ABSTRACT

Purpose: To identify professional behaviours measured in objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) by Canadian university physical therapy (PT) programs. Method: A cross-sectional telephone survey was conducted to review current practice and determine which OSCE items Canadian PT programs are using to measure PT students' professional behaviours. Telephone interviews using semi-structured questions were conducted with individual instructors responsible for courses that included an OSCE as part of the assessment component. Results: Nine PT programmes agreed to take part in the study, and all reported conducting at least one OSCE. The number and characteristics of OSCEs varied both within and across programs. Participants identified 31 professional behaviour items for use in an OSCE; these items clustered into four categories: communication (n=14), respect (n=10), patient safety (n=4), and physical therapists' characteristics (n=3). Conclusions: All Canadian entry-level PT programmes surveyed assess professional behaviours in OSCE-type examinations; however, the content and style of assessment is variable. The local environment should be considered when determining what professional behaviours are appropriate to assess in the OSCE context in individual programmes.

Key Words: education, professional, educational measurement, students

RÉSUMÉ

Objet : Cerner les comportements professionnels mesurés dans les examens cliniques objectifs structurés dans le cadre des programmes de physiothérapie des universités canadiennes. Méthode : Un sondage téléphonique transversal a été effectué pour examiner la pratique actuelle et déterminer les éléments des examens cliniques objectifs structurés (ECOS) utilisés dans le cadre des programmes canadiens de physiothérapie pour mesurer les comportements professionnels des étudiants en physiothérapie. On a mené des entrevues téléphoniques dans lesquelles on posait des questions semi-structurées aux instructeurs chargés des cours comportant un ECOS dans la composante d'évaluation. Résultats : Neuf programmes de physiothérapie ont accepté de participer à l'étude, et les répondants ont tous déclaré qu'ils effectuaient au moins un examen clinique objectif structuré. Le nombre et les caractéristiques des ECOS variaient à la fois au sein d'un même programme et entre les programmes. Les participants ont cerné 31 éléments de comportement professionnel à mesurer dans un ECOS; ils se regroupent en quatre catégories: communication (n=14), respect (n=10), sécurité des patients (n=4) et caractéristiques des physiothérapeutes (n=3). Conclusions : Tous les programmes de physiothérapie sondés au niveau débutant évaluent les comportements professionnels à l'aide d'examens de type ECOS; toutefois, le contenu et le style de l'examen sont variables. Il faut tenir compte de l'environnement local lorsqu'on détermine les comportements professionnels qu'il faut évaluer dans le contexte de l'ECOS dans les programmes individuels.

Mots clés : éducation, étudiants, mesure de l'éducation, physiothérapie, professionnel

Professional behaviour in health care has been defined in many ways and encompasses attributes including altruism, reliability and responsibility, honesty and integrity, respect, and communication and interpersonal skills.1 In the Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada, professional is defined as “committed to the best interests of clients and society through ethical practice, support of profession-led regulation, and high personal standards of behaviour.”2(p.14) This broad and complex construct presents challenges to educators responsible for teaching and assessing competencies related to professional behaviour. As with many skills in physical therapy (PT), larger, complex tasks are broken down into more measurable discrete items during teaching and subsequent assessment. May and colleagues3 developed a model to measure the professional attributes of PT students; following a consensus process, 10 professional attributes called generic abilities emerged: commitment to learning, interpersonal skills, communication skills, effective use of time and resources, use of constructive feedback, problem solving, professionalism, responsibility, critical thinking, and stress management.3 Jette and Portney4 tested the construct validity of this model and found that 7 of these attributes accounted for the majority of the variance between students at different levels of clinical education. When asked to rank the importance of the 10 professional attributes of the generic abilities, students and clinicians found common ground on half the items, agreeing on the rank order (from most to least important) of the professional attributes of responsibility, professionalism, communication skills, interpersonal skills, and problem solving.5

Bossers and colleagues6 attempted to define and develop professionalism in an occupational therapy program. They outlined three broad categories of qualities that make up professionalism, each containing further subcategories: (1) professional parameters (legal issues, ethics, morality), (2) professional behaviours (skills and practice, relationships, presentation) and (3) professional responsibility (profession, self, community, employer–client).6 The models of both May and colleagues3 and Bossers and colleagues6 are examples of a professional program's attempt to define the component parts or items of the larger complex concept of professional behaviour.

