Abstract

Following the discovery of pluripotent stem (PS) cells such as embryonic stem (ES) and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, there has been a great hope that injured tissues can be repaired by transplantation of ES/iPS-derived various specific types of cells such as neural stem cells (NSCs). Although PS cells can be induced by ectopic expression of Yamanaka's factors, it is known that several stimuli such as ischemia/hypoxia can increase the stemness of somatic cells via reprogramming. This suggests that endogenous somatic cells acquire stemness during natural regenerative processes following injury. In this study, we describe whether somatic cells are converted into pluripotent stem cells by pathological stimuli without ectopic expression of reprogramming factors based on the findings of ischemia-induced multipotent stem cells in a mouse model of cerebral infarction.

1. Introduction

Reprogramming by ectopic expression of different transcription factors can induce conversion of adult mammalian somatic cells into various types of stem cells (e.g., induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells by c-myc, Klf4, Sox2, and Oct3/4 [1, 2]; neural stem cells (NSCs) by c-myc, Klf4, and Sox2 [3]). However, increasing evidence has shown that reprogramming occurs in various organs during natural regenerative processes following injuries [4, 5]. Thus, it may be ideal if endogenous somatic cells can be converted into pluripotent stem (PS) cells under pathological conditions, thereby contributing to regeneration of damaged tissues.

Brain injuries such as ischemia/hypoxia promote the induction of endogenous NSCs [6]. Although the mechanism of NSC induction remains unknown, increasing evidence has shown that ischemia/hypoxia can increase stemness via reprogramming [7, 8]. In support of this idea, we recently showed that brain somatic cells such as pericytes (PCs) within ischemic regions developed stemness, thereby acquiring NSC activity [9–11]. Brain-derived, ischemia-induced stem cells (iSCs) exhibited several PS cell markers such as c-myc, Klf4, Sox2, and Nanog and also showed their multipotency to differentiate into both neural and nonneural cell lineages, presumably through reprogramming [12]. However, it remains unclear whether iSCs can acquire traits similar to those of embryonic stem (ES) and iPS cells.

Recently, Takahashi et al. discovered that somatic cells such as fibroblast cells can be transformed into PS cells with phenotypes similar to ES cells by exogenous expression of Yamanaka's four factors: c-myc, Klf4, Sox2, and Oct4 [1, 2]. Thus, if endogenous somatic cells can be successfully reprogrammed into PS cells in response to stimuli, they must express Yamanaka's four factors. In this study, we described whether stimulated somatic cells can indeed be converted into ES/iPS-like pluripotent state without ectopic expression of reprogramming factors. We focused on the expression of Yamanaka's four factors in iSCs extracted from poststroke adult mouse brains subjected to cerebral infarction.

2. What Is the Origin of iSCs?

In the adult mammalian brain, it is well known that NSCs are present in specific brain regions such as the subventricular zone and subgranular zone within the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and that ongoing neurogenesis is retained in these two zones [13, 14]. Although precise phenotypes of NSCs remain unclear, various types of glial cell lineages such as radial glia [15], astrocytes in the subventricular zone [16], reactive astrocytes [6], resident glia [17, 18], and oligodendrocyte precursor cells [19] have been considered to be possible sources of NSCs.

NSCs are narrowly defined as stem cells that only give rise to neural cell lineages. However, increasing evidence shows that certain NSCs differentiate into both neural and nonneural lineages [20–22]. Thus, in a broad sense, NSCs are defined as multipotent stem cells that can differentiate into various lineages, including neural cells. Although the precise origin, identity, and subtype of such multipotent NSCs remain unclear, we recently demonstrated the development of injury-induced NSCs (iNSCs) within ischemic areas of poststroke brain, with a model of focal cortical infarction in adult mice. These iNSCs possessed self-renewal capacity, which was confirmed by 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine uptake. The iNSCs formed neurosphere-like cell clusters in vitro and differentiated into electrophysiologically functional neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [23]. In addition, we have shown that iNSCs originate, at least in part, from reactive PCs within ischemic regions [9, 10] and that such PCs extracted from ischemic regions (iPCs) exhibited multipotency [12], consistent with the traits of PCs that have multilineage differentiation potential [24–31]. These findings indicate that, under pathological conditions, iPCs may be the origin of iSCs that give rise to iNSCs [9–12].

