Significance

Many mechanisms of the Cambrian Explosion have been proposed, but rigorous quantitative analyses of biodiversity dynamics are scarce, although they may shed light on important factors. Using a comprehensive database and sampling standardization, we dissect global diversity patterns. The trajectories of within-community, between-community, and global diversity during the main phase of the Cambrian radiation revealed a low-competition model, which was probably governed by niche contraction and the increase of predation at local scales. At continental scales, the increase of beta diversity was controlled by the high rate of community turnover among adjacent continents. This finding supports the general importance of plate tectonics in large-scale diversifications.

Keywords: Cambrian radiation, alpha diversity, beta diversity, low competition, Pannotia

Abstract

The fossil record offers unique insights into the environmental and geographic partitioning of biodiversity during global diversifications. We explored biodiversity patterns during the Cambrian radiation, the most dramatic radiation in Earth history. We assessed how the overall increase in global diversity was partitioned between within-community (alpha) and between-community (beta) components and how beta diversity was partitioned among environments and geographic regions. Changes in gamma diversity in the Cambrian were chiefly driven by changes in beta diversity. The combined trajectories of alpha and beta diversity during the initial diversification suggest low competition and high predation within communities. Beta diversity has similar trajectories both among environments and geographic regions, but turnover between adjacent paleocontinents was probably the main driver of diversification. Our study elucidates that global biodiversity during the Cambrian radiation was driven by niche contraction at local scales and vicariance at continental scales. The latter supports previous arguments for the importance of plate tectonics in the Cambrian radiation, namely the breakup of Pannotia.

Whittaker (1) decomposed regional (gamma) diversity into local (alpha) and turnover (beta) components. Although this concept is widely used and the principal levels of biodiversity are well explored in time and space, there are few analyses on the relationship of alpha and beta diversity in deep time during major evolutionary radiations. The potential of Whittaker’s concept to provide insights into evolutionary processes has been demonstrated in a few paleobiologic studies (e.g., refs. 2 and 3). The question as to how the Cambrian radiation was partitioned within and between communities is old (4), and not resolved. The Cambrian Explosion has been characterized as the rapid increase of both biodiversity and morphological disparity (5–7). The causes of this unique evolutionary radiation have been suggested to be abiotic (8), ecologic (9, 10), and genetic (5, 11) factors and their complex interplay (12, 13). Here, we derive potential triggers of the Cambrian radiation from the way diversity was partitioned geographically and environmentally during the main diversification phase.

We use sampling-standardized analyses of fossil occurrence data from the Paleobiology Database to derive accurate time series of alpha, beta, and gamma diversity from the Ediacaran into the earliest Ordovician. Gamma diversity is understood as global genus richness, whereas beta diversity is used to characterize turnover between individual assemblages as well as depositional environments or geographic areas (Materials and Methods). We test whether the Cambrian increase in gamma diversity was preferentially governed by beta or alpha diversity. We also separated environmental and geographic beta to identify the main driver of beta diversity. Environmental beta measures faunal dissimilarity between different habitats, whereas geographic beta (also termed geodisparity; ref. 14) measures faunal dissimilarity between different geographic regions. The relationship of alpha and beta diversity during the main diversification interval in the early Cambrian is assessed as a function of global diversity, which can elucidate underlying processes (15).

