Abstract

Latino families face multiple stressors associated with adjusting to United States mainstream culture that, along with poverty and residence in inner-city communities, may further predispose their children to risk for negative developmental outcomes. Evidence-based mental health treatments may require culturally informed modifications to best address the unique needs of the Latino population, yet few empirical studies have assessed these cultural elements. The current study examined cultural values of 48 Dominican and Mexican mothers of preschoolers through focus groups in which they described their core values as related to their parenting role. Results showed that respeto, family and religion were the most important values that mothers sought to transmit to their children. Respeto is manifested in several domains, including obedience to authority, deference, decorum, and public behavior. The authors describe the socialization messages that Latina mothers use to teach their children respeto and present a culturally derived framework of how these messages may relate to child development. The authors discuss how findings may inform the cultural adaptation of evidence-based mental health treatments such as parent training programs.

Keywords: Latino parenting, socialization, cultural values, respeto, preschoolers

Mental health interventions for the Latino population are of considerable interest as researchers tackle issues such as high rates of youth violence, substance use, depression, and academic failure among Latino youth (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Henry, & Florsheim, 2000; Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2002). Given a lack of empirical data, however, questions regarding the efficacy of evidence-based treatments (EBTs) with Latinos and other ethnic minority populations remain unresolved. Based on the relatively few studies that have included diverse populations, one meta-analytic study concluded that EBTs are likely to be appropriate and efficacious with ethnic minority individuals (Miranda, Bernal, Lau, Kohn, Hwang, & LaFramboise, 2005). On the other hand, a meta-analysis comparing EBTs with culturally adapted programs found the latter to be superior in terms of effect sizes on target outcomes (Griner & Smith, 2006). The dearth of studies addressing this issue, along with the inconsistent findings emerging from the field, has stimulated a debate surrounding cultural adaptation research.

Proponents of cultural adaptation, or the process of modifying EBTs to incorporate aspects of culture, argue that such modifications are necessary to increase the transportability of treatments to ethnic minority populations. Findings that ethnic minority populations underutilize mental health services (e.g., Garland, Lau, Yeh, McCable, Hough, & Landsverk, 2005) bolster this argument. According to critics, though, cultural adaptations risk compromising key ingredients and therefore reducing the efficacy of EBTs. In their review of parenting intervention programs adapted for Latino populations, Dumka and colleagues (2002) found that few had been guided by empirical research. Moreover, cultural adaptations come at great cost. Given the multiple and complex issues surrounding the provision of mental health interventions for ethnic minority populations, scholars have recommended a focus on “the articulation and documentation of how ethnicity and culture play a role in the treatment process and how intervention may need to be adapted or tailored to meet the needs of diverse families” (Bernal, 2006, p.144). Following suit, the present study documents how a central cultural value (i.e., respeto) of two Latino subgroups (Mexicans and Dominicans) relates to parenting, which has direct implications for parent training programs as a widely used EBT.

Ethnic Socialization

The process through which parents transmit cultural values, as well as beliefs, traditions and behavioral norms, to their children is referred to as ethnic-racial socialization (Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006). Of interest to the present study are the ethnic-racial socialization messages that focus on the values and behaviors unique to a particular group and that serve to promote the behavioral competence of children within their own culture of origin. Only a handful of researchers have examined ethnic-racial socialization in Latino families. Qualitative data suggests that Puerto Rican and Mexican mothers purposefully engage in ethnic-racial socialization, a process they view as highly important (Umaña-Taylor & Yazedijan, 2006). Quantitative data supports these findings by showing that the majority of Puerto Rican and Dominican families report using strategies of ethnic-racial socialization with their school-aged and adolescent children and that messages are mostly likely to center around cultural heritage as a means of preserving cultural values and norms (Hughes, 2003). Moreover, socialization practices have been found to influence the ethnic identity and ethnic behaviors of Mexican American school-age children (Knight, Bernal, Garza, Cota, & Ocampo, 1993).

The broader ethnic-racial socialization literature with African American and immigrant families has advanced even further in ways that may contribute to our understanding of Latinos. Most notably, there is growing evidence that socialization practices are associated in important ways with child outcomes. A recent review of the literature (Hughes et al., 2006) suggests that children’s academic achievement and psychological functioning, including internalizing (e.g., depression) and externalizing (e.g., conduct problems) behaviors, relate to the messages that parents use to teach their children about race and ethnicity. For example, studies with African American families show that ethnic-racial socialization is positively related to cognitive functioning and negatively related to behavior problems in preschool and first grade children (with important moderation effects by gender and neighborhood characteristics for first graders; Caughy, Nettles, O’Campo, & Lohrfink, 2006; Caughy, O’Campo, Randolph, & Nickerson, 2002). These findings suggest that the efficacy of EBTs such as parent training programs may be limited for ethnic minority families to the extent that they rely exclusively on Westernized models of parenting and fail to consider culture.

Cultural Values

For several decades, cross-cultural researchers have urged that we step away from Westernized models of parenting that may mask critical Latino parenting practices (Baumrind, 1995; Bornstein & Cote, 2003; Levine, 1977; Moreno, 2002) and adopt an emic (within culture) framework that allows important concepts to emerge from the “bottom-up,” directly from the population of interest. Emic studies may yield a more complete understanding of Latino parenting and provide information relevant to the adaptation of Latino families to a new social reality (i.e., that of functioning within U.S. mainstream society; Baca Zinn, 1982; Zayas & Rojas-Flores, 2002). The ethnic-racial socialization literature exemplifies the utility and further need of this approach.

