to participants’ actions in a manner consistent with how a trained, expert therapist would do these things in person. Third, the program was designed to engage a sense of accountability [51]. For instance, the virtual coach engaged participants in interactive exercises that mimicked social interactions about important intervention activities (e.g., verifying appointments for completing subsequent modules). Fourth, we used an iterative development process to gather extensive feedback from our target audience to enhance the program’s usability and content [57]. Further research will be needed to determine the extent to which these or other factors or others contributed to the unusually high adherence observed in this study.

Yet it is also the case that 23% of our potential participants declined screening because they did not want to use a computer. This finding underscores the fact that programs such as PainCOACH should not be viewed as supplanting in-person training, but rather as supplementing it by increasing access and offering an Internet-based alternative to people who prefer it. Yet, there may be ways to increase older adults’ interest in trying Internet interventions even when they have concerns about using computers. For instance, they may be persuaded to try these programs if peers suggest and model their use. Furthermore, positive initial experiences with an easy-to-use Internet intervention may address some concerns about using computers and encourage continued use. In fact, preference for completing PCST on a computer increased from 50% at baseline to 62% post-intervention among participants who used PainCOACH.

Findings from this study will be used to refine PainCOACH, with the goal of enhancing its efficacy. For instance, although large percentages of participants used PainCOACH resources such as COACHchat and COACHtrack, the lowest usage was for features intended to remind participants to practice skills and to self-monitor their practices and program benefits. Improving these features to increase their use should enhance the program’s efficacy [e.g., 35; 44].

We will also refine study protocols to improve our ability to evaluate the program’s efficacy. For instance, we could not adequately evaluate reduction in pain among men; they had significantly lower pain than women at entry into the study, especially if they were in the control group. Accordingly, we do not believe our findings indicate that PainCOACH should only be tested among women in the future. PCST has been found to be effective in samples that include both men and women [24; 29], and although women report greater OA pain than men [66], millions of men are burdened by OA pain. Our planned larger-scale trial will use more rigorous screening to ensure participants have sufficiently high pain to require intervention, especially in light of the fact that our participants’ baseline pain scores (even women’s) were somewhat lower than those reported in other OA interventions [e.g., 2; 63; 64], limiting our ability to detect improvements in pain.

Several other effects were smaller than expected. For instance, effects on pain-related interference with functioning were trivial. However, our participants’ pain-related interference with functioning at baseline was low (a mean of 1.79 on a possible scale from 0-10, with lower scores indicating better functioning). Thus, on average, our participants had little pain-related impairment when they entered the study and little room for improvement. A more rigorous test will require testing PainCOACH in a sample with greater impairment. Similarly, the program’s trivial effect on negative affect was unexpected, but low average levels of negative affect at baseline (a mean of less than 10 out of a possible score of 50) likely limited our ability to evaluate effects on this outcome. Effects on positive affect were stronger, albeit still small. Although not as well-studied as negative affect, this finding is interesting given growing evidence linking positive affect with adaptive cognitive, behavioral, and emotional processes [11; 20; 41].

One limitation of the study is that it lacked an attention control group. A key distinction has been made between control and comparison functions of control groups [21]. In the present study, the assessment only control group (in conjunction with rigorous methods) controlled for alternative causal explanations for study findings. It was therefore useful for evaluating internal validity in this early-stage trial. Moreover, our control group’s OA treatments were not constrained or enhanced in any way, so the group’s outcomes should reflect those that may occur in a community setting without access to PainCOACH. Nonetheless, a worthy goal for future work will be to use an active comparison group to evaluate effects of theorized therapeutically-active components of PainCOACH and to rule out attention and expectancy factors (e.g., a group that receives Internet-based education about OA and its treatment) [56].

A second limitation of the study is that it did not include equal numbers of men and women, precluding planned examination of sex differences. More women than men were available for recruitment in our pools of potential participants, and more men than women declined to join the study. Prior to conducting a larger-scale trial, it will be necessary to ensure the refined program and study protocol address the needs of both men and women.

