Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal and lineage choice are subject to intrinsic control. However, this intrinsic regulation is also impacted by external cues provided by niche cells. There are multiple cellular components that participate in HSC support with the mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) playing a pivotal role. We had previously identified a role for SH2 domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase-1 (SHIP1) in HSC niche function through analysis of mice with germline or induced SHIP1 deficiency. In this study, we show that the HSC compartment expands significantly when aged in a niche that contains SHIP1-deficient MSC; however, this expanded HSC compartment exhibits a strong bias toward myeloid differentiation. In addition, we show that SHIP1 prevents chronic G-CSF production by the aging MSC compartment. These findings demonstrate that intracellular signaling by SHIP1 in MSC is critical for the control of HSC output and lineage commitment during aging.

These studies increase our understanding of how myeloid bias occurs in aging and thus could have implications for the development of myeloproliferative disease in aging.

Introduction

The unique organization of the bone marrow (BM) provides an ideal setting for blood cell production. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) maintain blood cells throughout life by preserving quiescence, and thus longevity of the HSC compartment [1–3]. However, as mammals age, there is a decline in normal HSC function with impairment of self-renewal, survival, and differentiation [4,5]. The reasons for this decline in HSC output during aging are still being defined; however, HSC extrinsic and intrinsic genetic defects are both believed to contribute [6–8]. Changes in the cellular composition of the HSC niche during aging are also proposed to occur and can contribute to hematologic decline. However, documentation of these changes and their impact on the HSC compartment remain elusive.

The SH2 domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase-1 (SHIP1) removes the 5′ phosphate from the phosphatidyl inositol 3′ kinase (PI3K) product, PI(3,4,5)P3, enabling SHIP1 to oppose the PI3K activity and thereby regulate a variety of cellular signaling pathways important for proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and migration. As a key regulator of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, SHIP1 has the potential to modulate multiple signaling pathways downstream of receptors that impact HSC biology [9,10] and thus can influence HSC function, and homeostasis. Consistent with this, we and others have found that HSC isolated from germline SHIP1−/− mice demonstrate defective repopulation and self-renewal capacity [11,12]. In addition, germline SHIP1−/− mice exhibit increased production of niche-derived factors (G-CSF, TPO, MMP-9) that promote cycling and mobilization of HSC, but reduced production of the chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12 that lures HSC to sites in the BM that promote their quiescence [13]. Consistent with altered niche function in SHIP1−/− mice, SHIP1 was shown to be expressed by BM stromal cells which contain MSCs [13]. In addition, when SHIP1 deficiency was induced in HSC while they were resident in a SHIP1-competent niche, these SHIP1-deficient HSC were found to have normal long-term multilineage repopulation and self-renewal capacity [13], demonstrating that SHIP1 is not required in a cell-autonomous manner for HSC function. Liang et al. confirmed and extended these finding by showing that in a BM microenvironment that is globally SHIP1-deficient wild type (WT) HSC have defective lineage output [14]. These studies raised the possibility that SHIP1 expression by MSC is required for niche support of HSC quiescence and function.

To determine if SHIP1 specifically plays a role in MSC support of HSC function, we developed mice harboring a floxed SHIP1 locus [15] combined with a Cre recombinase transgene under the control of the Osterix promoter [16]. We refer to these as OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice [17]. We demonstrated that SHIP1 is selectively deleted in MSC of OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice [17]. Others, including Chen et al. and Mizoguchi et al., have also recently shown that the Osterix promoter enables Cre-mediated deletion or GFP transgene expression in MSC [18,19]. Age-associated decline in HSC function is thought to be influenced by extrinsic cues from the microenvironment that they reside in [20,21], and thus, we compared homeostasis, global repopulation, and lineage output of HSC from young and old OSXCreSHIPflox/flox versus age-matched SHIPflox/flox controls to determine if SHIP1 deficiency in the MSC compartment alters HSC behavior during aging.