With some exception, the developmental literature has been slow in adopting an emic approach to advance our understanding of core cultural concepts relevant to the study of Latino families (Zayas & Rojas-Flores, 2002). The work of Suarez-Orozco and colleagues has demonstrated the richness of data that emerges from large-scale ethnographies by highlighting, for instance, the issue of separation and reunification of immigrant children and their parents (Suarez-Orozco, Todorova, & Louie, 2002). Smaller qualitative studies have explored cultural values among Latinos, illustrating that Mexican and Puerto Rican mothers value obedience and respect more than European American values such as independence, autonomy and being assertive (Alvy, 1994; Arcia & Johnson, 1998; Delgado-Gaitan, 1994; Gonzalez-Ramos, Zayas, & Cohen, 1998). Scholars have argued that such cultural values and their associated behavioral norms characterize the psychological experience of ethnic group membership (Phinney, 1996).

The cultural value of respeto (Gonzales-Ramos et al., 1998) emphasizes obedience and dictates that children should be highly considerate of adults and should not interrupt or argue (Delgado-Gaitan, 1994). More generally, respeto relates to “knowing the level of courtesy and decorum required in a given situation in relation to other people of a particular age, sex and social status” (Harwood, Miller, & Irizarry, 1995, p. 98) and ultimately serves as a means of maintaining harmony within the extended family (Marin & Marin, 1991). In a series of cross-cultural studies, Harwood and colleagues found that Puerto Rican mothers of infants attended more to dimensions of respect (e.g., obedience, good behavior) than personal development (e.g., self-confidence, independence), discouraged their children’s autonomous and exploratory behaviors, asserted their parental authority, and used direct interventions like physical restraint more than European American mothers, who used more modeling, praise and suggestions (Harwood, 1992; Harwood, Schoelmerich, Schulze, & Gonzalez, 1999). At least in the context of parenting young children, respeto appears to delineate the boundaries of appropriate and inappropriate child behavior and to be an important determinant of parenting practices. A next step is to look beyond the infancy and toddler years to explore the specific behavioral manifestations of respeto and the practices that Latino parents use to socialize their children to be respectful.

The Present Study

The present study used a qualitative research approach to study the cultural values of Latina mothers of young children. In light of the considerable heterogeneity in the Latino population, we focused on two subgroups of Latinos: Mexican and Dominican. We selected these groups because they represent the largest and the largest growing groups, respectively, in the U.S. Specific questions addressed by this study were: (1) What are the primary cultural values for Latina mothers of young children?; (2) How do Latina mothers view their cultural values in relation to mainstream U.S. American values?; (3) Assuming that respeto is a primary Latino value: (a) How is respeto manifested in young children?; (b) How do Latino parents socialize their children to show respeto?; and (c) How does respeto change with generational status, given past findings that values and parenting practices change with time and acculturation (Dumka, Roosa, & Jackson, 1997; Gonzalez-Ramos, Zayas, & Cohen, 1998; Harrison, Wilson, Pine, Chan, & Buriel, 1990; Planos, Zayas, & Busch-Rossnagel, 1995).

The ultimate aim of the present study was to use the findings on respeto to derive a culturally informed model of Latino parenting that goes beyond parenting practices/styles to incorporate cultural socialization messages. This model would reflect the way in which parents socialize children to follow culturally bound expectations of behavior and serve as a heuristic to enrich our knowledge of the relation between parenting and child development in Latino families. In this way, we may begin to understand cultural aspects (e.g., culturally specific socialization messages) related to family functioning and whether and in what ways EBTs such as parent training programs must be adapted for Latino populations.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were 48 female primary caregivers of 3- to 6-year-old children residing in a large Northeastern city who self-identified as Dominican (n = 31) or Mexican (n = 17). Given that demographic variables differed notably between Mexican, Dominican-born, and U.S.-born Dominican mother, statistics for each group are reported separately. Results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Focus Group Participants

| Immigrant Mexicana N = 17 |

Immigrant Dominicanb N = 24 |

U.S.-born Dominicanc N = 7 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Mother’s age | 31.47 (5.66) | 35.26 (9.47) | 28.71 (4.82) |

| Household income ($) | 17,496 (6,641) | 15,794 (7,746) | 33,588 (18,500) |

| AMAS: U.S. American identity1 | 2.59 (.88) | 2.92 (.88) | 3.81 (.50) |

| AMAS: Ethnic identity | 3.94 (.12) | 3.82 (.35) | 3.89 (.18) |

| AMAS: English language competence3 | 1.88 (.59) | 2.55 (.84) | 3.92 (.21) |

| AMAS: Spanish language competence | 3.93 (.15) | 3.72 (.47) | 3.54 (.81) |

| AMAS: U.S. American cultural knowledge3 | 1.87 (.40) | 2.46 (.72) | 3.12 (.49) |

| AMAS: Ethnic cultural knowledge1,2 | 3.18 (.54) | 3.06 (.68) | 2.29 (.63) |

| Frequencies (%) | |||

| Mother’s educational status3 | |||

| Less than high school | 47% | 21% | 0 |

| High school | 30% | 13% | 14% |

| More than high school | 23% | 66% | 86% |

| Mother’s occupational status (employed for pay)3 | 12% | 38% | 43% |

| Mother’s language preference (Spanish)3 | 100% | 71% | 44% |

Note. AMAS = Abbreviated Multicultural Acculturation Scale.

Differences between Groups a and c.

Differences between Groups b and c.

Differences between all groups.

Mexican mothers

All Mexican participants were born in Mexico and had been residing less than 10 years, on average, in the U.S. All preferred to speak Spanish in the home. The majority (82%) of the Mexican mothers were married to or living with the biological father of the preschool-aged child. Most mothers did not work outside the home (88%) and almost half (47%) had not completed high school. Mean yearly household income was approximately $17,500. All Mexican participants were the biological mother of the preschool-aged child. Mothers were 31 years old (SD = 5.66) on average.

