Abstract

AIM: To compare the outcomes of hand-sewn (HS) and linearly stapled (LS) esophagogastric anastomosis for esophageal cancer.

METHODS: Before beginning this study, a rigorous protocol was established according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration. Databases and references were searched for all randomized controlled trials and comparative clinical studies that compared LS with HS esophagogastric anastomosis for esophageal cancer. The primary outcomes compared were anastomotic leak and stricture. Subgroup analyses were performed according to site of anastomosis.

RESULTS: Fifteen studies were used, comprising 3203 patients (n = 2027 LS and 1176 HS). Primary outcome analysis revealed a significant decrease in anastomotic leakage (RR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.41-0.65; P < 0.00001) associated with LS anastomosis. A significantly reduced rate of anastomotic stricture associated with LS was also found (RR = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.49-0.64; P < 0.00001). A subgroup analysis according to the site of anastomosis revealed a significantly reduced rate of anastomotic stricture (P < 0.00001). Although there was no significant difference in the decrease in thoracic anastomotic leakage, there was a significant decrease in cervical anastomotic leakage associated with LS (P < 0.00001).

CONCLUSION: This meta-analysis indicates that the LS technique contributes to a reduced rate of leakage and stricture compared with the HS method.

Keywords: Anastomotic leakage, Anastomotic stricture, Hand-sewn anastomosis, Linearly stapled anastomosis, Meta-analysis

Core tip: This is an important meta-analysis comparing the results of hand-sewn and linear stapling techniques for esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal cancer resection. Primary outcome analysis revealed statistically significant decreases in anastomotic leakage and stricture associated with linearly stapled anastomosis. Subgroup analyses were performed according to site of anastomosis. This meta-analysis may offer some specific suggestions for esophagogastric anastomosis.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal carcinoma is a multifaceted and complex disease of rapidly rising incidence that exerts an increasing social and financial burden on global healthcare systems[1-3]. Esophagogastrectomy is the standard treatment for esophageal carcinoma and end-stage benign esophageal disease; however, the techniques of esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy are complex and associated with postoperative complications, such as anastomotic leakage and stricture. Such complications are frequently encountered and compromise quality of life, and they can even be life threatening. Both of these complications are prevalent and serious following esophagectomy; therefore, the method used for anastomosis has been the focus of much attention.

Esophagogastric anastomosis is divided into two methods: hand-sewn (HS) and linearly stapled (LS). Mechanical staplers have been widely used in esophagogastric anastomosis for their convenience and being less operator-dependent. Generally, two different types of staplers are widely used: the circular and linear. Some studies have observed that the use of a circular stapler contributes to reduced leakage, but is associated with increased risk of anastomotic strictures[4-10]. Anastomosis using LS, which was described by Collard et al[11] and modified by Orringer et al[12], is considered a major advance in reducing the incidence of anastomotic leakage and stricture. Several studies have reported that this technique is associated with reduced anastomotic complications.

Several studies have been performed to compare the traditional HS anastomosis method to the modern LS technique; however, which technique is superior remains controversial. To the best of our knowledge, no meta-analysis has compared LS with HS esophagogastric anastomosis for esophageal cancer; therefore, we pooled analyses of 15 studies from 1998 to 2013 and compared the contribution of each technique to the occurrence of postoperative anastomotic strictures and leakage. Meanwhile, we performed a subgroup analysis based on the site of anastomosis. This is believed to be the first meta-analysis comparing LS to HS esophagogastric anastomosis for esophageal cancer. We believe that this meta-analysis will provide information on treatment options for clinicians regarding esophageal reconstruction approaches after esophagectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

A systematic literature search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Chinese Biomedical Database, and Chinese Scientific Journals Database was conducted. The search terms were as follows: esophagectomy, anastomosis, esophagus, linear, side-to-side, hand-sewn, manual, stapled, mechanical, and gastric, and the medical subject headings anastomosis, linear stapled, side-to-side, hand-sewn, manual, stapled, mechanical, and esophagectomy were used in combination with the Boolean operators “and” or “or”. The electronic search was supplemented by a hard-copy search of published abstracts from conference proceedings, including the International Society for Esophagus Diseases, the China Esophageal Society Meeting, United European Gastroenterology Week, and some surgery associations. We also scanned lists of trials that were selected from electronic searches to distinguish further relevant trials.