Materials and Methods

Mice and genotyping

SHIPflox/flox mice [15] were bred with Osterix Cre [16] transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory) to generate OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice, where SHIP1 is deleted in MSC [17]. SHIPflox/flox mice were used as controls. Genotyping of Cre transgenic mice was performed by PCR using primers detecting the Cre sequence (P1, 5′-GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT-3′; P2, 5′-GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTA-3′). PCR was performed using REDtaq ReadyMix (Sigma) with a five-step PCR protocol as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of each of the following: denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, primer annealing at 51°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 2 min. C57BL/6 SJL (CD45.1, WT) for BM transplant experiments were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Genotyping of SHIPflox and SHIPwt mice was performed by PCR using primers detecting the lox-P sequence (P1, 5′-TTG AAC ACC TCT GCC AAC TGC GTC 3′; P2 5′-CCA CAA GTG ATG CTA AGA GAT GC 3′). PCR was performed using REDtaq with a five-step PCR protocol as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min; 35 cycles of each of the following: denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, primer annealing at 55°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 6 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The SUNY Upstate Medical University Committee for Humane Use of Animals approved all animal experiments.

Hematologic analysis

Peripheral blood (PB) samples were collected by submandibular bleeding and placed in EDTA-coated microtubes (Sarstedt Co.). Absolute blood cell number was analyzed using the mouse species program in HEMAVET 950S Veterinary Hematology Analyzer (Drew Scientific, Inc.).

Flow cytometry analysis

Whole BM (WBM) cells were treated with CD16/CD32 mouse Fc block (2.4G2) on ice for 15 min before antibody staining. For multilineage analysis, PB-mononuclear cells (PBMC) or WBM cells were stained with CD3ɛ-FITC (145-2C11), CD19-PerCP-Cy5.5 (1D3), Mac1-PE (M1/70), Gr1-PE (RB6-8C5), and Gr1-Alexa700 (RB6-8C5). The Lin−cKit+Sca1+CD34−Flk2− (LSKF34-) phenotype was utilized to determine the frequency of LSK, long-term HSC (LT-HSC), short-term HSC (ST-HSC), and multipotent progenitors (MPP); the stain comprised Lineage panel PerCP-Cy5.5 (145-2C11, RB6-8C5, TER-119, RA3-6B2, M1/70), cKit-APC (2B8), Sca1-PeCy7 (D7), CD34-FITC (RAM34), Flk2-PE (A2F10). For global reconstitution, PBMC were stained with CD45.1-PeCy7 (A20) and CD45.2-APC (104). Cells were washed twice with staining media (2% heat-inactivated FBS in PBS) and resuspended in staining media and DAPI for dead cell exclusion. For natural killer (NK) cell analysis, splenocytes were harvested. Red blood cells were lysed using the ACK lysis buffer from eBioscience. Fc receptors were blocked with an anti-CD16/CD32 (2.4G2) antibody (BD Biosciences). Invitrogen fixable aqua live/dead stain was used according to the manufacturer's instructions for dead cell exclusion. Surface markers were then stained using NK1.1 (PK136), CD3ɛ (145-2C11), CD244.2 (2B4), Ly49D (4E5), and Ly49H (3D10). The samples were analyzed on a flow cytometer LSRII or Fortessa (BD Biosciences). All antibodies were from BD Biosciences or eBioscience. All fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) data were analyzed using FlowJo (9.4.3) software.

Serum cytokine analysis

G-CSF (catalogue No. MCS00), M-CSF (catalogue No. MMC00), SDF-1 (catalogue No. MCX120), and MMP-9 (catalogue No. MMPT90) levels in mouse serum were measured using ELISA kits (R&D Systems).

Cell cycle analysis

WBM cells were stained for LSK34 (as described above), followed by fixation (BD Cytofix/Cytoperm) and staining for Ki67-FITC (BD Biosciences) and DAPI. Analysis was performed on a flow cytometer Fortessa (BD Biosciences) and data analysis was conducted using FlowJo (9.4.3) software.

BM cell transplantation studies

For primary BM transplant, 8–12-week-old CD45.1 (WT) hosts were lethally irradiated at 1,100 Rads (Split dose: 550 Rads given 4 h apart). For WBM competition, 1×106 WBM cells from OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (CD45.2) or SHIPflox/flox (CD45.2) mice were combined with 1×106 WBM cells from CD45.1 (WT) mice and injected into the retro-orbital vein of CD45.1 hosts. PBMC from hosts were collected monthly for a 4-month period to determine global and multilineage repopulation. After the 4-month analysis, host CD45.1 mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and WBM was collected and serially transplanted into CD45.1 hosts to examine the self-renewal capacity. PBMC from serial transplanted mice were analyzed 1 month post-transplant to determine global and multilineage reconstitution.

Western blot analysis

Sorted cells were lysed and equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with specific antibodies against SHIP1 (P1C1) and Actin (I-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-mouse or anti-goat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), as per the manufacturer's recommendations. Proteins were detected using the Super Signal ECL Substrate (Pierce) on ChemiDoc XRS+(BioRad) with Image Lab 4.0 Software.

