Significance

Late-stage estrogen receptor α (ERα)-positive breast and ovarian cancers exhibit many regulatory alterations and therefore resist therapy. Our novel ERα inhibitor, BHPI, stops growth and often kills drug-resistant ERα+ cancer cells and induces rapid and substantial tumor regression in a mouse model of human breast cancer. BHPI distorts a normally protective estrogen–ERα-mediated activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) and elicits sustained UPR activation. The UPR cannot be deactivated because BHPI, acting at a second site, inhibits production of proteins that normally help turn it off. This persistent activation converts the UPR from protective to lethal. Targeting therapy-resistant ERα-positive cancer cells by converting the UPR from cytoprotective to cytotoxic may hold significant therapeutic promise.

Keywords: estrogen receptor, drug discovery, breast cancer, unfolded protein response, ovarian cancer

Abstract

Recurrent estrogen receptor α (ERα)-positive breast and ovarian cancers are often therapy resistant. Using screening and functional validation, we identified BHPI, a potent noncompetitive small molecule ERα biomodulator that selectively blocks proliferation of drug-resistant ERα-positive breast and ovarian cancer cells. In a mouse xenograft model of breast cancer, BHPI induced rapid and substantial tumor regression. Whereas BHPI potently inhibits nuclear estrogen–ERα-regulated gene expression, BHPI is effective because it elicits sustained ERα-dependent activation of the endoplasmic reticulum (EnR) stress sensor, the unfolded protein response (UPR), and persistent inhibition of protein synthesis. BHPI distorts a newly described action of estrogen–ERα: mild and transient UPR activation. In contrast, BHPI elicits massive and sustained UPR activation, converting the UPR from protective to toxic. In ERα+ cancer cells, BHPI rapidly hyperactivates plasma membrane PLCγ, generating inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3), which opens EnR IP3R calcium channels, rapidly depleting EnR Ca2+ stores. This leads to activation of all three arms of the UPR. Activation of the PERK arm stimulates phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), resulting in rapid inhibition of protein synthesis. The cell attempts to restore EnR Ca2+ levels, but the open EnR IP3R calcium channel leads to an ATP-depleting futile cycle, resulting in activation of the energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase and phosphorylation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2). eEF2 phosphorylation inhibits protein synthesis at a second site. BHPI’s novel mode of action, high potency, and effectiveness in therapy-resistant tumor cells make it an exceptional candidate for further mechanistic and therapeutic exploration.

Estrogens, acting via estrogen receptor α (ERα), stimulate tumor growth (1–3). Approximately 70% of breast cancers are ERα-positive and most deaths due to breast cancer are in patients with ERα+ tumors (2, 4). Endocrine therapy using aromatase inhibitors to block estrogen production, or tamoxifen and other competitor antiestrogens, often results in selection and outgrowth of resistant tumors. Although 30–70% of epithelial ovarian tumors are ERα-positive (1), endocrine therapy is largely ineffective (5–7). After several cycles of chemotherapy, tumors recur as resistant ovarian cancer (5), and most patients die within 5 years (8).

Noncompetitive ERα inhibitors targeting this unmet therapeutic need, including DIBA, TPBM, TPSF, and LRH-1 inhibitors that reduce ERα levels, show limited specificity, require high concentrations (>5 μM), and usually have not advanced through preclinical development (9–12). These noncompetitive ERα inhibitors and competitor antiestrogens are primarily cytostatic and act by preventing estrogen–ERα action; therefore, they are largely ineffective in therapy-resistant ERα containing cancer cells that no longer require estrogens and ERα for growth.

To target the estrogen–ERα axis in therapy-resistant cancer cells, we developed (13) and implemented an unbiased pathway-directed screen of ∼150,000 small molecules. We identified ∼2,000 small molecule biomodulators of 17β-estradiol (E2)–ERα-induced gene expression, evaluated these biomodulators for inhibition of E2–ERα-induced cell proliferation, and performed simple follow-on assays to identify inhibitors with a novel mode of action. Here, we describe 3,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-methyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-indol-2-one (BHPI), our most promising small molecule ERα biomodulator.

In response to stress, cancer cells often activate the endoplasmic reticulum (EnR) stress sensor, the unfolded protein response (UPR). We recently showed that as an essential component of the E2–ERα proliferation program, estrogen induces a different mode of UPR activation, a weak anticipatory activation of the UPR before increased protein folding loads that accompany cell proliferation. This weak and transient E2–ERα-mediated UPR activation is protective (14). BHPI distorts this normal action of E2–ERα and induces a massive and sustained ERα-dependent activation of the UPR, converting UPR activation from cytoprotective to cytotoxic. Moreover, independent of its effect on the UPR and protein synthesis, BHPI rapidly suppresses E2–ERα-regulated gene expression.

Results

BHPI Is Effective in Drug-Resistant ERα+ Breast and Ovarian Cancer Cells.

