Abstract

Study Objectives:

To assess adverse drug reaction reports of “abnormal sleep related events” associated with varenicline, a partial agonist to the α4β2 subtype of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on neurones, indicated for smoking cessation.

Design:

Twenty-seven reports of “abnormal sleep related events” often associated with abnormal dreams, nightmares, or somnambulism, which are known to be associated with varenicline use, were identified in the World Health Organisation (WHO) Global Individual Case Safety Reports Database. Original anonymous reports were obtained from the four national pharmacovigilance centers that submitted these reports and assessed for reaction description and causality.

Measurements and Results:

These 27 reports include 10 of aggressive activity occurring during sleep and seven of other sleep related harmful or potentially harmful activities, such as apparently deliberate self-harm, moving a child or a car, or lighting a stove or a cigarette. Assessment of these 17 reports of aggression or other actual or potential harm showed that nine patients recovered or were recovering on varenicline withdrawal and there were no consistent alternative explanations. Thirteen patients experienced single events, and two had multiple events. Frequency was not stated for the remaining two patients.

Conclusions:

The descriptions of the reports of aggression during sleep with violent dreaming are similar to those of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and also nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep parasomnias in some adults. Patients who experience somnambulism or dreams of a violent nature while taking varenicline should be advised to consult their health providers. Consideration should be given to clarifying the term sleep disorders in varenicline product information and including sleep related harmful and potentially harmful events.

Citation:

Savage RL, Zekarias A, Caduff-Janosa P. Varenicline and abnormal sleep related events. SLEEP 2015;38(5):833–837.

Keywords: aggression, nightmares, somnambulism, varenicline

INTRODUCTION

Varenicline is indicated as an aid for cessation of tobacco smoking. It binds as a partial agonist to the α4β2 subtype of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on neurones. It is postulated that varenicline reduces both craving for nicotine and nicotine withdrawal symptoms through its agonist activity at the receptors. At the same time it prevents nicotine binding to the receptors, thus blocking the ability of nicotine to stimulate the mesolimbic dopamine system, the neuronal mechanism underlying reinforcement and reward.1

Abnormal dreams (e.g., vivid, unusual) were reported commonly (12.4%) and at a greater frequency than with placebo (4.5%) in a pooled analysis of clinical trials of varenicline. Sleep disorders, unspecified and excluding insomnia and somnolence, were also reported commonly (4.8%) compared with a placebo rate of 2.8%. Nightmares and somnambulism have been reported since marketing and are listed in product information. Aggressive acts during wakefulness have also been reported.1–3

A pooled analysis of 10 randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials indicated that sleep disorders and disturbances occurred significantly more frequently with varenicline compared with placebo (relative risk [RR] 1.70 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.50–1.92]).4 Examination of the individual published trial results indicated that this group of adverse effects included insomnia, a recognized adverse effect of nicotine withdrawal, somnolence, abnormal dreams, and also in two trials, unspecified sleep disorder.5,6

In a study of reports of aggression in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) database, Moore et al.7 found that among 26 patients with well-documented reports of aggressive reactions during wakefulness occurring in a clear temporal association with varenicline use, 17 patients also experienced sleep disturbances or nightmares. In two reports the aggressive actions occurred directly on waking. Another patient was “kicking and screaming” during sleep.7

The WHO Global Individual Case Safety Reports Database (VigiBase®) holds details of suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) voluntarily reported by healthcare professionals and others to national pharmacovigilance agencies worldwide including those from the FDA AERS database.8 These reports are the chief source of information about medicines after they are marketed and may in themselves suggest changes and additions to product information or lead to further studies. The suspected adverse reactions in VigiBase are coded using the WHO Adverse Reaction Terminology (WHO-ART), a hierarchical system. Investigation of this database in 2013 revealed a range of sleep disorders related to varenicline use, including 143 reports of somnambulism and 2,642 reports of nightmares. Of concern was that some of these reports also included ADR terms indicating aggression or injury, although it was unclear whether these occurred during sleep. It was also noted that a WHO-ART low-level term “abnormal sleep related event” occurring under the preferred term “sleep disorder” appeared 27 times, usually together with somnambulism or nightmares. Because the preceding observations raised concern about the relationship between varenicline-related sleep disorders and harmful events and because unspecified sleep disorders had been reported in clinical trials, we conducted a systematic assessment of the original versions of the VigiBase reports that included the ADR term “abnormal sleep related event” to ascertain the nature of these events. This article presents the results.

