Abstract

Fibromatous soft tissue lesions, namely desmoid-type fibromatosis and Gardner fibroma, may occur sporadically or as a result of inherited predisposition (as part of familial adenomatous polyposis, FAP). Whereas desmoid-type fibromatosis often present β-catenin overexpression (by activating CTNNB1 somatic variants or APC biallelic inactivation), the pathogenetic mechanisms in Gardner fibroma are unknown. We characterized in detail Gardner fibromas diagnosed in two infants to evaluate their role as sentinel lesions of previously unrecognized FAP. In the first infant we found a 5q deletion including APC in the tumor and the novel APC variant c.4687dup in constitutional DNA. In the second infant we found the c.5826_5829del and c.1678A>T APC variants in constitutional and tumor DNA, respectively. None of the constitutional APC variants occurred de novo and both tumors showed nuclear staining for β-catenin and no CTNNB1 variants. We present the first comprehensive characterization of the pathogenetic mechanisms of Gardner fibroma, which may be a sentinel lesion of previously unrecognized FAP families.

Introduction

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant disease caused by APC constitutional variants. It is characterized by the occurrence of multiple polyps in the colon and rectum that begin to develop, on average, at age 16 years.1 The mean age of colon cancer in previously undiagnosed individuals is 39 years and the penetrance is 100% in the typical forms of FAP.1 Extraintestinal manifestations of FAP include fibromatous soft tissue lesions, osteomas, dental abnormalities, and congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE). The APC gene encodes a large protein that is involved in the Wnt signal cascade by downregulating β-catenin.2, 3 When the APC function is lost, β-catenin accumulates and migrates to the nucleus, affecting proliferation, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis.4

Fibromatous soft tissue lesions, including desmoid-type fibromatosis and Gardner fibroma, may occur sporadically or as part of FAP.1, 5, 6, 7 The FAP-associated fibromatous soft tissue lesions often present β-catenin overexpression, which may result from activating somatic variants of the CTNNB1 gene (encoding the β-catenin) or from biallelic inactivation of the APC gene. As FAP patients are characterized by constitutional APC variants, they develop the disease when inactivation of the second allele occurs at the somatic level. The pathogenetic mechanisms of the rarer Gardner fibromas are still unknown. As 15–20% of constitutional APC variants occur de novo8 and fibromatous soft tissue lesions may be the first manifestation in FAP patients, genetic characterization of these tumors, especially in children, may help to identify FAP patients. We report the cytogenetic, molecular genetic, and immunohistochemical characterization of two Gardner fibromas, which allowed the identification of two previously unrecognized FAP families with constitutional APC variants.

Materials and methods

The first case was a 5-month-old child who had two lumbar subcutaneous nodules. The immunohistochemical study showed immunoreactivity for CD34 and negativity for α-smooth muscle actin and a diagnosis of Gardner fibroma was made. The second case was a 4-month-old child with a right scapular subcutaneous nodule with soft consistency. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a mass suggestive of a desmoid tumor. The immunohistochemical study showed immunoreactivity for CD34 and vimentin and negativity for α-smooth muscle actin and desmin, also consistent with Gardner fibroma. Owing to the association of Gardner fibroma with FAP, a recommendation for genetic counseling was made in both cases.

Chromosome banding analysis was performed in the first infant as sufficient fresh material was obtained. Clonality criteria and karyotype description followed the recommendations of the International System for Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN).9 The tumor of the second infant was analyzed by comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), as previously described.10, 11, 12 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses to assess APC (5q22.2) copy number in both tumors were performed with bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone RP11-124K18 targeting APC, labeled with SpectrumGreen (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA) conjugated nucleotides in nick translation reactions, as previously described.13

When the suspicion arose that these two patients could belong to previously unrecognized FAP families, genetic counseling was offered and detailed family history was obtained. After informed consent from the parents, the complete coding region and respective intron–exon boundaries of APC were screened for constitutional variants by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), protein truncation test (PTT), and/or direct sequencing, as previously described.14 Relatives were screened for the APC variants identified in the index patients by direct sequencing, following the criteria for genetic testing in FAP families. All APC variants described are according to LRG_130 (NM_000038.4) and to the Human Genome Variation Society guidelines, and were submitted to the APC LOVD database (http://www.insight-group.org/variants/database/).

