Summary

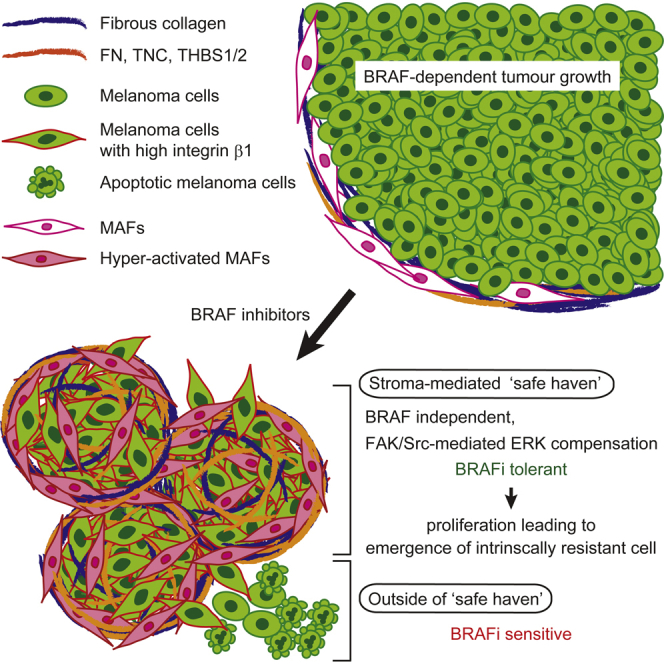

Intravital imaging of BRAF-mutant melanoma cells containing an ERK/MAPK biosensor reveals how the tumor microenvironment affects response to BRAF inhibition by PLX4720. Initially, melanoma cells respond to PLX4720, but rapid reactivation of ERK/MAPK is observed in areas of high stromal density. This is linked to “paradoxical” activation of melanoma-associated fibroblasts by PLX4720 and the promotion of matrix production and remodeling leading to elevated integrin β1/FAK/Src signaling in melanoma cells. Fibronectin-rich matrices with 3–12 kPa elastic modulus are sufficient to provide PLX4720 tolerance. Co-inhibition of BRAF and FAK abolished ERK reactivation and led to more effective control of BRAF-mutant melanoma. We propose that paradoxically activated MAFs provide a “safe haven” for melanoma cells to tolerate BRAF inhibition.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

BRAF mutant melanoma cells respond to PLX4720 heterogeneously in vivo

-

•

BRAF inhibition activates MAFs, leading to FAK-dependent melanoma survival signaling

-

•

ECM-derived signals can support residual disease

-

•

BRAF and FAK inhibition synergize in pre-clinical models

Hirata et al. show that the BRAF inhibitor PLX4720 promotes melanoma-associated fibroblasts in BRAF-mutant melanomas to produce and remodel matrix, leading to integrin β1-FAK-Src signaling and reactivation of ERK and MAPK in melanoma cells. Co-inhibition of BRAF and FAK blocks ERK reactivation.

Significance

Many tumors show an initial response to targeted therapies before genetic resistance emerges; however, little is known about how tumor cells might tolerate therapy before genetic resistance dominates. We show how BRAF-mutant melanoma cells rapidly become tolerant to PLX4720 in areas of high stroma. We demonstrate that PLX4720 has an effect on the tumor stroma, leading to enhanced matrix remodeling. The remodeled matrix then provides signals that enable melanoma cells to tolerate PLX4720. We propose that this safe haven enhances the population of cancer cells from which genetic resistance emerges. This work highlights the need to consider the effects of targeted therapies on the tumor microenvironment.

Introduction

Since the discovery of oncogenes that encoded protein kinases, it has been hoped that inhibition of the relevant kinases would be an effective chemotherapeutic strategy (Shawver et al., 2002). This aspiration has become a clinical reality with the development of inhibitors against Abl tyrosine kinase (Druker et al., 2001, 2006), EGFR family kinases (Maemondo et al., 2010; Mok et al., 2009; Sordella et al., 2004), and BRAF (Chapman et al., 2011; Flaherty et al., 2010; Sosman et al., 2012). However, agents targeting either EGFR or BRAF typically show good efficacy in tumors with matching oncogenic mutations for a number of months before genetically resistant cells dominate the tumor and the therapy fails (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Nazarian et al., 2010; Poulikakos et al., 2011; Poulikakos and Rosen, 2011; Villanueva et al., 2011). In the case of EGFR-mutant lung tumors, it has been shown that resistant cells may be present even before treatment and that these are at a strong selective advantage during therapy (Inukai et al., 2006; Maheswaran et al., 2008; Rosell et al., 2011; Turke et al., 2010). However, the situation in BRAF-mutant melanoma treated with BRAF inhibitors is less clear. There is significant variability in the magnitude of initial response to BRAF inhibition (Chapman et al., 2011; Sosman et al., 2012) and genetically resistant sub-clones have not been detected prior to treatment in tumors that show modest responses. It has been proposed that non-cell autonomous mechanisms involving HGF production by the tumor stroma may drive resistance (Straussman et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2012). However, it is not clear how selective pressure would act on the genetically stable stroma to promote the emergence of resistant disease.

Establishing the chronology of biochemical responses to targeted therapy and biological changes elicited within the context of complex tumor microenvironments remains challenging. BRAF exerts its effects through activation of ERK/MAPK signaling. The activity of ERK/MAPK can be monitored in live tissue using a biosensor construct containing two fluorophores, a long flexible linker, an ERK/MAP kinase binding site, an optimal substrate site for the kinase, and a phospho-threonine binding domain (Harvey et al., 2008; Komatsu et al., 2011). When the substrate site is phosphorylated, it engages in an intra-molecular interaction with the phospho-threonine binding domain, leading to an overall change in the conformation of the molecule and a change in fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between the two fluorophores (Komatsu et al., 2011). This system enables the biochemical response to BRAF inhibition to be monitored with single cell resolution in vivo. Genetically engineered syngeneic hosts additionally provide the ability to depict the tumor stroma (Muzumdar et al., 2007). These technologies can be combined with intravital imaging windows to longitudinally track both the biochemical response to BRAF inhibition and the distribution of the tumor stroma (Janssen et al., 2013).

Results

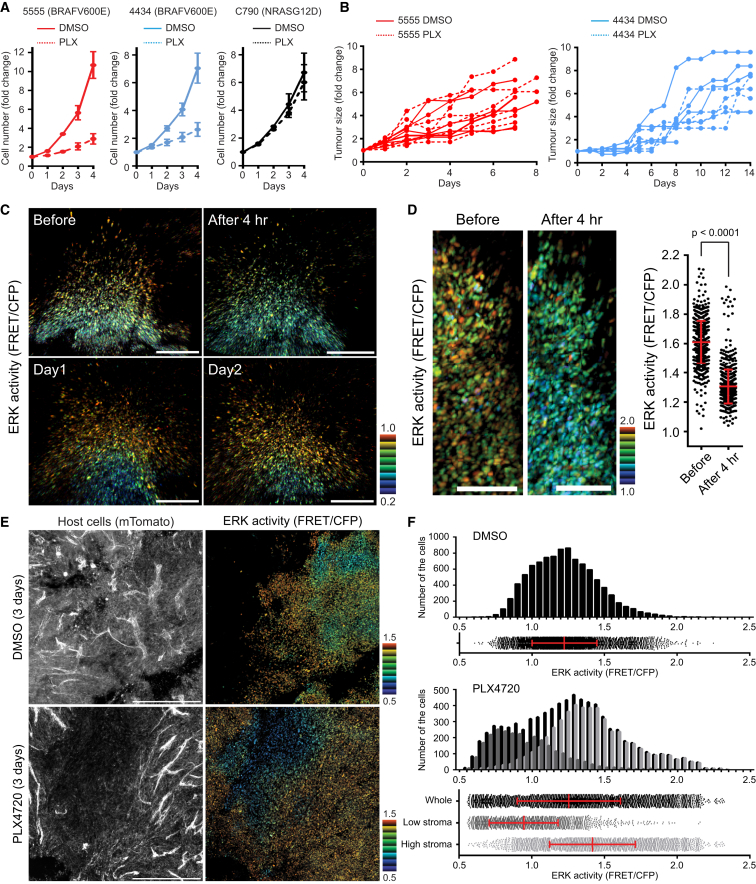

In Vivo Model of Extrinsic Resistance to BRAF Inhibition

To study responses to BRAF inhibition in a syngeneic tumor microenvironment, we tested the response of BRAF and NRAS mutant C57/BL6 mouse melanoma cell lines to the BRAF inhibitor PLX4720. Two different BRAF mutant lines, 5555 and 4434, were sensitive to PLX4720 whereas, as expected, the NRAS mutant cells (C790) were refractory to PLX4720 in vitro (Figure 1A). We next tested the response of these cells to PLX4720 when growing as tumors in syngeneic mice. To our surprise, both BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines were refractory to PLX4720 (Figure 1B). This unexpected result suggested to us that these cells might represent a model to probe non-cell autonomous mechanisms of resistance of PLX4720. Furthermore, they may represent the small subset of BRAF-mutant melanoma that exhibit only a small response to vemurafenib.

Figure 1.

Melanoma Cells Respond to PLX4720 Heterogeneously In Vivo

(A and B) Growth curves of the indicated melanoma cells in vitro (A) and in vivo (B) treated with DMSO (0.1% in vitro and 4% in vivo) or PLX4720 (1 μM in vitro and 25 mg/kg in vivo). Data in (A) are represented as mean ± SD.