METHODS

Original reports were requested for all of the 27 VigiBase reports that included the ADR term “abnormal sleep related event”. The reports came from the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US FDA; the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Authority, United Kingdom; the Canada Vigilance Program at Health Canada; and the Office of Product Review, Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australia, all of whom gave written consent for the case histories to be published in the form in which we submitted them. The reports were assessed to determine the nature of the events and potential contributory or alternative explanations.

RESULTS

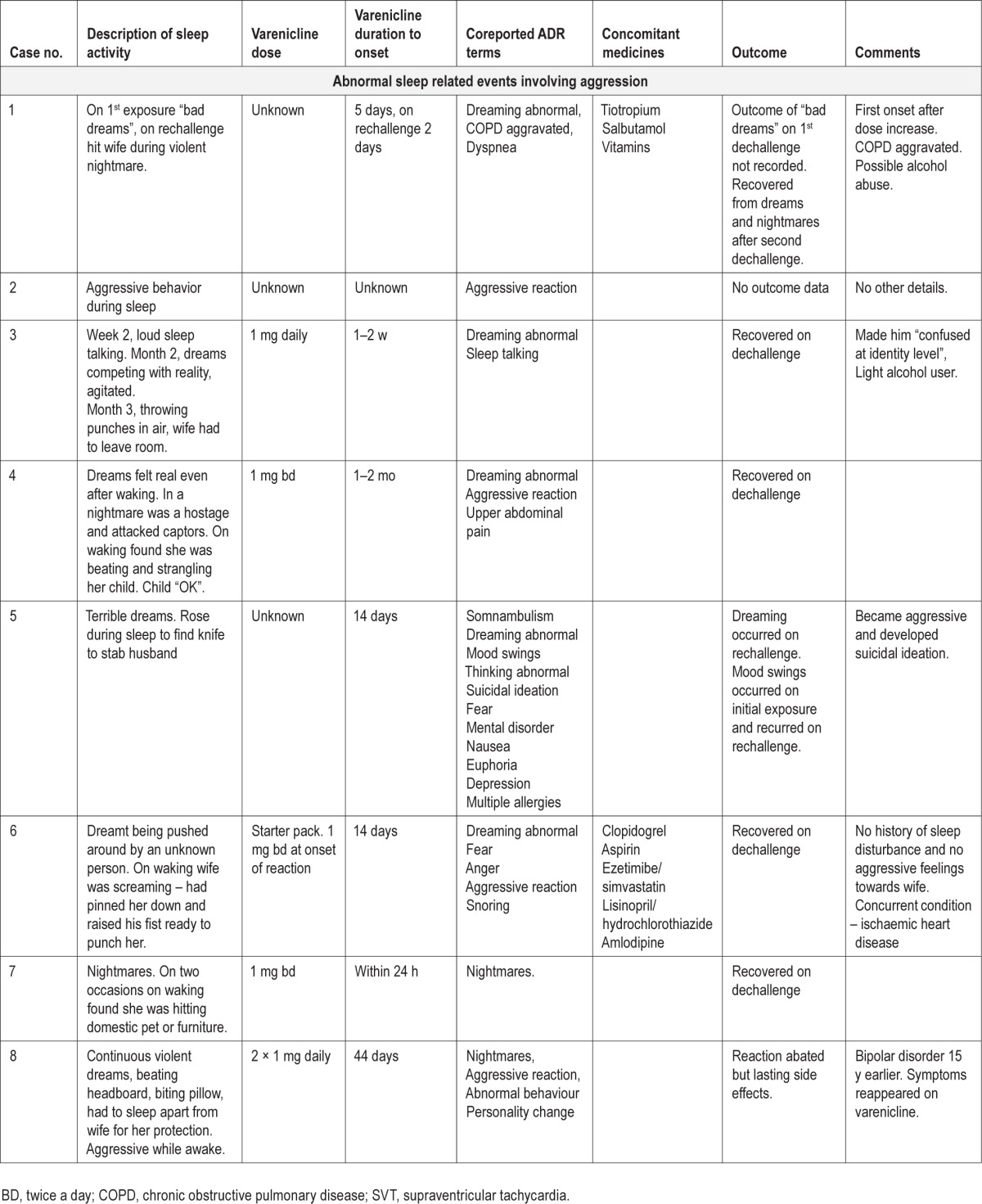

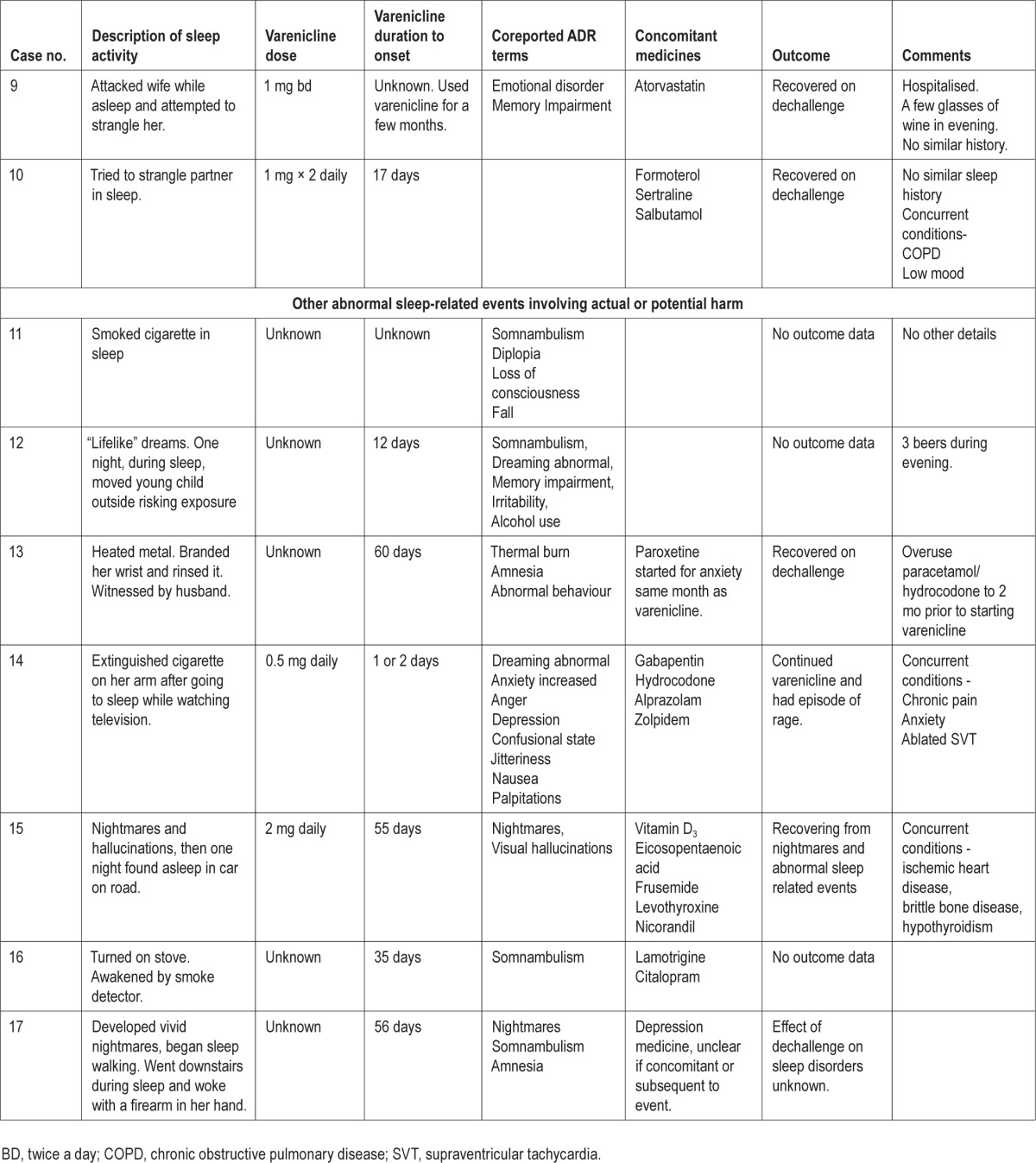

The reports describe 27 patients who became active during sleep. Ten patients became aggressive and seven exhibited non-aggressive harmful or potentially harmful activity (Table 1). The other 10 reports were miscellaneous and described non-harmful sleep activities such as talking, turning on lights, and dressing. However, six of these patients described abnormal dreaming or nightmares, usually involving activity. Four described being frightened and one pulled down wall fixtures.

Table 1.

Varenicline and sleep related harmful or potentially harmful events.

Sleep Related Aggression

