Abstract

In view of the importance of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs) in tumor staging and patient management, sensitive and accurate imaging of SLNs has been intensively explored. Along with the advance of the imaging technology, various contrast agents have been developed for lymphatic imaging. In this review, the lymph node imaging agents were summarized into three groups: tumor targeting agents, lymphatic targeting agents and lymphatic mapping agents. Tumor targeting agents are used to detect metastatic tumor tissue within LNs, lymphatic targeting agents aim to visualize lymphatic vessels and lymphangionesis, while lymphatic mapping agents are mainly for SLN detection during surgery after local administration. Coupled with various signal emitters, these imaging agents work with single or multiple imaging modalities to provide a valuable way to evaluate the location and metastatic status of SLNs.

Keywords: Sentinel lymph node, contrast agent, PET, MRI, fluorescence, imaging.

Introduction

Besides removing interstitial fluid from tissues to maintain tissue interstitial pressure, the lymphatic system plays a very important role in immune response by providing a transport route for antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and white blood cells 1. At the same time, it serves as a transport route for disseminating tumor cells, resulting in metastases. Although the exact mechanism is not clear, it is well taken that the lymphatics has advantages over the blood circulation for tumor metastasis, possibly due to the large cavity of lymph vessels and slow velocity of lymph 2. Consequently, many types of malignant tumors such as breast cancer, melanoma, and prostate cancer are prone to metastasize first to regional lymph nodes (LNs), through tumor associated lymphatic channels 3, 4.

The amount of spread to nearby lymph nodes is one of the components for TNM staging system, which has been accepted by the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). In addition, the status of the tumor draining LNs or sentinel LNs (SLNs) serves as an indicator of prognosis and therapeutic decision-making 5, 6. So far, the gold standard to stage the LNs is lymphadenectomy and histologic evaluation, which is invasive and limited by surgical field for nodal sampling and lack of accuracy 7. With the development of imaging techniques, currently, pre-surgical diagnosis of SLNs is often based on their morphologic change observed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or x-ray computed tomography (CT). The application and limitation of these imaging modalities have been summarized in details elsewhere 8.

Since the current assessment of lymph nodes relies on morphology and anatomy rather than function and physiology, tumor metastasis is mainly evaluated based on the size and the shape of the involved lymph node 9. However, nodal metastases are often microscopic, so neither CT nor MRI can rule them out reliably 10. Besides, it is very challenging for CT and MRI to visualize SLNs when they are small or have similar signal intensities with surrounding healthy soft tissues 11. Consequently, various imaging probes have been developed with the aim to better visualize and characterize the lymphatics 12. Based on imaging purpose and underlying mechanisms, these probes can be categorized into three classes, including tumor targeting agents, lymphatic targeting agents and lymphatic mapping agents.

Tumor targeting agents

As the name indicates, tumor targeting agents recognize specific biomarkers, pathways on/within tumor cells or tumor microenvironment to achieve tumor/non-tumor signal contrast for tumor visualization. Majority of tumor targeting agents are labeled with radionuclides for either single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET). For example, fluorine-18 labeled fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG), a glucose analog, usually shows high tumor accumulation due to the increased rate of glycolysis in various malignant cells 13-15. So far, 18F-FDG is the most valuable PET imaging tracer in clinical oncology and it is well accepted that FDG-PET is superior to morphologic imaging procedures for staging LNs adjacent to tumors (Figure 1) 16-18. The high uptake of FDG in tumor metastasized LNs also allows Cerenkov luminescence imaging with a specially designed dark box 17, which may be used to provide intraoperative guidance in the detection of positive lymph nodes. Due to the extremely low yield of Cerenkov photon, clinical value of this method will need further validation.

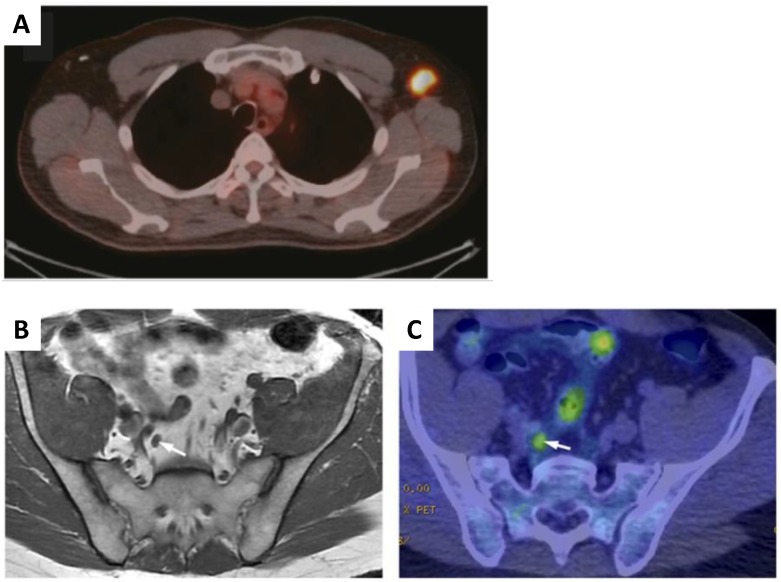

Figure 1.

A, A representative PET/CT images of 18F-FDG-positive axillary lymph node. B & C, Results for discordant false-negative MR imaging and true-positive 11C-choline PET/CT with a score for T1-weighted MR imaging of 3 (B) and a score for 11C-choline PET/CT of 5 (C) for LN metastasis are shown. The right internal iliac LN was indicated by arrow. (Reprinted and modified with the permission from references 17 and 24).

However, increased 18F-FDG uptake is not only observed in malignant tumors but also in inflammation and infection. Especially, the lack of specificity results in inaccurate identification of malignant lymph nodes in the mediastinum, which have been confirmed by numerous clinical studies 8. Low FDG uptake in certain cancer types also encourages looking into alternative imaging tracers. Prostate cancer is characterized by an increased uptake of choline into the cell to meet increased synthesis of phosphatidylcholine, an important cell membrane phospholipid. Therefore, choline, labeled either with 18F or 11C, has been used for PET imaging of prostate cancer 19-22. 11C-choline could detect LN metastasis from prostate cancer with a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 96%, and accuracy of 93% 23. In a recent clinical study in patients with prostate cancer, 11C-choline PET/CT was found to be superior for pelvic LN metastasis than multi-parametric MR imaging (Figure 1) 24. Increased lipid synthesis in prostate cancer also results in high retention of 11C-acetate or 18F-acetate. It has been demonstrated that 11C-acetate is better than 18F-FDG in detecting local recurrences and regional lymph node metastases of prostate cancer 25. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is significantly overexpressed on the surface of prostate cancer cells 26. It has also been reported that PSMA PET/CT using a 68Ga-labeled PSMA ligand can detect lesions characteristic of prostate cancer with improved contrast when compared to 18F-fluoromethylcholine PET/CT, especially at low PSA levels 27. These results suggest that PSMA targeting imaging may be useful in detection of lymph node metastases of prostate cancer.

Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) is a 40-kDa type I transmembrane protein found on epithelial cells. Overexpression of EpCAM was found in many metastasizing epithelial cancers 28, 29 and has been shown to be associated with the recurrence of prostate cancer 30. In view of these facts, Hall et al. 31 developed and labeled monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against EpCAM with a positron emitter, 64Cu and a near-infrared fluorophore, IRDye800 for both noninvasive and intraoperative detection of metastatic LNs in a prostate cancer model. Between 18 and 24 h post intravenous injection, tumor metastases in LNs can be clearly visualized with both PET and optical imaging (Figure 2).

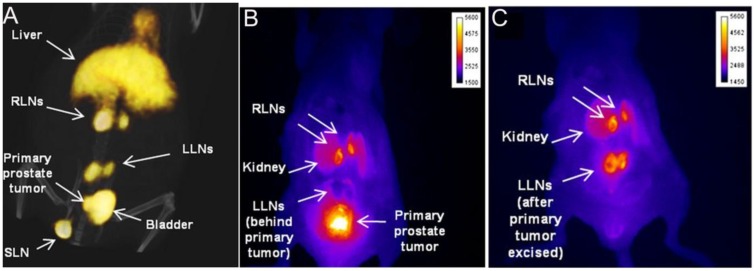

Figure 2.