(C and D) Intravital longitudinal imaging of 5555-EKAREV-NLS tumors through an imaging window. The mouse was gavaged PLX4720 (25 mg/kg) every 24 hr, and images were acquired before and 4 hr after the first, second (Day 1), and third (Day 2) gavage. ERK activities in (D) were quantified and shown as mean ± SD. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(E) Intravital images of 5555-EKAREV-NLS subcutaneously grown in C57BL/6_ROSA26-mTmG mice. Upper and lower images are from mice treated with DMSO and PLX4720 for 3 days, respectively. Left: all host cells (Tomato). Right: ERK activity in 5555 cells. Scale bars represent 500 μm.

(F) Distribution and histogram of ERK activity in control and PLX4720-treated mice. In PLX4720-treated mice, cells are separated into two groups according to the host cell density (low and high stroma) and analyzed.

Bars in the scatterplots indicate mean ± SD. See also Figure S1.

To understand the lack of response of 5555 and 4434 cells to PLX4720 in vivo, we reasoned that it would be important to monitor the BRAF signaling with single cell resolution. We engineered 5555 and 4434 cells to express an ERK/MAP kinase biosensor located in the nucleus—called EKAREV-NLS (Figure S1A). The EKAREV biosensor faithfully monitored changes in ERK/MAP kinase signaling in response to TPA and either BRAF or MEK inhibitors (Figures S1B–S1E). In contrast, “paradoxical” activation of ERK/MAPK activity is observed in NRAS mutant cells treated with PLX4720 (Figures S1C and S1F). We further confirmed that changes in FRET signal are absolutely dependent upon the phospho-acceptor site in the biosensor (Figures S1G and S1H).

We next generated tumors using 5555-EKAREV-NLS cells; in some cases, these were adjacent to titanium imaging windows that allow longitudinal imaging of the same tumor (Janssen et al., 2013). Intravital imaging revealed considerable heterogeneity in EKAREV FRET signal (Figures 1C–1F, S1I, and S1J). These data are supported by ppERK immunohistochemical analysis (Figure S1K). To gain insight into the lack of effect of PLX4720 on tumor growth, we performed longitudinal imaging of tumors before and during PLX4720 treatment. The results showed that the high EKAREV FRET signal was reduced 4 hr after administration of PLX4720 (Figures 1C and 1D). These data suggest that PLX4720 can access the tumor and achieve the reduction in ERK/MAPK activity expected based on the in vitro analysis in Figures S1C–S1E. However, within 1 day, high levels of EKAREV FRET signal returned even though PLX4720 was administered daily (Figure 1C). Analysis of the distribution of EKAREV signal after 3 days of PLX4720 treatment suggested that only a small proportion of 5555 cells show a stable reduction in ERK/MAPK activity (Figures 1E and 1F). These cells were typically located in regions with low levels of host cells, which were demonstrated based on of their expression of the mTomato transgene. To more robustly test this observation, we segmented images of PLX4720 treated tumors into regions with high or low levels of mTomato signal (Figure S1L). Figure 1F shows that regions with low levels of stromal cells had significantly lower levels EKAREV FRET signal (similar data were obtained in 4434 tumors; Figure S1M). These data demonstrate BRAF mutant 5555 and 4434 tumors show a short-lived biochemical response to PLX4720. Further, the rapid re-activation of ERK/MAPK and adaptation of these tumors to PLX4720 is correlated with stromal density.

Melanoma-Associated Fibroblasts Are Sufficient to Confer Tolerance to BRAF Inhibition

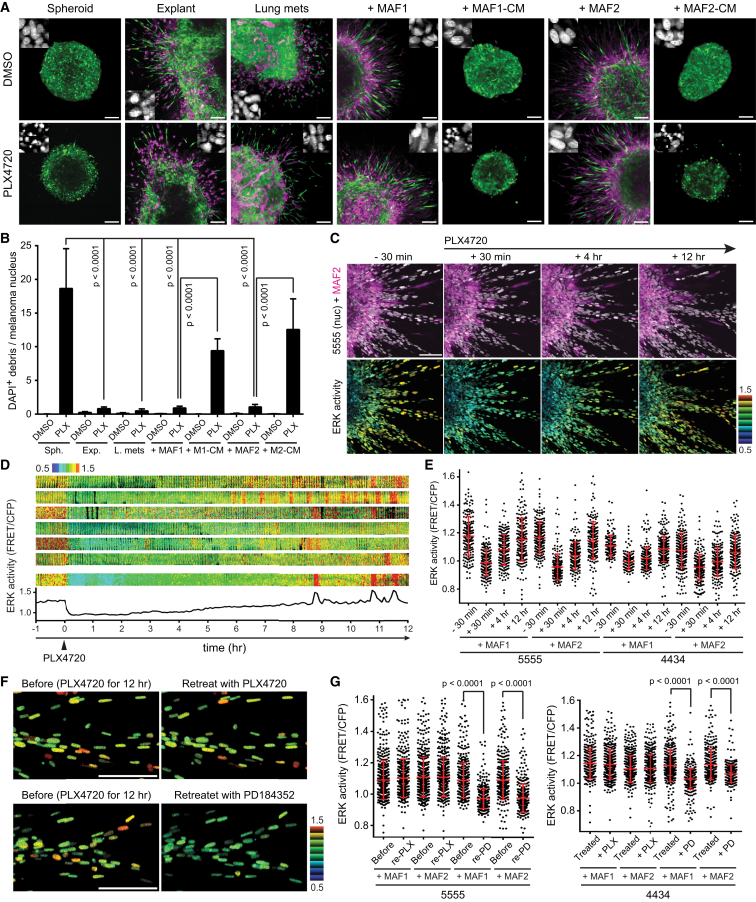

We sought to establish a culture system that re-capitulated the PLX4720 tolerance that we observed in vivo. The behavior of pure spheroids of melanoma cells was compared with that of equivalent sized tumor pieces when embedded in a collagen matrix. Figures 2A and 2B show that pure melanoma spheroids were highly sensitive to PLX4720, with the appearance of many nuclear fragments indicating cell death. In contrast, melanoma explants from either subcutaneous tumors or experimentally established lung metastases were unresponsive to PLX4720 (Figures 2A and 2B). Even in the presence of drug, melanoma cells retained healthy nuclear architecture and invasive capability. Thus, the spheroid model recapitulates the stroma-dependent PLX4720 tolerance observed in vivo. It also formally excludes any problems relating to drug access that might confound interpretation of the in vivo data.

Figure 2.

Stromal Cells Provide Invasive and Pro-survival Signals, and the System Adapts to the Drug Within 12 Hours

(A and B) Various types (indicated above in each panel) of 5555 melanoma spheroids/tumor explants were embedded into collagen gels and treated with 0.1% DMSO (upper panels) or 1 μM PLX4720 (lower panels) for 24 hr. 5555 cells are depicted in green, stromal cells/MAFs in magenta, and representative DAPI-stained images are also shown (A), and the ratio of DAPI-positive debris and melanoma nucleus was calculated as a cell death indicator (B). Spheroid, 5555 pure spheroids made in vitro; explant, tumor explants of 5555 grown subcutaneously in C57BL/6_ROSA26-mTmG mice; lung mets, tumor explants of experimentally-induced lung metastasis of 5555 in C57BL/6_ROSA26-mTmG mice; +MAF1/2, 5555 and MAF co-culture spheroid made in vitro; +MAF1/2-CM, 5555 spheroids made in vitro were treated with conditioned media from MAFs. Data in (B) are represented as mean ± SD. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(C–E) 5555/4434-EKAREV-NLS and MAF1/2-mCherry co-cultured spheroids were embedded in collagen gels and treated with PLX4720 (1 μM) at time = 0. Upper images in (C) indicate 5555 nuclei (gray) and MAF2 (magenta), and lower images indicate ERK activity (FRET/CFP) in 5555 cells. Kymographs of ERK activity in seven representative cells are shown in (D), and ERK activities at time −30 min, +30 min, +4 hr, and +12 hr are quantified and shown in (E) as scatterplots with mean ± SD. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

(F and G) 5555/4434-EKAREV-NLS and MAF1/2 co-cultured spheroids in collagen gels were treated with PLX4720 (1 μM) for 12 hr, followed by re-treatment with PLX4720 (1 μM) or PD184352 (1 μM). Representative images of 5555 co-cultured with MAF1 are shown in (F) and ERK activities (FRET/CFP) in 5555 and 4434 before and after re-treatment were quantified and shown as scatterplots with mean ± SD (G).

Scale bars represent 100 μm. See also Figure S2 and Movie S1.

We next sought to identify the stromal cell type that might be responsible for the adaptive behavior of 5555 and 4434 melanoma. Immunohistochemical staining of 5555 and 4434 tumors revealed low number of infiltrating lymphocytes and neutrophils, and there was no clear relationship between the location of blood vessels and ppERK signals (Figure S2A). However, both macrophages and stromal fibroblasts were abundant in both DMSO- and PLX4720-treated tumors (Figure S2A). We therefore explored whether melanoma-associated fibroblasts (MAFs) or macrophages might be sufficient to confer drug tolerance on melanoma cells. Two isolates of MAFs were established from patients (designated MAF1 and MAF2, Figures S2B and S2C) and their effect on the response of 5555 and 4434 cells to PLX4720 was tested. Figures 2A, 2B, and S2D show that co-culture of either MAF1 or MAF2 with melanoma cells conferred tolerance of PLX4720 and invasive behavior. This effect was significantly dependent on close proximity of the two cell types because MAF conditioned media had only partial ability to reduce PLX4720-induced cell death (Figures 2A, 2B, S2E, and S2F). Furthermore, we excluded a role for EGFR and c-Met in mediating MAF-dependent PLX4720 tolerance (Figures S2G and S2H). Co-culture with macrophages was unable to confer drug tolerance on melanoma cells (Figure S2I). These data establish fibroblastic stromal is sufficient to confer tolerance to PLX4720.

