Abstract

Background:

Heterotopic gastric-type epithelium, including gastric foveolar metaplasia (GFM) and gastric heterotopia (GH), is a common finding in duodenal biopsy specimens; however, there is still controversy regarding their histogenetic backgrounds.

Methods:

We analysed a total of 177 duodenal lesions, including 66 GFM lesions, 81 GH lesions, and 30 adenocarcinomas, for the presence of GNAS, KRAS, and BRAF mutations.

Results:

Activating GNAS mutations were identified in 27 GFM lesions (41%) and 23 GH lesions (28%). The KRAS mutations were found in 17 GFM lesions (26%) and 2 GH lesions (2%). A BRAF mutation was found in only one GFM lesion (2%). These mutations were absent in all 32 normal duodenal mucosa specimens that were examined, suggesting a somatic nature. Among the GFM lesions, GNAS mutations were more common in lesions without active inflammation. Analyses of adenocarcinomas identified GNAS and KRAS mutations in 5 (17%) and 11 lesions (37%), respectively. Immunohistochemically, all the GNAS-mutated adenocarcinomas diffusely expressed MUC5AC, indicating gastric epithelial differentiation.

Conclusions:

A significant proportion of GFM and GH harbours GNAS and/or KRAS mutations. The common presence of these mutations in duodenal adenoma and adenocarcinoma with a gastric epithelial phenotype implies that GFM and GH might be precursors of these tumours.

Keywords: Gastric foveolar metaplasia, gastric heterotopias, duodenum, GNAS, KRAS

The presence of gastric foveolar epithelium is a common finding in duodenal biopsy specimens. Depending on the absence or presence of oxyntic glands, these lesions are classified into gastric foveolar metaplasia (GFM) or gastric heterotopia (GH; Yantiss and Antonioli, 2009). GFM is generally regarded as a reactive process, as it is often associated with inflammatory conditions, including duodenal ulcer and chronic inflammatory diseases (Shousha et al, 1983; Wyatt et al, 1990; Khulusi et al, 1996). Previous studies characterised duodenal ulcer-associated epithelial phenotypes and suggested that GFM represents a reparative lineage histogenetically related to Brunner's glands (Hanby et al, 1993; Kushima et al, 1999a). On the other hand, GH consists of parietal and chief cells in addition to gastric foveolar epithelium and is morphologically indistinguishable from oxyntic gland mucosa of the stomach. Because of the fully organised structure of this lesion, many authors consider it to be congenital in nature (Lessells and Martin, 1982; Shousha et al, 1983; Wyatt et al, 1990).

Recent studies have demonstrated that several lesions that had been regarded as being metaplastic or hyperplastic in nature are actually associated with frequent genetic alterations. For example, colorectal hyperplastic polyps were thought to be metaplastic lesions, as they exhibit preserved overall crypt organisation and no epithelial dysplasia (Williams et al, 1980); however, later studies have shown that a significant proportion of colorectal hyperplastic polyps have an activating BRAF or KRAS mutation, and these lesions are now recognised as potential precursors of colorectal cancer (Iino et al, 1999; Hawkins and Ward, 2001; Chan et al, 2003; Yamada et al, 2012; Bettington et al, 2013). Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia 1A (PanIN1A) has also been previously regarded as a mucinous metaplasia; however, it is now thought to be the earliest stage precursor of invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Hruban et al, 2001). Furthermore, the demonstration of somatic mutations, mostly KRAS mutations, in virtually all PanIN1A lesions strongly suggests the requirement of these genetic alterations in their development (Kanda et al, 2012).

Interestingly, previous reports described the association of GFM and GH with duodenal adenoma and adenocarcinoma and suggested that some duodenal tumours, particularly those with a gastric epithelial phenotype, might arise from GFM or GH (Kushima et al, 1999b; Kushima et al, 2002; Ushiku et al, 2014). In the present study, we analysed a series of GFM and GH lesions for the presence of GNAS, KRAS, and BRAF mutations based on the postulation that a subset of these lesions might harbour genetic alterations, similar to colorectal hyperplastic polyps and PanIN1A. We selected these genes for analysis based on the frequent presence of these mutations in benign/low-grade tumours of the digestive tract, which exhibit gastric-type mucin expression (Chan et al, 2003; Furukawa et al, 2011; Wu et al, 2011; Kanda et al, 2012; Matsubara et al, 2013; Nishikawa et al, 2013).