Foreign-born Dominican mothers

The majority (77%; n = 24) of the Dominican mothers were foreign-born and had been residing in the U.S. for an average of 15 years. Among immigrant Dominican mothers, most (71%) preferred to speak Spanish at home, although several (17%) preferred English and the rest (12%) had equal preference. About half (42%) of these mothers were married or living with a partner. The majority (63%) of immigrant Dominican mothers did not work outside the home, and most (63%) had at least some college, although 21% did not complete high school. The mean yearly income was less than $16,000. Most (n = 20) participants in this subsample were biological mothers, and four were grandmothers who were the primary caregiver for the preschooler. The mean age for this subsample was 35 years (SD = 9.47).

U.S.-born Dominican mothers

Seven Dominican mothers were born in the U.S. Approximately half of the mothers in this subgroup preferred to speak Spanish and the other half preferred to speak English in the home. Four mothers (57%) reported being married or living with a partner. Forty-three percent of the mothers worked for pay outside the home. All had completed high school or its equivalent, and the majority (86%) had completed some years of college education. The average household income was $33,600. All U.S.-born Dominican participants were the biological mothers of the preschooler. Mothers’ average age was 28 years (SD = 4.82).

Measures

Participants completed a demographic form on their age, place of birth, length of residence in the U.S., family composition, child’s age, education, occupation, and household income. In addition, participants completed the Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale (AMAS, Zea, Asner-Self, Birman, & Buki, 2003). The AMAS is a measure of cultural adaptation that can be used with any ethnic group. The AMAS taps into cultural competence and identity; cultural competence refers to the individual’s knowledge of the culture as well as his or her ability to function competently within it. Specific domains measured by the AMAS are cultural knowledge, language use and identity. All domains are measured for both the culture of origin (enculturation) and mainstream/“U.S. American” culture (acculturation), allowing for an examination of cultural adaptation as a bidimensional construct. The AMAS was standardized in English and Spanish with Latino university students from various countries of origin and showed adequate psychometric properties (Zea et al., 2003).

Procedure

Participants were recruited with fliers and in person at Head Start and day care centers in a large Northeastern city. All Mexican participants came from one center, Spanish-speaking Dominican participants came from another center, and English-speaking Dominican participants came from a third center. Focus groups were conducted in the mother’s language of choice at her respective childcare center. Two focus groups of Spanish-speaking Dominican mothers, two focus groups of English-speaking Dominican mothers, and two focus groups of Spanish-speaking Mexican mothers were held. We were not able to identify any English-speaking Mexican mothers for participation in the study. Focus groups were conducted until the information provided by the informants reached saturation or was redundant with that provided from earlier groups.

Each focus group lasted approximately 2 hours and was led by the first author and a research assistant (both bilingual). Participants were paid $25 for participation and childcare was provided. After obtaining informed consent verbally and in writing, mothers completed the demographic form and AMAS in their preferred language. To address the possible limitations of limited functional literacy, forms were administered in 10-min face-to-face individual interviews for all participants. Additional bilingual research staff assisted with these interviews. A videotaped 110-min group discussion followed. This focus group followed a semistructured protocol with questions that addressed: (1) the identification of Latino values, (2) the identification of mainstream American values, and (3) the definition and socialization of respeto.

Focus groups began with open-ended questions about cultural values in general (i.e., What values are most important to you as a Dominican/Mexican?), and proceeded to narrow in on respeto (e.g., What does it mean for a child to show respeto? What would a preschooler who is showing respeto be doing?). Mothers were asked to provide specific behavioral examples of respeto and to discuss how they teach young children respeto and the situations in which respeto may be more (or less) important. Focus group discussions were videotaped and transcribed by an independently contracted transcriber. There were 150 pages of transcription that resulted from the four focus groups (note that audio was lost on the last two focus groups and detailed notes were used in lieu of transcripts for these two focus groups). All study activities were approved by the IRB.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted by the first and second authors, with consultation from the third author; all three coders are bilingual. Transcripts were coded in their original language (i.e., Spanish or English). Coding followed a constant comparative analysis approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Padgett, 1998), in which the data was analyzed for themes, which were then confirmed by further analysis of the data, followed by a third review of the data to look for new codes. A set of codes was developed a priori based on the focus group questions and aims of the study. Coders read transcripts independently and discussed the data after each round of analysis to reach consensus. Codes were then refined based on the data and through consensus; in this way, we achieved agreement between coders. Twelve codes—both anticipated and unanticipated—were identified. Each focus group was coded separately and results from the six groups were examined independently and in concert. No software was used.

For the present study, a subset of codes was used, as described below. Latino Values: any value described as characteristic of the Mexican or Dominican culture. U.S. American Values: any value described as characteristic of mainstream U.S. American (i.e., European American; heretofore referred to as “American”) culture. Respeto—Behavioral manifestation: any description of what a child who is showing respeto would be doing or saying.

Falta de respeto—Behavioral manifestation: any description of what a child who is not showing respeto would be doing or saying. Respeto—Situational Cues: any description of a situation in which a child should show respeto. Teaching of respeto: how and at what age mothers teach their children respeto. Generational shifts in respeto: Changes in how respeto manifested a generation ago, when participants were being raised (often outside of the U.S.) and during the current generation, when participants are raising their own children in the U.S.

Results

First, we examined the AMAS for each subgroup (see Table 1). All participants were highly enculturated, whereas acculturation levels varied by subgroup. More specifically, Mexican mothers reported a high level of enculturation and a low level of acculturation. Similarly, immigrant Dominican mothers reported a high level of enculturation, particularly in terms of identity and language, and moderately low acculturation. In contrast, U.S.-born Dominican mothers were highly acculturated and highly enculturated. Given differences in the cultural adaptation (and demographic profiles) of Mexican mothers, U.S.-born Dominican and immigrant Dominican mothers, we were particularly cognizant of potential subgroup differences in the qualitative data. Somewhat surprisingly, there were no differences in themes or codes based on ethnicity or language (although some minor interesting differences emerged, as noted below). Results were combined and are presented for the six focus groups as a whole.