Before the beginning of this study, a rigorous protocol was established according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration. Abstracts of the citations identified by the search were then scrutinized by two observers to determine eligibility for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Studies were included if they met all the following criteria: (1) comparative studies; (2) separation into groups based on the use of LS and HS esophagogastrostomy for esophageal surgery; and (3) an outcome of anastomotic leakage or strictures. Exclusion criteria were: letters to the editor, reviews, and clinical trials without the two groups (LS vs, HS anastomosis).

For the purposes of this study, we considered patients to have experienced an anastomotic leak when the following were indicated: (1) positive contrast study with or without clinical signs; and (2) clinical signs alone requiring subsequent alteration in clinical care (e.g., wound drainage and packing, or reoperation). Patients were considered to have postoperative strictures, and a need for postoperative dilatation, if they experienced any dysphagia and required more than one dilatation in the first six months after surgery. In support of the diagnosis, anastomotic narrowing was noted at the time of endoscopy and dysphagia was typically relieved after dilatation. Data from eligible trials were entered into a computerized spreadsheet for analysis. The quality of each trial was assessed using the Jadad scoring system[13].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by the RevMan 5.2.9 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom) for the controlled studies. The data extracted from the relevant trials were combined and the relative risk (RR) was calculated with 95%CI. Statistical heterogeneity among the trials was evaluated using Cochran’s Q test (χ2 test) and the Higgins I2 statistic to determine the percentage of total variations among studies resulting from heterogeneity. If the I2 statistic was ≤ 50%, the fixed effects model was used to pool studies; if not, the random effects model was used.

RESULTS

Characteristics of included trials

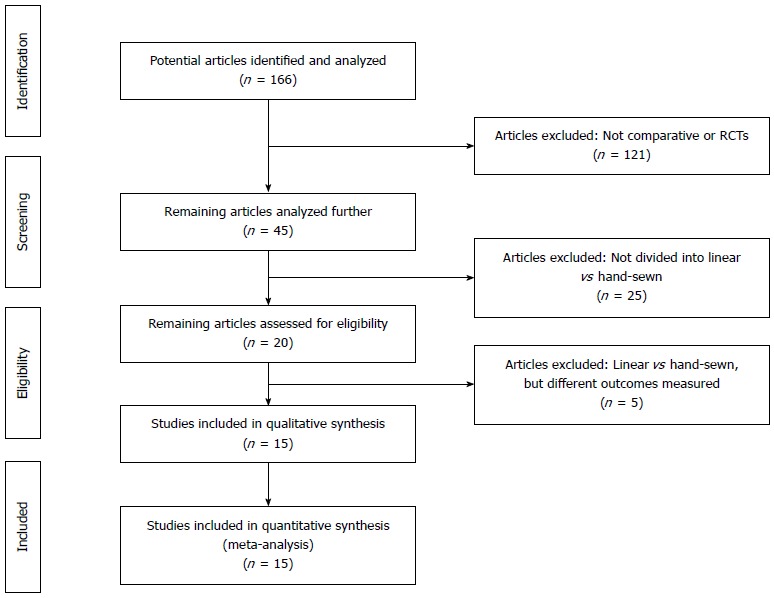

Fifteen documents were included comprising 3203 patients (n = 2027 LS and n = 1176 HS)[11,12,14-25]. Patient demographic data for each trial are presented in Table 1. A PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1) describes the details of the literature search for this systematic review.

Table 1.

