Abstract

Recent studies revealed the power of whole-exome sequencing to identify mutations in sporadic cases with non-syndromic intellectual disability. We now identified de novo missense variants in NAA10 in two unrelated individuals, a boy and a girl, with severe global developmental delay but without any major dysmorphism by trio whole-exome sequencing. Both de novo variants were predicted to be deleterious, and we excluded other variants in this gene. This X-linked gene encodes N-alpha-acetyltransferase 10, the catalytic subunit of the NatA complex involved in multiple cellular processes. A single hypomorphic missense variant p.(Ser37Pro) was previously associated with Ogden syndrome in eight affected males from two different families. This rare disorder is characterized by a highly recognizable phenotype, global developmental delay and results in death during infancy. In an attempt to explain the discrepant phenotype, we used in vitro N-terminal acetylation assays which suggested that the severity of the phenotype correlates with the remaining catalytic activity. The variant in the Ogden syndrome patients exhibited a lower activity than the one seen in the boy with intellectual disability, while the variant in the girl was the most severe exhibiting only residual activity in the acetylation assays used. We propose that N-terminal acetyltransferase deficiency is clinically heterogeneous with the overall catalytic activity determining the phenotypic severity.

Introduction

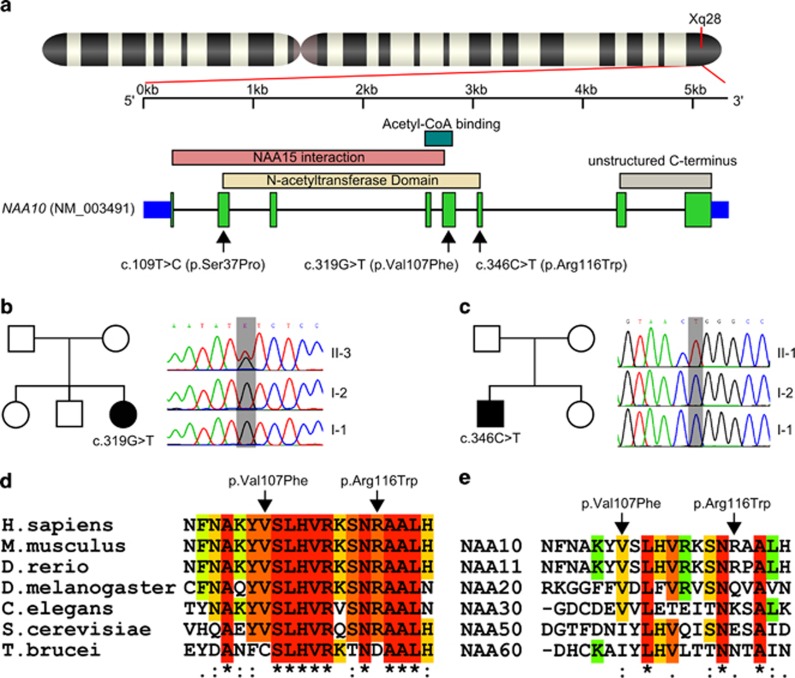

Naa10, the N-alpha-acetyltransferase 10, is the catalytic subunit of the N-alpha-acetyltransferase protein complex NatA. The NAA10 gene lies in the gene-rich region Xq28 and is composed of 8 exons (NM_003491.3; Figure 1a). It is highly expressed in the developing brain of mice embryos1 and shows a lower yet uniform and ubiquitous expression in adult mice.2 Complete knockout is lethal in Trypanosoma brucei,3 Caenorhabditis elegans4 and Drosophila melanogaster.5 The N-terminal two-thirds of the encoded protein show a globular conformation and contain a dimerization and the catalytic N-acetyltransferase domains, while the C-terminal third represents an unstructured flexible tail.6 By dimerization of Naa10 with the auxiliary subunit Naa15, the major N-acetyltransferase complex in eukaryotes – NatA – is formed.7, 8, 9, 10 This complex is not only responsible for acetylation of nascent polypeptides at the ribosomes11 but also shows non-ribosomal localization12 and posttranslational acetylation activity.13 The acetyl-coenzyme-A dependent N-alpha-acetylation is the most common protein modification with approximately 80–90% of all proteins in humans being modified by the NAT enzyme complexes (NatA-F),14 which differ in substrate specificity and subunit composition.15 For a long time, NAA10 has been studied as a cancer candidate gene,16, 17, 18 and it has been suggested to have a role in enzymatic and non-enzymatic regulation of dendrite growth,19 cell cycle control and apoptosis induction.20 This large number of cellular functions and the lethality in knockout model organisms is in accordance with the severe phenotype previously described in Ogden syndrome patients (MIM 300855). Rope et al21 described this new syndrome as a rare lethal X-linked disorder of infancy. Strikingly, the eight affected boys from two independent families showed the exact same inherited c.109T>C p.(Ser37Pro) variant in hemizygous state leading to a highly recognizable phenotype (see Table 1). The serine codon affected by this variant lies in exon 2 of the NAA10 gene within the dimerization domain with Naa15 and is highly conserved in eukaryotes.22, 23

Figure 1.