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Center, Tokyo, Japan. All the tissue samples were obtained at the National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan, between 1998 and 2013. All the specimens were routinely fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and subjected to hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. The present study analysed a total of 177 duodenal lesions of 165 patients, including 66 GFM lesions, 81 GH lesions, and 30 nonampullary duodenal adenocarcinomas, as well as 32 specimens of normal duodenal mucosa (Figure 1). All specimens of GFM, GH, and normal duodenal mucosa were obtained by biopsy and cases with a history of duodenal tumours were excluded. Two endoscopists reassessed the endoscopic images to confirm the duodenal origins of these specimens. For the case of GFM and GH, biopsy specimens containing at least two pits lined by gastric-type epithelium were selected to ensure the reproducible PCR amplification. Adenocarcinoma samples were obtained by endoscopic mucosal resection (2 cases), or surgical resection (28 cases).

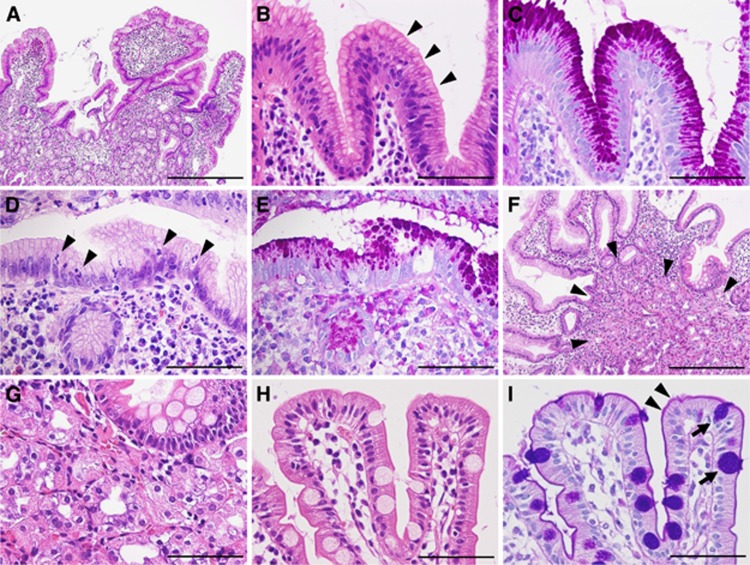

Figure 1.

Histology of gastric foveolar metaplasia, gastric heterotopia, and normal duodenal mucosa. (A–C) Gastric foveolar metaplasia. Gastric foveolar-type epithelium exhibiting remarkable hyperplasia (A). Note the surface papillary projections lined by gastric foveolar-type epithelium. The lining epithelium shows an apical mucin cap (arrowheads; B), which is positive for periodic-acid Schiff (PAS) staining (C). (D, E) Gastric foveolar metaplasia with active inflammation. Note the intraepithelial neutrophils (arrowheads; D). Epithelium showing PAS-positive apical mucin (E). (F, G) Gastric heterotopia. Oxyntic glands (arrowheads) are present beneath the gastric foveolar-type epithelium showing foveolar hyperplasia (F). Closely packed oxyntic glands consisting of parietal and chief cells (G). (H, I) Normal duodenal mucosa. Villi lined by intestinal epithelium with a brush border. Goblet cells are intermingled with the absorptive cells (H). The brush border is positive for PAS staining (purple, arrowheads), whereas the goblet cells are positive for Alcian blue (blue, arrows; I). Scale bars indicate 400 μm in (A and F) and 100 μm in (B–E and G–I).

Histological analysis

Sections of GFM and GH were subjected to alcian blue/periodic-acid Schiff (AB/PAS) double staining to confirm the presence of gastric foveolar epithelium with AB-negative/PAS-positive apical mucin. Subclassification into GFM and GH were made depending on the absence or presence of the oxyntic glands, respectively. The presence of active inflammation (characterised by intraepithelial neutrophils) and foveolar hyperplasia (defined by papillary growth associated with broad stroma) was assessed.

