Abstract

The four known ID proteins (ID1-4, Inhibitor of Differentiation) share a homologous helix loop helix (HLH) domain and act as dominant negative regulators of basic-HLH transcription factors. ID proteins also interact with many non-bHLH proteins in complex networks. The expression of ID proteins is increasingly observed in many cancers. Whereas ID-1, ID-2 and ID-3, are generally considered as tumor promoters, ID4 on the contrary has emerged as a tumor suppressor. In this study we demonstrate that ID4 heterodimerizes with ID-1, -2 and -3 and promote bHLH DNA binding, essentially acting as an inhibitor of inhibitors of differentiation proteins. Interaction of ID4 was observed with ID1, ID2 and ID3 that was dependent on intact HLH domain of ID4. Interaction with bHLH protein E47 required almost 3 fold higher concentration of ID4 as compared to ID1. Furthermore, inhibition of E47 DNA binding by ID1 was restored by ID4 in an EMSA binding assay. ID4 and ID1 were also colocalized in prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. The alpha helix forming alanine stretch N-terminal, unique to HLH ID4 domain was required for optimum interaction. Ectopic expression of ID4 in DU145 prostate cancer line promoted E47 dependent expression of CDKNI p21. Thus counteracting the biological activities of ID-1, -2 and -3 by forming inactive heterodimers appears to be a novel mechanism of action of ID4. These results could have far reaching consequences in developing strategies to target ID proteins for cancer therapy and understanding biologically relevant ID- interactions.

Keywords: DNA-protein interaction, protein-protein interaction, tumor suppressor gene, cancer, ID4

1. INTRODUCTION

The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of transcription factors are critical cell type determinants that play important roles in cellular differentiation 1. The highly conserved bHLH domain (reviewed in 2,3 consists of two amphipathic helices separated by a loop that mediates homo and hetero- dimerization adjacent to a DNA-binding region rich in basic amino acids 4. The bHLH dimers bind to an E-Box (CANNTG) DNA consensus sequence present in a wide variety of tissue-specific promoters 5. The transcriptionally active bHLH dimer usually consists of heterodimers between class I proteins E2–2 6, HEB 7, and E12 and E47 (i.e. differentially spliced products of the E2A gene 8) and tissue restricted class II proteins such as MyoD 9 and NeuroD 10. The members of class V, the ID (inhibitor of differentiation/DNA binding) family regulate the transcriptional activity of class I and II bHLH heterodimers. The four known ID proteins (ID1, ID2, ID3, and ID4) share a homologous HLH domain, but lack the basic DNA binding region 11. Thus, the ID proteins sequester bHLH transcription factors by forming inactive heterodimers and prevent binding of bHLH proteins to the E-box responsive elements 12,13. Therefore, ID proteins are largely considered as dominant negative regulators of differentiation pathways but positive regulators of cellular proliferation 13–15. Apart from bHLH proteins, the ID proteins also interact with many non-bHLH proteins with different affinities 16–19 in complex transcriptional and non-transcriptional networks.

As key regulators of cell cycle and differentiation, the expression of ID proteins is increasingly observed in many cancers and in most cases associated with aggressiveness of the disease including poor prognosis 20–23, metastasis 24 and angiogenesis 25. ID1, ID2 and ID3, are thus generally considered as tumor promoters/supporting oncogenes. On the contrary ID4 has emerged as a tumor suppressor 26–33 based on the evidence that it is epigenetically silenced in many cancers 28,29,34,35. In few cancers ID4 also acts as an oncogene such as in Ovarian Cancer 36,37, Malignant rhabdoid tumors 38 and Glioblastoma 39.

The associated molecular pathways and unique expression profile during development suggests that ID4 may have functions distinct from other ID family members 40–43. In vitro studies have also demonstrated that ectopic ID4 expression in cancer cells inhibits proliferation, promotes senescence, apoptosis and sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs44. Thus the biological effect of ID4 appears to be almost completely opposite to those observed by ID-1, -2 and -3 suggesting that the core function of ID proteins as dominant negative bHLH transcriptional regulators may be just a fraction of their overall activity. The majority of ID functions could involve unknown and perhaps yet undefined interactions with sequence specific bHLH or non-bHLH proteins resulting in non-overlapping biological endpoints.

Of all the four ID proteins, the expression of ID1 and ID2 in cancer and the underlying molecular mechanism is relatively well known 45–48. As compared to ID1, ID2 and ID3, the mechanism of action of ID4 remains largely unexplored. Based on the observations that ectopic expression of ID4 in cancer cell lines attenuates the biological pathways promoted by ID-1, -2 and -3, we conceptualized a highly simplistic model in which ID4 could form a heterodimeric complex with ID-1, -2 or -3 and essentially neutralize their dominant negative bHLH activity. In this study we demonstrate that ID4 in fact has the unique ability to heterodimerize with ID-1, -2 and -3 and promote bHLH DNA binding. These results could have far reaching consequences in developing strategies to target ID proteins for cancer therapy and understanding the ID-bHLH and ID-non-bHLH interactions in cell growth and development.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cell Line and Cell culture

Human prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP, DU145 and PC3 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD). LNCaP cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta GA) and antibiotics (pen/strep, Normocin and Gentamycin). DU145 and PC3 cell were cultured in Ham’s F12 (Meditech, VA) supplemented with 5% bovine calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals) and antibiotics (pen/strep, Normocin and Gentamycin). All cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. DU145 cells over-expressing full length human ID4 (DU145+ID4) is described elsewhere49,50.

2.2. Recombinant plasmids

The pReceiver-B04 with GST tagged ID4 (OmicsLink Expression Clone) was obtained from GeneCopeia Inc. The pET28a-His-Id1 and pET30a-His-E47plasmids were kindly provided by Dr. Robert Benezra (Memorial Sloan Kettering Medical Center). The GST-ID2 plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Chuanju Liu (New York University School of Medicine).

2.3. Recombinant Protein expression and purification

The above mentioned bacterial expression plasmids containing affinity tagged ID-1, -2 and -4 were transformed into E. Coli host strain BL21 (DE3). Optimum recombinant protein expression was obtained with 1mM IPTG followed by incubation at 30C for 3–4 hrs. Cells were subsequently harvested by centrifugation at 3000g for 15 min at 40 C. The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (B-PER, Thermo Scientific) supplemented with 1 mg/ml lysozyme, DNase and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Invitrogen). The lysate was then clarified by centrifugation at 14000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was loaded on pre-equilibrated affinity column (Glutathione for GST and Ni-NTA for His tagged proteins) and eluted according to manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo scientific). On-column cleavage of GST tag from ID4 and ID2 was performed by enterokinase (Gene Script) and thrombin (NEB) respectively. The eluted recombinant proteins were dialyzed against 50mM Tris (PH7.2) (Tube-O-Dialyzer Medi, 8kMWCO, G-Biosciences).

2.4. Western blot

Prostate cancer cell lines were lysed using M-PER (Thermo-Scientific). Twenty five microgram of total protein was electrophoretically separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gel and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore). Western blotting was performed according to standard procedures. After incubation with primary and secondary antibodies, the membranes were developed using an ECL kit (GE Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) as described earlier 51. The ID-1, -2, -3, -4 and E47 antibodies used in this study have been validated as described in our previous studies 51–53.

2.5. Immunofluorescence

The cells were grown in six well plates with cover slips. The cells were fixed and permeabilized in methanol for 20 min and then rehydrated with PBS. Before immunostaining with the protein specific antibodies, cells were blocked in 1%BSA in PBS with 0.5% Tween 20. Mouse polyclonal ID4 (Novus), Rabbit polyclonal E47 (Santa Cruz) and Rabbit monoclonal ID1 (BioCheck) antibodies were used for colocalization studies. The primary antibodies were detected by either goat anti-rabbit DyLight 594 or goat anti-mouse Dylight 488 fluorophores (Thermo Scientific). Cells were analyzed using Carl Zeiss AxioVision 4 microscope equipped with AxioCam digital camera and software.

2.6. Coimmunoprecipitation assay

To detect the protein-protein interactions, coimmunoprecipitation was performed using protein A coupled to magnetic beads (Protein A Mag beads, GenScript) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, protein specific IgG (anti-ID1 or -ID4) was first immobilized to Protein A Mag Beads by incubating overnight at 4°C. To minimize the co-elution of IgG following immunoprecipitation, the immobilized IgG on protein A mag beads was cross-linked in the presence of 20mM dimethyl pimelimidate dihydrochloride (DMP) in 0.2M triethanolamine, pH8.2, washed twice in Tris (50mM Tris pH7.5) and PBS followed by final re-suspension and storage in PBS. The cross-linked protein specific IgG-protein A-Mag beads were incubated overnight (4C) with freshly extracted total cellular proteins (500 μg/ml). The complex was then eluted with 0.1 M Glycine (pH 2–3) after appropriate washing with PBS and neutralized by adding neutralization buffer (1 M Tris, pH 8.5) per 100 μl of elution buffer.

2.7. Affinity column based Pull down assay

To find out the possible ID4 protein interactions, the bacterial cell lysate of BL21 (DE3) expressing the protein of interest was allowed to bind to the respective affinity column. For In vitro pull down assay, the protein bound affinity columns were used as bait. The purified recombinant proteins (GST cleaved or His-tagged) were used as prey proteins separately. Alternatively, total cell protein was used as prey protein. The column was washed with at least 15 bed volumes of PBS. The bound proteins were eluted by either glutathione (for GST Baits), imidazole (for His-tagged baits) or simply by 1XSDS buffer. The eluted proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by western-blot analysis.