(a) Genomic position and domain structure of the NAA10 gene with positions of the herein described de novo variants (Exon 5/6) and the previously reported Ogden syndrome variant (Exon 2). Exons are numbered after NM_003491.3. The domain structure is based on the NCBI reference sequence NP_003482 and the recently described crystal structure of the NatA complex.23 (b, c) Pedigrees of the two singleton families and results of Sanger validation. (d) Amino-acid sequence alignment of Naa10 orthologs at the de novo variant positions shows high sequence conservation. (e) Amino-acid sequence alignment of Naa10 and known human NATs shows conservation of the N-acetyltransferase domain part containing the de novo variants. Protein sequences were obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser,34 and T-Coffee55 was used for alignment.

Table 1. Features of all individuals with NAA10 mutations.

| Rope et al21(n=8) | Esmailpour et al46/Forrester et al47 (n=4) | Family B Individual II-1 | Family A Individual II-3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant (NM_003491.3) | c.109T>C p.(Ser37Pro) | c.471+2T>A (p.Glu157fs45* p.0?) | c.346C>T p.(Arg116Trp) | c.319G>T p.(Val107Phe) |

| Inheritance | Inherited | Inherited | De novo | De novo |

| Gender | Male (8/8) | Male (4/4) | Male | Female |

| Age at last follow-up examination (*age of death) | 5–16 months* | 14–28 years | 5 years 11 months | 2 years 11 months |

| Postnatal growth failure | 8/8 | 4/4 | Yes | Yes |

| Developmental delay | Severe (8/8) | Severe (3/4), mild (1/4) | Severe | Severe |

| Facial | Large ears (6/8), down slanting palpebral fissures (4/8), prominent eyes (4/8), flared nares (3/8), hypertelorism (3/8), long philtrum (3/8) | Large abnormally formed ears (4/4), abnormally developed eyes (4/4), prominent philtrum (3/4) | Prominent forehead, deep set eyes, long eyelashes, down slanting palpebral fissures, large ears, diasthema | Long curved eyelashes, thin arched eyebrows, broad nasal bridge, thin arched upper lip |

| Skeletal | Large fontanels (5/8), broad or widely spaced toes (2/8), delayed osseous development (1/8) | High arched palate (4/4), clinodactyly (4/4), syndactyly (4/4), scoliosis (3/4), pectus excavatum (3/4), pes planus (2/4), abnormal teeth (2/4) | Small hands/feet, high arched palate, wide interdental spaces | Delayed closure of the fontanels, delayed bone age, broad great toes, mild pectus carinatum |

| Cardiac | Structural anomalies (6/8), arrhythmias (5/8) | Right ventricular hypertrophy (1/4) | — | Pulmonary artery stenosis, atrial septal defect, prolonged QT interval |

| Genital | Cryptorchidism (5/8), inguinal hernia (3/8) | — | Hypoplastic scrotum | — |

| Neurological | Truncal hypotonia (4/8), generalized hypertonia (1/8) | Hypotonia (4/4), seizures (2/4) | Truncal hypotonia, hypertonia of extremities, generalized epileptiform activity | Truncal hypotonia, hypertonia of extremities |

| Brain imaging | Cerebral atrophy or immature corpus callosum (3/8), enlarged ventricles (2/8) | Bilateral anophthalmia (3/4), microphthalmia (1/4) | Enlarged ventricles, reduced periventricular volume, gliotic changes | Borderline normal ventricles |

| Behavioural anomalies | Fussy and irritable (1/8) | Auto-aggressive behaviour (3/4), autistic features (2/4), mood-swings (1/4), hyperactivity (1/4) | Hyperactivity, auto-aggressive behaviour, hand biting, autistic features | Self-hugging, repetitive hand movements |

Recently, exome sequencing has been successfully applied in large studies to identify de novo mutations in cases of intellectual disability.24, 25 However, these studies mostly replicated known disease-associated genes. Due to the heterogeneity of the identified mutations, the authors could only imply previously not associated genes as causative based on de novo truncating mutations. As the de novo criterion, even in combination with a second mutation, is not sufficient to reach exome-wide significance and thus to establish pathogenicity, further replication studies in individuals with a similar phenotype and functional analysis of the new candidate genes are required.26, 27

Using exome sequencing in singleton trios, we identified two different de novo missense variants in the NAA10 gene in two unrelated patients, a girl and a boy, with severe but unspecific global developmental delay. Functional analyses of the novel as well as the previously published variants support causality and suggest a genotype–phenotype correlation.

Materials and methods

Clinical data

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty, Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, and by the Kantonale Ethikkommission Zurich, and written consent was obtained from parents or guardians of the patients.

Family A

The first patient (Individual II-3 of family A) was a girl aged 2 years and 11 months at the last investigation. She was born with normal birth weight and length, after an uneventful pregnancy as the third child of healthy non-consanguineous parents of German descent. As an infant, she had feeding problems and recurrent infections. She developed postnatal short stature with microcephaly. At the last physical examination, she had a height of 81 cm (−4.38 SD), a head circumference of 45.7 cm (−3.04 SD) and a weight of 10.3 kg. Her developmental course showed severe intellectual disability without regression. She could sit at age 2 years but does not walk or speak, so far. The girl has only minor unspecific dysmorphic features, the most obvious being long curved eyelashes, thin arched eyebrows, a broad nasal bridge and a thin arched upper lip. She showed distinct skeletal anomalies like delayed closure of the fontanels (age 2 years 1 month), a delayed bone age (1 year 6 months at age 2 years 9 months) and also broad great toes and a mild pectus carinatum. The girl was a floppy infant with initial hypotonia progressing to hypertonia of the extremities and truncal hypotonia later in life. Sonography of the brain showed borderline normal ventricles at 8 months of age. An MRI could not be performed due to respiratory arrest under propofol sedation. The patient shows stereotypic behaviours, such as self-hugging and repetitive hand movements. She also shows only little eye contact. As an infant, the girl had a systolic murmur, which led to identification of a pulmonary artery stenosis and an atrial septal defect. At 4 years and 8 months of age, her mother reported that a prolonged QT interval was identified by electrocardiography. No molecular testing has been performed, and there is no familial history for long QT-syndrome.