These 10 reports (Table 1, cases 1–10), five from health care professionals and five from the patients or others, involved six males and four females. The age range was 44 to 63 y, mean 53.5 y. Duration of varenicline use to onset, where stated (eight patients), ranged from 1 day to between 1 and 2 mo. Six patients experienced the reaction within the first 17 days, whereas for the other two patients duration of varenicline use to onset was reported as 44 days and between 1 and 2 mo. Varenicline daily dose, recorded for only three patients, was 2 mg. In one patient the reaction occurred after a dose increase. Given the duration to onset, two patients would have been taking increasing doses at onset and four would have reached the maximum recommended daily dose of 2 mg in the preceding 3 to 10 days, assuming they were following the dose guidelines.

Potential contributory or alternative explanations were explored. One patient had suspected alcoholism and one had been drinking alcohol in the evening. The patient with suspected alcoholism and two others had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). One patient had a preexisting mental illness. Statements were made in three reports that there was no similar past history; in the others this information was not provided. No patients were on record as taking psychoactive medicines. Two patients were taking statins, which have been reported to cause aggressive reactions.9 However, both recovered when they stopped varenicline use.

In some reports it is possible that the aggression was nondirected; for example, the patient was making punching movements during sleep and accidentally hit his or her partner. In other reports, there was a more directed assault usually directed at a person in a violent dream, but in reality the bed partner was almost or actually assaulted. Where memory impairment was listed as a coreported adverse reaction term, it was usually to signify that the patient could not remember the events after waking. On other occasions the patients woke as they were attacking or about to attack.

Six reports described single episodes of aggression, four with abnormal dreams or nightmares occurring over several nights leading up to the event. Multiple episodes of aggression in the context of abnormal dreams or nightmares were described in two reports. The frequency of the episodes was not clear in the other two reports. Of the six patients who experienced single aggressive events, five stopped varenicline immediately.

One patient also reported somnambulism, one sleep talking, and one visual hallucinations. Five patients described daytime psychiatric symptoms including euphoria, depression, aggression, and suicidal ideation (case 5), fear because of the aggressive event (case 6), aggression, personality change and reappearance of bipolar disorder symptoms (case 8), severe emotional upset due to the aggressive event (case 9), and confusion at an identity level because of the vivid dreams (case 3). The descriptions of the dreams as shown in Table 1 indicate their very unpleasant and vivid nature.