Results

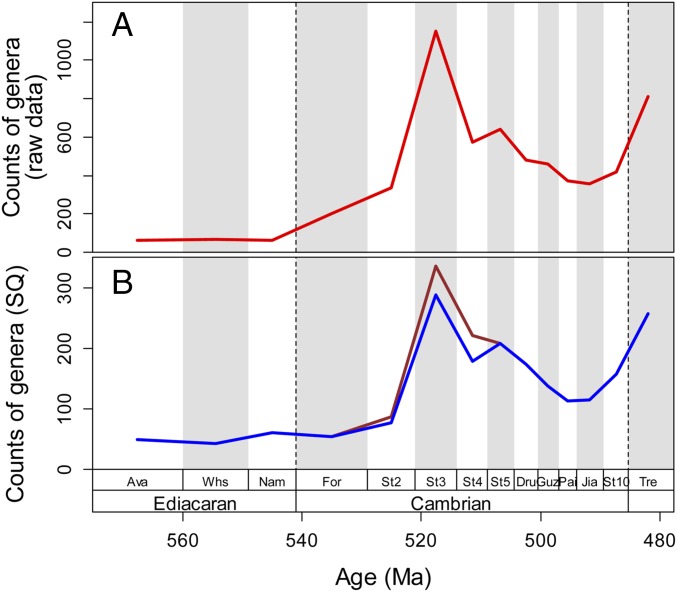

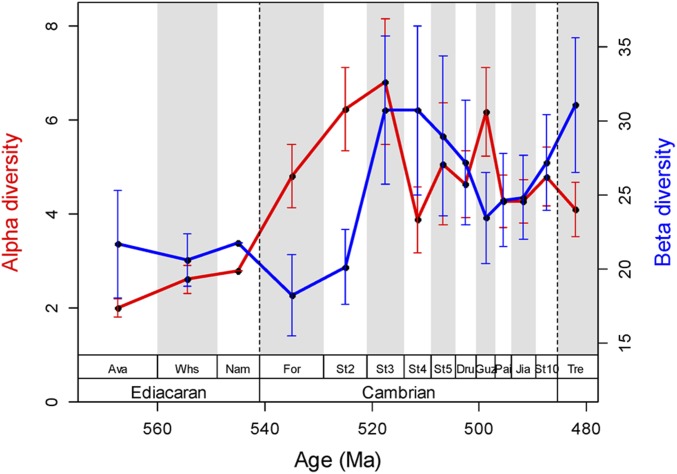

Raw gamma diversity exhibits a strong increase in the first three Cambrian stages (informally referred to as early Cambrian in this work) (Fig. 1A). Gamma diversity dropped in Stage 4 and declined further through the rest of the Cambrian. The pattern is robust to sampling standardization (Fig. 1B) and insensitive to including or excluding the archaeocyath sponges, which are potentially oversplit (16). Alpha and beta diversity increased from the Fortunian to Stage 3, and fluctuated erratically through the following stages (Fig. 2). Our estimate of alpha (and indirectly beta) diversity is based on the number of genera in published fossil collections and, thus, may be affected by monographic biases. However, the same basic pattern is seen in diversity estimates of paleocommunities with abundance data (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Global genus-level diversity of marine animals from the Ediacaran to the earliest Ordovician. (A) Raw counts of the number of genera (sampled-in-bin). Note log scale of y axis. (B) Sampling-standardized genus-level diversity (sampled-in-bin) based on shareholder quorum subsampling with 70% frequency coverage per stage. The brown line refers to all marine genera, and the blue line excludes archaeocyaths. Ma, million years ago. Ava, Avalon assemblage; Dru, Drumian; For, Fortunian; Guz, Guzhangian; Jia, Jiangshanian; Nam, Nama assemblage; Pai, Paibian; St2, Stage 2; St3, Stage 3; St4, Stage 4; St5, Stage 5; St10, Stage 10; Tre, Tremadocian (Ordovician) Whs, White Sea assemblage.

Fig. 2.

Alpha diversity and beta diversity from the Ediacaran to the earliest Ordovician based on unweighted by-list subsampling of 45 collections per stage. Error bars are SDs of 100 subsampling trials.

Beta diversity can be biased by the variation of geographic clustering among sites over time. Therefore, we test the correlation between the median paleogeographic distance of collections and beta diversity, as well as between the median distance of grid centroids and beta diversity. There is no significant correlation in both cases (median distance between collections/beta: ρ = 0.1, P = 0.727; median distance between grid centroids/beta: ρ = −0.24, P = 0.418), implying that geographic clustering does not cause a significant bias.

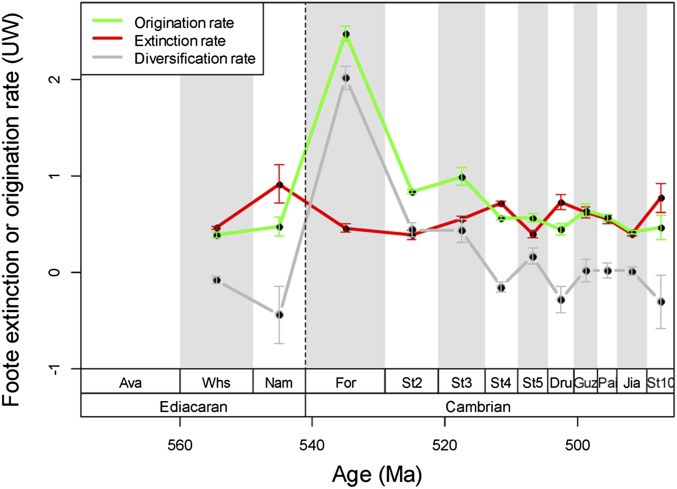

Mass extinctions may affect diversity at multiple levels. Several episodes of profound turnover and mass extinction have been noted at the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary and throughout the Cambrian (17, 18). Our sampling-standardized analysis confirms high extinction rates throughout the Cambrian (Fig. 3). There is no significant correlation between extinction rates and either alpha or beta diversity (extinction rate/alpha: ρ = −0.35, P = 0.266; extinction rate/beta: ρ = 0.287, P = 0.366), indicating that the observed extinctions are unlikely to introduce a substantial bias on alpha-beta-gamma diversity patterns.