We next investigated the activity of ERK/MAPK signaling in melanoma spheroids. FRET imaging with EKAREV-NLS shows heterogeneous ERK activity in 5555 explants and 5555/MAF co-culture spheroids (Figure S2J, and similar results with 4434 cells in Figure S2K). There was markedly reduced signal/noise of the EKAR biosensor in the explant/spheroid center; therefore, we excluded these regions from our subsequent analyses. We performed time-lapse imaging of spheroid co-cultures before and after the addition of PLX4720. Figures 2C–2E and Movie S1 reveal a marked decrease in EKAREV signal 30 min after the addition of the drug. However, within 12 hr, the EKAREV signal had returned to the level prior to drug addition. This was similar to the in vivo results. In pure melanoma spheroids, the EKAREV signal was stably decreased until cells began to die (the variable FRET signal in apoptotic cultures cannot reliably be interpreted). To exclude the possibility of drug metabolism or drug degradation, we re-added PLX4720 after 12 hr and monitored the response. Strikingly, co-cultures that had been exposed to PLX4720 for 12 hr were completely refractory to the addition of more PLX4720, while importantly, they remained sensitive to the addition of the MEK inhibitor PD184352 (Figures 2F and 2G). These data demonstrate that co-cultures of melanoma cells and MAFs switch from BRAF-dependent ERK signaling to BRAF-independent ERK signaling in just 12 hr.

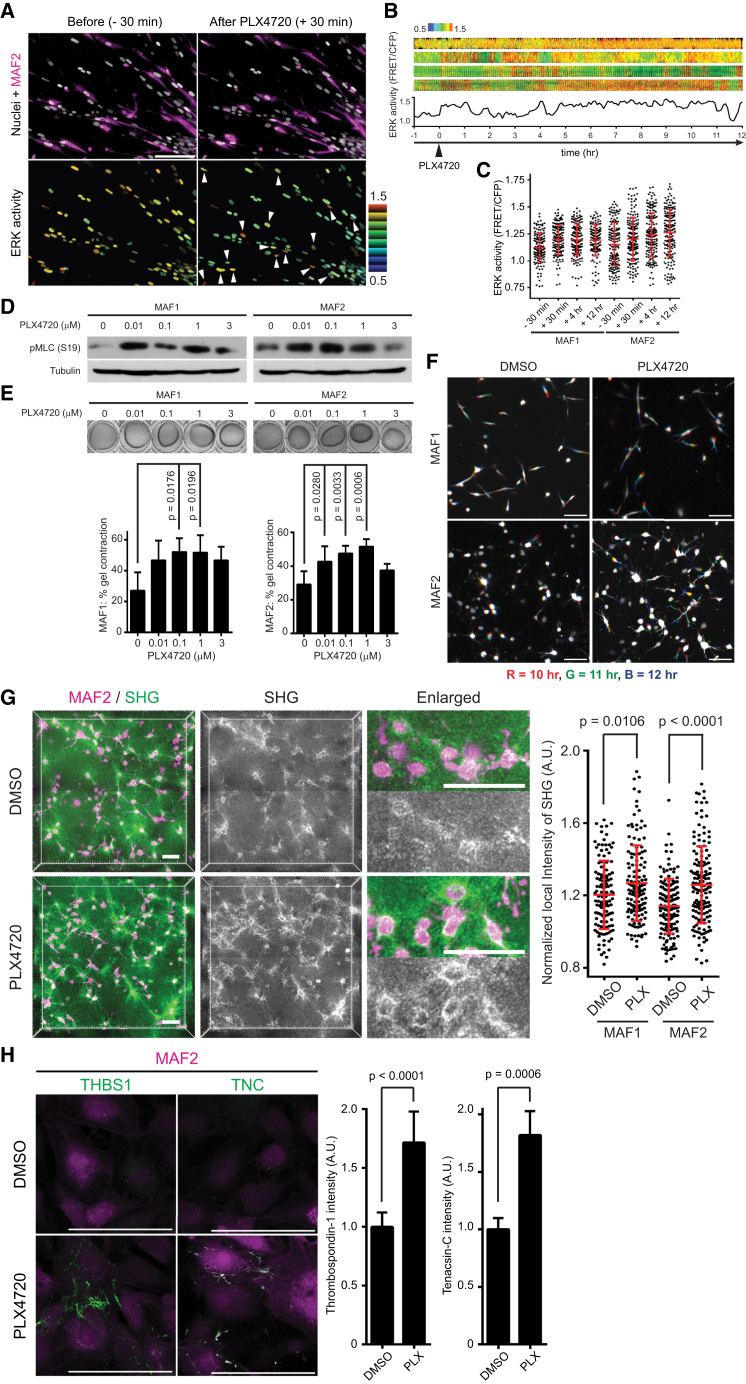

PLX4720 Activates MAFs, Leading to Matrix Remodeling

The data above do not fit with existing models of drug resistance. The adaptation is too quick to be genetic and unlike the relief of negative feedback described, the mechanism that we observe cannot be mediated by melanoma cells alone (Lito et al., 2012). We therefore hypothesized that PLX4720 might be having an effect on the tumor stroma. To test this, we engineered MAFs to contain the EKAREV-NLS biosensor and also express mCherry to enable them to be distinguished from melanoma cells. Spheroid co-cultures of 5555 and MAFs were imaged before and during the response to PLX4720. Strikingly, EKAREV FRET signal increased in MAF shortly after the addition of PLX4720 (Figures 3A–3C and S3A and Movie S2). As expected, EKAREV signal in the melanoma cells decreased immediately after the addition of the drug. ERK activation in MAFs by PLX4720 was confirmed by western blotting (Figure S3B). PLX4720 also slightly increased MAF proliferation (Figure S3C). We next tested whether PLX4720 might modulate the function of MAFs. A key feature of fibroblastic stroma is its ability to remodel the extracellular matrix (Kalluri and Zeisberg, 2006). This can be assayed using collagen gel contraction assays and imaging of collagen fibers by second harmonic generation (SHG) (Calvo et al., 2013). PLX4720 enhanced the matrix remodeling capability of both MAF1 and MAF2 and increased phosphorylation of the key regulator of actomyosin contractility, MLC2/MYL9 (Figures 3D and 3E). PLX4720 also induced dynamic protrusions in MAFs (Figure 3F and Movie S3) and promoted the formation of dense collagen fibrils (Figure 3G). In contrast to MAFs, PLX4720 did not promote significant gel contraction by normal fibroblasts (Figure S3D). This indicates that some prior level of activation is likely to be required for PLX4720 to modulate fibroblast function.

Figure 3.

PLX4720 Paradoxically Activates Melanoma-Associated Fibroblasts

(A–C) 5555-EKAREV-NLS and MAF1/2-EKAREV-NLS-mCherry co-cultured spheroids were embedded in collagen gels and treated with PLX4720 (1 μM) at time = 0. Upper images in (A) indicate 5555 and MAF2 nuclei (gray) and MAF2 (magenta), and lower images indicate ERK activity (FRET/CFP) in 5555 and MAF2 (pointed by arrowheads) before (−30 min) and after (+30 min) treatment. Kymographs of ERK activity in five representative MAF2 cells are shown in (B), and ERK activities at time −30 min, +30 min, +4 hr, and +12 hr are quantified and shown in (C) as scatterplots with mean ± SD. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

(D) Immunoblotting for indicated proteins in MAF1/2 treated with different concentrations of PLX4720 (0–3 μM).

(E) Representative images and quantification of gel contraction by MAF1/2 treated with different concentrations of PLX4720 (0–3 μM). Histograms show quantification of three independent experiments (mean ± SD).

(F) Motion analysis of MAF1/2 in the gel contraction assay treated with 0.1% DMSO or PLX4720 (1 μM), in which three different time points are shown overlain in red (10 hr), green (11 hr), and blue (12 hr). Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(G) Representative images of MAF2 and second harmonic generation (SHG) in the gel contraction assay. Local SHG intensities around MAFs were calculated and quantified by normalizing to the background signals. Each dot indicates SHG signal from a single MAF, and bars indicate mean ± SD. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(H) Immunostaining of non- permeabilized MAF2 (in magenta) with anit-thrombospondin-1 (THBS1) and anti-tenascin-C (TNC) antibodies, treated with DMSO (0.1%) or PLX4720 (1 μM) for 24 hr. Relative fluorescence intensity of THBS1 and TNC are quantified and shown (mean ± SD).

Scale bars represent 100 μm. See also Figure S3 and Movies S2 and S3.

To obtain a global perspective on how PLX4720 affects MAFs, we performed microarray analysis. This revealed coordinated upregulation of the expression of many extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules in PLX4720-treated MAFs (Figures S3E and S3F; Table S1). The upregulation of thrombospondin-1 (THBS1) and tenascin-C (TNC) were confirmed using quantitative immunofluorescence (Figure 3H). In contrast, the expression of soluble growth factors previously implicated in resistance to BRAF inhibitors was largely unchanged (Figure S3E).

