Abstract

Human saliva plays a pivotal role in digesting food and maintaining oral hygiene. The presence of electrolytes, mucus, glycoproteins, enzymes, antibacterial compounds, and gingival crevicular fluid in saliva ensures the optimum condition of oral cavity and general health condition. Saliva collection has been proven non-invasive, convenient, and inexpensive compared to conventional venipuncture procedure. These distinctive advantages provide a promising potential of saliva as a diagnostic fluid. Through comprehensive analysis, an array of salivary proteins and peptides may be beneficial as biomarkers in oral and systemic diseases. In this review, we discuss the utility of human salivary proteomes and tabulate the recent salivary biomarkers found in subjects with acute myocardial infarction as well as respective methods employed. In a clinical setting, since acute myocardial infarction contributes to large cases of mortality worldwide, an early intervention using these biomarkers will provide an effective solution to reduce global heart attack incidence particularly among its high-risk group of type-2 diabetes mellitus patients. The utility of salivary biomarkers will make the prediction of this cardiac event possible due to its reliability hence improve the quality of life of the patients. Current challenges in saliva collection are also addressed to improve the quality of saliva samples and produce robust biomarkers for future use in clinical applications.

Keywords: saliva, biomarker, acute myocardial infarction, proteomics, type-2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Human saliva is a biological fluid with myriad of biological functions important for the maintenance of oral and general health. It is a plasma ultra-filtrate containing proteins either synthesized in situ from blood or in the salivary glands 1. Major salivary glands consisting of submandibular glands, sublingual glands, and parotid glands lie at the vicinity of the oral cavity whereas other minor exocrine glands lie beneath the oral mucosa 2. Several roles of saliva in the oral cavity include lubrication and binding, solubilisation of dry food, oral hygiene, and initiation of starch digestion 3. Apart from water as its major constituent, whole saliva also contains bacterial and exfoliated cells, electrolytes, glycoproteins, enzymes, and antibacterial compounds. Likewise, minute amounts of gingival crevicular fluid coexist with saliva in the gingival crevice surrounding the teeth 4.

Changes in saliva quality and quantity are indicative of the wellness of the patient 5. Human saliva, as a mirror of oral and systemic health, provides valuable information because it contains biomarkers specific for the unique physiologic aspects of periodontal and systemic diseases. Proteomic markers from immunoglobulins to bone remodelling proteins were previously discovered in existing periodontal diseases 6. In one study, salivary epidermal growth factor was found to be significantly raised in women with active and nonactive breast cancer compared to healthy women 7. Compared to blood, saliva has been clinically shown to produce more accurate, inexpensive, and convenient results. The diagnostic potential of this fluid has been studied in many laboratories in order to find its advantages over other biological fluids and potential biomarkers in numerous diseases. Unlike plasma, saliva can be readily used for tests since it will not clot. Its noninvasive approach renders this biological fluid an effective alternative to blood and urine testing in monitoring patient's health condition 8.

Whole saliva can be easily collected by drooling, spitting, or swabbing into a designated tube as opposed to invasive blood collection procedure. These methods of obtaining saliva pose minimal risk of contracting deadly pathogens to the healthcare professionals. Plus, sufficient quantities of saliva can be easily obtained for analysis by a practitioner even with modest training. For diagnostic and research purposes, saliva collection kits have been commercially marketed worldwide including Oragene.DISCOVER from DNA Genotek Inc., UltraSal-2™ from Oasis Diagnostics, OraSure® Oral Specimen Collection Device from OraSure Technologies, Inc., Certus® Collection Device from Alere™, and Saliva Collection System from Greiner Bio-One. In one study, budget estimates for both blood and saliva collections were developed by a group of scientists incorporating personnel expenses and corresponding collection methods into the calculation. When comparing both budget estimates, saliva collection was proven to be 48% less costly than blood collection 9. These advantages have attracted many researchers to study and identify potential salivary biomarkers with unparalleled opportunities for clinical applications.

