Abstract

Tumor protein D52-like 2, known as hD54 in previous studies (TPD52L2), is a member of TPD52 family which has been implicated in multiple human cancers. In recent reports, TPD52 proteins were indicated to be associated with several malignancies, but very little is known about the function of TPD52L2 in liver cancers. In our present study, in order to explore the role of TPD52L2 in liver cancer, TPD52L2 was knocked down in SMMC-7721 liver cancer cell line by lentivirus mediated RNA interference. The results demonstrated that depletion of TPD52L2 could remarkably inhibit proliferation and colony forming ability of cancer cell SMMC-7721. Furthermore, cell cycle in TPD52L2 depleted cells was verified to be arrested in G0/G1 phase as determined by FACS assay, in consistence with the observation of cell proliferation inhibition. These results unraveled that TPD52L2 played an important role in tumorigenesis pathways of liver cancer and might serve as a promising target in human liver cancer diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords: TPD52L2, liver cancer, RNA interference, lentivirus, proliferation

Introduction

Liver cancer is the most common human cancer over the world. In men it is the fifth most frequent cancer and the second most frequent cause of cancer-related death [1]. Half of the new liver cancer cases and cancer deaths are found in China [1] and it occurred 754,000 new deaths in 2010 [2]. Incidence and mortality rates have a strong male predominance (3 to 1) and age gradient in liver cancer [3]. Although the diagnosis and treatment have been improved for liver cancers but the five year survival rate was not satisfying and does not exceed 40% [4]. Therefore the therapeutic biomarkers for liver cancers are in urgent needs to human society.

Extensive analyses of proteome of cells grown abnormally always provide important information about pathological process that takes place in the cells. Scientists employed proteomic analyses to identify new cancer biomarkers and disease-associated targets [5,6]. The first TPD52 gene was identified as being over-expressed in human breast carcinomas [7]. Afterwards, the expression level of TPD52 was reported to be elevated in multiple human cancers, including lung [8,9], prostate [10-12], colon [13], and ovary [14]. Further studies demonstrated that TPD52 gene encodes regulators of cancer cell proliferation, indicating that TPD52 may be important for maintaining tumorigenesis and metastasis of cancer cells [15]. The human TPD52 gene family comprises four genes, hD52 [7,10], hD53 [15,16], hD54 [17,18], and hD55 [19]. It was once reported that tumor protein D52-like 2 isoform (TPD52L2, previously known as hD54) was upregulated together with nuclear protein (HNRNP-K) in HCC cell line Huh7 cells [20]. But its direct silencing effect and molecular mechanism control via carcinoma metastasis is yet not elucidated.

In this present study, we sought to further investigate the role of TPD52L2 in liver cancer cells proliferation by employing a much more direct and effective tool, RNAi technique, to carry out loss-of-function assays [21,22]. To our knowledge, this is the first presentation providing clear evidence that knockdown of endogenous TPD52L2 could suppress the proliferation of liver cancer cells and induce cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase. We shed light on the promising therapeutic value of TPD52L2 against human liver carcinoma for future clinical applications.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Both human embryonic kidney cell line 293T (HEK293T) and human hepatic carcinoma cell line SMMC-7721 were obtained from Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Cells were maintained in DMEM medium (Hyclone SH30243.01B+, Logan, UT, USA), supplemented with 10% FBS (Biowest, Kansas City, MO, USA) at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Construction of lentiviral vector expressing TPD52L2-specific shRNA

A candidate short hairpin RNA (shRNA) was screened and validated to be target sequence (5’-GCGGAGGGTTTGAAAGAATATCTCGAGATATTCTTTCAAACCCTCCGCTTTTTT-3’, sequence 1) against human TPD52L2 gene (NM_199360). And the negative control siRNA was 5’-GCGGAGGGTTTGAAAGAATATCTCGAGATATTCTTTCAAACCCTCCGCTTTTTT-3’. The stem-loop-stem oligos (shRNAs) were synthesized, annealed, and ligated into the NheI/PacI-linearized shRNA vector pFH-L (Shanghai Hollybio, China). The lentiviral-based shRNA-expressing vectors were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The generated plasmids were named as pFH-L-shTPD52L2 and pFH-L-shCon.

