ABSTRACT

Arenaviruses have a significant impact on public health and pose a credible biodefense threat, but the development of safe and effective arenavirus vaccines has remained elusive, and currently, no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-licensed arenavirus vaccines are available. Here, we explored the use of a codon deoptimization (CD)-based approach as a novel strategy to develop live-attenuated arenavirus vaccines. We recoded the nucleoprotein (NP) of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) with the least frequently used codons in mammalian cells, which caused lower LCMV NP expression levels in transfected cells that correlated with decreased NP activity in cell-based functional assays. We used reverse-genetics approaches to rescue a battery of recombinant LCMVs (rLCMVs) encoding CD NPs (rLCMV/NPCD) that showed attenuated growth kinetics in vitro. Moreover, experiments using the well-characterized mouse model of LCMV infection revealed that rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 were highly attenuated in vivo but, upon a single immunization, conferred complete protection against a subsequent lethal challenge with wild-type (WT) recombinant LCMV (rLCMV/WT). Both rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 were genetically and phenotypically stable during serial passages in FDA vaccine-approved Vero cells. These results provide proof of concept of the safety, efficacy, and stability of a CD-based approach for developing live-attenuated vaccine candidates against human-pathogenic arenaviruses.

IMPORTANCE Several arenaviruses cause severe hemorrhagic fever in humans and pose a credible bioterrorism threat. Currently, no FDA-licensed vaccines are available to combat arenavirus infections, while antiarenaviral therapy is limited to the off-label use of ribavirin, which is only partially effective and is associated with side effects. Here, we describe the generation of recombinant versions of the prototypic arenavirus LCMV encoding codon-deoptimized viral nucleoproteins (rLCMV/NPCD). We identified rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 to be highly attenuated in vivo but able to confer protection against a subsequent lethal challenge with wild-type LCMV. These viruses displayed an attenuated phenotype during serial amplification passages in cultured cells. Our findings support the use of this approach for the development of safe, stable, and protective live-attenuated arenavirus vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

Arenaviruses cause chronic infections of rodents across the world, and human infections occur through mucosal exposure to aerosols or by direct contact of abraded skin with infectious materials (1). Several arenaviruses, chiefly Lassa virus (LASV), the causative agent of Lassa fever (LF) in West Africa, and Junín virus (JUNV), the causative agent of Argentine hemorrhagic fever (AHF) in Argentina, cause hemorrhagic fever (HF) disease in humans that is associated with high morbidity and significant mortality and pose important public health problems in their areas of endemicity (1–3). Notably, increased travel has led to the importation of LF cases into metropolitan areas around the globe where LASV is not endemic (1, 4, 5). Moreover, the recent identification of two novel HF-causing arenaviruses, Chapare virus in Bolivia (6) and Lujo virus in South Africa (7), have raised concerns about newly emerging HF arenaviruses. In addition, evidence indicates that the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), distributed worldwide, is a neglected human pathogen of clinical significance (8–10). Moreover, arenaviruses pose a credible biodefense threat, and six of them, including LCMV, LASV, and JUNV, are classified as category A agents (2, 11). Public health concerns posed by human-pathogenic arenaviruses are aggravated by the lack of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved vaccines and the limitation of current antiarenaviral therapy to the off-label use of ribavirin, which is only partially effective and is associated with side effects (12–15). The significance of arenaviruses in human health and biodefense readiness, together with the limited existing armamentarium to combat them, highlights the urgent need to develop vaccines and therapies to combat human-pathogenic arenaviruses.

Candid no. 1, a JUNV live-attenuated strain, has been shown to be an effective vaccine against AHF (16), but outside Argentina, Candid no. 1 has achieved only investigational new drug status (17), and yet unpublished studies done by Paessler and colleagues at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB)—Galveston have shown that Candid no. 1 does not protect against LF. Moreover, there is only limited information regarding long-term protective immunity conferred by Candid no. 1. Likewise, although cases of reversion of Candid no. 1 to a more virulent strain have not been reported, its phenotypic stability remains uncertain, as a single amino acid change on the viral glycoprotein (GPC) can affect JUNV virulence (18, 19). Likewise, there is evidence suggesting the potential genetic and phenotypic instability of the existing Candid no. 1 vaccine strain of JUNV (20).

Despite significant efforts to develop vaccines against LF, not a single LASV vaccine candidate has entered a clinical trial. However, the Mopeia virus (MOPV)/LASV reassortant ML29 has shown promising safety and efficacy profiles in animal models, including nonhuman primates (21–23), but limited knowledge about the mechanisms of ML29 attenuation has raised the concern that additional ML29 mutations, or reassortants between ML29 and circulating LASV strains, could result in viruses with enhanced virulence. Likewise, a replication-competent attenuated recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) expressing LASV glycoprotein has been reported to elicit protective immune responses in nonhuman primates against a lethal LASV challenge (24). Nevertheless, epidemiological studies indicate that the most feasible approach to control LF would be a live-attenuated vaccine, due to the ability to induce robust and long-term cellular and humoral immune responses following a single immunization (3, 25, 26).

Redundancy in the genetic code results in many amino acids being encoded by more than one codon (27). A codon usage bias exists where synonymous codons are used at different frequencies by an organism to incorporate the same amino acid residue into a protein (28). Codon optimization is a frequently used strategy to improve expression of genes in heterologous systems (29–32), whereas all mammals exhibit essentially the same codon bias (33, 34). Conversely, replacement of commonly used codons with nonpreferred codons, or codon deoptimization (CD), can dramatically decrease gene expression (35). Proteins encoded by mammalian viruses are subjected to the codon usage bias of the cells they infect; therefore, CD is predicted to adversely affect viral protein translation, which could result in viral attenuation (36–38). Accordingly, several RNA viruses have been effectively attenuated by CD of a single or a limited number of viral gene products (36–38). In this study, we explored whether the concept of CD-based live-attenuated vaccine could be implemented with the prototypic arenavirus LCMV in a well-characterized mouse model of infection.

Arenaviruses are enveloped viruses with a bisegmented, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome (1). Both the large (L) and small (S) genome RNA segments use an ambisense coding strategy to express two viral proteins. The L segment encodes the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L) and the matrix RING finger (Z) protein, whereas the S segment encodes the nucleoprotein (NP) and glycoproteins GP1 and GP2, which mediate virus receptor recognition and cell entry (1). NP is the most abundant viral polypeptide in infected cells and virions and the main component of the virus ribonucleoprotein (vRNP), which directs replication and transcription of the viral genome (1). NP interacts with Z to mediate the incorporation of vRNPs into mature infectious virions (39, 40), and NP has also been shown to counteract the cellular host type I interferon (IFN-I) response (41–46). Because NP has multiple critical functions in the arenavirus life cycle, we chose to investigate if CD of NP resulted in viruses that were highly attenuated in vivo but still able to afford protection against a subsequent challenge with wild-type (WT) recombinant LCMV (rLCMV/WT). For this, we used reverse-genetics (47–49) and CD (33–35) approaches to rescue recombinant LCM viruses with different degrees of CD NPs (rLCMV/NPCD). We present evidence that the magnitude of CD of LCMV NP correlated with its reduced expression and functional activity. Likewise, we show that it is feasible to rescue rLCMV encoding CD NPs that exhibit modestly reduced growth properties in cultured cells, whereas in vivo they are highly attenuated and able to confer efficient protection against a lethal challenge with rLCMV/WT. These results raise the possibility of using a similar CD approach for the design of live-attenuated vaccines for the prevention of HF disease caused by human-pathogenic arenaviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Human lung adenocarcinoma epithelial (A549; ATCC CCL-185), human embryonic kidney (293T; ATCC CRL-11268), African green monkey kidney epithelial (Vero; ATCC CCL-81), and baby hamster kidney (BHK-21; ATCC CCL-10) cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Mediatech, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 units/ml) and maintained in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. Recombinant LCMV (Armstrong strain; ARM53b) and wild-type (rLCMV/WT) and CD NP (rLCMV/NPCD) viruses were rescued and propagated in BHK-21 cells as described previously (48). Sendai virus (SeV), Cantell strain, was grown in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs (50).