Noninvasive small-animal PET/CT and invasive NIR fluorescence images of representative mouse having primary prostate tumor and metastatic LNs. An anti-EpCAM mAb was conjugated with DOTA for 64Cu radiolabeling and IRDye 800CW as a fluorophore. Within 18-24 h after intravenous injection of the tracer, noninvasive small-animal PET/CT was performed and immediately followed by in vivo NIRF optical imaging. A, Three-dimensional view from small animal PET/CT showed radiotracer signal in prostate region and several LNs. B &C, In situ NIR fluorescence images of ventral view from same animal confirmed presence of primary prostate tumor and cancer positive lumbar LNs and renal LNs. LLN = lumbar LN; RLN = renal LN; SLN = sciatic LN. (Reprinted and modified with the permission from reference 31).

Integrins are a family of 24 trans-membrane proteins which mediate cell-cell adhesion and attachment of cells to extracellular matrix (ECM) 32. Among them, αvβ3 integrin has been intensively investigated as a target for angiogenesis imaging and therapy of various types of tumors, owing to its positive role in regulating the survival of endothelial cells and promoting angiogenesis in malignant diseases 33-36. One dominant category of imaging probes were based on the peptide ligand of integrin αvβ3 with the sequence of arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) 37-40. Several RGD based tracers are in different phases of clinical trials 41. In one small scale clinical study using 18F-galacto-RGD, lymph-node metastases were detected in 3 of 8 patients 42. In another study using 99mTc-3PRGD2 SPECT, the primary lesions within lung and mediastinum could be detected along with most of the lymph node metastases 43.

Theoretically, any tumor targeting agent can be used to detect both primary tumors and metastases within LNs. Although with high sensitivity, the relatively low resolution (approximately 4-8 mm in clinical and 1-2 mm in small animal imaging systems) of PET limits its detection of micrometastases within LNs 44. The combination of PET and CT has matured into an important clinical diagnostic tool by providing anatomical and functional data sets in a single session with accurate image co-registration 45. A number of clinical studies demonstrated that sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of lymph node staging were all significantly improved with FDG-PET/CT compared with CT alone 46, 47. Recently, with the availability of PET/MRI, FDG PET/MR has been applied to lymphoma staging and showed high sensitivity and specificity for nodal involvement in lymphoma 48, 49. Even with these hybrid systems, novel tumor targeting probes with high sensitivity, specificity and signal contrast are still needed to visualize microscopic metastasis within LNs.

Lymphatic targeting agents

Tumor-induced lymph-angiogenesis (expansion of the lymphatic vasculature) in the tumor draining LNs usually precedes metastasis and leads to increased tumor spread to distal LNs and further to distal organs 50, 51. A number of lymphatic specific markers such as podoplainin, Prox-1, LYVE-1, and VEGFR-3 have been identified 52-54. Lymphatic targeting agents usually have been developed by labeling antibodies, or peptidic ligands against these lymphatic specific markers. For example, an IgM monoclonal antibody against the glycoproteins, which is responsible for recruiting lymphocytes into peripheral LNs 55, has been labeled with Cy7 dye for LN imaging. The dye conjugated antibody showed surprisingly high accumulation in peripheral LNs as early as 1 h after tail vein injection 56. The same antibody has been conjugated onto polymer shell microbubbles for LN detection using ultrasound imaging after intravenous administration 57.

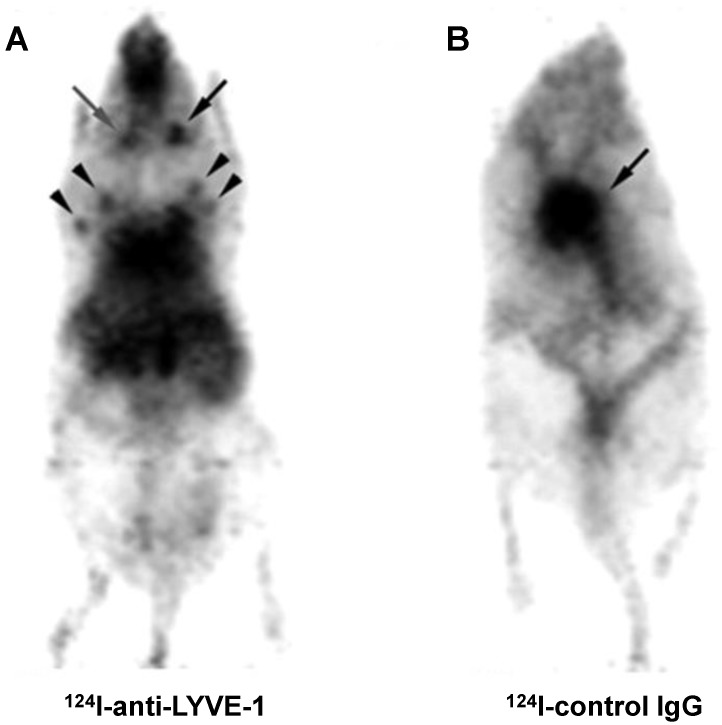

The lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor (LYVE-1) is expressed predominantly on lymphatic endothelium. As an ortholog of CD44, the function of LYVE-1 is to bind HA and regulate cell migration within the lymphatic system 58. Using an 124I-labeled antibody against LYVE-1, Mumprecht et al. 59 performed PET with mouse lymph-angiogenesis models and found that the LNs bearing metastases could be visualized by PET, even though the metastases were not detected by 18F-FDG PET (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

In vivo PET of inflammation-induced lymphangiogenesis in auricular LNs using 124I-anti-LYVE-1 antibody. A, the inflamed auricular LN (black arrow) accumulated more 124I-anti-LYVE-1 antibody than the contralateral control auricular LN (gray arrow). Brachial and axillary LNs were also detected (arrow heads). B, in vivo PET of a mouse injected with 124I-control IgG; the black arrow indicates the heart. (Reprinted and modified with the permission of reference 59).

Compared with antibodies, peptide-based imaging probes allow faster clearance due to much smaller molecular size. Lyp-1 is a cyclic 9-amino-acid cyclic peptide identified by in vivo phage display technology, which homes to lymphatic endothelial cells 54, 60. Intravenous administration of FITC-LyP-1 led to prominent accumulation in the tumor tissue 16-20 h after intravenous injection 61. The LyP-1 peptide has also been labeled with a near-infrared fluorophore Cy5.5 for optical imaging. Tumor-draining brachial LNs showed extensive growth of lymphatic sinuses throughout the cortex and medulla, indicating increased lymphangiogesis within these LNs 62.

Most approaches for cancer metastasis imaging in patients have focused on the detection of the cancer cells themselves 63, 64. As mentioned before, nodal metastases are often microscopic. It is very challenging to visualize the tumor tissue within the LNs either by anatomical imaging or molecular imaging using tumor targeting probes 65. Thus, the ability to detect LN lymphangiogenesis may serve as an alternative way to predict LN metastasis. However, lymphangiogenesis also happens under inflammatory stimulation since high levels of lymphangiogenic factors are produced by macrophages and granulocytes in inflamed tissue 66. One should be cautious about image interpretation since these lymphatic targeting agents would not differentiate tumor induced lymphangiogenesis from inflammatory reaction. This may be one of the main reasons why these lymphatic targeting agents have not been used in the clinic.

Lymphatic mapping agents

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is a surgical procedure to remove the lymph nodes from axilla for diagnosis and staging of breast cancer. Although it is the most accurate method to assess nodal status, ALND is associated with several adverse long-term side effects due to the extensive surgery. As an alternative, lymphatic mapping with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has emerged as an effective method to detect axillary metastases. Although still debatable, the clinical advantages of SLNB over ALND are apparent, and the procedure is becoming the preferred standard in patients with breast cancer or melanoma 67. Moreover, SLNB has become established clinical practice in patients with other types of cancer including penile, anal, colorectal and prostate cancer 68.

Different from the aforementioned imaging agents, lymphatic mapping agents are developed to meet the requirement of SLNB, i.e. to detect SLNs. Consequently, most of the imaging agents in this category are administered locally, which then migrate to and are trapped inside the SLNs. So far, the most commonly used lymphatic mapping method in the clinic is a combined injection of 99mTc-labeled colloids first and vital dyes (patent blue, isosulfan blue or indocyanine green (ICG)) several hours later. SLNs can be visualized pre-operationally either by gamma scintigraphy or SPECT. The SLNs during surgery could be located with a hand-held gamma ray counter and visual contrast of the blue dye. The value of this procedure has been substantiated in numerous clinical studies 69, 70.

However, this method has several drawbacks. Firstly, it requires separate administration of 99mTc-labeled colloids and dyes because of different rate of local migration 71. Secondly, scintigraphy and SPECT show relatively low sensitivity and spatial resolution. In addition, blue dye injections may stain the surgical field blue, which can be a hindrance during surgery 72. With the advancement of imaging instruments and material sciences, numerous lymphatic mapping probes have been developed, aiming to improve identification and mapping of lymph nodes, especially sentinel lymph nodes during surgery 73, 74.