Cell sorting

Splenocytes from secondary transplant mice were treated with CD16/CD32 mouse Fc block (2.4G2) on ice for 15 min before antibody staining. Splenocytes were stained with CD45.1-PeCy7 (A20) and CD45.2-APC (104). Dead cells were excluded by DAPI staining and were sorted with a FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). Viable sorted cells were used for western blot analysis.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software Prism 5.0 (GraphPad).

Results

SHIP1 expression by the MSC compartment is required for maintenance of HSC homeostasis in aged mice

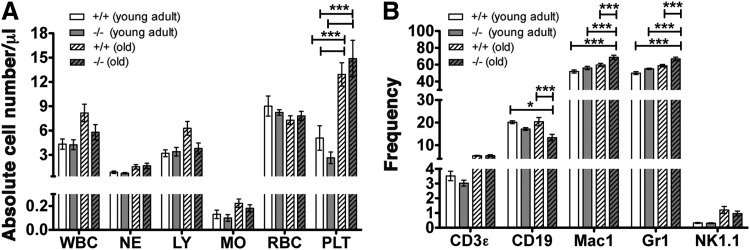

To analyze the impact of a SHIP1-deficient MSC compartment on HSC function, we initially compared both PB and BM of young adult (8–14 weeks) and old (18–24 months) OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice versus age-matched SHIPflox/flox controls. We observed a significantly higher frequency of platelets in the PB of aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox control mice (18–24 months) in comparison to young cohorts (Fig. 1A). We observed reduced B-cell frequency in the BM compartment of old OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice (Fig. 1B), but not in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd). Interestingly, we observed higher myeloid (Mac1+) and granulocytic (Gr1+) frequencies in the BM compartment (Fig. 1B), but not in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. S1) of aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice in comparison to age-matched SHIPflox/flox controls. In addition, we found equal frequency of NK cells from young adult and old OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice and SHIPflox/flox age-matched controls in both the BM and spleen (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S1). Surprisingly, however, we noted significantly decreased populations of NK cells that express the activating receptors Ly49D and Ly49H in aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice compared to age-matched SHIPflox/flox controls (Supplementary Fig. S2A) (no difference was observed in young adult cohorts). We also observed significantly increased expression of the SLAM family receptor 2B4 by OSXCreSHIPflox/flox NK cells compared to SHIPflox/flox NK cells (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Reduced Ly49H and D expression and an increased 2B4 expression were previously observed in NK cells of mice with germline SHIP1 deficiency [22,23]. These changes partially recapitulate the NK cell repertoire defects reported in germline SHIP1−/− mice and indicate a lineage extrinsic role for SHIP1 in the regulation of at least some aspects of the NK cell receptor repertoire.

FIG. 1.

SHIP1 in the MSC compartment is required for normal hematolymphoid output by HSC in aged mice. (A) Absolute blood cell numbers were analyzed using an automated blood cell analyzer, WBC, white blood cells (×103); NE, neutrophils (×103); LY, lymphocytes (×103); MO, monocytes (×103); RBC, red blood cells (×106); PLT, platelets (×105). (B) Frequency of hematolymphoid lineages, lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, and NK cells), and myeloid cells (Mac-1, Gr-1) in the BM of young adult and old OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox mice [two-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparisons was performed (n≥5)]. HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; NK, natural killer; SHIP1, SH2 domain-containing inositol 5′-phosphatase-1.