Despite these limitations, this study also made strong contributions. First, PainCOACH is the only Internet-based behavioral pain intervention that we know of to focus specifically on OA pain with an automated approach designed to increase its scalability and cost-effectiveness [cf., 7]. Second, findings demonstrated the potential for an automated, Internet-based intervention to produce benefits despite involving no contact with a therapist. Third, PainCOACH’s potential scalability and cost-effectiveness should make it easier to implement in clinical settings than in-person training, supporting increased clinical use of an empirically-based non-pharmacological pain therapy. Fourth, these benefits occurred in a racially diverse sample of older adults, including many low income individuals and those living in a rural area, suggesting that PainCOACH could reach people whose access to interventions is currently limited. Fifth, adherence to this automated program was exceptionally high, suggesting that participants valued their experience with the program and found it engaging. This is especially notable given that many of our participants had little prior experience with computers or the Internet. The contributions came from a study using an initial version of PainCOACH, which will now be refined to make it more efficacious prior to evaluating it in a larger-scale trial. Some important unanswered questions to address in the future include: 1) What are longer-term effects of the intervention?; 2) Can the number of PainCOACH modules be reduced without sacrificing efficacy?; 3) How can use of the program’s features (e.g., COACHtrack) be improved?; 4) What is the best way to integrate the program into clinical care?; and 5) Does the program’s impact differ by participant sex?

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the people who participated in this study and study staff at the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project and Duke University Medical Center for their assistance. We extend special thanks to Ariana Katz, MPH, for assistance with this article and Susan Kirtz, MPH, for her assistance developing the PainCOACH workbook. PainCOACH was developed by Triad Interactive, Inc., Washington, DC. This research was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number R01 AR057346. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, from which some participants in this trial were derived, is supported in part by cooperative agreements S043, S1734, and S3486 from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention/Association of Schools of Public Health; the NIAMS Multipurpose Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Disease Center grant 5-P60-AR30701; and the NIAMS Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center grants -5 P60 AR49465 and P60-AR064166.

Footnotes

Disclosures: (1) Christine Rini: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past), a financial relationship in the form of employment at UNC-Chapel Hill (paid to her/ongoing), grants pending, and receiving travel/accommodations/meeting expenses related to NIH grant review; (2) Laura S. Porter: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past); (3) Tamara J. Somers: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past) ; (4) Daphne C. McKee: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past); (5) Robert F. DeVellis: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past) ; (6) Meredith Smith: reported a financial relationship in the form of employment at EMG Serono, Inc. (paid to her/current) and ownership of stock in BMS, AbbVie, and Abbott Labs (current); (7) Gary Winkel: reports payment for consulting fee/honorarium (ongoing), fees for participation in review activities (ongoing), and payment for writing or reviewing the manuscript (ongoing); (8) David K. Ahern: reported payment in the form of a consulting fee or honorarium from UNC-Chapel Hill (paid to him/past); (9) Roberta Goldman: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (paid to her as a consultant/past) and a financial relationship in the form of employment with Memorial Hospital of RI (paid her her/ongoing); (10) Jamie L. Stiller: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past) and a financial relationship involving employment at UNC-Chapel Hill (paid to her/current) ; (11) Cara Mariani: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past) and financial relationships consisting of employment at Duke (to institution, past) ; (12) Carol Patterson: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past) and a financial relationship involving employment at UNC-Chapel Hill (paid to her/current); (13) Joanne M. Jordan: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution/past) and financial relationships including a consultancy (Samumed/paid to her/current) and grants pending (paid to institution); (14) David S. Caldwell: reports payment from the grant supporting this work (institution); (15) Francis J. Keefe: nothing to report.