We investigated BHPI’s effect on proliferation in therapy-sensitive and therapy-resistant cancer cells. BHPI (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B) completely inhibited proliferation of ERα+ breast (Fig. 1 A and E–G), endometrial (Fig. 1C), and ovarian (Fig. 1 B, H, and I) cancer cells, and had no effect in counterpart ERα− cell lines (Fig. 1D). At 100–1,000 nM, BHPI completely blocked proliferation in diverse drug-resistant cell lines: 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT)–resistant ZR-75-1 breast cancer cells (Fig. 1E); tamoxifen and fulvestrant/ICI 182,780 (ICI)-resistant BT-474 cells (Fig. 1F) (15); epidermal growth factor (EGF)-stimulated T47D breast cancer cells, which are resistant to 4-OHT, ICI, and raloxifene (RAL) (Fig. 1G); Caov-3 ovarian cancer cells, which are resistant to 4-OHT, ICI, and cisplatin (Fig. 1H) (16); and multidrug resistant OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cells, which are resistant to 5 μM ICI (Fig. 1I) and to paclitaxel, cisplatin, and other anticancer drugs (17, 18). BHPI blocked proliferation in all 15 ERα+ cell lines and at 10 μM had no effect on proliferation in all 12 ERα− cell lines tested (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Furthermore, BHPI blocked anchorage-independent growth of MCF-7 cells in soft agar (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Fig. 1.

BHPI selectively inhibits proliferation of ERα+ cancer cells sensitive or resistant to drug therapy. BHPI inhibits proliferation of ERα+ (A) MCF-7 breast, (B) PEO4 ovarian, and (C) ECC-1 endometrial cancer cells with no effects on (D) counterpart ERα− cancer cells. Effects of BHPI on proliferation of drug-resistant cells: tamoxifen- and ICI-resistant (E) ZR-75-1 cells and (F) BT-474 breast cancer cells. (G) T47D cells treated with 1 μM BHPI or competitor antiestrogens (4-OHT, RAL, ICI) in the presence or absence of E2 and/or EGF. Proliferation of (H) cisplatin-resistant Caov-3 ovarian cancer cells and (I) multidrug-resistant OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cells treated with BHPI, or the antiestrogens 4-OHT or ICI. Concentrations are as follows: E2, 1 nM (E, G, and H) or 10 nM (A–C, F, and I); EGF, 50 ng/mL (G); ICI, 1 μM (E, G, and H), 5 μM (I); 4-OHT, 1 μM (E, G, and H); RAL, 1 μM (G) “•” denotes cell number at day 0. Hatched bars denote antiestrogens (4-OHT, RAL, or ICI). Cell proliferation is expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

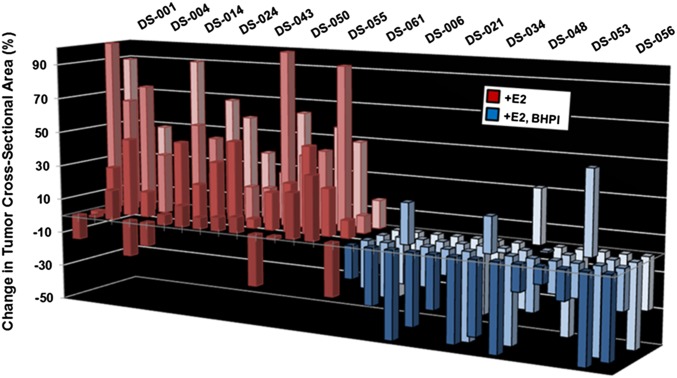

BHPI Induces Tumor Regression.

We next evaluated BHPI in a mouse xenograft model using MCF-7 cell tumors (19). For each tumor, cross-sectional area at day 0 (∼45 mm2) was set to 0%. Control (vehicle injected) and BHPI-treated mice were continuously exposed to estrogen. After daily i.p. injections for 10 d, the tumors in the vehicle-treated mice exhibited continued robust growth (Fig. 2, red bars). Whereas BHPI at 1 mg/kg every other day was ineffective (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), initiation of 15 mg/kg daily BHPI treatment resulted in rapid regression of 48/52 tumors (Fig. 2, blue bars). BHPI easily exceeded the goal of >60% tumor growth inhibition proposed as a benchmark more likely to lead to clinical response (20). Furthermore, BHPI, at 10 mg/kg every other day, ultimately stopped tumor growth and final tumor weight was reduced ∼60% compared with controls (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). BHPI was well tolerated; BHPI-treated and control mice exhibited similar food intake and weight gain (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C and D).

Fig. 2.

BHPI induces tumor regression in a mouse xenograft. Change in tumor cross-sectional area in mouse MCF-7 xenografts after 10 d of daily i.p. injections of either 15 mg/kg BHPI (blue) or vehicle control (red). Tumors had an average starting cross-sectional area of ∼45 mm2. For each tumor, area at day 0 was set to 0% change.

BHPI Is an ERα-Dependent Inhibitor of Protein Synthesis.