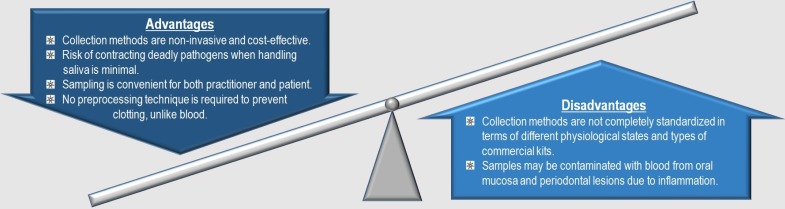

As illustrated in Figure 1, human salivary proteomes exhibit promising potential as biomarkers to predict the onset of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), or heart attack. On a global scale, the disease remains the primary cause of morbidity and mortality. This pathologic event occurs as a result of acute myocardial ischemia when there is evidence of myocardial necrosis 10. According to World Health Organization 11, this disease is one of the major forms of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in which its prevalence constitutes approximately 48% of all deaths in 2008, affecting more than 17 million patients around the globe. Other AMI complications may include severe cardiac disability upon survival of the onset 12.

Figure 1.

Summary of the advantages and disadvantages of saliva as a diagnostic fluid in relation to AMI.

Since AMI is the leading cause of death worldwide, this disease has been selected among other systemic diseases in this review. Recent salivary findings and progress pertaining to this condition will be discussed to elucidate the promising use of saliva as a diagnostic fluid in acute cardiac care among a very high-risk group of type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), as well as relevant methods employed. Current challenges in saliva collection will be highlighted for further improvement on the quality of salivary biomarkers discovered in future.

Human salivary proteomes as biomarkers

Biomarkers can be indicative of a specific physiological or pathological state of a biological fluid including blood and saliva 13. Many researchers worldwide have been studying the use of biomarkers due to its ability to monitor susceptibility, progression, and resolution of diseases, health condition, and treatment outcome. Despite the variability of the term “biomarker” used in diverse aspects of its applications, the most comprehensible definition of biomarker is “cellular, biochemical, molecular, or genetic alterations by which a normal, abnormal, or simple biological process can be recognized or monitored” 14. Any molecular species which demonstrates significant variation in concentration, as compared to those of control subjects, is a potential biomarker. Therefore, if expression of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist is significantly enhanced compared to the normal group, the protein can be potentially targeted as an early biomarker to indicate risks of tobacco-related diseases 15.

Saliva contains biomarkers derived from serum, gingival crevicular fluid, and mucosal transudate which are useful in multiplexed assays that are being developed as point-of-care devices, rapid tests, or in more standardized formats for centralized clinical laboratory operations 16. The prospect of salivary diagnosis appeals to many scientists around the world for disease prognosis and diagnosis. Current discoveries on potential salivary biomarkers encompass various systemic diseases such as autoimmune diseases, bone turnover markers, cardiovascular markers, dental caries and periodontal diseases, diseases of the adrenal cortex, drug level monitoring, forensic evidence, genetic disorders, infections, malignancy, occupational and environmental medicine, psychological research, and renal diseases 17. In oral squamous cell carcinoma, Ni et al. 18 acquired several potential salivary biomarkers corresponding to early detection and evaluation of aggressiveness and occurrence of the cancer based on recent researches. As such, further salivary investigation can yield more comprehensive information about this fluid especially in the field of health medicine.

Apart from genomics and metabolomics, salivary proteomics 19 has demonstrated a great potential and has been widely utilised as a means to identify candidate biomarkers and possible immunochemistry markers for various illnesses predominantly infectious and neoplastic diseases 20. In peptide identification, Mass Spectrometry (MS)-based proteomic techniques have been commonly applied including two-dimensional gel electrophoresis-mass spectrometry (2-DE/MS), liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF/MS), and surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (SELDI-ToF/MS) 21. By employing one of MS-based proteomic techniques, Chan et al. 22 detected significant altered abundance of polymeric immunoglobulin receptor, plastin-2, actin related protein 3, leukocyte elastase inhibitor, carbonic anhydrases 6, immunoglobulin J, and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist among T2DM patients with periodontitis compared to their control T2DM cohorts. Additionally, Jessie et al. 23, 24 detected increased abundance and structural microheterogeneity of haptoglobin beta chains in the saliva of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma which were also subsequently observed in the saliva of habitual betel quid chewers. Many other salivary biomarkers with diagnostic potential were already characterised in oncology, head and neck carcinoma, breast and gastric cancers, salivary gland function and disease, Sjögren syndrome, systemic sclerosis, dental and gingival pathology, systemic, psychiatric, and neurological diseases using MS-based proteomics 25. It is possible that efficiency and accuracy of these proteomic technologies will turn salivary diagnostics into a clinical reality.