2.8. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

The nuclear proteins from DU145 and DU145+ID4 cell lines were isolated with the nuclear protein extraction kit (AY2002, Affymetrix). The EMSA was performed using the Affymetrix EMSA Kit (AY1000, Affymetrix) and the 3′ end biotin labelled E-47 EMSA probe set (AY1079P, Affymetrix) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. 2–3ug of nuclear proteins and up to 300nM of recombinant purified proteins was used in the binding reaction. The DNA-protein complex was electrophoretically separated on a 6% non denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The gel was transferred to Nylon membrane and biotin was detected by using streptavidin based chemiluminescent ECL substrate. For competition experiments, unlabeled double stranded probes were added to the reaction mixture.

2.9. Site directed mutagenesis

In-vitro site-directed mutagenesis was performed by using cloned Pfu DNA polymerase (Agilent technologies) on bacterial expression plasmids. The PCR product was first digested overnight with Dpn-I (Promega) and then used to transform JM101 super-competent cells (Agilent). All the mutants were verified by DNA sequencing (Applied Biosciences). Mutations in the HLH domains of ID1 (S74P) and ID4 (S73P) were introduced by PCR using complementary primers incorporating specific site mutations (see below). The deletion of the alanine stretch towards N-terminal of the HLH domain was performed by generating BamH1 sites flanking the alanine stretch (residues 39–48). The resultant plasmid was digested with BamH1, re ligated and transformed.

ID4 site directed mutation from Serine to proline (S73P)

F 5′-ATG AAC GAC TGC TAT CCC CGC CTG CGG AGG-3′

R 5′-CCT CCG CAG GCG GGG ATA GCA GTC GTT CAT-3′

ID1 site directed mutation from Serine to proline (S74P)

F 5′-ATG AAC GGC TGT TAC CCA CGC CTC AAG GAG-3′

R 5′-CTC CTT GAG GCG TGG GTA ACA GCC GTT CAT-3′

ID4 alanine deletion BamH1 site-1

F 5′-AGC CTG GGT GGA TCC GCA GCC GC-3′

R 5′-GCG GCT GCG GAT CCA CCA GGC T-3′

ID4 alanine deletion BamH1 site-2

F 5′-GGC GGC GGC AGC GGG ATC CAA GGC GGC CGA GG-3′

R 5′-CCT CGG CCG CCT TGG ATC CCG CTG CCG CCG CC-3′

2.10. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assay was performed to investigate whether ID4 and ID1 interaction influences the recruitment of E47 transcription factor to E-Box response element in the proximal CDKN1A (p21) in DU145 cells transfected with empty expression vector (DU145+EV) and DU145+ID4 cells. ChIP assay were carried out with Millipore CHIP assay kit (cat# 17-295) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the chromatin fraction was immuno-precipitated with E47 (Santa Cruz) antibody. Parallel controls for each experiment included samples for normal rabbit IgG (negative control) and the input (positive control). After elution and purification, the recovered DNA samples were used as a template for regular PCR (Go-Taq polymerase, Promega) or real time PCR (Syber green, Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The specific primers surrounding the E-box on p21 promoter ware sense (5′-ACC GGC TGG CCT GCT GGA ACT-3′) and antisense (5′-AGC TCA GCG CGG CCC TGA TAT AC-3′) 54.

2.11. E-Box Luciferase Reporter Assay

DU145+EV and DU145+ID4 cells were cultured in 96-well plates to 70–80% confluency and transiently transfected by mixing 5xE-Box-Luciferase plasmid (16, kindly provided by Dr. Mark Israel, Norris Cotton Cancer Center) with pGL4.74 plasmid (hRluc/TK: Renilla luciferase, Promega) DNA in a 10:1 ratio with FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Promega) in a final volume of 100ul of Opti-MEM and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The transfection mix was then added to the cells. After 24 h, the cells were assayed for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities using the Dual- Glo Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) in LUMIstar OPTIMA (MHG Labtech). The results were normalized for the internal Renilla luciferase control.

3. RESULTS

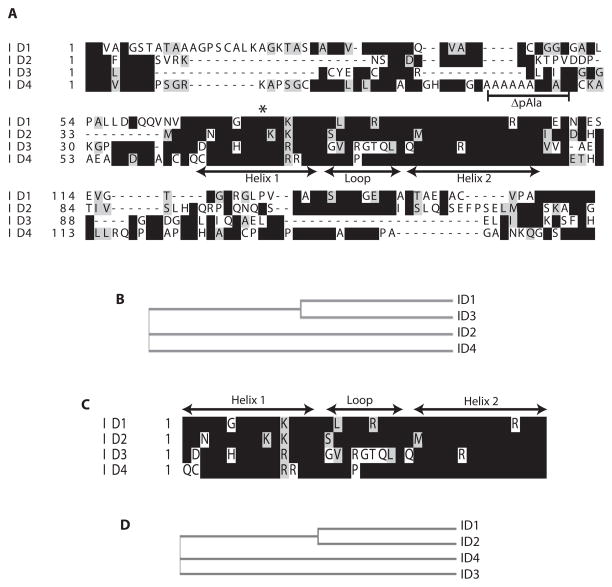

3.1 ID4 sequence is distinct outside of the HLH domain

The sequence of the four ID proteins (ID-1, -2, -3 and -4) with conserved Helix-Loop-Helix domain is shown in Fig. 1A. The full length sequences of ID1 and 3 are more closely related whereas ID-2 and -4 are only distantly related (Fig. 1B). In contrast to the full length sequence, the HLH domain of ID1 and ID2 were closely aligned as compared to ID4 and ID3 (Fig. 1C and D). Nevertheless, ID4 existed as an independent node in full length and HLH only domain based phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1D). These analyses led us to conclude that the sequence of HLH domain and the corresponding flanking sequences could be reflected in their function which remains to be fully understood. The presence of the conserved HLH domain, which is required for hetero- and homodimerization with members of the bHLH proteins, suggests similar interactions within the ID protein family.

Figure 1.

Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis of ID proteins. A: Sequence alignments of full length ID-1, -2, -3 and -4. The conserved residues are highlighted. The Helix1, loop and Helix II of the conserved HLH (Helix-loop-Helix) domain is shown by double sided arrows. The alanine stretch in ID4 that was deleted by site directed mutagenesis is indicated by ΔpAla (deletion of poly Alanine tract). The asterisk indicates the position of conserved serine in helix I which was mutated to proline in ID1 (S74P) and ID4 (S73P). B: The phylogenetic analysis of ID-1, -2, -3 and -4 based on structural homology. C: The alignment of ID1, ID2, ID3 and ID4 HLH domain only. D: Phylogenetic relationship between ID-1, -2, -3 and -4 based on HLH only domain homology. The sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis were performed using MAFFT (Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform).

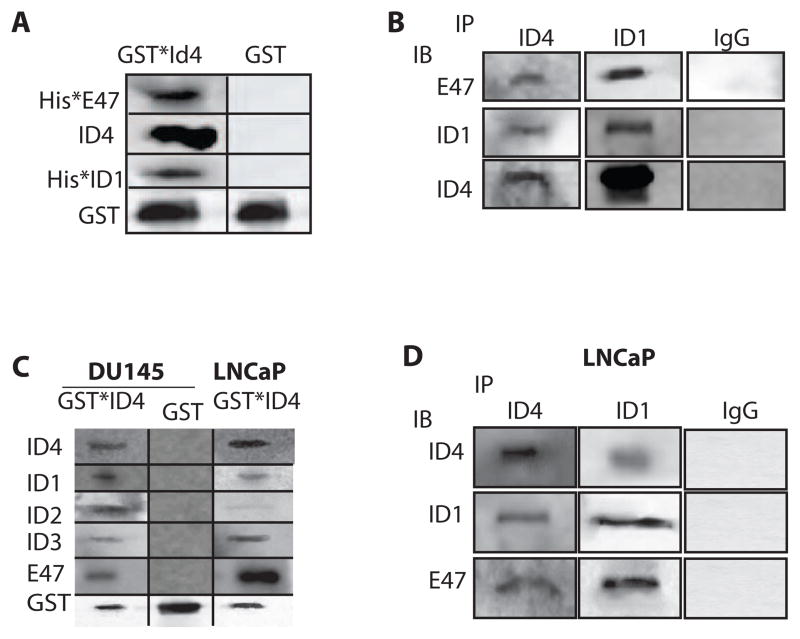

3.2. In vitro interactions between ID4, E47 and ID1

Recombinant GST*ID4 on a GST affinity column demonstrated interaction with recombinant E47 (His*E47) (Fig. 2A) which is consistent with previous studies and confirms ID4-E47 heterodimerization 40. Surprisingly, interaction of ID4 was also observed with recombinant ID1 in a similar GST*ID4 affinity column. The use of equimolar concentration (1uM) of E47 and ID1 in the GST*ID4 interaction study suggested that the affinity of ID4 for both these proteins could be similar. The data suggested a possible ID protein heterodimerization that was investigated and confirmed through multiple approaches as mentioned below.

Figure 2.