Plasmids.

Hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged LCMV NP (51) and LCMV L (52) pCAGGS expression plasmids have been described previously. Generation of fully CD LCMV NP (LCMV NPCD) was done by de novo synthesis in which each wild-type codon was replaced with the codon least represented in mammalian genomes (Biomatik). LCMV NPCD was amplified by PCR and cloned into pCAGGS HA-COOH (51) using SacI and KpnI restriction enzymes. To generate LCMV NPCD chimeras, restriction sites were used to subclone LCMV NPWT PCR products into LCMV NPCD. Plasmids for the rescue of rLCMV/NPCD were obtained by amplifying LCMV NPCD from pCAGGS HA-COOH and cloning into the mouse pPol-I GP/BbsI vector plasmid (47, 49). All plasmids were generated using standard cloning techniques. The primers used to generate the described plasmid constructs are available upon request. Plasmid constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (ACGT).

Immunofluorescence assays (IFA).

To evaluate LCMV NPCD protein expression, 293T cells (1.8 × 105 cells/well; 24-well plate format) were transiently transfected in suspension with 1 μg of LCMV NP expression plasmids using LPF2000 (Invitrogen). Empty-plasmid-transfected cells were included as a negative control. LCMV NPWT was used as a positive control. At 48 h posttransfection (p.t.), cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked using 2.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) diluted in 1× PBS. After blocking, the cells were incubated with an anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Sigma) and probed with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody (Dako). LCMV NP expression was observed under a Leica fluorescence microscope (40). The microscope images were colored using Adobe Photoshop CS4 (v11.0) software.

Protein gel electrophoresis and Western blot (WB) analysis.

Human 293T cells (3 × 106 cells/well; 6-well plate format) were transiently transfected in suspension with 1 μg of the indicated LCMV NP pCAGGS expression plasmid. Empty- and LCMV NPWT plasmid-transfected cells were included as negative and positive controls, respectively. At 48 h p.t., cells were collected and lysed with 400 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, and a complete cocktail of protease inhibitors [Roche]). A 20-μl aliquot of the total cell lysates was separated on SDS-12% PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were incubated with an anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Sigma) and probed with a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (GE Healthcare). LCMV NP expression was detected using a chemiluminescence kit (Denville Scientific). Cellular GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was used to normalize the amount of lysates and was detected using a polyclonal antibody to GAPDH (Abcam). Protein band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH) (51). Band quantifications were normalized according to GAPDH expression, assigning 100% intensity to LCMV NPWT. LCMV NPCD expression levels were then normalized by their intensity relative to that of LCMV NPWT.

MG assay.

Human 293T cells (6.5 × 105 cells/well; 12-well plate format; triplicates) were cotransfected using LPF2000 with 0.6 μg of pCAGGS L, 0.15 μg of the indicated pCAGGS LCMV NP constructs or empty plasmid, 0.5 μg of a green fluorescent protein (GFP), a Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) dual-reporter minigenome (MG) plasmid driven by a human polymerase I promoter (hpPol-I GFP/Gluc) (47), and 0.1 μg of a mammalian expression vector encoding Cypridina luciferase (Cluc) under the control of the constitutively active simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter (pSV40-Cluc; New England BioLabs) (53) to normalize transfection efficiencies. An empty pCAGGS plasmid was used to keep the amount of transfected plasmid DNA constant (47). At 48 h p.t., reporter gene expression was assessed by fluorescence microscopy (GFP) using a Leica fluorescence microscope and luciferase activity (Gluc) was assessed using a Lumicount luminometer (Packard) (47). The microscope images were colored using Adobe Photoshop CS4 (v11.0) software. Luciferase gene activities were determined using the Biolux Gaussia and Cypridina Luciferase Assay kits (New England BioLabs). Reporter gene activation (Gluc) is indicated as fold induction over the negative pCAGGS empty-plasmid control (47). The mean value and standard deviation were calculated and statistical analysis using a two-tailed Student t test was done using Microsoft Excel software.

IFN-I inhibition assays.

The fluorescence- and luminescence-based assays to evaluate the activity of LCMV NP counteracting the induction of IFN-I production have been described previously (42–44). Briefly, 293T cells (4 × 105 cells/well; 12-well plate format; triplicates) were cotransfected with 1 μg of the firefly luciferase (Fluc) reporter gene driven by the beta interferon (IFN-β) promoter (pIFNβ-Fluc), 1 μg of the GFP/chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene driven by the IFN-β promoter (pIFNβ-GFP/CAT), 0.15 μg of the indicated LCMV NP pCAGGS expression plasmids, and 0.1 μg of a Renilla luciferase (Rluc) reporter gene under the control of an SV40 promoter (pRL SV40; Promega) to normalize for transfection efficiencies, using a calcium phosphate-based mammalian transfection kit (Stratagene) (42–44). After overnight transfection, cells were infected with Sendai virus, Cantell strain (50), for an additional 24 h. IFN-β gene promoter activation was then evaluated by GFP expression using a Leica microscope and by Fluc activity using the Dual Luciferase reporter kit (Promega). Reporter gene activation is shown as relative light units (RLU) compared to SeV-infected cells in the absence of LCMV NP (empty plasmid). The mean value and standard deviation were calculated and statistical analysis using a two-tailed Student t test was done using Microsoft Excel software.

Virus rescues and growth kinetics.

All the rLCM viruses used in this study are based on the ARM53b strain (54). To rescue rLCMV, BHK-21 cells (1 × 106 cells/well; 6-well plate format) were cotransfected with 0.8 μg of pCAGGS NP, 1 μg of pCAGGS L, 1.4 μg of the mouse pPol-I L, and 0.8 μg of the mouse pPol-I S containing LCMV NPCD, using LPF2000 (48). At 12 h p.t., the medium was replaced with 2 ml of postinfection medium (a 1:2 ratio of 10% FBS DMEM and Opti-MEM). At 72 h p.t., the cells were trypsinized, scaled up into 10-cm dishes, and maintained for 3 days before tissue culture supernatants (TCS) were collected and assessed for the presence of virus (47). Briefly, serial dilutions of TCS were used to infect Vero cells (4 × 104 cells/well; 96-well plate format; triplicates), and titers were determined as focus-forming units (FFU)/ml (47) using an LCMV NP-specific monoclonal antibody (clone 1.1.3) (55). To evaluate viral growth kinetics, BHK-21, A549, and Vero cells (1.25 × 105 cells/well; 24-well plate format; triplicates) were infected (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 0.01) and TCS were collected at the indicated time points and titrated as described above. The mean value and standard deviation were calculated using Microsoft Excel software.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

BHK-21 cells (5 × 105 cells/well; 6-well plate format) were infected (MOI, 0.01), and at 72 h p.i., total cellular RNA was prepared using TRIzol (Invitrogen). Random hexamers were used for initial cDNA synthesis using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified by PCR using a combination of LCMV NPWT- or NPCD-specific primers. The amplified gene products were examined on a 1% agarose DNA gel and analyzed by sequencing (ACGT).