Demographic data n (%)

| Ref. | Study type | Anastomotic site |

Patient |

Leakage |

Stricture |

Sutured layer in HS | |||

| LS | HS | LS | HS | LS | HS | ||||

| Collard et al[11], 1998 | Comparative | Cervical | 16 | 24 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) | 11 (45.8) | Single |

| Orringer et al[12], 2000 | Comparative | Cervical | 111 | 112 | 3 (2.7) | 16 (14.3) | 39 (35.1) | 54 (48.2) | NS |

| Singh et al[14], 2001 | Comparative | Cervical | 16 | 43 | 1 (6.3) | 10 (23.3) | 3 (18.8) | 25 (58.1) | Single |

| Casson et al[15], 2002 | Comparative | Cervical | 38 | 53 | 3 (7.9) | 12 (22.6) | 3 (7.9) | 9 (17.0) | Mixed |

| Behzadi et al[16], 2005 | Comparative | NS | 75 | 205 | 4 (5.3) | 26 (12.7) | 11 (14.7) | 70 (34.1) | Mixed |

| Ercan et al[7], 2005 | Comparative | Cervical | 86 | 188 | 3 (3.5) | 20 (10.6) | 56 (65.1) | 169 (89.9) | Single |

| Blackmon et al[17], 2007 | Comparative | Thoracic | 44 | 23 | 3 (6.8) | 1 (4.3) | 4 (9.0) | 8 (34.8) | Double |

| Kondra et al[18], 2008 | Comparative | Cervical | 79 | 89 | 10 (12.7) | 24 (27.0) | 23 (29.1) | 49 (55.1) | Double |

| Cooke et al[19], 2009 | Comparative | Cervical | 974 | 159 | 117 (12.0) | 33 (20.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Deng et al[20], 2009 | Comparative | Cervical | 9 | 8 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (50.0) | Single |

| Xu et al[21], 2011 | Comparative | Thoracic | 166 | 54 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.8) | 5 (9.3) | NS |

| Saluja et al[22], 2012 | RCT | Cervical | 87 | 87 | 16 (18.4) | 14 (16.1) | 7 (8.0) | 17 (19.5) | Single |

| Yang et al[23], 2012 | RCT | Cervical | 21 | 22 | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.6) | Double |

| Wang et al[24], 2013 | RCT | Thoracic | 45 | 52 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.6) | Single |

| Price et al[25], 2013 | Comparative | Mixed | 260 | 57 | 21 (8.1) | 11 (19.3) | 33 (12.7) | 13 (22.8) | NS |

HS: Hand-sewn; LS: Linear stapled; NS: Not specified; RCT: Randomized controlled trial.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the literature search according to PRISMA statement. RCTs: Randomized controlled trials.

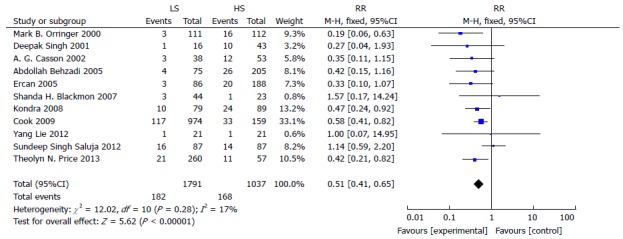

Gastroesophageal anastomotic leakage

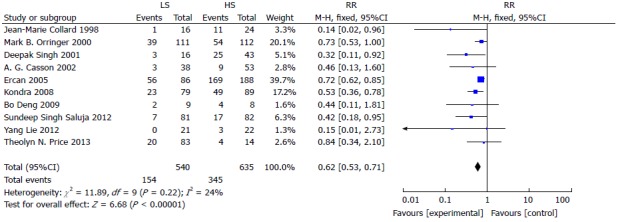

Eleven studies reported the incidence of gastroesophageal anastomotic leakage following LS or HS anastomosis. The analysis found a significant difference between the LS and HS method in reducing the incidence of gastroesophageal anastomotic leakage (RR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.41-0.65; P < 0.00001) (Figure 2). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 17%, χ2 = 12.02, df = 10; P = 0.28). A subgroup analysis for anastomotic leakage was conducted according to the site of anastomosis. The reduction in RR for cervical anastomotic leakage was significant at 0.49 with 95%CI: 0.39-0.63 (P < 0.00001) (Figure 3), but no differences were found in thoracic anastomotic leakage associated with LS (RR = 1.32, 95%CI: 0.39-4.50; P = 0.66) (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Forest plot for anastomotic leakage. HS: Hand-sewn; LS: Linearly stapled.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis for cervical leakage. HS: Hand-sewn; LS: Linearly stapled.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis for thoracic leakage. HS: Hand-sewn; LS: Linearly stapled.