Immunohistochemistry was performed for the adenocarcinomas and representative GFM and GH lesions. Deparaffinized 4-μm thick sections from each paraffin block were exposed to 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Antigen retrieval was performed by autoclaving in a 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min. Anti-MUC2 (Ccp58; 1 : 200 dilution; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, England), anti-MUC5AC (CLH2; 1 : 200 dilution; Novocastra), anti-MUC6 (CLH5; 1 : 100, Novocastra), and anti-CDX2 (CDX2-88; 1 : 100; Bio Genex, San Ramon, CA, USA) were used as the primary antibodies. For staining, we used an automated stainer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) according to the vendor's protocol. ChemMate EnVision (Dako) methods were used for detection. The staining results were scored as: 0, <10% positive cells; 1+, 11%–50% positive cells; 2+, >50% positive cells.

Mutational analysis

Ten-micrometre sections of paraffin-embedded specimens were deparaffinized, stained briefly with hematoxylin, then subjected to DNA extraction. The lesions were microdissected using sterilised toothpicks under a microscope. The dissected samples were incubated in 50 μl of DNA extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20, 200 μg/ml proteinase K) at 50 °C overnight. Next, the samples were heated at 100 °C for 10 min to inactivate proteinase K and then directly subjected to a PCR assay using pairs of primers encompassing exon 8 and 9 of GNAS, exon 2, 3, and 4 of KRAS, and exon 15 of BRAF (Table 1). The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% (w/v) agarose gel and were recovered using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The isolated PCR products were sequenced using an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster, CA, USA). All mutations were confirmed by reanalysis of the respective specimens, including DNA extraction.

Table 1. Primer sequences.

| Gene | Region | Forward 5′-3′ | Reverse 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNAS | Exon 8 | GGCTTTGGTGAGATCCATTGAC | TGGCTTACTGGAAGTTGACTTTG |

| Exon 9 | GACATTCACCCCAGTCCCTCTGG | GAACAGCCAAGCCCACAGCA | |

| KRAS | Exon 2 | ACATGTTCTAATATAGTCACATTTTCA | TTAGCTGTATCGTCAAGGCA |

| Exon 3 | AGGATTCCTACAGGAAGCAAG | AAAGAAAGCCCTCCCCAGT | |

| Exon 4 | CTCTGAAGATGTACCTATGGTCCT | TTTCAGTGTTACTTACCTGTCTTGTC | |

| BRAF | Exon 15 | TGCTTGCTCTGATAGGAAAATG | CTGATGGGACCCACTCCAT |

Three GH samples that had GNAS mutations were further subjected to an analysis using a laser microdissection system (MMI CellCut system; Molecular Machines and Industries, Glattbrugg, Switzerland). The foveolar epithelium and oxyntic glands were separately dissected and analysed for the presence of GNAS mutations as described above.

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test was used to analyse each 2 × 2 table. P-values<0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The average ages of the patients with GFM, GH, and adenocarcinoma were 60 (range, 42–81 years), 57 (range, 25–84 years), and 64 years (range, 32–85 years), respectively. The presence of PAS-positive apical mucin was confirmed in all the GFM and GH lesions (Figure 1C and E). Evidence of active inflammation was observed in 14 GFM lesions (21%) and 1 GH lesion (1%) (Figure 1D and E). Twenty-one GFM lesions (32%) and eight GH lesions (10%) exhibited foveolar hyperplasia (Figure 1A and F).