Interestingly, we noticed that PLX4720 increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) α in MAFs (Figure S3E), and previous work has shown that stromal fibroblasts are dependent on PDGFR signaling (Erez et al., 2010; Kalluri and Zeisberg, 2006; Pietras et al., 2008). We hypothesized that PLX4720 might activate MAFs by enhancing the activity of PDGFRα- and Ras-dependent signaling through the “paradoxical” activation of CRAF (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010; Heidorn et al., 2010; Nazarian et al., 2010; Poulikakos et al., 2010; Villanueva et al., 2010). Therefore, we investigated the effect of inhibiting PDGFR on both basal and PLX-induced matrix remodeling by MAFs. Figure S3G shows that both basal and PLX4720-induced MAF activity were greatly reduced by imatinib and sunitinib, two kinase inhibitors that target PDGFR in common. These experiments demonstrate that PLX4720 enhances RTK-dependent functions of MAFs.

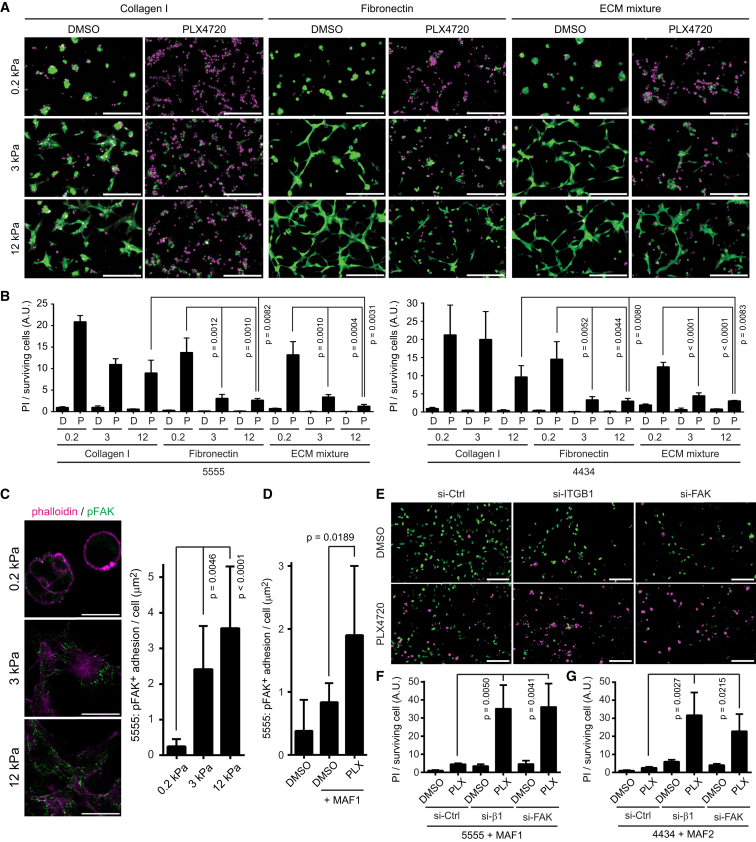

ECM Composition and Stiffness Cooperate to Provide Tolerance to PLX4720

The data above show that PLX4720 elicits changes in matrix production and remodeling by MAFs. To test if the ECM was sufficient to modulate the response of melanoma cells to PLX4720, we varied both matrix composition and matrix stiffness. Figure S4A shows that fibronectin (FN) consistently reduces the effect of PLX4720 on both 5555 and 4434 melanoma cells. Other matrix components, including THBS1/2 and TNC, have more variable effects between the two cell lines. In addition to matrix composition, matrix stiffness affects the behavior of cancer cells. Therefore, we combined variations in matrix composition and matrix stiffness. Polyacrylamide gels ranging from 0.2 kPa (similar to adipose tissue) to 12 kPa (similar to stiff tumors or muscle) were coated with either collagen I, FN, or a combination of FN, THBS1/2, and TNC. Melanoma cells on low stiffness collagen I showed high levels of cell death following BRAF inhibition (Figures 4A and 4B). However, this was greatly abrogated if cells were cultured on FN matrices with either 3 kPa or 12 kPa stiffness, with the most impressive cell survival on 12 kPa FN-, THBS1/2-, and TNC,containing matrices (Figures 4A and 4B). These data demonstrate that an appropriate matrix composition and stiffness can render BRAF-mutant melanoma cells insensitive to PLX4720.

Figure 4.

ECMs and Rigid Substrates Mediate Drug Tolerance through Integrin β1-FAK Activation

(A and B) 5555-mEGFP (in green) were seeded on polyacrylamide / bis-acrylamide gels with different stiffness (0.2, 3 and 12 kPa) coated with the indicated ECMs (ECM mixture contains FN, TNC, THBS1, and THBS2). Twenty-four hours after treatment with DMSO (0.1%) or PLX4720 (1 μM), cells are stained with propidium iodide (PI, in magenta). PI signals from the same experiments with 5555/4434-YFP-NLS were quantified in (B) (mean ± SD). Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(C) 5555 cells cultured on the fibronectin-coated gels with the indicated stiffness were stained with a phospho-FAK antibody. The area of pFAK positive adhesion is quantified (mean ± SD). Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(D) 5555 cells co-cultured with or without MAF1 on collagen gels were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or PLX4720 (1 μM) for 24 hr and stained with a phospho-FAK antibody. The area of pFAK positive adhesion in 5555 cell is quantified and shown as mean ± SD.

(E) 5555-YFP-NLS (in green) transfected with the indicated siRNAs were co-cultured with MAF1 overnight. Then, cells were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or PLX4720 (1 μM) for 24 hr, followed by PI staining (in magenta). Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(F) PI signals of (E) were quantified and shown as mean ± SD (G) PI signals from same experiments as in (E) using 4434 + MAF2 co-cultures were quantified and shown as mean ± SD.

See also Figure S4.

Integrin β1 and FAK Signaling Leads to ERK Re-activation in Melanoma Cells

Increasing the stiffness of fibronectin matrices lead to the re-organization of integrin β1 into focal adhesions and elevated pFAK levels (Figures 4C and S4B). Furthermore, treatment of co-cultures with PLX4720 led to the relocation of active integrin β1 into fibrillar adhesions and increased pFAK signals (Figures 4D and S4C). To determine if the changes in integrin organization and FAK signaling are relevant for the adaptation of melanoma-MAF co-cultures to PLX4720, we investigated the effect of combined PLX4720 treatment and experimental perturbation of integrin β1 and FAK. Combination of PLX4720 with either integrin β1 or FAK depletion led to prevention of ERK/MAPK re-activation and synergistic induction of cell death (Figures 4E–4G, S4D, and S4E).

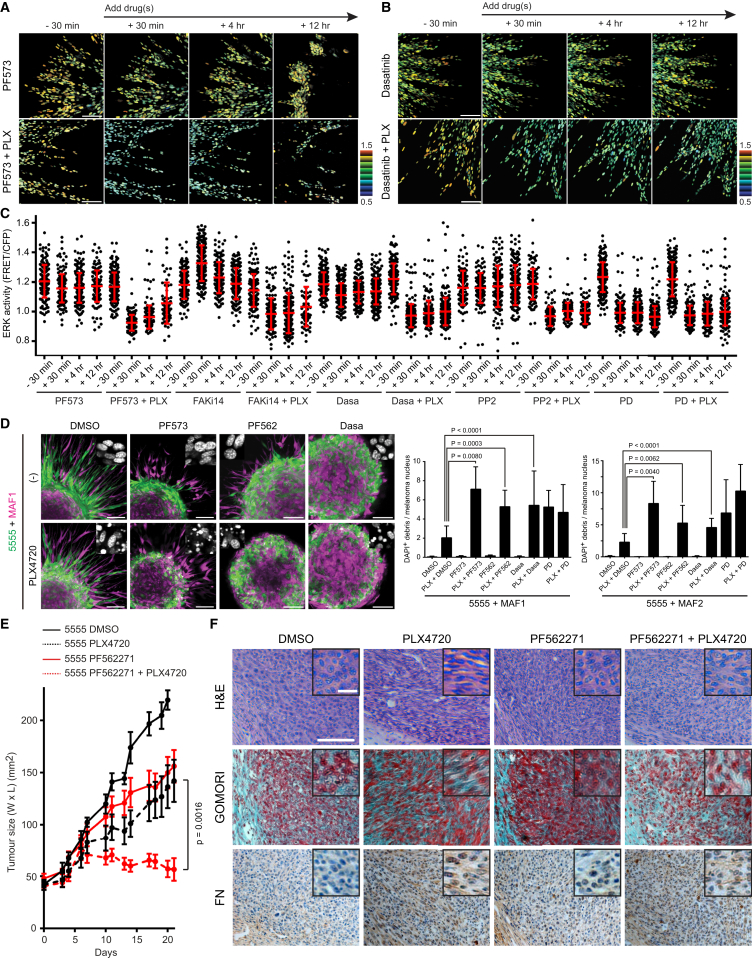

We next investigated whether combining BRAF inhibition with pharmacological targeting of signaling downstream of integrin β1 would be effective. Multiple FAK inhibitors (PF573228, PF562271, FAKi14) prevented the re-activation of ERK/MAPK signaling in melanoma/MAF co-cultured spheroids treated with PLX4720 (Figures 5A, 5C, S5A, and S5B and Movie S4, see also Figure 2E; all quantification is collated in Figure S5G, and similar results with 4434 cells in Figures S5H and S5I). Treatment of PLX4720-naive cells with FAK inhibitors alone did not lead to reduced ERK activity (Figures 5A, 5C, S5A, and S5B). As expected, combined BRAF and MEK inhibition lead to a stable reduction in ERK activity (Figures 5C and S5C).