Evidence of the importance of professionalism is supported by the results of a study from the United States in which 98% of the PT educators surveyed identified professionalism as an important component of the PT curriculum.7 Davis described a more robust investigation of the teaching of professionalism with less examination of assessment.7 In this study, the only assessment of professionalism reported was the frequency of negative student behaviour related to professionalism.7

Professional behaviours, as with any other set of skills that health professional students learn, are taught as part of the curriculum and may be subject to assessment. Student assessment can serve many purposes. In addition to determining students' level of knowledge or skill, assessment can motivate them to learn what is important.8 Early work related to health care student assessment primarily came from medical education. Historically, assessment of medical students has been related to their knowledge and skill competencies;9,10 formal teaching of professionalism was not typically part of medical education 30 years ago,1 and assessment of professionalism is an even more recent endeavour.9 Van Mook and colleagues10 identified five different approaches to assessing professional behaviours: peer and self-assessment, objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), direct faculty observation, critical incident reports, and learner-maintained portfolios. They10 advocated using a combination of these methods, rather than one assessment alone, to get a truer picture of students' abilities.

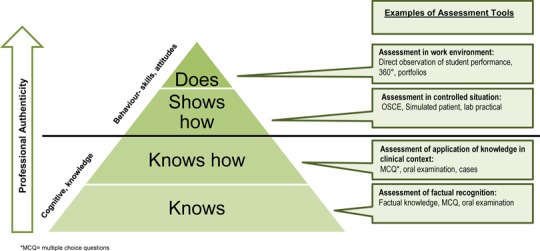

The type of competency assessment should align with what the student is learning (knowledge, skills, or behaviours). Miller11 has proposed a framework for assessing competence in clinical skills in which degrees of competence are displayed in four stages: “knows,” “knows how,” “shows how,” and “does”; knows and knows how assess cognitive elements, whereas shows how and does assess behaviours (see Figure 1). As assessments progress through these levels, their context authenticity increases.9 The OSCE fits into the third stage, shows how, and assessment of students during a clinical experience fits into the highest level, does.

Figure 1.

Miller's pyramid: framework for assessing clinical competence.

Adapted from Miller.11

*MCQ=multiple-choice questions.

The type of assessment should also reflect the type of learning and the type of competency of the student. The OSCE is a timed multi-station examination that uses trained or standardized patients to simulate clinical scenarios. It was originally developed to evaluate clinical competencies not adequately assessed by written examinations or in clinical environments.12,13 In medical education, the OSCE is recognized as a valid and reliable method of objectively evaluating students' clinical competence in various domains.12–14 Used by academic programs, often before clinical internships, it provides more assurance that students are prepared for the clinical environment, in which the stakes are higher.

The OSCE assesses whether the student is competent in Miller's11 third phase (shows how) before he or she is expected to do. Several studies in medical education have looked at the role of the OSCE in assessing professional behaviours, including communication,15 respect,16,17 and empathy,18 and we found five published literature reviews relating to the general assessment of professionalism in medical students,1,19–22 which highlighted the challenges of assessing professional behaviours and reinforced the notion that many individual characteristics make up the larger concept of professional behaviour.

In reviewing how our PT program assessed professional behaviour in the context of an OSCE, we recognized that the evidence in the PT literature was not sufficient to guide decisions. Because we could not find any studies that looked at assessment of PT students' professional behaviour skills in the academic environment before their clinical experience, we undertook a study to determine whether other Canadian PT programs were assessing professional behaviour in their OSCEs.

The purpose of this study was to identify the professional behaviours measured in OSCEs by university PT programs in Canada. The results of this review of current practice will inform a future study examining our local OSCE examiners' perceptions of the importance and feasibility of assessing these behaviours in the context of an OSCE.

Methods

After obtaining approval from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board in May 2011, we conducted a cross-sectional telephone survey23 to determine the items that English-speaking Canadian Master of Science in Physical Therapy (MScPT) or equivalent programmes were using in OSCEs to measure students' professional behaviours. Telephone interviews using semi-structured questions took place from June through December 2011.

Questionnaire development

The measurement tool for the study was a 21-item interview questionnaire consisting primarily of open-ended questions. We developed the questionnaire using relevant research pertaining to OSCEs, other surveys that explored the same concepts, and input from key informants, including educational experts and experienced OSCE examiners. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: introduction, demographic information (three questions), information about OSCEs specific to an individual course (nine questions), and information about OSCEs specific to professional behaviours (nine questions).

The introduction section informed participants of the nature of the study and its relevance to them; the demographic information section collected data on participants' university program, their content area (e.g., acute care, geriatrics, community), the year (1 or 2) in which they taught, and their area of practice (cardiorespiratory, neurosciences, musculoskeletal, other).