Core Latino Values

Our first aim was to identify important values for Latina mothers of young children. The most salient cultural values for Mexican and Dominican mothers were familia, religion, and respeto. As stated by a Dominican mother, “The most important thing is that they (children) have values and that those values be that they respect their parents, respect others.” The importance of religion (“that children keep the commitment of going to church”) was brought up by Dominican and Mexican mothers but was particularly emphasized by Mexican mothers, who spoke of their veneration of the Virgin Mary and of the Virgen de Guadalupe. A focus on family (i.e., familismo) was evident across the groups, with extended family serving a primary role in providing social and emotional support. For example, one Dominican mother stated, “We value very much the family. We are a group that in raising a family, we want for us to always be united, that whatever problem arises, one always goes to the family. We will resolve it.” Similarly, a Mexican mother said, “The notion that we be … united, helping each other, starts with family. Family includes nephews, cousins, uncles. If one can help, one helps them with what one can. That is something that we inculcate in our children, that it is a family.” Beyond family as a support system, mothers talked about family living and spending time together; “Latinos, Dominicans, Mexicans, we have the custom that we are all there. Out of necessity or for one reason or another, we live five (family members) in a two bedroom apartment. In the Dominican Republic, if we have a house, we live 10 family members in that house.” To which another mother responded, “And if the house has a large yard, the mother will say ‘Make your little house here. Make your little house there.’ And in the yard we live; we fill it up (with family houses)!”

In addition to the values of respeto, familia, and religion, mothers reported on the importance of maintaining their culture (i.e., “that we not forget our Mexican culture”), which was clearly tied to the experience of raising their children outside of their country of origin. A Dominican mother expressed the wish, “That they remember, even though they are in a different country from the one where their mother and grandmother was raised and that they were born and raised here (in the U.S.), that they remember where they came from.” Mothers were aware of the risk of loss of culture and teach their children to “fight for their culture” and remember their language (“not lose the language … the Spanish”) of origin. Toward this mean, mothers wanted to preserve aspects of their own upbringing in raising their children: “Well, for me, I’d like to raise my children how my mother raised me.”

Perceptions of U.S. American Values

Given the mainstream cultural context in which Latina mothers are raising their children, our next aim was to explore Dominican and Mexican mothers’ views of American values. When asked to discuss American values, Spanish-speaking mothers (85% of the sample) did so with the express caveat that they had few personal in-depth experiences with American families. Limited contact with Americans was more characteristic of Mexican mothers. Dominican mothers seemed to have more knowledge (both personal and indirect) of American culture and gave more elaborated responses to questions regarding American cultural values. Notably, though, both Dominicans and Mexicans expressed similar views of mainstream culture.

The American values observed by Dominican and Mexican mothers are that Americans are more independent (“Americans give their children independence. They let them do what they want.”), liberal in their thinking (“they have their minds open”) and more child-centric. For example, American mothers appear to spend more time (“Kind of like they dedicate more time to their children.”), communicate more frequently and openly (“The value of giving children a say in matters is very American.”), and concentrate on teaching activities (”they make time to explain things [to their children].”) more with their children. One mother summarized the American approach to parenting by saying, “When [children] are little … they start showing them to open their own wings, so to speak, so that they will take care of themselves.” In contrast, Dominican and Mexican mothers view themselves as less able to grant independence (“The American culture grants more independence to children. Us [Latinos], with our children, I think not. Because I think that as soon as we have children, we stick close to them.”) or communicate openly with their children (“But among us Hispanics, its a little more difficult for a child to express himself.”).

In addition, mothers viewed American families as achievement oriented: “I think that what they focus most on in this country is to achieve a high economic status. They don’t believe in mediocrity. They want to be at the maximum (level).” Mothers viewed this achievement orientation as inconsistent with a familistic orientation, because career is seen as a priority over family. One mother noted that Americans: “take charge of their lives … of their career, and later, if possible, well then they get married.” Another stated, “I don’t think that they value family very much. Because most Americans, when their children are 18 years old, they throw them out, most of them. They say, ‘Go study and do what you want to do and that’s it. I’ve taken care of you until now that you are 18 and now you leave.’” Similarly, adult American children are seen as, “not in touch with the needs of their parents.”

Respeto

Respeto was the primary focus of the present study and following a validation of its importance, we aimed to explore (1) the ways in which it manifests for young children and (2) socialization of this value. In response to the question, “What are your values as Dominicans/Mexicans?” respeto was mentioned first or second in every focus group, indicating its centrality and salience for Dominican and Mexican mothers. Respeto was described as the foundation for successful child development; “We try always to given them all that information (i.e., how to be respectful) so that they can be better raised and be good with one another.” For mothers, it is the primary focus of child rearing, as revealed by this statement from a Dominican mother: “One struggles so much to inculcate in them that respect of behaving well, of listening to their elders, of listening to their parents when we speak to them. That is the ultimate goal.”