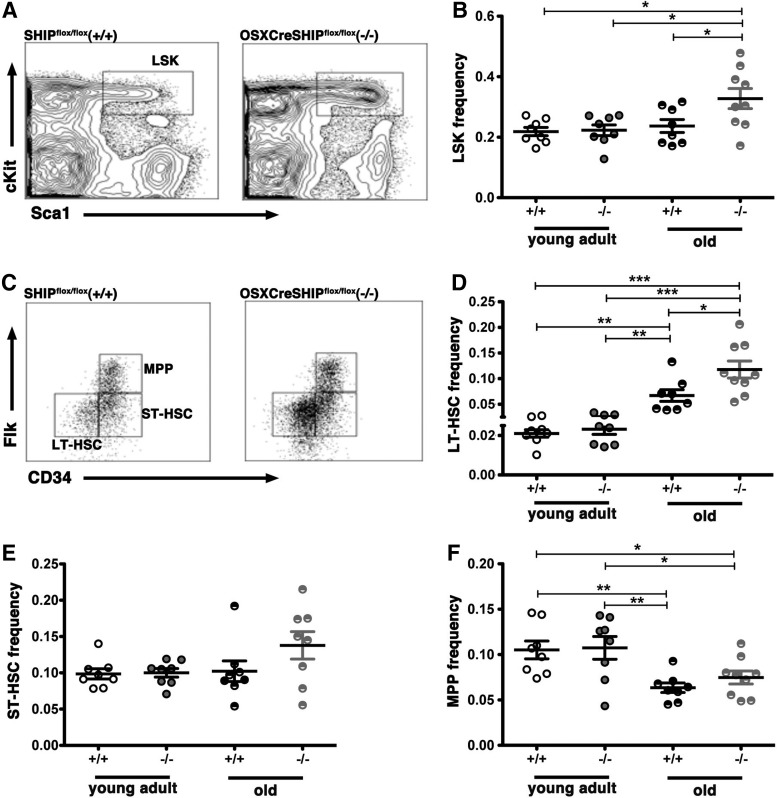

Analysis of the BM hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HS/PC) compartment showed no difference in the frequency of the broadly defined HS/PC pool as demarcated by the LSK phenotype (Lin−Sca1+cKit+) [24,25] in young adult OSXCreSHIPflox/flox versus age-matched SHIPflox/flox controls. However, in aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice, the LSK frequency was significantly increased relative to aged SHIPflox/flox, young OSXCreSHIPflox/flox, or young SHIPflox/flox mice (Fig. 2A, B). This increase in the HS/PC pool appears to be largely confined to the LT-HSC (CD34−Flk2−Lin−Sca-1+cKit+) subset [26–28] as LT-HSC are significantly increased in aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice versus age-matched SHIPflox/flox, young OSXCreSHIPflox/flox, or young SHIPflox/flox mice (Fig. 2D), but no significant difference was observed in the frequency of more committed progenitors within the LSK stem/progenitor pool, including ST-HSC and MPP [28,29], in either young adult or age-matched OSXCreSHIPflox/flox versus SHIPflox/flox controls (Fig. 2E, F). However, consistent with aging, we did observe a decrease in MPP population [6] in both age-matched OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox controls (Fig. 2E, F). We observed no difference in total BM cellularity in young adult versus aged cohorts of OSXCreSHIPflox/flox or with respect to age-matched SHIPflox/flox controls (Supplementary Fig. S3).

FIG. 2.

SHIP1 in the MSC compartment is required for maintenance of the HSC numbers in aged mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry analysis of Lin−Sca-1+cKit+ (LSK) in the WBM of SHIPflox/flox (+/+) and OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) hosts. (B) Frequency of LSK cells of young adult and old SHIPflox/flox (+/+) and OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) hosts. (C) Representative flow cytometry plots of LT-HSC (LSKFlk2−CD34−), ST-HSC (LSKFlk2−CD34+), and MPP (LSKFlk2+CD34+) populations in the WBM of SHIPflox/flox (+/+) and OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) mice. (D) Frequency of LT-HSC. (E) Frequency of ST-HSC. (F) Frequency of MPP population (for young adult cohorts, n=8, and old cohorts, n≥8/group,±SEM. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.001, and ***P≤0.0001, Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test). LT-HSC, long-term HSC; MPP, multipotent progenitors; ST-HSC, short-term HSC; WBM, whole bone marrow.