Viral stability.

Vero cells (1 × 106 cells/well; 6-well plate format) were infected (MOI, 0.1), and at 48 h p.i., TCS were collected and diluted 1:10 in reduced-serum cell medium (2% DMEM) before subsequent infections in Vero cells. Infected cells from each passage were collected for RNA extraction, and LCMV NP was amplified by RT-PCR and sequenced (ACGT).

Mouse experiments.

To evaluate the virulence of rLCMV/NPCD chimeras in vivo, B6 mice (6-week old immunocompetent males; n = 8) were infected intracranially (i.c.) (103 PFU) with each of the indicated rLCM viruses. The mice were monitored daily for development of clinical symptoms and survival for 12 days. To evaluate the protection efficacy of rLCMV/NPCD, mice were immunized with PBS or with either rLCMV/WT or rLCMV/NPCD intraperitoneally (i.p.) (105 PFU; n = 8). At 4 weeks postinfection, the mice were lethally challenged with rLCMV/WT (i.c.; 103 PFU) and monitored for development of clinical symptoms and survival over 12 days. All animal experiments were done under protocol 09-0137 and approved by The Scripps Research Institute IACUC.

RESULTS

Effect of CD on LCMV NP expression and function.

We selected NP as a target to examine the potential of a CD-based approach for the generation of an LCMV live-attenuated arenavirus vaccine, because NP plays critical roles in viral RNA replication and gene transcription (1, 39, 52) and contributes to LCMV's ability to counteract the host IFN-I response to viral infection (41–45, 56, 57).

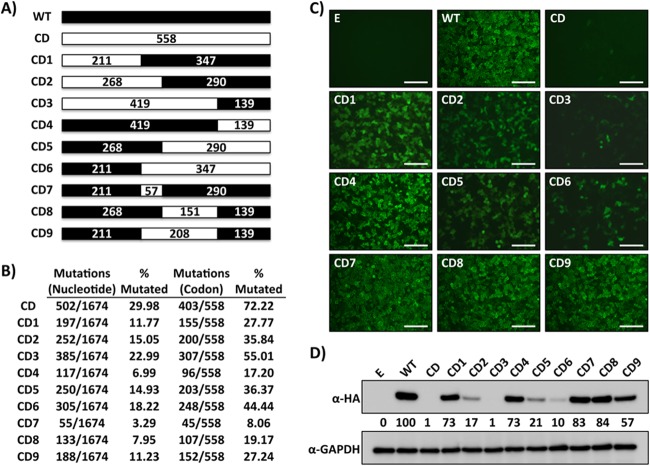

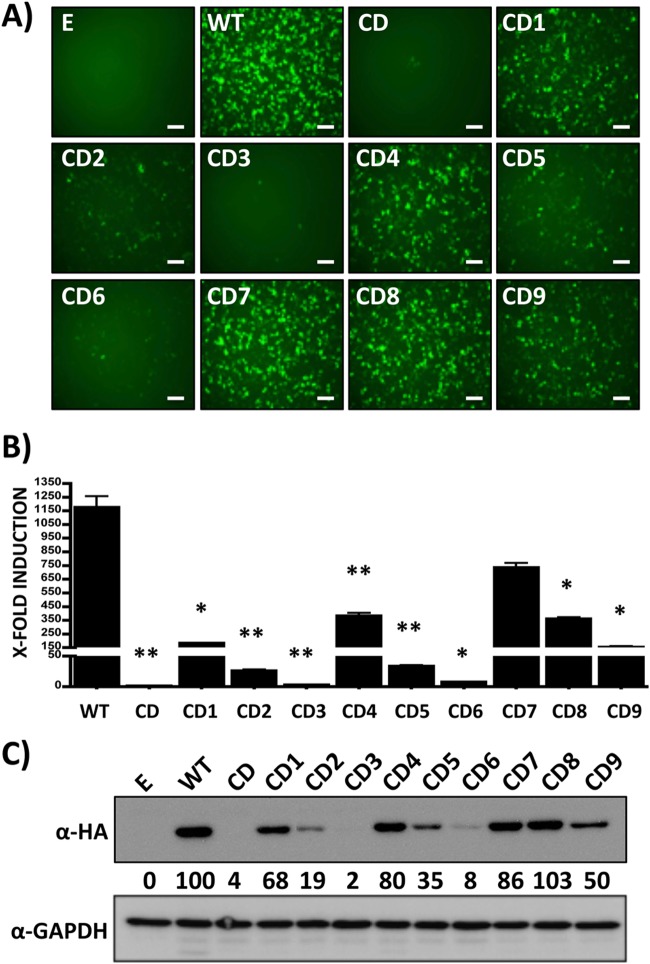

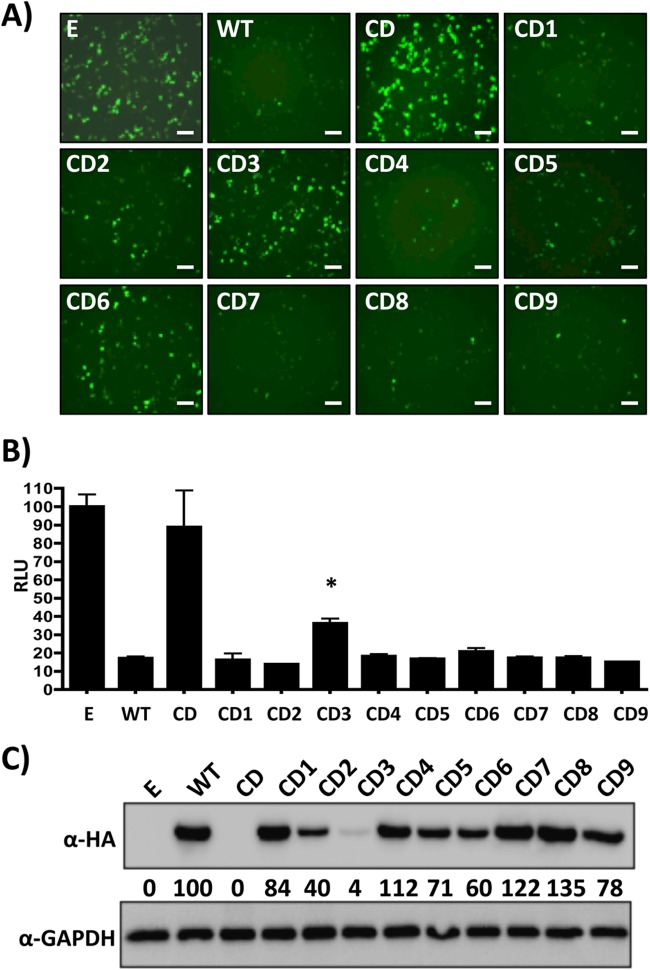

To evaluate the effect of CD on LCMV NP expression and function, we reengineered its open reading frame (ORF) by incorporating at each amino acid position the least frequently used codon in mammalian cells but preserving the intact LCMV NPWT amino acid sequence (Fig. 1A; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). For this, we synthesized de novo the NP cDNA to introduce a total of 502 nucleotides of silent mutations into the LCMV NP ORF, which affected 403 out of 558 amino acids (72.22%) (Fig. 1B). The resulting LCMV NPCD was cloned into the pCAGGS protein expression plasmid, which provided an HA tag at the C terminus (51). Expression levels of LCMV NPCD were significantly reduced in human 293T cells, as determined by IFA and WB assays (Fig. 1C and D). Accordingly, reduced NP expression levels in cells transfected with LCMV NPCD, compared to cells transfected with the same amount of plasmid expressing LCMV NPWT, correlated with a dramatic decrease of NP activity in viral replication and transcription using an MG rescue assay (47, 49, 52) (Fig. 2), as well as in its ability to inhibit activation of the IFN-β promoter in a cell-based reporter assay (42–44) (Fig. 3).