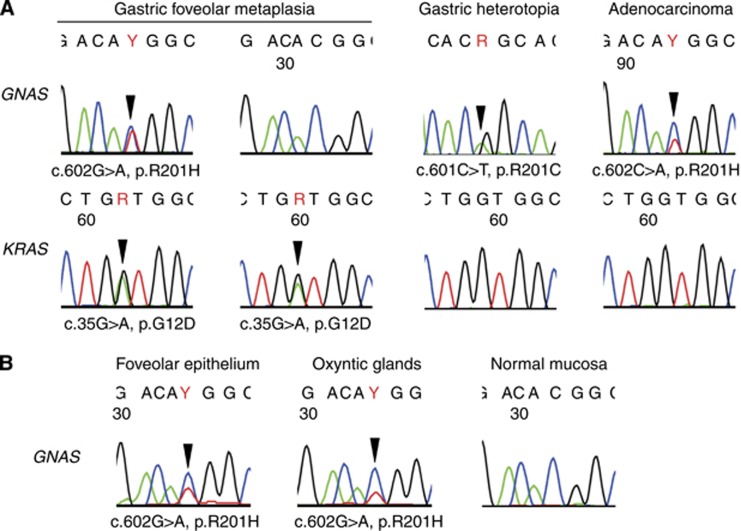

Sequencing analyses identified activating GNAS mutations in 27 GFM lesions (41%), 23 GH lesions (28%), and 5 adenocarcinomas (17% Table 2, Figure 2A). Activating KRAS mutations were found in 17 GFM lesions (26%), 2 GH lesions (2%), and 11 adenocarcinomas (37%). An activating BRAF mutation was found only in one GFM lesion (2%). None of the normal duodenal mucosa specimens showed any genetic alterations. Taken together, 36 GFM lesions (55%), 23 GH lesions (28%), and 15 adenocarcinomas (50%) harboured at least one of these genetic alterations (Table 3). Multiple independent lesions of GFM or GH were analysed in 10 patients. Among them, the mutational statuses of the lesions were discordant in six patients, confirming the multifocality of these lesions (Table 4).

Table 2. GNAS and KRAS mutations in duodenal lesions.

|

GNAS |

KRAS |

BRAF |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Total mutated | n | Nucleotide | Amino acid | Total mutated | n | Nucleotide | Amino acid | Total mutated | n | Nucleotide | Amino acid | |

| Normal | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Gastric foveolar metaplasia | 66 | 27 (41%) | 12 | c.601C>T | p.R201C | 17 (26%) | 1 | c.34G>C | p.G12R | 1 (2%) | 1 | c.1801A>G | p.K601E |

| 2 | c.601C>A | p.R201S | 3 | c.35G>A | p.G12D | ||||||||

| 13 | c.602G>A | p.R201H | 6 | c.35G>T | p.G12V | ||||||||

| 1 | c.35G>C | p.G12A | |||||||||||

| 1 | c.38G>A | p.G13D | |||||||||||

| 2 | c.183A>C | p.Q61H | |||||||||||

| 1 | c.183A>T | p.Q61H | |||||||||||

| 2 | c.437C>T | p.A146V | |||||||||||

| Gastric heterotopia | 81 | 23 (28%) | 11 | c.601C>T | p.R201C | 2 (2%) | 1 | c.35G>T | p.G12V | 0 | |||

| 1 | c.601C>A | p.R201S | 1 | c.35G>C | p.G12A | ||||||||

| 11 | c.602G>A | p.R201H | |||||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 30 | 5 (17%) | 1 | c.601C>T | p.R201C | 11 (37%) | 1 | c.34G>C | p.G12R | 0 | |||

| 3 | c.602G>A | p.R201H | 7 | c.35G>A | p.G12D | ||||||||

| 1 | c.680A>G | p.Q227R | 1 | c.35G>T | p.G12V | ||||||||

| 2 | c.38G>A | p.G13D | |||||||||||

N, Total number of lesions; n, number of lesions with mutations.

Figure 2.

GNAS and KRAS mutations in gastric foveolar metaplasia and gastric heterotopia. (A) Representative GNAS and KRAS mutations identified in gastric foveolar metaplasia, gastric heterotopia, and adenocarcinoma of the duodenum. (B) GNAS mutations in each epithelial component of gastric heterotopia. An identical missense mutation is present in both the foveolar epithelium and oxyntic glands. Missense mutations are indicated by arrowheads. GNAS was sequenced using reverse primers.

Table 3. Combined occurrence of GNAS and KRAS mutations in each duodenal lesion.

| Total number | GNAS(+)/KRAS(+) | GNAS(+)/KRAS(−) | GNAS(−)/KRAS(+) | GNAS(−)/KRAS(−) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric foveolar metaplasia | 66 | 8 (12%) | 19 (29%)* | 9 (14%) | 30 (45%) |

| Gastric heterotopia | 81 | 2 (2%) | 21 (26%) | 0 | 58 (72%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 30 | 1 (3%) | 4 (13%) | 10 (33%) | 15 (50%) |

One lesion had concurrent GNAS and BRAF mutations.