Surprisingly, BHPI greatly reduced protein synthesis in ERα+ cancer cells (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). If BHPI inhibits protein synthesis through ERα, it should only work in ERα+ cells, and ERα overexpression should increase its effectiveness. BHPI inhibited protein synthesis in all 14 ERα+ cell lines, with no effect on protein synthesis in all 12 ERα− cell lines (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). BHPI does not inhibit protein synthesis in ERα-negative MCF-10A breast cells, but gains the ability to inhibit protein synthesis when ERα is stably expressed in isogenic MCF10AER IN9 cells (Fig. 3B) (21). Notably, BHPI loses the ability to inhibit protein synthesis when ERα in the stably transfected cells is knocked down with siRNA (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A) or is degraded by ICI (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, increasing the ERα level in MCF7ERαHA cells (22), stably transfected to express doxycycline-inducible ERα, progressively increased BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis (Fig. 3E). BHPI does not work by activating the estrogen binding protein GPR30. BHPI has no effect on cell proliferation (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) or protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) in HepG2 cells that contain functional GPR30 (23), and activating GPR30 with G1 did not inhibit protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 B and C). Thus, ERα is necessary and sufficient for BHPI to inhibit protein synthesis.

Fig. 3.

BHPI selectively inhibits protein synthesis in ERα-positive cancer cells by activating PLCγ, depleting endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, and activating the UPR. (A) Protein synthesis in BHPI-treated ERα+ and ERα− cells (n = 4). CHX, cycloheximide. (B) ERα is sufficient to make a cell sensitive to BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis. Protein synthesis in parental ERα− MCF10A cells and ERα-expressing MCF10AER IN9 cells (n = 4). (C) RNAi knockdown of ERα abolishes BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis. Protein synthesis in MCF10AER IN9 cells treated with noncoding (NC) siRNA or ERα siRNA SmartPool followed by 100 nM BHPI (n = 4). (D) Protein synthesis and immunoblot analysis of ERα protein levels in MCF10AER IN9 cells pretreated with 1 μM ICI for 24 h to degrade ERα, followed by treatment with 100 nM BHPI (n = 4). (E) Residual protein synthesis (untreated cells are set to 100%) after treatment with 1 μM BHPI in doxycycline-treated MCF7ERαHA cells expressing increasing levels of ERα (n = 6). Western blot shows ERα levels in each sample. (F) Time course of phosphorylation of PERK and eIF2α following BHPI treatment of MCF-7 cells. (G) eIF2α phosphorylation and protein synthesis after 4-d treatment of MCF-7 cells with either 50 nM noncoding (NC) siRNA or PERK siRNA, followed by treatment with BHPI (n = 4). (H) Western blot analysis showing full-length (p90-ATF6α) and cleaved p50-ATF6α in BHPI-treated cells and effect of BHPI on levels of spliced-XBP1 mRNA (sp-XBP1). (I) BHPI increases intracellular calcium levels. Visualization of intracellular Ca2+ using Fluo-4 AM; BHPI (1 μM) was added to MCF-7 cells at 30 s. Color scale from basal Ca2+ to highest Ca2+: blue, green, red, white. (J) Inhibiting opening of the endoplasmic reticulum IP3R Ca2+ channel abolishes BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis. The ryanodine and IP3R Ca2+ channels were preblocked with 100 μM ryanodine (RyR) and 100 μM 2-amino propyl-benzoate (2-APB), respectively, followed by 70 nM BHPI for 3 h (n = 4). (K) Quantitation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels after treating MCF-7 cells with either 50 nM noncoding (NC) siRNA, pan IP3R siRNA SmartPool, followed by treatment with BHPI (n = 10). IP3R SmartPool contained equal amounts of three individual SmartPools directed against each isoform of IP3R. (L) Effects of BHPI on protein synthesis in MCF-7 cells treated with either 100 nM NC siRNA, pan-IP3R siRNA, or PLCγ siRNA SmartPool (n = 4). (M) Quantitation of intracellular IP3 levels following treatment of MCF-7 cells for 10 min with E2 or BHPI (n = 3). (N) Model of BHPI acting through the UPR, eEF2, and AMPK to kill ERα+ cancer cells. Data are mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate a significant difference among groups (P < 0.05) using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. n.s., not significant.

BHPI Rapidly Inhibits Protein Synthesis by a PLCγ-Mediated Opening of the Inositol Triphosphate Receptor (IP3R) Ca2+ Channel, Activating the PERK Arm of the UPR.

Inhibiting mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling did not strongly inhibit protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S6D), suggesting BHPI is unlikely to work through mTOR. We next investigated whether initial inhibition of protein synthesis by BHPI is due to activation of the UPR. There are three UPR arms. The transmembrane kinase PERK is activated by autophosphorylation. p-PERK phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), inhibiting translation of most mRNAs (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A) (24, 25). The other arms of the UPR initiate with ATF6α activation (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B), leading to increased protein folding capacity and activation of IRE1α, which alternatively splices XBP1, producing active spliced (sp)-XBP1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S7C) (24, 25). In ERα+ MCF-7 and T47D cells, but not in ERα− MDA-MB-231 cells, BHPI rapidly inhibited protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A) and in parallel increased eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 3F and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 B and C). Downstream readouts of eIF2α phosphorylation, CHOP and GADD34 mRNAs, were rapidly induced by BHPI (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 D and E). Consistent with BHPI inhibiting protein synthesis through eIF2α-Ser51 phosphorylation, transfecting cells with a dominant-negative eIF2α-S51A mutant largely prevented BHPI from inhibiting protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S8F). We next evaluated whether increases in eIF2α phosphorylation and rapid inhibition of protein synthesis occur through activation of PERK. p-PERK was increased 30 min after BHPI treatment (Fig. 3F and SI Appendix, Fig. S8G), and pretreating cells with a PERK inhibitor (PERKi) abolished rapid BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). RNAi knockdown of PERK abolished BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis at 30 min and strongly inhibited BHPI-stimulated eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 3G and SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Because PERK knockdown blocks rapid eIF2α phosphorylation, BHPI is not inhibiting translation by activating other upstream kinases that phosphorylate eIF2α. Furthermore, BHPI rapidly activates the ATF6α and IRE1α arms of the UPR, as shown by increased cleaved p50-ATF6α and sp-XBP1 (Fig. 3H).

