Abstract

Background and Purpose

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a devastating disease characterized by increased pulmonary arterial pressure, which progressively leads to right-heart failure and death. A dys-regulated renin angiotensin system (RAS) has been implicated in the development and progression of PH. However, the role of the angiotensin AT2 receptor in PH has not been fully elucidated. We have taken advantage of a recently identified non-peptide AT2 receptor agonist, Compound 21 (C21), to investigate its effects on the well-established monocrotaline (MCT) rat model of PH.

Experimental Approach

A single s.c. injection of MCT (50 mg·kg−1) was used to induce PH in 8-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats. After 2 weeks of MCT administration, a subset of animals began receiving either 0.03 mg·kg−1 C21, 3 mg·kg−1 PD-123319 or 0.5 mg·kg−1 A779 for an additional 2 weeks, after which right ventricular haemodynamic parameters were measured and tissues were collected for gene expression and histological analyses.

Key Results

Initiation of C21 treatment significantly attenuated much of the pathophysiology associated with MCT-induced PH. Most notably, C21 reversed pulmonary fibrosis and prevented right ventricular fibrosis. These beneficial effects were associated with improvement in right heart function, decreased pulmonary vessel wall thickness, reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and favourable modulation of the lung RAS. Conversely, co-administration of the AT2 receptor antagonist, PD-123319, or the Mas antagonist, A779, abolished the protective actions of C21.

Conclusions and Implications

Taken together, our results suggest that the AT2 receptor agonist, C21, may hold promise for patients with PH.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| GPCRsa | |

| Angiotensin AT1 receptor | |

| Angiotensin AT2 receptor | |

| Mas (MAS1) receptor | |

| MrgD (MRGPRD) receptor | |

| Enzymesb | |

| ACE | |

| ACE2 |

| LIGANDS | |

|---|---|

| A779 | |

| Alamandine | |

| Ang II, angiotensin II | |

| Ang-(1–7), angiotensin-(1–7) | |

| IL-1β | |

| PD-123319 | |

| TGF-β | |

| TNF-α |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guideto PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,bAlexander et al., 2013a,b,).

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a fatal lung disease characterized by endothelial dysfunction, hyper-proliferation of the pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and occlusive vascular remodelling (Badesch et al., 2007; Schermuly et al., 2011). These pathological changes lead to elevated BP in the pulmonary circulation, which progressively increases workload on the right ventricle (RV) to cause right-heart failure and death (Bogaard et al., 2009). The currently approved therapies for PH include anticoagulants, diuretics and oxygen for symptomatic relief, as well as vasodilators such as calcium channel blockers, endothelin receptor antagonists, PDE inhibitors, soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators and prostanoids, all of which reduce pulmonary vascular resistance and thereby improve right ventricular function (Cheever, 2005; Badesch et al., 2007). However, even with treatment, the overall prognosis remains poor, with high mortality rates (Thenappan et al., 2010), emphasizing the need to discover potential new therapies that arrest disease progression by interfering with pathomechanisms at several levels.

Several lines of evidence indicate a detrimental role for the renin angiotensin system (RAS) in the pathogenesis of PH (Lipworth and Dagg, 1994; Orte et al., 2000; Abraham et al., 2003; Chung et al., 2009). Elevated levels of renin, ACE, angiotensin II (Ang II) and angiotensin AT1 receptors have been observed in experimental models as well as patients with PH (Morrell et al., 1995; de Man et al., 2012). This increase in systemic and pulmonary components of the RAS adversely affects cardiopulmonary function and contributes to the disease pathogenesis. However, drugs that block the classical RAS, such as ACE inhibitors and AT1 receptor blockers, have produced mixed effects in the clinics for PH therapy, possibly due to drug-induced side effects such as systemic hypotension, cough and angioedema. While blockade of the RAS remains controversial for treating PH, their use in other forms of cardiovascular diseases has been associated with up-regulation of what has become known as the vasoprotective axis of the RAS, consisting of ACE2, angiotensin-(1–7) [Ang-(1–7)], Mas receptors and angiotensin AT2 receptors (Danyel et al., 2013; Santos et al., 2013).

In several models of cardiovascular disease, the beneficial effects seen with ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas receptor activation are similar to those seen by AT2 receptor activation (Tallant and Clark, 2003; Castro et al., 2005; Ferreira et al., 2010; Qi et al., 2011; 2012,; Sumners et al., 2013; Wagenaar et al., 2013). In a recent obesity study, chronic AT2 receptor activation led to an increase in ACE2 activity and Mas expression levels, further demonstrating the link among the protective components of the RAS (Ali et al., 2013). We and others have previously demonstrated that activation of the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas receptor axis of the RAS exerts protection against animal models of lung diseases (Shenoy et al., 2010; 2011; 2013,,). However, the role and functional significance of AT2 receptors in the lungs and pulmonary diseases has not been fully elucidated.

The expression of AT2 receptors in adult life is low, representing a major limitation for its characterization (de Gasparo et al., 2000; Kaschina and Unger, 2003). AT2 receptor levels are endogenously up-regulated in areas of tissue damage, as has been observed in models of cardiac, pulmonary, neuronal and skin injuries (Viswanathan and Saavedra, 1992; Tsutsumi et al., 1998; Li et al., 2005; Wagenaar et al., 2013). This increase may participate as a compensatory mechanism to minimize tissue injury. For example, animals overexpressing AT2 receptors display improved heart function following myocardial injury (Qi et al., 2012). Conversely, mice deficient in AT2 receptors exhibit aggravated heart injury and show increased mortality after myocardial insult (Adachi et al., 2003). Additionally, AT2 receptor-deficient mice have been found to be susceptible to acute lung injury (Imai et al., 2005). These observations provide strong evidence for a potential beneficial effect of AT2 receptor signalling in the heart and lungs (Adachi et al., 2003; Imai et al., 2005). In fact, the AT2 receptor is known to oppose many of the detrimental actions of the AT1 receptor, resulting in vasodilation, cell differentiation, reduced proliferation, apoptosis, decreased inflammation and diminished fibrosis (Yamada et al., 1996; Ruiz-Ortega et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2003; Yayama et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2007; Rompe et al., 2010). These AT2 receptor-mediated effects are important considerations in the treatment of PH, suggesting that AT2 receptor activation may offer potential therapeutic benefits against this disease.