Behavioral Manifestations of Respeto

To understand the behavioral manifestations of respeto, mothers were asked to describe in detail what a respectful or disrespectful preschooler would be doing or saying. We categorized the behavioral manifestations described by the mothers into four subdomains: obedience; deference; decorum; and public behavior. Obedience, or conformity to authority, refers to the importance of following commands and accepting rules without question. Deference refers to the courtesy owed to elders and reflects the hierarchical aspect of respeto. Elders, particularly grandparents, are afforded special status. One mother summed up this notion when she said, “Your parents are ‘number one.’ Your grandparents are even greater than ‘number one.’” Decorum dictates the appropriate behaviors for social interactions, particularly in more formalized situations. Children are expected to, “Say good morning, say please, use their manners, say good night, greet others formally.” Finally, public behavior refers to the set of boundaries imposed on the behavioral expression of children in public situations. Children must present well to others, particularly in public (“In public is when one [a parent] wants them [children] to be most respectful.”), perhaps because children are seen as a reflection of the entire family. Table 2 presents specific behavioral examples for each subdomain of respeto.

Table 2.

Behavioral Manifestations of Respeto

| Obedience/conformity to authority | |

| Obey parents no matter what | “If he doesn’t obey or did something wrong, then that is a lack of respect.” |

| Accept parental authority without questioning it | “You are very fresh. You cannot be disrespectful to your elders. I have told you, one hundred times I have told you, that when an elder tells you to go home, or tells you that your behavior is wrong, you pay attention and stay quiet and don’t make an ugly face because you are not big. Remember your place because you are a child and children have to respect adults.” |

| Look parent in the eye during commands | “When a child and a parent are talking, we must look each other in the eye.” |

| Stay quiet when reprimanded/disciplined | “My mother, if she reprimands me, I don’t answer. I stay quiet.” “My son, when he misbehaves to a certain point, I tell him, ‘Go to your room,’ [He responds] ‘But mommy, let me say something’ and I say, ‘No, you will go right now.’” |

| Never talk back | “In regards to the children … some of us raise them like: ‘You don’t talk. You don’t respond.’” |

| Deference | |

| Never listen in on/participate in adult conversations | “So I would say to him, ‘Well, and you, who invited you into this discussion? That looks bad. That reflects poorly on you. It is bad manners to get involved in adult conversations.” |

| Never express disagreement with adults | “Sometimes [my] mom says something that I disagree with, and sometimes I’ll even wink my eye, and I say, ‘Well, ok.’ Even though I disagree, to not be contrary, to not raise my voice, to not … do you understand?” |

| Never interrupt adults | “They [children] should not sit down and say, ‘Excuse me, mom, I need to talk to you.’ Because one is discussing adult matters that they are not supposed to listen to.” |

| Offer seat to elders | |

| Wait until all adults have a seat before sitting down | (Describing falta de respeto) “Nowadays, they [children] say hello and they sit down before you [the adult].” |

| Offer to help elders | “If my mother [child’s grandmother] needs something, that they [children] get it for her. They need to help her. They should not let her go get it.” |

| Defer to adult wishes | “If my child says, ‘Oh, I want to sleep with grandmother,’ No, quiet! She is the one who knows. If she is not feeling well, if she is sick or uncomfortable, you have to respect. And [I tell my] mother, ‘if he comes to you anyway, you get the belt and whip him two times.’” |

| Decorum | |

| Avoid bad words | “ … that the child not say bad words.” |

| Avoid rude tone of voice | “He comes and talks to me with an ugly tone, or to his grandparents, or his father, that is disrespect.” |

| Say please, thank you, etc. | “When his brother is playing with something and he comes and takes it. That is disrespectful. He needs to ask, ‘Can I play with you?’” |

| Greet adults politely (e.g., pedir la bendición) | “When you go out and someone greets you. Out of respect, you need to greet them.” “If an elder arrives at the house, you must greet them.” |

| Address elders formally (e.g., usted, Don/Doña rather than tu) | |

| Public behavior | |

| When visiting someone’s home, never touch anything without permission | “You need to ask permission to touch things … when we go out, don’t touch.” “To not respect things that belong to others. To me, that is disrespectful.” |

| Stay calm and quiet in public situations (e.g., visiting someone’s home) | (Referring to common saying) “Se ve mas bonito calladito./Quiet behavior looks nicer.” “For example, if one takes them somewhere … for example, this meeting that I took my son to; he knows that he has to be respectful with the people there. Behave well. Stay calm.” |

| Never run around noisily in nonsanctioned situations | “Stay seated. Not go around jumping all over the place.” |

Respeto in Context

More generally, respeto serves as the basis for mothers’ expectations of child behavior across all situations “with people you know and people you don’t know. It’s a rule that is imposed on one, wherever one may be.” Respeto is to be shown to all others, regardless of age or gender (i.e., “toward parents, grandparents, children, other people … everyone.”). Contrary to the traditional notion of respeto as strictly hierarchical (Harwood, Miller, & Irizarry, 1995), mothers described respeto as a broader construct in which respectful behavior toward peers is also important (“I always tell my children that you need to respect even the youngest children … show respect with everyone.”). This point was underscored when mothers were asked to select the one person toward whom children should show respect above all others; across the groups, mothers responded by explicitly naming: parents, grandparents, teachers, doctors, extended family members, and strangers. The data analysis revealed that participants across all focus groups agreed that they want their children to show respeto especially toward grandparents (“especially with elders”) and strangers (“In public is when one most wants them to have respect.”).

While showing respeto is paramount in interactions with everyone, the ways in which it should be demonstrated differs depending on the recipient. With parents, obedience is expected. Children must obey without question and accept discipline without argument. With elders, deference is expected. Particular attention should be paid to the needs and desires of elders. With peers, collectivistic social behavior is expected. Using someone’s toys without permission, refusing to share and fighting with peers were given as examples of disrespectful behaviors.