Interaction of ID4 with ID-1, -2 and -3. A: On column interaction of Glutathione S-transferase coupled ID4 (GST*ID4) with recombinant Histidine (6x His) tagged E47 (His*E47), His*ID1. The proteins were eluted with 5mM glutathione and the elute was subjected to immuno-blot analysis with protein specific antibodies. The GST tag alone was used as a negative control. B: The antibodies against ID4 or ID1 immobilized on protein A Mag beads were incubated with recombinant ID4, His*ID1 and His*E47. The elute was subjected to immuno-blot (IB) analysis with protein specific antibodies. Non-immune rabbit IgG immobilized on protein A Mag beads and incubated with recombinant proteins as above was used as negative control. C: On column interaction of total cellular proteins isolated from LNCaP and DU145 prostate cancer cell lines with GST*ID4. The bound proteins were eluted with glutathione and subjected to immuno blot analysis with specific antibodies. D: In a format similar to panel B above, the ID4 and ID1 antibodies immobilized on protein A Mag beads were incubated with total cellular proteins from LNCaP cells (immunoprecipitation, IP) followed by elution and IB. The data is representative of at least 4 experiments.

3.3. Recombinant ID1 and E47 immunoprecipitates with ID4

ID4 antibody immobilized on Protein A Mag beads was incubated with recombinant ID4 cleaved from GST with the protease enterokinase. The mixture was then incubated with either recombinant His*E47 (1uM) or His*ID1 (1uM). The resultant immuno- blot (IB) with respective protein specific antibodies indicated immunoprecipitation of ID4 with His*E47 and His*ID1 respectively (Fig. 2B). In a reverse configuration, that is immobilization of ID1 antibody on protein A Mag beads followed by incubation with recombinant His*ID1, ID4 or His*E47, in similar concentrations as noted above, also resulted in the detection of E47 and ID4 in the elute. The specificity of this interaction was confirmed by the lack of any detectable protein when incubated alone or in combination with IgG immobilized on Protein A Mag beads (Fig. 2B). These results further demonstrated that ID4 is capable of heterodimerization with either E47 or ID1 alone.

3.4. Recombinant ID4 interacts with ID1, ID2, ID3 and E47 in cell lysates

Next we sought out to investigate whether ID4-ID1 interaction can be recapitulated in a biological system. We used two different prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP and DU145. LNCaP cell lines express all four ID proteins albeit at different levels 55. In contrast, ID4 is epigenetically silenced in DU145 cell but expresses IDs 1, 2 and 3 26,55. Two different approaches were used to study the interaction specificity of ID4 with other ID proteins. In the first approach, total cell lysate from prostate cancer lines LNCaP and DU145 was passed through GST*ID4 affinity column followed by elution with glutathione. As shown in Fig. 2C, a strong interaction of ID4 was observed in cell lysate from LNCaP and DU145 cells with E47 (positive control), ID1, ID2 and ID3 as detected by immuno-blotting the elute with respective protein specific antibodies. In the second approach, immunoprecipitation (IP) of LNCaP cell lysate was performed with either ID4 or ID1 antibody coupled to Protein A Mag beads (Fig. 2D). The presence of ID1 and E47 in IP with ID4 antibody and ID4 and E47 in IP with ID1 antibody confirmed that ID4-ID1 interaction is also detectable in cells that may be physiologically relevant. These results are significant since the constraints of the in vitro interaction assay using affinity column based bait (GST*ID4) shown in Fig. 2C are minimized in the IP followed by IB on cellular proteins (Fig. 2D).

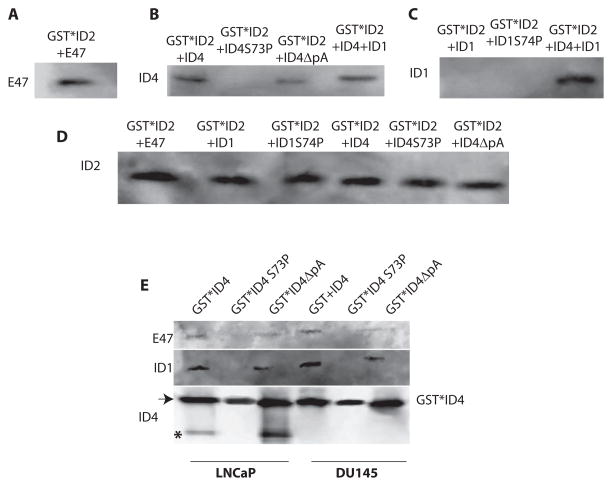

3.5. ID Heterodimerization is specifically mediated by ID4 only

We sought out to determine whether heterodimerization is specifically limited to ID4 or other ID proteins also show a similar property. For these set of experiments we used recombinant GST*ID2 affinity column. A strong interaction of GST*ID2 with recombinant E47 was used as a positive control (Fig. 3A)12. The recombinant ID4 from which GST tag was removed by on column enterokinase digestion was incubated with GST*ID2. The bound proteins were subsequently eluted by either Thrombin (to cleave GST from ID2) or 1xSDS buffer and subjected to immuno-blot analysis with protein specific antibodies. Detection of ID4 in the elute suggested that ID2 also binds to ID4 (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, no binding was observed between GST*ID2 and recombinant His*ID1 in a similar in vitro GST-ID2 pull down assay (Fig. 3C). We then investigated whether ID4 promotes the interaction between IDs 1 and 2. Such a three way interaction could support the role of ID4 as a bridge in forming trimeric structure that could also essentially inactive the ID proteins. As shown in Fig. 3B and C, addition of ID4 in the in vitro GST*ID2+ID1 binding assay, resulted in the detection of ID4 and ID1 respectively. These results are in contrast to the GST*ID2+ID1 interaction which did not result in any detectable interaction (Fig. 3C). Therefore ID4 exhibits a unique property of heterodimerization and heterotrimerization with ID proteins. ID4 can therefore recruit multiple ID proteins to assemble higher order complexes.

Figure 3.

Interaction of wild type ID4 and its various mutants with recombinant ID2 and cellular E47 and ID1. All GST based interactions were on the GST affinity column. The bound proteins were eluted as a complex with thrombin (when GST*ID2 was used as bait, panels A, B, C and D) or glutathione (Panel E) and subjected to immuno-blot using protein specific antibodies indicated on the left side of the blot. A: Interaction between GST*ID2 and E47 was used as a positive control. B, C and D: Interaction of GST*ID2 with ID4, ID4S73P (ID4 HLH mutant) or ID4ΔpA (ID4 in which the alanine tract was deleted, see Fig. 1). The elute was probed with ID4 antibody (panel B), ID1 antibody (Panel C) or ID2 antibody (Panel D, as loading control). E: Interaction of GST*ID4, GST*ID4S73P and GST*ID4ΔpA with total cellular proteins from LNCaP and DU145 cells. The elute was probed with E47, ID1 and ID4 antibodies. The asterisk in the ID4 immuno-blot represents to location of native, cellular ID4 as opposed to GST-ID4 marked by an arrow. Representative of at least 4 experiments is shown.

3.6. HLH Domain is required for ID4 interactions

A number of studies have demonstrated that the HLH domain is required for dimerization between bHLH and HLH proteins such as E47 and IDs 5,11. Therefore a non-functional HLH domain in ID4 should lead to loss of its interaction not only with E47 but also with ID proteins. The HLH domain can be inactivated by mutation of the conserved Serine to Proline residue within Helix 1 of ID1 (S74P) 56 (Fig. 1A, indicated by asterisk). In ID4, this conserved serine is at position 73 (Fig. 1A). Mutation of Serine to proline (S73P) in ID4 resulted in loss of its dimerization with ID2, suggesting that the interaction is dependent on the intact HLH domain of ID4 (Fig. 3B).

Structural studies suggest that none of the N- and C- terminal fragments of any of the ID proteins adopts a helical formation, except the N-terminal 27–64 fragment of ID4 57, a motif that is dictated by the presence of an Alanine-rich motif between residues 39 and 57 (Fig. 1A). Thus the alanine rich N-terminal domain could be a functionally important domain in ID4. In general alanine is a strong alpha-helix former 58 and plays a significant role in protein-protein interactions. Deletion of the alanine residues (39–48, ID4ΔpAla, Fig. 1A) in ID4 did not result in complete abrogation of the binding but the interaction appeared to be significantly weaker as compared to wild type ID4 (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that alanine residues unique to ID4 may be required to structurally stabilize the HLH domain of ID4 for optimal interaction.

In a cross-validation assay, recombinant GST* ID4, GST*ID4 HLH mutant (ID4S73P) and GST*ID4 alanine deletion mutant (ID4ΔpA) was incubated with cell lysates from LNCaP and DU145 cells. As expected, binding between wild type GST*ID4 with E47 and GST*ID4 with ID1 was observed in both cell lysates (Fig. 3E). No binding between E47 and GST*ID4S73P and between ID1 and GST*ID4S73P was observed (Fig. 3E) suggesting that the HLH domain of ID4 is required for heterodimerization with other ID proteins and E47. Similar to in vitro interaction study, as shown in Fig. 3B, decreased binding was observed between GST*ID4 alanine deletion mutant (ID4ΔpA) and E47 or ID1 in cell lysates suggesting that the alanine stretch is required for optimum interaction (Fig. 3E).

Immuno-blotting for ID4 in the above experiment using cell lysates (Fig. 3E) also yielded intriguing results. The presence of GST*ID4 in the elute was expected in all pull down assays (arrow in ID4 IB, Fig. 3E). However, the detection of ID4 alone (smaller band in Fig. 3E, marked by an asterisk) was an unexpected observation. The smaller ID4 band (migrating at native ID4 molecular weight) could be due to cleavage of ID4 from the GST tag, by an unknown protease in cell extracts, even though the column was extensively washed after incubating with protein lysates and elution was performed with reduced glutathione. Alternatively, the ID4 could be a native cellular protein since this band was observed only in ID4 expressing LNCaP cells and not in ID4 non-expressing DU145 cells. Moreover, this band was not eluted from the HLH mutant GST*ID4S73P column. These results led us to believe that the smaller ID4 immuno-reactive band could be due to homodimerization of GST*ID4 with cellular ID4. Thus ID4 is capable of homodimerization that requires an intact HLH domain.