Until recently, the effects of AT2 receptor activation have been difficult to ascertain due to lack of effective agonists that can selectively activate AT2 receptors rather than AT1 receptors and exhibit favourable in vivo kinetics. However, such a molecule, Compound 21 (C21) – the first known non-peptide AT2 receptor agonist – was recently synthesized (Wan et al., 2004). It is well known that PH is associated with increased inflammation, oxidative stress, interstitial fibrosis and maladaptive ventricular remodelling (Hassoun et al., 2009). C21 has been shown to exert potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-fibrotic and anti-trophic activities in several distinct models of cardiovascular diseases, without affecting basal systemic BP (Steckelings et al., 2011). Given the fact that C21 displays such protective actions, we hypothesized that chronic administration of this compound would provide beneficial cardiopulmonary outcomes in the well-established monocrotaline (MCT) model of PH.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the NIH guidelines and were approved by the IACUC at the University of Florida. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). A total of 84 animals were used in the experiments described here.

To induce PH, male Sprague Dawley rats (250–300 g, Charles River, Raleigh, NC, USA) were injected with a single s.c. dose of 50 mg·kg−1 MCT (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 8 weeks of age. Control animals were treated with saline. Initially, a small pilot study was performed (Control, n = 3; MCT, n = 4), in which animals were killed 2 weeks after the MCT injection, and progression of PH was assessed as described below. Based upon this study, we determined that 2 weeks was an appropriate time point to initiate C21 treatment.

Therefore, in the main study, 2 weeks after MCT or saline injection, animals received the following treatments: 0.03 mg·kg−1·day−1 C21 (i.p.) (kindly provided by Vicore Pharma, Gothenburg, Sweden) (C21, n = 9; MCT + C21, n = 14); 3 mg·kg−1·day−1 PD-123319 (i.p.) (AT2 receptor antagonist; Sigma-Aldrich) (MCT + PD, n = 6); C21 and PD (MCT + C21 + PD, n = 6); 0.5 mg·kg−1·day−1 A779 (s.c.) (Mas antagonist; Bachem, Torrance, CA, USA) (MCT + A779, n = 7); C21 and A779 [MCT + C21 + A779, n = 7] or saline (Control, n = 14 and MCT, n = 14) for 2 weeks. The doses of each compound were selected based upon publsihed work and previous studies (Grobe et al., 2007; Kaschina et al., 2008). This dose of C21 was effective in previous studies, including the original article describing the design and synthesis of C21 (Wan et al., 2004; Kaschina et al., 2008; Steckelings et al., 2011). Four weeks after MCT injection, right ventricular haemodynamic parameters were measured and tissues were collected for gene expression and histological analyses.

Systemic BP

Systemic BPs were determined weekly via a non-invasive tail-cuff method (CODA; Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT, USA). Briefly, animals were restrained and placed on a heated surface to which the animals had been conditioned prior to the experiment. An occlusion cuff was placed high on the tail followed by a differential pressure transducer. As the occlusion cuff is triggered, the transducer measures the blood volume in the tail to obtain systemic BP recorded via the CODA software (Kent Scientific).

Haemodynamic measurements

The right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) was measured in anaesthetized animals (isoflurane induced at 5% and maintained at 2.5%) using a fluid-filled Silastic® catheter (Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA), which was inserted inside the right descending jugular vein and advanced to the RV. The catheter was connected to a pressure transducer that was interfaced to a PowerLab (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) signal transduction unit. The waveform was used to confirm the positioning of the catheter in the ventricle. RVSP, dP/dtmax, dP/dtmin and right ventricular end diastolic pressure (RVEDP) were obtained using the LabChart program supplied along with the PowerLab system. All other animals were measured after 4 weeks of initial MCT injection.

Hypertrophy and histological analysis

To calculate right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), the wet weight of RV and left ventricle plus ventricular septum (LV + S) was determined. RVH was expressed as the ratio of RV/[LV + S] weights. The RV was further processed for histological analysis of collagen content. Briefly, RV was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm and stained with Picro-Sirius Red. Interstitial fibrosis was determined at 100× magnification using the ImageJ program from National Institutes of Health as previously described (Shenoy et al., 2013). A minimum of 10 separate images from different (non-overlapping) regions of the RV were obtained and analysed by two individuals who were not aware of the treatments. The results for each animal were then averaged for subsequent statistical analysis. To carry out histological examination of the lung, the left lung was isolated and perfused with PBS followed by 10% neutral buffered formalin under constant pressure with the bronchus subsequently tied to ensure that the lung maintained an inflated state during fixation. To measure pulmonary medial wall thickness, 5-μm-thick lung sections were cut paraffin-embedded and stained for α-smooth muscle actin (1:600, clone51A4; Sigma-Aldrich). For each rat, around 20 vessels with an external diameter of 25–50 μm were considered and the average was calculated by two individuals who were not aware of the treatment. The percent medial wall thickness was calculated using the formula: % Medial wall thickness = [(medial thickness × 2)/external diameter] ×100 (n = 5 rats per group). Media thickness was defined as the distance between the lamina elastica interna and lamina elastica externa.

qPCR analysis

Real-time semi-quantitative PCR (qPCR) was used to determine mRNA levels of the renin angiotensin system components, ACE, ACE2, AT1 receptor, AT2 receptor and Mas receptor, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, TNF-α and TGF-β, as previously described (Shenoy et al., 2013). Briefly, total RNA was isolated from lung tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's specifications. The RNA concentration was calculated from the absorbance at 260 nm, and RNA quality was assured by 260/280 ratio. Only RNA samples exhibiting an absorbance ratio (260/280) of >1.8 were used for further experiments. The RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Ambion, Foster City, CA, USA) to remove any genomic DNA. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng RNA with iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). qPCR was performed in 96-well PCR plates using Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) in duplicate using the ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression was measured by the ΔΔCT method and was normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels. Data are presented as the fold change of the gene of interest relative to that of control animals.