To avoid injection of 99mTc-labeled colloid and blue colored vital dye separately, Evans blue (EB), a dye molecule binding with plasma proteins, has been labeled with 99mTc for SLNB. 99mTc-EB combines both radioactive and colored signals and can be administered as a single dose for SLN identification 75. To increase the migration rate and LN retention, 99mTc-tilmanocept has been developed, which consists of a dextran frame linked with multiple diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) for 99mTc labeling and mannose residues for CD206 binding. CD206 is a mannose receptor, primarily presented on the surface of macrophages and dendritic cells in lymph nodes 76. Because of its small size, 99mTc-tilmanocept can migrate quickly through the afferent lymph vessels and reside within SLNs due to the specific binding. Several clinical studies have confirmed that 99mTc-tilmanocept does not escape from the SLN to the second echelon lymph nodes, and has superior identification rates and sensitivity over blue dyes 68, 77. A hybrid fluorescent-radioactive tracer has also been applied for sentinel node identification by mixing ICG with 99mTc-labeled albumin nanocolloid 78. The lymphatic drainage pattern of ICG/99mTc-nanocolloid is identical to that of 99mTc-nanocolloid in clinical setting and all preoperatively identified sentinel nodes could be localized using combined radio- and fluorescence guidance intraoperatively.

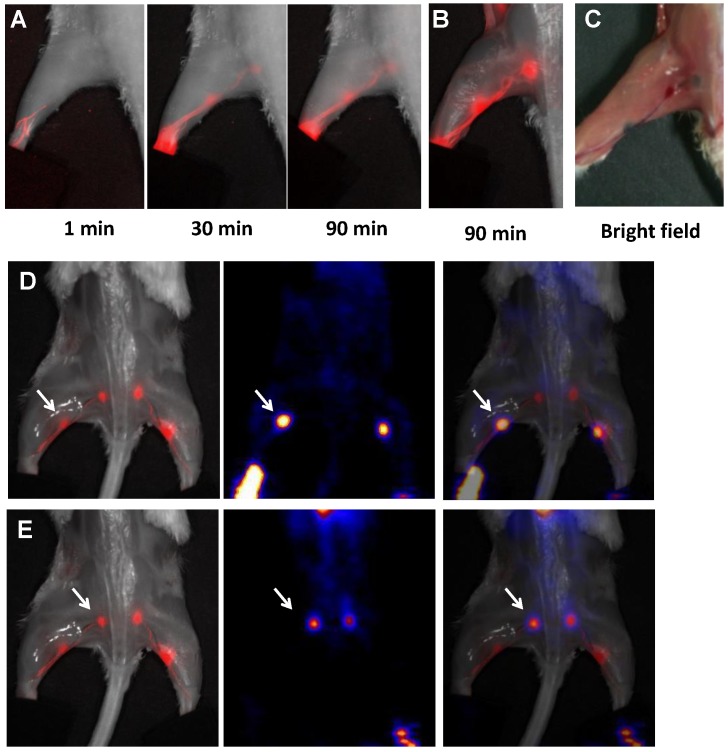

Compared with SPECT, PET has higher sensitivity and temporal resolution. PET lymphography has been investigated with intradermal administration of 18F-FDG for combined diagnostic and intraoperative visualization of LNs 79. Within 30 min after tracer injection, lymphatic vessels and LNs can be clearly revealed by PET in an animal modal. However, the clinical application of 18F-FDG PET lymphography may be challenged by the fast migration of the small molecules into blood circulation. Recently, we synthesized a NOTA (1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N',N''-triacetic acid) conjugated truncated Evans blue (NEB). 18F-labeling was achieved through the formation of 18F-aluminum fluoride complex 80. After intravenous injection, 18F-AlF-NEB complexes with serum albumin very quickly and thus most of the radioactivity is retained in the blood circulation 80. After local injection, 18F-AlF-NEB also forms complexes with endogenous albumin in the interstitial fluid and allows for visualizing the lymphatic system. The LNs can be distinguished clearly by high intensity PET signal from 18F-AlF-NEB (Figure 4) 81.

Figure 4.

A, Longitudinal fluorescence imaging of lymphatic system after hock injection of 18F-AlF-NEB/EB. LNs and lymphatic vessels can be clearly seen with the migration of the tracer along with time. B, Ex vivo optical imaging of LNs without skin. C, Photograph of the same mice to show the blue color within the LNs. D, Co-registration of optical image (left) and PET image (middle) to present the popliteal LNs, indicated by white arrow. E, Co-registration of optical image (left) and PET image (middle) to present the sciatic LNs, indicated by white arrow. The mice were euthanized at 90 min after hock injection of 18F-AlF-NEB/EB and skin removed. (Reprinted and modified with the permission from reference 136)

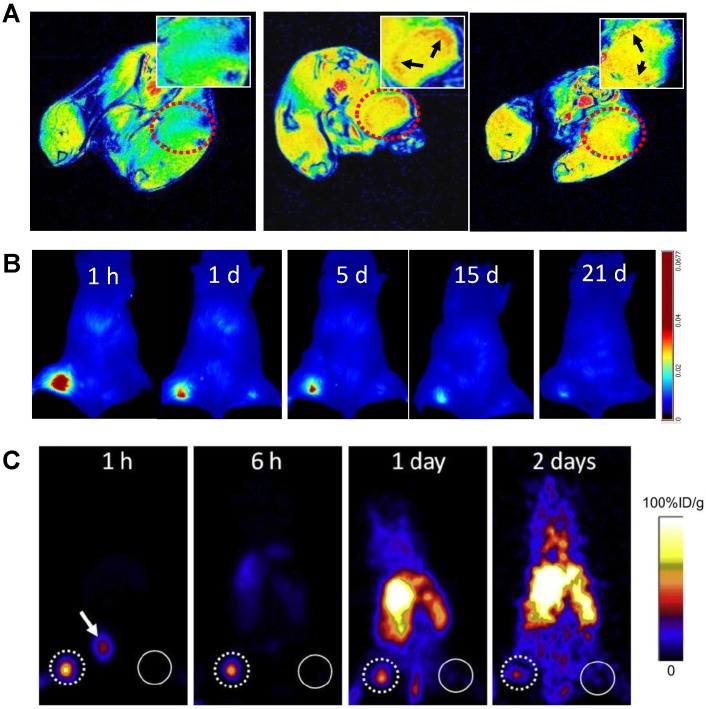

Superb spatial resolution endows MRI the ability to accurately reflect the anatomical location and resolve heterogeneity within LNs. After local administration of superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO), the adjacent LNs can be visualized on T2-weighted MRI since significant amount of particles is accumulated within the LNs, mainly through macrophage endocytosis 82, 83. More importantly, tumor metastasis can be distinguished by heterogeneous signal enhancement because metastatic tumor tissue takes up SPIO much less efficiently than the lymphatic tissue (Figure 5) 84, 85.

Figure 5.

A, MRI of sentinel lymph nodes in a 4T1 murine breast cancer tumor metastatic model before (left) and after injection of MSN-nanoprobes for 1 day (middle) and 15 days (right). Arrows denote the accumulation area of particles. B, optical imaging of tumor metastatic lymph nodes after injection of MSN-nanoprobes at different time points (1 h, 1 day, 5 days, 15 days and 21 days). C, PET imaging of sentinel lymph nodes in a 4T1 tumor metastatic model after injection of particles for 1 h, 6 h, 1 day and 2 days. Tumor draining lymph nodes are circled by dotted line and the contralateral lymph node circled by solid line. Arrow denotes bladder. (Reprinted and modified with the permission from reference 85).