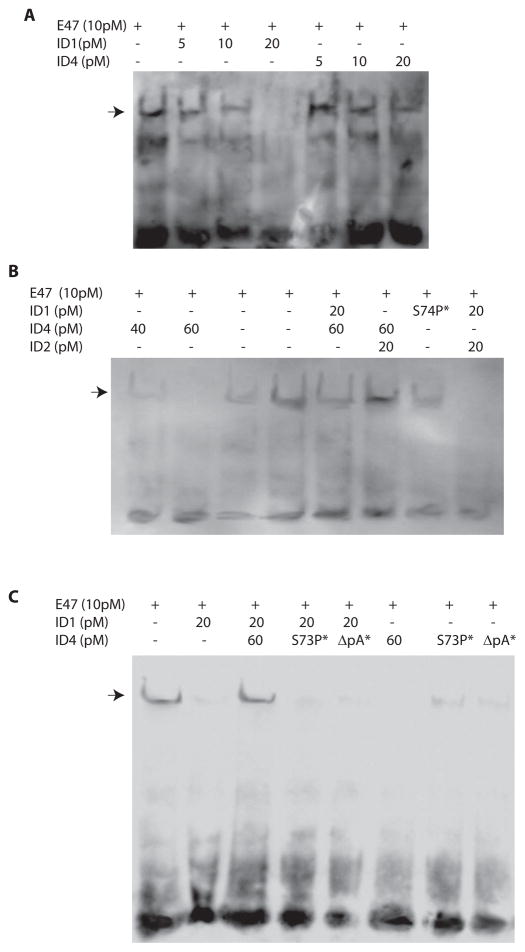

3.7. E47 DNA binding is inhibited by ID4 to a lesser extent than ID1

EMSA was performed to further investigate the effect of ID4-ID1 heterodimerization on DNA binding of bHLH protein E47. Unlike E12, the other spliced variant of the E2A gene which can only heterodimerize 59, E47 on the other hand preferentially homodimerizes 60. Thus in EMSA, E47 alone can result in a gel shift with an E-Box double stranded oligonucleotide (Fig. 4A). The interaction between recombinant bHLH protein E47 with consensus double stranded E-Box oligonucleotide was progressively decreased in the presence of increasing concentrations of ID1 (5–20pM) (Fig.4A, B and C). Whereas 20pM of ID1 completely inhibited the binding of E47 to E-Box oligo, ID4 at a similar concentration (20pM) only marginally decreased the interaction between E47 and E-Box (Fig. 4A). ID4 at 60pM concentration (3 times higher than ID1) completely abrogated the binding of E47 to E-Box (Fig. 4B, C and D), suggesting that ID4 could have lower affinity for E47 as compared to ID1.

Figure 4.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) demonstrating interaction between double stranded consensus E-Box oligonucleotide and recombinant E47 in the presence or absence of recombinant ID1 and/or ID4. A, B and C: The double stranded E-Box oligonucleotide was incubated with 10pM of recombinant E47 either alone or in the presence of ID1 (A, B and C), ID4 (A, B and C), ID2 (B), HLH mutant (S74P) of ID1 (B), HLH mutant of ID4 (S73P, C) or with ID4 in which alanine tract was deleted ΔpA, C). The GST tag from ID4 (and its mutants) and ID2 was removed with respective on column protease digestion. The E47 and ID1 retained the histidine tag. All concentrations are in Pico moles (pM). The ID1 S75P* and ID4 (S73P* and ΔpA*) mutants were used at 20pM and 60pM respectively. The arrows indicate the gel shift due to the binding between E-Box oligonucleotide and E47. The free probe is at the bottom of the gel. The data is representative of at least 3 different experiments using recombinant proteins from different batches.

3.8. ID4 restores E47 DNA binding even in the presence of ID1 and ID2

No E47-E-Box binding was observed when recombinant ID1 and ID2, either alone or in combination were added to the binding reaction (Fig. 4A and B). Interestingly, inclusion of ID4 at 60pM concentration (which abrogates E47 DNA binding, Fig. 4A and B) in the E47+ID1 or E47+ID2 binding assay restored E47 DNA binding suggesting that ID4 indeed heterodimerizes with ID1 and ID2 as shown in Fig. 1 (Fig. 2B and C). These results further demonstrated that ID4-ID1/2 interaction results in the neutralization of ID1/2 resulting in increased binding of bHLH proteins to the E-Box response element even at ID4 concentration which normally blocks E47 DNA binding. A similar E47 DNA binding was not observed when ID2 (at 20pM) concentration which blocks E47 DNA binding, last lane, Fig. 2B) was added to the E47-ID1 binding reaction suggesting that only ID4 heterodimerizes with ID1 as shown in Figs 2 and 3. These results were further confirmed by including ID4 mutants in the binding reaction. As expected, the E47 DNA binding was observed with ID4S73P HLH mutant at 60pM concentration (Fig. 4C). These results established that the ID4S73P HLH mutant abrogates the HLH domain of ID4 that is required for efficient interaction with E47. However, the ID4ΔpA mutant also restored E47 DNA binding but to a lesser extent suggesting the poly alanine stretch in ID4 is necessary for optimum ID4 dominant negative activity (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, the ID4S73P HLH mutant could not restore the E47 DNA binding in presence of ID1 suggesting that intact ID4 HLH domain is required for efficient heterodimerization with ID1 (Fig. 4C). These results also confirmed the interaction studies shown in Fig. 3 demonstrating that ID4 HLH mutant results in loss of interaction with IDs1/2. Similar results were obtained with ID4ΔpA mutant that is lack of E47 DNA binding in the presence of ID1 (Fig. 4C). Collectively, the results suggested that ID4-ID1 heterodimerization promotes E47 DNA binding that is dependent on intact HLH and poly alanine stretch of ID4 suggesting the functional significance of these domains.

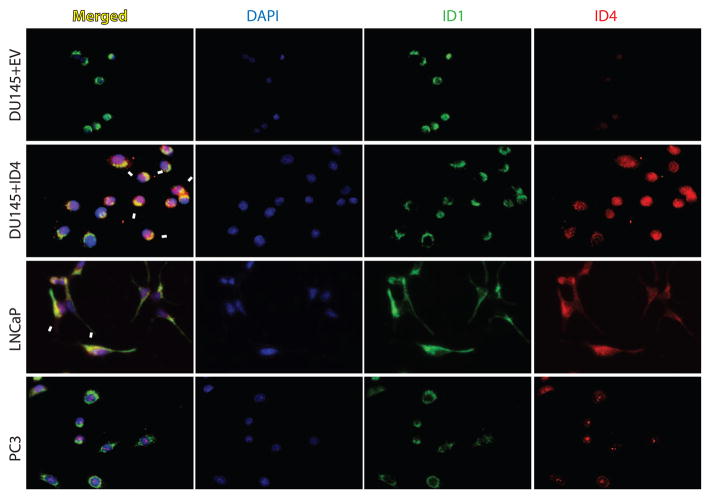

3.9. ID4 and ID1 co-localizes in prostate cancer cells

ID1 and ID4 immunolocalization was investigated in prostate cancer cells by fluorescence immunocytochemistry to further demonstrate the interaction at the cellular level. All three prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP, DU145 and PC3 express ID1 (Fig. 5). High, intermediate and no ID4 expression is observed in LNCaP, PC3 and DU145 cells respectively (Fig. 5). ID4 and ID1 was co-localized in LNCaP cells which expresses both the proteins as seen by yellow fluorescence due to overlapping ID1 (green) and ID4 (red) signals. Interestingly, the colocalization appeared to more cytoplasmic than nuclear. In PC3 cells, no detectable ID4-ID1 colocalization was observed possibly due to low expression of ID4 and/or predominantly nuclear localization as compared to ID1 which appeared cytoplasmic. Thus given the limits of detection, it will be difficult to visualize interactions

Figure 5.

ColocalizationColocalization of ID1 and ID4 in prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP, DU145 and PC3. ID1 (green) and ID4 (red) were detected by fluorescence based immunocytochemistry. The merged images were used to detect colocalization (yellow, Merged) of ID1 and ID4. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. Immuno-localization studies were also performed in DU145 cells in which ID4 was over expressed (DU145+ID4) and compared to cells transfected with vector alone (DU145+EV). The arrows indicate colocalization which was observed in LNCaP and DU145+ID4 cells. No colocalization was observed in DU145+EV cells due to the lack of expression of ID4. A representative image of three different experiments is shown. All images are at 200X magnification.

We next investigated the colocalization of ID1 and ID4 in DU145 cells over-expressing ID4 (DU145+ID4). As shown in Fig. 5, high ID4 expression was observed in DU145+ID4 cells as compared to cells stably transfected with empty vector (DU145+EV). A strong colocalization signal (yellow) was observed between ID4 and ID1 in DU145+ID4 cells as compared to DU145+EV cells. As seen with LNCaP cells, the colocalization appeared to be cytoplasmic/peri nuclear than nuclear.