FIG 1.

Characterization of CD LCMV NP chimeras. (A) Schematic representation of LCMV NPCD chimeras. Wild-type LCMV NP (NPWT) regions are represented by black boxes. The white boxes represent LCMV NPCD. The numbers indicate the amino acid lengths of the respective regions. (B) Nucleotide and amino acid changes in LCMV NPCD chimeras. The discrepancies between mutated codons and the amino acid lengths indicated in panel A are due to codons that are already deoptimized in LCMV NPWT or that encode either methionine or tryptophan. (C and D) LCMV NPCD chimera expression levels. Human 293T cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids encoding LCMV NPCD chimeras and evaluated at 48 h p.t. for protein expression by IFA (C) and WB (D) using an anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody. Empty plasmid (E) and LCMV NPWT were included as negative and positive controls, respectively. GAPDH expression levels were used as loading controls. Representative images of three independent transfection experiments are shown. (D) The numbers indicate the percentages of LCM NPCD expression compared to that of LCMV NPWT after normalization with GAPDH. (C) Scale bars = 100 μm.

FIG 2.

Functional characterization of LCMV NPCD chimeras in viral replication and transcription. Human 293T cells were transiently cotransfected (triplicates) with the indicated pCAGGS LCMV NPCD expression plasmids, together with pCAGGS LCMV L, the human LCMV MG plasmid pPol-I GFP/Gluc, and an SV40 Cypridina luciferase expression plasmid (pSV40-Cluc), to normalize transfection efficiencies. (A and B) At 48 h p.t., MG activities were evaluated by GFP (A) and Gluc (B) expression. Representative images of three independent transfections are shown. Luciferase activity is represented as fold induction over cells transfected with empty plasmid (E) in place of LCMV NP. The error bars indicate standard deviations. *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.005. (C) LCMV NPCD expression levels in collected total cell lysates were determined by WB using an anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody and an HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse polyclonal antibody. GAPDH was included as a loading control. The numbers indicate the percentages of LCMV NPCD expression compared to that of LCMV NPWT after normalization to GAPDH. Scale bars, 100 μm.

FIG 3.

Inhibition of IFN-β promoter activation by LCMV NPCD chimeras. Human 293T cells were transiently cotransfected with the indicated pCAGGS LCMV NPCD expression plasmids, along with pIFNβ-GFP/CAT and pIFNβ-Fluc, and an SV40-driven Renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL SV40) to normalize transfection efficiencies. At 24 h p.t., the cells were infected with SeV (MOI, 3), and 24 h later, IFN-β promoter activity was determined by GFP (A) and Fluc (B) activities. (A) Mean values and standard deviations are shown. Statistical analysis using a two-tailed Student t test was done using Microsoft Excel software. *, P ≤ 0.05. (B) Representative images of three independent transfections are shown. Luciferase activity is represented as RLU normalized to cells transfected with empty plasmid (E) in place of LCMV NP. (C) LCMV NPCD expression levels in total cell lysates were determined by WB using GAPDH as a loading control. The numbers indicate the percentages of LCMV NPCD expression compared to that of LCMV NPWT after normalization with GAPDH. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Functional characterization of LCMV NPCD chimeric constructs.

The strong decrease in expression and function of LCMV NPCD suggested that rescue via reverse genetics of rLCMV containing the NPCD ORF (rLCMV/NPCD) might not be feasible, which was confirmed by our several independent failed attempts to rescue rLCMV/NPCD (data not shown). We reasoned that this obstacle could be overcome by finding a level of CD that resulted in NP expression levels compatible with the generation of a viable rLCMV. We therefore generated a collection of chimeric constructs containing varying lengths of CD sequences at the N terminus (NPCD1–3) and C terminus (NPCD4–6) and the central region (NPCD7–9) of LCMV NP (Fig. 1A and B), all containing a C-terminal HA tag to facilitate their detection (51). Next, we examined the correlation between the expression levels of these LCMV NPCDs and their degrees of CD by IFA (Fig. 1C) and WB (Fig. 1D). Constructs NPCD1, NPCD4, NPCD7, NPCD8, and NPCD9, which contained <30% CD, displayed expression levels similar to those obtained with a construct expressing LCMV NPWT. On the other hand, constructs NPCD2, NPCD5, and, to a lesser extent, NPCD6, which contained 30 to 50% CD, were moderately affected in protein expression, whereas LCMV NPCD3, containing ∼55% CD, was severely affected in its expression, to levels comparable to those of LCMV NPCD. We next examined whether the magnitude of the effect on protein expression caused by the different degrees of CD correlated, as predicted, with the effects observed on LCMV NP functional activities. For this, we evaluated the activities of the LCMV NPCD chimeric constructs in the MG rescue assay (47, 49, 52) and in cell-based reporter assays that measured IFN-β promoter activation (42–44). Levels of viral replication and gene expression of the MG, as determined by GFP expression (Fig. 2A) and Gaussia luciferase activity (Fig. 2B), correlated with the degree of CD and protein expression afforded by each LCMV NPCD construct (Fig. 2C).

LCMV (and other arenavirus) NP has been shown to block IFN-I induction during viral infection (42–44). This anti-IFN activity of arenavirus NP has been attributed to a recently identified 3′-5′ exoribonuclease domain in the C terminus of NP, which is thought to digest double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) substrates formed during viral replication in an attempt to mask infection from cellular detection (56–60). Thus, we evaluated whether reduced protein expression levels would affect the abilities of different NP chimeras to inhibit SeV-mediated activation of an IFN-β promoter (42–44). The magnitude of LCMV NPCD-mediated inhibition of IFN-β promoter activation in response to SeV infection, as determined by GFP expression (Fig. 3A) or firefly luciferase activity (Fig. 3B), correlated with LCMV NP expression levels (Fig. 3C). These results demonstrated that the degree of CD (NPWT > NPCD7 > NPCD4 > NPCD8 > NPCD1 = NPCD9 > NPCD2 = NPCD5 > NPCD6 > NPCD3 > NPCD) correlated well with reduced levels of LCMV NP expression and its functional activities.

Generation of recombinant viruses expressing LCMV NPCD chimeric constructs (rLCMV/NPCD).