Data analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v5 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). The unpaired t-test was performed to analyse data from the 2 week pilot study. One-way anova was used for data from the primary study, followed by the Newman–Keuls post hoc test. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

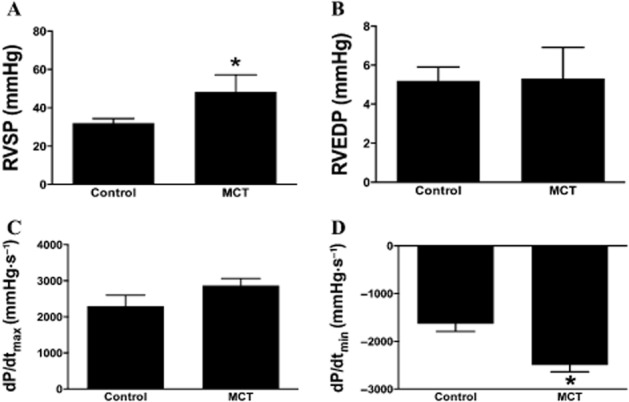

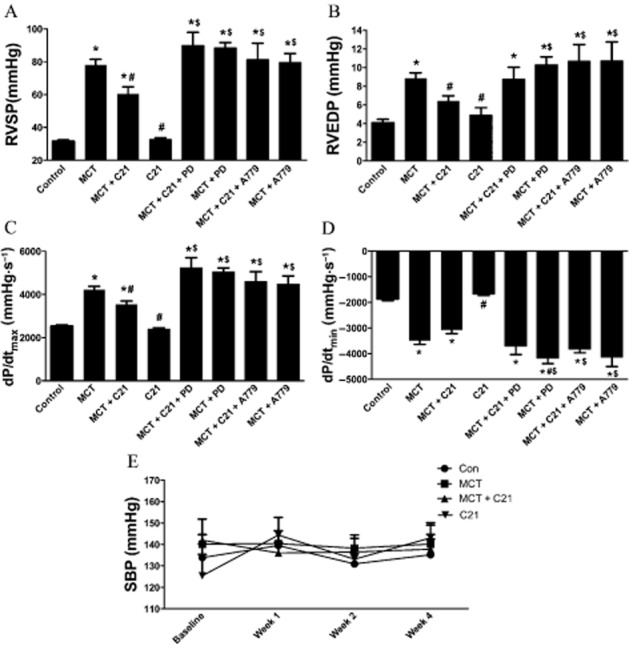

Effects of MCT and C21 on the right ventricular function

As an indication of increased pulmonary pressures, we measured RVSP. Two weeks after the MCT injection, rats manifested significantly increased RVSP indicative of the induction of PH (Figure 1A). As the primary cause of death in PH is cor pulmonale, we assessed RV function as well. Right heart dysfunction was also present at 2 weeks, as indicated by a decrease in dP/dtmin (Figure 1D). However, RVEDP and dP/dtmax were not changed by 2 weeks after the MCT injection (Figure 1B and C). Based upon this, we initiated therapeutic intervention with C21 at 2 weeks after MCT injection and continued treatment daily for an additional 2 weeks. By 4 weeks after MCT, animals exhibited a further increase in RVSP (Figure 2A). However, C21-treated MCT animals displayed a significant attenuation of increased RVSP (Figure 2A). In contrast, these improvements were completely blocked by both the AT2 receptor antagonist, PD-123319, and the Mas receptor antagonist, A779. C21 treatment alone had no detrimental effects on the basal RVSP. Despite dramatic increases in cardiopulmonary pressures, neither MCT administration nor C21 treatment had an effect on systemic BP (Figure 2E). RV function was significantly altered in MCT animals, as measured by RVEDP, dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin (Figure 2B–D). Cardiac function appeared to improve with C21 treatment as shown by significant reduction in RVEDP and dP/dtmax (Figure 2B and C). Blocking the AT2 receptors with PD-123319 prevented this improvement. Interestingly, rats injected with MCT and the AT2 receptor blocker, PD-123319, displayed a further decline in dP/dtmin, compared with animals given MCT alone, suggesting a cardioprotective role of endogenous AT2 receptors. However, the Mas antagonist, A779, also inhibited the protective effects of C21, suggesting a connection between the Mas and AT2 receptors. C21 by itself did not alter the basal cardiac haemodynamics.

Figure 1.

Indications of pulmonary hypertension (PH) observed 2 weeks after monocrotaline (MCT) injection. (A) Increase in right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP). (B) No change in right ventricular end diastolic pressure (RVEDP) or (C) dP/dtmax. (D) Decrease in dP/dtmin. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus Control.

Figure 2.

Indications of pulmonary hypertension (PH) observed 4 weeks after monocrotaline (MCT) injection and effect of C21 treatment on right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP), RV function and systolic blood pressure (SBP). (A) RVSP, (B) right ventricular end diastolic pressure (RVEDP), (C) dP/dtmax, (D) dP/dtmin and (E) (SBP). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus Control; #P < 0.05 versus MCT; $P< 0.05 versus MCT + C21.