To explore how BHPI activates the UPR, we examined inhibition of protein synthesis by known UPR activators. Thapsigargin (THG) and ionomycin, which activate the UPR by release of Ca2+ from the lumen of the EnR into the cytosol (24, 25), but not UPR activators that work by other mechanisms, elicited the rapid and near quantitative inhibition of protein synthesis seen with BHPI (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A).

To test whether BHPI alters intracellular Ca2+, we monitored intracellular Ca2+ with the calcium-sensitive dye Fluo-4 AM. In MCF-7 cells, BHPI produced a large and sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ and a large transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ in the absence of extracellular calcium (Fig. 3I, Movie S1, and SI Appendix, Fig. S10B). Time-dependent changes in cytosol calcium in BHPI-treated MCF-7 cells were quantitated (SI Appendix, Fig. S10B). Because BHPI elicits a large increase in cytosol Ca2+ when there is no extracellular Ca2+, BHPI is acting by depleting the Ca2+ store in the EnR. BHPI had no effect on intracellular Ca2+ in ERα− HeLa cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S10C).

We next identified the EnR Ca2+ channel that opens after BHPI treatment. The inositol triphosphate receptor (IP3R) and ryanodine (RyR) receptors are the major EnR Ca2+ channels. Treatment with 2-APB, which locks the IP3R Ca2+ channels closed, but not closing the RyR Ca2+ channels with high concentration ryanodine (Ry), abolished the rapid BHPI–ERα-mediated increase in cytosol Ca2+ and inhibition of protein synthesis (Fig. 3 I and J). Furthermore, RNAi knockdown of IP3R (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A) abolished the BHPI-mediated increase in cytosol Ca2+ and inhibition of protein synthesis (Fig. 3 K and L). IP3R Ca2+ channels are also modulated through protein kinase A (PKA), but BHPI did not induce PKA-dependent IP3R-Ser1756 phosphorylation (26) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B).

BHPI Strongly Activates Phospholipase C γ, Producing Inositol 1,4,5-Triphosphate.

Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) is produced when the activated phosphorylated plasma membrane enzyme, phospholipase C γ (PLCγ), hydrolyzes PIP2 to diacylglycerol (DAG) and IP3. Supporting a role for PLCγ, siRNA knockdown of PLCγ (SI Appendix, Fig. S11C) abolished the BHPI-mediated increase in cytosol Ca2+ (SI Appendix, Fig. S11C) and BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis (Fig. 3L), and the PLCγ inhibitor U73122 abolished the BHPI–ERα increase in cytosol Ca2+ (SI Appendix, Fig. S11C). Confirming PLCγ’s role, BHPI induces rapid PLCγ-Tyr783 phosphorylation (SI Appendix, Fig. S11D), and strongly increased IP3 levels (Fig. 3M). Supporting the idea that BHPI acts by distorting the newly described weak E2–ERα activation of the UPR (14), BHPI induced a much larger increase in IP3 levels than E2 (Fig. 3M).

Rapid BHPI activation of plasma membrane PLCγ indicates UPR activation is an extranuclear action of BHPI–ERα. PLCγ and ERα coimmunoprecipitate (27), and overexpression of ERα in MCF7ERαHA cells further increased IP3 levels in response to BHPI (SI Appendix, Fig. S11E). Consistent with extranuclear ERα-dependent activation of the UPR, an estrogen-dendrimer conjugate (EDC) that cannot enter the nucleus (28), induced sp-XBP1, but not nuclear estrogen-regulated genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). A model depicting BHPI action is presented in Fig. 3N.

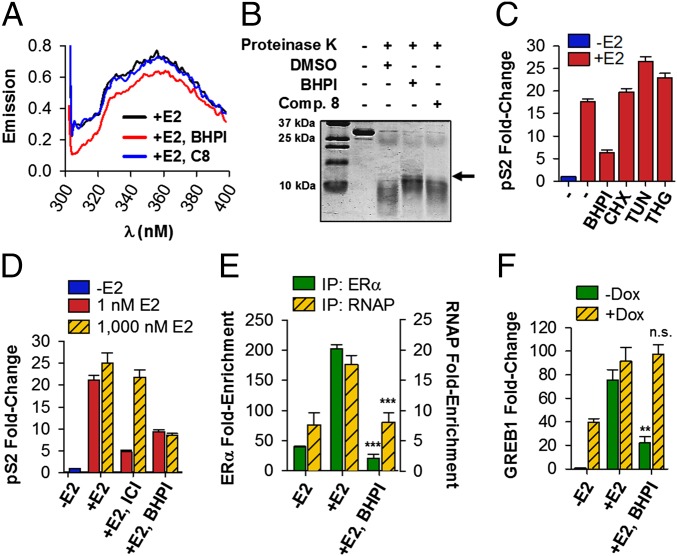

BHPI Inhibits E2–ERα-Regulated Gene Expression and Likely Interacts with ERα.