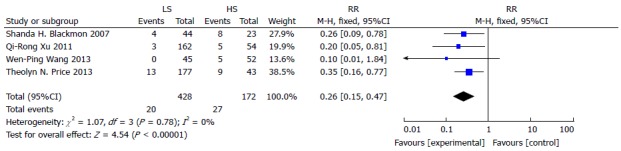

Gastroesophageal anastomotic stricture

Fourteen studies reported the incidence of gastroesophageal anastomotic stricture following LS and HS anastomosis. The use of LS had a reduced risk of anastomotic stricture compared to that of HS (RR = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.49-0.64; P < 0.00001) (Figure 5). Statistical heterogeneity was not detected (I2 = 44%, χ2 = 23.09, df = 13, P = 0.04). A subgroup analysis of anastomotic stricture was conducted according to site of anastomosis. There was a significant reduction in anastomotic stricture in the neck (RR = 0.62, 95%CI: 0.53-0.71, P < 0.00001) (Figure 6) and thorax (RR = 0.26, 95%CI: 0.15-0.47; P < 0.00001) (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Forest plot for anastomotic strictures. HS: Hand-sewn; LS: Linearly stapled.

Figure 6.

Subgroup analysis for cervical stricture. HS: Hand-sewn; LS: Linearly stapled.

Figure 7.

Subgroup analysis for thoracic stricture. HS: Hand-sewn; LS: Linearly stapled.

DISCUSSION

In the early days, the rate of successful HS anastomosis was low. As anastomosis technology progressed, the success rate increased, and when LS was developed, the success rates were even higher. LS anastomosis was first described by Collard et al[11] in 1998 and modified by Orringer et al[12], who performed side-to-side esophagogastric anastomosis with a small linear stapler LS anastomosis or with a side-to-side orientation, which improved postoperative outcomes after esophagogastric anastomosis.

LS is structured using two double-staggered rows of staples and can be cut between the double rows simultaneously. In the LS suture technique, the two forks of an Endo-GIA stapler are placed across the two opposing walls with the anvil in the gastric lumen and the staple cartridge in the esophageal lumen. After approximation of the two forks, the trigger of the stapler is squeezed to allow forward displacement of the knife and the delivery of three rows of staples on each side. After the two forks have been separated, the stapler is removed and the two stapled wound edges are naturally retracted laterally from the intramural musculature. The medial slit thus becomes a V-shaped opening between the two lumina. The two posterior walls realign themselves by exerting gentle downward traction on the transplant. The anterior walls are sutured to each other using a single-layer running-suture technique similar to that used in HS anastomosis or using a linear stapler.

The aim of this meta-analysis was to compare the main clinical outcomes following LS and HS esophagogastric anastomosis, including the rates of anastomotic leakage and stricture. Many local and systemic factors, such as the absence of serosa and longitudinal orientation of muscle fibers, influence the process of wound healing and incidence of anastomotic leakage. Among these factors, the surgical anastomotic technique remains an important variable that can be modified. Compared with HS, LS esophagogastric anastomosis has a lower rate of anastomosis leakage for several possible reasons: (1) the stapled anastomoses are considered to be more expedient and less traumatic to tissues; (2) the lateral stay sutures allow for reduced tension on the anastomosis without compromising gastric conduit microcirculation; and (3) LS provides triple-layered staple construction that is less traumatic and more watertight than HS. It has been reported that the incidence of esophagogastric anastomosis leakage with the LS technique in cervical anastomosis varies between 15% and 25%, which is more frequent than in thoracic anastomosis[26]. Therefore, the superiority of the LS technique in reducing the rate of leakage is more substantial in cervical anastomosis than in thoracic anastomosis.

In terms of anastomotic stricture, LS is superior to HS (RR = 0.54; 95%CI: 0.47-0.63; P < 0.00001). This trend was consistent in all subgroup analyses, and the between-study heterogeneity was found to be small. Such results are possible because LS anastomosis provides a larger cross-sectional area of esophagogastrostomy, which could reduce strictures and the subsequent need for later dilatation.