HEK293T cells (1.0 × 106) were seeded into 10-cm dishes and cultured for 24 h to reach over 80% confluence. The medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM two hours before transfection. The plasmids including 10 µg of pFH-L-shTPD52L2 or pFH-L-shCon, 7.5 µg of pHelper plasmids pVSVG-I and 5 µg of pCMVΔR8.92 were added to the cells with 0.95 ml of Opti-MEM and 50 µl of Lipofectamine 2000. The mixture was incubated for 8 h before replacing the medium with 10 ml of complete DMEM medium (supplemented with 10% PBS).

Lentiviral particles were harvested in 96 h after transfection. SMMC-7721 cells were cultivated in 6-well plates at the density of 5 × 104 cells/well and inoculated with recombinant lentiviruses (Lv-shCon or Lv-shTPD52L2) at an MOI of 30. The infection efficiency was determined by counting the numbers of GFP-expressing cells under fluorescence microscope.

Analysis of TPD52L2 knockdown in SMMC-7721 cells by quantitative real-time PCR

Expression of TPD52L2 mRNA in the human hepatic cancer cell line SMMC-7721 with or without vector transfection was detected, with actin as a normalizing control. TPD52L2 forward: 5’-TTCCAGGCAGGACAGAAGA-3’ and reverse: 5’-TTGAAGGTCGCAGAGTTCCT-3’; actin forward: 5’-GTGGACATCCGCAAAGAC-3’ and reverse: 5’-AAAGGGTGTAACGCAACTA-3’. Infected SMMC-7721 cells were trypsinized and harvested 5 days after transduction. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Gibco RL, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. 5 μg of total RNA was used to synthesize the first strand of cDNA using SuperScript II RT 200 U/ml (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Two step real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR (real-time RT PCR) reactions were performed using BioRad Connet Real-Time PCR platform (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA), which included cycle 1 (1 ×): 95°C, 1 min; and cycle 2 (40 ×): 95°C, 5 s; 60°C, 20 s. Absorbance data were collected at the end of every extension (60°C) and graphed using embedded software. The real-time PCR data were analyzed by 2-ΔΔCt.

Western blot analysis

Before applying western blot analysis we cultivated SMMC-7721 cells and infected with recombinant lentiviruses for 8 days. The cells were washed twice with PBS, homogenized in cell lysis buffer (10 mM EDTA, 4% SDS, 10% Glycine in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8). Individual samples each containing 60 µg protein, were separated on a pre-cast 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel in a Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.4) and blotted onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) at 300 mA for 1.5 h. The membrane was incubated at room temperature for 1 h in PBST buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 0.05% Triton-100), containing 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) to block nonspecific protein binding sites. Then the membrane was probed with a goat anti-TPD52L2 antibody (Sigma, SAB501053, 1:500 dilution) and rabbit anti-GAPDH antibody simultaneously (Proteintech Group, 10494-1-AP 1:100000 dilution) overnight at 4°C, followed by 5 washes with PBST. Blots were then incubated with secondary antibodies, a donkey-anti-goat HRP (1:5000) (Beyotime, China, A0181) and subsequent goat-anti-rabbit HRP (1:5000) (Santa Cruz, SC-2054), for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, the blots were visualized by super ECL detection reagent (Applygen, Beijing, China).

MTT viability assay

SMMC-7721 cells were co-cultivated with lentivirus at MOI 30 for 96 h. Cells were washed and re-seeded in 96-well plates with 2500 per well. Adequate MTT solution (10% SDS, 5% isopropanol and 0.01 M HCl) was added to each well for 10 min at 37°C, then the formazan crystals were solubilized with 100 ml of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate in 0.01 M HCl for 24 h. The optical density was measured using microplate reader at the wavelength of 595 nm. The cell count and optical density were carried out daily within 5 days.