Figure 5.

Simultaneous Inhibition of BRAF and FAK Effectively Induces Cell Death in 5555 Cells

(A–C) 5555-EKAREV-NLS and MAF1-mCherry co-cultured spheroids were embedded in collagen gels and treated with indicated drugs: PF573228 (1 μM), FAK inhibitor 14 (1 μM), dasatinib (200 nM), PP2 (1 μM) ± PLX4720 (1 μM). ERK activities at time −30 min, +30 min, +4 hr, and +12 hr are quantified and shown in (C) as scatterplots with mean ± SD. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(D) 5555-mEGFP (green) and MAF1/2-mCherry (magenta) co-cultured spheroids were embedded into collagen gels and treated with 0.1% DMSO, PF573228 (1 μM), PF562271 (1 μM), dasatinib (200 nM) ± PLX4720 (1 μM) for 48 hr. Representative DAPI-staining images are also shown in each image, and the ratio of DAPI-positive debris and melanoma nucleus was calculated and shown as mean ± SD. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(E and F) 5555 cells were subcutaneously allografted in C57BL/6 mice and treated with DMSO (4%), PLX4720 (25 mg/kg), PF562271 (50 mg/kg), or the combination. Tumor growth in each group is shown in (E) (mean ± SD, nine mice in control group and ten in other groups), and representative images of H&E, Gomori trichrome (collagen fibers in bright blue), and anti-fibronectin staining are shown in (F).

Enlarged view is also shown as an inset on each image. Scale bars represent 100 μm (low magnification) and 20 μm (high magnification). See also Figure S5 and Movie S4.

In accordance with the results of EKAREV FRET imaging, combination of PLX4720 with FAK inhibition led to synergistic induction of cell death in the co-cultured spheroids (Figure 5D). These combinations were equally as effective as PLX4720 combined with PD184352. Because FAK activity is often linked to Src function, we tested the effect of two Src inhibitors in combination with PLX4720. Both dasatinib and PP2 effectively prevented the re-activation of ERK signaling following PLX4720 treatment (Figures 5B, 5C, and S5D and Movie S4). Furthermore, the combination of PLX4720 and dasatinib led to significantly increased melanoma cell death (Figure 5D). Neither FAK nor Src inhibition reduced the viability of melanoma mono-cultures (Figure S5J). These data demonstrate the critical role of adhesion-mediated signaling via integrin β1, FAK, and Src in the adaptive re-activation of ERK/MAPK following BRAF inhibition in tumor/stroma co-cultures.

Both basal and PLX4720-enhanced MAF activity can be reduced by targeting PDGFR (Figure S3G). This predicts that PDGFR inhibition should also synergize with PLX4720 to reduce ERK activity. We tested this by monitor EKAREV signals following the combination of PLX4720 and imatinib (autofluorescence of sunitinib prevented us from testing its effect in this assay). This combination reduced the re-activation of ERK, while imatinib alone had no effect (Figures S5E and S5F). These data support our hypothesis that PDGFR signaling in the stroma contributes to ERK re-activation in melanoma cells.

We next tested whether BRAF and FAK inhibition would synergize to control melanoma growth in vivo. 5555 melanoma tumors were allowed to reach 4–8 mm before mice began receiving daily doses of PLX4720, PF562271, PLX4720 and PF562271, or vehicle. Figure 5E shows that only the combination of BRAF and FAK inhibitors led to effective control of tumor size; either inhibitor alone had only a modest effect. PLX4720-treated tumors had increased aligned fibrous ECM and FN, and this was associated with FAK-dependent elongation of melanoma cells (Figure 5F). These data indicate that combined BRAF and FAK inhibition is a promising strategy for improving management of BRAF mutant melanoma.

Stromal Support for Residual Disease in Models Exhibiting Incomplete Responses to PLX4720

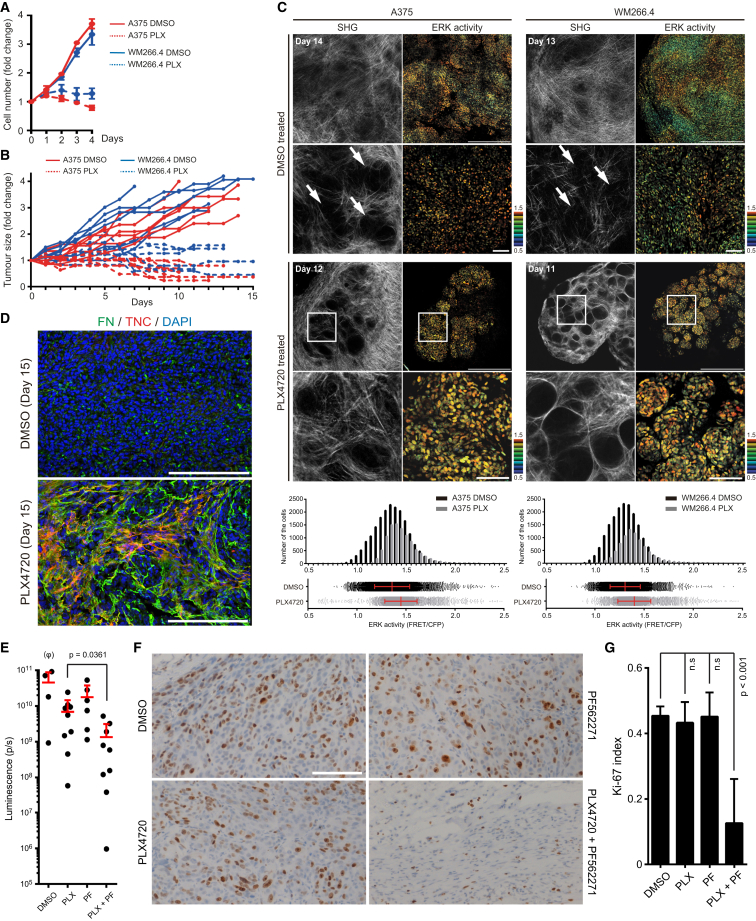

The data described above demonstrate that MAFs provide a mechanism for mouse BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines refractory to PLX4720 in vivo. However, the majority of human BRAF-mutant melanoma respond well to BRAF inhibition before the emergence of resistant disease over many months (Chapman et al., 2011). We were interested whether our findings regarding the role of the stroma in providing drug tolerance were relevant to the survival of melanoma cells in between the initial administration of BRAF inhibitors and the ultimate emergence of genetically resistant cells. Therefore, we examined ERK/MAPK activity and stromal changes in two models of human melanoma that exhibit a clear response to BRAF inhibition in vivo. Figures 6A and 6B show that A375 and WM266.4 human melanoma cells are sensitive to PLX4720 both in vitro and in vivo. However, tumors did not disappear and typically 2–4 mm of residual disease remained during PLX4720 treatment. We hypothesized that this residual disease may be supported by signals from the stroma. Intravital imaging of the EKAREV biosensor revealed that the residual disease after 11–14 days of PLX4720 treatment exhibited similar levels of ERK/MAPK signaling to the pre-treatment tumors (Figures 6C and S6A). Based on our analysis of 5555 and 4434 models, we predict the following: there should be changes in the stroma of PLX4720-treated A375 and WM266.4 tumors, the melanoma cells should not be intrinsically resistant to PLX4720 at this stage, but that they should use FAK- and Src-dependent signaling to sustain ERK/MAPK activity and survival. Both A375 and WM266.4 exhibited clear changes in collagen SHG when treated with PLX4720 (Figure 6C). This is consistent with increased matrix deposition and remodeling by fibroblasts. Immunohistochemical staining, and Gomori’s trichrome staining confirmed that the residual disease was rich in fibroblastic stroma and had higher levels of fibrillar collagen, FN and TNC (Figures 6D and S6A). Furthermore, conformation specific antibodies revealed increased active integrin β1 levels in PLX-treated tumors (Figure S6B).

Figure 6.

Stromal Cells Provide Safe Haven to Tolerate BRAF Inhibition for Drug-Sensitive Human Melanoma Cells

(A and B) Growth curves of the indicated melanoma cells in vitro (A) (mean ± SD) and in vivo (B) treated with DMSO (0.1% in vitro and 4% in vivo) or PLX4720 (1 μM in vitro and 25 mg/kg in vivo).

(C) Intravital images of A375- and WM266.4-expressing EKAREV-NLS in nude mice. Images are from mice treated with DMSO (4%) or PLX4720 (25 mg/kg) for the indicated days. Arrows in high magnification images of DMSO-treated tumors indicate small cages created by thick collagen fibers (detected by second harmonic generation: SHG). In PLX4720-treated tumors, the regions in white squares are magnified and shown below. Distribution (scatterplots with mean ± SD) and histogram of ERK activities in A375 and WM266.4 tumors are shown at the bottom. Scale bars represent 500 μm (low magnification) and 100 μm (high magnification).

(D) Frozen sections of WM266.4 tumors treated with DMSO or PLX4720 for 15 days were double-stained with anti-fibronectin (in green) and anti-tenascin-C (in red) antibodies. Scale bars represent 200 μm.