3. Are iSCs ES/iPS-Like Stem Cells?

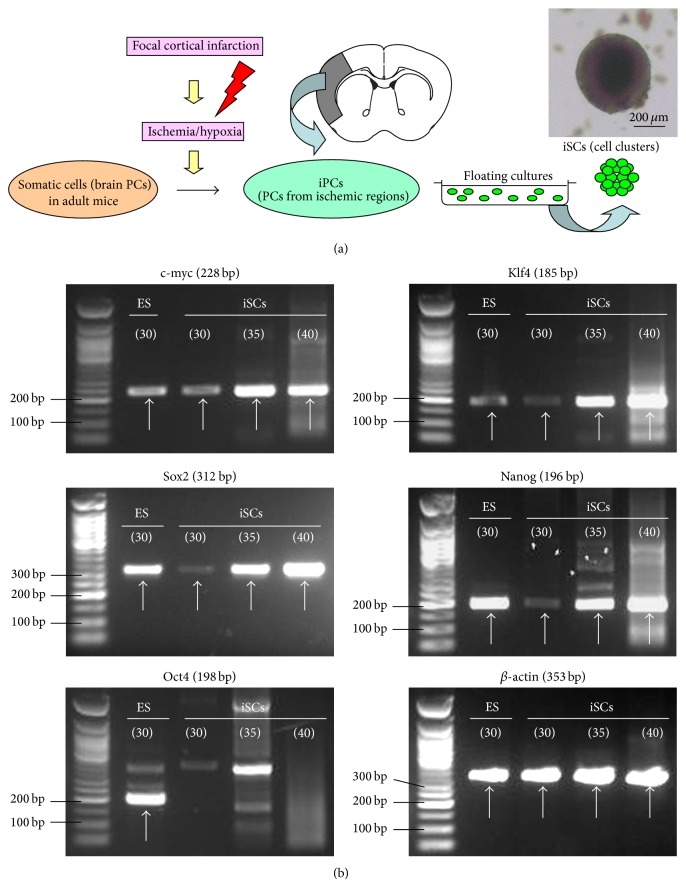

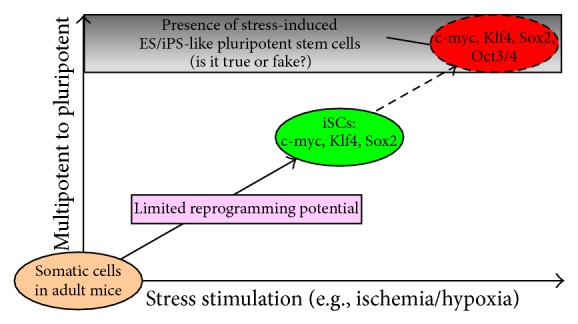

iPC-derived iSCs expressed the NSC marker nestin as well as PC markers such as PDGFRβ, NG2, and αSMA. In addition, iSCs formed cell clusters (Figure 1(a)) and displayed pluripotency markers c-myc, Klf4, and Sox2 of Yamanaka's four factors (Figure 1(b)), as described previously [9, 12], which is consistent with the phenotypes of developing NSCs [32]. Furthermore, iSCs expressed the PS cell marker Nanog, although expression of Nanog as well as Sox2 was weak compared with that of control ES cells. However, our previous study showed that iSCs isolated from adult mouse brain did not express Oct4 by any method, including Western blot [9] and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analyses [12]. In addition, Oct4 was not observed even after > 35 cycles of PCR amplification (Figure 1(b)), which should be able to detect very low levels of Oct4 in tissue-committed stem cells such as very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs) [33]. The evidence that iSCs expressed c-myc, Klf4, and Sox2, but not Oct4, indicates that iSCs have different traits compared with that of PS cells such as ES/iPS cells. This also suggests that somatic cells in adult mouse brain have limited reprogramming potential in response to stimuli, thereby acquiring less stemness compared with that of ES/iPS cells (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

iSCs were isolated from ischemic areas and formed cells clusters (a). iSCs as well as control ES cells expressed c-myc, Klf4, Sox2, and Nanog. However, Oct4 was not observed even after > 35 cycles of PCR amplification. The cycle number of PCR amplification is shown in the circles (b).

Figure 2.

Evidence that iSCs lacking Oct4 have different traits compared with those of ES/iPS cells, suggesting that somatic cells in adult mouse brains have limited reprogramming potential in response to stimuli.