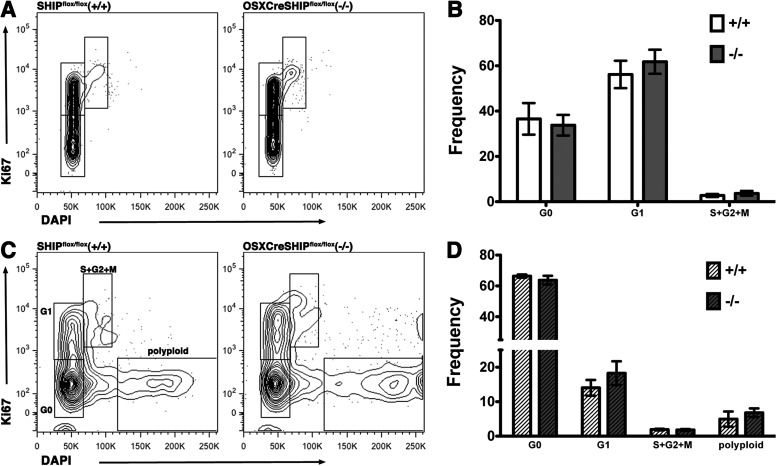

We further investigated the age-associated expansion of LT-HSC population in OSXCreSHIPflox/flox by performing cell cycle analysis on LT-HSC population. No difference was observed in the young adult cell cycle status (Fig. 3A, B). We found no increase in cycling or change in the cell cycle status of aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox in comparison to age-matched control SHIPflox/flox mice (Fig. 3C, D). Interestingly, we did observe a distinct Ki67−DAPIhi population in both aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox mice and at a comparable frequency in both genotypes (Fig. 3C, D). This population of LT-HSC has a much higher DNA content than 2N diploid cells (∼4N), indicating that they are polyploid. Intriguingly, this Ki67−DAPIhi polyploid LT-HSC population is not detected in LT-HSC of any young adult mice we analyzed of either genotype (Fig. 3A, B). The age-related appearance of this polyploid LT-HSC population suggests that aging induces genome instability and polyploidy in a subset of the LT-HSC compartment. Polyploidy is known to lead to cell senescence in other tissues [30] and thus it is tempting to speculate that this Ki67−DAPIhi population of LT-HSC reflects senescent or defective HSC in aged mice.

FIG. 3.

Cell cycle analysis in OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox mice. Cell cycle distribution was analyzed by Ki67 and DAPI staining of old and young adult OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice (−/−) versus SHIPflox/flox controls (+/+) LT-HSC (LSKCD34−). (A) Representative flow plots of young adult cohort and (B) bar graph depicting the percentage distribution of LT-HSC (LSKCD34−) in G0, G1, and S+G2/M stages of the cell cycle of young adult SHIPflox/flox (+/+) and OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) mice. (C) Representative flow plots of old cohort and (D) bar graph depicting the percentage distribution of LT-HSC (LSKCD34-) in G0, G1, and S+G2/M stages of the cell cycle and Ki67-DAPIhi polyploidy (“polyploid”) LT-HSC (n≥5/group) of old SHIPflox/flox (+/+) and OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) mice.

Analysis of key niche factors showed that G-CSF production is selectively increased in aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice compared to all other cohorts (age-matched SHIPflox/flox, young adult OSXCreSHIPflox/flox, or young adult SHIPflox/flox mice) (Fig. 4A). No significant changes in SDF-1, MMP-9, or M-CSF production in aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice versus the other three groups were observed (Fig. 4B–D). The increased and chronic production of G-CSF would be anticipated to promote the in vivo expansion of LT-HSC that we observe in aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice, as G-CSF selectively promotes primitive HSC expansion after myeloablation [31] as well as cycling of dormant HSC during normal physiology [32]. However, we observed no difference in the cycling status of LT-HSC of the aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox versus SHIPflox/flox controls.

FIG. 4.

Cytokine analysis in OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox mice. Serum (A) G-CSF, (B) SDF-1, (C) MMP-9, and (D) M-CSF levels in young adult and old OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox mice (n≥5/group,±SEM. *P≤0.05 and ***P≤0.0001, Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test).

A SHIP1-deficient MSC BM microenvironment skews HSC toward a myeloid fate with aging