(E) A375 cells stably expressing firefly luciferase grown subcutaneously in nude mice were treated with DMSO (4%), PLX4720 (25 mg/kg), PF562271 (50 mg/kg), or the combination. Bioluminescence from the tumors was analyzed at day 25 and shown (mean ± SD). (φ) Please note that DMSO group (n = 4) contains fewer mice than other groups because the higher growth rates of these tumors meant that some mice were killed before day 25.

(F) A375 tumors treated with the indicated drug(s) for 29 days were stained with an anti-Ki-67 antibody. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

(G) Ki-67 index was measured from three different positions in six different tumors treated with the indicated drugs for 18–29 days.

Data are represented as mean ± SD. Please note that necrotic areas with myeloid cell infiltration in PLX4720 + PF562271 tumors were excluded from the analysis. See also Figure S6.

To formally confirm that the melanoma cells were dependent on extrinsic signals for their tolerance of PLX4720, we re-isolated A375 and WM266.4 cells from the residual disease that persisted following PLX4720 treatment. Figure S6C shows that these cells are just as sensitive to PLX4720 as parental cells when cultured in isolation without a supportive tumor microenvironment. These data demonstrate the persistence of residual disease is due to cell extrinsic factors that re-activate ERK signaling by a BRAF-independent mechanism. To further test our hypothesis, we investigated whether the ERK signaling in residual disease was dependent on FAK and Src function. Combination of either PF573228 or dasatinib with PLX4720 led to more prolonged ERK inhibition in tumor explants (Figure S6D). Finally, we tested whether combining BRAF and FAK inhibition would have a synergistic effect on A375 tumor burden. Established A375 tumors (5–7 mm) were treated with PLX4720, PF562271, PLX4720, and PF562271, or vehicle for up to 30 days. We observed that combined BRAF and FAK inhibition led to significantly reduced burden compared to either treatment alone (Figure 6E); indeed, no biolumiscence signal could be detected in one mouse. Co-targeting BRAF and FAK also triggered extensive neutrophil and macrophage infiltration (Figure S6E). More surprisingly, although PLX4720 controls total melanoma volume in this tumor model, it has a minimal effect on Ki-67 positivity, whereas PLX4720 + PF562271 leads to a clear reduction in Ki-67 positive melanoma cells (Figures 6F and 6G). These data suggest that PLX4720-treated tumors continue to proliferate, albeit balanced by cell death. This would enable the evolution of resistant clones even in a PLX4720-treated tumor that is not increasing in size.

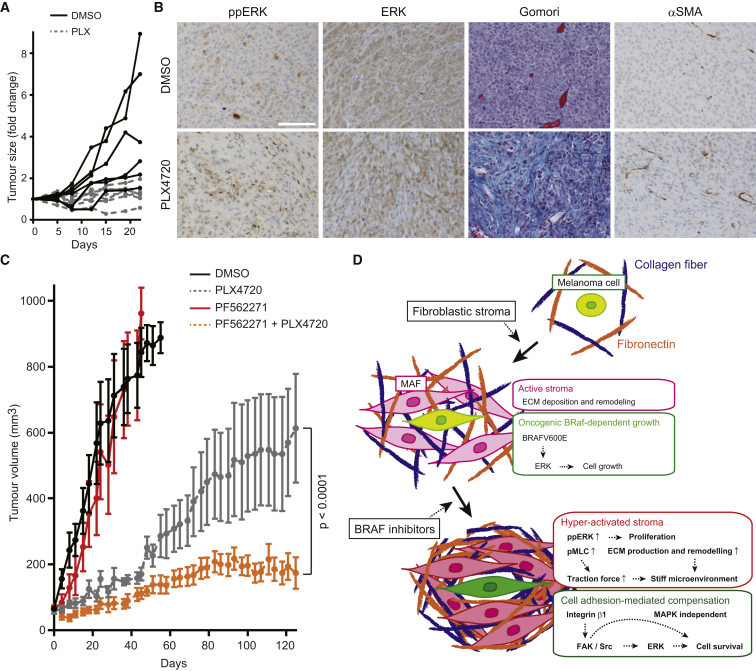

We next investigated changes in the tumor stroma and the effect of FAK inhibition in a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model. A PDX was established from a vemurafenib naive BRAF mutant melanoma. Figure 7A shows that this grows well in control NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice, but the growth of this PDX was controlled by PLX4720, although significant disease remained. In agreement with our analyses of A375 and WM266.4 tumors, histological analysis of the residual disease in PLX4720-treated mice revealed increased fibrous ECM, higher numbers of αSMA-positive cells, and active ERK/MAPK signaling (Figure 7B). We next explored whether this PDX model would eventually fail PLX4720 therapy, and whether FAK inhibition might reduce this failure. After roughly 50 days of PLX4720 treatment, the PDX tumors began to grow, indicating therapy failure (Figure 7C). FAK inhibition alone had no effect on tumor growth, but when combined with PLX4720 lead to significantly increased tumor control both at early time points and, more importantly, after 4 months when PLX4720-treated tumors were failing therapy (Figure 7C). No adverse effects, such as weight loss, were observed in mice treated with PLX4720 and PF562271 for 4 months (Figure S7A).

Figure 7.

Combinatorial Inhibition of BRAF and FAK Suppresses the Growth of Patient-Derived Xenograft

(A) Growth curves of vemurafenib-naive patient derived xenograft (PDX) in IL-2 NSG mice treated with DMSO (5%) or PLX4720 (45 mg/kg) for 22 days.

(B) Anti-phospho-ERK, anti-ERK, Gomori trichrome, and anti-αSMA staining of the fixed PDX samples treated with DMSO or PLX4720 for 22 days. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

(C) Growth curves of PDX treated with DMSO (4%), PLX4720 (45 mg/kg), PF562271 (50 mg/kg), or the combination. Data are represented as mean ± SD, seven mice per group.

(D) Scheme of drug tolerance mechanisms against BRAF selective inhibitors.

See also Figure S7.

Alterations in Tumor Stroma and ECM in Vemurafenib-Treated Patients

The data above demonstrate that BRAF inhibition can directly affect the fibroblastic stroma leading to remodeled ECM and adhesion-dependent signaling to ERK that negates the effect of BRAF inhibition in the melanoma cells. We find histologic features that are compatible with our experimental models in patient samples prior to vemurafenib treatment and following disease progression on vemurafenib (Table S2): these include changes in the stroma and melanoma cell morphology following vemurafenib treatment. Figure S7B shows increased fibrous ECM and αSMA-positive MAFs were visible in Patients 1 and 4 after failure of BRAF inhibition. In Patient 4, there was an increase in elongated melanoma cells. These analyses confirm that BRAF inhibition can modulate the fibrous ECM and fibroblastic stroma in melanoma patients. Taken together with the experimental work, we show how an effect of BRAF inhibition on the stroma generates a drug-tolerant microenvironment that supports residual disease before the emergence of genetic cell intrinsic drug resistance mechanisms (Figure 7D).

Discussion

A common feature of kinase-targeted therapies is a period of response followed by the emergence of resistant disease. In melanoma, different genetic resistance mechanisms can develop in the same patient (Shi et al., 2014; Van Allen et al., 2014), often at multiple metastatic sites (Shi et al., 2014). These data are not easily reconciled with a model of a pre-existing genetically resistant sub-clone; thus, resistant melanoma cells may arise after treatment with vemurafenib has begun. How significant numbers of BRAF-mutant cells survive therapy prior to the emergence of genetic mutations or epigenetic changes that enable resistance is not well understood, and here we describe a mechanism enabling the survival of large numbers of BRAF-mutant melanoma cells following PLX4720 treatment. This mechanism has two key features: first, the fibroblastic stroma is “paradoxically” activated by BRAF inhibition; and second, adhesion-dependent signals from the altered tumor microenvironment lead to BRAF-independent ERK/MAP kinase activity.

BRAF inhibitors can promote Ras-driven signaling through CRAF (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2010; Heidorn et al., 2010; Nazarian et al., 2010; Poulikakos et al., 2010; Villanueva et al., 2010); however, it was not clear if this mechanism may act on Ras-signaling in the stroma and how this may affect therapeutic efficacy. We find that PLX4720 increases ERK/MAPK signaling, elevates matrix production, and increases MLC phosphorylation and matrix remodeling, which is likely due to enhancing RTK-Ras signaling. These compounds probably act through their effects on PDGFR, which is upregulated by PLX4720 and has previously been implicated in the function of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (Erez et al., 2010; Kalluri and Zeisberg, 2006; Pietras et al., 2008). Dabrafenib is likely to activate the fibroblastic stroma in a similar manner to PLX4720 (Gibney and Zager, 2013; Huang et al., 2013). Interestingly, we found that PLX4720 did not enhance the activity of normal fibroblasts; this may be because they do not have elevated RTK signaling.

The ability of MAFs to confer PLX4720 tolerance depends on integrin β1 and FAK in the melanoma cells. Furthermore, fibronectin-rich matrices of the appropriate stiffness are sufficient to abrogate the effects of BRAF inhibition. We propose that certain ECM environments provide “safe havens” for melanoma cells to tolerate BRAF targeted therapy. Although extrinsic signals from the tumor microenvironment can support four different BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines in the presence of PLX4720, the magnitude of this protective effect varied—these models recruit stroma with different composition and different degrees of activation. Therefore, the magnitude of the effect of PLX4720 on the stroma would be variable. Alternatively, melanoma cells may differ in their ability to activate adhesion-dependent FAK and Src to ERK/MAP kinase. Although we find no role for HGF in our analyses, the ability of c-Met to drive Rac activation and elongated modes of cell migration could be a point of commonality with the work of Strausmann et al. (Straussman et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2014). Furthermore, the relief of negative inhibition that can be triggered by BRAF inhibition may also sensitize melanoma cells to integrin/FAK-mediated ERK activation (Lito et al., 2012, 2013).