The third section elicited information about the general structure of the OSCE, including number of stations, length of time at each station, type of examiner used, and assessment methods or rating scales.

The final section asked questions specific to the professional behaviours assessed during the OSCE, including specific elements of professional behaviours, criteria, and grading components. Finally, an open-ended question invited participants to add further detail to their responses. Before the interviews began, physical therapists with experience in the design and execution of OSCEs reviewed the interview questions to inform modifications to the interview guide and enhance clarity, organization, and face validity.

Participants and recruitment

The target population for our study consisted of individual PT instructors responsible for courses with an OSCE component in the context of a 2-year MScPT (or equivalent) program at any English-medium Canadian university between 2011 and 2012.

To recruit potential participants, we sent an email invitation to the chairs of PT departments (or equivalents) at eligible Canadian universities to inform them of the project and request administrative consent.

We used purposive sampling to identify representatives from each area of practice: musculoskeletal, cardiorespiratory, neurosciences, and other. Snowball sampling also generated names of other PT faculty involved in OSCEs at their university. We contacted suggested participants by telephone and email, using a modified Dillman24 three-step approach that included initial mailing of information to those who were identified; a follow-up email, telephone call, or both to establish a convenient interview time; and a follow-up thank-you email after the interview. Consent was obtained before the interviews.

Data collection

Thirty-minute interviews were conducted by one of the three physical therapist investigators–authors. During each interview, the investigator took detailed notes to document relevant information. We met throughout the interview stage to discuss any issues that surfaced during the interviews and further refine the interview guide to achieve our research objectives. Two programmes were unable to participate in an interview but agreed to answer the questionnaire by email. Data were stored on password-protected computers with identifiers removed.

Data analysis

We extracted data from the blinded interview responses and the interviewer notes. Responses were grouped uniformly by question and clustered into categories developed on the basis of recurring keywords in participants' responses (communication, patient safety, respect, student characteristics). We are knowledgeable about conducting examinations of this kind and well versed in the content related to the questions, which enabled us to establish trust and rapport with participants and to foster information-rich discussion with the participant.25

We triangulated the data by who reviewed the data, with each researcher providing her interpretations of the findings, and discussing points of assent or dissent.26 During each interview, the interviewer summarized the responses and read them back to the participant to ensure accuracy of interpretation and give the participant an opportunity to comment, allowing for further data triangulation. Triangulating multiple perspectives in this manner enhanced the credibility of our findings.26

Results

There are 11 English-medium university PT programmes in Canada, 9 of which agreed to participate in the study. Two programmes sent information related to professional behaviours but did not directly answer the interview questions. Of the 7 programmes that participated fully in the study, 5 programmes each participated in 1 interview, 1 programme participated in 2 interviews, and 1 programme participated in 4 interviews, for a total of 11 interviews. The number of interviews per programme varied as a result of the variability of OSCEs; we conducted additional interviews in an effort to understand the nuances of these examinations.

Characteristics of the OSCEs

Each programme reported conducting at least one OSCE in the course of the PT programme. The number of OSCEs per programme varied and could not be captured because of incomplete survey responses. Of those that did respond, most reported eight to nine OSCEs, with midterm and final assessments in each course; four programmes reported holding a comprehensive or “grand” OSCE at the end of the program.

OSCEs varied, both within and across programmes, with respect to number of stations; length of time per station; content of station; type of examiner; type of model; and use of checkboxes, global rating scales, or both. The number of stations in individual OSCEs varied from 1 to 10; half of the participants reported 3–4 stations per OSCE. The time per station varied from 5 to 15 minutes (including time for reading the question). All programmes reported evaluating only practical skills during the OSCE, with the exception of one programme that reported using a post-encounter station and another that used a reflection station in one assessment. All programmes reported using a blend of faculty and clinicians or teaching assistants as examiners. The type of model patient used during the examination was not consistent; various programmes used PT students, non-PT students, clinicians, and simulated patients. All reported using checkbox-style assessment forms; 2 combined these with global rating scales, but none reported using global rating scales exclusively.

Professional behaviours

All programmes reported evaluating aspects of professional behaviour in the context of their OSCEs. The specific aspects evaluated varied both within and across programs. A total of 31 items were identified, clustered into four categories. The majority (n=14) fell into the category of communication (e.g., “introduces self to patient,” “uses concise verbal communication”); 10 fell into the category of respect (e.g., “consideration of patient dignity, including appropriate draping,” “makes effort to build rapport”). An additional three items were clustered under patient safety (e.g., “ongoing monitoring of patient response”). The final four items were grouped as PT characteristics (e.g., “demonstrates confidence,” “presents a professional appearance”). For a full list of behaviours, see Box 1.