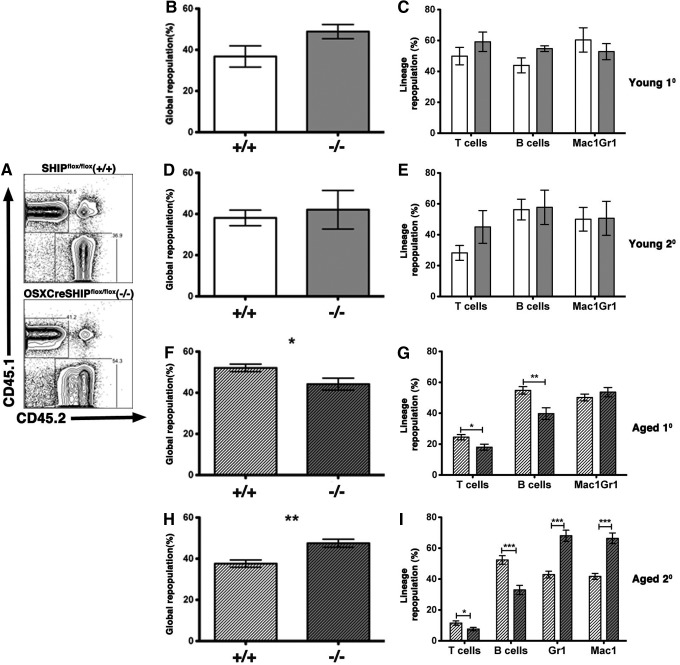

To further address the role of SHIP1 in an aging MSC compartment and their support of normal HSC function, we analyzed HSC from young and aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox BM donors for their capacity to mediate global blood cell repopulation, long-term multilineage repopulation, and self-renewal as compared to age-matched SHIPflox/flox controls. To accomplish this, C57BL6/CD45.1 mice were lethally irradiated and cotransplanted with equal numbers of WT (CD45.1) BM cells and OSXCreSHIPflox/flox or SHIPflox/flox BM (CD45.2). HSC derived from both young OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox BM donors yielded equivalent global and multilineage repopulation in this competition assay (Fig. 5A–C). To measure HSC self-renewal potential we performed serial transfers of primary BM into secondary lethally irradiated WT (CD45.1) hosts and analyzed their ability to perform both global and multilineage repopulation after serial transfer—measures of HSC self-renewal. Again, no differences were observed in the global or multilineage repopulation capacity after serial transplantation when HSC were derived from young OSXCreSHIPflox/flox versus age-matched SHIPflox/flox BM donors (Fig. 5D, E).

FIG. 5.

Aged HSCs within the SHIP1-deficient MSC BM microenvironment exhibit skewed differentiation toward the myeloid lineage. Primary and secondary transplants were established, where equal numbers of WBM cells from young adult and old SHIPflox/flox (+/+) or OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) donors, and competed against CD45.1 (WT) BM cells in lethally irradiated CD45.1 (WT) hosts. (A) Representative flow cytometry analysis of CD45.1 (WT) and CD45.2 [SHIPflox/flox (+/+) or OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−)] in the PBMC. For young adult primary transplant, (B) global and (C) multilineage repopulation: T lymphocytes (CD3ɛ+), B cells (CD19+), and myeloid cells (Mac1+,Gr1+) in primary transplant hosts reconstituted with young adult SHIPflox/flox (+/+) or OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) BM HSC (4 months post-transplant). Analysis of (D) global and (E) multilineage repopulation in secondary transplant hosts reconstituted with BM from primary hosts reconstituted with young adult SHIPflox/flox (+/+) or OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) BM HSC (1 month post-transplant) (n=2, n=4). Analysis of (F) global and (G) multilineage repopulation in primary transplant hosts reconstituted with BM from aged SHIPflox/flox (+/+) or OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) BM donors (4 months post-transplant) (n=3, n=4). Analysis of (H) global and (I) multilineage repopulation in secondary transplant hosts reconstituted with BM from primary hosts reconstituted with BM from aged SHIPflox/flox (+/+) or OSXCreSHIPflox/flox (−/−) donors (1 month post-transplant) (n=3, n=5,±SEM. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.001, and ***P≤0.0001, Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test). PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; WT, wild type.

We then analyzed HSC output of aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox BM donors in the same competition assays. In this study, there was a significant decrease in primary global repopulation efficacy of HSC derived from OSXCreSHIPflox/flox donors versus SHIPflox/flox controls (Fig. 5F). In addition, we also observed significantly diminished lymphoid output, but normal myeloid repopulation by HSC from aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox BM donors (Fig. 5G). Upon serial transfer of BM to secondary hosts, these differences became more profound as we found that HSC derived from aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice demonstrated significant increased global repopulation (Fig. 5H) indicating increased proliferative capacity by aged HSC clones derived from OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice. In addition, the myeloid output of these aged HSC was significantly increased relative to age-matched HSC from SHIPflox/flox hosts (Fig. 5I). As seen in the primary reconstituted animals, the lymphoid output of aged OSXCreSHIPflox/flox HSC remained significantly diminished upon serial transfer to secondary hosts when compared to age-matched SHIPflox/flox HSC (Fig. 5I). Thus, as they age, HSC derived from hosts with a SHIP1-deficient MSC compartment demonstrate increased contribution to global blood cell production after serial transfer and bias toward a myeloid differentiation fate. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that myeloid-biased HSC have a higher self-renewal capacity and reduced lymphoid repopulating efficacy [33–35].