Teaching of Respeto

Asked to describe how children learn respeto, one mother replied, “They learn it because we inculcate it in them. There is no option. For the American, there is an option. But [not] for Hispanics … ” Others talked about the need for harsh parenting to ensure that children, being raised in today’s environment, learn respeto: “There are times when one has to smack [a child], especially now that children are so head-strong.” Notably, mothers were aware of alternate discipline practices such as loss of privileges but considered them, “soft.” Spanking, in contrast, is viewed as necessary in raising a child to behave well: “There comes a point when you have to spank [a child]. If one becomes soft or whatever, they will tantrum on you anywhere.” Most mothers agreed not only that spanking is a strategy that they rely on in raising respectful kids but also that they have been disempowered by U.S. societal views against spanking: “A child must be educated and taught how things are. Because if not, they will get the best of you. Because they are going to believe they are the parents, and it is not like that. Sometimes they’ll say, ‘No, because you can’t spank me, because you can’t punish me, I am going to take advantage of you.’ I don’t think that’s right. One has to raise and teach them as one was raised, with respect for parents.” A few mothers, however, noted that spanking was the wrong approach to teaching children respect and that Latino parents can learn from the American approach of punishing children by taking away privileges (“‘You’re not going to do this. I’m going to take this away.’ I think that’s better for my children.”).

Developmental considerations in the teaching of respeto

While socialization of respeto begins in early childhood, mothers’ expectations of respectful behavior and their tolerance of disrespectful behaviors are age-dependent. From a developmental perspective, children in the preschool years are just mastering the emotion and behavior regulation skills required to show respect. Mothers stated that 3-year-old children cannot be expected to act with respeto but by 4 and 5 years of age, children are believed to know right from wrong. “At 4 years old, he is a person that understands what is right and what is wrong. If he knows that what he is doing is wrong, then to me, that behavior is disrespectful.” During this age period, mothers believe, “if one already explained [what they did wrong] to them, and they do it again, that is disrespectful.” Although there was sound agreement regarding these age-related expectations, some mothers noted that the individual characteristics and particularly issues of developmental delays or behavioral problems (e.g., inattention or hyperactivity) need to be considered when determining whether common child-hood misbehaviors are considered disrespectful.

Generational Shifts in Respeto

Generational changes in how respeto manifests were described explicitly in each focus group. During their childhoods, participant mothers were taught strict and unquestioning obedience: “In the past, especially when my father disciplined me, [children] needed to lower their head and stay quiet.” Under no circumstances were children permitted to respond to parents who were setting limits or reprimanding them. In contrast, participant mothers believed that children should be able to express themselves more freely with their parents, though the manner in which they communicate must convey respeto. That is, if using a polite tone of voice and polite words, children may express disagreement or disappointment over a situation. As summarized by one mother, “we want respect but we also want communication.” Another mother believed that she would be showing her own child falta de respeto (i.e., a lack of respect) if she were to prohibit him from communicating openly to her (“because that would be a lack of respect on my part, to not listen to his needs”).

Interestingly, mothers believed that this shift in acceptable respectful behaviors was because of generational differences (“What was good about how our parents raised us, we will pass on to our children. What was bad, we will not pass on.”), rather than, for example, the influence of mainstream U.S. American cultural values. In addition, despite these apparent shifts away from traditional respeto, mothers continued to value obedience (i.e., one of the four subdomains of respeto) above all else. Children must obey: “because we are saying it, because Mom said so. That’s it.”

Discussion

The present study used focus groups to investigate the cultural values that are most salient to Dominican and Mexican mothers of preschoolers. Although several values are central to Latino cultures, findings from the present study suggest that respeto plays a predominant role in child rearing and underlies many of the practices of Dominican and Mexican mothers during the preschool years. Findings were consistent for immigrant Mexican, immigrant Dominican, and U.S.-born Dominican mothers, even in the presence of significant demographic and acculturation differences, suggesting that respeto is a pan-Latino cultural value. Future studies to examine respeto in other Latino subgroups and to determine in what ways respeto may shift according to acculturation would further inform our understanding of the heterogeneity of the Latino population and the adequate provision of EBTs (e.g., parent training) for this diverse population.

Past studies have highlighted the importance of respeto (Arcia & Johnson, 1998; Gonzalez-Ramos, Zayas, & Cohen, 1998; Harwood, 1992), and the present findings extend the literature by identifying four subdomains that capture the behavioral manifestations of this core value. Obedience refers to the expectation that children do as they are told without question. Deference refers to the courtesy owed to elders and people of high social status. Decorum dictates the appropriate behaviors for social interactions, particularly in more formalized situations. Public behavior refers to the set of boundaries imposed on the behavioral expression of children in public situations. In contrast, mainstream U.S. American socialization, in the view of Latina mothers, emphasizes independence, open communication and exploration. This notion of mainstream socialization reflects European American, middleclass values and is remarkably consistent with empirical findings (Harwood, 1992). Interestingly, despite the generally unacculturated status of the sample, participant mothers had a clear understanding of European American parenting and they expressed an appreciation for these mainstream values. Still, they viewed a focus on independence as inconsistent with Latino culture, with its focus on respeto.

These results compel us to move beyond Westernized frameworks (e.g., authoritarian, authoritative, permissive parenting; Baumrind, 1975) that do not emphasize the role of culture toward the development of new, culturally informed frameworks for the study of Latino parenting, as was the overarching aim of the present study. While respeto has long been emphasized as an important child rearing value in the literature on Latino family functioning (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002), it is not explicitly included in any current model of parenting. We propose a framework that recognizes respeto-driven parenting as an essential component of Latino parenting and ultimately, of Latino child functioning.