Table 4. GNAS and KRAS mutation statuses in multifocal lesions.

|

Mutation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Lesion | Histology | GNAS | KRAS |

| 11 | (1) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | — | — |

| (2) | Gastric heterotopia | — | — | |

| 20 | (1) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | c.601C>T | — |

| (2) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | c.602G>A | — | |

| (3) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | c.601C>T | — | |

| 30 | (1) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | — | — |

| (2) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | — | — | |

| (3) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | — | ||

| 48 | (1) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | — | c.35G>C |

| (2) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | c.601C>T | c.34G>C | |

| 53 | (1) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | — | c.183A>C |

| (2) | Gastric foveolar metaplasia | c.602G>A | c.183A>C | |

| 74 | (1) | Gastric heterotopia | c.601C>T | — |

| (2) | Gastric heterotopia | c.602G>A | — | |

| 84 | (1) | Gastric heterotopia | — | — |

| (2) | Gastric heterotopia | — | — | |

| 93 | (1) | Gastric heterotopia | — | — |

| (2) | Gastric heterotopia | — | — | |

| 105 | (1) | Gastric heterotopia | — | — |

| (2) | Gastric heterotopia | c.601C>T | — | |

| 115 | (1) | Gastric heterotopia | c.601C>T | — |

| (2) | Gastric heterotopia | c.602G>A | — | |

We further performed a microdissection-based analysis of the GH lesions to test for the presence of genetic alterations in two epithelial components: the foveolar epithelium and the oxyntic glands. A tissue sample sufficient for the analysis was available for three GH lesions with GNAS mutations. In all three lesions that were examined, identical GNAS mutations were detected in both the foveolar epithelium and the oxyntic glands (one lesion with c.601C>T and two lesions with c.602G>A; Figure 2B).

An examination of the correlations between the clinicopathological features and the mutational statuses showed that in the case of GFM lesions, both GNAS and KRAS mutations were significantly more common in lesions showing foveolar hyperplasia (Table 5). In the GH lesions as well, the presence of GNAS mutations was significantly associated with foveolar hyperplasia. Conversely, an inverse association was observed between the presence of GNAS mutations and the presence of active inflammation in the GFM lesions.

Table 5. Correlations among the presence of GNAS and KRAS mutations and the clinicopathological features.

|

Gastric foveolar metaplasia (N=66) |

Gastric heterotopia (N=81) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | GNAS mutation | P-value | KRAS mutation | P-value | Total number | GNAS mutation | P-value | KRAS mutation | P-value | |

|

Age | ||||||||||

| <65 | 31 | 10 (32%) | 0.22 | 9 (29%) | 0.59 | 43 | 10 (23%) | 0.33 | 2 (5%) | NA |

| ⩾65 | 35 | 17 (49%) | 8 (23%) | 38 | 13 (34%) | 0 | ||||

|

Site | ||||||||||

| Bulbs | 42 | 14 (33%) | 0.12 | 10 (23%) | 0.56 | 70 | 17 (24%) | 0.067 | 2 (3%) | NA |

| Others | 24 | 13 (54%) | 7 (30%) | 11 | 6 (55%) | 0 | ||||

|

Active inflammation | ||||||||||

| Present | 14 | 1 (7%) | 0.0047 | 2 (14%) | 0.72 | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0.28 | 0 | NA |

| Absent | 52 | 26 (50%) | 15 (29%) | 80 | 22 (28%) | 2 (3%) | ||||

|

Foveolar hyperplasia | ||||||||||

| Present | 21 | 16 (76%) | 1.1 × 10−4 | 9 (43%) | 0.039 | 8 | 7 (88%) | 4.6 × 10−4 | 2 (25%) | NA |

| Absent | 45 | 11 (24%) | 8 (18%) | 73 | 16 (22%) | 0 | ||||

P-values were assessed by Fisher's exact test. N, number of cases; NA, not assessed.