To rule out the possibility that inappropriate deletion of SHIP1 in HSC derived from OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice might have caused an intrinsic effect on their function, we analyzed SHIP1 expression in OSXCreSHIPflox/flox and SHIPflox/flox splenocytes derived from serially transplanted hosts. We observed equivalent SHIP1 expression by hematolymphoid cells derived from OSXCreSHIPflox/flox HSC as compared to cells derived from SHIP1-competent SHIPflox/flox HSC (Supplementary Fig. S4). This analysis confirms that HSC derived from the original OSXCreSHIPflox/flox donors remained SHIP1 competent throughout both primary and serial transplantation.

Discussion

Our findings provide the first direct demonstration that SHIP1 expression in the MSC compartment plays a pivotal role in maintaining HSC homeostasis, sustaining their lymphoid output, and limiting myelopoiesis during mammalian aging. Future analysis of the cellular and molecular perturbations that occur in the SHIP1-deficient MSC compartment with age may provide insights into how these cells exert control over HSC function during aging. Whether SHIP1 prevents the emergence of a G-CSF producing MSC subset during aging or simply represses its induction in all MSC may prove informative. We hypothesize then that loss of SHIP1 in the MSC of OSXCreSHIPflox/flox mice leads to qualitative changes in these niche cells during aging (eg, increased G-CSF production) that may promote epigenetic modifications in HSC. These changes would then be inherited and manifest upon serial transfer of these HSC. Our findings further suggest that loss of SHIP1 expression or activity in the aging MSC compartment could contribute to the increased incidence of myeloproliferative syndromes, BM failure, and the development of myeloid malignancies in aging humans. If loss of, or significantly diminished, SHIP1 expression can be confirmed in such patients, perhaps therapeutic strategies to increase SHIP1 enzymatic activity merit exploration in myeloproliferative and BM failure syndromes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the NIH (RO1 HL72523, R01 HL085580, R01 HL107127) and the Paige Arnold Butterfly Run. The authors wish to thank B. Lesniak, C. Youngs, and B. Toms for genotyping of mice. W.G.K. is the Murphy Family Professor of Children's Oncology Research, an Empire Scholar of the State University of NY and a Senior Scholar of the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America.

Author Disclosure Statement

W.G.K., S.I., R.B., and M.G. have patents, pending and issued, concerning the analysis and targeting of SHIP1 in disease.