Fig. 3.

Sampling-standardized extinction and origination rates through the Ediacaran and Cambrian. Rates are per-capita rates of Foote (70) but not standardized by stage durations (71). Error bars are SDs of 100 subsampling trials.

We find a strong correlation between global genus richness and beta diversity (ρ = 0.93, P < 0.001), whereas there is no significant correlation between global genus richness and alpha diversity (ρ = 0.42, P = 0.137). The same relationship is evident with a moving-window approach of five successive stages (Fig. S2). Here the beta-gamma link is significant over the interval from Stage 2 to the Drumian. The strong correlation between beta diversity and gamma diversity could be biased by the multiplicative approach we are using to derive beta diversity from both alpha and gamma diversity, which are independently assessed (Materials and Methods). Although this method probably has a better biological underpinning than the additive approach (15), a correlation between gamma and beta diversity is still evident when using an additive method (ρ = 0.84, P < 0.001). Therefore, gamma diversity in the Cambrian was largely governed by differentiation among communities or assemblages rather than by genus packing within assemblages.

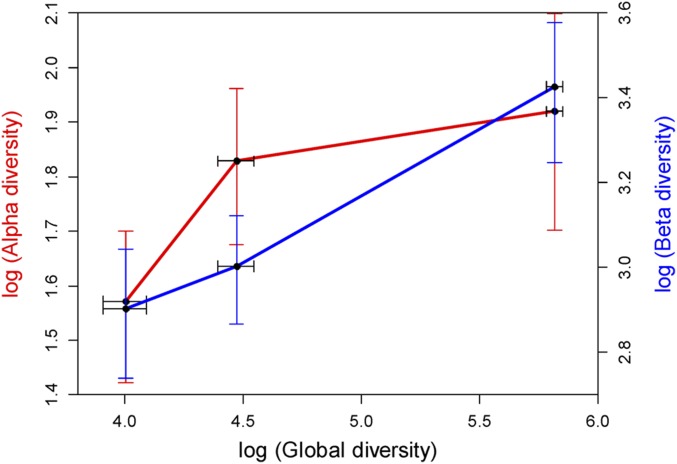

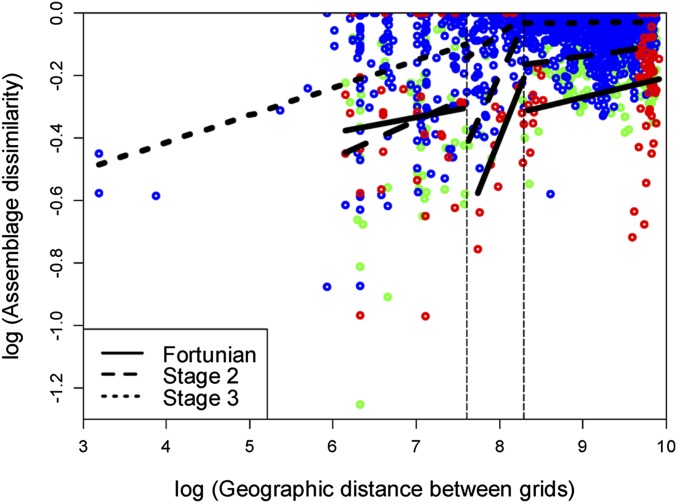

An alpha-beta-gamma plot during the time of unconstrained diversification, that is, in the first three Cambrian stages, reveals that alpha diversity initially increased faster than beta diversity, but subsequently, beta diversity increased more rapidly (Fig. 4). This pattern is predicted for a low-competition scenario (15). The pattern of beta diversity is similar for environmental and geographic beta, which both increased during the first three stages and then stabilized (Fig. S3). This finding suggests that taxonomic gradients among habitats and geographic regions were equally important. To disentangle geographic turnover, we assess geodisparity in three spatial intervals of paleogeographic distance among 5 × 5° paleogeographic grids. The result shows (Fig. 5) that turnover in assemblage composition increased gradually with paleogeographic distance in the intervals of less than 2,000 km and greater than 4,000 km, likely reflecting normal Cambrian distance-decay patterns (19). However, turnover in the 2,000- to 4,000-km interval increased dramatically with geographic distance (Table S1), and this spatial interval is the distance typically measured between adjacent paleo-continents in the early Cambrian (Fig. S4). Plate-tectonic configuration in the early Cambrian is poorly constrained (20), but the Neoproterozoic formation of Gondwana is well established (21, 22). Beta diversity within Gondwana shows more muted fluctuations than global beta diversity. Subtracting the global beta from Gondwana beta reveals a major increase in Stage 3 (Fig. S5). Because this increase is concurrent with the main increase of gamma diversity, geodisparity appears to be the main driver of the Cambrian diversity peak.