We next used reverse-genetics approaches (47, 49, 52) to rescue rLCMV containing NPs with different degrees of CD that were predicted to be viable based on results from expression and function analyses of the corresponding NPCD constructs. The identity of the rescued rLCMV was confirmed by RT-PCR using RNA extracted from infected BHK-21 cells and primers specific for LCMV NPWT or NPCD (Fig. 4), followed by sequencing of the amplified PCR products (data not shown). We evaluated the growth kinetics of the rescued rLCMV/NPCD in BHK-21 (Fig. 5A), A549 (Fig. 5B), and Vero (Fig. 5C) cells. We observed a correlation between the expression levels of LCMV NPCD chimeras and their ability to replicate in the different cell lines (rLCMV/NPCD7 > rLCMV/NPCD8 > rLCMV/NPCD9 > rLCMV/NPCD1 > rLCMV/NPCD2). Importantly, rLCMV/NPCD7, rLCMV/NPCD8, and rLCMV/NPCD9 were slightly attenuated compared with rLCMV/WT. As expected, based on the degree of CD, rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 were the most attenuated rLCM viruses in all the cell lines tested. Interestingly, viral attenuation was more pronounced in A549 cells than in Vero or BHK-21 cells. These differences could be due to species-specific codon usage (CD was based on mammalian codon usage), tRNA availability in the different cell lines, or a decrease in viral fitness in IFN-I-competent A549 cells compared to IFN-I-deficient BHK-21 and Vero cells (42, 61). Intriguingly, rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 kinetics were very similar in all three cell lines tested, while their expression levels (Fig. 1) and their activities in the minigenome assay (Fig. 2) using plasmid-based transfections seemed different.

FIG 4.

Confirmation of rLCMV/NPCD. (A) Schematic representation of rLCMV/NPCD rescued viruses. Wild-type LCMV NP regions are represented by black boxes. The white boxes represent LCMV NPCD. The numbers indicate the amino acid lengths of the respective regions. (B) Genetic characterization of rLCMV/NPCD. BHK-21 cells were mock infected or infected (MOI, 0.01) with either rLCMV/NPWT or rLCMV/NPCD chimeras. At 72 h p.i., cells were collected and rLCM viruses were characterized by RT-PCR using the indicated primers. The RT-PCR products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel.

FIG 5.

rLCMV/NPCD growth kinetics. BHK21 (A), A549 (B), and Vero (C) cells were infected with the indicated viruses (MOI, 0.01), and viral titers in TCS were determined by immunofocus assay (FFU/ml) at the indicated times postinfection. The dashed lines indicate the limit of detection (20 FFU/ml).

Safety and protective efficacy of rLCMV/NPCD viruses.

To assess the potential use of a CD-based approach for the development of arenavirus live-attenuated vaccine candidates, we evaluated the virulence and protective efficacies of selected rLCMV/NPCD in vivo using the well-characterized mouse model of LCMV infection. To that end, we infected 6-week-old male B6 mice i.c. with 103 PFU of rLCMV/WT, rLCMV/NPCD1, rLCMV/NPCD2, and rLCMV/NPCD7 (Table 1). As predicted, by day 6 p.i., all mice infected with rLCMV/WT developed clinical symptoms of LCM disease and died within 8 days after inoculation. Mice infected with rLCMV/NPCD7 exhibited the same morbidity and mortality as mice infected with rLCMV/WT. In contrast, all mice infected with rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 survived and remained free of clinical symptoms throughout the duration of the experiment (12 days). Moreover, they were fully protected against an i.c. lethal challenge with rLCMV/WT administered 4 weeks after the initial infection (Table 2). These findings indicated that rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 had a highly attenuated phenotype in vivo while retaining the ability to trigger a protective immune response against a subsequent rLCMV/WT lethal challenge. We then assessed whether, in a commonly used protocol of LCMV immunization (105 PFU; i.p. route), rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 were also capable of inducing protective immunity against a subsequent rLCMV/WT lethal challenge (103 PFU, i.c.) (Table 3). All mice immunized i.p. with rLCMV/WT, rLCMV/NPCD1, or rLCMV/NPCD2 survived the challenge and remained free of clinical symptoms throughout the duration of the experiment (12 days). As expected, all mock (PBS)-immunized mice developed severe clinical symptoms and died within 8 days of the i.c. challenge with rLCMV/WT. Altogether, these results demonstrate the feasibility of using rLCMV/NPCD to develop safe and protective live-attenuated vaccines.

TABLE 1.

In vivo attenuation of rLCMV/NPCD correlates with the degree of codon deoptimizationa

| rLCMV | Survival (%) at day p.i.: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 12 | |

| PBS | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| WT | 100 | 37.5 | 0 | |

| CD1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| CD2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| CD7 | 100 | 25 | 0 | |

Six-week-old male B6 mice (n = 8) were infected (i.c; 103 PFU) with the indicated rLCM viruses or inoculated with the virus diluent, PBS. The mice were monitored daily for morbidity and mortality until the experimental endpoint (12 days p.i.).

TABLE 2.

Ability of rLCMV/NPCD to protect against an rLCMV/WT lethal challengea

| Primary infection | Survival (%) at day postchallenge: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 12 | |

| PBS | 100 | 0 | ||

| CD1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| CD2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Mice (n = 8) infected (i.c; 103 PFU) with rLCMV/NPCD1 or rLCMV/NPCD2 (Table 1) were fully protected against a subsequent lethal challenge with rLCMV/WT (i.c; 103 PFU). The mice were monitored daily for morbidity and mortality until the experimental endpoint (12 days p.i.).

TABLE 3.

Immunization with rLCMV/NPCD1 or rLCMV/NPCD2 induces protection against a lethal challenge with rLCMV/WTa

| Immunization | Survival (%) at day postchallenge: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 12 | |

| PBS | 100 | 25 | 0 | |

| WT | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| CD1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| CD2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Six week-old male B6 mice (n = 8) were immunized with the indicated viruses (i.p.; 105 PFU) or inoculated with the virus diluent (PBS) and infected for 4 weeks with rLCMV/WT (i.c.; 103 PFU). The mice were monitored daily for morbidity and mortality.

Genetic and phenotypic stability of rLCMV/NPCD.

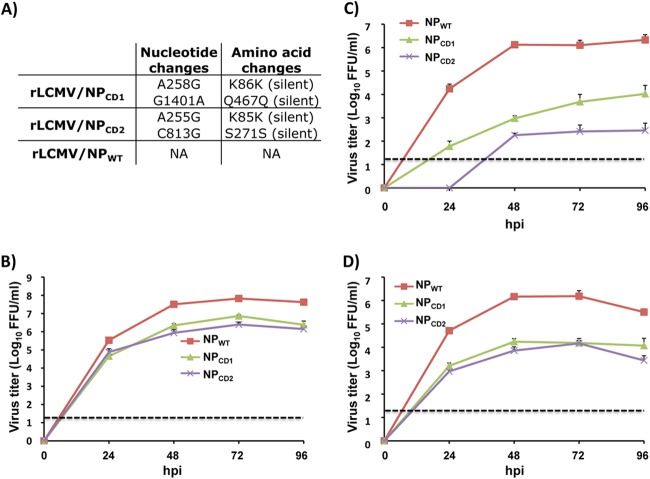

Due to the high mutation rates associated with RNA viruses, it was important to determine that serial passages of attenuated rLCMV/NPCD in Vero cells, which mimics the process of manufacturing and generating stocks of vaccine in an FDA-approved cell line, did not accumulate genetic changes that could affect the attenuated phenotype. To examine this, we conducted serial passages of rLCMV/WT, rLCMV/NPCD1, and rLCMV/NPCD2 in Vero cells and determined the NP sequence at passage 10 (P10) for each of the viruses. We found only two silent mutations in rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 (Fig. 6A). We next assessed whether these mutations in rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 restored rLCMV/WT-like growth properties in cultured cells or altered the in vivo attenuated phenotype. P10 of both rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 exhibited growth kinetics properties in BHK-21 (Fig. 6B), A549 (Fig. 6C), and Vero (Fig. 6D) cells similar to those observed for the corresponding parental rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 viruses. More importantly, all the mice infected (i.c.; 103 PFU) with rLCMV/NPCD1 or rLCMV/NPCD2 P10 survived and remained free of any noticeable clinical symptoms through the entire duration of the study (data not shown).