Box 1.

Thirty-one professional behaviour items identified by physical therapy educators, grouped by category

| Category | Professional behaviour items identified |

|---|---|

| Communication | • Changes communication style depending on patient's needs and abilities. • Answers questions throughout the session. • Closes the session appropriately. • Confirms patient understanding. • Demonstrates an organized approach. • Explains assessment and treatment techniques using layman's terms. • Introduces self to patient. • Obtains informed consent (includes explanation of assessment and treatment, expected outcomes, possible risks of not participating, and alternatives, answering questions, confirming understanding). • Obtains permission to proceed with interview, assessment, or treatment. • Provides patient education (e.g., home program). • Speaks to patient in calm manner. • Uses appropriate nonverbal communication (e.g., making eye contact). • Uses concise verbal communication. • Uses verbal commands that are appropriate in type and timing. |

| Respect | • Attends appropriately to patient throughout the session. • Considers patient comfort. • Considers patient dignity, including appropriate draping. • Demonstrates active listening. • Demonstrates cultural sensitivity. • Gives opportunity for patient to ask questions. • Makes effort to alleviate patient fears. • Makes effort to build rapport. • Demonstrates sensitivity during patient handling. • Treats patient with positive regard, dignity, respect, and compassion. |

| Patient safety | • Responds appropriately to patient feedback. • Demonstrates ongoing monitoring of patient response. • Ensures patient comfort throughout session. |

| Physical therapy characteristics | • Demonstrates confidence. • Maintains appropriate patient–therapist relationship. • Positions self appropriately throughout the session. • Presents a professional appearance. |

Although all programmes included assessment of professional behaviours in their OSCEs, five programs also reported evaluating professional behaviours in other aspects of their programs. All study participants were from programs at Canadian universities that use the American Physical Therapy Association—Clinical Performance Instrument (APTA-CPI) tool27 to assess students during clinical internships (i.e., the does phase of assessment). The APTA-CPI is a 24-item tool that includes six items designed to assess students' professional practice in a clinical environment.28 Other methods of assessing professional behaviours were reflection exercises (two programmes) and use of videotaped role-plays (two other programmes).

Discussion

Although recognizing that teaching and assessing professional behaviours is an important component of PT curriculum,7 most PT literature has focused on assessing students' professional behaviours in the clinical context. Our study supports Davis's7 conclusion that professional behaviours are important to teach and formally assess. It also follows Miller's11 model that skills and behaviours should be measured in the shows-how phase (i.e., with an OSCE). The professional behaviour items assessed during OSCEs varied across the country; this finding is consistent with those of studies in medical education1 and may be explained by differences in how content is structured in different university curricula. The variability in the examinations themselves (e.g., styles of examination, numbers of stations, time allotted per station) is likely due to the programmes' different assessment needs. Each Canadian university PT programme is unique, delivering curriculum through a different number and length of courses and with different organization of content. Consistent with the literature, however, we found that courses teaching skills rather than knowledge alone were likely to have an embedded skills examination. Some university programmes also ran a grand OSCE, viewed as a cumulative assessment of the skills taught throughout the program.

Despite the variability in the examinations, participants from Canadian PT programmes were consistent in using OSCEs to evaluate shows how in the academic environment. The APTA-CPI tool is used to evaluate does in the clinical environment. Given the progressive nature of these two assessments, it follows that assessment in the does phase would be similar to but more complex than assessment in the shows-how phase, and comparing the 31 items generated by study participants with the items and sample behaviours of the APTA-CPI confirmed that this is the case. In a study evaluating the psychometric properties of the APTA-CPI, authors used exploratory factor analysis to create subscales of the tool.28 Following this analysis, six of the items were placed into the Professional Practice subscale.28 Four of these items—1, safety; 2, responsible behaviour; 3, professional behaviour; and 8, individual–cultural differences—were similar to our cluster categories. There was also some alignment between the APTA-CPI sample behaviours and our clustered items; for example, one of the seven sample behaviours in Item 2 was similar to our findings (“Wears attire consistent with expectations”27), and two of the nine sample behaviours in Item 3 (e.g., “Maintains patient privacy and modesty”27) were similar (see Box 2). The remaining sample behaviours for these items are more complex in nature (e.g., “Accepts responsibility,”27 “Maintains productive working relationships”27) and are more appropriately evaluated in the clinical environment.