Fig. 4.

Alpha-beta-gamma plot for the first three Cambrian stages, the time of continuous diversification. Note log scale of all axes.

Fig. 5.

Distance-decay curves during the first three Cambrian stages plotted as taxonomic dissimilarity among 5 × 5° paleogeographic grids. Blue circles, Stage 3; green circles, Stage 2; red circles, Fortunian. The black lines denote separate regressions for three distance intervals.

Finally, although we binned all fossil collections into the currently recognized Ediacaran assemblages and Cambrian stages (Materials and Methods), the Cambrian timescale remains in flux (e.g., ref. 23). This problem raises the question whether our results might change with further revisions of the timescale. We therefore tested how the changes in international correlations and calibrations over the last 20 y have affected the basic results. Binning our data to the traditional Siberian subdivision of the Early Cambrian and lumping all Ediacaran assemblages, as well as Middle and Late Cambrian stages (24), shows some differences such as an extended peak in gamma diversity in the Atdabanian and Botomian, but the basic patterns are robust (Fig. S6): Gamma diversity peaked in the late Early Cambrian, alpha diversity exhibits a profound increase until the Atdabanian, and beta diversity lagged behind alpha diversity in the earliest Cambrian and then caught up.

Discussion

Although a surprising diversity of benthic organisms is now known from the Ediacaran (7), diversity was substantially lower at the gamma and alpha level than in the Cambrian (Figs. 1 and 2). The high taxonomic turnover recognized at the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition (Fig. 3) that marks the disappearance of Ediacaran soft-bodied organisms may be tempered by secular variation in global taphonomic regimes (25), but can also be attributed to ecosystem engineering and predation (26). Environmental perturbations were invoked to explain the extinction of the few skeletal organisms (27).

That the main pulse of the Cambrian radiation was in the early Cambrian has long been known (28, 29), but defining the time of peak diversity has been hampered by problems with stratigraphic correlations. Our improved data and updated stratigraphic assignments demonstrate a pronounced origination and diversification pulse in the earliest Cambrian (Fig. 3). This pulse may be exaggerated by the closure of the Ediacaran taphonomic window with widespread soft-body preservation and the opening of a novel taphonomic window by the widespread acquisition of skeletons (30). Cambrian diversity rose to a prominent peak in Stage 3, which is roughly equivalent to the Siberian Atdabanian and most of the Siberian Botomian (31). The subsequent decline in global diversity may have been partly due to the Sinsk extinction event in Stage 4 (32–34), but environmental factors are more plausible to explain the lack of further diversification in the later Cambrian. For example, prolonged tropical warming has been suggested to explain the scarcity of metazoan reefs in the later Cambrian (35) and would also fit the gamma diversity trajectories given that cooling is thought to have facilitated the subsequent Ordovician radiation (36). Alternatively, a late Cambrian rise in oxygen levels has been proposed to explain the onset of the Ordovician radiation (37). By inference, oxygen limitation may have hindered further diversification after the early Cambrian.

The relationship between alpha and beta diversity during the time of unbounded diversification (Fig. 4) suggests that a low-competition model (15) best explains the Cambrian radiation. When competition is low, the addition of new species to a community happens either by exploitation of previously unused resources or by packing more species in marginal ecospace (38). This process will initially not shrink niches of preexisting taxa such that alpha diversity will increase steeply, whereas beta diversity will initially increase only moderately. As diversification continues, competition will increase, niches will contract, and consequently beta diversity will increase profoundly, whereas alpha diversity levels off. Niche contraction facilitates niche partitioning and, thus, changes of taxonomic composition among habitats. Predation is a potential factor for keeping the system in a low-competition mode (39). Predation is first recognized in the latest Ediacaran (40, 41) and well-documented in the early Cambrian (42, 43). Apex predators are first common in Cambrian Stage 3 (44, 45). Therefore, escalation is a plausible trigger of the Cambrian radiation in terms of both biomineralization (46, 47) and community ecology (48). Predation universally defeats competition in benthic marine systems (49), suggesting that the Cambrian radiation was not exceptional in this aspect.