The adenocarcinomas were immunohistochemically examined for gastric and intestinal epithelial markers and the results were further analysed for correlations with the GNAS and KRAS mutation statuses (Table 6, Supplementary Figure 1 and 2, Supplementary Table 1). These results showed that the presence of GNAS mutations was significantly associated with the expression of MUC5AC (gastric foveolar mucin) and inversely correlated with the expression of CDX2 (intestinal transcription factor). No significant correlation with the expression of MUC6 (pyloric and Brunner's gland mucin) or MUC2 (major intestinal goblet cell mucin) was observed. KRAS mutations were not associated with the expression of any of the markers.

Table 6. Expression of gastric and intestinal epithelial markers and genetic alterations in adenocarcinoma.

|

Gastric epithelial markers |

Intestinal epithelial markers |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MUC5AC |

MUC6 |

MUC2 |

CDX2 |

|||||||||

| 2+ | 1+ | 0 | 2+ | 1+ | 0 | 2+ | 1+ | 0 | 2+ | 1+ | 0 | |

|

GNAS | ||||||||||||

| Mutated | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Wild type | 8 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 6 | 17 | 2 | 5 | 18 | 14 | 7 | 4 |

| P-value | 0.009 |

0.13 |

1.0 |

0.045 |

||||||||

|

KRAS | ||||||||||||

| Mutated | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Wild type | 8 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 3 |

| P-value | 1.0 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.14 | ||||||||

The results of immunohistochemistry were scored as: +2, >50% positive cells; +1, 10%–50% positive cells; 0, <10% positive cells. P-values were assessed by Fisher's exact test (2+ vs 1+ or 0).

Discussion

Gastric foveolar metaplasia in the duodenum is generally regarded as a reactive process caused by inflammatory conditions (Shousha et al, 1983; Wyatt et al, 1990; Hanby et al, 1993; Khulusi et al, 1996; Kushima et al, 1999a). However, we identified recurrent GNAS and/or KRAS mutations in a significant proportion of GFM lesions, implying a potential role of these genetic alterations in the development of these lesions. All the mutations, including a rare BRAF K601E mutation, are known to be activating mutations and have been previously reported in various types of tumours (Chan et al, 2003; Ikenoue et al, 2003; Furukawa et al, 2011; Wu et al, 2011; Yamada et al, 2012; Matsubara et al, 2013; Nishikawa et al, 2013). Furthermore, both GNAS and KRAS mutations were more prevalent among GFM lesions associated with foveolar hyperplasia, suggesting that these genetic alterations induce the proliferation of metaplastic epithelium. Conversely, genetic alterations were rare among GFM lesions histologically associated with active inflammation. This observation indicates that these mutations do not have a major role in the development of inflammation-related GFM and is supportive of a reactive nature of these lesions. Overall, we interpreted these findings to suggest that GFM consists of a heterogeneous group of lesion that are related to at least two different conditions: genetic alterations and inflammation.

Gastric heterotopia is generally thought to be congenital in nature (Lessells and Martin, 1982; Shousha et al, 1983; Wyatt et al, 1990). However, unexpectedly, the present study identified GNAS and/or KRAS mutations in 28% of the GH lesions. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that these genetic alterations initiate the transdifferentiation of intestinal epithelium into well-organised oxyntic glands. Of note, these mutations were more frequently found in GH with foveolar hyperplasia. Therefore, these mutations might have occurred in the preexisting GH and led to foveolar hyperplasia. Thus, we think that the identification of GNAS and KRAS mutations does not necessarily exclude a congenital origin of GH. On the other hand, a microdissection-based analysis identified common GNAS mutations in both foveolar epithelium and oxyntic glands in three GH lesions. This suggests that GNAS mutations occurred in stem cells that can differentiate into both of the two epithelial components, but do not cause detectable morphological changes in oxyntic glands.

It should be noted that the prevalence of genetic alterations, particularly those in GFM, can differ considerably depending on the patient background. Considering the inverse association between the presence of genetic alterations and active inflammation in GFM, GNAS and KRAS mutations are expected to be less common among patients with peptic disorders. Also, our study analysed relatively large GFM and GH lesions to facilitate reproducible genetic analyses. It is conceivable that minute GFM lesions, which are more commonly encountered in daily diagnostic situations, might have a different mutational prevalence.