Standard karyotyping and genetic testing for Prader Willi, Angelman and Noonan syndromes, as well as sequencing of MECP2, TCF4 and CDKL5 were unremarkable as was a high-resolution chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA). The X-inactivation pattern was random.

Family B

The second patient (Individual II-1 of family B) was a boy aged 10 years 7 months, who was 5 years 11 months at the last physical examination. He was born with normal birth weight and length as the first child of healthy non-consanguineous parents of Swiss descent. Like the girl, this boy also developed postnatal growth retardation but to a lesser extent. At the time of investigation, he was 108 cm tall (−1.83 SD), had a head circumference of 50 cm (−1.68 SD) and a weight of 18 kg. He reached a social smile at age 6 months, could sit at age 18 months, started to walk independently at the age of about 6 years but did not develop speech or bowel or bladder control. Auto-aggressive behaviour with hand biting was a transient problem. He was able to drive a tree wheeler, was shy and hyperactive and needed constant supervision. Formal testing at the age of about 8 years showed severe intellectual disability with a developmental age of about 12 months and autistic features. He had minor unspecific dysmorphic facial features, such as a prominent forehead, deep-set eyes with long eyelashes, down slanting palpebral fissures and rather big ears. Also he had a high arched palate, wide interdental spaces and very small hands and feet. He had truncal hypotonia with hypertonia of the extremities.

Brain imaging through sonography showed enlarged ventricles and MRI scanning at the age of 5 years and 6 months revealed reduced periventricular volume and gliotic changes. Electroencephalography under photic stimulation showed generalized epileptiform activity.

Previous genetic testing for Angelman and Fragile X syndromes were unremarkable as was a high-resolution CMA. The healthy mother had a normal non-skewed X-inactivation.

Exome sequencing

For family A, enrichment for whole-exome sequencing was performed on DNA from individual II-3 and her parents using the SureSelect Human All Exon Kit V3 (50 Mb, ∼21000 genes) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Post-hybridization barcodes were used to allow multiplexing (Agilent Technologies). The Beckman Coulter SPRIworks (Beckman Coulter, Danvers, MA, USA) platform was used for the automated library preparation. Sequencing was carried out with 50 bp single reads on a SOLiD 4 system (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). On average, we obtained >125 million reads per individual. Read alignment to the hg19 reference genome was performed with the novoalignCS software V1.03.03 (NovoCraft Technologies, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia) and yielded approximately 80 million aligned reads on target per individual. The mean target coverage was 48, while 71 % of the target sequence was covered at least five times. Variant calling was performed using GATK UnifiedGenotyper v2.7 after removing duplicate reads, local realignment of indels and base-quality-score recalibration.28, 29 For the index patient, a total of 47385 SNVs and 4612 Indels were annotated using ANNOVAR.30 After applying filtering and manual inspection using the IGV browser31 only 1 potential de novo variant remained and was validated by Sanger sequencing (see Supplementary Table S2) in the patient and her parents. Paternity was confirmed using identity by state calculation with PLINK.32

The second patient was identified in an exome sequencing study of 51 patients with non-specific severe ID using an Illumina HiSeq2000 platform and has been briefly reported by Rauch et al24 Details on exome sequencing are described there.

The identified de novo variants were submitted to ClinVar (accessions SCV000154970 and SCV000154971) and to the LOVD gene variant database at http://www.lovd.nl/NAA10 (individual IDs 16948 and 16949).

Sanger sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from blood lymphocytes according to standard procedures. De novo variants were confirmed by PCR and bidirectional sequencing using the subjects' original DNA samples. The DNA samples were then screened for other NAA10 variants by bidirectional sequencing of all NAA10 exons (1–8; numbered after NM_003491.3), including flanking intronic regions. PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing were performed as previously described.33 Primer sequences (see Supplementary Table S3) were determined using the Exon Primer program from the UCSC genome browser,34 and primers were supplied by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Ulm, Germany).

In silico analysis and 3D homology modeling

Prediction of potential deleterious effects of missense variants detected in NAA10 was performed using the software tools SIFT,35 PolyPhen2,36 SNAP37 and PANTHER38 (see Supplementary Table S1).