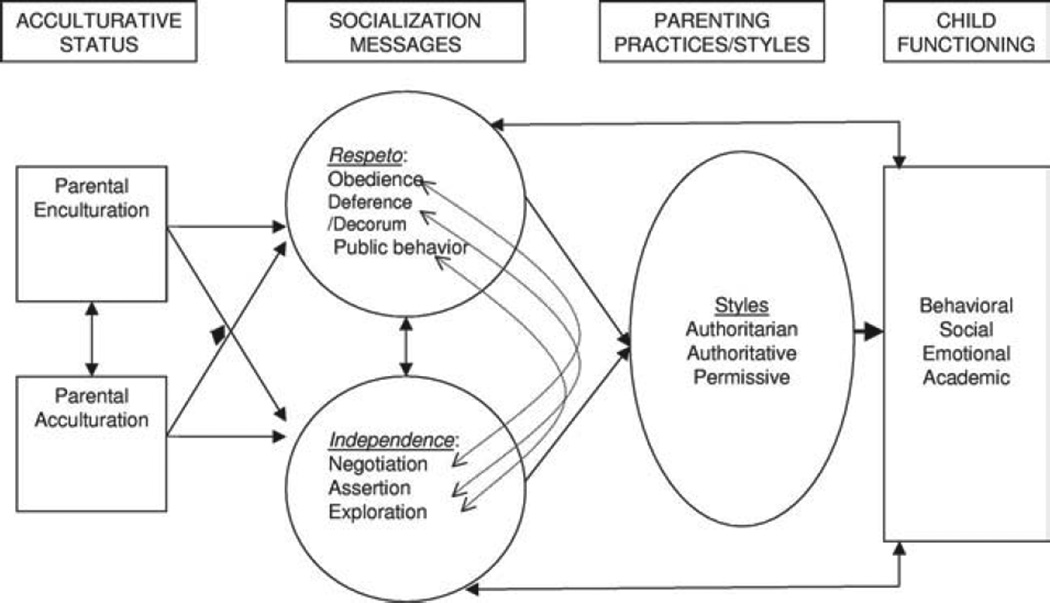

This culturally informed framework, presented in Figure 1, considers socialization messages rooted in the Latino culture, as well as those rooted in mainstream U.S. American culture, as important determinants of parenting practices/styles; both ultimately predict child functioning. To socialize Latino children in behaviors that reflect the cultural value of respeto (i.e., obedience, deference, decorum, and public behavior), parents select parenting practices (e.g., corporal punishment, reasoning) that best teach children about these behavioral expectations. This model is supported by past findings that Mexican American parents who emphasize familism are more likely monitor their children as they reach adolescence (Romero & Ruiz, 2007). In regards to respeto, a mother who wishes to teach her child to obey without question may select to use a spank as a means of most effectively reinforcing this socialization message; in this case, the mother’s use of spanking and the socialization message that the child must obey without question are both regarded as predictors of the child’s behavioral functioning. The inclusion of these two aspects of parenting—socialization based on cultural values and parenting practices/styles used to reinforce these socialization messages—represents an important bridge between the parenting and ethnicracial socialization literatures by recognizing both the robust relation between parenting practices/styles and child behavior (Baumrind, 1991; McMahon & Wells, 1998; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992) and emerging evidence that children’s behavioral functioning is associated with socialization messages (Hughes et al., 2006; Knight et al., 1993).

Figure 1.

A Culturally informed model of Latino parenting and child functioning. Note: Dotted lines represent paired variables that are theoretically inconsistent.

Also reflected in the framework is the cultural incongruence between Latino and mainstream U.S. American parenting. Representing global orientations of collectivism (in which group needs supersede individual ones) versus individualism, respectively, respeto may lead to practices/styles that socialize children in obedience, deference and proper public behavior, whereas independence and its dimensions of separateness, self-sufficiency, and self-confidence, may lead to practices/styles emphasizing negotiation, assertiveness, and exploration (Harwood et al., 1999). Parents who socialize their children to obey without question are prioritizing obedience over negotiation (i.e., socialization message); this parent may choose to spank rather than reason with her child (i.e., parenting practice) when the child questions a command. Likewise, parents who encourage their children to defer to adult wishes are choosing to focus on deference rather than assertiveness; as a parenting practice, this parent may choose to ignore rather than invite her child’s opinion. Notably, although non-Latino children are undoubtedly expected to be obedient and deferential in some situations (indeed, such behaviors are the basis of many EBTs for children and parents), the present study supports the notion that an emphasis on unquestioning obedience and highly prescribed prosocial behaviors, over and above other child behaviors such as autonomy, may be distinctly characteristic of Latino cultures in comparison to mainstream U.S. American culture (Diaz-Guerrero, 1991; Harwood, 1992; Harwood et al., 1999). Given competing ideologies, then, parental acculturation and enculturation may be key determinants in how parents balance these opposing values and practices (Dumka, Roosa, & Jackson, 1997; Gonzalez-Ramos, Zayas, & Cohen, 1998; Harrison et al., 1990; Planos, Zayas, & Busch-Rossnagel, 1995, 1997). Indeed, mothers in the present study reported that in contrast to parents in their countries of origin, they were more likely to balance respeto with communication.

Empirical work is now needed to examine such a framework of Latino parenting and child functioning. Because practices related to respeto and independence become relevant for parents when children are 4 or 5 years old, a focus on the preschool developmental period may shed light on the potential conflict between respeto- and independence- driven parenting, when socialization of these values emerges. Longitudinal studies would allow for an examination of shifts in parenting over time, as children grow, and as parents encounter new situations.

Ultimately, socialization messages and the parenting practices/styles used to reinforce them that are predictive of child functioning in Latino preschoolers will inform our understanding of EBTs (e.g., parent training programs) and the ways in which they may require modifications to best serve Latino families. For example, evidence that a message underscoring the importance of sitting still and quietly outside the home (i.e., public behavior) is negatively related to children’s social skills could lead to modifications in which parents are encouraged to create situations in which children are allowed to explore their surroundings in ways that are culturally acceptable (e.g., in a park). In the same way, if the use of spanking to reinforce messages related to unquestioning obedience is associated with more child behavior problems, parent training programs could work with parents to identify the situations in which it is most important that their children show unquestioning obedience and explore alternate ways to teach this behavior. In other words, socialization messages that play a direct and indirect role in the adjustment of Latino children would need to be incorporated into existing parent training programs to optimize EBTs aimed at supporting Latino families in need of mental health services.