Colony formation assay

SMMC-7721 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates at a density of 500 cells per well and allowed to grow for 8 days to form colonies. Colony cells were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. The number of colonies with more than 50 cells per colony was manually counted under microscope.

Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

The infected SMMC-7721 cells were harvested and re-inoculated into 6-cm dishes at a density of 8 × 104 cells per dish. After 40 h of incubation SMMC-7721 cells were trypsinized and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cellular DNA was stained by propidium iodide (PI) to determine the cell cycle change. Tests were performed in triplicate and analyses were performed by FAC Scan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) in respect to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS13.0 software. The differences between groups were compared using Student’s test, and data were expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significant difference was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

TPD52L2 specific siRNA efficiently downregulated endogenous expression level

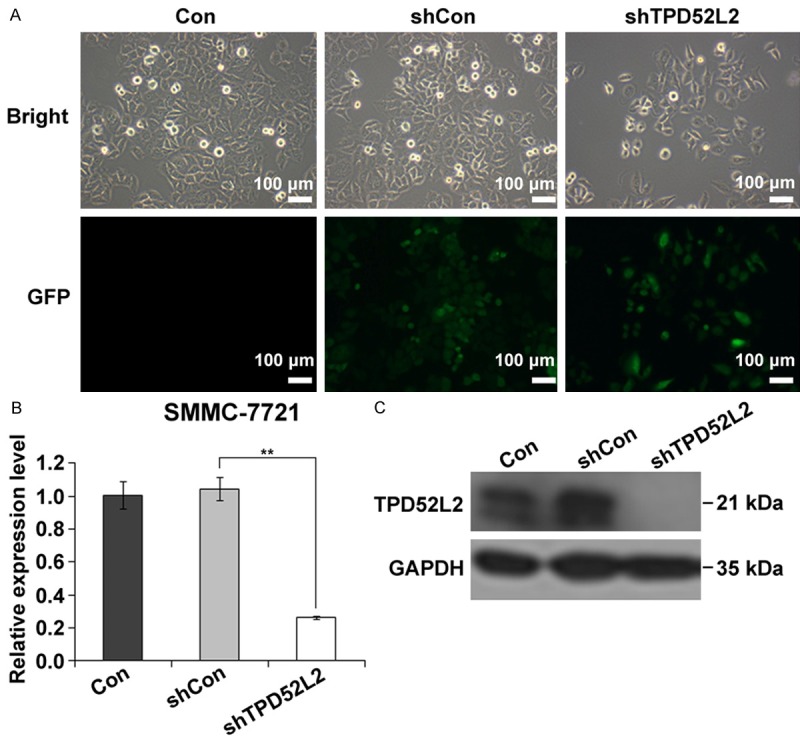

To explore the role of TPD52L2 in liver cancer, we performed a loss-of-function assay by RNA interference, and both control lentivirus (Lv-shCon) and specific TPD52L2-targeting lentivirus (Lv-shTPD52L2) were constructed. Human liver cancer cell line SMMC-7721 cells were cultivated and infected respectively with Lv-shCon or Lv-shTPD52L2. Negative control of cells were cultured without lentiviral infection (Con). Embedded GFP can provide visual fluorescence under microscope. As shown in Figure 1A, over 80% of SMMC-7721 cells were GFP positive, indicating a satisfying infection efficacy. To determine the silencing efficiency, the expression levels of TPD52L2 mRNA were detected. In Figure 1B, the non-silencing lentivirus encoded with irrelevant sequence had negligible effect on TPD52L2 expression, but the TPD52L2-silencing lentivirus significantly down-regulated the mRNA expression by 74.9% (P < 0.001). Concurrently the protein levels were monitored by Western Blot. In Figure 1C we demonstrated that the protein expression of TPD52L2 in SMMC-7721 cells was noticeably deprived whilst control groups (Con and shCon) were maintaining the invariable expression level. Taken together, the lentiviruses we have constructed provided assuring knockdown efficiency and ensure us an efficient vector system to study the knockdown effect of TPD52L2 in SMMC-7721 cells.