There are currently moves to use combined blockade of BRAF and MEK to improve outcomes in melanoma (Flaherty et al., 2012; Wagle et al., 2014). Although this approach extends lifespan, it is rarely curative (Larkin et al., 2014). We find that BRAF and FAK inhibition is another promising strategy. Both strategies are similarly effective at inducing melanoma cell death. In the long term, combined BRAF and FAK blockade improves tumor control but rarely eliminates tumors entirely, and some PDX tumors resume very slow growth after 2–3 months. The lack of cure may reflect problems in drug access. Our results also indicate that BRAF and Src inhibition will be effective and recent results using a combined RAF and SRC inhibitor support this (Girotti et al., 2015). Furthermore, because many RTKs require signals from cell adhesions to function (Butcher et al., 2009; Paszek et al., 2005; Sulzmaier et al., 2014), FAK targeting may attenuate divergent signaling from cell adhesion receptors and RTKs to cell survival and proliferation machinery, and this may provide some benefit over simply targeting ERK signaling.

To conclude, multiple mechanisms of cell-intrinsic resistance to melanoma have been documented. In patients, cell-intrinsic resistance to vemurafenib typically emerges over a period of months. The mechanisms that sustain melanoma cells in the period between initial response and disease progression on therapy are unclear. We describe how paradoxical activation of the fibroblastic stroma enables matrix-derived signaling via integrin β1 and FAK to promote ERK activation and cell survival. This could sustain the pool of melanoma cells from which intrinsic resistant clones emerge. We propose that by reducing the numbers of residual melanoma cells, there would less material from which truly resistant cells could arise. This should lead to longer periods of progression-free survival and possibly even cure.

Experimental Procedures

Cells and Probes

BRAF-mutant (5555 and 4434) and NRAS-mutant (C790) mouse melanoma cell lines were established from C57BL/6_BRAF +/LSL-BRAFV600E ; Tyr::CreERT2+/o (Dhomen et al., 2009) and C57BL/6_NRAS +/LSL-NRASG12D ; Tyr::Cre-A (Pedersen et al., 2013), respectively. B16F10 mouse melanoma cell lines, and A375 and WM266.4 human melanoma cell lines were a gift from Prof. Chris Marshall (Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK). Melanoma cells were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum/1% PenStrep (GIBCO). The FRET biosensors for ERK/MAPK (EKAREV-NLS/NES) was described previously (Komatsu et al., 2011) and were introduced into the cells with PiggyBac transposon system (Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UK).

Mouse Allograft/Xenograft Model

Animal experiments were done in accordance with UK regulations under project license PPL/80/2368. For melanoma allograft model, 2 × 106 5555 or 4434 cells were suspended into 200 μl PBS and subcutaneously injected in the flanks of C57BL/6 mice or C57BL/6_ROSA26_mTmG mice. After 10–14 days when the cells form palpable tumors, the mice were dosed daily by oral gavage with vehicle (4% DMSO), PLX4720 (25 mg/kg), PF562271 (50 mg/kg), or the combination. The tumor size was monitored daily by calculating length × width (mm2). For experimental lung metastasis, 2 × 106 5555 cells in 200 μl PBS were injected from the tail vein and, after 4 weeks, the mice were killed and the lung tumors are examined further. For human melanoma xenograft model, 2 × 106 A375 or WM266.4 cells in 200 μl PBS were subcutaneously injected in the flanks of nude mice. After about 2 weeks when palpable tumors formed, we started further experiments. For skin-flap tumor imaging, the mouse was anesthetized and the tumor was surgically exposed and imaged through a coverslip with a Zeiss LSM780 inverted microscope as described elsewhere (Giampieri et al., 2009). For bioluminescence imaging, nude mice bearing A375 tumors stably expressing firefly luciferase were anesthetized, intraperitoneally injected with D-Luciferin (150 mg/kg, PerkinElmer), and imaged under IVIS Spectrum (PerkinElmer).

Patient Samples and Patient-Derived Xenografts

Tumor samples were collected under the Manchester Cancer Research Centre (MCRC) Biobank ethics application no. 07/H1003/161+5 with full informed consent from the patients. The work presented in this manuscript was approved by MCRC Biobank Access Committee application 13_RIMA_01. Metastatic melanoma tumor samples from vemurafenib-resistant patients (nos. 1–5) and from a vemurafenib-naive patient (no. 6) were obtained immediately after surgery. For PDX models, necrotic parts of the tumors were removed and 5 × 5 × 5 mm pieces were implanted subcutaneously in the right flanks of 5- to 6-week-old female IL-2 NSG mice. When the PDXs reached 1500 mm3 volume, they were excised, and viable tissue was dissected into 5 mm cubes and transplanted into additional mice using the same procedure. Genomic and histological analyses had confirmed that the tumors at each point were derived from the starting material. Following transplantation, tumors were allowed to grow to ∼60–80 mm3, and the mice were randomized before initiation of treatment by daily orogastric gavage of PLX4720 (45 mg/kg), PF562271 (50 mg/kg), vehicle (5% DMSO, 95% water), or the combination for the indicated days.

Time-Lapse FRET Imaging of Cultured Melanoma Spheroids

Tumor spheroids cultured in collagen gel on a glass bottom dish/plate were imaged with an LSM780 inverted microscope through 20× objective every 5 min for up to 13 hr. For the dual-emission ratio imaging, the FRET biosensor was excited by a Chameleon Ti:sapphire Laser (Coherent Inc.) at 820 nm excitation wavelength. The emission light was separated by beam splitters into 463–506 nm for CFP and 515–559 nm for FRET. Details in microscopy, data analysis, and image processing are available in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Acknowledgments

We would like to dedicate this study to the memory of Francois Lassailly, who pioneered intravital imaging at our institute and will be much missed. We thank Emma Nye and Tamara Denner for help with immuno-histochemistry, members of the BRU for help with mouse husbandry, members of Intravital Imaging laboratory for technical support with bioluminescence imaging, Dominic Alibhai for help with FLIM imaging, and Ilaria Malanchi and laboratory members for advice and discussions. This work was funded by Cancer Research UK grants A5317, C5759/A12328, Japan Brain Foundation, Uehara Memorial Foundation, the NIHR Royal Marsden Hospital/Institute of Cancer Research Biomedical Research Centre for Cancer, Wellcome Trust grant 100282/Z/12/Z, and the EU Marie-Curie initiative grant 329047. R.G., A.V., and R.M. either are or have been employed by The Institute of Cancer Research are subject to a “Rewards to Inventors Scheme” that may reward contributors to a programme that is subsequently licensed.

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Accession Numbers

The National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus database accession number for the microarray data sets is GSE63160.

Supplemental Information

5555-EKAREV-NLS mono-cultured spheroids (Mono) or co-cultured spheroids with MAF1-mCherry (+ MAF1) were embedded in collagen gels and treated with DMSO (0.1%) or PLX4720 (1 μM). Images were acquired every 5 min for 13 hr. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

5555-EKAREV-NLS and MAF1-EKAREV-NLS-mCherry co-cultured spheroids were embedded in collagen gels and treated with PLX4720 (1 μM). Images were acquired every 5 min for 13 hr. White arrows indicate MAF nuclei to be focused on. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

MAF1/2-mCherry embedded in collagen/Matrigel with 10%FBS were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or PLX4720 (1 μM). Images were acquired every 10 min for 13 hr. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

5555-EKAREV-NLS and MAF1-mCherry co-cultured spheroids were embedded in collagen gels and treated with PF573228 (1 μM) ± PLX4720 (1 μM) or dasatinib (200 nM) ± PLX4720 (1 μM). Images were acquired every 5 min for 13 hr. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