Consistent with BHPI binding to E2–ERα, BHPI, but not an inactive close relative, compound 8 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), significantly altered the fluorescence emission spectrum of purified ERα (Fig. 4A). We also tested whether BHPI alters the sensitivity of purified ERα ligand-binding domain (LBD) to protease digestion. Addition of BHPI followed by cleavage with proteinase K revealed a 15-kDa band in BHPI-treated ERα LBD that was nearly absent in the LBD treated with DMSO or compound 8 (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

BHPI interacts with ERα and inhibits E2–ERα-regulated gene expression. (A) Fluorescence emission spectra of full-length ERα in the presence of E2 and either DMSO, 500 nM BHPI, or 500 nM of the BHPI-related inactive compound 8 (C8). (B) ERα LBD was subjected to proteinase K digestion in the presence of DMSO vehicle, C8, or BHPI. Bands were visualized by Coomassie staining. (C) qRT-PCR showing pS2 mRNA in MCF-7 cells pretreated for 0.5 h with BHPI, cycloheximide (CHX), tunicamycin (TUN), thapsigargin (THG), or DMSO, followed by treatment with or without E2 for 2 h. (D) BHPI is a noncompetitive ERα inhibitor. qRT-PCR shows pS2 mRNA in MCF-7 cells treated with BHPI or the competitive inhibitor ICI, and low (1 nM) or high (1,000 nM) E2. (E) ChIP showing effect of BHPI on recruitment of E2–ERα (green bars) and RNA polymerase II (RNAP, yellow hatched bars) to the promoter region of pS2. (F) qRT-PCR showing GREB1 mRNA levels in MCF7ERαHA cells after 1 d ± doxycycline (DOX), pretreated for 30 min with BHPI or DMSO, followed by 4 h with or without E2. Concentrations are as follows: E2, 500 nM (A and B), 10 nM (C–F); BHPI, 500 nM (A) or 1 μM (B–F); C8, 500 nM (A) or 1 μM (B); CHX, 10 μM; THG, 1 μM; TUN, 10 μg/mL. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, compared with +E2 samples. n.s., not significant.

Because BHPI interacts with ERα and distorts an extranuclear action of E2–ERα, we tested whether, independent of its ability to inhibit protein synthesis and activate the UPR, BHPI would also modulate nuclear E2–ERα-regulated gene expression. At early times when BHPI inhibited E2–ERα induction of pS2 mRNA, neither inhibiting protein synthesis with cycloheximide (CHX), nor activating the UPR with tunicamycin (TUN) or THG (SI Appendix, Fig. S13A), inhibited induction of pS2 mRNA (Fig. 4C). BHPI inhibited E2–ERα induction of pS2, GREB1, XBP1, CXCL2, and ERE-luciferase in ERα+ MCF-7, and T47D cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S13 B–F) and blocked E2–ERα down-regulation of IL1-R1 and EFNA1 mRNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S13 E and G). BHPI is not a competitive ERα inhibitor. Increasing the concentration of E2 by 1,000-fold had no effect on BHPI inhibition of E2 induction of pS2 mRNA (Fig. 4D). Moreover, BHPI did not compete with E2 for binding to ERα (SI Appendix, Fig. S14A). Because BHPI inhibits E2–ERα induction and repression of gene expression, BHPI acts at the level of ERα and not by a general inhibition or activation of transcription.

BHPI did not alter ERα protein levels or nuclear localization (SI Appendix, Fig. S14 B and C). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) showed that BHPI strongly inhibited E2-stimulated recruitment of ERα and RNA polymerase II to the pS2 and GREB1 promoter regions (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. S14D). Consistent with BHPI inducing an ERα conformation exhibiting reduced affinity for gene regulatory regions, 10-fold overexpression of ERα in MCF7ERαHA cells abolished BHPI inhibition of induction of GREB1 mRNA (Fig. 4F). BHPI still kills these cells because ERα overexpression enhances BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis (Fig. 3E). Taken together, our data provide compelling evidence that BHPI is a new type of biomodulator, altering both nuclear and extranuclear actions of ERα.

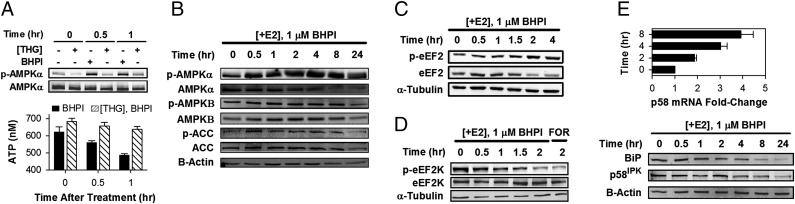

BHPI Rapidly Depletes Intracellular ATP Stores and Activates AMPK.