Figure 1.

Lentivirus infection and knockdown efficiency of SMMC-7721 cells. A: Bright field and fluorescence photomicrographs after transduction of SMMC-7721 cells in Con, shCon and shTPD52L2 groups respectively. Over 80% of cells were infected with lentivirus by visualized GFP expression. Scale bar: 100 µm. B: Relative expression level of TPD52L2 in SMMC-7721 cells with quantitative PCR. **P < 0.01, compared to shCon. C: Western blot analysis of TPD52L2 to present a satisfying knockdown efficiency.

Depletion of TPD52L2 repressed cell proliferation of SMMC-7721

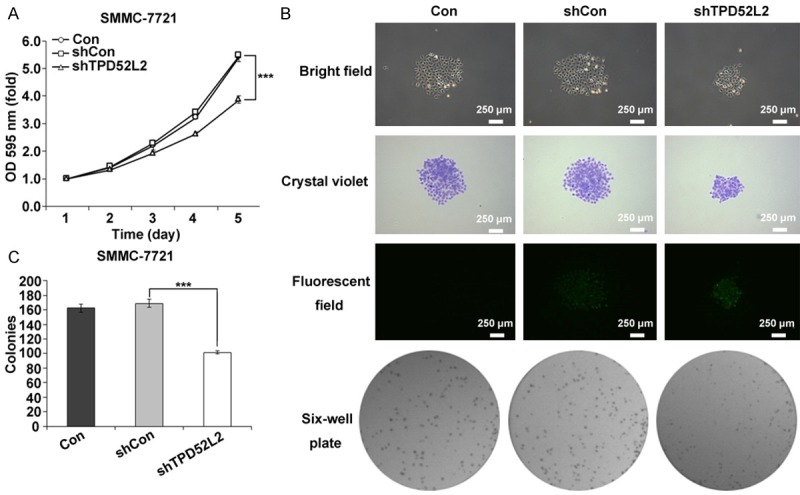

Deregulated cell growth can be found in most malignancy cancers and is regarded as an important characteristic of cancer. The effect of TPD52L2 knockdown on the proliferation of SMMC-7721 cells was monitored daily by MTT assay for 5 days. Line chart in Figure 2A indicated that non-silencing cells had no obvious difference from control cells (shCon vs. Con), meanwhile comparing to non-infected cells, a statically significant inhibition was observed in day 5 (shTPD52L2 vs. Con, P < 0.001), suggesting that knockdown of TPD52L2 led to repressed cancer cell proliferation.

Figure 2.

Colony formation ability and proliferation rate of SMMC-7721 cells with TPD52L2 silencing. A: Line chart of MTT assay by optical density at 595 nm of SMMC-7721 cells in Con, shCon and shTPD52L2 groups respectively. ***P < 0.001, compared to shCon. B: The colony formation of SMMC-7721 cells in Con, shCon and shTPD52L2 groups viewing under bright field, crystal violet, fluorescent field (Scale bar: 250 µm), and six-well plate respectively. C: The statistical analysis of colony numbers in Con, shCon and shTPD52L2 groups. ***P < 0.001, compared to shCon.

Colony formation is a hallmark of malignancy of cancer cells in vitro [23]. It was surprisingly noticeable that down-regulation of TPD52L2 significantly suppressed colony formation capability of SMMC-7721 cells (Figure 2B and 2C). The colony was remarkably smaller and colony numbers were statistically fewer than control cells (shTDP52L2 vs. shCon, P < 0.001). Collectively, knockdown of TPD52L2 by RNAi could markedly suppress the proliferation and colony formation ability of SMMC-7721 cells.

TPD52L2 silencing induced cell cycle arrest

To ascertain us whether the decreased cell proliferation induced by knockdown of TPD52L2 is due to cell cycle arrest, we performed FACS assay to determine the cell cycle distribution. Figure 3 revealed that the G0/G1-phase DNA content in TPD52L2-silencing cells (68.44%) was significantly higher than that in non-silencing cells (59.43%, P < 0.001), indicating the cell cycle of TPD52L2-silencing cells was arrested in the G0/G1 phase. These findings are in agreement with cell growth inhibition, which suggest TPD52L2 could modulate SMMC-7721 cell growth via cell cycle control.