Box 2.

Examples of the relationship between items and sample behaviours on the APTA-CPI tool27 with the 31 professional behaviour items generated related to OSCE assessment

| Examples of APTA-CPI Items and sample behaviours that are similar | Examples of APTA-CPI Items that did not appear in the sample behaviour items related to OSCE assessment |

|---|---|

| Item 1: Practices in a safe manner that minimizes risk to patient self and others. | |

| • Recognizes physiological and psychological changes in patients and adjusts treatment accordingly. | • Observes health and safety regulations. |

| Item 2: Presents self in a professional manner | |

| • Wears attire consistent with expectations of the practice setting. | • Accepts responsibility for own actions. • Demonstrates initiative. |

| Item 3: Demonstrates professional behaviour during interactions with others | |

| • Treats others with positive regard, dignity, respect, and compassion. • Maintains patient privacy and modesty (e.g., draping and confidentiality). |

• Accepts criticism without defensiveness. |

| Item 6: Communicates in ways that are congruent with situational needs. | |

| • Communicates, verbally and nonverbally, in a professional and timely manner. | • Initiates communication in difficult situations. |

| Item 8: Adapts delivery of physical therapy care to reflect respect for and sensitivity to individual differences. | |

| • Exhibits sensitivity to differences in race, creed … in communicating with others. | • Exhibits sensitivity to differences in race, creed … in developing plans of care. |

APTA–CPI=American Physical Therapy Association—Clinical Performance Instrument; OSCE=objective structured clinical examination.

An additional behaviour identified in our study also aligns with one other item on the APTA-CPI tool: Item 6 related to communication. Communication was not included in any of the three subscales after the factor analysis.28 As expected, our study generated communication items because the definition of professional behaviour is often contextualized by the interaction between the health care provider and the patient or client, which by definition cannot ignore elements of communication. This blending of elements related to professional behaviours has been noted in previous reviews in which communication skills, ethics, interpersonal skills, or patient relations were seen as a part of the professional behaviour elements being assessed rather than as distinct categories.1,19–22 In the Essential Competency Profile for Physiotherapists in Canada,2 the interwoven nature of these behaviours is seen in the role descriptions of both communicator and professional. The role of communicator is presented as the vehicle for achieving professional relationships; the role of professional has respect as one of its three key competencies.2

Our findings suggest that all participant programmes use OSCEs to assess some elements of professional behaviour and use checkboxes or item score lists to capture the skills demonstrated. Two programmes also used global rating scales. There are challenges to using checklist scoring to assess professional behaviours in an OSCE format because they only allow the examiner to mark the item as completed or not. They also do not capture the nuances of how well the item was done, omitting valuable formative information that students could use to modify behaviour.

Our study generated 31 individual professional behaviour items, which further emphasizes the complexity of professional behaviours. Individual programmes must determine which professional behaviour items are important, relevant, and feasible to assess in the context of their own OSCEs.

This study evaluated the practice of measuring professional behaviours in the context of an OSCE. Although our goal was to undertake a national review of current practice of English-medium university PT programs in Canada, we were unable to engage all eligible programs. In addition, because of the sample method used, the number of participants per program varied, which may have given some programs more voice in or influence on the results than others. Finally, interviews were not audiotaped, and therefore the potential for incomplete data exists.

Conclusion

The information gathered from this study will inform our practice of assessing professional behaviours in the context of an OSCE. All Canadian entry-level PT programmes surveyed in this study assessed professional behaviours using OSCE-type examinations. Although there was some variability in the OSCEs themselves, which may be related to the structures of different curricula, there is commonality in the choice of items considered important in assessing professionalism. The complexity of assessing professional behaviours is reflected in the fact that study participants generated 31 items for consideration. When determining the appropriate behaviours to assess in the shows-how phase of assessment, it is important to consider the needs of the student, the program, and the clinical community.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

Teaching and assessing professional behaviours is important and valued in PT education. However, no published studies have examined how these behaviours are assessed in the academic environment.

What this study adds

To our knowledge, this study is the first to look at the role of the OSCE in assessing professional behaviours among PT students. All participating Canadian programmes reported using OSCEs to assess professional behaviours, although there was wide variability in the structure and content of OSCEs within and across programs. A total of 31 sample behaviours were identified, clustered into four categories, for measurement of professional behaviours in the context of an OSCE.