Seven patients recovered when they stopped varenicline use. These seven patients include five of the six who experienced a single aggressive event and stopped varenicline use immediately. One improved but the reactivated symptoms of bipolar disorder persisted. One patient experienced “bad dreams” (case 1) and one mood disorder (case 5) on first exposure to varenicline. On rechallenge, these symptoms recurred and the patients also developed nightmare-related aggression.

Sleep Related Harmful or Potentially Harmful Nonaggressive Activities

These seven reports (Table 1, cases 11 through 17), three from healthcare professionals and four from the patients or others, involved four females and three males. The age range was 29 to 63 y and the mean age, 44.7 y, was a little younger than the group with aggression. Duration of varenicline use to onset was longer, ranging from 14 to 55 days. In five of these reports, the patients experienced somnambulism and the activities appeared to be usual daily activities that were dangerous because they occurred during sleep. These are known features of sleepwalking. However, two patients caused what appeared to be deliberate self-harm during sleep (Table 1, case reports 3 and 4). These acts seem more in keeping with the acts of aggression. All of the reports describe a single harmful or potentially harmful event. However, one patient who self-harmed and two others had abnormal dreams or nightmares, one with hallucinations, leading up to the event. Again, these symptoms are not typically described with somnambulism. Two patients described daytime psychiatric symptoms, irritability (case 12) and anxiety, confusion, depression, and rage (case 14).

Unlike the reports of aggression, four patients were taking psychoactive medicines (including the two who self-harmed). One patient had consumed a moderate amount of alcohol in the evening. One patient had a history of psychiatric symptoms and another of drug dependence. There was no information in any of the reports indicating whether the patients had a history of parasomnias.

Information on outcome was only provided in three reports, with two patients recovering after stopping varenicline use and one who continued its use and had an episode of rage.

DISCUSSION

We have presented two series of case reports of suspected adverse reactions to varenicline, all assigned the WHO ART term, “abnormal sleep related event”. In the first series (Table 1, cases 1–10) most patients experienced vivid dreams, often nightmares, and all became actively aggressive during sleep. In the second series (Table 1, cases 11–17), most patients were sleepwalking and their activities while asleep were potentially or actually harmful. Some activities were extreme, such as risking exposure to a young child and self-harm.

Product information for varenicline lists somnambulism, nightmares, sleep disorders, and aggression as adverse reactions but does not indicate that aggression might, on occasions, be part of sleep related activity.1,2 As the specific nature of the sleep disorders is not stated it is unclear if they involved sleep related activity. However, the finding by Moore et al. of an association between aggression during wakefulness and sleep disturbances appears relevant, and it is of interest that in this study the duration of varenicline use to onset of initial symptoms, recorded for 18 of 26 patients, ranged from 1 to 14 days, similar to the range found in most VigiBase reports of sleep related aggression.

In assessing psychiatric reports associated with varenicline use, it is often difficult to distinguish between adverse effects of the medicine and those of nicotine withdrawal. Insomnia and increased recall of vivid dreams have been described in association with nicotine withdrawal. However, nightmares and violent dreams with aggressive activity and somnambulism are not usually listed as typical nicotine withdrawal symptoms.10

Hypoxia caused by COPD and excess alcohol may both contribute to aggressive behavior but these factors, although present, were not consistent explanations in the reports in Table 1. All of the patients who had consumed alcohol or who had COPD recovered when varenicline was discontinued, as did the two patients taking statins. Injurious behavior is known to occur during severe forms of sleepwalking as patients undertake normal daily activities such as cooking or driving a car.11 The two reports of seemingly deliberate self-injury (cases 13, 14) are more in keeping with the sleep related aggression reports, only one of which was associated with somnambulism. An unusual feature of our reports was the association of abnormal dreaming, hallucinations, and nightmares with somnambulism. It would appear that, although there are similarities, not all the sleep related events can be categorized as somnambulism.