Figure 3.

Depletion of TPD52L2 triggered G0/G1 cell cycle arrest. A: Cell cycle distribution of SMMC-7721 cells by flow cytometry in Con, shCon and shTPD52L2 groups respectively. B: Cell population under different stages of G0/G1, S, G2/M phase. ***P < 0.001, compared to shCon. C: Variant distribution of SMMC-7721 cells of Con, shCon, and shTPD52L2 in sub-G1 phase. **P < 0.01, compared to shCon.

To have further elucidation in the cell cycle arrest, we analyzed the population of sub-G1 class in the infected SMMC-7721 cells. Significant accumulation of sub-G1 group (Figure 3C) indicated apoptosis was processing when TPD52L2 was absent. This observation is in agreement with cell proliferation study and colony formation reduction.

Discussion

RNAi has been employed as an efficient therapeutic tool against human malignancy carcinomas in recent decades [24-26], and lentivirus is the most ideal vehicle for gene transduction and integration [27] with a lower immunogenicity, decreased likelihood of insertion mutagenesis, and efficient infection to both primary and non-dividing cells [28,29]. In this study we identified and functionally characterized the potential therapeutic value of knocking down TPD52L2 gene in human liver cancer with SMMC-7721 as model cells. We demonstrated that downregulated TPD52L2 expression level resulted in attenuated cell proliferation and colony formation. Cell cycle arrest and suggestive apoptosis were also verified.

TPD52 is overexpressed in high-grade serous carcinomas relative to borderline tumors. There was evidence that TPD52 might promote invasion through solid tissues, as suggested from a fact that injection with TPD52-expressing 3T3 cells formed lung metastasis in immunocompetent mammalian hosts [30]. It is interesting that our findings are in consistent with the report from Lewis et al. [30], and we provided further supportive demonstration of TPD52L2 (or hD54) depletion could remarkably suppress the tumorigenesis of cancer cell. It’s been reported that some genes playing roles in preventing tumor formation and metastasis were down-regulated in TPD52-expressing cells, including caveolin [31], the cadherin gene family [32], and the anti-angiogenesis gene thrombospondin22 [33]. Members of TPD52 are involved in protein-protein interactions [34-36]; Annexin syntaxin I [37], MAL2 [36] and VAMP2 [38] have been reported to be TPD52 interacting partners. Nowadays the biological function role of TPD52L2 via cell cycle control has yet to be elucidated, therefore we will put focus on signaling pathways for next step to elucidate the molecular mechanism of silencing TPD52L2 leading to suppressed cancer cell proliferation.