BHPI treatment results in rapid depletion of EnR Ca2+. To restore EnR Ca2+, the cell activates sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) pumps, which catalyze ATP-dependent transfer of Ca2+ from the cytosol into the lumen of the EnR. Because BHPI opens the IP3R Ca2+ channel, Ca2+ pumped back into the EnR lumen by SERCA flows back into the cytosol (model in Fig. 3N). This futile cycle rapidly depletes intracellular ATP, resulting in activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by AMPKα-Thr172 phosphorylation (Fig. 5 A and B). Moreover, the AMPK target, acetyl CoA-carboxylase (ACC) is rapidly phosphorylated (Fig. 5B). Because thapsigargin, which depletes EnR Ca2+ by inhibiting SERCA pumps, had no effect on ATP levels (Fig. 5A) and did not increase levels of p-AMPKα and p-ACC (SI Appendix, Fig. S15A), ATP depletion, rather than increased cytosol Ca2+, is responsible for AMPK activation. Importantly, preblocking SERCA pumps with thapsigargin abolished the BHPI-induced decline in ATP levels and phosphorylation of AMPKα (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

BHPI depletes intracellular ATP stores, activates AMPK, and inhibits protein synthesis at a second site. (A) Inhibiting SERCA pumps with thapsigargin (THG) prevents BHPI from reducing intracellular ATP levels. Western blot shows effect of THG (1 μM) or BHPI (1 μM) treatment of MCF-7 cells on AMPKα-Thr172 phosphorylation. ATP levels in MCF-7 cells were treated with 1 μM BHPI or 1 μM BHPI and 1 μM THG (n = 5). (B) Western blot analysis of the time course of AMPKα (Thr-172), AMPKβ (Ser-108), and acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC) (Ser-79) phosphorylation in BHPI-treated MCF-7 cells. AMPKα-Thr172 and AMPKβ-Ser108 phosphorylation are required for AMPK activation. (C) Western blot analysis of eEF2 phosphorylation (Thr-56) over time in BHPI-treated ERα+ MCF-7 cells. (D) Western blot analysis showing the time course of decreasing eEF2K (Ser-366) phosphorylation in BHPI-treated MCF-7 cells. Ser-366 dephosphorylation activates eEF2K. (E) qRT-PCR analysis showing changes in p58IPK mRNA and Western blot analysis showing p58IPK and BiP protein after treatment with BHPI (n = 3). −E2 set to 1.

BHPI Blocks UPR Inactivation by Targeting a Second Site of Protein Synthesis Inhibition.

In ERα+, but not ERα− cells, after ∼2 h, BHPI phosphorylates and inactivates eukaryotic elongation factor 2, (eEF2) (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S15 B and C). eEF2 phosphorylation is regulated by a single Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase, eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase (CAMKIII/eEF2K). eEF2K is inhibited by mTORC1-p70S6K and ERK-p90RSK through eEF2K-Ser366 phosphorylation and activated by Ca2+/calmodulin and AMPK (29, 30). BHPI increases cytosol Ca2+ and activates AMPK, but inhibiting AMPK did not inhibit eEF2 phosphorylation (SI Appendix, Fig. S15D). BHPI also rapidly induces a transient increase in ERK1/2 activation (SI Appendix, Fig. S15 E and F), which stimulates ERK-p90RSK and mTORC1-p70S6K activation (31). Together, these pathways induce eEF2K-Ser366 phosphorylation (Fig. 5D) and prevent increases in p-eEF2 for ∼1 h after BHPI treatment (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S15G). Consistent with this mechanism, blocking ERK activation with U0126 prevented BHPI from producing transient declines in eEF2 phosphorylation through inactivation of eEF2K (SI Appendix, Fig. S15G).

UPR activation with conventional UPR activators produces transient eIF2α phosphorylation and inhibition of protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Figs. S15A and S16 A and B) in part because they induce BiP and p58IPK chaperones (SI Appendix, Fig. S16 C and D). The chaperones help resolve UPR stress and inactivate the UPR. In contrast, BHPI blocks induction and reduces levels of BiP and p58IPK protein (Fig. 5E), leading to sustained eIF2α phosphorylation and inhibition of protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S8B). BHPI failed to increase p58 protein despite inducing p58 mRNA (Fig. 5E), and at later times PERK inhibition failed to prevent BHPI from inhibiting protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A). This is consistent with BHPI targeting protein synthesis at a second site at later times.

Discussion

BHPI and estrogen share the same ERα-dependent pathway for UPR activation: activation of PLCγ producing IP3, opening of the IP3R Ca2+ channels, release of EnR Ca2+, and activation of the PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6α arms of the UPR (model in Fig. 3N). We recently reported that as an early component of the proliferation program, E2–ERα weakly and transiently activates the UPR. We showed that E2–ERα elicits a mild and transient activation of the PERK arm of the UPR, while simultaneously increasing chaperone levels and protein folding capacity by activating the IRE1α and ATF6α arms of the UPR (14). BHPI distorts this normal action of E2–ERα by increasing the amplitude and duration of UPR activation. Compared with E2, BHPI hyperactivates PLCγ, producing much higher IP3 levels, Ca2+ release from the EnR, and UPR activation. BHPI initially inhibits protein synthesis by strongly activating the PERK arm of the UPR. Knockdown of ERα, PLCγ, IP3R, and PERK blocked rapid BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis. Whereas BHPI activates the IRE1α and ATF6α UPR arms, by acting at later times to inhibit protein synthesis at a second site, BHPI prevents the synthesis of chaperones required to inactivate the UPR. Because the cell attempts to restore EnR Ca2+ while the IP3R Ca2+ channels remain open, BHPI rapidly depletes ATP (Fig. 3N), resulting in activation of AMPK. Several actions of BHPI, including strong elevation of intracellular calcium, sustained UPR activation, long-term inhibition of protein synthesis, ATP depletion, and AMPK activation can potentially contribute to BHPI’s ability to block cell proliferation. How the cascade of events initiated by BHPI enables BHPI to block cell proliferation, and often kill, ERα+ cancer cells requires further exploration. Supporting BHPI targeting PLCγ and the UPR through ERα, independent of its effects on the UPR, BHPI inhibits E2–ERα-mediated induction and repression of gene expression.