Assessment of β-catenin immunoexpression was subsequently evaluated on both Gardner fibromas with the antibody Clone 17C2 (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) using the Novolink Polymer Detection System (Novocastra, Leica Microsystems), and the analyses was performed in a light microscopy by an experienced pathologist. Somatic exon 3 CNNTB1 variants were screened in tumor DNA by automatic sequencing, as previously reported.15 We searched for somatic APC variants in the second patient using the same approach as for the constitutional variant screening.

Results

Chromosome banding analysis of the tumor of the first infant revealed the following karyotype: 46,XY,del(5)(q11q35),der(11)(11pter->11q14::?::11q23->11qter)[16]/46,XY[4] (Figure 1a). The deletion of APC in 5q22.2 was confirmed by FISH (Figure 1b), which in an infant with Gardner fibroma was highly suggestive of a second hit in the context of a constitutional APC variant. After genetic counseling of the family, the constitutional APC variant c.4687dup, p.(Leu1563ProfsTer4), which is novel and predicted to be deleterious, was found (Figure 1c). Subsequent studies identified two additional family members carrying this variant and during genetic counseling we learned that the maternal grandmother had died with colorectal cancer and multiple polyps (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Genetic findings in the first infant. (a) Karyogram from the tumor biopsy, evidencing the del(5)(q11q35) among other chromosome changes. (b) Inverted DAPI image of the same metaphase demonstrating deletion of one APC copy (APC labeled in green). (c) Sequence electropherogram of the constitutional APC variant c.4687dup, p.(Leu1563ProfsTer4). (d) Family pedigree. CC, colon cancer; GF, Gardner fibroma; MD, mental disease; Os, osteoma; PP, poliposis; SC, sebaceous cysts. Numbers below symbols represent age at diagnosis or age of last observation, if unaffected.