We show that the increase in beta diversity was the principal driver of increasing gamma diversity during the Cambrian radiation. The pivotal role of beta diversity in structuring global diversity patterns has also been suggested for early Cambrian reef communities (50). Beta diversity strongly depends on both the sizes of sampling area and sampling units (51). In our case, local community differentiation was driven largely by niche contraction. However, at regional or continental scales, beta diversity or community differentiation between regions does not necessarily increase when niches contract, because environmental gradients can be strongly interrupted by dispersal limitation and topographic isolation. Therefore, there must be other factors that drive beta diversity at continental scales in the Cambrian. The steep distance decay in the 2,000- to 4,000-km distance interval (connecting adjacent continents or distant parts of Gondwana; Fig. S4) suggests that the continents became biogeographically distinct in the first two Cambrian stages, and that deep oceans between continental shelf areas caused effective migration barriers, which likely enhanced allopatric speciation (52).

In summary, the drivers of beta diversity varied with spatial scale: (i) at local scales, an increase of beta diversity was due to niche contraction, which, in turn, may have been fueled by predation; and (ii) at continental scales, beta diversity was governed by the strong increase of provincialism among paleo-continents. This increase was accompanied by profound continental reconfigurations often referred to as the breakup of the supercontinent Pannotia (20, 53). Pannotia assembled in the interval from 650 to 550 Ma (54). Its breakup was characterized by the opening of the Iapetus and Ægir oceans (55), resulting in the separation of Laurentia, Baltica, Siberia, and Gondwana, but also orogenies leading to the amalgamation of distinct cratonic blocks within Gondwana. The disassembly of Pannotia (particularly the separation between Laurentia and Gondwana) is suggested to have started close to the onset of the Cambrian radiation (Fortunian; ∼541 Ma) and ended before Cambrian Stage 3 (∼521 Ma) (20). This rapid disassembly of Pannotia corresponds well with the increase of geodisparity (Fig. 5).

Although the breakup of Pannotia is sometimes discussed as a potential trigger of the Cambrian radiation (54), the concept is not widely used. However, our results support the contention that the disassembly of Pannotia increased geodisparity and, thereby, beta and gamma diversity in the Cambrian. Disassembly of supercontinents is rare and always seems to have profound evolutionary consequences. Examples are (i) the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia some 750 Myr ago has been linked with global glaciations, which are often held responsible for the emergence of metazoans (56); (ii) further continental dispersal in the Ordovician is thought to have facilitated the Ordovician diversification (57); and (iii), the link between the breakup of Pangea in the Early Jurassic and the Mesozoic-Cenozoic radiation has long been suggested (58) and is supported by sampling-standardized diversity curves (59).

Alternatively, the capacity of biological dispersal could have changed substantially in the early Cambrian. Our knowledge of dispersal in Ediacaran biota is limited but at least some Ediacaran taxa were able to cross oceanic basins and achieve a cosmopolitan distribution (26, 60). Cambrian animals probably dispersed with nonplanktotrophic larval stages (61), which would limit their geographic distribution relative to animals with planktotrophic larvae (62). Therefore, the increase of geodisparity we observe during the early Cambrian could be due to the widespread appearance of animals with larval stages combined with continental disassembly. In other words, biological innovation—the evolution of larval stages (61)—in tandem with supercontinent breakup best explains the increase of geographic beta diversity. Our study provides evidence for niche partitioning, plate tectonics, and key innovations as strong and persistent evolutionary forces, and the Cambrian radiation is no exception, although it was more substantial in quality than later radiations. Future work should explore the links between the ecological dynamics described here and the astonishing increase of morphological disparity in the early Cambrian.

Materials and Methods

Data.

Fossil occurrence data of Ediacaran to Tremadocian age were entered into the Paleobiology Database (PaleobioDB; paleobiodb.org) and downloaded alongside all other occurrences on May 23, 2014. This dataset comprises 7,117 collections and 39,737 taxonomic occurrences. We assigned each collection to one of 14 stages based on the three widely recognized assemblages in the Ediacaran (63), the 10 stage subdivision of the Cambrian period according to the 2012 International Commission on Stratigraphy time scale (31), and the Tremadocian of the Ordovician (SI Materials and Methods, Fig. S7, and Table S2).

Plate tectonic configurations and paleopositions of fossil occurrences are based on Scotese’s paleomap software (64). Paleopositions were automatically provided upon download of the occurrences from the PaleobioDB. The concept of Pannotia is implemented in Scotese’s reconstructions, and although newer reconstructions differ in some aspects such as the degree of continental dispersal in the earliest Cambrian, they agree in that the Early Cambrian was a time of continental disassembly (SI Materials and Methods).

Diversity Estimation.