Physiotherapy Canada 2015; 67(1);69–75; doi:10.3138/ptc.2013-72

References

- 1.Arnold L. Assessing professional behavior: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):502–15. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200206000-00006. Medline:12063194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Physiotherapy Advisory Group et al. Essential competency profile for physiotherapists in Canada [Internet] Location: Publisher; 2009. [cited 2013 Oct 24]. Available from: http://www.physiotherapyeducation.ca/Resources/Essential%20Comp%20PT%20Profile%202009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.May WW, Morgan BJ, Lemke JC, et al. Model for ability-based assessment in physical therapy education. J Phys Ther Educ. 1995;9(1):3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jette DU, Portney LG. Construct validation of a model for professional behavior in physical therapist students. Phys Ther. 2003;83(5):432–43. Medline:12718709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman J, Rogers J. A comparison of rank ordered professional attributes by clinical supervisors and allied health students. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2010;8(3):1–4. Available from: http://ijahsp.nova.edu/articles/Vol8Num3/pdf/freeman.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bossers A, Kernaghan J, Hodgins L, et al. Defining and developing professionalism. Can J Occup Ther. 1999;66(3):116–21. doi: 10.1177/000841749906600303. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000841749906600303. Medline:10462884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis DS. Teaching professionalism: a survey of physical therapy educators. J Allied Health. 2009;38(2):74–80. Medline:19623788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern DT, Papadakis M. The developing physician—becoming a professional. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(17):1794–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054783. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra054783. Medline:17065641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Mook WN, van Luijk SJ, O'Sullivan H, et al. General considerations regarding assessment of professional behaviour. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(4):e90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.11.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2008.11.011. Medline:19524166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Mook WN, Gorter SL, O'Sullivan H, et al. Approaches to professional behaviour assessment: tools in the professionalism toolbox. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20(8):e153–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.07.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2009.07.012. Medline:19892295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9 Suppl):S63–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. Medline:2400509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain SS, Nadler S, Eyles M, et al. Development of an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) for physical medicine and rehabilitation residents. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;76(2):102–6. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199703000-00003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002060-199703000-00003. Medline:9129514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harden RM, Gleeson FA. Assessment of clinical competence using an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) Med Educ. 1979;13(1):39–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1979.tb00918.x. Medline:763183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regehr G, Freeman R, Hodges B, et al. Assessing the generalizability of OSCE measures across content domains. Acad Med. 1999;74(12):1320–2. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199912000-00015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199912000-00015. Medline:10619010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pieters HM, Touw-Otten FWWM, De Melker RA. Simulated patients in assessing consultation skills of trainees in general practice vocational training: a validity study. Med Educ. 1994;28(3):226–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1994.tb02703.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1994.tb02703.x. Medline:8035715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colliver JA, Swartz MH, Robbs RS, et al. Relationship between clinical competence and interpersonal and communication skills in standardized-patient assessment. Acad Med. 1999;74(3):271–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199903000-00018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199903000-00018. Medline:10099650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prislin MD, Lie D, Shapiro J, et al. Using standardized patients to assess medical students' professionalism. Acad Med. 2001;76(10 Suppl):S90–2. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110001-00030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200110001-00030. Medline:11597884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnabl GK, Hassard TH, Kopelow ML. The assessment of interpersonal skills using standardized patients. Acad Med. 1991;66(9 Suppl):S34–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199109000-00033. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199109000-00033. Medline:1930521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ginsburg S, Regehr G, Hatala R, et al. Context, conflict, and resolution: a new conceptual framework for evaluating professionalism. Acad Med. 2000;75(10 Suppl):S6–11. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200010001-00003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200010001-00003. Medline:11031159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch DC, Surdyk PM, Eiser AR. Assessing professionalism: a review of the literature. Med Teach. 2004;26(4):366–73. doi: 10.1080/01421590410001696434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590410001696434. Medline:15203852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287(2):226–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.2.226. Medline:11779266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veloski JJ, Fields SK, Boex JR, et al. Measuring professionalism: a review of studies with instruments reported in the literature between 1982 and 2002. Acad Med. 2005;80(4):366–70. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200504000-00014. Medline:15793022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, et al. Designing clinical research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Task Force for the Development of Student Clinical Performance Instruments; American Physical Therapy Association. The development and testing of APTA clinical performance instruments. Phys Ther. 2002;82(4):329–53. Medline:11922850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams CL, Glavin K, Hutchins K, et al. An evaluation of the internal reliability, construct validity, and predictive validity of the Physical Therapists Clinical Performance Instrument (PT CPI) J Phys Ther Educ. 2008;22(2):42–50. [Google Scholar]