References

- Butcher D.T., Alliston T., Weaver V.M. A tense situation: forcing tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:108–122. doi: 10.1038/nrc2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo F., Ege N., Grande-Garcia A., Hooper S., Jenkins R.P., Chaudhry S.I., Harrington K., Williamson P., Moeendarbary E., Charras G., Sahai E. Mechanotransduction and YAP-dependent matrix remodelling is required for the generation and maintenance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:637–646. doi: 10.1038/ncb2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman P.B., Hauschild A., Robert C., Haanen J.B., Ascierto P., Larkin J., Dummer R., Garbe C., Testori A., Maio M., BRIM-3 Study Group Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhomen N., Reis-Filho J.S., da Rocha Dias S., Hayward R., Savage K., Delmas V., Larue L., Pritchard C., Marais R. Oncogenic Braf induces melanocyte senescence and melanoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker B.J., Talpaz M., Resta D.J., Peng B., Buchdunger E., Ford J.M., Lydon N.B., Kantarjian H., Capdeville R., Ohno-Jones S., Sawyers C.L. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker B.J., Guilhot F., O’Brien S.G., Gathmann I., Kantarjian H., Gattermann N., Deininger M.W., Silver R.T., Goldman J.M., Stone R.M., IRIS Investigators Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:2408–2417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erez N., Truitt M., Olson P., Arron S.T., Hanahan D. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are activated in incipient neoplasia to orchestrate tumor-promoting inflammation in an NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty K.T., Puzanov I., Kim K.B., Ribas A., McArthur G.A., Sosman J.A., O’Dwyer P.J., Lee R.J., Grippo J.F., Nolop K., Chapman P.B. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:809–819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty K.T., Infante J.R., Daud A., Gonzalez R., Kefford R.F., Sosman J., Hamid O., Schuchter L., Cebon J., Ibrahim N. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1694–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giampieri S., Manning C., Hooper S., Jones L., Hill C.S., Sahai E. Localized and reversible TGFbeta signalling switches breast cancer cells from cohesive to single cell motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1287–1296. doi: 10.1038/ncb1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibney G.T., Zager J.S. Clinical development of dabrafenib in BRAF mutant melanoma and other malignancies. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2013;9:893–899. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.794220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girotti M.R., Lopes F., Preece N., Niculescu-Duvaz D., Zambon A., Davies L., Whittaker S., Saturno G., Viros A., Pedersen M. Paradox-breaking RAF inhibitors that also target SRC are effective in drug-resistant BRAF mutant melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey C.D., Ehrhardt A.G., Cellurale C., Zhong H., Yasuda R., Davis R.J., Svoboda K. A genetically encoded fluorescent sensor of ERK activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19264–19269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804598105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzivassiliou G., Song K., Yen I., Brandhuber B.J., Anderson D.J., Alvarado R., Ludlam M.J., Stokoe D., Gloor S.L., Vigers G. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature. 2010;464:431–435. doi: 10.1038/nature08833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidorn S.J., Milagre C., Whittaker S., Nourry A., Niculescu-Duvas I., Dhomen N., Hussain J., Reis-Filho J.S., Springer C.J., Pritchard C., Marais R. Kinase-dead BRAF and oncogenic RAS cooperate to drive tumor progression through CRAF. Cell. 2010;140:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T., Karsy M., Zhuge J., Zhong M., Liu D. B-Raf and the inhibitors: from bench to bedside. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inukai M., Toyooka S., Ito S., Asano H., Ichihara S., Soh J., Suehisa H., Ouchida M., Aoe K., Aoe M. Presence of epidermal growth factor receptor gene T790M mutation as a minor clone in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7854–7858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen A., Beerling E., Medema R., van Rheenen J. Intravital FRET imaging of tumor cell viability and mitosis during chemotherapy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R., Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S., Boggon T.J., Dayaram T., Jänne P.A., Kocher O., Meyerson M., Johnson B.E., Eck M.J., Tenen D.G., Halmos B. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu N., Aoki K., Yamada M., Yukinaga H., Fujita Y., Kamioka Y., Matsuda M. Development of an optimized backbone of FRET biosensors for kinases and GTPases. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:4647–4656. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-01-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin J., Ascierto P.A., Dréno B., Atkinson V., Liszkay G., Maio M., Mandalà M., Demidov L., Stroyakovskiy D., Thomas L. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1867–1876. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lito P., Pratilas C.A., Joseph E.W., Tadi M., Halilovic E., Zubrowski M., Huang A., Wong W.L., Callahan M.K., Merghoub T. Relief of profound feedback inhibition of mitogenic signaling by RAF inhibitors attenuates their activity in BRAFV600E melanomas. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:668–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lito P., Rosen N., Solit D.B. Tumor adaptation and resistance to RAF inhibitors. Nat. Med. 2013;19:1401–1409. doi: 10.1038/nm.3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maemondo M., Inoue A., Kobayashi K., Sugawara S., Oizumi S., Isobe H., Gemma A., Harada M., Yoshizawa H., Kinoshita I., North-East Japan Study Group Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheswaran S., Sequist L.V., Nagrath S., Ulkus L., Brannigan B., Collura C.V., Inserra E., Diederichs S., Iafrate A.J., Bell D.W. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:366–377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok T.S., Wu Y.L., Thongprasert S., Yang C.H., Chu D.T., Saijo N., Sunpaweravong P., Han B., Margono B., Ichinose Y. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar M.D., Tasic B., Miyamichi K., Li L., Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarian R., Shi H., Wang Q., Kong X., Koya R.C., Lee H., Chen Z., Lee M.K., Attar N., Sazegar H. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszek M.J., Zahir N., Johnson K.R., Lakins J.N., Rozenberg G.I., Gefen A., Reinhart-King C.A., Margulies S.S., Dembo M., Boettiger D. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen M., Kusters-Vandevelde H.V., Viros A., Groenen P.J., Sanchez-Laorden B., Gilhuis J.H., van Engen-van Grunsven I.A., Renier W., Schieving J., Niculescu-Duvaz I. Primary melanoma of the CNS in children is driven by congenital expression of oncogenic NRAS in melanocytes. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:458–469. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietras K., Pahler J., Bergers G., Hanahan D. Functions of paracrine PDGF signaling in the proangiogenic tumor stroma revealed by pharmacological targeting. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos P.I., Rosen N. Mutant BRAF melanomas—dependence and resistance. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos P.I., Zhang C., Bollag G., Shokat K.M., Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464:427–430. doi: 10.1038/nature08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos P.I., Persaud Y., Janakiraman M., Kong X., Ng C., Moriceau G., Shi H., Atefi M., Titz B., Gabay M.T. RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E) Nature. 2011;480:387–390. doi: 10.1038/nature10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell R., Molina M.A., Costa C., Simonetti S., Gimenez-Capitan A., Bertran-Alamillo J., Mayo C., Moran T., Mendez P., Cardenal F. Pretreatment EGFR T790M mutation and BRCA1 mRNA expression in erlotinib-treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients with EGFR mutations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:1160–1168. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawver L.K., Slamon D., Ullrich A. Smart drugs: tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:117–123. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Hugo W., Kong X., Hong A., Koya R.C., Moriceau G., Chodon T., Guo R., Johnson D.B., Dahlman K.B. Acquired resistance and clonal evolution in melanoma during BRAF inhibitor therapy. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:80–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordella R., Bell D.W., Haber D.A., Settleman J. Gefitinib-sensitizing EGFR mutations in lung cancer activate anti-apoptotic pathways. Science. 2004;305:1163–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.1101637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosman J.A., Kim K.B., Schuchter L., Gonzalez R., Pavlick A.C., Weber J.S., McArthur G.A., Hutson T.E., Moschos S.J., Flaherty K.T. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:707–714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straussman R., Morikawa T., Shee K., Barzily-Rokni M., Qian Z.R., Du J., Davis A., Mongare M.M., Gould J., Frederick D.T. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–504. doi: 10.1038/nature11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzmaier F.J., Jean C., Schlaepfer D.D. FAK in cancer: mechanistic findings and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:598–610. doi: 10.1038/nrc3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turke A.B., Zejnullahu K., Wu Y.L., Song Y., Dias-Santagata D., Lifshits E., Toschi L., Rogers A., Mok T., Sequist L. Preexistence and clonal selection of MET amplification in EGFR mutant NSCLC. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Allen E.M., Wagle N., Sucker A., Treacy D.J., Johannessen C.M., Goetz E.M., Place C.S., Taylor-Weiner A., Whittaker S., Kryukov G.V., Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group of Germany (DeCOG) The genetic landscape of clinical resistance to RAF inhibition in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:94–109. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva J., Vultur A., Lee J.T., Somasundaram R., Fukunaga-Kalabis M., Cipolla A.K., Wubbenhorst B., Xu X., Gimotty P.A., Kee D. Acquired resistance to BRAF inhibitors mediated by a RAF kinase switch in melanoma can be overcome by cotargeting MEK and IGF-1R/PI3K. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva J., Vultur A., Herlyn M. Resistance to BRAF inhibitors: unraveling mechanisms and future treatment options. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7137–7140. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagle N., Van Allen E.M., Treacy D.J., Frederick D.T., Cooper Z.A., Taylor-Weiner A., Rosenberg M., Goetz E.M., Sullivan R.J., Farlow D.N. MAP kinase pathway alterations in BRAF-mutant melanoma patients with acquired resistance to combined RAF/MEK inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:61–68. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson I.R., Li L., Cabeceiras P.K., Mahdavi M., Gutschner T., Genovese G., Wang G., Fang Z., Tepper J.M., Stemke-Hale K. The RAC1 P29S hotspot mutation in melanoma confers resistance to pharmacological inhibition of RAF. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4845–4852. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1232-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T.R., Fridlyand J., Yan Y., Penuel E., Burton L., Chan E., Peng J., Lin E., Wang Y., Sosman J. Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors. Nature. 2012;487:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

5555-EKAREV-NLS mono-cultured spheroids (Mono) or co-cultured spheroids with MAF1-mCherry (+ MAF1) were embedded in collagen gels and treated with DMSO (0.1%) or PLX4720 (1 μM). Images were acquired every 5 min for 13 hr. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

5555-EKAREV-NLS and MAF1-EKAREV-NLS-mCherry co-cultured spheroids were embedded in collagen gels and treated with PLX4720 (1 μM). Images were acquired every 5 min for 13 hr. White arrows indicate MAF nuclei to be focused on. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

MAF1/2-mCherry embedded in collagen/Matrigel with 10%FBS were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or PLX4720 (1 μM). Images were acquired every 10 min for 13 hr. Scale bars represent 100 μm.

5555-EKAREV-NLS and MAF1-mCherry co-cultured spheroids were embedded in collagen gels and treated with PF573228 (1 μM) ± PLX4720 (1 μM) or dasatinib (200 nM) ± PLX4720 (1 μM). Images were acquired every 5 min for 13 hr. Scale bars represent 100 μm.