GNAS and KRAS mutations were identified in 17 and 37% of the duodenal adenocarcinomas. Consistent with our results, a previous study reported the occurrence of KRAS mutations in 32% of duodenal adenocarcinomas (Fu et al, 2012). To our knowledge, there have been no previous studies of GNAS mutations in duodenal adenocarcinoma. Interestingly, all the GNAS-mutated adenocarcinomas diffusely expressed MUC5AC, a gastric foveolar mucin, and showed focal or no expression of CDX2, an intestinal transcription factor. On the other hand, no association was found between the expression of any of these markers and KRAS mutations. These findings indicate that GNAS mutations are more common in duodenal adenocarcinomas with a gastric epithelial phenotype, whereas KRAS mutation is not specifically related to either gastric or intestinal epithelial differentiation. Remarkably, previous reports have described the occurrence of GFM and GH in association with duodenal adenocarcinoma and have suggested that adenocarcinomas with a gastric epithelial phenotype might arise from GFM and GH (Kushima et al, 2002; Ushiku et al, 2014). Ushiku et al (2014) further reported that GFM and GH are often associated with adenocarcinomas with a gastric epithelial phenotype, but not with those with an intestinal epithelial phenotype.

In addition, several lines of evidence also imply a potential histogenetic link between GFM and GH and a particular subtype of duodenal adenoma. Pyloric gland adenoma, which is characterised by a gastric epithelial phenotype, can also be associated with GH (Kushima et al, 1999b). Furthermore, our previous study demonstrated the common presence of GNAS mutations in duodenal pyloric gland adenomas (Matsubara et al, 2013). On the other hand, GNAS mutations were absent in intestinal-type adenoma, which is a more common type of adenoma characterised by an intestinal epithelial phenotype (Matsubara et al, 2013). Considering the shared presence of GNAS mutations and the common phenotypic features, GFM and GH with genetic alterations might be potential precursors of pyloric gland adenoma and gastric-type adenocarcinoma. However, the rarity of duodenal tumours with a gastric epithelial phenotype, in contrast to the relatively common presence of GFM and GH, suggests that tumorigenesis from GFM and GH is an infrequent event.