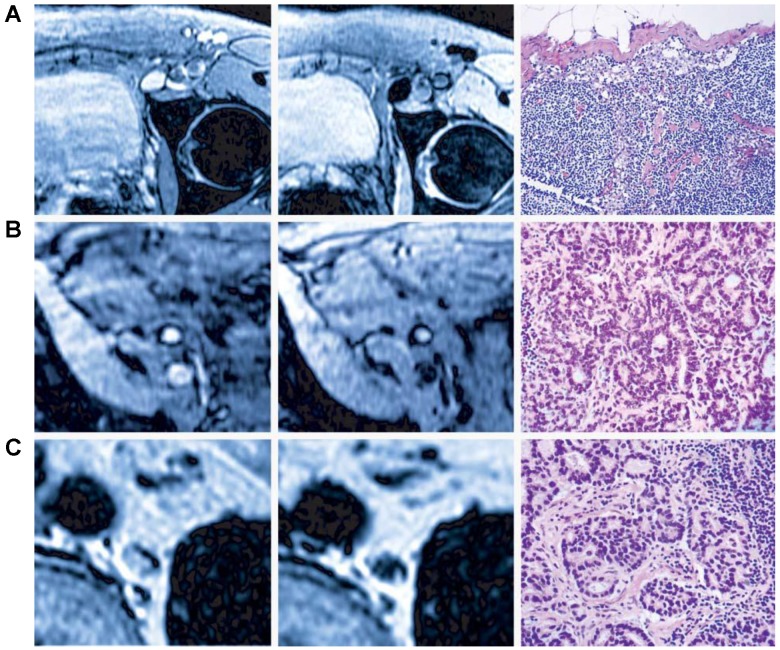

In some special cases when whole body LNs need be evaluated, intravenous administration may be preferred. After intravenous injection, some small sized (30-50 nm) lymphotropic nanoparticles such as ultrasmall SPIO (USPIO) are slowly extravasated from the vasculature into the interstitial space, from which they are transported to lymph nodes by way of lymphatic vessels 86. Accumulation of nanoparticles in benign nodes causes a decrease in signal intensity on T2-weighted and T2*-weighted MRI scans 86. The metastasized tumor tissue in malignant lymph nodes lacking normal macrophages cannot phagocytose USPIO and thus retain the bright signals in MRI scans 87. Consequently, in patients with prostate cancer, nodal metastases could be correctly identified in all patients with a significantly higher sensitivity than conventional MRI or nomograms (Figure 6) 88. One disadvantage of this imaging strategy is the slow transport of USPIO particles to the lymphatic system so delayed imaging at 24-36 h after contrast agents injection is necessary 89. In addition, low sensitivity of MRI requires relatively large amount of imaging contrast agents 90. Unpredictability of iron-induced susceptibility artifacts, and the heterogeneous enhancement profile in normal lymph nodes also increase the difficulty of image interpretation 91.

Figure 6.

MRI nodal abnormalities in three patients with prostate cancer. The left panel shows conventional MRI and the middle panel showed MRI obtained 24 hs after the administration of lymphotropic superparamagnetic nanoparticles. The right panel shows corresponding histologic analysis (hematoxylin and eosin). A, a homogeneous decrease in signal intensity due to the accumulation of lymphotropic superparamagnetic nanoparticles in a normal lymph node in the left iliac region. B, conventional MRI shows high signal intensity in an unenlarged iliac lymph node completely replaced by tumor. The nodal signal intensity remains high with nanoparticles. C, conventional MRI shows high signal intensity in a retroperitoneal node with micrometastases. MRI with lymphotropic superparamagnetic nanoparticles demonstrates two hyperintense within the node, corresponding to 2-mm metastases. (Reprinted and modified with the permission from reference 88)

MR lymphangiography in mice and monkeys has also been performed with T1 contrast agents. Herborn et al. 92 used a blood-pool contrast agent, MS-325 (Gadofosveset) to image regional lymph nodes. MS-325 is albumin-binding Gd-based contrast agent and the protein-binding properties may make this agent large enough to be phagocytosed and lymphotropically cleared. After interstitial injection, lymphatic vessels and tumor-bearing lymph nodes can be detected. The same contrast agent has also been premixed with 10% human serum albumin (HSA) for intradermal injection. Lymphatic drainage was visualized clearly by T1-weighted MRI 93. Kobayashi et al. used different dendrimer-based MRI contrast agents to visualize the anatomy and physiology of deep lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes in mouse models 94-96.

Optical imaging guided surgery has been intensively studied due to its low cost, simplicity, and adaptability. Besides, the limited tissue penetration is less critical because of open field of view during surgery 97-101. For example, NIR fluorescent dyes, such as indocyanine green (ICG), have been investigated for sentinel node navigation during surgery either alone or in combination with nanoformulations 26, 27, 102, 103. New imaging systems which integrate invisible light and color video have also been developed to provide intraoperative guidance using NIR lymphatic mapping agents such as indocyanine green (ICG) diluted in human serum albumin (HSA). The NIR fluorescence detection of SLNs was very promising in a small scale of patients with breast cancer 104. Besides small molecular dyes, various nano-scale sized fluorophores have also been applied for SLN imaging and showed promising results in preclinical models 105-109. Kim et al. 106 demonstrated that injection of only 400 pmol of near-infrared quantum dots (a hydrodynamic diameter of 15-20 nm and emission at 840-860 nm) permits sentinel lymph nodes 1 cm deep to be imaged easily in real time using very low excitation fluence rates (5 mW/cm2). With the combination of NIR dyes and microscopic techniques, in vivo functional lymphatic imaging with high spatial and temporal resolution can be achieved 110.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging (CEUS) using mcirobubbles has been widely used in both preclinical experiments and clinical diagnosis 108, 111-118. In preclinical studies, microbubbles have been shown to accumulate in sentinel lymph nodes but not second-order lymph nodes, probably due to the avidity of the shell material for macrophages 119, 120. In a pilot clinical trial, before surgery, patients with breast cancer received a periareolar intradermal injection of microbubbles, lymphatic channels were visualized immediately by ultrasonography and putative axillary SLNs were identified. The sensitivity of SLN detection in this study was 89% 121. Similar to MRI, differentiation of benign and malignant lymph nodes can be achieved with CEUS because of the different accumulation of microbubbles in normal and metastasized LNs 122. Several limitations of CEUS prevent broad application of this technique in SLN mapping, such as poor spatial resolution, slow migration of the microbubble, inaccessibility to the thorax and deep retroperitoneum, as well as its dependence on operator experience 123. Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is a hybrid biomedical imaging modality to detect the ultrasonic waves generated by pulse laser induced transient thermoelastic expansion within biological tissues 124-127. In combination with different contrast agents including methylene blue, carbon nanotubes, gold nanocages, gold nanorods and gold nanobeacons 128-131, PAI showed potential in improved detection of metastases in preclinical models. However, no clinical application has been reported so far, possibly due to the lack of bedside imaging system. In addition, the still limited signal penetration and challenges in control of surgery field with conductive gel may also be the hindrance.

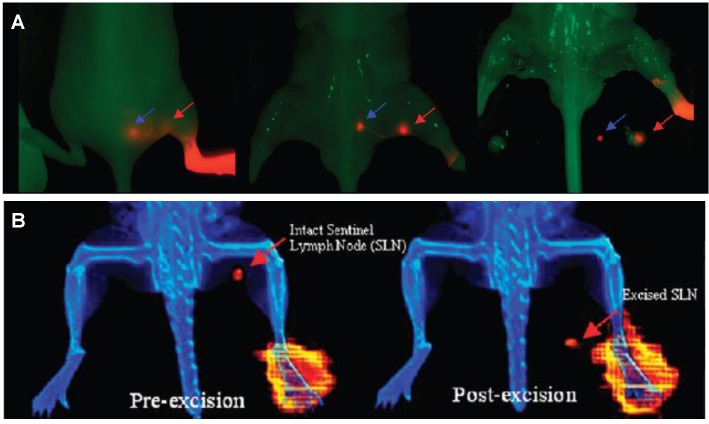

With regard to lymphatic imaging, in order to meet the requirement for both pre-operational evaluation and intra-operational guidance, the combination of multiple imaging techniques is often needed 132. Like the conventional lymphatic mapping with 99mTc-labeled colloids/blue dye, SLNs can be visualized pre-operationally either by SPECT and located with a gamma ray counter and visual contrast of the blue dye during surgery 69, 70. With the development and maturation of hybrid systems including PET/CT, SPECT/CT 34, PET/MRI 133, and bed side optical imaging systems 98, 104, various multifunctional lymphatic imaging probes have been investigated to offer the synergistic advantages, especially those combining radionuclide and fluorescence 134. By taking advantage of lymphatic binding property of tilmanocept, Tsien group 135 conjugated an 18F-labeled NIR fluorophore to the dextran backbone. This dual-labeled compound permits PET or scintigraphic imaging of SLN, and enables NIRF-guided excision for multimodality-guided sentinel node visualization and excision (Figure 7). By mixing 18F-AlF-NEB with Evans blue, our lab also investigated multimodal imaging of LNs. In several animal models, the LNs can be distinguished clearly by the apparent blue color and strong fluorescence signal from EB as well as high intensity PET signal from 18F-AlF-NEB 136. Kobayashi and co-workers 132 synthesized 111In-labeled radionuclide/five-color NIR optical dual-modal imaging probes using a polyamidoamine dendrimer (generation-6 PAMAM dendrimer) with an ethylenediamine core as the platform component. Radionuclide imaging of this dual-modal imaging probe allows increased depth penetration and absolute quantification whereas multi-color NIR optical imaging offers real time spatial resolution and the ability to distinguish multiple lymphatic drainages 132.