In summary, our findings indicated that TPD52L2 played an important role in cancer cell proliferation and cell cycle regulation in liver cancer, and depletion of TPD52L2 could trigger cell cycle arrest and cell apoptosis. It was surprising to notice an efficient blocking in cancer cell colony formation, which indicated TPD52L2 was critical for liver carcinoma tumorigenesis. Our studies revealed TPD52L2 could be a novel therapeutic target for human liver cancer and it deserves further study including molecular mechanism.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for the support of the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (grant no. 12ZZ077).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Barker-Collo S, Bartels DH, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bhalla K, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Boufous S, Bucello C, Burch M, Burney P, Carapetis J, Chen H, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahodwala N, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ezzati M, Feigin V, Flaxman AD, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Franklin R, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gonzalez-Medina D, Halasa YA, Haring D, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Hoen B, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Keren A, Khoo JP, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Ohno SL, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Mallinger L, March L, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGrath J, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Michaud C, Miller M, Miller TR, Mock C, Mocumbi AO, Mokdad AA, Moran A, Mulholland K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KM, Nasseri K, Norman P, O’Donnell M, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Phillips D, Pierce K, Pope CA 3rd, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Raju M, Ranganathan D, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Rivara FP, Roberts T, De Leon FR, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Segui-Gomez M, Shepard DS, Singh D, Singleton J, Sliwa K, Smith E, Steer A, Taylor JA, Thomas B, Tleyjeh IM, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Undurraga EA, Venketasubramanian N, Vijayakumar L, Vos T, Wagner GR, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Wilkinson JD, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh PH, Yip P, Zabetian A, Zheng ZJ, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luke C, Price T, Roder D. Epidemiology of cancer of the liver and intrahepatic bile ducts in an Australian population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1479–1485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katanoda K, Matsuda T. Five-year relative survival rate of liver cancer in the USA, Europe and Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44:302–303. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li G, Xiao Z, Liu J, Li C, Li F, Chen Z. Cancer: a proteomic disease. Sci China Life Sci. 2011;54:403–408. doi: 10.1007/s11427-011-4163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng GQ, Zhang PF, Deng X, Yu FL, Li C, Xu Y, Yi H, Li MY, Hu R, Zuo JH, Li XH, Wan XX, Qu JQ, He QY, Li JH, Ye X, Chen Y, Li JY, Xiao ZQ. Identification of candidate biomarkers for early detection of human lung squamous cell cancer by quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111.013946. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne JA, Tomasetto C, Garnier JM, Rouyer N, Mattei MG, Bellocq JP, Rio MC, Basset P. A screening method to identify genes commonly overexpressed in carcinomas and the identification of a novel complementary DNA sequence. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2896–2903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SL, Maroulakou IG, Green JE, Romano-Spica V, Modi W, Lautenberger J, Bhat NK. Isolation and characterization of a novel gene expressed in multiple cancers. Oncogene. 1996;12:741–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu H, Lam DC, Han KC, Tin VP, Suen WS, Wang E, Lam WK, Cai WW, Chung LP, Wong MP. High resolution analysis of genomic aberrations by metaphase and array comparative genomic hybridization identifies candidate tumour genes in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2007;245:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang R, Xu J, Saramaki O, Visakorpi T, Sutherland WM, Zhou J, Sen B, Lim SD, Mabjeesh N, Amin M, Dong JT, Petros JA, Nelson PS, Marshall FF, Zhau HE, Chung LW. PrLZ, a novel prostate-specific and androgen-responsive gene of the TPD52 family, amplified in chromosome 8q21.1 and overexpressed in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1589–1594. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhanasekaran SM, Barrette TR, Ghosh D, Shah R, Varambally S, Kurachi K, Pienta KJ, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM. Delineation of prognostic biomarkers in prostate cancer. Nature. 2001;412:822–826. doi: 10.1038/35090585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin MA, Varambally S, Beroukhim R, Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Paris PL, Hofer MD, Storz-Schweizer M, Kuefer R, Fletcher JA, Hsi BL, Byrne JA, Pienta KJ, Collins C, Sellers WR, Chinnaiyan AM. Overexpression, amplification, and androgen regulation of TPD52 in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3814–3822. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malek RL, Irby RB, Guo QM, Lee K, Wong S, He M, Tsai J, Frank B, Liu ET, Quackenbush J, Jove R, Yeatman TJ, Lee NH. Identification of Src transformation fingerprint in human colon cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21:7256–7265. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrne JA, Balleine RL, Schoenberg Fejzo M, Mercieca J, Chiew YE, Livnat Y, St Heaps L, Peters GB, Byth K, Karlan BY, Slamon DJ, Harnett P, Defazio A. Tumor protein D52 (TPD52) is overexpressed and a gene amplification target in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:1049–1054. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrne JA, Mattei MG, Basset P. Definition of the tumor protein D52 (TPD52) gene family through cloning of D52 homologues in human (hD53) and mouse (mD52) Genomics. 1996;35:523–532. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne JA, Mattei MG, Basset P, Gunning P. Identification and in situ hybridization mapping of a mouse Tpd52l1 (D53) orthologue to chromosome 10A4-B2. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1998;81:199–201. doi: 10.1159/000015029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrne JA, Nourse CR, Basset P, Gunning P. Identification of homo- and heteromeric interactions between members of the breast carcinoma-associated D52 protein family using the yeast two-hybrid system. Oncogene. 1998;16:873–881. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nourse CR, Mattei MG, Gunning P, Byrne JA. Cloning of a third member of the D52 gene family indicates alternative coding sequence usage in D52-like transcripts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1443:155–168. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Q, Chen J, Zhu L, Liu Y, Zhou Z, Sha J, Wang S, Li J. A testis-specific and testis developmentally regulated tumor protein D52 (TPD52)-like protein TPD52L3/hD55 interacts with TPD52 family proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okoli AS, Raftery MJ, Mendz GL. Comparison of Helicobacter bilis-Associated Protein Expression in Huh7 Cells Harbouring HCV Replicon and in Replicon-Cured Cells. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:501671. doi: 10.1155/2012/501671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim DH, Behlke MA, Rose SD, Chang MS, Choi S, Rossi JJ. Synthetic dsRNA Dicer substrates enhance RNAi potency and efficacy. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:222–226. doi: 10.1038/nbt1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo W, Zhang Y, Chen T, Wang Y, Xue J, Zhang Y, Xiao W, Mo X, Lu Y. Efficacy of RNAi targeting of pyruvate kinase M2 combined with cisplatin in a lung cancer model. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0860-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park CH, Bergsagel DE, McCulloch EA. Mouse myeloma tumor stem cells: a primary cell culture assay. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1971;46:411–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seyhan AA. RNAi: a potential new class of therapeutic for human genetic disease. Hum Genet. 2011;130:583–605. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyner J, Druker BJ. RNAi screen for therapeutic target in leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Micklem DR, Lorens JB. RNAi screening for therapeutic targets in human malignancies. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2007;8:337–343. doi: 10.2174/138920107783018426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimm D, Kay MA. RNAi and gene therapy: a mutual attraction. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007:473–481. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huszthy PC, Giroglou T, Tsinkalovsky O, Euskirchen P, Skaftnesmo KO, Bjerkvig R, von Laer D, Miletic H. Remission of invasive, cancer stem-like glioblastoma xenografts using lentiviral vector-mediated suicide gene therapy. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zufferey R, Dull T, Mandel RJ, Bukovsky A, Quiroz D, Naldini L, Trono D. Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J Virol. 1998;72:9873–9880. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9873-9880.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis JD, Payton LA, Whitford JG, Byrne JA, Smith DI, Yang L, Bright RK. Induction of tumorigenesis and metastasis by the murine orthologue of tumor protein D52. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:133–144. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carver LA, Schnitzer JE. Caveolae: mining little caves for new cancer targets. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:571–581. doi: 10.1038/nrc1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behrens J. Cadherins and catenins: role in signal transduction and tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1999;18:15–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1006200102166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawler J, Detmar M. Tumor progression: the effects of thrombospondin-1 and -2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boutros R, Bailey AM, Wilson SH, Byrne JA. Alternative splicing as a mechanism for regulating 14-3-3 binding: interactions between hD53 (TPD52L1) and 14-3-3 proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:675–687. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00944-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sathasivam P, Bailey AM, Crossley M, Byrne JA. The role of the coiled-coil motif in interactions mediated by TPD52. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:56–61. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson SH, Bailey AM, Nourse CR, Mattei MG, Byrne JA. Identification of MAL2, a novel member of the mal proteolipid family, though interactions with TPD52-like proteins in the yeast two-hybrid system. Genomics. 2001;76:81–88. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas DD, Kaspar KM, Taft WB, Weng N, Rodenkirch LA, Groblewski GE. Identification of annexin VI as a Ca2+-sensitive CRHSP-28-binding protein in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35496–35502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proux-Gillardeaux V, Galli T, Callebaut I, Mikhailik A, Calothy G, Marx M. D53 is a novel endosomal SNARE-binding protein that enhances interaction of syntaxin 1 with the synaptobrevin 2 complex in vitro. Biochem J. 2003;370:213–221. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]