One critical question is whether PCs are indeed somatic cells because other groups have suggested that PCs originally possess stemness [24]. However, it is possible that such “naïve” PCs acquire stemness during in vitro treatment (e.g., repeated passages and chemical stimulation) because our studies showed that PCs in normal (nonischemic) areas rarely express Yamanaka's factors by immunohistochemistry and Western blot [9, 12]. Furthermore, we have never obtained PCs with stemness from nonischemic areas, which strongly suggests that under normal conditions, PCs in adult mice are initially somatic cells rather than tissue-committed stem cells. Even if PCs originally have a certain degree of stemness, our results still show that it is difficult for PCs in adult mouse brain to become ES/iPS-like stem cells by stimuli alone.

4. Why Do iSCs Express Reprogramming Factors following Ischemic Stroke?

iSCs could be easily isolated from ischemic areas but not nonischemic areas [9, 10, 12, 34, 35], showing that ischemia is essential for induction of iSCs. Ischemia is reported to activate the reprogramming factor c-myc following stroke [36]. Consistent with that study, using a mouse model of stroke, we have shown that c-myc+ cells were present within ischemic regions, including iSCs; however, they were rarely observed within nonischemic regions [12]. In addition, we showed that the reprogramming factors such as Klf4 and Sox2 were also expressed in iSCs within ischemic regions, whereas they were rarely expressed within nonischemic regions [12]. Furthermore, our study using commercially available primary human pericytes (hPCs) showed that under oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) conditions, which mimic ischemia/hypoxia in vivo [37], hPCs rapidly increased Klf4 expression [12]. This suggests that OGD is a positive factor for inducing Klf4 following ischemic stroke in vivo. However, OGD itself did not affect expression of c-myc in hPCs, although ischemic stroke increased expression of c-myc in vivo. In addition, we found that Sox2 expression by OGD treatment was not as remarkable as Klf4 expression, although Sox2 was activated in iSCs following ischemic stroke [12].

These findings indicate that OGD itself cannot completely mimic ischemic events in vivo and that factors other than OGD are also involved in the activation of reprogramming factors in iSCs following ischemic stroke. In support of this idea, we found that environmental factors such as leukemia inhibitory factor [38] and basic fibroblast growth factor [39] that are secreted from stimulated endothelial cells surrounding PCs also function as positive factors for activation of Sox2 [12]. These findings indicate that in vivo ischemia is a very complex event, and likely multiple factors, including OGD, are involved in the activation of reprogramming factors in iSCs following ischemic stroke. Additional studies are required to clarify which factors/signal pathways are critical to induction of iSCs.

5. What Other Previously Reported Stem Cells Express Oct4 Other than ES/iPS Cells?

Although we have never detected Oct4 expression in iSCs, previous reports by other groups have shown Oct4 expression in several types of stem cells other than ES/iPS cells, such as VSELs [33, 40–43] and multilineage-differentiating stress-enduring cells (muse cells) [44, 45]. Ratajczak and colleagues reported that VSELs are a population of developmentally early and small stem cells residing in adult tissues of both mice and humans [40, 42]. VSELs, defined by Lin−Sca-1+CD45− markers, were reported to have phenotypes of PS cells. VSELs express PS cell markers such as stage-specific embryonic antigen (SSEA)-1, SSEA-4, Nanog, and even Oct4 [42, 46], although Oct4 expression in VSELs was very low compared with that of ES cells [33]. The population of quiescent VSELs expands in response to stimuli [43]. Until now, VSELs were reported to be isolated from various tissues, including bone marrow, testis, and ovary [33, 40, 41]. However, as far as we know, there has been no report of VSELs being obtained from brain. Thus, it is possible that Oct4 expression in stem cells is originally different among organs (e.g., between brains and bone marrow). However, recent studies by several independent researchers cast doubt on the presence of VSELs because they could not find Oct4-expressing PS cells in reported VSEL populations [47–49]. Therefore, the exact characteristics of VSELs should be clarified in further studies.

Muse cells are PS cells which belong to mesenchymal lineages and can be isolated from various tissues (e.g., bone marrows and skin) as SSEA-3/CD105 double-positive cells [44, 45]. In addition, muse cells are reported to express various PS cell markers, including Sox2, Nanog, and Oct4. However, Oct4 expression of muse cells was quite low compared with that of ES cells, and muse cells did not contribute to formation of teratoma-like tumorigenesis. Thus, it seems apparent that muse cells do not have the pluripotency to the degree observed in ES/iPS cells. Until now, muse cells expressing Oct4 can be successfully isolated from humans but not from other species. This also suggests that stemness is originally different among species (e.g., between mice and humans), although their precise traits remain unclear.