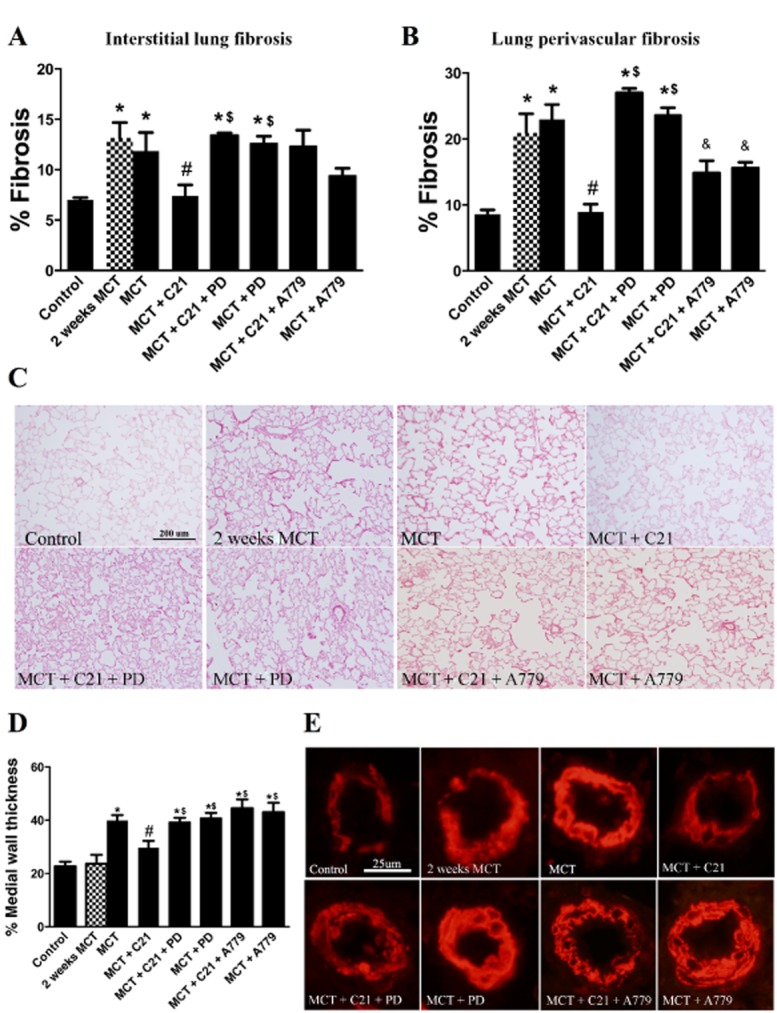

Effects of C21 treatment on MCT-induced lung pathology

Pulmonary vascular remodelling characterized by increased collagen deposition and increased vascular muscularization is associated with MCT-induced PH. With regard to lung fibrosis, collagen deposition was observed to be significantly higher in MCT-challenged animals as measured by Picro-Sirius Red staining. This increase was observed both in interstitial lung fibrosis as well as in perivascular fibrosis. These changes were obvious 2 weeks after MCT treatment and prior to any intervention with C21. Remarkably, C21 treatment of MCT rats reversed both interstitial and perivascular fibrosis, an effect that was blocked by PD-123319 (Figure 3A–C). Interestingly, treatment with A779 attenuated pulmonary fibrosis independent of C21 treatment. Thickening of the pulmonary artery walls is characteristic of MCT-induced PH. At 2 weeks, there is no significant muscularization of the pulmonary arteries but by 4 weeks after MCT, a twofold increase in the vessel wall thickening of the pulmonary vasculature was observed. This remodelling effect on the pulmonary vessels was significantly attenuated by C21 administration. This protective effect of C21 was lost by co-administration of PD-123319, as well as with A779 (Figure 3E and F). As the basal cardiac haemodynamics were unchanged in the group of rats receiving C21 alone, it was not included in the morphology studies.

Figure 3.

Effects of C21 on monocrotaline (MCT)-induced lung pathology. Quantification of (A) interstitial lung fibrosis and (B) lung perivascular fibrosis as measured by Picro-Sirius Red staining. (C) Representative images of lung fibrosis. (D) Relative quantification of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) stain of pulmonary vessels. (E) Representative images of α-SMA stained pulmonary vessels. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus Control; #& P < 0.05 versus MCT; $P < 0.05 versus MCT + C21; and & P < 0.05 versus all groups.

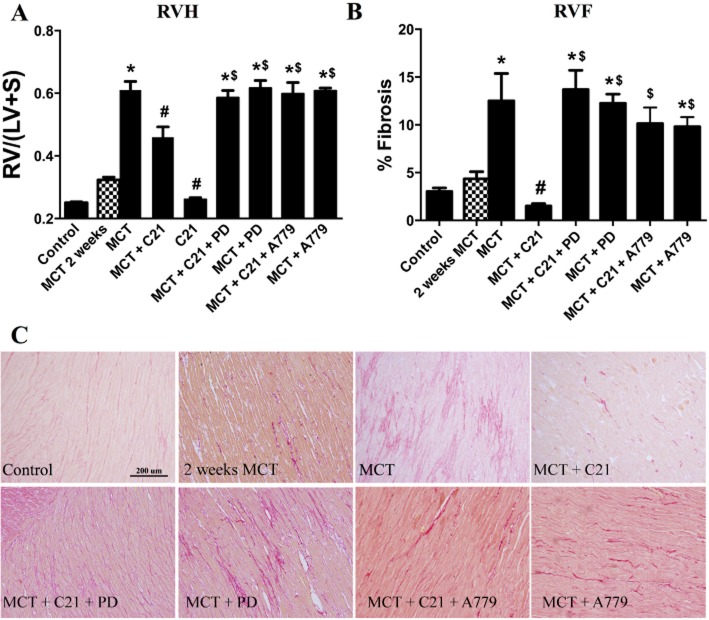

Effects of C21 on right ventricular remodelling

Hypertrophic and fibrotic remodelling of the RV occurs in response to increased pulmonary pressure, culminating in right heart dysfunction (Bradley et al., 1996). A t-test indicates that RV hypertrophy, as measured by increased RV to left ventricle plus septum (LV + S) weight ratio, was significantly increased 2 weeks after MCT injection. Four weeks after MCT injection, the RV/(LV + S) weight ratio was increased by approximately threefold (Figure 4A). Intervention with C21 significantly attenuated RVH, and this beneficial affect was prevented by both PD-123319 and A779. C21 treatment alone had no effect. In addition, MCT animals exhibited a threefold increase in RV fibrosis (RVF) (Figure 4B). It is pertinent to note that RVF was not evident after 2 weeks of MCT injection (Figure 4B). Two weeks of C21 treatment completely prevented RVF, with levels comparable to those of control animals. The beneficial effects of C21 treatment on RVF were abolished by the AT2 receptor antagonist, PD-123319 or by A779 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of monocrotaline (MCT) and C21 on right ventricular (RV) remodelling. (A) Adaptive right ventricular hypertrophy was determined by measuring the ratio of RV to left ventricle (LV) plus interventricular septum (S) weight ratio [RV/(LV + S)]. (B) Quantitative analysis of right ventricular fibrosis (RVF) as measured by Picro-Sirius Red staining. (C) Representative images of RVF. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus Control; #P < 0.05 versus MCT; $P < 0.05 versus MCT + C21.