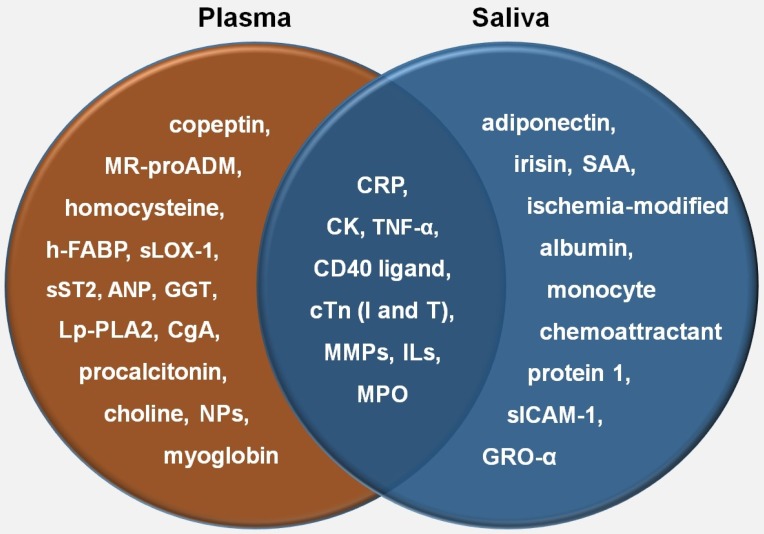

Salivary proteomes in relation to AMI

The prospect of utilizing saliva samples in the diagnosis of AMI is appealing to a large group of scientists due to its noninvasive and economical nature. Extensive biomarker research on CVD has elucidated various proteins associated with this disease. Since approximately 27% of the whole saliva proteins resemble those found in plasma 26, similar proteins present in both saliva and plasma will be very useful to facilitate monitoring of both disease progression and therapeutic treatments among these patients. In association with AMI, some studies on plasma proteins revealed significant biomarkers involved in myocardial injury, myocardial stress, inflammation, neuroendocrine activation, atherosclerotic process, platelet activation, plaque instability, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and myocardial stretch. Out of all these proteins, natriuretic peptides, C-reactive protein (CRP), creatine kinase (CK), and cardiac troponin were included as commonly used cardiac biomarkers in acute cardiac care 27. In a clinical setting, a kit for measuring human salivary CRP, a common biomarker related to cardiovascular inflammation, has been developed by Salimetrics®. Another recent cutting-edge technology is Oral Fluid NanoSensor Test (OFNASET) which provides portable, cheap, accurate, definitive, and quantitative results. Besides its intended use in oral cancer, this particular alternative can possibly benefit the point-of-care multiplex detection of salivary biomarkers among AMI patients 28. Given the above-mentioned clinical benefits of saliva collection, a patient's salivary proteome should be very useful in determining heart condition of the patient in order to predict AMI. Several studies have demonstrated salivary biomarkers associated with AMI, as shown in Table 1. By comparing these salivary biomarkers with those in plasma, as elaborated by Kossaify et al. 27, CRP, CK, CD40 ligand, cardiac troponin I, cardiac troponin T, some families of interleukin (IL), tumour necrosis factor alpha, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), and myeloperoxidase share similarities with plasma biomarkers which also play significant roles in inflammation and plaque instability (Figure 2). Although these discoveries may enlighten the diagnostic utility of salivary proteomes as biomarkers in relation to CVD, none of the salivary biomarkers listed above have been verified to predict the onset of AMI. All of these studies, as tabulated in table 1, were conducted retrospectively after the incidence. On the other hand, prospective studies should be able to alternatively facilitate the researchers to find predictive AMI biomarkers. In future, these newly detected salivary biomarkers will conceivably provide an early molecular diagnosis and eventually increase the survival rate of cardiovascular patients as opposed to that of plasma. However, more validation needs to be carried out in order to find robust and discriminatory biomarkers for this disease.

Table 1.