Figure 7.

A, nonradioactive NIRF imaging of [19F]Lymphoseek-3. Typical NIRF imaging experiment of a mouse that had been injected with 1 nmol of [19F] Lymphoseek-3 diluted with 10 nmol of unconjugated Lymphoseek. The NIRF signal (colored red) is overlaid onto a bright field image (green) of a mouse. A red arrow indicates clear localization of [19F]Lymphoseek-3 to the sentinel (popliteal) lymph node, while the blue arrow indicates localization to the distal (lumbar) lymph node. B, multimodality imaging of a mouse injected with a 10 μL, 1 nmol, 48.1 μCi dose of 18F-labeled Lymphoseek-3 (0.048 Ci/μmol). The red arrows indicate the location of the sentinel lymph node. (Reprinted and modified with the permission from reference 135).

In a relatively short period, PET/MRI system achieved transition from small PET/MRI prototypes for small-animal studies 137, 138 to clinical arena 139. Consequently, multi-modality imaging agents have been investigated for lymphatic mapping with the hope to detect sites of disease with higher sensitivity and accuracy. For example, a multimodal nanoparticle, 89Zr-ferumoxytol, has been tested in preclinical disease models and the results demonstrated that the particles can be used for high-resolution tomographic studies of lymphatic drainage 140. Our group also developed a mesoporous silica-based triple-modal imaging nanoprobe (MSN-probe) that possesses the long-term imaging ability to track tumor metastatic SLNs. In this system, three imaging tags including NIR dye ZW800, T1 contrast agent Gd3+ and positron emitting radionuclide 64Cu were integrated into MSNs by different conjugation strategies. Due to their high stability and long intracellular retention time, signals from tumor draining SLNs are detectable up to 3 weeks (Figure 8) 105.

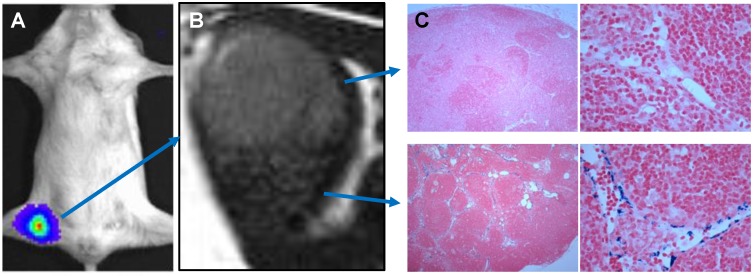

Figure 8.

A, bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of tumor metastasis to tumor draining lymph nodes. B, T2 weighted MRI of a lymph node with tumor metastasis. The heterogeneous signal intensity within the lymph node was distinguished. C, Photomicrograph of histologic specimen was obtained after injection of superparamagnetic iron oxide. The iron-laden cells of the medullary sinusoids were stained blue by the Prussian blue reaction and sharply outline the pink counterstained cortex and medullary cords. Compared with hyperplastic lymphatic tissue, proliferating tumor cells showed much less iron oxide uptake. (Reprinted and modified with the permission from reference 105).

Summary and perspectives

An ideal lymphatic imaging agent should have high signal-to-background ratio for clear SLN detection, be able to differentiate tumor metastasis and provide real-time intraoperative guidance. However, it is very challenging to fulfill all the requirements with a single imaging agent and a single imaging modality. For preclinical studies, the emphasis of imaging is on how to evaluate lymphangiogenesis during pathological processes, especially during the development and metastasis of malignant lesions. Clinically, the focus is still on intraoperative detection of SLN for biopsy and accurate pathological evaluation. This application is mainly for patients with breast cancer and melanoma, but shows potential in other types of cancer including prostate cancer and head and neck cancers. The combination of 99mTc-colloid and vital dyes is still the main stream in clinical practice while other combinations are emerging. With the prevalence of PET and availability of clinically applicable optical imaging systems, more probes with positron emitter and fluorophore labeling are under intensive investigation to provide better pre-operational imaging and intra-operative guidance for SLNB 134.

Various nanoparticles have been investigated for lymphatic imaging, as they have some preferred features including strong signal intensity, tunable size, and modularized modification for multiple modality imaging. For example, based on experience from 99mTc-labeled colloid, the optimal particle size is from 50 to 200 nm since the radioactive colloids are cleared by lymphatic drainage with a speed that is inversely proportional to the particle size after interstitial injection 69. The size of most nanoparticles can be easily tuned to fall in this range. Despite the fact that clinical translation of many nanoparticle formula face formidable obstacles, perceived acute and chronic toxicities, and regulatory hurdles 141, local administration of lymph node mapping will overcome the suboptimal biocompatibility of these NPs.