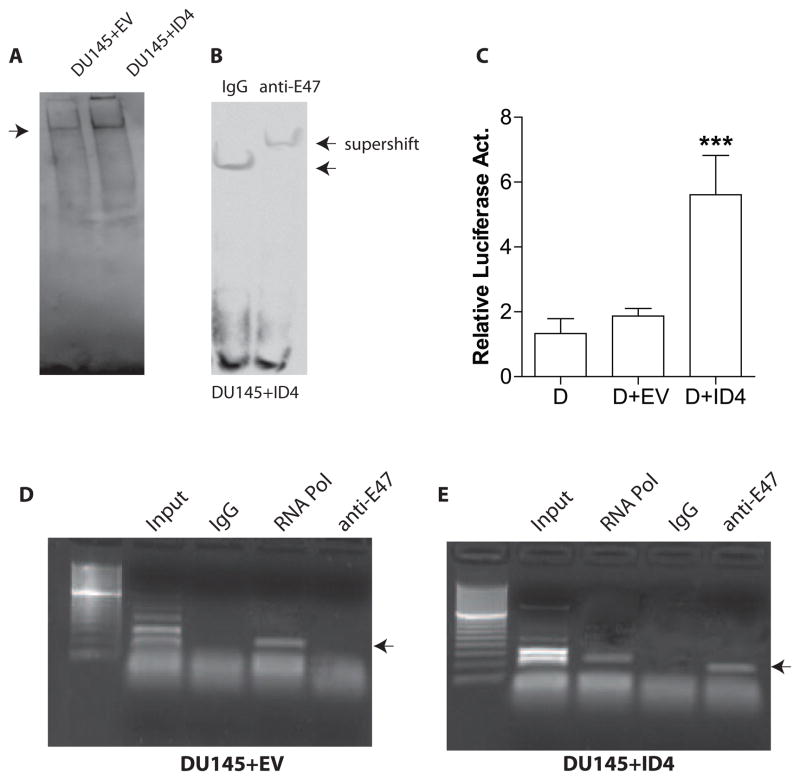

3.10. ID4 Promotes E47 DNA binding and Luciferase reporter activity

Finally, we investigated the biological significance of increased ID4 expression on E-Box activity. The experiments were performed using DU145+ID4 cells and their corresponding control (DU145+EV). Increased E-Box protein binding was observed in DU145+ID4 cells as compared DU145+EV cells in an EMSA (Fig. 6A). Super shift assay using E47 antibody in the binding reaction indicated that E-Box gel shift in DU145+ID4 cells was due to the binding of E47 (Fig. 6B). These results prompted us to investigate whether ectopic expression of ID4 in DU145 cells could also result in in an increased E-Box transcriptional activity in a luciferase reporter assay. The relative E-Box luciferase activity (normalized to Renilla Luciferase, transfected in 10:1 ratio) in DU145+ID4 cells was significantly higher as compared to DU145+EV cells (p<0.001) suggesting that increased ID4 expression promotes E-Box luciferase activity (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

E-Box binding and transcriptional activity in DU145 cells over-expressing ID4. A: Four microgram (4ug) of nuclear extracts from DU145+EV (empty vector) and DU145+ID4 cells were used in the EMSA to demonstrate relative binding to consensus E-Box. Though not quantitative, a stronger signal of the shifted band (indicated by arrow) in DU145+ID4 suggests higher E-Box DNA binding relative to DU145+EV cells. B: The supershift using E47 specific antibody was to ascertain that the gel shift using DU145+ID4 nuclear extracts was due to the binding of E47 to E-Box oligonucleotide. Non-immune IgG was used as a negative that did not result in a supershift. C: Relative E-Box luciferase reporter activity in DU145 (D), DU145+EV (D+EV) and DU145+ID4 (D+ID4) cells. The results were first normalized to Renilla luciferase and then to DU145 cells (set to 1). The data is expressed as mean+SEM of three experiments in triplicate. The significance of differences between means were analyzed by student’s t-test (***: P<0.001). D and E: Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of E47 on CDKN1A proximal promoter in DU145+EV (D) and DU145+ID4 (E) cells. A clear PCR band (anti-E47 lane) was observed on the reverse cross-linked product in DU145+ID4 cells using primers around the E-Box site known to bind E47. A similar product was absent/un-detectable in DU145+EV cells. The lanes with Input, IgG alone (negative control) and RNA Pol II is shown. The RNA PolII was observed in DU145+ID4 cells suggesting active transcription of CDKN1A. Representative data of three different experiments is shown.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A, p21) transcription is up-regulated by the binding of E47 to the E-Box response element within its proximal promoter 54. Increased ID1 expression abrogates the binding between E47 and CDKN1A promoter E-Box response element which results in decreased expression of CDKN1A 54. We have previously shown increased p21 expression in DU145+ID4 cells as compared to DU145+EV cells 26,49. We reasoned that ectopic expression of ID4 in DU145 cells, could heterodimerize with ID1 and promote the binding of E47 resulting in increased expression of CDKN1A. In order to test this hypothesis we performed Chromatin-Immunoprecipitation at the E-Box site on the CDKN1A promoter. The ChIP analysis using anti-E47 antibody followed by PCR around the E-Box response element indicated lack of a PCR product in DU145+EV cells which suggested that low to undetectable E47 binding to E-Box response element in CDKN1A promoter in DU145+EV cells (Fig. 6D). In contrast, a strong PCR product was observed in a ChIP reaction using anti-E47 antibody in DU145+ID4 cells suggesting increased binding of E47 to the E-Box response element in CDKN1A promoter (Fig. 6E), that is consistent with the its expression. These results further confirmed that increased ID4 expression promotes the interaction of E47 with E-Box response element, an unexpected result given that ID4, an HLH protein is generally considered as dominant negative inhibitor of bHLH proteins such as E47.

4. DISCUSSION

Majority of interactions between ID proteins and bHLH proteins, particularly those involving E-proteins (E2A spliced variants, E2-2 and HEB) and myogenic proteins (i.e. MyoD) are largely similar that depends primarily on temporal expression profile of a specific ID protein subtype 11,12. However, ID subtype specific interactions with bHLH and non-bHLH proteins are known that are also reflected as unique phenotypes in gene specific knockout mouse models 61. Interestingly, the expression but not necessarily the function of ID proteins, particularly ID-1, -2 and -3 converge in cancer cells. Increased ID-1, -2 and -3 expression in cancer cells is generally considered as pro-oncogenic and associated with poor prognosis 61,62. In contrast, the expression of ID4 is down-regulated in many cancers 26–35. In cancers such as glioblastoma, where ID1 is also highly expressed 63 and promotes MMP2 expression, concomitant ID4 expression is associated with favorable prognosis and suppression in MMP2 expression 64 suggesting that ID4 may attenuate ID1 activity. The function of ID4 appears to be particularly relevant in prostate cancer. ID4 expression is generally down-regulated in prostate cancer 26,51,65 and regulates androgen sensitivity 50 whereas increased ID1 expression results in androgen insensitivity 66, a hall mark of advanced disease with poor prognosis. Genetic ablation of ID4 in prostate cancer cells results in androgen insensitivity and promotes tumor growth in castrated mouse xenograft models 50. Thus ID4 expression and function is highly relevant in cancer initiation and progression. Multiple mechanisms including protein specific interactions targeting specific transcriptional/signaling pathways could be envisioned that could lead to the pro-tumorigenic (IDs1, 2 and 3) and anti-tumorigenic (ID4) functions of ID proteins. In this study we demonstrate the heterodimerization within ID protein family as a new mechanism which could eventually determine their role as regulators of bHLH/non-bHLH proteins and determine the functional outcome as pro- or anti-tumorigenic.

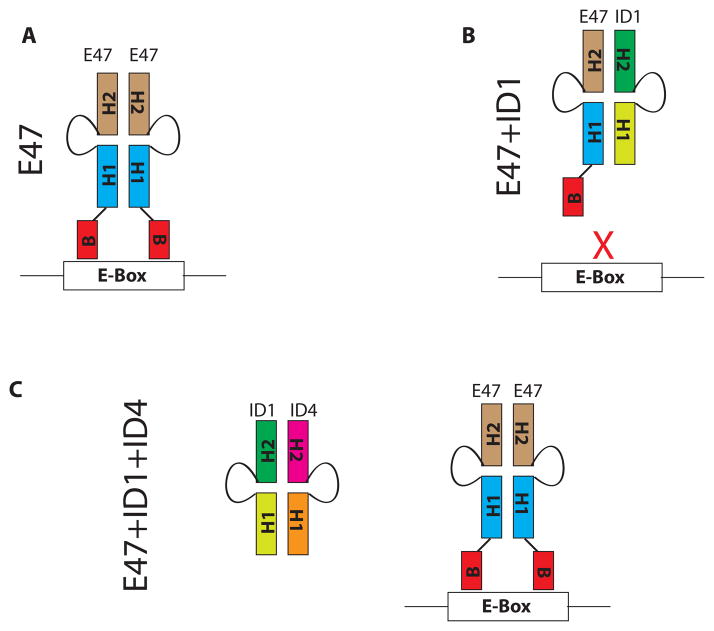

We show that heterodimerization within the ID protein family is limited to ID4 as demonstrated by multiple experimental approaches including in vitro recombinant and native protein interactions, co-immunoprecipitation and cellular colocalization studies with ID1, ID2 and ID3. Earlier Loveys et al also demonstrated an interaction of ID3 with ID4 in a yeast two hybrid assay; however this interaction was less efficient in a co-immunoprecipitation assay. The authors demonstrated no interaction between ID3 and ID1 was observed in either yeast two hybrid assay or co-immunoprecipitation assay 67. The major functional consequence of this interaction appears to be twofold: 1) restoration of DNA binding by bHLH protein E47 in presence of ID1/2, an unexpected outcome which is counterintuitive to the established role of ID4 as dominant negative regulator bHLH transcription factors as a result of 2) neutralization of pro-oncogenic proteins ID-1, -2 and -3. Thus ID4 essentially acts as an inhibitor of inhibitor of differentiation proteins ID-1, -2 and -3 (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed schematic representing the mechanism by which ID4 restores bHLH-DNA interaction. A: bHLH proteins such as E47 bind DNA as homodimers or heterodimers with tissue bHLH proteins. The dimerization involves the conserved helix-loop-helix domain (represented by H1 and H2 with intertwining loop) whereas the basic domain (B) binds the E-Box. B: ID1 heterodimerizes with bHLH proteins through the conserved HLH domain. The lack of basic domain in ID1 renders the heterodimer incapable of binding the DNA. Thus ID1 essentially acts as a dominant negative inhibitor of bHLH transcription factors. C: ID4, a distant member of the ID protein family could acts as an inhibitor of inhibitor of differentiation proteins such as ID1. ID4 hetero-dimerizes with ID1 which allows bHLH dimerization, subsequent DNA binding and transcriptional regulation of E-Box dependent genes.