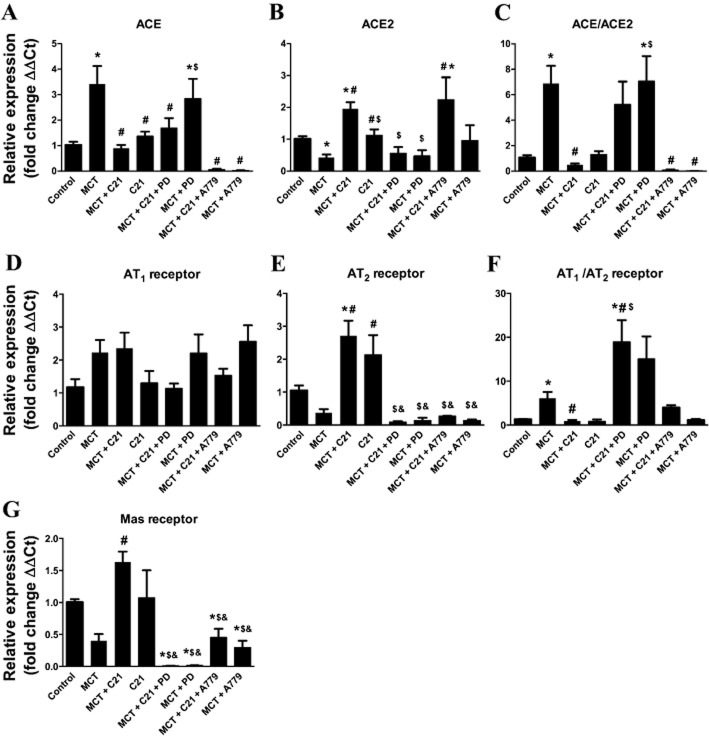

Favourable modulation of the lung RAS

Gene expression of various RAS components in the lungs was measured using qPCR. While MCT injection caused a threefold increase in ACE expression, C21 treatment restored this increase to control levels (Figure 5A). Furthermore, a decrease in ACE2 mRNA levels was observed in MCT-induced PH animals, which was reversed by C21 therapy. In fact, C21 treatment of MCT animals showed more than twofold increase in ACE2 levels (Figure 5B). When measured as a ratio to show the balance between the vasodeleterious and vasoprotective axes of the RAS, we observed that the ACE/ACE2 ratio was dramatically increased with MCT treatment. However, this ratio was restored to control levels by C21 treatment, and this beneficial effect was abolished by PD-123319. Indeed, PD-123319 appeared to further increase the ACE/ACE2 ratio, indicating worsening of the pathological condition (Figure 5C). Mas receptor blockade with A779 significantly reduced ACE mRNA levels (Figure 5A) but did not block the C21-induced increase in ACE2 levels (Figure 5B). Although there was a tendency for an increase in AT1 receptors and a decrease in AT2 receptors in the lung tissue of MCT-treated animals, no significant change in the expression of AT1 receptors was observed among the different experimental groups (Figure 5D). However, C21 treatment was associated with significantly increased lung AT2 receptors (Figure 5E). Both PD-123319 and A779 significantly inhibited this increase. When comparing the levels of AT1 receptors and AT2 receptors, we observed a significant increase in the AT1/AT2 receptor ratio of MCT lungs, and this ratio was completely normalized with C21 treatment (Figure 5F). PD-123319 exacerbated the MCT-induced increase in the AT1/AT2 receptor ratio, whereas A779 treatment did not alter this. Mas receptor expression levels were reduced by 50% in MCT-challenged animals and was significantly elevated in C21-treated MCT animals (Figure 5G). Administration of PD-123319 or A779 had a significant dampening effect on Mas receptor expression levels, further indicating a potential interrelationship between the AT2 receptor and the ACE2/Mas axis of the RAS (Figure 5E and G).

Figure 5.

Modulation of pulmonary renin angiotensin system (RAS) by monocrotaline (MCT) and C21 therapy. Relative changes in lung mRNA levels of the RAS genes, (A) ACE, (B) ACE2, (C) ACE/ACE2 ratio, (D) AT1 receptors, (E) AT2 receptors, (F) AT1 receptors/AT2 receptors ratio and (G) Mas receptors. Data are expressed as mean + SEM. *P < 0.05 versus Control; #&P < 0.05 versus MCT; and $P < 0.05 versus MCT + C21.

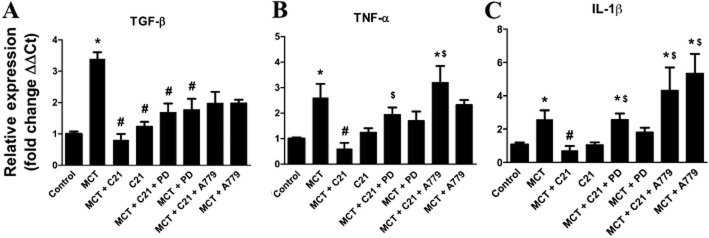

Reduction in lung inflammatory cytokines

Inflammation plays an integral role in the pathophysiology of PH (Hassoun et al., 2009). To measure the effects of C21 on inflammation, we measured gene expression of IL-1β, TNF-α and TGF-β in the lungs. Gene expression of IL-1β and TNF-α was increased in MCT animals by 2.5-fold, whereas that of TGF-β was increased by 3.5-fold (Figure 6). These increases were all normalized by C21 treatment in the MCT group, whereas C21 alone was without effect. Administration of PD-123319 abolished the C21-induced decreases in TNF-α and IL-1β expression (Figure 6B and C), but not TGF-β (Figure 6A). Blockade of the Mas receptor seemed to have a greater effect on these inflammatory cytokines than did PD-123319 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effects of monocrotaline (MCT) and C21 on the expression of pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory cytokines in the lungs. mRNA levels of (A) TGF-β, (B) TNF-α and (C) IL-1β. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus Control; #P < 0.05 versus MCT; $P < 0.05 versus MCT + C21.

Discussion

The present study examined the effects of C21, a non-peptide AT2 receptor agonist on PH and associated right ventricular remodelling in the well-established MCT model of lung injury. Chronic administration of C21 resulted in significant arrest of MCT-induced disease progression, along with improvement in the right heart function. The most striking observations were that C21 therapy reversed lung fibrosis and prevented myocardial fibrosis. Furthermore, lung inflammation and structural remodelling of the pulmonary arterioles were considerably reduced by C21 treatment. Importantly, the protective effects of C21 were abolished by the AT2 receptor antagonist, PD-123319, and by the Mas receptor antagonist, A779. Treatment with PD-123319 or A779 alone did not seem to worsen the pathophysiology associated with MCT-induced PH, although A779 alone did reduce lung perivascular fibrosis. Collectively, our results provide evidence that activation of AT2 receptors with non-peptide agonists such as C21 holds promise for PH therapy.

Recently, the involvement of RAS in the evolution and pathogenesis of lung diseases has received much attention. Ang II, the major effector peptide of the RAS, promotes vasoconstriction, proliferation, inflammation and fibrosis within the pulmonary vasculature and lung parenchyma via stimulation of AT1 receptors. These detrimental effects of Ang II may be counterbalanced by activation of AT2 receptors. In this regard, the discovery of C21 has been of great significance when evaluating the effects of direct chronic AT2 receptor stimulation. Previous studies have shown that AT2 receptor stimulation with C21 mediates a wide range of tissue-protective actions against animal models of myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes and spinal cord injury (Kaschina et al., 2008; Gelosa et al., 2009; Namsolleck et al., 2013). In our current study, we found a marked beneficial effect of C21 against MCT-induced PH pathophysiology. Of particular interest was that the treatment with C21 was selective in targeting the pulmonary haemodynamics, without affecting basal systemic BP. This is clinically relevant, as drug-induced lowering of systemic BP can prove counterproductive in patients with PH, who already have compromised heart function.