To account for sampling heterogeneity (65), diversity has been estimated with sampling standardization. Sampling standardization can be achieved with random draws of the same number of fossil collections, taxonomic occurrences, or a fixed sum of frequency of genus abundance in each time interval (59, 66). We generally assessed diversity by counting taxa actually sampled in an interval (sampled-in-bin, SIB) and, thus, did not interpolate taxon occurrences between their first and last appearance in the fossil record. This counting method has the advantage that edge effects at the beginning and end of time series are avoided (59). We used shareholder quorum subsampling (66) with a quorum of 70% to estimate gamma diversity. Alpha and beta diversity as well as extinction and origination rates were assessed by drawing 45 taxonomic collections at random (by-list unweighted method; UW) (67) and averaging results across 100 subsampling trials.

Alpha diversity was estimated as the number of genera found in a collection, where a collection can vary from a small sample taken from a single bed to a whole formation at a regional scale. To test whether this approach biases our estimate of alpha, we have also measured alpha diversity in the subset of collections for which specimen abundances are provided. We used the Shannon–Wiener Index (68) for those collections that reported at least 80 specimens.

We use two commonly used measures of beta diversity: (i): , where is total diversity at global scales, and is the mean genus richness within assemblages. This metric is a global measure of beta diversity based on presence-absence data (1, 38); and (ii), a pairwise dissimilarity measure based on the Bray–Curtis index (69), which assesses the pairwise dissimilarity among sampling units with respect to environmental or geographic variables.

Environmental beta was measured by pooling collections in the same basic environmental setting and comparing the faunas between environments that differed by one, two, or three environmental categories. Environmental beta is thus estimated by the mean dissimilarity in the context of habitat disparity. Environmental categories were tropical/nontropical (separated at 30° absolute paleolatitude), carbonate/siliciclastic (distinguished by dominant lithology, marls were ignored), and shallow-water/deep-water (separated by storm wave base).

Geographic beta was estimated in the context of paleogeographic distance. To create a paleogeographic distance matrix, we applied the geodisparity method introduced by Miller et al. (14). Occurrence data for a given stratigraphic interval were pooled in 5 × 5° paleogeographic grids. A dissimilarity matrix of these pooled data was computed, and the data were then parsed into 2,000-km intervals of great circle distances between grid centers. We focused on three geographic scales: within a continent (0–2,000 km), between adjacent continents or within a larger continent (2,000-4,000 km), and between remote continents (greater than 4,000 km). The turnover, or the rate of change in community composition, is represented by the slope of the relationship between dissimilarity and geographic distance. This distance–decay relationship was estimated by linear regression (Table S1).

Statistical Tests.