Salivary biomarkers associated with AMI.

| Significant Associated Proteins | Subjects | Methods | Saliva | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP, CK-MB, sCD40 ligand | 92 + 105 control | Beadlyte technology (Luminex®) and enzyme immunoassays | UWS | 29 |

| Decreased irisin, increased troponin-I, CK, CK-MB | 11 + 14 control | Enzyme immunoassay | Submandibular/ Sublingual/Parotid |

30 |

| Increased ischemia-modified albumin | 60 + 40 control | Colorimetric assay | UWS | 31 |

| Increased cTnI* | 30 + 28 control | Enzyme immunoassay | UWS/SWS | 32 |

| Increased hs-cTnT | 30 + 30 control | Enzyme immunoassay | UWS/SWS | 33 |

| Increased SAA | 85 + 388 control | Kinetic enzyme assay | UWS | 34 |

| Increased CK-MB | 30 + 30 control | Immunoinhibition assay | UWS | 35 |

| Increased CK | 30+ 30 control | IFCC | UWS | 36 |

| Increased polymorphonuclear leukocyte MMP-8 | 47 + 28 control | Immunofluorometric assay and immunoblot densitometric analysis | SWS | 37 |

| Increased CRP, MMP-9, IL-1β, sICAM-1, MPO, adiponectin, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, GRO-α, decreased TNF-α, sCD40 ligand, IL-6 | 41 + 43 control | Beadlyte technology (Luminex®) and enzyme immunoassays | UWS | 38 |

SWS: stimulated whole saliva; UWS: unstimulated whole saliva; sCD40: ligand soluble CD40 ligand; cTnI: cardiac troponin I; hs-cTnT: hyper-sensitivity cardiac troponin T: SAA: salivary alpha-amylase; IFCC: International Federation of Clinical Chemistry; MPO: myeloperoxidase; sICAM-1: soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1; GRO-α: growth-related oncogene-alpha; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor-alpha. *Only found in UWS

Figure 2.

Comparison of plasma and salivary biomarkers in relation to AMI. NP: natriuretic peptide; h-FABP: heart-type fatty-acid binding protein; MR-proADM: midregional-proadrenomedullin; CgA: chromogranin A; sLOX-1: soluble lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1; Lp-PLA2: lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; ANP: atrial natriuretic peptide; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor- alpha; cTn: cardiac troponin; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; MPO: myeloperoxidase; SAA: salivary alpha-amylase; GRO-α: growth related oncogene-alpha; sICAM-1: soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1

Susceptibility of AMI among patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus

T2DM is an inflammatory illness with a clear-cut relationship with CVD. This is validated when heart disease and stroke constitute no less than 70 percent of mortality among people with this metabolic disorder 39, rendering the T2DM patients to fall into a high-risk group to be later inflicted by AMI. In fact, prevalence of T2DM cases is becoming a worldwide threat. The incidence of this disease has alarmingly doubled over the last three decades 40. T2DM is initially preceded by insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, both of which are related with cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, lipid abnormalities, and endothelial dysfunction 41. Consequently, when the heart loses the ability to pump blood effectively, congestive heart failure occurs which is often contributory to the later onset of AMI. Haffner et al. 42 discovered that the risk of adults with T2DM to suffer from CVD is two to four times higher than that of adults without the disorder.

Between 2010 and 2030, the number of T2DM cases is projected to increase by 69% in developing countries and by 20% in developed countries 43. An upsurge projection of the number of T2DM adults in developing countries is strongly associated with adoption of Western lifestyle due to overconsumption of inexpensive, high-calorie food, and sedentary routine. The resulting potent obesity rapidly escalates the percentages of diabetic incidence in these developing nations which are already stricken under the burden of communicable diseases such as lower respiratory tract infections, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), diarrheal diseases, and others 44. To date, practitioners in the U.S. have recommended diverse cardiac tests to diagnose coronary heart disease despite the limitation that no individual test is sufficiently reliable 45. The tests may incorporate electrocardiogram, stress testing, echocardiography, chest x-ray, blood tests, electron-beam computed tomography, coronary angiography, and cardiac catherization. Thus far, none of these tests are adequately relevant to the prediction of infarction in the majority of individuals tested, even if their biochemical results are also supplemented to foresee the cardiac event. Likewise, in developing countries, the lofty costs of highly-trained practicioners, hospitalizations, and these tests are inherently unfeasible 46. For this reason, prospective patients from these regions are more likely to forgo the testing process and leave themselves undetected until reaching the chronic stage. Due to the reliability and inexpensive nature of saliva collection, salivary diagnosis can be easily aimed at these high-risk patients residing in developing regions. Consequently, this method is expected to revamp the current health system and increase the availability of accurate diagnostics in remote and impoverished areas.