FIG 6.

Genetic and phenotypic stability of rLCMV NPCD chimeras. (A) Genetic stability. Vero cells were infected (MOI, 0.1) with rLCMV/NPWT, rLCMV/NPCD1, and rLCMV/NPCD2 viruses. At 48 h p.i., TCS were collected and used to infect (1:10 dilution) fresh Vero cells for 10 passages. Total RNA from last-passage (P10)-infected Vero cells was extracted and used for RT-PCR of LCMV NP. The PCR products were sequenced, and the mutations identified in LCMV NP are indicated. (B to D) Growth kinetics. BHK-21 (B), A549 (C), and Vero (D) cells were infected with rLCMV/NPWT, rLCMV/NPCD1, and rLCMV/NPCD2 P10 viruses (MOI, 0.01), and the viral titers at the indicated times postinfection were determined by immunofocus assay (FFU/ml). The error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Genome scale changes in codon pair bias have been successfully used to generate attenuated viruses exhibiting properties amenable for the development of live-attenuated vaccines (36–38). These approaches, however, require the use of computer algorithms to design viral genomes with appropriate pair-deoptimized codons (36–38), and the use of alternative codon pair deoptimization might result in different degrees of attenuation. In this work, we used a more direct approach to engineer rLCMVs in which the majority of the amino acid residues of the viral NP are encoded by the least-preferred codon in mammalian cells, which was predicted to result in reduced protein expression and, therefore, viral attenuation. We selected NP for our initial studies to explore the effect of CD of the arenavirus genome, because NP is the most abundant viral protein present in infected cells and virions (1) and NP also plays many essential roles in the virus life cycle (40, 41, 44, 45, 51). We succeeded in generating a variety of rLCMV/NPCD viruses that were highly attenuated in vivo but able to induce protection against a subsequent lethal challenge with rLCMV/WT.

CD for the generation of live-attenuated vaccine candidates offers several unique advantages over other current strategies. First, a CD live-attenuated vaccine contains hundreds of silent mutations at the nucleotide level that would make viral reversion to a virulent WT phenotype extremely unlikely, if not impossible (36–38). Concern about reversion to a virulent phenotype is particularly important for RNA viruses, because their error-prone replication machinery has the potential for rapid evolution (62). Thus, in the case of the influenza virus live-attenuated vaccines, viral attenuation is produced by 4 amino acid changes in the viral polymerase subunits (K391E, E581G, and A661T in PB1; N265S in PB2) and 1 amino acid change in the viral NP (D34G) (63). These amino acid changes confer a temperature-sensitive phenotype on the virus, allowing its replication only at 33°C (63). Due to the potential to revert to a pathogenic phenotype, as well as the ability to cause symptoms associated with natural influenza virus infection, the influenza virus live-attenuated vaccine is limited to use in healthy individuals 5 to 65 years old with a competent immune system but excluded for use in immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women (64–67). Notably, in the case of the live-attenuated vaccine Candid no. 1 strain of JUNV, a single amino acid mutation in the viral GPC (F427I) (18, 19) has been shown to confer the phenotype of the pathogenic XJ13 strain of JUNV, the causative agent of AHF in humans (68), which raises significant safety concerns. In our studies, 10 sequential passages of rLCMV/NPCD1 and rLCMV/NPCD2 in Vero cells, a cell substrate approved by the FDA for production of human vaccines, resulted in two silent point mutations in each of the viruses that did not affect their attenuated phenotype either in cultured cells or in vivo. Nevertheless, we cannot formally rule out the possibility that accumulation of compensatory mutations during scale-up vaccine production could result in enhanced NP expression and the emergence of a virus genotype associated with increased virulence. Second, CD does not affect the viral protein sequence, and thus, the virus retains an intact antigenic repertoire identical to that of WT virus, which should help to generate comparable B and T cell immune responses. Third, generation of CD live-attenuated vaccine can be rapidly achieved by combining the de novo synthesis of CD genes (or gene segments) with our state-of-the-art plasmid-based reverse-genetics technologies (47–49). Moreover, it should be noted that reassortment between a circulating pathogenic arenavirus strain and a CD live-attenuated arenavirus vaccine it is highly unlikely to result in a genetic combination associated with increased virulence compared to the already circulating pathogenic strain. A similar argument is applicable to potential recombination events between a pathogenic circulating arenavirus strain and its corresponding CD-based live-attenuated arenavirus vaccine. Moreover, it should be noted that the characteristics of the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex responsible for directing RNA replication and gene transcription of negative-strand (NS) RNA viruses, including arenaviruses, determines that recombination events are highly unlikely to occur during multiplication of NS RNA viruses.