The marked reversal of pulmonary fibrosis along with the inhibition of right heart fibrosis is a remarkable and noteworthy effect of C21 treatment. We observed a 51% reduction of overall lung fibrosis and a 57% reduction in perivascular fibrosis in the lungs when compared with the MCT animals killed at the 2 week time point. This reversal appears to be a direct effect of C21 actions in the lung, the primary site of injury. It is well recognized that Ang II induces hypertrophic and fibrotic effects in several tissues via AT1 receptor-mediated activation of the MAPKs (Hunyady and Catt, 2006). Conversely, AT2 receptor activation inhibits Ang II-induced MAPK signalling to exert anti-hypertrophic and anti-fibrotic effects (Bedecs et al., 1997). The pathways associated with AT2 receptor activation include regulation of TGF-β, MMP-2, collagen I and TIMP-1 mRNA and protein expression, each being potent regulators of extracellular matrix deposition and remodelling (Nabeshima et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2007; Jing et al., 2009). Specifically, we observed mitigation of MCT-induced increase in TGF-β mRNA levels in the lungs. Notably, the substantial anti-fibrotic effects of C21 may provide a novel approach in the treatment of PH.

The beneficial effects of AT2 receptor signalling may be mediated, in part, through the ACE2-Ang-(1–7)-Mas axis. In this context, we observed increased pulmonary levels of ACE2 with C21 treatment with a concomitant decrease in ACE expression. Furthermore, C21 treatment normalized the AT1/AT2 receptor ratio to restore the lung RAS balance. A779 effectively blocked many of the beneficial effects observed with C21 treatment; however, it could not effectively block the increase in ACE2 expression. This might indicate a direct connection between AT2 receptor activation and transcription of ACE2 that is independent of the Mas receptor. C21 and Ang-(1–7) lack affinity for the AT1 receptor; however, Ang-(1–7) does have a low affinity for the AT2 receptor, while A779 does not (Bosnyak et al., 2011). From this, we can infer that A779 can only block C21 and Ang-(1–7) actions at the Mas receptor and could leave Ang-(1–7) to bind to AT2 receptors, possibly contributing to the lower fibrotic effect seen in the lung vasculature observed with A779 treatment. The decrease in ACE expression caused by A779 treatment was unexpected and an observation that we cannot fully explain at this time. However, the decrease in ACE potentially explains the reduced level of pulmonary vascular fibrosis observed in animals treated with A779. The decrease in ACE mRNA could result in a decrease in Ang II production and binding to the AT1 receptor, which is known to be a pro-fibrotic pathway (Weber and Brilla, 1991).

The parallels between previous studies and our current investigation further validate an underlying connection between AT2 receptors and the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas axis. For example, Zisman et al. (2003) demonstrated that enzymic activity of ACE2 and the subsequent formation of Ang-(1–7) correlated positively with AT2 receptor density in failing human hearts of patients with PH. Castro et al. (2005) also suggested a functional interaction of the Ang-(1–7/Mas axis with the AT2 receptor. Similarly, chronic AT2 receptor activation was associated with increases in ACE2 activity and Mas expression (Ali et al., 2013). Furthermore, inactivation of AT2 receptors was found to exacerbate acute lung injury in ACE2 knockout mice (Imai et al., 2005), whereas activation of both Mas receptors and AT2 receptors resulted in cardiopulmonary protective effects in a neonatal hyperoxia model of lung injury (Wagenaar et al., 2013). Collectively, evidence suggests a direct interaction between AT2 receptors and the Mas receptors. It is possible that the actions of C21 may not be selective for the AT2 receptors but may interact directly or indirectly with the Mas receptors. Preliminary studies from our collaborators have uncovered the possibility of dimerization of the AT2 receptors and the Mas receptors (Villela et al., 2015). If indeed these receptors dimerize, it could explain the similar beneficial effects seen when either receptor is activated. In this study, the ability of A779 to block the actions of C21 and decrease AT2 receptor expression levels might also suggest a possible heterodimerization of the receptors for pathways that contribute to vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, but not for pathways contributing to perivascular fibrosis. Further studies are needed to confirm this possibility and elucidate the possible mechanism(s) for this interaction, as it may vary depending upon the particular outcome and/or tissue investigated. Furthermore, the recent finding of alamandine has added another component to the protective RAS. Alamandine acts in a manner similar to Ang-(1–7) when binding to the Mas-related GPCR, MrgD, and is effectively antagonized by PD-123319 but not A779 (Lautner et al., 2013; Villela et al., 2015). These novel findings suggest an extensive and complex set of interactions and compensatory mechanisms among the protective components of the RAS with comparably extensive potential for therapeutic developments.

There is increasing appreciation for the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of PH. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with endothelial dysfunction and abnormal remodelling of the pulmonary vasculature, which contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of PH (Humbert et al., 1995; Hassoun et al., 2009; Budd and Holmes, 2012). The beneficial effects of C21 treatment on MCT-induced lung injury may be mediated by reduced inflammation, as demonstrated by the decreased levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and TGF-β. Previous studies have shown direct anti-inflammatory effects of C21 via inhibition of NF-κB, a potent mediator of inflammation (Rompe et al., 2010). The inhibition of cytokine elevation by C21 was nullified by treatment with either PD-123319, or A779 treatment. Collectively, a combination of decreases in lung pro-inflammatory cytokines and favourable modulation of the local lung RAS may account for the beneficial effects of C21.

PH is commonly associated with increased afterload, which causes maladaptive remodelling of the RV, characterized by hypertrophy and fibrosis (Bogaard et al., 2009). In addition, persistent pressure overload induces cardiomyocyte death and contractile dysfunction, which eventually leads to end-organ failure. In fact, RV function is the major determinant of survival in patients with PH. The beneficial outcomes of C21 treatment were associated with decreased ventricular remodelling and improved cardiac function. Particularly, the effects of C21 were more pronounced on right ventricular contractility and relaxation as measured by dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin respectively. It is conceivable that the observed anti-fibrotic and anti-hypertrophic effects of C21 treatment could be responsible for the improved cardiac function. Previous reports have demonstrated direct cardiac effects of C21 in animal models of cardiovascular diseases (Kaschina et al., 2008). Alternatively, the remarkable beneficial effects of 21 on the lung morphology may, in turn, minimize the RV dysfunction typically observed in PH.