In a proteomic research of salivary biomarkers, Rao et al. 47 identified 487 unique proteins correlated with T2DM of which 33% of these had not been previously reported in human saliva. Sixty-five proteins were markedly expressed between control and T2DM samples predominantly involved in regulating metabolism and immune response pathways. Even though extensive studies have been conducted by scientists around the globe pertaining to respective diseases of T2DM and AMI, it is still paramount for the practitioners to be able to predict the onset of AMI among T2DM patients due to its strong propensity. A review conducted by Syed Ikmal et al. suggested YKL-40, alpha-hydroxybutyrate, soluble CD36, leptin, resistin, interleukin-18, retinol binding protein-4, and chemerin, some of which may be present in saliva, could act as predictors of cardiovascular events in diabetic patients. 48. Practically, a T2DM patient diagnosed with an enhanced level of any clotting proteins or inflammatory markers in saliva should be regularly monitored for an early intervention prior to the onset of AMI. In future, the generated database of these biomarkers will provide an instructive reference to assess the susceptibility of T2DM patients to heart condition, hence reducing morbidity and mortality associated with AMI and improving the quality of life of the patients predominantly from developing nations.

Current challenges

Saliva diagnostic tests can be potentially used within a wide range of clinical applications including population-based screening programs, confirmatory diagnosis, risk stratification, prognosis determination, and therapy response monitoring. Nevertheless, decreasing the number of false-negative and false-positive test result outcomes should be invariably taken into consideration in order to maintain the quality of patient diagnosis and therapy 49.

In certain cases, some salivary proteomes may be spuriously discovered as biomarkers within a large pool of samples. One reason is certain peptides may have been subjected to modifications resulting to polymorphic isoforms and post translational modifications 50. Numerous salivary proteins were revealed to exist in polymorphic forms. For instance, genetic polymorphisms in CA6 gene influence the expression and catalytic activity of human salivary carbonic anhydrase VI 51. Protein degradation in whole saliva also plays a role in the variety of peptides observed. Takehara and her co-workers 52 proposed that the N-terminal region of mucin 7 was particularly prone to proteolytic degradation due to varying biological states of the human body. Another study conducted by Sun et al. 53 proved that many salivary glycoproteins were associated with age, gender, and immunity. It is also noteworthy that even though passive drooling, paraffin gum, and Salivette® collection methods cover whole saliva proteome, specific proteins observed are dependent on the collection approach 54.

In addition, older age is often associated with a number of cases related to functional limitations, heart failure, prior coronary disease, and renal insufficiency 55. As a result, saliva collection can pose a challenge among older T2DM patients. For example, geriatric patients are prone to xerostomia upon medications with anticholinergic properties, dehydration, diabetes, and radiotherapy for head and neck cancer 56. Dry mouth will limit the amount of sample collected and compromise its subsequent results. Insufficient sample volume obtained will possibly resort to loss of patients during the study. Some alternative sample collection approaches have been evaluated such as passive drool, filter paper, and microsponges but each individual approach has its own advantages and disadvantages in terms of sufficient sample recovery 57. Since there is no concrete resolution, the researcher has to be able to decide the best technique in accordance to the nature of research. It is also important to keep in mind that upon saliva collection, subsequent centrifugation for removing precipitated mucins and cellular contaminants will eliminate some proteins of interest. Despite incorporating accurate choice of collection system for easy quantification of volume with ample sample recovery, other essential standardisations of some preanalytical variables should always include precise and standardised collection schedules corresponding to individual hydration state, body posture, lighting, smoking status, circadian and circannual cycles, medications, food and visual stimulation, size of salivary glands, body weight, salivary flow index, physical exercise, alcohol intake, systemic diseases, nutrition, nausea, age, gender, and prevention of sample contamination with blood from oral mucosa and periodontal lesions 58.