All statistical tests are nonparametric applying Spearman’s rho (ρ). Time-series data were tested for autocorrelations before performing correlation tests. Because there are no significant autocorrelations in any of the relevant variables (alpha, beta, gamma, extinction rate), correlations are based on nondifferenced data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Uta Merkel, Mihaela-Cristina Krause, and all of the other contributors for Ediacaran-Cambrian data entry to Paleobiology Database. We also thank Qi-Jian Li (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg) for valuable suggestions. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft KI 806/9-1, embedded in the Research Unit “The Precambrian-Cambrian Biosphere (R)evolution: Insights from Chinese Microcontinents” (FOR 736). We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. This work is Paleobiology Database Publication No. 225.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.H.E. is a Guest Editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1424985112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Whittaker RH. Vegetation of the Siskiyou Mountains, Oregon and California. Ecol Monogr. 1960;30(3):279–338. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harper DAT. The Ordovician biodiversification: Setting an agenda for marine life. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclim Palaeocl. 2006;232(2-4):148–166. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller AI. A new look at age and area: The geographic and environmental expansion of genera during the Ordovician Radiation. Paleobiology. 1997;23(4):410–419. doi: 10.1017/s0094837300019813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sepkoski JJ., Jr Alpha, beta, or gamma: Where does all the diversity go? Paleobiology. 1988;14(3):221–234. doi: 10.1017/s0094837300011969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erwin DH, et al. The Cambrian conundrum: Early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science. 2011;334(6059):1091–1097. doi: 10.1126/science.1206375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knoll AH, Carroll SB. Early animal evolution: Emerging views from comparative biology and geology. Science. 1999;284(5423):2129–2137. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erwin DH, Valentine JW. The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity. Roberts and Company; Greenwood Village, Colorado: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sperling EA, et al. Oxygen, ecology, and the Cambrian radiation of animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(33):13446–13451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312778110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erwin DH, Tweedt S. Ecological drivers of the Ediacaran-Cambrian diversification of Metazoa. Evol Ecol. 2012;26(2):417–433. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters SE, Gaines RR. Formation of the ‘Great Unconformity’ as a trigger for the Cambrian explosion. Nature. 2012;484(7394):363–366. doi: 10.1038/nature10969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker ME. The genetic response to Snowball Earth: Role of HSP90 in the Cambrian explosion. Geobiology. 2006;4(1):11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall CR. Explaining the Cambrian “explosion” of animals. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2006;34:355–384. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith MP, Harper DAT. Earth science. Causes of the Cambrian explosion. Science. 2013;341(6152):1355–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.1239450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller AI, et al. Phanerozoic trends in the global geographic disparity of marine biotas. Paleobiology. 2009;35(4):612–630. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hautmann M. Diversification and diversity partitioning. Paleobiology. 2014;40(2):162–176. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sepkoski JJ., Jr A kinetic model of Phanerozoic taxonomic diversity II. Early Phanerozoic families and multiple equilibria. Paleobiology. 1979;5(3):222–251. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bambach RK, Knoll AH, Wang SC. Origination, extinction, and mass depletions of marine diversity. Paleobiology. 2004;30(4):522–542. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu MY, Babcock LE, Peng SC. Advances in Cambrian stratigraphy and paleontology: Integrating correlation techniques, paleobiology, taphonomy and paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Palaeoworld. 2006;15(3-4):217–222. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nekola JC, White PS. The distance decay of similarity in biogeography and ecology. J Biogeogr. 1999;26(4):867–878. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalziel IWD. Cambrian transgression and radiation linked to an Iapetus-Pacific oceanic connection? Geology. 2014;42(11):979–982. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meert JG, VanderVoo R. The assembly of Gondwana 800-550 Ma. J Geodyn. 1997;23(3-4):223–235. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meert JG, Lieberman BS. The Neoproterozoic assembly of Gondwana and its relationship to the Ediacaran–Cambrian radiation. Gondwana Res. 2008;14(1):5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landing E, Geyer G, Buchwaldt R, Bowring SA. Geochronology of the Cambrian: A precise Middle Cambrian U–Pb zircon date from the German margin of West Gondwana. Geol Mag. 2015;152(01):28–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grotzinger JP, Bowring SA, Saylor BZ, Kaufman AJ. Biostratigraphic and geochronologic constraints on early animal evolution. Science. 1995;270(5236):598–604. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narbonne GM. The Ediacara biota: Neoproterozoic origin of animals and their ecosystems. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2005;33:421–442. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laflamme M, Darroch SAF, Tweedt SM, Peterson KJ, Erwin DH. The end of the Ediacara biota: Extinction, biotic replacement, or Cheshire Cat? Gondwana Res. 2013;23(2):558–573. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amthor JE, et al. Extinction of Cloudina and Namacalathus at the Precambrian-Cambrian boundary in Oman. Geology. 2003;31(5):431–434. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li GX, et al. Early Cambrian metazoan fossil record of South China: Generic diversity and radiation patterns. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclim Palaeocl. 2007;254(1-2):229–249. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhuravlev AY, Riding R. The Ecology of the Cambrian Radiation. Columbia Univ Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maloof AC, et al. The earliest Cambrian record of animals and ocean geochemical change. Geol Soc Am Bull. 2010;122(11-12):1731–1774. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peng S, Babcock L, Cooper R. In: The Geologic Time Scale. Gradstein FM, Ogg JG, Schmitz MD, Ogg GM, editors. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2012. pp. 437–488. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luchinina VA, Korovnikov IV, Novozhilova NV, Tokarev DA. Benthic Cambrian biofacies of the Siberian Platform (hyoliths, small shelly fossils, archeocyaths, trilobites and calcareous algae) Stratigr Geol Correl. 2013;21(2):131–149. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuravlev AY, Wood RA. Anoxia as the cause of the mid-early Cambrian (Botomian) extinction event. Geology. 1996;24(4):311–314. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flügel E, Kiessling W. 2002. Phanerozoic Reef Patterns, eds Kiessling W, Flügel E, Golonka J SEPM Special Publication 72 (Soc Sediment Geol, Tulsa), pp 691–733.

- 35.Rowland SM. 2002. Phanerozoic Reef Patterns, eds Kiessling W, Flügel E, Golonka J SEPM Special Publication 72 (Soc Sediment Geol, Tulsa), pp 95–128.