There are limitations to the present study that warrant mention. It is not known whether the present findings extend to other subgroups (e.g., Puerto Ricans, Ecuadorians) of Latinos or to Latino fathers. Because participants were mothers of preschoolers, it is not known how respeto-driven socialization messages or the corresponding parenting practices/styles may change as children get older. Finally, the behavioral manifestations of respeto may depend in part on the community context within which parents are raising their children so these findings may be specific to lowincome, urban families. Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that current models of parenting and child development may be enhanced by incorporating messages related to core cultural values such as respeto and thus have direct relevance to the mental health treatment of Latino families in the U.S.

Contributor Information

Esther J. Calzada, New York University School of Medicine, Child Study Center

Yenny Fernandez, New York University School of Medicine, Child Study Center.

Dharma E. Cortes, Harvard Medical School

References

- Alvy KT. Parent training today: A social necessity. Studio City, CA: Center for the Improvement of Child Caring; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arcia E, Johnson A. When respect means to obey: Immigrant Mexican mothers’ values for their children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1998;7:79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Baca Zinn M. Qualitative methods in family research: A look inside Chicano families. California Sociologist. 1982;5:58–79. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The contributions of the family to the development of competence in children. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1975;14:12–37. doi: 10.1093/schbul/1.14.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance abuse use. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:56–95. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Child maltreatment and optimal caregiving in social contexts. New York: Garland Publishing Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G. Intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. Family Process. 2006;45:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Cote LR. Cultural and parenting cognitions in acculturating cultures: 2. Patterns of prediction and structural coherence. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 2003;34:350–373. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Caughy M, Nettles S, O’Campo P, Lohrfink K. Neighborhood matters: Racial socialization of African-American children. Child Development. 2006;77:1220–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy M, O’Campo P, Randolph S, Nickerson K. The influence of racial socialization practices on the cognitive and behavioral competence of African-American preschoolers. Child Development. 2002;73:1611–1625. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Gaitan C. Socializing young children in Mexican-American families: An intergenerational perspective. In: Greenfield P, Cocking R, editors. Cross-cultural roots of minority child development. Hillside, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 55–86. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Guerrero R. Toward a psychological nationalism. Journal of Peace Psychology. 1997;3:373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Lopez V, Jacobs Carter S. Parenting interventions adapted for Latino families: Progress and prospects. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002. pp. 203–231. [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Roosa MW, Jackson KM. Risk, conflict, mother’s parenting, and children’s adjustment in low-income, Mexican immigrant and Mexican American families. Journal of marriage and the family. 1997;59:309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL, Landsverk JA. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1336–1343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Ramos G, Zayas LH, Cohen EV. Child-rearing values of low-income, urban Puerto Rican mothers of preschool children. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice. 1998;29:377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DB, Florsheim P. Patterns of family functioning and adolescent outcomes among urban African-American and Mexican-American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:436–457. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychoterapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43:531–548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison AO, Wilson MN, Pine CJ, Chan SQ, Buriel R. Family ecologies of ethnic minority children. Child Development. 1990;61:347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood R, Schoelmerich A, Schulze PA, Gonzalez Z. Cultural differences in maternal beliefs and behaviors: A study of middle-class Anglo and Puerto Rican mother-infant pairs in four everyday situations. Child Development. 1999;70:1005–1016. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood RL. The influence of culturally derived values on Anglo and Puerto Rican mothers’ perceptions of attachment behavior. Child Development. 1992;63:822–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood RL, Miller JG, Irizarry NL. Culture and attachment: Perceptions of the child in context. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African-American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:15–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parent’s ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal ME, Garza CA, Cota MK, Ocampo KA. Family socialization and the ethnic identity of Mexican-American children. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 1993;24:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. Childrearing as cultural adaptation. In: Leiderman PH, Tulkin SR, Rossemnfeld A, editors. Culture and Infancy: Variations in the human experience. New York: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Marin B. Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Wells KC. Conduct problems. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of childhood disorders. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau A, Kohn L, Hwang WC, LaFromboise T. State of the science of psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:113–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno RP. Teaching the alphabet: An exploratory look at maternal instruction in Mexican American families. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2002;24:191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK. Qualitative methods in social work research: Challenges and rewards. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Understanding ethnic diversity: The role of ethnic identity. American Behavioral Scientist. 1996;40:143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Planos R, Zayas LH, Busch-Rossnagel NA. Acculturation and teaching behaviors of Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science. 1995;17:225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Planos R, Zayas LH, Busch-Rossnagel NA. Mental health factors and teaching behaviors among low-income Hispanic mothers. Families in Society. 1997;78:4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Ruiz M. Does familism lead to increase parental monitoring?: Protective factors for coping with risky behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco C, Todorova ILG, Louie J. Making up for lost time: The experience of separation and reunification among immigrant families. Family Process. 2002;41:625–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration. Youth violence and substance abuse: 2001 update. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedijan A. Generational differences and similarities among Puerto Rican and Mexican mothers’experiences with familial ethnic socialization. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2006;23:445–464. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Rojas-Flores L. Learning from Latino parents: Combining etic and emic approaches to designing interventions. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002. pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zea MC, Asner-Self KK, Birman D, Buki LP. The Abbreviated Multidimentional Acculturation Scale: Empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:107–126. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]