Parasomnias have been described as undesirable physical events or experiences that occur during entry into sleep, within sleep, or during arousals from sleep.12 The behaviors can be complex and appear purposeful but the patient has no conscious awareness of these. Sleepwalking is a nonrapid eye movement (NREM) parasomnia, which is a disorder of arousal. There are also rapid eye movement (REM)-related parasomnias that involve the intrusion of the features of REM sleep into wakefulness, e.g., nightmares and lack of REM-related atonia. Aggressive behavior during sleep has been associated with both NREM and REM sleep disorders.13 A rare disorder known as REM sleep behavior disorder is also described. Agitated or violent behavior occurs during sleep and injury to the bed partner is not uncommon. Upon waking, the patient often reports vivid and frequently unpleasant dreams. Although this disorder typically occurs in older men, many of whom have or later develop neurologic disease, especially Parkinson disease, the description is remarkably similar to the VigiBase reports 1–10 in Table 1.14 Although no lasting serious physical harm was described in our reports, both REM and NREM parasomnias, when they involve injurious behavior, can have serious consequences and forensic implications.13,14

It is acknowledged that the information in VigiBase is heterogeneous, i.e., it originates from multiple sources (different countries and types of reporters) and the amount of information given, as well as the likelihood that the medicine caused the adverse reaction, may vary from case to case. Nevertheless, given the association with unpleasant and violent dreams or nightmares in the study by Moore et al. of aggression with varenicline and in the VigiBase reports of sleep related aggression or harm we have presented, it would seem wise to advise patients to consult their health providers if such dreaming occurs, especially if the dreams are of a violent nature or associated with psychiatric symptoms. When patients report vivid and disturbing dreams, the nature of these should be elucidated. Consideration should also be given to clarifying the term “sleep disorders” listed as an adverse reaction to varenicline in product information.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. The work was performed at the Uppsala Monitoring Centre, Uppsala, Sweden.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are indebted to the National Centers that contributed data. The opinions and conclusions in the study are not necessarily those of the various centers or of the WHO.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pfizer Ltd. Champix 0.5 mg film-coated tablets. [Accessed April 3, 2014]. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000699/WC500025251.pdf.

- 2.Pfizer New Zealand Ltd. Champix Film coated tablet. [Accessed April 3, 2014]. http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/datasheet/DSForm.asp.

- 3.Harrison-Woolrych M, Ashton A. Psychiatric adverse events associated with varenicline. An intensive postmarketing prospective cohort study in New Zealand. Drug Saf. 2011;34:763–72. doi: 10.2165/11594450-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonstad S, Davies S, Flammer M, Russ C, Hughes J. Psychiatric adverse events in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials of varenicline. A pooled analysis. Drug Saf. 2010;33:289–301. doi: 10.2165/11319180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, et al. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist vs placebo or sustained release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore TJ, Glenmullen J, Furberg CD. Thoughts and acts of aggression/ violence toward others reported in association with varenicline. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1389–94. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindquist M. Vigibase, the WHO Global ICSR Database System: basic facts. Drug Inf J. 2008;42:409–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatley M, Savage R. Psychiatric adverse reactions with statins, fibrates and ezetimibe: implications for the use of lipid-lowering agents. Drug Saf. 2007;30:195–201. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes JR. Effects of abstinence from tobacco: valid symptoms and time course. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:315–27. doi: 10.1080/14622200701188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zadra A, Desautels A, Petit D, Montplaisir J. Somnambulism; clinical aspects and pathophysiological hypotheses. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:285–94. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahowald MW, Schenk CH, Cramer Bornemann MA. Violent parasomnias; forensic implications. In: Montagna P, Chokroverty S, editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 1149–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenck CH, Lee SA, Cramer Bornemann MA, Mahowald MW. Potentially lethal behaviors associated with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: review of the literature and forensic implications. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54:1475–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]