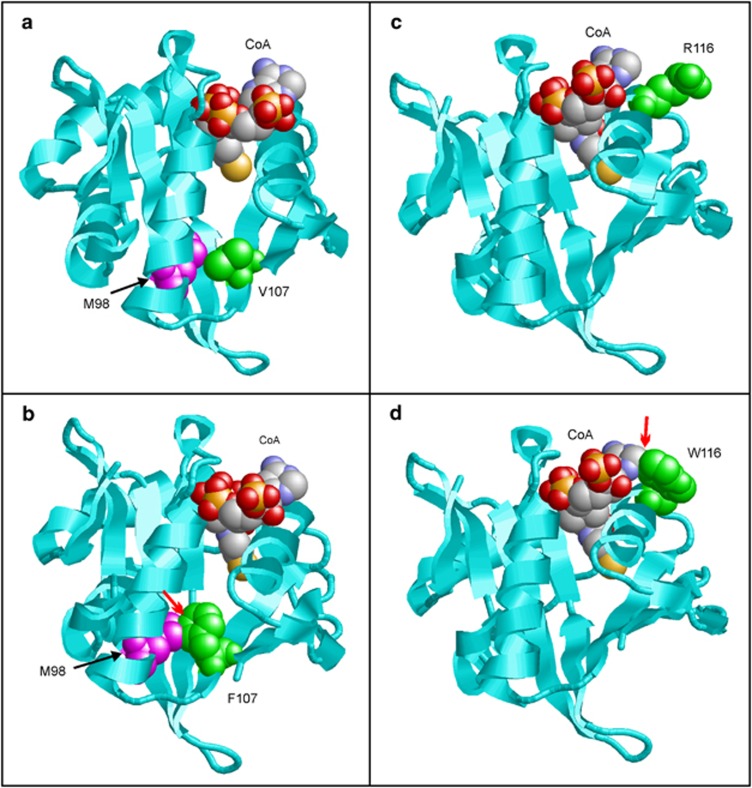

Both novel variants in Naa10 are located in the acetyltransferase domain, which was modeled using the structure of the homologous ARD1 domain from Sulfolobus as template (PDB code: 2X7B).39 Modeling of the wild-type (WT) proteins was performed using SwissModel.40 Variants were introduced in the structure by selecting the lowest-energy sidechain rotamer of the mutated residue. Energy minimization was performed using Sybyl7.3 (Tripos International, St Louis, MO, USA), and RasMol41 was used for structure analysis and visualization.

The WT and mutant proteins are shown in Figure 3, and the interpretation of their effect is given in the legend of the figure.

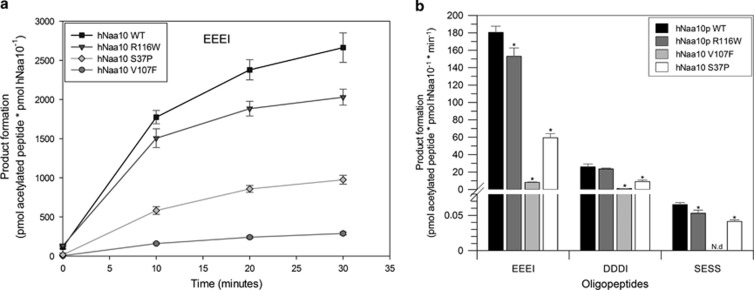

Functional analysis of the Naa10 variants

In order to examine the effects of the two variants on the catalytic activity of hNaa10, quantitative Nt-acetylation assays were performed. We analysed the catalytic activity of the two variants p.(Val107Phe) and p.(Arg116Trp) and compared the activity with Naa10 WT and the previously described p.(Ser37Pro) variant causing Ogden syndrome (Figure 4). The substrate peptides tested included a classical co-translational NatA substrate high-mobility group protein A1 with the N-terminus SESS,14 and two posttranslational Naa10 targets, EEEI and DDDI, representing the N-termini of γ-actin and β-actin, respectively.12

Plasmid construction and protein purification

Plasmids encoding MBP-Naa10 p.(Arg116Trp) and MBP-Naa10 p.(Val107Phe) were created by site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit, Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A pETM41 vector (G. Stier, EMBL, Heidelberg, Germany) encoding Naa10 WT with Maltose Binding Protein/His-fusion as a fusion tag was used as a template for the site-directed mutagenesis.12 Primers used for the mutagenesis were hNAA10 G319T f: 5′-CTTCAATGCCAAATATTTCTCCCTGCATGTCAGG-3′ and hNAA10 C346T f: 5′-GTCAGGAAGAGTAACTGGGCCGCCCTG-3′. Mutations were verified by Sanger sequencing and transformed into E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) by heat-shock transformation for protein expression. E. coli BL21 cells were grown in 200 ml cell cultures to an OD 600 nm, cultures were cooled down to 16 °C and protein expression was started by the addition of IPTG to a total concentration of 500 μM. After 14 h of incubation, cell cultures were harvested, and the pellet was stored on −20 °C. Pellets were dissolved in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7,4), 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 50 mM L-arginine, 50 mM L-glutamic acid and one tablet of EDTA-free protease inhibitor pr 50 ml), and cells were lysed by 6 × 60 s of short-pulse sonication on ice. Recombinant MBP-hNaa10 was purified by Immobilized Affinity Chromatography (HisTrap HP, GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and Size Exlusion Chromatography (Superdex 200 10/300, GE Healthcare). Buffers used for purification were: IMAC wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 50 mM L-arginine, 50 mM L-glutamic acid, 20 mM imidazole), IMAC elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 50 mM L-arginine, 50 mM L-glutamic acid, 300 mM imidazole) and Size Exclusion Chromatography buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 50 mM L-arginine, 50 mM L-glutamic acid). Fractions were analysed by SDS-PAGE, and protein concentration was determined by both A280 measurements (Nanodrop1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Quantitative in vitro acetylation assay

Purified recombinant MBP-hNaa10 was mixed with acetyl-CoA (600 mM), synthetic oligopeptides (300 mM) and acetylation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol), incubated at 37 °C and stopped after 10, 20 and 30 min by adding 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Product formation was quantified with RP-HPLC as described previously.42 In the quantitative acetylation assay, the following oligopeptides (Biogenes, Berlin, Germany) were used: EEEI ([H]EEEIAAL RWGRPVGRRRRPVRVYP[OH]) representing γ-actin, DDDI ([H]DDDIAAL RWGRPVGRRRRPVRVYP[OH]) representing β-actin and SESS ([H]SESSSKS RWGRPVGRRRRPVRVYP[OH]), representing high-mobility group protein A1.