The results from this study also points to a larger question: What could be the biological purpose of an inhibitor of a dominant negative protein in normal cell physiology? The evidence of such an interaction between similar dominant negative regulators is not well established partly because the ID family is unique that acts through sequestration of transcription factors of the bHLH (e.g. E2A and TWIST68) and non-bHLH family (Ets17, Rb16). However, extensive literature review revealed that the transcriptional repressors E2F7 and E2F8 also co-exist in a DNA binding complex and repress certain E2F target genes 69. An interaction, specifically between ID4 and ID-1,-2 and -3 could serve as a regulatory step not only in cancer cells but also in many normal cells. In cancer cells such a regulatory step will be essential in determining whether the cell gains (increased ratio between ID1 and ID4) metastatic potential and/or resistance to chemo-therapeutic drugs. In normal cells, the decrease in the ratio between ID1 and ID4 could decide the timing of differentiation. In fact interactions within the ID protein family should be advantageous to the cell as it can integrate multiple pathways regulated by bHLH proteins. Even though we only studied the interaction of ID4 with well-known bHLH protein E47, but its interactions with other bHLH proteins such as TWIST168 could also be a regulatory step in limiting the aggressiveness of glioblastoma. Alternatively, interactions between ID proteins could also regulate subsequent protein degradation. For example, Interaction of ID1 with E47 leads to marked increase in the half-life of ID170. Unlike Id1, Id2 and Id3 which are degraded via the 26 proteosome pathway, the ubiquitinated Id4 is largely rescued from degradation by a deubiquitination mechanism 71. One can envision a similar mechanism in which preferential ID protein interactions could regulate proteosomal degradation of not only ID proteins but other interacting proteins also.

The HLH synthetic peptides alone have a strong propensity to self-associate in solution 72. The HLH only peptide of ID1 exists as a tetramer due to dimerization of homodimers in solution that has significantly higher cooperativity and affinity for heterotetramerization with the MyoD bHLH peptide 72. In contrast, the full length ID1 and ID2 homodimerize poorly 12. Homology modeling suggested that the inability of ID1 to form homodimers is due to charge repulsions between Helix 1 and Helix 2 whereas possible ID3 homodimerization is largely due to favorable contacts within Helix 1 and Helix 2 73,74. Our results suggest that unlike ID1 and ID2, full length ID4 can homodimerize which requires intact HLH domain. Thus homodimerization between ID proteins is largely dependent on the N- and C- terminal domains including an intact HLH domain for biologically relevant interaction and function. Evidence presented in this study suggests that a structural domain present in ID4 outside of the HLH conserved domain could contribute to the unique property of ID4 mediated hero-dimerizations.

The strong alpha helix forming poly-alanine (p-Ala) tract specific (reviewed in 75) to the N-terminal end of HLH domain in ID4 appears to play a role in ID4 dependent interactions. The p-Ala tract in ID4 is consistent with similar tracts which are preferentially found in many transcription factors and lies outside, usually towards the N-terminal of the functional domains (such as N-terminal to HLH domain in ID4). The p-Ala tract functions as a flexible spacer element located between functional domain of a protein and therefore essential to protein conformation, protein–protein interactions and/or DNA binding 75. The length of the p-Ala stretch in ID4 (n=10) is also within threshold for normal function whereas an increase in the length beyond this threshold results in human diseases (≤10) 76. Thus weakened but not complete loss in the interaction of ID4 Δp-Ala mutants with full length IDs 1, 2 and the bHLH E47 strengthens the functional role of p-Ala tract in ID4. Apparently, the ID4 Δp-Ala had no significant effect on ID4 homodimerization suggesting that additional structural domains could be involved in ID4 homodimerization which is not present in IDs1 and 2. In contrast, the ID4 HLH mutant (S73P) completely abrogated ID4 homodimerization demonstrating the central role of the HLH core functional domain. Surprisingly, the ID4 ΔpA mutant, similar to S73P HLH mutant could not restore the E47 binding in presence of ID1 suggesting that under DNA binding conditions, the alanine tract plays a critical role in blocking ID1 from interacting with E47. These results suggest that the p-Ala stretch is required for heterodimerization of ID4 but dispensable for homodimerization.

Functionally, ID4 appears to be distinct from ID-1, -2 and -3, in terms of structure, function and expression. ID4 inhibits proliferation 26,49, promotes differentiation in certain cell types 77–80 and promotes apoptosis 81. In contrast, ID-1, -2 and -3 promote proliferation, inhibit differentiation and are generally considered as anti-apoptotic 82. The experimental evidence also suggests that ID-1, -2 and -3 acts as negative regulators of CDKNIs p16 and p21 primarily by blocking the E-Box dependent transcriptional activity of bHLH proteins such as E47/E12 16,45,54,83. ID4 on the other hand promotes the expression of CDKNIs which could be one of the mechanisms by which it inhibits proliferation 26. Mechanistically, ID4 could homodimerize which could allow efficient bHLH E47/E12 homo-, hetero- dimerization. Alternatively, ID4 could inactivate ID-1, -2 and -3 through heterodimerization and coupled with the lower affinity of ID4 for E12/E47, could favor transcriptionally active bHLH heterodimerization and subsequent activation of E-Box dependent promoters such as p21.

A strong association between increased ID-1, -2 and -3 expression with cancer suggests that these proteins are promising candidates for cancer therapy. Thus molecules targeting/blocking the function of ID-1, -2 and -3 will be promising anti-cancer candidates. Progress have been made in targeting IDs through either regulating their expression by antisense oligonucleotides 84 or blocking function at the protein level by generating libraries of small peptides 85, aptamers 86 or small molecules such as AGX51 87 against IDs. Based on our studies, ID4 represents a new model structure for developing such anti-ID molecules. We expect that ID4 dependent regulation of ID-1, -2 and -3 will not be limited to bHLH proteins only. Apart from bHLH proteins, ID proteins interact with a large number of non-bHLH proteins including Rb, CASK, ELK1/4, GATA4, ETS1, CAV1, PAX2/5/8, CDK2, ATF3, UBC etc. These diverse interactions can significantly expand the regulatory network of ID4. The structural domains/features that mediate the heterodimerization of ID4 with ID-1, -2 and -3 could provide strong leads for the rational development of peptides/ aptamers/ small molecules for effectively blocking the function of ID proteins.

Some of the experimental approaches in this study, for example the use immobilized proteins on the columns demonstrating ID protein interactions could be an over-interpretation of the results. However, subsequent experiments such as coimmunoprecipitation and colocalization studies strongly support the interaction studies reported herein. Although we used only prostate cancer cell lines to demonstrate colocalization of ID4 with ID-1, -2 and -3, we feel that that similar observations in additional cell lines should further used to establish the interactions of ID4 with ID-1, -2 and -3. Moreover, a direct interaction between recombinant ID3 and ID4 needs to be examined. Our efforts to show such an interaction were largely unsuccessful because we were not able to produce sufficient quantities of purified recombinant protein for in-vitro assays. Additionally, the presence of E47 in cell lines could promote heterotrimeric complexes that could lead to the detection of interactions between ID1 and ID4. However direct interactions using in-vitro recombinant proteins suggests that the possibility of such a heterotrimeric complex involving E47 is low.

In conclusion, our results have established a new mechanism of action of ID4 that could explain its anti-cancer activity. This mechanism involves heterodimerization with ID-1, -2 and -3 that eventually results in counteracting their biological activities (Fig. 7). The epigenetic silencing of ID4 in majority of cancers, possibly involving EZH2 dependent H3K27me3 as shown recently in prostate cancer 88 suggests that EZH2 inhibitors could be used to up-regulate ID4. Alternatively, targeted delivery of ID4 sequence/structure based biologicals/small molecules presents a new approach for anti-cancer drug design. The strength of our proposed mechanism of action of ID4 is based on the use of functional, full length proteins and site specific mutations that abrogate their function in relevant cellular systems. However, detailed structural studies will be required to unravel the underlying mechanisms involved in ID mediated dimerizations.

Highlights.