It is envisioned that PET/optical dual functional imaging probes may be the best combination for clinical SLNB. Pre-operational evaluation could be performed with PET/CT or PET/MRI hybrid systems to provide both LN location and surrounding anatomical reference. While fluorescence optical imaging provides direct visualization of the SLNs and the field of view can be overlaid with bright field images. The localized radioactive signal can substantiate the accuracy of optical imaging. Ex vivo microscopic imaging can be added to provide fast evaluation of tumor micrometastasis in the resected LNs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Swartz MA. The physiology of the lymphatic system. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;50:3–20. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong SY, Hynes RO. Lymphatic or hematogenous dissemination: How does a metastatic tumor cell decide? Cell Cycle. 2006;5:812–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.8.2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Picker LJ, Butcher EC. Physiological and molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte homing. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:561–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karaman S, Detmar M. Mechanisms of lymphatic metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:922–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI71606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tammela T, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis: Molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell. 2010;140:460–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Galimberti V, Viale G, Zurrida S, Bedoni M. et al. Sentinel-node biopsy to avoid axillary dissection in breast cancer with clinically negative lymph-nodes. Lancet. 1997;349:1864–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis GL. Sensitivity of frozen section examination of pelvic lymph nodes for metastatic prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:661–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950815)76:4<661::aid-cncr2820760419>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torabi M, Aquino SL, Harisinghani MG. Current concepts in lymph node imaging. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1509–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qian CN, Berghuis B, Tsarfaty G, Bruch M, Kort EJ, Ditlev J. et al. Preparing the "soil": the primary tumor induces vasculature reorganization in the sentinel lymph node before the arrival of metastatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10365–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eiber M, Beer AJ, Holzapfel K, Tauber R, Ganter C, Weirich G. et al. Preliminary results for characterization of pelvic lymph nodes in patients with prostate cancer by diffusion-weighted MR-imaging. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:15–23. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181bbdc2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiguert R, Gheiler EL, Tefilli MV, Oskanian P, Banerjee M, Grignon DJ. et al. Lymph node size does not correlate with the presence of prostate cancer metastasis. Urology. 1999;53:367–71. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00518-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang F, Niu G, Lu G, Chen X. Preclinical lymphatic imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13:599–612. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0421-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma W, Jia J, Wang S, Bai W, Yi J, Bai M. et al. The prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT for hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) Theranostics. 2014;4:736–44. doi: 10.7150/thno.8725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorensen J. How does the patient benefit from clinical PET? Theranostics. 2012;2:427–36. doi: 10.7150/thno.3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delpassand ES, Samarghandi A, Mourtada JS, Zamanian S, Espenan GD, Sharif R. et al. Long-term survival, toxicity profile, and role of F-18 FDG PET/CT scan in patients with progressive neuroendocrine tumors following peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with high activity In-111 Pentetreotide. Theranostics. 2012;2:472–80. doi: 10.7150/thno.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gambhir SS, Czernin J, Schwimmer J, Silverman DH, Coleman RE, Phelps ME. A tabulated summary of the FDG PET literature. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1S–93S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorek DL, Riedl CC, Grimm J. Clinical Cerenkov luminescence imaging of 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:95–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.127266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conti PS, Lilien DL, Hawley K, Keppler J, Grafton ST, Bading JR. PET and [18F]-FDG in oncology: a clinical update. Nucl Med Biol. 1996;23:717–35. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(96)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hara T, Kosaka N, Kishi H. PET imaging of prostate cancer using carbon-11-choline. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:990–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jadvar H. Can choline PET tackle the challenge of imaging prostate cancer? Theranostics. 2012;2:331–2. doi: 10.7150/thno.4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarzenbock S, Souvatzoglou M, Krause BJ. Choline PET and PET/CT in primary diagnosis and staging of prostate cancer. Theranostics. 2012;2:318–30. doi: 10.7150/thno.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picchio M, Castellucci P. Clinical indications of 11C-choline PET/CT in prostate cancer patients with biochemical relapse. Theranostics. 2012;2:313–7. doi: 10.7150/thno.4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jong IJ, Pruim J, Elsinga PH, Vaalburg W, Mensink HJ. Preoperative staging of pelvic lymph nodes in prostate cancer by 11C-choline PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitajima K, Murphy RC, Nathan MA, Froemming AT, Hagen CE, Takahashi N. et al. Detection of recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: comparison of 11C-choline PET/CT with pelvic multiparametric MR imaging with endorectal coil. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:223–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.123018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fricke E, Machtens S, Hofmann M, van den Hoff J, Bergh S, Brunkhorst T. et al. Positron emission tomography with 11C-acetate and 18F-FDG in prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:607–11. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-1104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannweiler S, Amersdorfer P, Trajanoski S, Terrett JA, King D, Mehes G. Heterogeneity of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) expression in prostate carcinoma with distant metastasis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:167–72. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afshar-Oromieh A, Zechmann CM, Malcher A, Eder M, Eisenhut M, Linhart HG. et al. Comparison of PET imaging with a 68Ga-labelled PSMA ligand and 18F-choline-based PET/CT for the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2525-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baeuerle PA, Gires O. EpCAM (CD326) finding its role in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:417–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeon S, Hong W, Lee ES, Cho Y. High-purity isolation and recovery of circulating tumor cells using conducting polymer-deposited microfluidic device. Theranostics. 2014;4:1123–32. doi: 10.7150/thno.9627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benko G, Spajic B, Kruslin B, Tomas D. Impact of the EpCAM expression on biochemical recurrence-free survival in clinically localized prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:468–74. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall MA, Pinkston KL, Wilganowski N, Robinson H, Ghosh P, Azhdarinia A. et al. Comparison of mAbs targeting epithelial cell adhesion molecule for the detection of prostate cancer lymph node metastases with multimodal contrast agents: quantitative small-animal PET/CT and NIRF. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1427–37. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.106302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang M, Gao H, Yan Y, Sun X, Chen K, Quan Q. et al. PET imaging of early response to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor ZD4190. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2011;38:1237–47. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1742-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brooks PC, Montgomery AM, Rosenfeld M, Reisfeld RA, Hu T, Klier G. et al. Integrin αvβ3 antagonists promote tumor regression by inducing apoptosis of angiogenic blood vessels. Cell. 1994;79:1157–64. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai W, Chen X. Multimodality molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(Suppl 2):113S–28S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Backer MV, Backer JM. Imaging key biomarkers of tumor angiogenesis. Theranostics. 2012;2:502–15. doi: 10.7150/thno.3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niu G, Chen X. Why integrin as a primary target for imaging and therapy. Theranostics. 2011;1:30–47. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noiri E, Goligorsky MS, Wang GJ, Wang J, Cabahug CJ, Sharma S. et al. Biodistribution and clearance of 99mTc-labeled Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide in rats with ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:2682–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7122682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmadi M, Sancey L, Briat A, Riou L, Boturyn D, Dumy P. et al. Chemical and biological evaluations of an 111In-labeled RGD-peptide targeting integrin αvβ3 in a preclinical tumor model. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2008;23:691–700. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2008.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi J, Fan D, Dong C, Liu H, Jia B, Zhao H. et al. Anti-tumor effect of integrin targeted 177Lu-3PRGD2 and combined therapy with Endostar. Theranostics. 2014;4:256–66. doi: 10.7150/thno.7781. doi:10.7150/thno.7781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ji S, Zheng Y, Shao G, Zhou Y, Liu S. Integrin αvβ3-targeted radiotracer 99mTc-3P-RGD2 useful for noninvasive monitoring of breast tumor response to antiangiogenic linifanib therapy but not anti-integrin αvβ3 RGD2 therapy. Theranostics. 2013;3:816–30. doi: 10.7150/thno.6989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haubner R, Maschauer S, Prante O. PET radiopharmaceuticals for imaging integrin expression: Tracers in clinical studies and recent developments. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:871609. doi: 10.1155/2014/871609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beer AJ, Niemeyer M, Carlsen J, Sarbia M, Nahrig J, Watzlowik P. et al. Patterns of αvβ3 expression in primary and metastatic human breast cancer as shown by 18F-Galacto-RGD PET. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:255–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu Z, Miao W, Li Q, Dai H, Ma Q, Wang F. et al. 99mTc-3PRGD2 for integrin receptor imaging of lung cancer: A multicenter study. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:716–22. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.098988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Willmann JK, van Bruggen N, Dinkelborg LM, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:591–607. doi: 10.1038/nrd2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Veit P, Ruehm S, Kuehl H, Stergar H, Mueller S, Bockisch A. et al. Lymph node staging with dual-modality PET/CT: enhancing the diagnostic accuracy in oncology. Eur J Radiol. 2006;58:383–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Antoch G, Stattaus J, Nemat AT, Marnitz S, Beyer T, Kuehl H. et al. Non-small cell lung cancer: dual-modality PET/CT in preoperative staging. Radiology. 2003;229:526–33. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2292021598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lardinois D, Weder W, Hany TF, Kamel EM, Korom S, Seifert B. et al. Staging of non-small-cell lung cancer with integrated positron-emission tomography and computed tomography. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2500–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Platzek I, Beuthien-Baumann B, Ordemann R, Maus J, Schramm G, Kitzler HH. et al. FDG PET/MR for the assessment of lymph node involvement in lymphoma: initial results and role of diffusion-weighted MR. Acad Radiol. 