Results

Previously, we described a probable disease-causing hemizygous de novo missense variant c.346C>T p.(Arg116Trp) in NAA10 in a boy (individual II-1 from family B) with severe developmental delay.24 Using exome sequencing, we now identified a further heterozygous de novo variant c.319G>T p.(Val107Phe) in a girl (individual II-3 from family A) presenting with severe global developmental delay (Figures 1a–c). Both individuals described here show severe global developmental delay, growth retardation and some overlapping features as summarized in Table 1 (see also Figure 2).

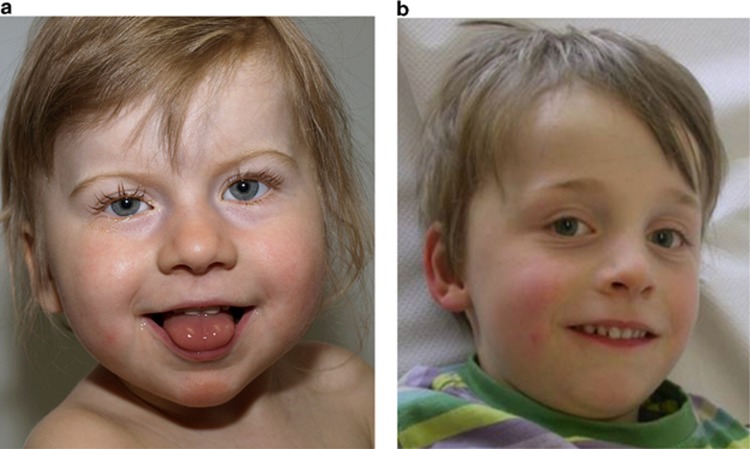

Figure 2.

(a) Individual II-3 of family A at age 2 years and 11 months. (b) Individual II-1 of family B at age 5 years and 11 months; only minor dysmorphisms and no syndromic features were observed.

Both variants were neither listed in dbSNP (build 137)43 nor in NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP; EVS-v.0.0.22, Oct. 17, 2013)44 database or the 1000 Genomes Project (release April 2012)45 and absent from in-house controls (c.319G>T: 434 SOLiD exomes; c.346C>T: 939 Illumina exomes). The de novo status was confirmed by Sanger sequencing in both cases. Additional Sanger sequencing of all coding exons showed no second variant in the girl.

Individual II-1 of family B also had two other de novo missense variants, namely in the KRT27 gene c.877G>C p.(Asp293His) and in the MYO1E gene c.1468G>A p.(Gly490Arg).24 These two variants were excluded as causative for the phenotype seen in this boy (see Supplementary Table S4 and discussion there).

The two identified de novo missense variants in the catalytic N-acetyltransferase domain of Naa10 affect highly conserved amino-acid residues both in orthologous and paralogous genes (Figure 1a, d and e). As in silico predictions using different algorithms classified both variants between benign and deleterious (Supplementary Table S1), we further studied them using 3D homology modelling. These protein structure-based predictions revealed that the Trp116 mutation most probably hampers CoA binding and reduces the enzymatic activity of Naa10, while the bulky mutant Phe107 side chain does not fit in the hydrophobic core of the protein and therefore might reduce protein stability or enzymatic activity of the protein (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structural effects of the p.(Val107Phe) and p.(Arg116Trp) variants in the acetyltransferase domain of Naa10 (cyan ribbon). The cofactor coenzyme A (CoA) is shown in space-filled presentation and coloured according to the atom type. The variant site is shown in green and key interacting residues in magenta. (a) Val107 is located in the hydrophobic core of the enzyme and tightly interacts with other hydrophobic residues, such as Met98. (b) Phe107 cannot be accommodated in the hydrophobic core due to its larger side chain and forms steric clashes with adjacent residues (denoted by a red arrow). These clashes are expected to cause protein unfolding and loss of enzymatic activity. (c) Arg116 is located close to the cofactor coenzyme A (CoA). (d) Trp116 preferentially adopts a side chain orientation that interferes with CoA binding. The steric clashes between Trp116 and CoA are indicated by a red arrow. These clashes are expected to hamper CoA binding and to reduce the enzymatic activity.

We next performed in vitro analysis of the mutant proteins through N-terminal acetylation assays with WT, both mutant proteins and the previously described missense variant to elucidate reduced catalytic activity as pathogenic mechanism. Of all the three known, presumably pathogenic missense variants, p.(Val107Phe) has the strongest reduction in activity and is almost catalytically dead (∼95% reduction in the catalytic activity) towards all three tested oligopeptides in comparison with Naa10 WT (Figure 4). The Naa10 p.(Arg116Trp) variant seen in the boy (Individual II-1 of family B) in contrast has a small but significant reduction in the catalytic activity for the oligopeptides EEEI and SESS (∼15% reduction in the catalytic activity) in comparison to Naa10 WT. This small effect greatly differs from the effects seen for the p.(Ser37Pro) variant, which has a reduction of catalytic activity ranging from 30 to 70% dependent of the substrate oligopeptide.

Figure 4.