ID4 acts as inhibitor of Inhibitor of Differentiation (IDs 1, 2 and 3) proteins

ID4 hetero-dimerizes and neutralizes the oncogenic activity of IDs 1, 2 and 3

The alpha helix forming alanine stretch in ID4 is required for protein interactions

The proposed mechanism supports the role of ID4 as tumor suppressor

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by NIH/NCI CA128914 (JC) and in part by NIH/NCRR/RCMI G12MD007590 (CCRTD).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Massari ME, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(2):429–440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ledent V, Vervoort M. The basic helix-loop-helix protein family: comparative genomics and phylogenetic analysis. Genome Res. 2001;11(5):754–770. doi: 10.1101/gr.177001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atchley WR, Fitch WM. A natural classification of the basic helix-loop-helix class of transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(10):5172–5176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murre C, Bain G, van Dijk MA, Engel I, Furnari BA, Massari ME, Matthews JR, Quong MW, Rivera RR, Stuiver MH. Structure and function of helix-loop-helix proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murre C, McCaw PS, Vaessin H, Caudy M, Jan LY, Jan YN, Cabrera CV, Buskin JN, Hauschka SD, Lassar AB, Weintraub H, Baltimore D. Interactions between heterologous helix-loop-helix proteins generate complexes that bind specifically to a common DNA sequence. Cell. 1989;58(3):537–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bain G, Gruenwald S, Murre C. E2A and E2-2 are subunits of B-cell-specific E2-box DNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(6):3522–3529. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu JS, Olson EN, Kingston RE. HEB, a helix-loop-helix protein related to E2A and ITF2 that can modulate the DNA-binding ability of myogenic regulatory factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(3):1031–1042. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murre C, McCaw PS, Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989;56(5):777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lassar AB, Davis RL, Wright WE, Kadesch T, Murre C, Voronova A, Baltimore D, Weintraub H. Functional activity of myogenic HLH proteins requires hetero-oligomerization with E12/E47-like proteins in vivo. Cell. 1991;66(2):305–315. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90620-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longo A, Guanga GP, Rose RB. Crystal structure of E47-NeuroD1/beta2 bHLH domain-DNA complex: heterodimer selectivity and DNA recognition. Biochemistry. 2008;47(1):218–229. doi: 10.1021/bi701527r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benezra R, Davis RL, Lockshon D, Turner DL, Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun XH, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Baltimore D. Id proteins Id1 and Id2 selectively inhibit DNA binding by one class of helix-loop-helix proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11(11):5603–5611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barone MV, Pepperkok R, Peverali FA, Philipson L. Id proteins control growth induction in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(11):4985–4988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara E, Yamaguchi T, Nojima H, Ide T, Campisi J, Okayama H, Oda K. Id-related genes encoding helix-loop-helix proteins are required for G1 progression and are repressed in senescent human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(3):2139–2145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moldes M, Lasnier F, Feve B, Pairault J, Djian P. Id3 prevents differentiation of preadipose cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(4):1796–1804. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lasorella A, Iavarone A, Israel MA. Id2 specifically alters regulation of the cell cycle by tumor suppressor proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(6):2570–2578. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yates PR, Atherton GT, Deed RW, Norton JD, Sharrocks AD. Id helix-loop-helix proteins inhibit nucleoprotein complex formation by the TCF ETS-domain transcription factors. Embo J. 1999;18(4):968–976. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lasorella A, Stegmuller J, Guardavaccaro D, Liu G, Carro MS, Rothschild G, de la Torre-Ubieta L, Pagano M, Bonni A, Iavarone A. Degradation of Id2 by the anaphase-promoting complex couples cell cycle exit and axonal growth. Nature. 2006;442(7101):471–474. doi: 10.1038/nature04895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Ling MT, Wang Q, Lau CK, Leung SC, Lee TK, Cheung AL, Wong YC, Wang X. Identification of a novel inhibitor of differentiation-1 (ID-1) binding partner, caveolin-1, and its role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and resistance to apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(46):33284–33294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoppmann SF, Schindl M, Bayer G, Aumayr K, Dienes J, Horvat R, Rudas M, Gnant M, Jakesz R, Birner P. Overexpression of Id-1 is associated with poor clinical outcome in node negative breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(6):677–682. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang HY, Liu HL, Liu GY, Zhu H, Meng QW, Qu LD, Liu LX, Jiang HC. Expression and Prognostic Values of Id-1 and Id-3 in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. J Surg Res. 2009:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schindl M, Oberhuber G, Obermair A, Schoppmann SF, Karner B, Birner P. Overexpression of Id-1 protein is a marker for unfavorable prognosis in early-stage cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61(15):5703–5706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forootan SS, Wong YC, Dodson A, Wang X, Lin K, Smith PH, Foster CS, Ke Y. Increased Id-1 expression is significantly associated with poor survival of patients with prostate cancer. Hum Pathol. 2007;38(9):1321–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schindl M, Schoppmann SF, Strobel T, Heinzl H, Leisser C, Horvat R, Birner P. Level of Id-1 protein expression correlates with poor differentiation, enhanced malignant potential, and more aggressive clinical behavior of epithelial ovarian tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(2):779–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benezra R, Rafii S, Lyden D. The Id proteins and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20(58):8334–8341. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carey JP, Asirvatham AJ, Galm O, Ghogomu TA, Chaudhary J. Inhibitor of differentiation 4 (Id4) is a potential tumor suppressor in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slovak ML, Bedell V, Hsu YH, Estrine DB, Nowak NJ, Delioukina ML, Weiss LM, Smith DD, Forman SJ. Molecular karyotypes of Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells at disease onset reveal distinct copy number alterations in chemosensitive versus refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(10):3443–3454. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu L, Liu C, Vandeusen J, Becknell B, Dai Z, Wu YZ, Raval A, Liu TH, Ding W, Mao C, Liu S, Smith LT, Lee S, Rassenti L, Marcucci G, Byrd J, Caligiuri MA, Plass C. Global assessment of promoter methylation in a mouse model of cancer identifies ID4 as a putative tumor-suppressor gene in human leukemia. Nat Genet. 2005;37(3):265–274. doi: 10.1038/ng1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castro M, Grau L, Puerta P, Gimenez L, Venditti J, Quadrelli S, Sanchez-Carbayo M. Multiplexed methylation profiles of tumor suppressor genes and clinical outcome in lung cancer. Journal of translational medicine. 2010;8:86. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noetzel E, Veeck J, Niederacher D, Galm O, Horn F, Hartmann A, Knuchel R, Dahl E. Promoter methylation-associated loss of ID4 expression is a marker of tumour recurrence in human breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uhm KO, Lee ES, Lee YM, Kim HS, Park YN, Park SH. Aberrant promoter CpG islands methylation of tumor suppressor genes in cholangiocarcinoma. Oncology research. 2008;17(4):151–157. doi: 10.3727/096504008785114110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Candia P, Akram M, Benezra R, Brogi E. Id4 messenger RNA and estrogen receptor expression: inverse correlation in human normal breast epithelium and carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(8):1032–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Umetani N, Takeuchi H, Fujimoto A, Shinozaki M, Bilchik AJ, Hoon DS. Epigenetic inactivation of ID4 in colorectal carcinomas correlates with poor differentiation and unfavorable prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(22):7475–7483. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen SS, Claus R, Lucas DM, Yu L, Qian J, Ruppert AS, West DA, Williams KE, Johnson AJ, Sablitzky F, Plass C, Byrd JC. Silencing of the inhibitor of DNA binding protein 4 (ID4) contributes to the pathogenesis of mouse and human CLL. Blood. 2011;117(3):862–871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-284638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan AS, Tsui WY, Chen X, Chu KM, Chan TL, Li R, So S, Yuen ST, Leung SY. Downregulation of ID4 by promoter hypermethylation in gastric adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22(44):6946–6953. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S, Kon M, DeLisi C. Pathway-based classification of cancer subtypes. Biology direct. 2012;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren Y, Cheung HW, von Maltzhan G, Agrawal A, Cowley GS, Weir BA, Boehm JS, Tamayo P, Karst AM, Liu JF, Hirsch MS, Mesirov JP, Drapkin R, Root DE, Lo J, Fogal V, Ruoslahti E, Hahn WC, Bhatia SN. Targeted tumor-penetrating siRNA nanocomplexes for credentialing the ovarian cancer oncogene ID4. Science translational medicine. 2012;4(147):147ra112. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venneti S, Le P, Martinez D, Xie SX, Sullivan LM, Rorke-Adams LB, Pawel B, Judkins AR. Malignant rhabdoid tumors express stem cell factors, which relate to the expression of EZH2 and Id proteins. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(10):1463–1472. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318224d2cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng W, Rushing EJ, Hartmann DP, Azumi N. Increased inhibitor of differentiation 4 (id4) expression in glioblastoma: a tissue microarray study. Journal of Cancer. 2010;1:1–5. doi: 10.7150/jca.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riechmann V, van Cruchten I, Sablitzky F. The expression pattern of Id4, a novel dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein, is distinct from Id1, Id2 and Id3. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(5):749–755. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.5.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jen Y, Manova K, Benezra R. Each member of the Id gene family exhibits a unique expression pattern in mouse gastrulation and neurogenesis. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1997;208(1):92–106. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199701)208:1<92::AID-AJA9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riechmann V, Sablitzky F. Mutually exclusive expression of two dominant-negative helix-loop-helix (dnHLH) genes, Id4 and Id3, in the developing brain of the mouse suggests distinct regulatory roles of these dnHLH proteins during cellular proliferation and differentiation of the nervous system. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6(7):837–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jen Y, Manova K, Benezra R. Expression patterns of Id1, Id2, and Id3 are highly related but distinct from that of Id4 during mouse embryogenesis. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1996;207(3):235–252. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199611)207:3<235::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carey JP, Knowell AE, Chinaranagari S, Chaudhary J. Id4 Promotes Senescence and Sensitivity to Doxorubicin-induced Apoptosis in DU145 Prostate Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(10):4271–4278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alani RM, Young AZ, Shifflett CB. Id1 regulation of cellular senescence through transcriptional repression of p16/Ink4a. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(14):7812–7816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141235398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samanta J, Kessler JA. Interactions between ID and OLIG proteins mediate the inhibitory effects of BMP4 on oligodendroglial differentiation. Development. 2004;131(17):4131–4142. doi: 10.1242/dev.01273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng W, Wang H, Xue L, Zhang Z, Tong T. Regulation of cellular senescence and p16(INK4a) expression by Id1 and E47 proteins in human diploid fibroblast. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(30):31524–31532. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qi J, Su Y, Sun R, Zhang F, Luo X, Yang Z, Luo X. CASK inhibits ECV304 cell growth and interacts with Id1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328(2):517–521. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knowell A, Patel D, Morton D, Sharma P, Glymph S, Chaudhary J. Id4 dependent acetylation restores mutant-p53 transcriptional activity. Molecular Cancer. 2013;12(1):161. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel D, Knowell AE, Korang-Yeboah M, Sharma P, Joshi J, Glymph S, Chinaranagari S, Nagappan P, Palaniappan R, Bowen NJ, Chaudhary J. Inhibitor of differentiation 4 (ID4) inactivation promotes de novo steroidogenesis and castration resistant prostate cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2014:me20141100. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma P, Chinaranagari S, Patel D, Carey J, Chaudhary J. Epigenetic inactivation of inhibitor of differentiation 4 (Id4) correlates with prostate cancer. Cancer Med. 2012;1(2):176–186. doi: 10.1002/cam4.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel D, Chaudhary J. Increased expression of bHLH transcription factor E2A (TCF3) in prostate cancer promotes proliferation and confers resistance to doxorubicin induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;422(1):146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma P, Patel D, Chaudhary J. Id1 and Id3 expression is associated with increasing grade of prostate cancer: Id3 preferentially regulates CDKN1B. Cancer Med. 2012;1(2):187–197. doi: 10.1002/cam4.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prabhu S, Ignatova A, Park ST, Sun XH. Regulation of the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 by E2A and Id proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(10):5888–5896. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Asirvatham AJ, Schmidt MA, Chaudhary J. Non-redundant inhibitor of differentiation (Id) gene expression and function in human prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 2006;66(9):921–935. doi: 10.1002/pros.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pesce S, Benezra R. The loop region of the helix-loop-helix protein Id1 is critical for its dominant negative activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(12):7874–7880. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dahlman A, Edsjo A, Hallden C, Persson JL, Fine SW, Lilja H, Gerald W, Bjartell A. Effect of androgen deprivation therapy on the expression of prostate cancer biomarkers MSMB and MSMB-binding protein CRISP3. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2010;13(4):369–375. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chou PY, Fasman GD. Empirical predictions of protein conformation. Annual review of biochemistry. 1978;47:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun XH, Baltimore D. An inhibitory domain of E12 transcription factor prevents DNA binding in E12 homodimers but not in E12 heterodimers. Cell. 1991;64(2):459–470. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90653-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen CP, Kadesch T. B-cell-specific DNA binding by an E47 homodimer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(8):4518–4524. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coppe JP, Smith AP, Desprez PY. Id proteins in epithelial cells. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285(1):131–145. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yokota Y, Mori S. Role of Id family proteins in growth control. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190(1):21–28. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soroceanu L, Murase R, Limbad C, Singer E, Allison J, Adrados I, Kawamura R, Pakdel A, Fukuyo Y, Nguyen D, Khan S, Arauz R, Yount GL, Moore DH, Desprez P-Y, McAllister SD. Id-1 Is a Key Transcriptional Regulator of Glioblastoma Aggressiveness and a Novel Therapeutic Target. Cancer Research. 2013;73(5):1559–1569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taniguchi H, Jacinto FV, Villanueva A, Fernandez AF, Yamamoto H, Carmona FJ, Puertas S, Marquez VE, Shinomura Y, Imai K, Esteller M. Silencing of Kruppel-like factor 2 by the histone methyltransferase EZH2 in human cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31(15):1988–1994. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vinarskaja A, Goering W, Ingenwerth M, Schulz WA. ID4 is frequently downregulated and partially hypermethylated in prostate cancer. World journal of urology. 2012;30(3):319–325. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0750-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ling MT, Wang X, Lee DT, Tam PC, Tsao SW, Wong YC. Id-1 expression induces androgen-independent prostate cancer cell growth through activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(4):517–525. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Loveys DA, Streiff MB, Kato GJ. E2A basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factors are negatively regulated by serum growth factors and by the Id3 protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24(14):2813–2820. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.14.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rahme GJ, Israel MA. Id4 suppresses MMP2-mediated invasion of glioblastoma-derived cells by direct inactivation of Twist1 function. Oncogene. 2014 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zalmas LP, Zhao X, Graham AL, Fisher R, Reilly C, Coutts AS, La Thangue NB. DNA-damage response control of E2F7 and E2F8. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(3):252–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lingbeck JM, Trausch-Azar JS, Ciechanover A, Schwartz AL. E12 and E47 modulate cellular localization and proteasome-mediated degradation of MyoD and Id1. Oncogene. 2005;24(42):6376–6384. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bounpheng MA, Dimas JJ, Dodds SG, Christy BA. Degradation of Id proteins by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Faseb J. 1999;13(15):2257–2264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fairman R, Beran-Steed RK, Anthony-Cahill SJ, Lear JD, Stafford WF, DeGrado WF, Benfield PA, Brenner SL. Multiple oligomeric states regulate the DNA binding of helix-loop-helix peptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90(22):10429–10433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wibley J, Deed R, Jasiok M, Douglas K, Norton J. A homology model of the Id-3 helix-loop-helix domain as a basis for structure-function predictions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1294(2):138–146. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(96)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kiewitz SD, Cabrele C. Synthesis and conformational properties of protein fragments based on the Id family of DNA-binding and cell-differentiation inhibitors. Biopolymers. 2005;80(6):762–774. doi: 10.1002/bip.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amiel J, Trochet D, Clément-Ziza M, Munnich A, Lyonnet S. Polyalanine expansions in human. Human Molecular Genetics. 2004;13(suppl 2):R235–R243. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pelassa I, Cora D, Cesano F, Monje FJ, Montarolo PG, Fiumara F. Association of polyalanine and polyglutamine coiled coils mediates expansion disease-related protein aggregation and dysfunction. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(13):3402–3420. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bedford L, Walker R, Kondo T, van Cruchten I, King ER, Sablitzky F. Id4 is required for the correct timing of neural differentiation. Dev Biol. 2005;280(2):386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen H, Weng YC, Schatteman GC, Sanders L, Christy RJ, Christy BA. Expression of the dominant-negative regulator Id4 is induced during adipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256(3):614–619. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kondo T, Raff M. The Id4 HLH protein and the timing of oligodendrocyte differentiation. Embo J. 2000;19(9):1998–2007. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tokuzawa Y, Yagi K, Yamashita Y, Nakachi Y, Nikaido I, Bono H, Ninomiya Y, Kanesaki-Yatsuka Y, Akita M, Motegi H, Wakana S, Noda T, Sablitzky F, Arai S, Kurokawa R, Fukuda T, Katagiri T, Schonbach C, Suda T, Mizuno Y, Okazaki Y. Id4, a new candidate gene for senile osteoporosis, acts as a molecular switch promoting osteoblast differentiation. PLoS genetics. 2010;6(7):e1001019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Andres-Barquin PJ, Hernandez MC, Israel MA. Id4 expression induces apoptosis in astrocytic cultures and is down-regulated by activation of the cAMP-dependent signal transduction pathway. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247(2):347–355. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sikder HA, Devlin MK, Dunlap S, Ryu B, Alani RM. Id proteins in cell growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(6):525–530. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ciarrocchi A, Jankovic V, Shaked Y, Nolan DJ, Mittal V, Kerbel RS, Nimer SD, Benezra R. Id1 restrains p21 expression to control endothelial progenitor cell formation. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Henke E, Perk J, Vider J, de Candia P, Chin Y, Solit DB, Ponomarev V, Cartegni L, Manova K, Rosen N, Benezra R. Peptide-conjugated antisense oligonucleotides for targeted inhibition of a transcriptional regulator in vivo. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26(1):91–100. doi: 10.1038/nbt1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mern DS, Hasskarl J, Burwinkel B. Inhibition of Id proteins by a peptide aptamer induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(8):1237–1244. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mern D, Hoppe-Seyler K, Hoppe-Seyler F, Hasskarl J, Burwinkel B. Targeting Id1 and Id3 by a specific peptide aptamer induces E-box promoter activity, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010;124(3):623–633. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0810-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garland W, Benezra R, Chaudhary J. Targeting Protein–Protein Interactions to Treat Cancer—Recent Progress and Future Directions. In: Manoj CD, editor. Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Vol. 48. Academic Press; 2013. pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chinaranagari S, Sharma P, Chaudhary J. EZH2 dependent H3K27me3 is involved in epigenetic silencing of ID4 in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(16):7172–7182. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]