The meta-analysis presented here demonstrates that LS esophagogastric anastomosis can be performed safely with decreasing rates of both leakage and stricture compared to those of HS anastomosis. Subgroup analyses revealed that regardless of whether the surgery site was cervical or thoracic, LS can greatly decrease anastomotic stricture compared to HS. Furthermore, LS can reduce the rate of cervical anastomotic leakage.

For this study, we attempted to follow closely the Cochrane Collaboration recommendations. A rigorous study protocol was pre-specified and several electronic databases, references for relevant trials, and international conference abstracts were searched without restrictions on language. The 15 studies included for this pooled analysis comprised 12 comparative studies and three randomized controlled trials. Although the current review makes a strong argument for the use of the LS anastomotic technique after esophagectomy, there are inherent weaknesses associated with this study. Most of the studies in this meta-analysis were not randomized controlled trials; therefore, bias might exist.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis of the adoption of an LS anastomotic technique for esophagogastric anastomoses in esophagectomy for cancer indicates that the new technique lowers anastomotic leakage and stricture rates compared to traditionally used HS techniques. Furthermore, the application of the LS technique is usually easy and standardized such that the incidence of technical errors is minimized. In contrast, the HS method requires surgical expertise and might not be practical everywhere; therefore, we should preferentially use LS over the HS method. We believe that this meta-analysis can provide information about treatment options for clinicians regarding reconstruction using a gastric tube after esophagectomy.

COMMENTS

Background

Currently, the standard treatment for esophageal cancer continues to be esophagectomy. Hand-sewn (HS) and linear stapler (LS) anastomosis are two major methods for esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy. However, which technique is superior remains controversial. This meta-analysis compared the outcomes using the HS and LS methods for esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy by pooling all data from relevant randomized controlled trials and comparative clinical studies, to reach a consensus for comparison of two esophagogastric anastomosis methods.

Research frontiers

Several studies have been performed to compare the traditional HS anastomosis method to the modern LS technique; however, which technique is superior remains controversial. To date, no meta-analysis has compared LS with HS esophagogastric anastomosis for esophageal cancer.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In this meta-analysis, primary outcome analysis revealed a significant decrease in anastomotic leakage associated with LS anastomosis. A significantly reduced rate of anastomotic stricture associated with LS was also found. A subgroup analysis according to the site of anastomosis revealed a significantly reduced rate of anastomotic stricture. Although there were no significant differences in the decrease in thoracic anastomotic leakage, there was a significant decrease in cervical anastomotic leakage associated with the LS technique. This meta-analysis provides some information on treatment options for clinicians regarding reconstruction using a gastric tube after esophagectomy.

Applications

This meta-analysis indicates that the LS technique contributes to a reduced rate of both anastomotic leakage and stricture compared with the HS method; therefore, the LS technique should be the recommended preferential technique for esophageal anastomosis.

Terminology

HS anastomosis is esophagogastric anastomosis performed by hand with interrupted absorbable monofilament sutures. LS anastomosis means that the esophagogastric anastomosis is performed using linear staplers.

Peer-review

This meta-analysis addresses an important question for esophagogastric surgeons. This is a nicely written manuscript and the analyses seem to be well performed. The topic of the esophagogastric anastomosis is not really new, but it is still one of the mainly important problems in esophageal surgery.