In vitro N-terminal acetyltransferase activity of Naa10 variants. Purified recombinant hNaa10 WT and mutants were mixed with 300 mM oligopeptide and 600 mM acetyl-CoA and incubated at 37 °C. (a) Time-dependent acetylation of the oligopeptide EEEI by purified recombinant hNaa10 WT, hNaa10 p.(Arg116Trp), hNaa10 p.(Val107Phe) and hNaa10 p.(Ser37Pro). The reaction was stopped at different time points by the addition of 10% TFA. (b) NAT activity of hNaa10 WT and hNaa10 mutants towards substrate oligopeptides EEEI, DDDI and SESS. Bars are showing product formation in (or close to) the linear phase of the reaction, after 10 min of incubation. Measurements statistically significant from hNaa10 WT by independent two-tailed t-tests are indicated with an asterisk (P<0.05).

Discussion

We report two novel de novo missense variants in the NAA10 gene, c.319G>T p.(Val107Phe) and c.346C>T p.(Arg116Trp) in two patients with severe global developmental. We show that both variants significantly reduce the catalytic activity of the NAA10 gene product, an enzyme involved in N-terminal acetylation of proteins.

The two individuals described here, carrying de novo missense variants in the N-acetyltransferase domain, show a milder non-lethal phenotype without striking dysmorphic features, more similar to one another than to the cases described previously.21, 46 Although the most noticeable overlap in all patients with probably pathogenic variants in NAA10 is severe global developmental delay with postnatal growth failure and skeletal anomalies, individual II-3 of family A and individual II-1 of family B moreover share behavioural anomalies, truncal hypotonia with hypertonia of the extremities and some minor facial features (Table 1).

While this manuscript was in preparation, Esmailpour et al46 reported the identification of a splice-donor variant (c.471+2T>A) in the NAA10 gene in a family47 with Lenz microphthalmia syndrome. This variant resulted in no detectable normal NAA10 gene products but in different aberrant transcripts and low expression of a truncated protein.46 The four affected males described had congenital bilateral anophthalmia, postnatal growth failure, skeletal anomalies, hypotonia and moderate-to-severe mental retardation with a high degree of intra-familial variation.47 The authors also describe three heterozygous carrier females having mild symptoms with abnormally shaped ears, syndactyly of the toes, short terminal phalanges and short stature.47

All the affected boys in the two families reported by Rope et al.21 showed severe postnatal growth delay, severe developmental delay and some dysmorphic features. Also there were skeletal anomalies, structural anomalies of the heart and arrhythmias in electrocardiography. Death in all boys occurred between 5 and 16 months of age and was associated with cardiogenic shock or severe infection. Where performed, autopsy showed cerebral atrophy.21

Though Rope et al21 conducted in vitro acetylation assays and could show a 40–80% reduction in enzymatic activity for the mutant protein expressed in their patients, the underlying disease mechanism was not elucidated.21 To compare the remaining catalytic activity and thereby the severity of our two de novo variants, we performed N-terminal acetylation assays using all three missense variants described above. Despite only a small number of likely pathogenic distinct variants and uncertainty whether the in vitro results reflect the in vivo situation, our data implies a correlation between remaining catalytic activity of the particular NAA10 variant and the severity of the phenotype observed in each patient.

First, the high remaining activity of the p.(Arg116Trp) variant helps explain the relatively mild phenotype seen in the male patient when compared with the previously known males with Ogden syndrome (Figure 4). In males, no deletions spanning the NAA10 gene are known, although deletions upstream (MECP2) and downstream (L1CAM) of the gene are documented and cause distinct syndromes (MIM 300673 and MIM 303350) in males.48, 49 Thus, in accordance with the observed lethality of homozygous knockout in model organisms a complete loss-of-function of NAA10 seems to be lethal in hemizygous males. Altogether, as only hypomorphic mutations are present in males, it seems that more severe mutations, such as the p.(Val107Phe) variant, in hemizygous state might lead to an early intrauterine fetal death, which escapes analytical capabilities. This is further strengthened by the carrier mothers described by Esmailpour et al.46 having multiple spontaneous abortions.

The almost abolished catalytic activity for the p.(Val107Phe) variant seen in the girl could also account for her phenotype through a dominant-negative effect. This assumption is based on heterozygous female carriers previously being described as healthy and also large deletions encompassing the NAA10 gene being documented in the DECIPHER50 database in females with intellectual disability as phenotype when reported. The absence of deletions spanning the NAA10 gene in controls according to the Database of Genomic Variants51 can either point to the assumption that heterozygous loss-of-function in females is pathogenic or more likely that this relatively gene-dense region shows a low activity for genomic rearrangements. Consequently, as we excluded recessive inheritance to a great extent in the girl, an X-linked dominant mode of inheritance seems causative, either through a dominant-negative effect of the altered Naa10 protein in the NatA complex or a mixture of loss-of-function and dominant-negative effects. Although we excluded skewing of X-inactivation in blood, the phenotypic gap between the girl described here and the mothers of the Ogden families could also be explained by skewed X-inactivation in the nervous system. Indeed Esmailpour et al46 discussed the possibility of X-chromosome skewing for the mild manifestations in the heterozygous females carrying the c.471+2T>A splice-mutation. Also the variable expression and severity of clinical symptoms could be explained by yet unknown genetic modifiers (eg, variants in other NAT complex genes) or simply because missense mutations can have very diverse effects on the protein function.52 An example of another X-linked dominant disease showing a high phenotypic variability in female carriers is the Coffin-Lowry syndrome (MIM 303600); depending on the severity of the mutation in the RSK2 gene, females either have only minor manifestations or develop the full phenotype with facial dysmorphism, tapering fingers and skeletal deformities.53, 54