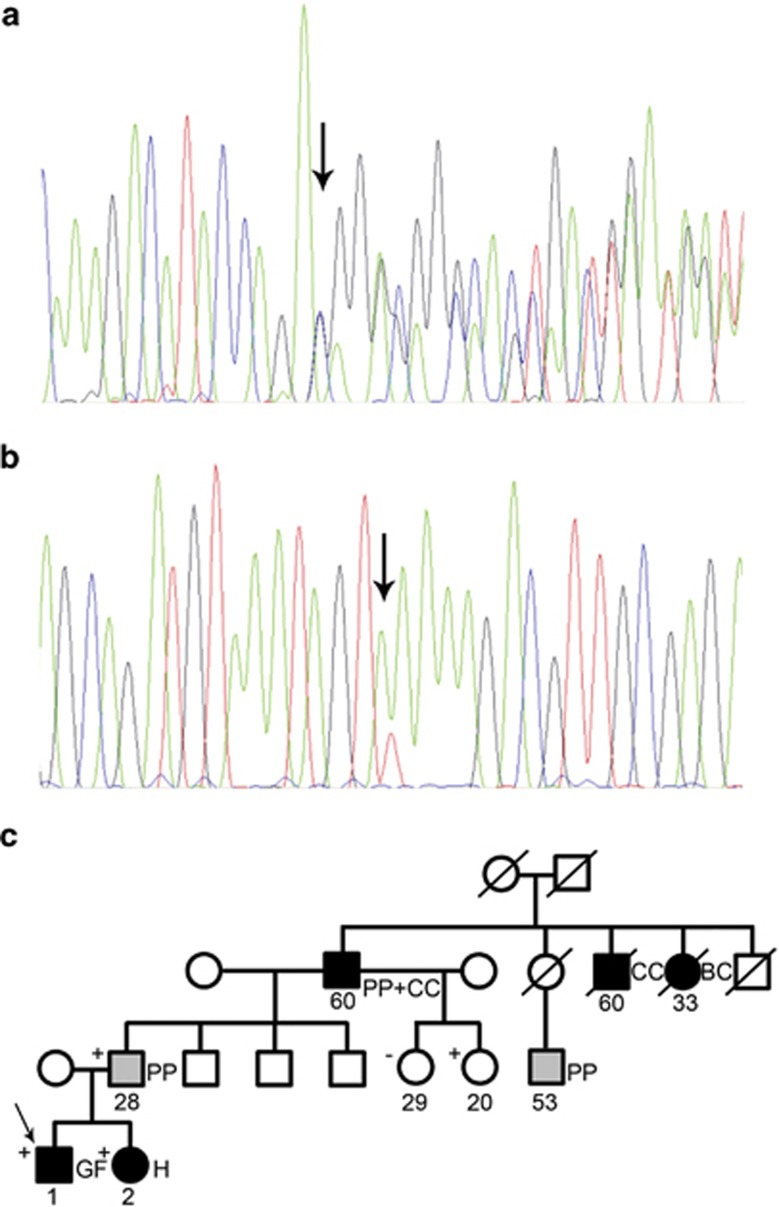

Analysis of constitutional DNA of the second infant with Gardner fibroma identified the deleterious APC variant c.5826_5829del, p.(Asp1942GlufsTer27) (Figure 2a). As no cytogenetic alterations were found (data not shown), we searched for APC somatic point mutations in the tumor DNA and the variant c.1678A>T, p.(Lys560Ter), was found (Figure 2b). During genetic counseling of the second family we learned that the proband had a two-year-old sister with hepatoblastoma, that the paternal grandfather had multiple polyps and colorectal carcinoma at the age of 60 years (diagnosed one year before), and that other distant relatives presented with multiple polyps, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer (Figure 2c). Subsequent genetic testing in the family uncovered three additional carriers of the constitutional APC variant, including the proband's sister with hepatoblastoma and their father.

Figure 2.

Genetic findings in the second infant. Sequence electropherograms of the constitutional (a) and somatic (b) APC variants c.5826_ 5829del, p.(Asp1942GlufsTer27), and c.1678A>T, p.(Lys560Ter), respectively. (c) Family pedigree. BC, breast cancer; CC, colon cancer; GF, Gardner fibroma; H, hepatoblastoma; PP, poliposis. Numbers below symbols represent age at diagnosis or age of last observation, if unaffected.

Both tumors showed nuclear staining for β-catenin (Figure 3), with absence of nuclear expression of β-catenin in normal cells, and sequence analysis of CTNNB1 exon 3 did not reveal any somatic variants (data not shown).

Figure 3.

H&E staining (a) and β-catenin nuclear immunoreactivity (b) of Gardner fibroma (both at × 100 magnification).

Discussion

The prevalence of desmoid-type fibromatosis in FAP is around 10 to 25% and in some families it is the first disease manifestation.16 These tumors have become an important cause of morbidity and even mortality.17 For these reasons, it is important to fully characterize pediatric desmoid-type fibromatosis to identify previously unrecognized FAP families. Indeed, two groups have recently proposed algorithms to characterize the pathogenetic nature of desmoid-type fibromatosis involving immunohistochemistry for β-catenin and somatic variant analysis of CTNNB1, eventually followed by constitutional APC variant analysis.18, 19 Gardner fibromas have been strongly associated with FAP, but the pathogenetic mechanisms originating these lesions are still largely unknown.6, 7 We here present the first comprehensive cytogenetic and molecular characterization of Gardner fibromas.

In the first proband, a 5q deletion including APC in a Gardner fibroma diagnosed in an infant was highly suggestive of an APC constitutional variant, which was confirmed after adequate genetic counseling. Somatic APC deletions are found in a high percentage of desmoid-type fibromatosis associated with FAP and this was the mechanism of somatic inactivation of the second allele also in this Gardner fibroma.20 The second infant with a Gardner fibroma also prompted genetic counseling and testing, and indeed a deleterious APC constitutional variant was also found. Interestingly, the second hit in this case was a novel APC somatic variant located outside the most common region in desmoids-type fibromatosis (codons 1324–1567).5, 21 The finding of biallelic APC inactivation, nuclear β-catenin expression, and the absence of somatic CTNNB1 variants indicates that there is a pathobiologic relationship between FAP-associated desmoid-type fibromatosis and Gardner fibroma, and indeed the former has been shown to originate at the site of the latter.6, 7