The authors of this paper do not have any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- [1].Affleck G, Tennen H, Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Kashikar-Zuck S, Wright K, Starr K, Caldwell DS. Everyday life with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis: independent effects of disease and gender on daily pain, mood, and coping. Pain. 1999;83(3):601–609. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Allen KD, Helmick CG, Schwartz TA, DeVellis RF, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Racial differences in self-reported pain and function among individuals with radiographic hip and knee osteoarthritis: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(9):1132–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Brown C, Cooke TD, Daniel W, Feldman D, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(5):505–514. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum-Us. 1986;29(8):1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company.; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Beatty L, Lambert S. A systematic review of internet-based self-help therapeutic interventions to improve distress and disease-control among adults with chronic health conditions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(4):609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bossen D, Veenhof C, Van Beek KE, Spreeuwenberg PM, Dekker J, De Bakker DH. Effectiveness of a web-based physical activity intervention in patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(11):e257. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40(9):771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, Bradley KA, Nugent SM, Baines AD, VanRyn M. Validation of Screening Questions for Limited Health Literacy in a Large VA Outpatient Population. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(5):561–566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive Psychological Well-Being and Mortality: A Quantitative Review of Prospective Observational Studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(7):741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Crabb RM, Rafie S, Weingardt KR. Health-Related Internet Use in Older Primary Care Patients. Gerontology. 2012;58(2):164–170. doi: 10.1159/000329340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, Bridgett L, Williams S, Guillemin F, Hill CL, Laslett LL, Jones G, Cicuttini F, Osborne R, Vos T, Buchbinder R, Woolf A, March L. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323–1330. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cuijpers P, Straten A, Andersson G. Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: a systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;31(2):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2012. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Devos-Comby L, Cronan T, Roesch SC. Do exercise and self-management interventions benefit patients with osteoarthritis of the knee? A metaanalytic review. The Journal of rheumatology. 2006;33(4):744–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(1):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL., 3rd Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2009;10(5):447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fredrickson BL, Branigan C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion. 2005;19(3):313–332. doi: 10.1080/02699930441000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Freedland KE, Mohr DC, Davidson KW, Schwartz JE. Usual and Unusual Care. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73(4):323–335. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318218e1fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gunter RW, Whittal ML. Dissemination of cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders: Overcoming barriers and improving patient access. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hootman JM, Helmick CG. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum-Us. 2006;54(1):226–229. doi: 10.1002/art.21562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hunt MA, Keefe FJ, Bryant C, Metcalf BR, Ahamed Y, Nicholas MK, Bennell KL. A physiotherapist-delivered, combined exercise and pain coping skills training intervention for individuals with knee osteoarthritis: A pilot study. The Knee. 2013;20(2):106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Iversen MD, Hammond A, Betteridge N. Self-management of rheumatic diseases: state of the art and future perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):955–963. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.129270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jordan JM, Linder GF, Renner JB, Fryer JG. The impact of arthritis in rural populations. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8(4):242–250. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Keefe FJ, Affleck G, France CR, Emery CF, Waters S, Caldwell DS, Stainbrook D, Hackshaw KV, Fox LC, Wilson K. Gender differences in pain, coping, and mood in individuals having osteoarthritic knee pain: a within-day analysis. Pain. 2004;110(3):571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Keefe FJ, Beaupre PM, Gil KM, Rumble ME, Aspnes AK. Group therapy for patients with chronic pain. In: Turk DC, Gatchel RJ, editors. Pain management: A practitioner’s handbook. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. pp. 234–255. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Keefe FJ, Blumenthal J, Baucom D, Affleck G, Waugh R, Caldwell DS, Beaupre P, Kashikar-Zuck S, Wright K, Egert J, Lefebvre J. Effects of spouse-assisted coping skills training and exercise training in patients with osteoarthritic knee pain: a randomized controlled study. Pain. 2004;110(3):539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Williams DA, Gil KM, Mitchell D, Robertson C, Martinez S, Nunley J, Beckham JC, Crisson JE, Helms M. Pain Coping Skills Training in the Management of Osteoarthritic Knee Pain - a Comparative-Study. Behav Ther. 1990;21(1):49–62. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Williams DA, Gil KM, Mitchell D, Robertson C, Martinez S, Nunley J, Beckham JC, Helms M. Pain Coping Skills Training in the Management of Osteoarthritic Knee Pain-II - Follow-up Results. Behav Ther. 1990;21(4):435–447. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Egert JR, Affleck G, Sullivan MJ, Caldwell DS. The relationship of gender to pain, pain behavior, and disability in osteoarthritis patients: the role of catastrophizing. Pain. 2000;87(3):325–334. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Keefe FJ, Somers TJ. Psychological approaches to understanding and treating arthritis pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(4):210–216. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, Van Gemert-Pijnen JEWC. Persuasive System Design Does Matter: A Systematic Review of Adherence to Web-Based Interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(6):17–40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kennedy CM, Powell J, Payne TH, Ainsworth J, Boyd A, Buchan I. Active Assistance Technology for Health-Related Behavior Change: An Interdisciplinary Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(3):e80. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Knowles MS. The adult learner: A neglected species. Gulf Pub. Co.; Houston: 1984. Book Division. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Elsevier; Boston: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kroon FP, van der Burg LR, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Johnston RV, Pitt V. Self-management education programmes for osteoarthritis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;1:CD008963. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008963.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Jordan JM, Katz JN, Kremers HM, Wolfe F. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman HR. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum-Us. 1989;32(1):37–44. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Macea DD, Gajos K, Daglia Calil YA, Fregni F. The efficacy of Web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2010;11(10):917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. A model of health status for rheumatoid arthritis. A factor analysis of the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales. Arthritis Rheum-Us. 1988;31(6):714–720. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mausbach BT, Moore R, Roesch S, Cardenas V, Patterson TL. The Relationship Between Homework Compliance and Therapy Outcomes: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34(5):429–438. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9297-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].May S. Self-management of chronic low back pain and osteoarthritis. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2010;6(4):199–209. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mayer RE. Applying the science of learning: evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. Am Psychol. 2008;63(8):760–769. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.8.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].McCracken LM, Dhingra L. A short version of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-20): preliminary development and validity. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7(1):45–50. doi: 10.1155/2002/517163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].McMurchie W, Macleod F, Power K, Laidlaw K, Prentice N. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety with older people: a pilot study to examine patient acceptability and treatment outcome. Int J Geriatr Psych. 2013 doi: 10.1002/gps.3935. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Guccione AA, Kazis LE. Aims2 - the Content and Properties of a Revised and Expanded Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales Health-Status Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum-Us. 1992;35(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. Guilford Press; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, Lehman K. Supportive Accountability: A Model for Providing Human Support to Enhance Adherence to eHealth Interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13(1):e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Murray E, White IR, Varagunam M, Godfrey C, Khadjesari Z, McCambridge J. Attrition revisited: adherence and retention in a web-based alcohol trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(8):e162. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Racine M, Tousignant-Laflamme Y, Kloda LA, Dion D, Dupuis G, Choiniere M. A systematic literature review of 10 years of research on sex/gender and pain perception - part 2: do biopsychosocial factors alter pain sensitivity differently in women and men? Pain. 2012;153(3):619–635. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Revicki DA, Cella D, Hays RD, Sloan JA, Lenderking WR, Aaronson NK. Responsiveness and minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes. Health Qual Life Out. 2006;4(1):70. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Riddle DL, Keefe FJ, Ang D, Dumenci L, Jensen MP, Bair MJ, Reed SD, Kroenke K. A phase III randomized three-arm trial of physical therapist delivered pain coping skills training for patients with total knee arthroplasty: the KASTPain protocol. Bmc Musculoskel Dis. 2012;13(1):149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-149. J K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Rini C, Porter LS, Somers TJ, McKee DC, Keefe FJ. Retaining critical therapeutic elements of behavioral interventions translated for delivery via the Internet: Recommendations and an example using pain coping skills training. JMIR. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3374. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rini C, Williams DA, Broderick JE, Keefe FJ. Meeting Them Where They Are: Using the Internet to Deliver Behavioral Medicine Interventions for Pain. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(1):82–92. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0107-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Shafran R, Clark DM, Fairburn CG, Arntz A, Barlow DH, Ehlers A, Freeston M, Garety PA, Hollon SD, Ost LG, Salkovskis PM, Williams JM, Wilson GT. Mind the gap: Improving the dissemination of CBT. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(11):902–909. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Sim J, Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Sloan JA, Cella D, Hays RD. Clinical significance of patient-reported questionnaire data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:1217–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Smith SJ, Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Romano J, Baucom D. Gender differences in patient-spouse interactions: a sequential analysis of behavioral interactions in patients having osteoarthritic knee pain. Pain. 2004;112(1-2):183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Somers TJ, Blumenthal JA, Guilak F, Kraus VB, Schmitt DO, Babyak MA, Craighead LW, Caldwell DS, Rice JR, McKee DC, Shelby RA, Campbell LC, Pells JJ, Sims EL, Queen R, Carson JW, Connelly M, Dixon KE, LaCaille LJ, Huebner JL, Rejeski WJ, Keefe FJ. Pain coping skills training and lifestyle behavioral weight management in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled study. Pain. 2012;153(6):1199–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sperber NR, Bosworth HB, Coffman CJ, Lindquist JH, Oddone EZ, Weinberger M, Allen KD. Differences in osteoarthritis self-management support intervention outcomes according to race and health literacy. Health Education Research. 2013;28(3):502–511. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Strecher V. Internet methods for delivering behavioral and health-related interventions (eHealth) Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:53–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Theis KA, Helmick CG, Hootman JM. Arthritis burden and impact are greater among U.S. women than men: intervention opportunities. Journal of women's health. 2007;16(4):441–453. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Unruh AM. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain. 1996;65(2-3):123–167. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Zickuhr K, Madden M. Older adults and Internet use: Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project. 2012 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.