Although the inherited p.(Ser37Pro) variant lies close to the N-terminus in the dimerization domain and the c.471+2T>A variant leads to the truncation of the unstructured C-terminus, both de novo NAA10 variants lie in close proximity in the catalytic N-acetyltransferase domain. Taking into account the diverse cellular functions of the NatA complex, it is likely that these four variants show a different alteration in the NatA complex function. As a result, the affected boys in the two families described by Rope et al21 carrying the exact same missense mutation show a strikingly similar phenotype and the affected males in the family described by Esmailpour et al46 also show a comparable phenotype while the two patients described here have a more diverse phenotype.

For the first described pathogenic variant in NAA10, p.(Ser37Pro), Rope et al21 could show a hampered NatA activity towards synthetic peptides. For the newly described splice variant, the authors did not analyse the catalytic activity of the truncated protein but discussed that the absent expression of WT Naa10 and only minimal expression of mutant Naa10 would lead to reduced activity of the NatA complex in the patients' cells.46 Our results imply that reduced catalytic activity of the NatA complex is pathogenic. Still, as this complex acetylates about 38% of all human proteins,15 the downstream targets and molecular mechanisms in vivo remain unclear and other functions of Naa10 could influence the phenotype. Actually, Esmailpour et al.46 could show a loss of TSC2 interaction46 for the truncated Naa10 protein, and a recent study by Van Damme et al22 could prove a reduced NatA complex formation in vivo for the p.(Ser37Pro) variant. Further functional studies may provide more insight into the underlying pathogenic mechanism.

In conclusion, we have identified two de novo variants in NAA10 in two unrelated individuals Also we describe the first affected female, with severe global developmental delay and a de novo variant in NAA10. Identification of more individuals carrying new variants in NAA10 is needed to fully characterize the full phenotypic spectrum associated with N-terminal-acetyltransferase deficiency.

Finally, our study adds to the growing evidence that current syndrome descriptions are incomplete and strongly biased by phenotypic grouping in small-scale study. Thus unbiased large-scale sequencing approaches are needed to fully understand the complex relation between genotype and phenotype in human developmental diseases.24, 25