Even though potential salivary biomarkers related to AMI were already discovered, other tests should be able to verify the presence of these proteins before its further applications. In clinical studies, biomarkers must be robust, distinguishable, and validated, particularly with regard to which biomarker is strongly linked to disease onset and progression. To achieve this goal, whole proteome-wide application and target biomarker discovery such as MS-based proteomics approaches will be able to provide an avenue due its higher sensitivity and accuracy in identifying and quantifying proteins than immunological assays 59.

Conclusions

There has been growing interest in diagnosis based on analysis of saliva due its simple and non-invasive collection procedure. Since saliva collection is inherently painless, practitioners will be able to diagnose and monitor the patients' wellbeing more frequently while approaching the sensitivity and specificity of a blood test. Plus, the collection is also cheap and safe for both the practitioner and patient. With that, patients especially from developing countries can be diagnosed with minimal costs but great precision.

In summary, human salivary proteomes exhibit promising potential as biomarkers to predict the onset of AMI particularly among its high-risk group of T2DM. Comprehensive analysis of human salivary proteome through various methods is indeed necessary in order to find the most reproducible markers for later utility in acute cardiac care. It is projected that salivary diagnostics will be conclusive such that fewer diagnostic biomarkers can be determined with immediate results, thus greatly improving the life quality of patients. In the long run, more available saliva collection kits developed by manufacturing companies will be able to aid and eventually provide solid biomarker findings in future.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by the PG110-2014A grant from IPPP, University of Malaya and Universiti Teknologi MARA Young Lecturer's Scheme awarded to Mohd Aizat Abdul Rahim.

Authors' Contribution

M.AA.R. conceived the idea, performed literature search, and wrote the paper.

Z.H.A.R. revised the paper from dental aspect.

W.A.W.A. revised the paper from clinical aspect.

O.H.H. revised the paper from proteomic aspect.

All authors approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- T2DM

type-2 diabetes mellitus CVD: cardiovascular disease

- MS

mass spectrometry

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CK

creatine kinase.