There exists an urgent medical need to discover novel targets/drugs to treat PH, a disease with limited therapeutic options. Our study provides evidence that AT2 receptor activation with C21 is an effective strategy for PH therapy. C21 treatment not only induces remarkable reduction in RVSP but also exerts potent anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects that are associated with improved cardiac function. Importantly, the anti-fibrotic effect of C21 would be a novel approach to the treatment of PH. These experimental findings suggest that AT2 receptor agonists such as C21 should be further investigated in the clinic as potential therapeutic agents for treating PH.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Vicore Pharma for the gift of Compound 21, as well as Ms. Marda Jorgensen for her technical assistance and help with immunohistochemistry. This work was supported by NIH RO1grants HL102033 and HL056921 awarded to M. K. R. and M. J. K.; AHA Pre-Doctoral Fellowship 11PRE7390025 awarded to E. B.; and AHA grant SDG12080302 awarded to V. S.

Glossary

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- Ang-(1-7)

angiotensin-(1–7)

- C21

compound 21

- MCT

monocrotaline

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- RAS

renin angiotensin system

- RV

right ventricle

- RVEDP

right ventricular end diastolic pressure

- RVF

right ventricular fibrosis

- RVH

right ventricular hypertrophy

- RVSP

right ventricular systolic pressure

Disclosures

None.