References

- 1.Li Z. and Li L. (2006). Understanding hematopoietic stem-cell microenvironments. Trends Biochem Sci 31:589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong Y. and Linheng L. (2006). The stem cell niches in bone. J Clin Invest 116:1195–1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li L. and Xie T. (2005). STEM cell niche: structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21:605–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers SM, Shaw CA, Gatza C, Fisk CJ, Donehower LA. and Goodell MA. (2007). Aging hematopoietic stem cells decline in function and exhibit epigenetic dysregulation. PLoS Biol 5:e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beerman I, Maloney WJ, Weissmann IL. and Rossi DJ. (2010). Stem cells and the aging hematopoietic system. Curr Opin Immunol 22:500–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi DJ, Bryder D, Zahn JM, Ahlenius H, Sonu R, Wagers AJ. and Weissman IL. (2005). Cell intrinsic alterations underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:9194–9199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolthuis CM, de Haan G. and Huls G. (2011). Aging of hematopoietic stem cells: intrinsic changes or micro-environmental effects?. Curr Opin Immunol 23:512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ergen AV. and Goodell MA. (2010). Mechanisms of hematopoietic stem cell aging. Exp Gerontol 45:286–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Damen JE, Ware M, Hughes M. and Krystal G. (1997). SHIP, a new player in cytokine-induced signalling. Leukemia 11:181–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim CH, Hangoc G, Cooper S, Helgason CD, Yew S, Humphries RK, Krystal G. and Broxmeyer HE. (1999). Altered responsiveness to chemokines due to targeted disruption of SHIP. J Clin Invest 104:1751–1759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helgason CD, Antonchuk J, Bodner C. and Humphries RK. (2003). Homeostasis and regeneration of the hematopoietic stem cell pool are altered in SHIP-deficient mice. Blood 102:3541–3547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desponts C, Hazen AL, Paraiso KH. and Kerr WG. (2006). SHIP deficiency enhances HSC proliferation and survival but compromises homing and repopulation. Blood 107:4338–4345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazen AL, Smith MJ, Desponts C, Winter O, Moser K. and Kerr WG. (2009). SHIP is required for a functional hematopoietic stem cell niche. Blood 113:2924–2933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang OD, Lu J, Nombela-Arrieta C, Zhong J, Zhao L, Pivarnik G, Mondal S, Chai L, Silberstein LE. and Luo HR. (2013). Deficiency of lipid phosphatase SHIP enables long-term reconstitution of hematopoietic inductive bone marrow microenvironment. Dev Cell 25:333–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang JW, Howson JM, Ghansah T, Desponts C, Ninos JM, May SL, Nguyen KH, Toyama-Sorimachi N. and Kerr WG. (2002). Influence of SHIP on the NK repertoire and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Science 295:2094–2097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodda SJ. and McMahon AP. (2006). Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development 133:3231–3244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyer S, Viernes D, Chisholm J, Margulies B. and Kerr WG. (2014). SHIP1 regulates MSC numbers and their osteolineage commitment by limiting induction of the PI3K/Akt/betacatenin/Id2 axis. Stem Cells Dev 23:2336–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Shi Y, Regan J, Karuppaiah K, Ornitz DM. and Long F. (2014). Osx-Cre targets multiple cell types besides osteoblast lineage in postnatal mice. PLoS One 9:e85161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizoguchi T, Pinho S, Ahmed J, Kunisaki Y, Hanoun M, Mendelson A, Ono N, Kronenberg HM. and Frenette PS. (2014). Osterix marks distinct waves of primitive and definitive stromal progenitors during bone marrow development. Dev Cell 29:340–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raveh-Amit H, Berzsenyi S, Vas V, Ye D. and Dinnyes A. (2013). Tissue resident stem cells: till death do us part. Biogerontology 14:573–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner W, Horn P, Bork S. and Ho AD. (2008). Aging of hematopoietic stem cells is regulated by the stem cell niche. Exp Gerontol 43:974–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahle JA, Paraiso KH, Costello AL, Goll EL, Sentman CL. and Kerr WG. (2006). Cutting edge: dominance by an MHC-independent inhibitory receptor compromises NK killing of complex targets. J Immunol 176:7165–7169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fortenbery NR, Paraiso KH, Taniguchi M, Brooks C, Ibrahim L. and Kerr WG. 2010. SHIP influences signals from CD48 and MHC class I ligands that regulate NK cell homeostasis, effector function, and repertoire formation. J Immunol 184:5065–5074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S. and Weissman IL. (1988). Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science 241:58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikuta K. and Weissman IL. (1992). Evidence that hematopoietic stem cells express mouse c-kit but do not depend on steel factor for their generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:1502–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison SJ. and Weissman IL. (1994). The long-term repopulating subset of hematopoietic stem cells is deterministic and isolatable by phenotype. Immunity 1:661–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H. and Nakauchi H. (1996). Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science 273:242–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen JL. and Weissman IL. (2001). Flk-2 is a marker in hematopoietic stem cell differentiation: a simple method to isolate long-term stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:14541–14546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adolfsson J, Borge OJ, Bryder D, Theilgaard-Monch K, Astrand-Grundstrom I, Sitnicka E, Sasaki Y. and Jacobsen SE. (2001). Upregulation of Flt3 expression within the bone marrow Lin(-)Sca1(+)c-kit(+) stem cell compartment is accompanied by loss of self-renewal capacity. Immunity 15:659–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davoli T. and de Lange T. (2011). The causes and consequences of polyploidy in normal development and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 27:585–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison SJ, Wright DE. and Weissman IL. (1997). Cyclophosphamide/granulocyte colony-stimulating factor induces hematopoietic stem cells to proliferate prior to mobilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:1908–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G, van der Wath RC, Blanco-Bose W, Jaworski M, Offner S, Dunant CF, Eshkind L, et al. (2008). Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell 135:1118–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller-Sieburg CE, Cho RH, Karlsson L, Huang JF. and Sieburg HB. (2004). Myeloid-biased hematopoietic stem cells have extensive self-renewal capacity but generate diminished lymphoid progeny with impaired IL-7 responsiveness. Blood 103:4111–4118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller-Sieburg CE, Cho RH, Thoman M, Adkins B. and Sieburg HB. (2002). Deterministic regulation of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Blood 100:1302–1309 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pang WW, Price EA, Sahoo D, Beerman I, Maloney WJ, Rossi DJ, Schrier SL. and Weissman IL. (2011). Human bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells are increased in frequency and myeloid-biased with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:20012–20017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.