References

- 1.Punyadeera C. Saliva: an alternative to biological fluid for clinical applications. J Dento-Med Sci Res. 2013;1:2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao H, Wong DT. Proteomics and its applications for biomarker discovery in human saliva. Bioinformation. 2010;5:294–6. doi: 10.6026/97320630005294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiwari M. Science behind human saliva. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011;2:53–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.82322. doi:10.4103/0976-9668.82322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamster IB, Ahlo JK. Analysis of gingival crevicular fluid as applied to the diagnosis of oral and systemic diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1098:216–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.027. doi:10.1196/annals.1384.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iorgulescu G. Saliva between normal and pathological. Important factors in determining systemic and oral health. J Med Life. 2009;2:303–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majid S, Shafi M. Saliva as a diagnostic tool: a review. J Pharm Biol Sci. 2014;9:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarro MA, Mesía R, Díez-Gibert O, Rueda A, Ojeda B, Alonso MC. Epidermal growth factor in plasma and saliva of patients with active breast cancer and breast cancer patients in follow-up compared with healthy women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997;42:83–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1005755928831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence HP. Salivary markers of systemic disease: noninvasive diagnosis of disease and monitoring of general health. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:170–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis R, Goddard K, McCarty C, Feigelson H, Bulkley J, Rahm A. et al. Specimen collection within the CRN: a critical appraisal. THE HMO Cancer Research Network. 2010:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Joint ESCAAHAWHFTFftRoMI. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2173–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.011. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alwan A, Armstrong T, Bettcher D, Branca F, Chisholm D, Ezzati M, et al. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. In: WHO, editor. Burden, Mortality, Morbidity and Risk Ffactors. Canada: World Health Organization; 2011. pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullasari AS, Balaji P, Khando T. Managing complications in acute myocardial infarction. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong DT. Salivary diagnostics powered by nanotechnologies, proteomics and genomics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:313–21. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum BJ, Yates III JR, Srivastava S, Wong DTW, Melvin JE. Scientific frontiers: emerging technologies for salivary diagnostics. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:360–8. doi: 10.1177/0022034511420433. doi:10.1177/0022034511420433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jessie K, Pang WW, Rahim ZHA, Hashim OH. Proteomic analysis of whole human saliva detects enhanced expression of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, thioredoxin and lipocalin-1 in cigarette smokers compared to non-smokers. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:4488–505. doi: 10.3390/ijms11114488. doi:10.3390/ijms11114488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malamud D, Rodriguez-Chavez IR. Saliva as a diagnostic fluid. Dent Clin North Am. 2011;55:159–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2010.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malathi N, Mythili S, Vasanthi HR. Salivary diagnostics: a brief review. ISRN Dent. 2014;2014:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2014/158786. doi:10.1155/2014/158786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ni Y, Ding L, Hu Q, Hua Z. Potential biomarkers for oral squamous cell carcinoma: proteomics discovery and clinical validation. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2014 doi: 10.1002/prca.201400091. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceciliani F, Eckersall D, Burchmore R, Lecchi C. Proteomics in veterinary medicine: applications and trends in disease pathogenesis and diagnostics. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:351–62. doi: 10.1177/0300985813502819. doi:10.1177/0300985813502819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonne NJ, Wong DTW. Salivary biomarker development using genomic, proteomic and metabolomic approaches. Genome Med. 2012;4:1–12. doi: 10.1186/gm383. doi:10.1186/gm383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Q, Yu Q, Lin Q, Duan Y. Emerging salivary biomarkers by mass spectrometry. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;438:214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.08.037. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan HH, Rahim ZHA, Jessie K, Hashim OH, Taiyeb-Ali TB. Salivary proteins associated with periodontitis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:4642–54. doi: 10.3390/ijms13044642. doi:10.3390/ijms13044642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jessie K, Jayapalan JJ, Rahim ZHA, Hashim OH. Aberrant proteins featured in the saliva of habitual betel quid chewers: an indication of early oral premalignancy? Electrophoresis. 2014;00:1–8. doi: 10.1002/elps.201400252. doi:10.1002/elps.201400252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jessie K, Jayapalan JJ, Ong KC, Rahim ZHA, Zain RM, Wong KT. et al. Aberrant proteins in the saliva of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Electrophoresis. 2013;34:2495–502. doi: 10.1002/elps.201300107. doi:10.1002/elps.201300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castagnola M, Picciotti PM, Messana I, Fanali C, Fiorita A, Cabras T. et al. Potential applications of human saliva as diagnostic fluid. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:347–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loo JA, Yan W, Ramachandran P, Wong DT. Comparative human salivary and plasma proteomes. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1016–23. doi: 10.1177/0022034510380414. doi:10.1177/0022034510380414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kossaify A, Garcia A, Succar S, Ibrahim A, Moussallem N, Kossaify M. et al. Perspectives on the value of biomarkers in acute cardiac care and implications for strategic management. Biomark Insights. 2013;8:115–26. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S12703. doi:10.4137/BMI.S12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gau V, Wong D. Oral fluid nanosensor test (OFNASET) with advanced electrochemical-based molecular analysis platform. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1098:401–10. doi: 10.1196/annals.1384.005. doi:10.1196/annals.1384.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller CS, Foley III JD, Floriano PN, Christodoulides N, Ebersole JL, Campbell CL. et al. Utility of salivary biomarkers for demonstrating acute myocardial infarction. J Dent Res. 2014;93:72S–8S. doi: 10.1177/0022034514537522. doi:10.1177/0022034514537522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aydin S, Aydin S, Kobat MA, Kalayci M, Eren MN, Yilmaz M. et al. Decreased saliva/serum irisin concentrations in the acute myocardial infarction promising for being a new candidate biomarker for diagnosis of this pathology. Peptides. 2014;56:141–5. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.04.002. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toker A, Aribas A, Yerlikaya FH, Tasyurek E, Akbuga K. Serum and saliva levels of ischemia-modified albumin in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Lab Anal. 2013;27:99–104. doi: 10.1002/jcla.21569. doi:10.1002/jcla.21569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Riahi E. Salivary troponin I as an indicator of myocardial infarction. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:861–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Riahi E. Salivary high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T levels in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Oral Dis. 2013;19:180–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2012.01968.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2012.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen YS, Chen WL, Chang HY, Kuo HY, Chang YC, Chu H. Diagnostic performance of initial salivary alpha-amylase activity for acute myocardial infarction in patients with acute chest pain. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:553–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.040. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Hejazi SF, Riahi E, Salehi MM. Saliva-based creatine kinase MB measurement as a potential point-of-care testing for detection of myocardial infarction. Clin Oral Invest. 2012;16:775–9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0578-z. doi:10.1007/s00784-011-0578-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Jafari-Sabet M. Unstimulated whole saliva creatine phosphokinase in acute myocardial infarction. Oral Dis. 2011;17:597–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01817.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buduneli E, Mantyla P, Emingil G, Tervahartiala T, Pussinen P, Baris N. et al. Acute myocardial infarction is reflected in salivary matrix metalloproteinase-8 activation level. J Periodontol. 2011;82:716–25. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100492. doi:10.1902/jop.2010.100492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Floriano PN, Christodoulides N, Miller CS, Ebersole JL, Spertus J, Rose BG. et al. Use of saliva-based nano-biochip tests for acute myocardial infarction at the point of care: a feasibility study. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1530–8. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.117713. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2008.117713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laakso M. Hyperglycemia and cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48:937–42. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.937. doi:10.2337/diabetes.48.5.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, Singh GM, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ. et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants. Lancet. 2011;378:31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60679-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartol TG. The link between type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. Grapevine, Texas: John Hopkins Advanced Studies in Medicine; 2006. pp. 921–5. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. doi:10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hossain P, Kawar B, El Nahas M. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world - a growing challenge. N Eng J Med. 2007;356:213–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068177. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. How is heart disease diagnosed? http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/hdw/diagnosis.html.