- 36.Trotter JA, Williams IS, Barnes CR, Lécuyer C, Nicoll RS. Did cooling oceans trigger Ordovician biodiversification? Evidence from conodont thermometry. Science. 2008;321(5888):550–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1155814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saltzman MR, et al. Pulse of atmospheric oxygen during the late Cambrian. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(10):3876–3881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011836108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whittaker RH. Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon. 1972;21(2-3):213–251. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Araújo MS, Bolnick DI, Layman CA. The ecological causes of individual specialisation. Ecol Lett. 2011;14(9):948–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bengtson S, Zhao Y. Predatorial borings in late precambrian mineralized exoskeletons. Science. 1992;257(5068):367–369. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5068.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hua H, Pratt BR, Zhang LY. Borings in Cloudina shells: Complex predator-prey dynamics in the terminal Neoproterozoic. Palaios. 2003;18(4-5):454–459. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris SC, Peel JS. The earliest annelids: Lower Cambrian polychaetes from the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte, Peary Land, North Greenland. Acta Palaeontol Pol. 2008;53(1):137–148. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vannier J, Steiner M, Renvoisé E, Hu SX, Casanova JP. Early Cambrian origin of modern food webs: Evidence from predator arrow worms. Proc Biol Sci. 2007;274(1610):627–633. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao FC, Zhu MY, Hu SX. Community structure and composition of the Cambrian Chengjiang biota. Sci China Earth Sci. 2010;53(12):1784–1799. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao FC, et al. Diversity and species abundance patterns of the early Cambrian (Series 2, Stage 3) Chengjiang Biota from China. Paleobiology. 2014;40(1):50–69. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood R, Zhuravlev AY. Escalation and ecological selectively of mineralogy in the Cambrian Radiation of skeletons. Earth Sci Rev. 2012;115(4):249–261. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vermeij GJ. The origin of skeletons. Palaios. 1989;4(6):585–589. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao F, Bottjer DJ, Hu S, Yin Z, Zhu M. Complexity and diversity of eyes in early Cambrian ecosystems. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2751. doi: 10.1038/srep02751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanley SM. Predation defeats competition on the seafloor. Paleobiology. 2008;34(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhuravlev AY, Naimark EB. Alpha, beta, or gamma: Numerical view on the Early Cambrian world. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclim Palaeocl. 2005;220(1-2):207–225. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hortal J, Roura-Pascual N, Sanders NJ, Rahbek C. Understanding (insect) species distributions across spatial scales. Ecography. 2010;33(1):51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCartney MA, Keller G, Lessios HA. Dispersal barriers in tropical oceans and speciation in Atlantic and eastern Pacific sea urchins of the genus Echinometra. Mol Ecol. 2000;9(9):1391–1400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dalziel IWD. Neoproterozoic-Paleozoic geography and tectonics: Review, hypothesis, environmental speculation. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1997;109(1):16–42. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scotese CR. Late Proterozoic plate tectonics and palaeogeography: A tale of two supercontinents, Rodinia and Pannotia. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ. 2009;326:67–83. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torsvik TH, Rehnström EF. Cambrian palaeomagnetic data from Baltica: Implications for true polar wander and Cambrian palaeogeography. J Geol Soc London. 2001;158:321–329. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shields-Zhou G, Och L. The case for a Neoproterozoic oxygenation event: Geochemical evidence and biological consequences. GSA Today. 2011;21(3):4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Servais T, Harper DA, Munnecke A, Owen AW, Sheehan PM. Understanding the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE): Influences of paleogeography, paleoclimate, or paleoecology. GSA Today. 2009;19(4):4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valentine JW, Moores EM. Global tectonics and the fossil record. J Geol. 1972;80(2):167–184. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alroy J, et al. Phanerozoic trends in the global diversity of marine invertebrates. Science. 2008;321(5885):97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1156963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Darroch SAF, Laflamme M, Clapham ME. Population structure of the oldest known macroscopic communities from Mistaken Point, Newfoundland. Paleobiology. 2013;39(4):591–608. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peterson KJ. Macroevolutionary interplay between planktic larvae and benthic predators. Geology. 2005;33(12):929–932. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jablonski D, Lutz RA. Larval ecology of marine benthic invertebrates: Paleobiological implications. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 1983;58(1):21–89. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Narbonne G, et al. In: The Geologic Time Scale. Gradstein FM, Ogg JG, Schmitz MD, Ogg GM, editors. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2012. pp. 413–435. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scotese CR. 2001 Paleomap Project. Available at www.scotese.com. Accessed July 17, 2001.

- 65.Raup DM. Species diversity in the Phanerozoic: An interpretation. Paleobiology. 1976;2(4):289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alroy J. The shifting balance of diversity among major marine animal groups. Science. 2010;329(5996):1191–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.1189910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alroy J, et al. Effects of sampling standardization on estimates of Phanerozoic marine diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(11):6261–6266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111144698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shannon CE. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J. 1948;27:379–423, 623–656. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bray JR, Curtis JT. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol Monogr. 1957;27(4):325–349. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Foote M. Origination and extinction components of taxonomic diversity: General problems. Paleobiology. 2000;26(4):74–102. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Foote M. Pulsed origination and extinction in the marine realm. Paleobiology. 2005;31(1):6–20. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.