BHPI and E2 activation of plasma membrane-bound PLCγ, resulting in increased IP3, is an extranuclear action of ERα. Increasing the level of ERα increased IP3 levels. Consistent with ERα and PLCγ interaction, they coimmunoprecipitate (27). BHPI and E2 induce Ca2+ release in 1 min, too rapidly for action by regulating nuclear gene expression (14). Furthermore, a membrane-impermeable estrogen-dendrimer induces the UPR marker sp-XBP1, but not nuclear E2–ERα-regulated genes.

The UPR plays important roles in tumorigenesis, therapy resistance, and cancer progression (14, 32). Moderate and transient UPR activation by E2 and other activators promotes an adaptive stress response, which increases UPR expression and confers protection from subsequent exposure to higher levels of cell stress (14, 33). In contrast, sustained UPR activation triggers cell death. Because most current anticancer drugs inhibit a pathway or protein important for tumor growth or metastases, most UPR targeting efforts focus on inactivating a protective stress response by inhibiting UPR components (34). UPR overexpression in cancer is associated with a poor prognosis (14), suggesting that sustained lethal hyperactivation of the UPR by BHPI represents a novel alternative anticancer strategy.

BHPI can selectively target cancer cells, because its targets, ERα and the UPR, are both overexpressed in breast and ovarian cancers (14, 22, 32, 35). Cells expressing low levels of ERα, more typical of nontransformed ERα-containing cells, such as PC-3 prostate cancer cells, were less sensitive to BHPI inhibition of protein synthesis (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), whereas doxycycline-treated MCF7ERαHA cells expressing very high levels of ERα exhibited near complete inhibition of protein synthesis (Fig. 3E). Consistent with low toxicity, in the xenograft study, BHPI-treated mice showed no evidence of gross toxicity.

Most gynecological cancers show little dependence on estrogens for growth, and other noncompetitive ERα inhibitors have not demonstrated effectiveness in these cells. BHPI is highly effective in several breast and ovarian cancer drug-resistance models and extends the reach of ERα biomodulators to gynecologic cancers that do not respond to current endocrine therapies. BHPI’s effectiveness in ERα-containing breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer cells is consistent with the finding that female reproductive cancers exhibit common genetic alterations and might respond to the same drugs (36) and with our finding that E2–ERα weakly activates the UPR in breast and ovarian cancer cells (14).

With its submicromolar potency, effectiveness in a broad range of therapy-resistant cancer cells, ability to induce substantial tumor regression, and unique mode of action, BHPI is a promising small molecule for therapeutic evaluation and mechanistic studies.

Materials and Methods

Additional methods are in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture and Reagents, Chemical Libraries, Screening, IP3 Assays, Luciferase Assays, qRT-PCR, ChIP, Transfections, and in Vitro Binding Assays.

Techniques are further described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Calcium Imaging.

Cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations were measured using the calcium-sensitive dye, Fluo-4 AM (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods).

Protein Synthesis.

Protein synthesis rates were evaluated by measuring incorporation of 35S-methionine into newly synthesized protein (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods).

Mouse Xenograft.

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. The MCF-7 cell mouse xenograft model has been described previously (19), and studies were performed as described in SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