This work calls attention for the potential clinical importance of pathologists being able to recognize Gardner fibromas and shows that all such patients should be referred for genetic counseling of the family as they are very likely to be sentinel lesions of previously unrecognized FAP.22 CTNNB1 or APC somatic variants and APC copy number losses may be investigated to fully identify the pathogenetic mechanism of a given Gardner fibroma. Since variants in CTNNB1 and APC are expected to occur in a mutually exclusive manner, this would allow the identification of the second hit in FAP-associated Gardner fibromas or, perhaps more importantly, in case a constitutional variant is not found, to confirm the sporadic nature of the lesion by identifying a somatic CTNNB1 activating variant or two inactivating somatic APC variants. The characterization of the somatic pathobiologic mechanisms may additionally be helpful for differential diagnosis, for instance between Gardner fibroma and desmoplastic fibroblastoma (which is characterized by 11q12 rearrangements instead of 5q22.2/APC deletions or mutations).23 The confirmation of FAP diagnosis by the finding of a constitutional APC variant allows subsequent germline screening of family members at risk and adoption of prophylactic and therapeutic measures adequate to the syndrome in carriers, as shown in the two families we here present.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jasperson KW, Burt RW.APC-Associated Polyposis Conditionsin: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH et al: (eds)GeneReviews Seattle, WA, USA: University of Washington; 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss KH, Groden J. Biology of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1967–1979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson CA, Miller JR. Non-traditional roles for the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor protein. Gene. 2005;361:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodde R, Smits R, Clevers H. APC, signal transduction and genetic instability in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:55–67. doi: 10.1038/35094067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SK, Phillips RK. Desmoids in familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1494–1504. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrli BM, Weiss SW, Yandow S, Coffin CM. Gardner-associated fibromas (GAF) in young patients: a distinct fibrous lesion that identifies unsuspected Gardner syndrome and risk for fibromatosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:645–651. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200105000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin CM, Hornick JL, Zhou H, Fletcher CD. Gardner fibroma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 45 patients with 57 fibromas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:410–416. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213348.65014.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasen HF, Möslein G, Alonso A, et al. Guidelines for the clinical management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) Gut. 2008;57:704–713. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.136127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer LG, Slovak ML, Campbell LJ. An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Karger Publishers: Basel, Switzerland; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi OP, Kallioniemi A, Piper J, et al. Optimizing comparative genomic hybridization for analysis of DNA sequence copy number changes in solid tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;10:231–243. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro FR, Jeronimo C, Henrique R, et al. 8q gain is an independent predictor of poor survival in diagnostic needle biopsies from prostate cancer suspects. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3961–3970. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff M, Gerdes T, Rose H, Maahr J, Ottesen AM, Lundsteen C. Detection of chromosomal gains and losses in comparative genomic hybridization analysis based on standard reference intervals. Cytometry. 1998;31:163–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira J, Henrique R, Ribeiro FR, et al. Feasibility of differential diagnosis of kidney tumors by comparative genomic hybridization of fine needle aspiration biopsies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:935–947. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Luijt RB, Khan PM, Vasen HF, et al. Molecular analysis of the APC gene in 105 Dutch kindreds with familial adenomatous polyposis: 67 germline mutations identified by DGGE, PTT, and southern analysis. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:7–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:1<7::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A, Denkhaus D, Albrecht S, Leuschner I, von Schweinitz D, Pietsch T. Childhood hepatoblastomas frequently carry a mutated degradation targeting box of the beta-catenin gene. Cancer Res. 1999;59:269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturt NJ, Clark SK. Current ideas in desmoid tumours. Fam Cancer. 2006;5:275–288. doi: 10.1007/s10689-005-5675-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar C, Munker R, Thomas JO, Li BD, Burton GV. Update on desmoid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:562–569. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattentidt Mouravieva AA, Geurts-Giele IR, de Krijger RR, et al. Identification of Familial Adenomatous Polyposis carriers among children with desmoid tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1867–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WL, Nero C, Pappo A, Lev D, Lazar AJ, López-Terrada D. CTNNB1 genotyping and APC screening in pediatric desmoid tumors: a proposed alogrithm. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012;15:361–367. doi: 10.2350/11-07-1064-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robanus-Maandag E, Bosch C, Amini-Nik S, et al. Familial adenomatous polyposis-associated desmoids display significantly more genetic changes than sporadic desmoids. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejpar S, Nollet F, Li C, et al. Predominance of beta-catenin mutations and beta-catenin dysregulation in sporadic aggressive fibromatosis (desmoids tumor) Oncogene. 1999;18:6615–6620. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque S, Ahmed N, Nguyen VH, et al. Neonatal Gardner fibroma: a sentinel presentation of severe familial adenomatous polyposis. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1599–e1602. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchia G, Trombetta D, Möller E, et al. FOSL1 as a candidate target gene for 11q12 rearrangements in desmoplastic fibroblastoma. Lab Invest. 2012;92:735–743. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]