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families involved in this study for their participation. We thank Angelika Diem and Daniela Schweitzer for excellent technical assistance and Steffen Uebe and Arif Ekici for assistance in NGS. This manuscript is part of a doctoral thesis of Bernt Popp. We thank the Novocraft Technologies Company for granting a trial license of novoalignCS. This study was supported in part by the German Intellectual Disability Network (MRNET) through a grant from the German Ministry of Research and Education to André Reis (01GS08160), by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF 320030_135669) to Anita Rauch and by the Research Council of Norway, the Norwegian Cancer Society, Bergen Research Foundation (BFS) and the Western Norway Health Authorities to Thomas Arnesen.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Sugiura N, Adams S, Corriveau R. An evolutionarily conserved N-terminal acetyltransferase complex associated with neuronal development. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40113–40120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang A, Peacock S, Johnson W, Bear D, Rennert O, Chan W-Y. Cloning, characterization, and expression analysis of the novel acetyltransferase retrogene Ard1b in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:302–309. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram A, Cross G, Horn D. Genetic manipulation indicates that ARD1 is an essential N(alpha)-acetyltransferase in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;111:309–317. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sönnichsen B, Koski L, Walsh A, et al. Full-genome RNAi profiling of early embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;434:462–469. doi: 10.1038/nature03353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Mijares M, Gall M, et al. Drosophila variable nurse cells encodes arrest defective 1 (ARD1), the catalytic subunit of the major N-terminal acetyltransferase complex. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:2813–2827. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Puig N, Fersht A. Characterization of the native and fibrillar conformation of the human Nalpha-acetyltransferase ARD1. Prot Sci. 2006;15:1968–1976. doi: 10.1110/ps.062264006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polevoda B, Arnesen T, Sherman F. A synopsis of eukaryotic Nalpha-terminal acetyltransferases: nomenclature, subunits and substrates. BMC Proc. 2009;3 (Suppl 6:S2. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-S6-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen T, Anderson D, Baldersheim C, Lanotte M, Varhaug J, Lillehaug J. Identification and characterization of the human ARD1-NATH protein acetyltransferase complex. Biochem J. 2005;386:433–443. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Szostak J. ARD1 and NAT1 proteins form a complex that has N-terminal acetyltransferase activity. EMBO J. 1992;11:2087–2093. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen J, Kayne P, Moerschell R, et al. Identification and characterization of genes and mutants for an N-terminal acetyltransferase from yeast. EMBO J. 1989;8:2067–2075. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautschi M, Just S, Mun A, et al. The yeast N-acetyltransferase NatA is quantitatively anchored to the ribosome and interacts with nascent polypeptides. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7403–7414. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7403-7414.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme P, Evjenth R, Foyn H, et al. Proteome-derived peptide libraries allow detailed analysis of the substrate specificities of N(alpha)-acetyltransferases and point to hNaa10p as the post-translational actin N(alpha)-acetyltransferase. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M110. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsens K, Van Damme P, Degroeve S, et al. Bioinformatics analysis of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae N-terminal proteome provides evidence of alternative translation initiation and post-translational N-terminal acetylation. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:3578–3589. doi: 10.1021/pr2002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnesen T, Van Damme P, Polevoda B, et al. Proteomics analyses reveal the evolutionary conservation and divergence of N-terminal acetyltransferases from yeast and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8157–8162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901931106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starheim K, Gevaert K, Arnesen T. Protein N-terminal acetyltransferases: when the start matters. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JH, Cha JH, Park JH, et al. Arrest defective 1 autoacetylation is a critical step in its ability to stimulate cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4422–4432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua K-T, Tan C-T, Johansson G, et al. N-α-acetyltransferase 10 protein suppresses cancer cell metastasis by binding PIX proteins and inhibiting Cdc42/Rac1 activity. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C-F, Ou D, Lee S-B, et al. hNaa10p contributes to tumorigenesis by facilitating DNMT1-mediated tumor suppressor gene silencing. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2920–2930. doi: 10.1172/JCI42275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawa N, Sugisaki S, Tokunaga E, et al. N-acetyltransferase ARD1-NAT1 regulates neuronal dendritic development. Genes Cells. 2008;13:1171–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromyko D, Arnesen T, Ryningen A, Varhaug J, Lillehaug J. Depletion of the human Nα-terminal acetyltransferase A induces p53-dependent apoptosis and p53-independent growth inhibition. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2777–2789. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rope A, Wang K, Evjenth R, et al. Using VAAST to identify an X-linked disorder resulting in lethality in male infants due to N-terminal acetyltransferase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme P, Støve S, Glomnes N, Gevaert K, Arnesen T.A Saccharomyces cerevisiae model reveals in vivo functional impairment of the Ogden syndrome N-terminal acetyltransferase Naa10S37P mutant Mol Cell Proteomics 2014. e-pub ahead of print 9 January 2014doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liszczak G, Goldberg J, Foyn H, Petersson E, Arnesen T, Marmorstein R. Molecular basis for N-terminal acetylation by the heterodimeric NatA complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1098–1105. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch A, Wieczorek D, Graf E, et al. Range of genetic mutations associated with severe non-syndromic sporadic intellectual disability: an exome sequencing study. Lancet. 2012;380:1674–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ligt J, Willemsen M, van Bon B, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1921–1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Roak B, Vives L, Fu W, et al. Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science (New York, NY) 2012;338:1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1227764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amélie P, Claire R, Jean-Louis M. XLID-causing mutations and associated genes challenged in light of data from large-scale human exome sequencing. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:368–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo M, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson J, Mesirov J. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinformatics. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endele S, Rosenberger G, Geider K, et al. Mutations in GRIN2A and GRIN2B encoding regulatory subunits of NMDA receptors cause variable neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1021–1026. doi: 10.1038/ng.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng P. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3894–3900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg Y, Rost B. SNAP: predict effect of non-synonymous polymorphisms on function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3823–3835. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PD. PANTHER: a library of protein families and subfamilies indexed by function. Genome Res. 2003;13:2129–2141. doi: 10.1101/gr.772403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oke M, Carter L, Johnson K, et al. The Scottish structural proteomics facility: targets, methods and outputs. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2010;11:167–180. doi: 10.1007/s10969-010-9090-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F, Arnold K, Künzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayle R, Milner-White E. RASMOL: biomolecular graphics for all. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:374. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evjenth R, Hole K, Ziegler M, Lillehaug J. Application of reverse-phase HPLC to quantify oligopeptide acetylation eliminates interference from unspecific acetyl CoA hydrolysis. BMC Proc. 2009;3 (Suppl 6:S5. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-S6-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP): Bethesda, MD USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/ .

- Exome Variant Server: NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA, USA http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ .

- 1000 Genomes Project C. Abecasis G, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmailpour T, Riazifar H, Liu L, et al. A splice donor mutation in NAA10 results in the dysregulation of the retinoic acid signalling pathway and causes Lenz microphthalmia syndrome. J Med Genet. 2014;51:185–196. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester S, Kovach MJ, Reynolds NM, Urban R, Kimonis V. Manifestations in four males with and an obligate carrier of the Lenz microphthalmia syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:92–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knops NB, Bos K, Kerstjens M, van Dael K, Vos Y. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus in a patient with L1 syndrome: a new report of a contiguous gene deletion syndrome including L1CAM and AVPR2. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1853–1858. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick S, Reuter K, Williamson S, et al. Delineation of large deletions of the MECP2 gene in Rett syndrome patients, including a familial case with a male proband. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:1218–1229. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth H, Richards S, Bevan A, et al. DECIPHER: Database of Chromosomal Imbalance and Phenotype in Humans Using Ensembl Resources. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Feuk L, Duggan G, Khaja R, Scherer S. Development of bioinformatics resources for display and analysis of copy number and other structural variants in the human genome. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;115:205–214. doi: 10.1159/000095916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaaf CP, Sabo A, Sakai Y, et al. Oligogenic heterozygosity in individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3366–3375. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesler S, Simensen R, Voeller K, et al. Altered neurodevelopment associated with mutations of RSK2: a morphometric MRI study of Coffin-Lowry syndrome. Neurogenetics. 2007;8:143–147. doi: 10.1007/s10048-007-0080-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryssira H, Kountoupi S, Delaunoy JP, Thomaidis L. A female with Coffin-Lowry syndrome and "cataplexy". Genetic Couns. 2002;13:405–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C, Higgins D, Heringa J. T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:205–217. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.