- 46.Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Murphy A. (2010). Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35(2):72–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao PV, Reddy AP, Lu X, Dasari S, Krishnaprasad A, Biggs E. et al. Proteomic identification of salivary biomarkers of type-2 diabetes. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:239–45. doi: 10.1021/pr8003776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Syed Ikmal SI, Zaman Huri H, Vethakkan SR, Wan Ahmad WA. Potential biomarkers of insulin resistance and atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:698567.. doi: 10.1155/2013/698567. doi: 10.1155/2013/698567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfaffe T, Cooper-White J, Beyerlein P, Kostner K, Punyadeera C. Diagnostic potential of saliva: current state and future applications. Clin Chem. 2011;57:675–87. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.153767. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2010.153767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Messana I, Inzitari R, Fanali C, Cabras T, Castagnola M. Facts and artifacts in proteomics of body fluids. What proteomics of saliva is telling us? J Sep Sci. 2008;31:1948–63. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200800100. doi:10.1002/jssc.200800100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aidar M, Rocha Marques M, Valjakka J, Mononen N, Lehtimaki T, Parkkila S. et al. Effect of genetic polymorphisms in CA6 gene on the expression and catalytic activity of human salivary carbonic anhydrase VI. Caries Res. 2013;47:414–20. doi: 10.1159/000350414. doi:10.1159/000350414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takehara S, Yanagishita M, Podyma-Inoue KA, Kawaguchi Y. Degradation of MUC7 and MUC5B in human saliva. PloS One. 2013;8:e69059.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069059. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun S, Zhao F, Wang Q, Zhong Y, Cai T, Wu P. et al. Analysis of age and gender associated N-glycoproteome in human whole saliva. Clin Proteomics. 2014;11:25.. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-11-25. doi:10.1186/1559-0275-11-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golatowski C, Salazar MG, Dhople VM, Hammer E, Kocher T, Jehmlich N. et al. Comparative evaluation of saliva collection methods for proteome analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;419:42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.01.013. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mehta RH, Rathore SS, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. Acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: differences by age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:736–41. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Visvanathan V, Nix P. Managing the patient presenting with xerostomia: a review. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:404–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02132.x. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Granger DA, Kivlighan KT, Fortunato C, Harmon AG, Hibel LC, Schwartz EB. et al. Integration of salivary biomarkers into developmental and behaviorally-oriented research: problems and solutions for collecting specimens. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:583–90. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.004. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Almeida Pdel V, Grégio AM, Machado MA, de Lima AA, Azevedo LR. Saliva composition and functions: a comprehensive review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hale JE. Advantageous uses of mass spectrometry for the quantification of proteins. Int J Proteomics. 2013;2013:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/219452. doi:10.1155/2013/219452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]