The present study demonstrated the presence of recurrent GNAS and KRAS mutations in GFM and GH lesions in the duodenum. In contrast to the general understanding, a subset of GFM and GH lesions, particularly those unassociated with active inflammation, harbour genetic alterations. Importantly, pyloric gland adenoma and adenocarcinoma of the duodenum frequently have common genetic alterations, suggesting that GFM and GH are potential precursors of these duodenal neoplasms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Sachiko Miura and Ms Chizu Kina for skillful technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bettington M, Walker N, Clouston A, Brown I, Leggett B, Whitehall V. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013;62 (3:367–386. doi: 10.1111/his.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan TL, Zhao W, Leung SY, Yuen ST, Cancer Genome P BRAF and KRAS mutations in colorectal hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63 (16:4878–4881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu T, Pappou EP, Guzzetta AA, Jeschke J, Kwak R, Dave P, Hooker CM, Morgan R, Baylin SB, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Wolfgang CL, Ahuja N. CpG island methylator phenotype-positive tumors in the absence of MLH1 methylation constitute a distinct subset of duodenal adenocarcinomas and are associated with poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18 (17:4743–4752. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Kuboki Y, Tanji E, Yoshida S, Hatori T, Yamamoto M, Shibata N, Shimizu K, Kamatani N, Shiratori K. Whole-exome sequencing uncovers frequent GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Sci Rep. 2011;1:161. doi: 10.1038/srep00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanby AM, Poulsom R, Elia G, Singh S, Longcroft JM, Wright NA. The expression of the trefoil peptides pS2 and human spasmolytic polypeptide (hSP) in 'gastric metaplasia' of the proximal duodenum: implications for the nature of 'gastric metaplasia'. J Pathol. 1993;169 (3:355–360. doi: 10.1002/path.1711690313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Sporadic colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability and their possible origin in hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93 (17:1307–1313. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.17.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Compton C, Garrett ES, Goodman SN, Kern SE, Klimstra DS, Kloppel G, Longnecker DS, Luttges J, Offerhaus GJ. Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a new nomenclature and classification system for pancreatic duct lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25 (5:579–586. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino H, Jass JR, Simms LA, Young J, Leggett B, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H. DNA microsatellite instability in hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps: a mild mutator pathway for colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52 (1:5–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikenoue T, Hikiba Y, Kanai F, Tanaka Y, Imamura J, Imamura T, Ohta M, Ijichi H, Tateishi K, Kawakami T, Aragaki J, Matsumura M, Kawabe T, Omata M. Functional analysis of mutations within the kinase activation segment of B-Raf in human colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63 (23:8132–8137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda M, Matthaei H, Wu J, Hong SM, Yu J, Borges M, Hruban RH, Maitra A, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Goggins M. Presence of somatic mutations in most early-stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2012;142 (4:730–733 e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khulusi S, Badve S, Patel P, Lloyd R, Marrero JM, Finlayson C, Mendall MA, Northfield TC. Pathogenesis of gastric metaplasia of the human duodenum: role of Helicobacter pylori, gastric acid, and ulceration. Gastroenterology. 1996;110 (2:452–458. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushima R, Manabe R, Hattori T, Borchard F. Histogenesis of gastric foveolar metaplasia following duodenal ulcer: a definite reparative lineage of Brunner's gland. Histopathology. 1999;35 (1:38–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushima R, Ruthlein HJ, Stolte M, Bamba M, Hattori T, Borchard F. 'Pyloric gland-type adenoma' arising in heterotopic gastric mucosa of the duodenum, with dysplastic progression of the gastric type. Virchows Arch. 1999;435 (4:452–457. doi: 10.1007/s004280050425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushima R, Stolte M, Dirks K, Vieth M, Okabe H, Borchard F, Hattori T. Gastric-type adenocarcinoma of the duodenal second portion histogenetically associated with hyperplasia and gastric-foveolar metaplasia of Brunner's glands. Virchows Arch. 2002;440 (6:655–659. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0615-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessells AM, Martin DF. Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the duodenum. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35 (6:591–595. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.6.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara A, Sekine S, Kushima R, Ogawa R, Taniguchi H, Tsuda H, Kanai Y. Frequent GNAS and KRAS mutations in pyloric gland adenoma of the stomach and duodenum. J Pathol. 2013;229 (4:579–587. doi: 10.1002/path.4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa G, Sekine S, Ogawa R, Matsubara A, Mori T, Taniguchi H, Kushima R, Hiraoka N, Tsuta K, Tsuda H, Kanai Y. Frequent GNAS mutations in low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Br J Cancer. 2013;108 (4:951–958. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shousha S, Spiller RC, Parkins RA. The endoscopically abnormal duodenum in patients with dyspepsia: biopsy findings in 60 cases. Histopathology. 1983;7 (1:23–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushiku T, Arnason T, Fukayama M, Lauwers GY. Extra-ampullary duodenal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38 (11:1484–1493. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GT, Arthur JF, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. Metaplastic polyps and polyposis of the colorectum. Histopathology. 1980;4 (2:155–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1980.tb02909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, Dal Molin M, Wood LD, Eshleman JR, Goggins M, Canto MI, Schulick RD, Edil BH, Wolfgang CL, Klein AP, Diaz LA, Jr, Allen PJ, Schmidt CM, Kinzler KW, Papadopoulos N, Hruban RH, Vogelstein B. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3 (92:92ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt JI, Rathbone BJ, Sobala GM, Shallcross T, Heatley RV, Axon AT, Dixon MF. Gastric epithelium in the duodenum: its association with Helicobacter pylori and inflammation. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43 (12:981–986. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.12.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Sekine S, Ogawa R, Taniguchi H, Kushima R, Tsuda H, Kanai Y. Frequent activating GNAS mutations in villous adenoma of the colorectum. J Pathol. 2012;228 (1:113–118. doi: 10.1002/path.4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yantiss R, Antonioli D.2009Polyps of the Small Intestine Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Billiary Tract, and PancreasOdze R, Goldblum J (eds) 2 edn, Chapter 18 pp447–480.Elsevier: Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.