There have been many reports in which authors described that various types of stem cells such as mesenchymal stem cells [50, 51], adipose-derived stromal cells [52], and neural crest-derived stem cells [53–55] expressed Oct4. However, Bhartiya implied that some studies may have misinterpreted Oct4 expression [33]. Takeda et al. showed that Oct4 has two major isoforms, Oct4A and Oct4B, and only Oct4A is related to pluripotency, whereas Oct4B has no biological function [56]. Further, Warthemann et al. pointed out that it is possible that a false-positive for Oct4A expression may lead to misinterpretation [57]. Thus, stem cell biologists should carefully investigate Oct4 expression using appropriate positive controls such as ES/iPS cells because Oct4 is a key factor when estimating the state of pluripotency [1, 2, 58].

6. Conclusion

Herein, we discussed in detail whether stimulated somatic cells can acquire pluripotency. Our studies regarding iSCs showed they expressed c-myc, Klf4, and Sox2, but not Oct4, suggesting that even with severe stimuli, such as ischemia/hypoxia, which promote reprogramming, it is not easy to reprogram adult somatic cells into an ES/iPS-like state. Although iSCs lacked Oct4, pluripotency of iSCs should be carefully investigated because they certainly express various pluripotent markers such as c-myc, Klf4, Sox2, and Nanog, as we previously demonstrated [9, 12]. We need further examination regarding teratoma formation capacity and germline transmission ability. We also understand that further studies are required using younger mice (e.g., neonatal mice), various organs (e.g., bone marrow, liver, and lung), various stimuli (e.g., sheer stress), and/or other species (e.g., rat and human). We hope that stem cell biologists would provide convincing answers for these fundamental questions in future investigations.

Abbreviations

- ES cells:

Embryonic stem cells

- iNSCs:

Ischemia-induced neural stem cells

- iPCs:

Pericytes extracted from ischemic regions

- iPS cells:

Induced pluripotent stem cells

- iSCs:

Ischemia-induced stem cells

- NSCs:

Neural stem cells

- PCs:

Pericytes

- PS cells:

Pluripotent stem cells

- hPCs:

Human pericytes

- VSELs:

Very small embryonic-like stem cells

- SSEA:

Stage-specific embryonic antigen

- RT-PCR:

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- OGD:

Oxygen-glucose deprivation.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. Induction of of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thier M., Wörsdörfer P., Lakes Y. B., et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts into stably expandable neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(4):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanger K., Zong Y., Maggs L. R., et al. Robust cellular reprogramming occurs spontaneously during liver regeneration. Genes and Development. 2013;27(7):719–724. doi: 10.1101/gad.207803.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luz-Madrigal A., Grajales-Esquivel E., McCorkle A., et al. Reprogramming of the chick retinal pigmented epithelium after retinal injury. BMC Biology. 2014;12, article 28 doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimada I. S., Peterson B. M., Spees J. L. Isolation of locally derived stem/progenitor cells from the peri-infarct area that do not migrate from the lateral ventricle after cortical stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(9):e552–e560. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohyeldin A., Garzón-Muvdi T., Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(2):150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshida Y., Takahashi K., Okita K., Ichisaka T., Yamanaka S. Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5(3):237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakagomi T., Molnár Z., Nakano-Doi A., et al. Ischemia-induced neural stem/progenitor cells in the pia mater following cortical infarction. Stem Cells and Development. 2011;20(12):2037–2051. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagomi T., Molnár Z., Taguchi A., et al. Leptomeningeal-derived doublecortin-expressing cells in poststroke brain. Stem Cells and Development. 2012;21(13):2350–2354. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagomi T., Nakano-Doi A., Matsuyama T. Leptomeninges: a novel stem cell niche harboring ischemia-induced neural progenitors. Histology and Histopathology. 2015;30:391–399. doi: 10.14670/HH-30.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagomi T., Kubo S., Nakano-Doi A., et al. Brain vascular pericytes following ischemia have multipotential stem cell activity to differntiate into neural and vascular lineage cells. Stem Cells. 2015 doi: 10.1002/stem.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez-Buylla A., García-Verdugo J. M. Neurogenesis in adult subventricular zone. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(3):629–634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00629.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn H. G., Dickinson-Anson H., Gage F. H. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(6):2027–2033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02027.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kriegstein A., Alvarez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32:149–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doetsch F., García-Verdugo J. M., Alvarez-Buylla A. Regeneration of a germinal layer in the adult mammalian brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(20):11619–11624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belachew S., Chittajallu R., Aguirre A. A., et al. Postnatal NG2 proteoglycan-expressing progenitor cells are intrinsically multipotent and generate functional neurons. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;161(1):169–186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson W. D., Young K. M., Tripathi R. B., McKenzie I. NG2-glia as multipotent neural stem cells: fact or fantasy? Neuron. 2011;70(4):661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kondo T., Raff M. Oligodendrocyte precursor cells reprogrammed to become multipotential CNS stem cells. Science. 2000;289(5485):1754–1757. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ii M., Nishimura H., Sekiguchi H., et al. Concurrent vasculogenesis and neurogenesis from adult neural stem cells. Circulation Research. 2009;105(9):860–868. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oishi K., Ito-Dufros Y. Angiogenic potential of CD44+ CD90+ multipotent CNS stem cells in vitro. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;349(3):1065–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wurmser A. E., Nakashima K., Summers R. G., et al. Cell fusion-independent differentiation of neural stem cells to the endothelial lineage. Nature. 2004;430(6997):350–356. doi: 10.1038/nature02604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagomi T., Taguchi A., Fujimori Y., et al. Isolation and characterization of neural stem/progenitor cells from post-stroke cerebral cortex in mice. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(9):1842–1852. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dore-Duffy P., Katychev A., Wang X., van Buren E. CNS microvascular pericytes exhibit multipotential stem cell activity. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2006;26(5):613–624. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birbrair A., Zhang T., Wang Z.-M., et al. Skeletal muscle pericyte subtypes differ in their differentiation potential. Stem Cell Research. 2013;10(1):67–84. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birbrair A., Zhang T., Wang Z. M., Messi M. L., Mintz A., Delbono O. Pericytes: multitasking cells in the regeneration of injured, diseased, and aged skeletal muscle. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2014;6, article 245 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birbrair A., Zhang T., Wang Z. M., et al. Type-2 pericytes participate in normal and tumoral angiogenesis. The American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology. 2014;307:C25–C38. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00084.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karow M., Sánchez R., Schichor C., et al. Reprogramming of pericyte-derived cells of the adult human brain into induced neuronal cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(4):471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doherty M. J., Ashton B. A., Walsh S., Beresford J. N., Grant M. E., Canfield A. E. Vascular pericytes express osteogenic potential in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1998;13(5):828–838. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dar A., Domev H., Ben-Yosef O., et al. Multipotent vasculogenic pericytes from human pluripotent stem cells promote recovery of murine ischemic limb. Circulation. 2012;125(1):87–99. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.048264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrington-Rock C., Crofts N. J., Doherty M. J., Ashton B. A., Griffin-Jones C., Canfield A. E. Chondrogenic and adipogenic potential of microvascular pericytes. Circulation. 2004;110(15):2226–2232. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000144457.55518.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J. B., Zaehres H., Wu G., et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature. 2008;454(7204):646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature07061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhartiya D. Are mesenchymal cells indeed pluripotent stem cells or just stromal cells? OCT-4 and VSELs biology has led to better understanding. Stem Cells International. 