Footnotes

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: July 28, 2014

First decision: September 15, 2014

Article in press: December 8, 2014

P- Reviewer: Bintintan VV, Chiu CC, Huang XB S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albiñana V, Recio-Poveda L, Zarrabeitia R, Bernabéu C, Botella LM. Propranolol as antiangiogenic candidate for the therapy of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:41–53. doi: 10.1160/TH11-11-0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fok M, Ah-Chong AK, Cheng SW, Wong J. Comparison of a single layer continuous hand-sewn method and circular stapling in 580 oesophageal anastomoses. Br J Surg. 1991;78:342–345. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law S, Fok M, Chu KM, Wong J. Comparison of hand-sewn and stapled esophagogastric anastomosis after esophageal resection for cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 1997;226:169–173. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199708000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walther B, Johansson J, Johnsson F, Von Holstein CS, Zilling T. Cervical or thoracic anastomosis after esophageal resection and gastric tube reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial comparing sutured neck anastomosis with stapled intrathoracic anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:803–812; discussion 812-814. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098624.04100.b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ercan S, Rice TW, Murthy SC, Rybicki LA, Blackstone EH. Does esophagogastric anastomotic technique influence the outcome of patients with esophageal cancer? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worrell S, Mumtaz S, Tsuboi K, Lee TH, Mittal SK. Anastomotic complications associated with stapled versus hand-sewn anastomosis. J Surg Res. 2010;161:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markar SR, Karthikesalingam A, Vyas S, Hashemi M, Winslet M. Hand-sewn versus stapled oesophago-gastric anastomosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:876–884. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honda M, Kuriyama A, Noma H, Nunobe S, Furukawa TA. Hand-sewn versus mechanical esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;257:238–248. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826d4723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collard JM, Romagnoli R, Goncette L, Otte JB, Kestens PJ. Terminalized semimechanical side-to-side suture technique for cervical esophagogastrostomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:814–817. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Eliminating the cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leak with a side-to-side stapled anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;119:277–288. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh D, Maley RH, Santucci T, Macherey RS, Bartley S, Weyant RJ, Landreneau RJ. Experience and technique of stapled mechanical cervical esophagogastric anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:419–424. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casson AG, Porter GA, Veugelers PJ. Evolution and critical appraisal of anastomotic technique following resection of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:296–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2002.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behzadi A, Nichols FC, Cassivi SD, Deschamps C, Allen MS, Pairolero PC. Esophagogastrectomy: the influence of stapled versus hand-sewn anastomosis on outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1031–1040; discussion 1040-1042. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackmon SH, Correa AM, Wynn B, Hofstetter WL, Martin LW, Mehran RJ, Rice DC, Swisher SG, Walsh GL, Roth JA, et al. Propensity-matched analysis of three techniques for intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1805–1813; discussion 1813. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondra J, Ong SR, Clifton J, Evans K, Finley RJ, Yee J. A change in clinical practice: a partially stapled cervical esophagogastric anastomosis reduces morbidity and improves functional outcome after esophagectomy for cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:422–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooke DT, Lin GC, Lau CL, Zhang L, Si MS, Lee J, Chang AC, Pickens A, Orringer MB. Analysis of cervical esophagogastric anastomotic leaks after transhiatal esophagectomy: risk factors, presentation, and detection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:177–184; discussion 184-185. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng B, Wang RW, Jiang YG, Tan QY, Zhao YP, Zhou JH, Liao XL, Ma Z. Functional and menometric study of side-to-side stapled anastomosis and traditional hand-sewn anastomosis in cervical esophagogastrostomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu QR, Wang KN, Wang WP, Zhang K, Chen LQ. Linear stapled esophagogastrostomy is more effective than hand-sewn or circular stapler in prevention of anastomotic stricture: a comparative clinical study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:915–921. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saluja SS, Ray S, Pal S, Sanyal S, Agrawal N, Dash NR, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Randomized trial comparing side-to-side stapled and hand-sewn esophagogastric anastomosis in neck. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1287–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang L, Zheng YF, Jiang JQ, Yu YK, Li W, Zheng XS. Comparison of esophagogastric side-to-side anastomosis and hand-sewn end-to-side anastomosis in neck. Chongqing Medicine. 2012;41:3155–3156. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang WP, Gao Q, Wang KN, Shi H, Chen LQ. A prospective randomized controlled trial of semi-mechanical versus hand-sewn or circular stapled esophagogastrostomy for prevention of anastomotic stricture. World J Surg. 2013;37:1043–1050. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1932-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price TN, Nichols FC, Harmsen WS, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, Wigle DA, Shen KR, Deschamps C. A comprehensive review of anastomotic technique in 432 esophagectomies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:1154–1160; discussion 1160-1161. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orringer MB, Marshall B, Iannettoni MD. Transhiatal esophagectomy: clinical experience and refinements. Ann Surg. 1999;230:392–400; discussion 400-403. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]