Author contributions

E. B. designed and performed animal experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript; V. S. performed haemodynamic measurements and provided intellectual contributions; A. R. and A. E. performed animal experiments; A. H. and A.O. contributed to tissue staining; J. F. performed qPCR; M. K. R. and T. U. provided intellectual contributions; U. M. S. and C. S. provided intellectual support and helped prepare the manuscript; and M. J. K. supervised all experiments, analysed data and helped prepare the manuscript. All co-authors read and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Abraham WT, Raynolds MV, Badesch DB, Wynne KM, Groves BM, Roden RL, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme DD genotype in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: increased frequency and association with preserved haemodynamics. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2003;4:27–30. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2003.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi Y, Saito Y, Kishimoto I, Harada M, Kuwahara K, Takahashi N, et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor deficiency exacerbates heart failure and reduces survival after acute myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2003;107:2406–2408. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072763.98069.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013a;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2013b;170:1797–1867. doi: 10.1111/bph.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Q, Wu Y, Hussain T. Chronic AT2 receptor activation increases renal ACE2 activity, attenuates AT1 receptor function and blood pressure in obese Zucker rats. Kidney Int. 2013;84:931–939. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badesch DB, Abman SH, Simonneau G, Rubin LJ, McLaughlin VV. Medical therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: updated ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131:1917–1928. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedecs K, Elbaz N, Sutren M, Masson M, Susini C, Strosberg AD, et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptors mediate inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and functional activation of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase. Biochem J. 1997;325(Pt 2):449–454. doi: 10.1042/bj3250449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaard HJ, Abe K, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Voelkel NF. The right ventricle under pressure: cellular and molecular mechanisms of right-heart failure in pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2009;135:794–804. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosnyak S, Jones ES, Christopoulos A, Aguilar MI, Thomas WG, Widdop RE. Relative affinity of angiotensin peptides and novel ligands at AT1 and AT2 receptors. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;121:297–303. doi: 10.1042/CS20110036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SP, Auger WR, Moser KM, Fedullo PF, Channick RN, Bloor CM. Right ventricular pathology in chronic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:584–587. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd DC, Holmes AM. Targeting TGFβ superfamily ligand accessory proteins as novel therapeutics for chronic lung disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro CH, Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Bader M, Alenina N, Almeida AP. Evidence for a functional interaction of the angiotensin-(1-7) receptor Mas with AT1 and AT2 receptors in the mouse heart. Hypertension. 2005;46:937–942. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000175813.04375.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheever KH. An overview of pulmonary arterial hypertension: risks, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20:16. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200503000-00005. , quiz 117–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WK, Deng L, Carroll JS, Mallory N, Diamond B, Rosenzweig EB, et al. Polymorphism in the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AGTR1) is associated with age at diagnosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danyel LA, Schmerler P, Paulis L, Unger T, Steckelings UM. Impact of AT2-receptor stimulation on vascular biology, kidney function, and blood pressure. Integr Blood Press Control. 2013;6:153–161. doi: 10.2147/IBPC.S34425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira AJ, Shenoy V, Qi Y, Fraga-Silva RA, Santos RA, Katovich MJ, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activation protects against hypertension-induced cardiac fibrosis involving extracellular signal-regulated kinases. Exp Physiol. 2010;96:287–294. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.055277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International Union of Pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelosa P, Pignieri A, Fandriks L, de Gasparo M, Hallberg A, Banfi C, et al. Stimulation of AT2 receptor exerts beneficial effects in stroke-prone rats: focus on renal damage. J Hypertens. 2009;27:2444–2451. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283311ba1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobe JL, Mecca AP, Lingis M, Shenoy V, Bolton TA, Machado JM, et al. Prevention of angiotensin II-induced cardiac remodeling by angiotensin-(1-7) Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H736–H742. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00937.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun PM, Mouthon L, Barbera JA, Eddahibi S, Flores SC, Grimminger F, et al. Inflammation, growth factors, and pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S10–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert M, Monti G, Brenot F, Sitbon O, Portier A, Grangeot-Keros L, et al. Increased interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 serum concentrations in severe primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1628–1631. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.5.7735624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunyady L, Catt KJ. Pleiotropic AT1 receptor signaling pathways mediating physiological and pathogenic actions of angiotensin II. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:953–970. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XY, Gao GD, Du XJ, Zhou J, Wang XF, Lin YX. The signalling of AT2 and the influence on the collagen metabolism of AT2 receptor in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts. Acta Cardiol. 2007;62:429–438. doi: 10.2143/AC.62.5.2023404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing T, Wang H, Srivenugopal KS, He G, Liu J, Miao L, et al. Conditional expression of type 2 angiotensin II receptor in rat vascular smooth muscle cells reveals the interplay of the angiotensin system in matrix metalloproteinase 2 expression and vascular remodeling. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24:103–110. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschina E, Unger T. Angiotensin AT1/AT2 receptors: regulation, signalling and function. Blood Press. 2003;12:70–88. doi: 10.1080/08037050310001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschina E, Grzesiak A, Li J, Foryst-Ludwig A, Timm M, Rompe F, et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation: a novel option of therapeutic interference with the renin-angiotensin system in myocardial infarction? Circulation. 2008;118:2523–2532. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.784868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautner RQ, Villela DC, Fraga-Silva RA, Silva N, Verano-Braga T, Costa-Fraga F, et al. Discovery and characterization of alamandine: a novel component of the renin-angiotensin system. Circ Res. 2013;112:1104–1111. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Culman J, Hortnagl H, Zhao Y, Gerova N, Timm M, et al. Angiotensin AT2 receptor protects against cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal injury. FASEB J. 2005;19:617–619. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2960fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipworth BJ, Dagg KD. Vasoconstrictor effects of angiotensin II on the pulmonary vascular bed. Chest. 1994;105:1360–1364. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.5.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Man FS, Tu L, Handoko ML, Rain S, Ruiter G, Francois C, et al. Dysregulated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system contributes to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:780–789. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0411OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell NW, Atochina EN, Morris KG, Danilov SM, Stenmark KR. Angiotensin converting enzyme expression is increased in small pulmonary arteries of rats with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1823–1833. doi: 10.1172/JCI118228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima Y, Tazuma S, Kanno K, Hyogo H, Iwai M, Horiuchi M, et al. Anti-fibrogenic function of angiotensin II type 2 receptor in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:658–664. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namsolleck P, Boato F, Schwengel K, Paulis L, Matho KS, Geurts N, et al. AT2-receptor stimulation enhances axonal plasticity after spinal cord injury by upregulating BDNF expression. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;51:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orte C, Polak JM, Haworth SG, Yacoub MH, Morrell NW. Expression of pulmonary vascular angiotensin-converting enzyme in primary and secondary plexiform pulmonary hypertension. J Pathol. 2000;192:379–384. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH715>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledge base of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Shenoy V, Wong F, Li H, Afzal A, Mocco J, et al. Lentivirus-mediated overexpression of angiotensin-(1-7) attenuated ischaemia-induced cardiac pathophysiology. Exp Physiol. 2011;96:863–874. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.056994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Li H, Shenoy V, Li Q, Wong F, Zhang L, et al. Moderate cardiac-selective overexpression of angiotensin II type 2 receptor protects cardiac functions from ischaemic injury. Exp Physiol. 2012;97:89–101. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.060673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rompe F, Artuc M, Hallberg A, Alterman M, Stroder K, Thone-Reineke C, et al. Direct angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation acts anti-inflammatory through epoxyeicosatrienoic acid and inhibition of nuclear factor kappaB. Hypertension. 2010;55:924–931. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.147843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Suzuki Y, Egido J. Angiotensin II activates nuclear transcription factor-kappaB in aorta of normal rats and in vascular smooth muscle cells of AT1 knockout mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(Suppl. 1):27–33. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.suppl_1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Verano-Braga T, Bader M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, angiotensin-(1-7) and Mas: new players of the renin-angiotensin system. J Endocrinol. 2013;216:R1–R17. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Wilkins MR, Grimminger F. Mechanisms of disease: pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:443–455. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy V, Ferreira AJ, Qi Y, Fraga-Silva RA, Diez-Freire C, Dooies A, et al. The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiogenesis-(1-7)/Mas axis confers cardiopulmonary protection against lung fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1065–1072. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1840OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy V, Qi Y, Katovich MJ, Raizada MK. ACE2, a promising therapeutic target for pulmonary hypertension. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy V, Gjymishka A, Jarajapu YP, Qi Y, Afzal A, Rigatto K, et al. Diminazene attenuates pulmonary hypertension and improves angiogenic progenitor cell functions in experimental models. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:648–657. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0880OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckelings UM, Larhed M, Hallberg A, Widdop RE, Jones ES, Wallinder C, et al. Non-peptide AT2-receptor agonists. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumners C, Horiuchi M, Widdop RE, McCarthy C, Unger T, Steckelings UM. Protective arms of the renin-angiotensin-system in neurological disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40:580–588. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallant EA, Clark MA. Molecular mechanisms of inhibition of vascular growth by angiotensin-(1-7) Hypertension. 2003;42:574–579. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000090322.55782.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thenappan T, Shah SJ, Rich S, Tian L, Archer SL, Gomberg-Maitland M. Survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a reappraisal of the NIH risk stratification equation. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1079–1087. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00072709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi Y, Matsubara H, Ohkubo N, Mori Y, Nozawa Y, Murasawa S, et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor is upregulated in human heart with interstitial fibrosis, and cardiac fibroblasts are the major cell type for its expression. Circ Res. 1998;83:1035–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.10.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villela D, Leonhardt J, Patel N, Joseph J, Kirsch S, Hallberg A, et al. Angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R) and receptor Mas: a complex liaison. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015;128:227–234. doi: 10.1042/CS20130515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Saavedra JM. Expression of angiotensin II AT2 receptors in the rat skin during experimental wound healing. Peptides. 1992;13:783–786. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(92)90187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar GT, el Laghmani H, Fidder M, Sengers RM, de Visser YP, de Vries L, et al. Agonists of MAS oncogene and angiotensin II type 2 receptors attenuate cardiopulmonary disease in rats with neonatal hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L341–L351. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00360.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y, Wallinder C, Plouffe B, Beaudry H, Mahalingam AK, Wu X, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of the first selective nonpeptide AT2 receptor agonist. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5995–6008. doi: 10.1021/jm049715t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber KT, Brilla CG. Pathological hypertrophy and cardiac interstitium. Fibrosis and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. Circulation. 1991;83:1849–1865. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.6.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Horiuchi M, Dzau VJ. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor mediates programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:156–160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayama K, Hiyoshi H, Imazu D, Okamoto H. Angiotensin II stimulates endothelial NO synthase phosphorylation in thoracic aorta of mice with abdominal aortic banding via type 2 receptor. Hypertension. 2006;48:958–964. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000244108.30909.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Biermann T, Luther C, Unger T, Culman J, Gohlke P. Contribution of bradykinin and nitric oxide to AT2 receptor-mediated differentiation in PC12 W cells. J Neurochem. 2003;85:759–767. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisman LS, Keller RS, Weaver B, Lin Q, Speth R, Bristow MR, et al. Increased angiotensin-(1-7)-forming activity in failing human heart ventricles: evidence for upregulation of the angiotensin-converting enzyme homologue ACE2. Circulation. 2003;108:1707–1712. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000094734.67990.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]