Calcium measurements are reported as mean ± SE. All other pooled measurements are represented as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student t tests or one-way ANOVA with post hoc Fisher’s least significant difference tests were used for statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. Zhang [University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign (UIUC)’s High-Throughput Screening facility] for advice; Dr. S. Mattick (UIUC’s Cell Media facility) for media; Mr. J. Hartman for assistance with xenografts; Dr. J. Katzenellenbogen, Dr. S. H. Kim, and Ms. K. Carlson for supplying the estrogen dendrimer conjugate and performing ER binding assays; Drs. E. Wilson and K. Korach, B.-H. Park, E. Alarid, and R. Schiff for cell lines; and Drs. M. Glaser, M. Barton, and C. Zhang for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01 DK 071909 and the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (DOD BCRP) BC131871 (to D.J.S.), P50AT006268 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the Office of Dietary Supplements and the National Cancer Institute (to W.G.H.), a DOD BCRP predoctoral fellowship (to M.M.C.), and Westcott and Carter predoctoral fellowships (to N.D.A.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have filed a patent application on BHPI.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.H. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1403685112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Deroo BJ, Korach KS. Estrogen receptors and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):561–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI27987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musgrove EA, Sutherland RL. Biological determinants of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(9):631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrc2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tyson JJ, et al. Dynamic modelling of oestrogen signalling and cell fate in breast cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(7):523–532. doi: 10.1038/nrc3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu KD, Wu J, Shen ZZ, Shao ZM. Hazard of breast cancer-specific mortality among women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer after five years from diagnosis: Implication for extended endocrine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):E2201–E2209. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emons G, et al. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie (AGO) Phase II study of fulvestrant 250 mg/month in patients with recurrent or metastatic endometrial cancer: A study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129(3):495–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpkins F, et al. Src Inhibition with saracatinib reverses fulvestrant resistance in ER-positive ovarian cancer models in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(21):5911–5923. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smyth JF, et al. Antiestrogen therapy is active in selected ovarian cancer cases: The use of letrozole in estrogen receptor-positive patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(12):3617–3622. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemal A, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101(1):3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benod C, et al. Structure-based discovery of antagonists of nuclear receptor LRH-1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(27):19830–19844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.411686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kretzer NM, et al. A noncompetitive small molecule inhibitor of estrogen-regulated gene expression and breast cancer cell growth that enhances proteasome-dependent degradation of estrogen receptor alpha. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(53):41863–41873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.183723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiruchelvam PT, et al. The liver receptor homolog-1 regulates estrogen receptor expression in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127(2):385–396. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0994-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang LH, et al. Disruption of estrogen receptor DNA-binding domain and related intramolecular communication restores tamoxifen sensitivity in resistant breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2006;10(6):487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andruska N, Mao C, Cherian M, Zhang C, Shapiro DJ. Evaluation of a luciferase-based reporter assay as a screen for inhibitors of estrogen-ERα-induced proliferation of breast cancer cells. J Biomol Screen. 2012;17(7):921–932. doi: 10.1177/1087057112442960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andruska N, Zheng X, Yang X, Helferich WG, Shapiro DJ. Anticipatory estrogen activation of the unfolded protein response is linked to cell proliferation and poor survival in estrogen receptor α-positive breast cancer. Oncogene. 2014 doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rimawi MF, et al. Reduced dose and intermittent treatment with lapatinib and trastuzumab for potent blockade of the HER pathway in HER2/neu-overexpressing breast tumor xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(6):1351–1361. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohta T, et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase increases efficacy of cisplatin in in vivo ovarian cancer models. Endocrinology. 2006;147(4):1761–1769. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali AY, Abedini MR, Tsang BK. The oncogenic phosphatase PPM1D confers cisplatin resistance in ovarian carcinoma cells by attenuating checkpoint kinase 1 and p53 activation. Oncogene. 2012;31(17):2175–2186. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergara D, et al. Lapatinib/Paclitaxel polyelectrolyte nanocapsules for overcoming multidrug resistance in ovarian cancer. Nanomedicine (Lond Print) 2012;8(6):891–899. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ju YH, Doerge DR, Allred KF, Allred CD, Helferich WG. Dietary genistein negates the inhibitory effect of tamoxifen on growth of estrogen-dependent human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells implanted in athymic mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62(9):2474–2477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong H, et al. Antitumor activity of targeted and cytotoxic agents in murine subcutaneous tumor models correlates with clinical response. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(14):3846–3855. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abukhdeir AM, et al. Tamoxifen-stimulated growth of breast cancer due to p21 loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(1):288–293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710887105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fowler AM, Solodin NM, Valley CC, Alarid ET. Altered target gene regulation controlled by estrogen receptor-alpha concentration. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(2):291–301. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikeda Y, et al. Estrogen regulates hepcidin expression via GPR30-BMP6-dependent signaling in hepatocytes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(7):519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334(6059):1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeSouza N, et al. Protein kinase A and two phosphatases are components of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor macromolecular signaling complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(42):39397–39400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li T, et al. SH2D4A regulates cell proliferation via the ERalpha/PLC-gamma/PKC pathway. BMB Rep. 2009;42(8):516–522. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2009.42.8.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington WR, et al. Estrogen dendrimer conjugates that preferentially activate extranuclear, nongenomic versus genomic pathways of estrogen action. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(3):491–502. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leprivier G, et al. The eEF2 kinase confers resistance to nutrient deprivation by blocking translation elongation. Cell. 2013;153(5):1064–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Proud CG. Signalling to translation: How signal transduction pathways control the protein synthetic machinery. Biochem J. 2007;403(2):217–234. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121(2):179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo B, Lee AS. The critical roles of endoplasmic reticulum chaperones and unfolded protein response in tumorigenesis and anticancer therapies. Oncogene. 2013;32(7):805–818. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutkowski DT, et al. Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(11):e374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healy SJ, Gorman AM, Mousavi-Shafaei P, Gupta S, Samali A. Targeting the endoplasmic reticulum-stress response as an anticancer strategy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625(1-3):234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thorpe SM, Christensen IJ, Rasmussen BB, Rose C. Short recurrence-free survival associated with high oestrogen receptor levels in the natural history of postmenopausal, primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A(7):971–977. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kandoth C, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497(7447):67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.