2014;21:1314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Platzek I, Beuthien-Baumann B, Schneider M, Gudziol V, Kitzler HH, Maus J. et al. FDG PET/MR for lymph node staging in head and neck cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83:1163–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harrell MI, Iritani BM, Ruddell A. Tumor-induced sentinel lymph node lymphangiogenesis and increased lymph flow precede melanoma metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:774–86. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ji RC. Lymph node lymphangiogenesis: a new concept for modulating tumor metastasis and inflammatory process. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24:377–84. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banerji S, Ni J, Wang SX, Clasper S, Su J, Tammi R. et al. LYVE-1, a new homologue of the CD44 glycoprotein, is a lymph-specific receptor for hyaluronan. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:789–801. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Breiteneder-Geleff S, Soleiman A, Horvat R, Amann G, Kowalski H, Kerjaschki D. [Podoplanin--a specific marker for lymphatic endothelium expressed in angiosarcoma] Verh Dtsch Ges Pathol. 1999;83:270–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laakkonen P, Porkka K, Hoffman JA, Ruoslahti E. A tumor-homing peptide with a targeting specificity related to lymphatic vessels. Nat Med. 2002;8:751–5. doi: 10.1038/nm720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kishimoto TK, Jutila MA, Butcher EC. Identification of a human peripheral lymph node homing receptor: a rapidly down-regulated adhesion molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:2244–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Licha K, Debus N, Emig-Vollmer S, Hofmann B, Hasbach M, Stibenz D. et al. Optical molecular imaging of lymph nodes using a targeted vascular contrast agent. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:41205. doi: 10.1117/1.2007967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hauff P, Reinhardt M, Briel A, Debus N, Schirner M. Molecular targeting of lymph nodes with L-selectin ligand-specific US contrast agent: A feasibility study in mice and dogs. Radiology. 2004;231:667–73. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2313030425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jackson DG, Prevo R, Clasper S, Banerji S. LYVE-1, the lymphatic system and tumor lymphangiogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:317–21. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01936-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mumprecht V, Honer M, Vigl B, Proulx ST, Trachsel E, Kaspar M. et al. In vivo imaging of inflammation- and tumor-induced lymph node lymphangiogenesis by immuno-positron emission tomography. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8842–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laakkonen P, Zhang L, Ruoslahti E. Peptide targeting of tumor lymph vessels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:37–43. doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laakkonen P, Akerman ME, Biliran H, Yang M, Ferrer F, Karpanen T. et al. Antitumor activity of a homing peptide that targets tumor lymphatics and tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9381–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403317101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang F, Niu G, Lin X, Jacobson O, Ma Y, Eden HS. et al. Imaging tumor-induced sentinel lymph node lymphangiogenesis with LyP-1 peptide. Amino Acids. 2012;42:2343–51. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0976-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jaffer FA, Weissleder R. Molecular imaging in the clinical arena. JAMA. 2005;293:855–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharma R, Wendt JA, Rasmussen JC, Adams KE, Marshall MV, Sevick-Muraca EM. New horizons for imaging lymphatic function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:13–36. doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winnard PT Jr, Pathak AP, Dhara S, Cho SY, Raman V, Pomper MG. Molecular imaging of metastatic potential. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(Suppl 2):96S–112S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baluk P, Tammela T, Ator E, Lyubynska N, Achen MG, Hicklin DJ. et al. Pathogenesis of persistent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in chronic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:247–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Newman EA, Newman LA. Lymphatic mapping techniques and sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:353–64. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.01.013. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tausch C, Baege A, Rageth C. Mapping lymph nodes in cancer management - role of 99mTc-tilmanocept injection. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1151–8. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S50394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mariani G, Moresco L, Viale G, Villa G, Bagnasco M, Canavese G. et al. Radioguided sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer surgery. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1198–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mariani G, Gipponi M, Moresco L, Villa G, Bartolomei M, Mazzarol G. et al. Radioguided sentinel lymph node biopsy in malignant cutaneous melanoma. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:811–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsopelas C, Sutton R. Why certain dyes are useful for localizing the sentinel lymph node. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1377–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brouwer OR, van den Berg NS, Matheron HM, van der Poel HG, van Rhijn BW, Bex A. et al. A hybrid radioactive and fluorescent tracer for sentinel node biopsy in penile carcinoma as a potential replacement for blue dye. Eur Urol. 2014;65:600–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ballou B, Ernst LA, Andreko S, Harper T, Fitzpatrick JA, Waggoner AS. et al. Sentinel lymph node imaging using quantum dots in mouse tumor models. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:389–96. doi: 10.1021/bc060261j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Sato N, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. In vivo real-time, multicolor, quantum dot lymphatic imaging. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2818–22. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsopelas C, Bevington E, Kollias J, Shibli S, Farshid G, Coventry B. et al. 99mTc-Evans blue dye for mapping contiguous lymph node sequences and discriminating the sentinel lymph node in an ovine model. Annals of surgical oncology. 2006;13:692–700. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wallace AM, Hoh CK, Vera DR, Darrah DD, Schulteis G. Lymphoseek: a molecular radiopharmaceutical for sentinel node detection. Annals of surgical oncology. 2003;10:531–8. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leong SP, Kim J, Ross M, Faries M, Scoggins CR, Metz WL. et al. A phase 2 study of 99mTc-tilmanocept in the detection of sentinel lymph nodes in melanoma and breast cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2011;18:961–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brouwer OR, Buckle T, Vermeeren L, Klop WM, Balm AJ, van der Poel HG. et al. Comparing the hybrid fluorescent-radioactive tracer indocyanine green-99mTc-nanocolloid with 99mTc-nanocolloid for sentinel node identification: a validation study using lymphoscintigraphy and SPECT/CT. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1034–40. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.103127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thorek DL, Abou DS, Beattie BJ, Bartlett RM, Huang R, Zanzonico PB. et al. Positron lymphography: multimodal, high-resolution, dynamic mapping and resection of lymph nodes after intradermal injection of 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1438–45. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.104349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Niu G, Lang L, Kiesewetter DO, Ma Y, Sun Z, Guo N. et al. In Vivo Labeling of Serum Albumin for PET. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1150–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.139642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhen Z, Tang W, Chuang YJ, Todd T, Zhang W, Lin X. et al. Tumor vasculature targeted photodynamic therapy for enhanced delivery of nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2014;8:6004–13. doi: 10.1021/nn501134q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Feldman AS, McDougal WS, Harisinghani MG. The potential of nanoparticle-enhanced imaging. Urol Oncol. 2008;26:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saokar A, Braschi M, Harisinghani MG. Lymphotrophic nanoparticle enhanced MR imaging (LNMRI) for lymph node imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:660–7. doi: 10.1007/s00261-006-9006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang F, Huang X, Qian C, Zhu L, Hida N, Niu G. et al. Synergistic enhancement of iron oxide nanoparticle and gadolinium for dual-contrast MRI. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:886–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang F, Zhu L, Huang X, Niu G, Chen X. Differentiation of reactive and tumor metastatic lymph nodes with diffusion-weighted and SPIO-enhanced MRI. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013;15:40–7. doi: 10.1007/s11307-012-0562-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weissleder R, Elizondo G, Wittenberg J, Lee AS, Josephson L, Brady TJ. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide: an intravenous contrast agent for assessing lymph nodes with MR imaging. Radiology. 1990;175:494–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.2.2326475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bellin MF, Beigelman C, Precetti-Morel S. Iron oxide-enhanced MR lymphography: initial experience. Eur J Radiol. 2000;34:257–64. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(00)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, Deserno WM, Tabatabaei S, van de Kaa CH. et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2491–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Harisinghani MG, Dixon WT, Saksena MA, Brachtel E, Blezek DJ, Dhawale PJ. et al. MR lymphangiography: imaging strategies to optimize the imaging of lymph nodes with ferumoxtran-10. Radiographics. 2004;24:867–78. doi: 10.1148/rg.243035190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weissleder R, Stark DD, Engelstad BL, Bacon BR, Compton CC, White DL. et al. Superparamagnetic iron oxide: pharmacokinetics and toxicity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:167–73. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taupitz M, Wagner S, Hamm B, Binder A, Pfefferer D. Interstitial MR lymphography with iron oxide particles: results in tumor-free and VX2 tumor-bearing rabbits. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:193–200. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.1.8517301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Herborn CU, Lauenstein TC, Vogt FM, Lauffer RB, Debatin JF, Ruehm SG. Interstitial MR lymphography with MS-325: characterization of normal and tumor-invaded lymph nodes in a rabbit model. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1567–72. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nakajima T, Turkbey B, Sano K, Sato K, Bernardo M, Hoyt RF. et al. MR lymphangiography with intradermal gadofosveset and human serum albumin in mice and primates. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40:691–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kobayashi H, Kawamoto S, Choyke PL, Sato N, Knopp MV, Star RA. et al. Comparison of dendrimer-based macromolecular contrast agents for dynamic micro-magnetic resonance lymphangiography. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:758–66. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kobayashi H, Kawamoto S, Star RA, Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y, Brechbiel MW. Micro-magnetic resonance lymphangiography in mice using a novel dendrimer-based magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. Cancer Res. 2003;63:271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kobayashi H, Kawamoto S, Sakai Y, Choyke PL, Star RA, Brechbiel MW. et al. Lymphatic drainage imaging of breast cancer in mice by micro-magnetic resonance lymphangiography using a nano-size paramagnetic contrast agent. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:703–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nguyen QT, Tsien RY. Fluorescence-guided surgery with live molecular navigation--a new cutting edge. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:653–62. doi: 10.1038/nrc3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chi C, Du Y, Ye J, Kou D, Qiu J, Wang J. et al. Intraoperative imaging-guided cancer surgery: from current fluorescence molecular imaging methods to future multi-modality imaging technology. Theranostics. 2014;4:1072–84. doi: 10.7150/thno.9899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ashitate Y, Hyun H, Kim SH, Lee JH, Henary M, Frangioni JV. et al. Simultaneous mapping of pan and sentinel lymph nodes for real-time image-guided surgery. Theranostics. 2014;4:693–700. doi: 10.7150/thno.8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Park MH, Hyun H, Ashitate Y, Wada H, Park G, Lee JH. et al. Prototype nerve-specific near-infrared fluorophores. Theranostics. 2014;4:823–33. doi: 10.7150/thno.8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wada H, Hyun H, Vargas C, Gravier J, Park G, Gioux S. et al. Pancreas-targeted NIR fluorophores for dual-channel image-guided abdominal surgery. Theranostics. 2015;5:1–11. doi: 10.7150/thno.10259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hirano A, Kamimura M, Ogura K, Kim N, Hattori A, Setoguchi Y. et al. A comparison of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging plus blue dye and blue dye alone for sentinel node navigation surgery in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4112–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Koo J, Jeon M, Oh Y, Kang HW, Kim J, Kim C. et al. In vivo non-ionizing photoacoustic mapping of sentinel lymph nodes and bladders with ICG-enhanced carbon nanotubes. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57:7853–62. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/23/7853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Troyan SL, Kianzad V, Gibbs-Strauss SL, Gioux S, Matsui A, Oketokoun R. et al. The FLARE intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence imaging system: a first-in-human clinical trial in breast cancer sentinel lymph node mapping. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2943–52. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0594-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Huang X, Zhang F, Lee S, Swierczewska M, Kiesewetter DO, Lang L. et al. Long-term multimodal imaging of tumor draining sentinel lymph nodes using mesoporous silica-based nanoprobes. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4370–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim S, Lim YT, Soltesz EG, De Grand AM, Lee J, Nakayama A. et al. Near-infrared fluorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel lymph node mapping. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:93–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Verbeek FP, Troyan SL, Mieog JS, Liefers GJ, Moffitt LA, Rosenberg M. et al. Near-infrared fluorescence sentinel lymph node mapping in breast cancer: a multicenter experience. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2014;143:333–42. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2802-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dewitte H, Vanderperren K, Haers H, Stock E, Duchateau L, Hesta M. et al. Theranostic mRNA-loaded Microbubbles in the Lymphatics of Dogs: Implications for Drug Delivery. Theranostics. 2015;5:97–109. doi: 10.7150/thno.10298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu L, Luderer M, Yang X, Swain C, Zhang H, Nelson K. et al. Surface passivation of carbon nanoparticles with branched macromolecules influences near infrared bioimaging. Theranostics. 2013;3:677–86. doi: 10.7150/thno.6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Proulx ST, Luciani P, Christiansen A, Karaman S, Blum KS, Rinderknecht M. et al. Use of a PEG-conjugated bright near-infrared dye for functional imaging of rerouting of tumor lymphatic drainage after sentinel lymph node metastasis. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sirsi SR, Borden MA. Advances in ultrasound mediated gene therapy using microbubble contrast agents. Theranostics. 2012;2:1208–22. doi: 10.7150/thno.4306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yoon YI, Kwon YS, Cho HS, Heo SH, Park KS, Park SG. et al. Ultrasound-mediated gene and drug delivery using a microbubble-liposome particle system. Theranostics. 2014;4:1133–44. doi: 10.7150/thno.9945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jian J, Liu C, Gong Y, Su L, Zhang B, Wang Z. et al. India ink incorporated multifunctional phase-transition nanodroplets for photoacoustic/ultrasound dual-modality imaging and photoacoustic effect based tumor therapy. Theranostics. 2014;4:1026–38. doi: 10.7150/thno.9754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fan CH, Lin WH, Ting CY, Chai WY, Yen TC, Liu HL. et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging for the detection of focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening. Theranostics. 2014;4:1014–25. doi: 10.7150/thno.9575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu HL, Fan CH, Ting CY, Yeh CK. Combining microbubbles and ultrasound for drug delivery to brain tumors: current progress and overview. Theranostics. 2014;4:432–44. doi: 10.7150/thno.8074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vlaisavljevich E, Durmaz YY, Maxwell A, Elsayed M, Xu Z. Nanodroplet-mediated histotripsy for image-guided targeted ultrasound cell ablation. Theranostics. 2013;3:851–64. doi: 10.7150/thno.6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sirsi SR, Fung C, Garg S, Tianning MY, Mountford PA, Borden MA. Lung surfactant microbubbles increase lipophilic drug payload for ultrasound-targeted delivery. Theranostics. 2013;3:409–19. doi: 10.7150/thno.5616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Streeter JE, Dayton PA. An in vivo evaluation of the effect of repeated administration and clearance of targeted contrast agents on molecular imaging signal enhancement. Theranostics. 2013;3:93–8. doi: 10.7150/thno.5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lindner JR, Coggins MP, Kaul S, Klibanov AL, Brandenburger GH, Ley K. Microbubble persistence in the microcirculation during ischemia/reperfusion and inflammation is caused by integrin- and complement-mediated adherence to activated leukocytes. Circulation. 2000;101:668–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lurie DM, Seguin B, Schneider PD, Verstraete FJ, Wisner ER. Contrast-assisted ultrasound for sentinel lymph node detection in spontaneously arising canine head and neck tumors. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:415–21. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000201230.29925.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sever A, Jones S, Cox K, Weeks J, Mills P, Jones P. Preoperative localization of sentinel lymph nodes using intradermal microbubbles and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in patients with breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1295–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Goldberg BB, Merton DA, Liu JB, Thakur M, Murphy GF, Needleman L. et al. Sentinel lymph nodes in a swine model with melanoma: contrast-enhanced lymphatic US. Radiology. 2004;230:727–34. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303021440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ravizzini G, Turkbey B, Barrett T, Kobayashi H, Choyke PL. Nanoparticles in sentinel lymph node mapping. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2009;1:610–23. doi: 10.1002/wnan.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang LV, Hu S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science. 2012;335:1458–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1216210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mallidi S, Watanabe K, Timerman D, Schoenfeld D, Hasan T. Prediction of tumor recurrence and therapy monitoring using ultrasound-guided photoacoustic imaging. Theranostics. 2015;5:289–301. doi: 10.7150/thno.10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhang R, Pan D, Cai X, Yang X, Senpan A, Allen JS. et al. alphanubeta3-targeted Copper Nanoparticles Incorporating an Sn 2 Lipase-Labile Fumagillin Prodrug for Photoacoustic Neovascular Imaging and Treatment. Theranostics. 2015;5:124–33. doi: 10.7150/thno.10014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wilson KE, Bachawal SV, Tian L, Willmann JK. Multiparametric spectroscopic photoacoustic imaging of breast cancer development in a transgenic mouse model. Theranostics. 2014;4:1062–71. doi: 10.7150/thno.9922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Song KH, Stein EW, Margenthaler JA, Wang LV. Noninvasive photoacoustic identification of sentinel lymph nodes containing methylene blue in vivo in a rat model. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:054033. doi: 10.1117/1.2976427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.De la Zerda A, Zavaleta C, Keren S, Vaithilingam S, Bodapati S, Liu Z. et al. Carbon nanotubes as photoacoustic molecular imaging agents in living mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:557–62. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kim JW, Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Moon HM, Zharov VP. Golden carbon nanotubes as multimodal photoacoustic and photothermal high-contrast molecular agents. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:688–94. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Pan D, Pramanik M, Senpan A, Ghosh S, Wickline SA, Wang LV. et al. Near infrared photoacoustic detection of sentinel lymph nodes with gold nanobeacons. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4088–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kobayashi H, Koyama Y, Barrett T, Hama Y, Regino CA, Shin IS. et al. Multimodal nanoprobes for radionuclide and five-color near-infrared optical lymphatic imaging. ACS Nano. 2007;1:258–64. doi: 10.1021/nn700062z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Boss A, Bisdas S, Kolb A, Hofmann M, Ernemann U, Claussen CD. et al. Hybrid PET/MRI of intracranial masses: initial experiences and comparison to PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1198–205. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.074773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lutje S, Rijpkema M, Helfrich W, Oyen WJ, Boerman OC. Targeted radionuclide and fluorescence dual-modality imaging of cancer: preclinical advances and clinical translation. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16:747–55. doi: 10.1007/s11307-014-0747-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ting R, Aguilera TA, Crisp JL, Hall DJ, Eckelman WC, Vera DR. et al. Fast 18F labeling of a near-infrared fluorophore enables positron emission tomography and optical imaging of sentinel lymph nodes. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:1811–9. doi: 10.1021/bc1001328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wang Y, Lang L, Huang P, Wang Z, Jacobson O, Kiesewetter DO. et al. In vivo albumin labeling and lymphatic imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:208–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414821112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Catana C, Procissi D, Wu Y, Judenhofer MS, Qi J, Pichler BJ. et al. Simultaneous in vivo positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3705–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711622105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Judenhofer MS, Wehrl HF, Newport DF, Catana C, Siegel SB, Becker M. et al. Simultaneous PET-MRI: A new approach for functional and morphological imaging. Nat Med. 2008;14:459–65. doi: 10.1038/nm1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Partovi S, Kohan A, Rubbert C, Vercher-Conejero JL, Gaeta C, Yuh R. et al. Clinical oncologic applications of PET/MRI: a new horizon. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;4:202–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Thorek DL, Ulmert D, Diop NF, Lupu ME, Doran MG, Huang R. et al. Non-invasive mapping of deep-tissue lymph nodes in live animals using a multimodal PET/MRI nanoparticle. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3097. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sengupta J, Ghosh S, Datta P, Gomes A. Physiologically important metal nanoparticles and their toxicity. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2014;14:990–1006. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.9078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]