2013;2013:6. doi: 10.1155/2013/547501.547501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagomi N., Nakagomi T., Kubo S., et al. Endothelial cells support survival, proliferation, and neuronal differentiation of transplanted adult ischemia-induced neural stem/progenitor cells after cerebral infarction. Stem Cells. 2009;27(9):2185–2195. doi: 10.1002/stem.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakano-Doi A., Nakagomi T., Fujikawa M., et al. Bone marrow mononuclear cells promote proliferation of endogenous neural stem cells through vascular niches after cerebral infarction. Stem Cells. 2010;28(7):1292–1302. doi: 10.1002/stem.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakagomi T., Asai A., Kanemitsu H., et al. Up-regulation of c-myc gene expression following focal ischemia in the rat brain. Neurological Research. 1996;18(6):559–563. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1996.11740470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurtado O., Moro M. A., Cárdenas A., et al. Neuroprotection afforded by prior citicoline administration in experimental brain ischemia: effects on glutamate transport. Neurobiology of Disease. 2005;18(2):336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubota Y., Hirashima M., Kishi K., Stewart C. L., Suda T. Leukemia inhibitory factor regulates microvessel density by modulating oxygen-dependent VEGF expression in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(7):2393–2403. doi: 10.1172/jc134882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo J., Qiao F., Yin X. Hypoxia induces FGF2 production by vascular endothelial cells and alters MMP9 and TIMP1 expression in extravillous trophoblasts and their invasiveness in a cocultured model. Journal of Reproduction and Development. 2011;57(1):84–91. doi: 10.1262/jrd.10-008k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratajczak M. Z., Shin D.-M., Liu R., et al. Very Small Embryonic/Epiblast-Like stem cells (VSELs) and their potential role in aging and organ rejuvenation—an update and comparison to other primitive small stem cells isolated from adult tissues. Aging. 2012;4(4):235–246. doi: 10.18632/aging.100449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parte S., Bhartiya D., Telang J., et al. Detection, characterization, and spontaneous differentiation in vitro of very small embryonic-like putative stem cells in adult mammalian ovary. Stem Cells and Development. 2011;20(8):1451–1464. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Kucia M., Reca R., Campbell F. R., et al. A population of very small embryonic-like (VSEL) CXCR4+SSEA-1+Oct-4+ stem cells identified in adult bone marrow. Leukemia. 2006;20:857–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grymula K., Tarnowski M., Piotrowska K., et al. Evidence that the population of quiescent bone marrow-residing very small embryonic/epiblast-like stem cells (VSELs) expands in response to neurotoxic treatment. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2014;18(9):1797–1806. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuroda Y., Wakao S., Kitada M., Murakami T., Nojima M., Dezawa M. Isolation, culture and evaluation of multilineage-differentiating stress-enduring (Muse) cells. Nature Protocols. 2013;8(7):1391–1415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuroda Y., Kitada M., Wakao S., et al. Unique multipotent cells in adult human mesenchymal cell populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(19):8639–8643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911647107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kucia M., Halasa M., Wysoczynski M., et al. Morphological and molecular characterization of novel population of CXCR4+ SSEA-4+ Oct-4+ very small embryonic-like cells purified from human cord blood - Preliminary report. Leukemia. 2007;21(2):297–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szade K., Bukowska-Strakova K., Nowak W. N., Jozkowicz A., Dulak J. Comment on: the proper criteria for identification and sorting of very small embryonic-like stem cells, and some nomenclature issues. Stem Cells and Development. 2014;23(7):714–716. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szade K., Bukowska-Strakova K., Nowak W. N., et al. Murine bone marrow Lin−Sca-1+CD45− very small embryonic-like (VSEL) cells are heterogeneous population lacking Oct-4A expression. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063329.e63329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyanishi M., Mori Y., Seita J., et al. Do pluripotent stem cells exist in adult mice as very small embryonic stem cells? Stem Cell Reports. 2013;1(2):198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poloni A., Maurizi G., Leoni P., et al. Human dedifferentiated adipocytes show similar properties to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30(5):965–974. doi: 10.1002/stem.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roche S., Richard M.-J., Favrot M.-C. Oct-4, Rex-1, and Gata-4 expression in human MSC increase the differentiation efficiency but not hTERT expression. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2007;101(2):271–280. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao Q., Zhao L., Song Z., Yang G. Expression pattern of embryonic stem cell markers in DFAT cells and ADSCs. Molecular Biology Reports. 2012;39(5):5791–5804. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hauser S., Widera D., Qunneis F., et al. Isolation of novel multipotent neural crest-derived stem cells from adult human inferior turbinate. Stem Cells and Development. 2012;21(5):742–756. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pelaez D., Huang C.-Y. C., Cheung H. S. Isolation of pluripotent neural crest-derived stem cells from adult human tissues by connexin-43 enrichment. Stem Cells and Development. 2013;22(21):2906–2914. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Widera D., Zander C., Heidbreder M., et al. Adult palatum as a novel source of neural crest-related stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(8):1899–1910. doi: 10.1002/stem.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takeda J., Seino S., Bell G. I. Human Oct3 gene family: cDNA sequences, alternative splicing, gene organization, chromosomal location, and expression at low levels in adult tissues. Nucleic Acids Research. 1992;20(17):4613–4620. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warthemann R., Eildermann K., Debowski K., Behr R. False-positive antibody signals for the pluripotency factor OCT4A (POU5F1) in testis-derived cells may lead to erroneous data and misinterpretations. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2012;18(12):605–612. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gas032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hay D. C., Sutherland L., Clark J., Burdon T. Oct-4 knockdown induces similar patterns of endoderm and trophoblast differentiation markers in human and mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22(2):225–235. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-2-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]