Contrary to the situation observed with other viruses slated for CD (36–38), we were not able to generate an rLCMV containing a fully CD NP due to the very low NP expression levels and corresponding reduced functional properties (1). Thus, we first had to identify the optimal degree of CD in LCMV NP that allowed us to rescue a viable CD rLCMV. We observed that the degree of CD introduced in LCMV NP correlated with NP expression and functionality. Importantly, this approach allowed us to generate rLCMVs displaying different degrees of attenuation in vitro and in vivo based on their levels of CD. Unexpectedly, we could not rescue rLCMV/NPCD4 or any rLCMV containing CD sequences at the C-terminal end of LCMV NP, the reason for which remains to be determined. Whether similar levels of attenuation and protection efficacy could be achieved by CD of similar NP regions in other arenaviruses, including those causing HF disease in humans, is currently being evaluated. Nevertheless, our findings support the idea that a CD-based strategy might be effective for the development of a safe, stable, and protective live-attenuated vaccine to combat human-pathogenic arenaviruses. Moreover, this CD-based approach could be used in combination with our trisegmented arenavirus platform (47, 69, 70), which could facilitate the development of attenuated recombinant trisegmented arenaviruses expressing antigens from different human pathogens to facilitate the development of recombinant live-attenuated vaccines that could induce protection against several different human pathogens.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research in the L.M.-S. laboratory is funded by NIH grants RO1 AI077719 and R03AI099681-01A1. Research in the J.C.D.L.T. laboratory is supported by grants RO1 AI047140, RO1 AI077719, and RO1 AI079665. E.O.-R. is supported by a postdoctoral Fellowship for Diversity and Academic Excellence from the Office for Faculty Development and Diversity at the University of Rochester.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.03401-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buchmeier MJ, Peter CJ, de la Torre JC. 2007. Arenaviridae: the viruses and their replication, vol 2 Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borio L, Inglesby T, Peters CJ, Schmaljohn AL, Hughes JM, Jahrling PB, Ksiazek T, Johnson KM, Meyerhoff A, O'Toole T, Ascher MS, Bartlett J, Breman JG, Eitzen EM Jr, Hamburg M, Hauer J, Henderson DA, Johnson RT, Kwik G, Layton M, Lillibridge S, Nabel GJ, Osterholm MT, Perl TM, Russell P, Tonat K, Working Group on Civilian Biodefense . 2002. Hemorrhagic fever viruses as biological weapons: medical and public health management. JAMA 287:2391–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP. 2002. Lassa fever. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 262:75–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes GP, McCormick JB, Trock SC, Chase RA, Lewis SM, Mason CA, Hall PA, Brammer LS, Perez-Oronoz GI, McDonnell MK, Paulissen JP, Schonberger LB, Fisher-Hoch SP. 1990. Lassa fever in the United States. Investigation of a case and new guidelines for management. N Engl J Med 323:1120–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacson M. 2001. Viral hemorrhagic fever hazards for travelers in Africa. Clin Infect Dis 33:1707–1712. doi: 10.1086/322620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado S, Erickson BR, Agudo R, Blair PJ, Vallejo E, Albarino CG, Vargas J, Comer JA, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Olson JG, Nichol ST. 2008. Chapare virus, a newly discovered arenavirus isolated from a fatal hemorrhagic fever case in Bolivia. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000047. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briese T, Paweska JT, McMullan LK, Hutchison SK, Street C, Palacios G, Khristova ML, Weyer J, Swanepoel R, Egholm M, Nichol ST, Lipkin WI. 2009. Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new hemorrhagic fever-associated arenavirus from southern Africa. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000455. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer SA, Graham MB, Kuehnert MJ, Kotton CN, Srinivasan A, Marty FM, Comer JA, Guarner J, Paddock CD, DeMeo DL, Shieh WJ, Erickson BR, Bandy U, DeMaria A Jr, Davis JP, Delmonico FL, Pavlin B, Likos A, Vincent MJ, Sealy TK, Goldsmith CS, Jernigan DB, Rollin PE, Packard MM, Patel M, Rowland C, Helfand RF, Nichol ST, Fishman JA, Ksiazek T, Zaki SR, LCMV in Transplant Recipients Investigation Team . 2006. Transmission of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus by organ transplantation. N Engl J Med 354:2235–2249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palacios G, Druce J, Du L, Tran T, Birch C, Briese T, Conlan S, Quan PL, Hui J, Marshall J, Simons JF, Egholm M, Paddock CD, Shieh WJ, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Catton M, Lipkin WI. 2008. A new arenavirus in a cluster of fatal transplant-associated diseases. N Engl J Med 358:991–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schafer IJ, Miller R, Stroher U, Knust B, Nichol ST, Rollin PE. 2014. Notes from the field: a cluster of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infections transmitted through organ transplantation—Iowa, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charrel RN, de Lamballerie X. 2003. Arenaviruses other than Lassa virus. Antiviral Res 57:89–100. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilgore PE, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Mills JN, Villagra MR, Montenegro MJ, Costales MA, Paredes LC, Peters CJ. 1997. Treatment of Bolivian hemorrhagic fever with intravenous ribavirin. Clin Infect Dis 24:718–722. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levingston Macleod JM, D'Antuono A, Loureiro ME, Casabona JC, Gomez GA, Lopez N. 2011. Identification of two functional domains within the arenavirus nucleoprotein. J Virol 85:2012–2023. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01875-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKee KT Jr, Huggins JW, Trahan CJ, Mahlandt BG. 1988. Ribavirin prophylaxis and therapy for experimental Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 32:1304–1309. doi: 10.1128/AAC.32.9.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snell N. 1988. Ribavirin therapy for Lassa fever. Practitioner 232:432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maiztegui JI, McKee KT Jr, Barrera Oro JG, Harrison LH, Gibbs PH, Feuillade MR, Enria DA, Briggiler AM, Levis SC, Ambrosio AM, Halsey NA, Peters CJ. 1998. Protective efficacy of a live attenuated vaccine against Argentine hemorrhagic fever. AHF Study Group J Infect Dis 177:277–283. doi: 10.1086/514211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emonet SF, Seregin AV, Yun NE, Poussard AL, Walker AG, de la Torre JC, Paessler S. 2011. Rescue from cloned cDNAs and in vivo characterization of recombinant pathogenic Romero and live-attenuated Candid #1 strains of Junin virus, the causative agent of Argentine hemorrhagic fever disease. J Virol 85:1473–1483. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02102-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albarino CG, Bird BH, Chakrabarti AK, Dodd KA, Flint M, Bergeron E, White DM, Nichol ST. 2011. The major determinant of attenuation in mice of the Candid1 vaccine for Argentine hemorrhagic fever is located in the G2 glycoprotein transmembrane domain. J Virol 85:10404–10408. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00856-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Droniou-Bonzom ME, Reignier T, Oldenburg JE, Cox AU, Exline CM, Rathbun JY, Cannon PM. 2011. Substitutions in the glycoprotein (GP) of the Candid#1 vaccine strain of Junin virus increase dependence on human transferrin receptor 1 for entry and destabilize the metastable conformation of GP. J Virol 85:13457–13462. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05616-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contigiani M, Medeot S, Diaz G. 1993. Heterogeneity and stability characteristics of Candid 1 attenuated strain of Junin virus. Acta Virol 37:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrion R Jr, Patterson JL, Johnson C, Gonzales M, Moreira CR, Ticer A, Brasky K, Hubbard GB, Moshkoff D, Zapata J, Salvato MS, Lukashevich IS. 2007. A ML29 reassortant virus protects guinea pigs against a distantly related Nigerian strain of Lassa virus and can provide sterilizing immunity. Vaccine 25:4093–4102. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukashevich IS, Carrion R Jr, Salvato MS, Mansfield K, Brasky K, Zapata J, Cairo C, Goicochea M, Hoosien GE, Ticer A, Bryant J, Davis H, Hammamieh R, Mayda M, Jett M, Patterson J. 2008. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the ML29 reassortant vaccine for Lassa fever in small non-human primates. Vaccine 26:5246–5254. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukashevich IS, Patterson J, Carrion R, Moshkoff D, Ticer A, Zapata J, Brasky K, Geiger R, Hubbard GB, Bryant J, Salvato MS. 2005. A live attenuated vaccine for Lassa fever made by reassortment of Lassa and Mopeia viruses. J Virol 79:13934–13942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.13934-13942.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geisbert TW, Jones S, Fritz EA, Shurtleff AC, Geisbert JB, Liebscher R, Grolla A, Stroher U, Fernando L, Daddario KM, Guttieri MC, Mothe BR, Larsen T, Hensley LE, Jahrling PB, Feldmann H. 2005. Development of a new vaccine for the prevention of Lassa fever. PLoS Med 2:e183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher-Hoch SP, McCormick JB. 2004. Lassa fever vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines 3:189–197. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukashevich IS. 2012. Advanced vaccine candidates for Lassa fever. Viruses 4:2514–2557. doi: 10.3390/v4112514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikemura T. 1982. Correlation between the abundance of yeast transfer RNAs and the occurrence of the respective codons in protein genes. Differences in synonymous codon choice patterns of yeast and Escherichia coli with reference to the abundance of isoaccepting transfer RNAs. J Mol Biol 158:573–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustafsson C, Govindarajan S, Minshull J. 2004. Codon bias and heterologous protein expression. Trends Biotechnol 22:346–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andre S, Seed B, Eberle J, Schraut W, Bultmann A, Haas J. 1998. Increased immune response elicited by DNA vaccination with a synthetic gp120 sequence with optimized codon usage. J Virol 72:1497–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kane JF. 1995. Effects of rare codon clusters on high-level expression of heterologous proteins in Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol 6:494–500. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(95)80082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith DW. 1996. Problems of translating heterologous genes in expression systems: the role of tRNA. Biotechnol Prog 12:417–422. doi: 10.1021/bp950056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yadava A, Ockenhouse CF. 2003. Effect of codon optimization on expression levels of a functionally folded malaria vaccine candidate in prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression systems. Infect Immun 71:4961–4969. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.4961-4969.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikemura T. 1985. Codon usage and tRNA content in unicellular and multicellular organisms. Mol Biol Evol 2:13–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura Y, Wada K, Wada Y, Doi H, Kanaya S, Gojobori T, Ikemura T. 1996. Codon usage tabulated from the international DNA sequence databases. Nucleic Acids Res 24:214–215. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, Liu WJ, Peng SW, Sun XY, Frazer I. 1999. Papillomavirus capsid protein expression level depends on the match between codon usage and tRNA availability. J Virol 73:4972–4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burns CC, Shaw J, Campagnoli R, Jorba J, Vincent A, Quay J, Kew O. 2006. Modulation of poliovirus replicative fitness in HeLa cells by deoptimization of synonymous codon usage in the capsid region. J Virol 80:3259–3272. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3259-3272.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mueller S, Papamichail D, Coleman JR, Skiena S, Wimmer E. 2006. Reduction of the rate of poliovirus protein synthesis through large-scale codon deoptimization causes attenuation of viral virulence by lowering specific infectivity. J Virol 80:9687–9696. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00738-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang C, Skiena S, Futcher B, Mueller S, Wimmer E. 2013. Deliberate reduction of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase expression of influenza virus leads to an ultraprotective live vaccine in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:9481–9486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307473110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groseth A, Wolff S, Strecker T, Hoenen T, Becker S. 2010. Efficient budding of the Tacaribe virus matrix protein z requires the nucleoprotein. J Virol 84:3603–3611. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02429-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ortiz-Riano E, Cheng BY, de la Torre JC, Martinez-Sobrido L. 2011. The C-terminal region of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus nucleoprotein contains distinct and segregable functional domains involved in NP-Z interaction and counteraction of the type I interferon response. J Virol 85:13038–13048. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05834-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borrow P, Martinez-Sobrido L, de la Torre JC. 2010. Inhibition of the type I interferon antiviral response during arenavirus infection. Viruses 2:2443–2480. doi: 10.3390/v2112443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez-Sobrido L, Emonet S, Giannakas P, Cubitt B, Garcia-Sastre A, de la Torre JC. 2009. Identification of amino acid residues critical for the anti-interferon activity of the nucleoprotein of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol 83:11330–11340. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00763-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez-Sobrido L, Giannakas P, Cubitt B, Garcia-Sastre A, de la Torre JC. 2007. Differential inhibition of type I interferon induction by arenavirus nucleoproteins. J Virol 81:12696–12703. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00882-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinez-Sobrido L, Zuniga EI, Rosario D, Garcia-Sastre A, de la Torre JC. 2006. Inhibition of the type I interferon response by the nucleoprotein of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol 80:9192–9199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00555-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pythoud C, Rodrigo WW, Pasqual G, Rothenberger S, Martinez-Sobrido L, de la Torre JC, Kunz S. 2012. Arenavirus nucleoprotein targets interferon regulatory factor-activating kinase IKKepsilon. J Virol 86:7728–7738. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00187-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodrigo WW, Ortiz-Riano E, Pythoud C, Kunz S, de la Torre JC, Martinez-Sobrido L. 2012. Arenavirus nucleoproteins prevent activation of nuclear factor kappa B. J Virol 86:8185–8197. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07240-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng BY, Ortiz-Riano E, de la Torre JC, Martinez-Sobrido L. 1August2013. Generation of recombinant arenavirus for vaccine development in FDA-approved Vero cells. J Vis Exp doi: 10.3791/50662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flatz L, Bergthaler A, de la Torre JC, Pinschewer DD. 2006. Recovery of an arenavirus entirely from RNA polymerase I/II-driven cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:4663–4668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600652103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ortiz-Riano E, Cheng BY, Carlos de la Torre J, Martinez-Sobrido L. 2013. Arenavirus reverse genetics for vaccine development. J Gen Virol 94:1175–1188. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.051102-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basler CF, Wang X, Muhlberger E, Volchkov V, Paragas J, Klenk HD, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2000. The Ebola virus VP35 protein functions as a type I IFN antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:12289–12294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220398297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ortiz-Riano E, Cheng BY, de la Torre JC, Martinez-Sobrido L. 2012. Self-association of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus nucleoprotein is mediated by its N-terminal region and is not required for its anti-interferon function. J Virol 86:3307–3317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05503-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee KJ, Novella IS, Teng MN, Oldstone MB, de La Torre JC. 2000. NP and L proteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) are sufficient for efficient transcription and replication of LCMV genomic RNA analogs. J Virol 74:3470–3477. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.8.3470-3477.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakajima Y, Kobayashi K, Yamagishi K, Enomoto T, Ohmiya Y. 2004. cDNA cloning and characterization of a secreted luciferase from the luminous Japanese ostracod, Cypridina noctiluca. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68:565–570. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salvato M, Borrow P, Shimomaye E, Oldstone MB. 1991. Molecular basis of viral persistence: a single amino acid change in the glycoprotein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus is associated with suppression of the antiviral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response and establishment of persistence. J Virol 65:1863–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodrigo WW, de la Torre JC, Martinez-Sobrido L. 2011. Use of single-cycle infectious lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus to study hemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. J Virol 85:1684–1695. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02229-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hastie KM, Kimberlin CR, Zandonatti MA, MacRae IJ, Saphire EO. 2011. Structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein reveals a dsRNA-specific 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity essential for immune suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:2396–2401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016404108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qi X, Lan S, Wang W, Schelde LM, Dong H, Wallat GD, Ly H, Liang Y, Dong C. 2010. Cap binding and immune evasion revealed by Lassa nucleoprotein structure. Nature 468:779–783. doi: 10.1038/nature09605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hastie KM, King LB, Zandonatti MA, Saphire EO. 2012. Structural basis for the dsRNA specificity of the Lassa virus NP exonuclease. PLoS One 7:e44211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hastie KM, Liu T, Li S, King LB, Ngo N, Zandonatti MA, Woods VL Jr, de la Torre JC, Saphire EO. 2011. Crystal structure of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein-RNA complex reveals a gating mechanism for RNA binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:19365–19370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108515108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reynard S, Russier M, Fizet A, Carnec X, Baize S. 2014. Exonuclease domain of the Lassa virus nucleoprotein is critical to avoid RIG-I signaling and to inhibit the innate immune response. J Virol 88:13923–13927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01923-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karki S, Li MM, Schoggins JW, Tian S, Rice CM, MacDonald MR. 2012. Multiple interferon stimulated genes synergize with the zinc finger antiviral protein to mediate anti-alphavirus activity. PLoS One 7:e37398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Drake JW, Holland JJ. 1999. Mutation rates among RNA viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:13910–13913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin H, Lu B, Zhou H, Ma C, Zhao J, Yang CF, Kemble G, Greenberg H. 2003. Multiple amino acid residues confer temperature sensitivity to human influenza virus vaccine strains (FluMist) derived from cold-adapted A/Ann Arbor/6/60. Virology 306:18–24. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(02)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cooksley CD, Avritscher EB, Bekele BN, Rolston KV, Geraci JM, Elting LS. 2005. Epidemiology and outcomes of serious influenza-related infections in the cancer population. Cancer 104:618–628. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ljungman P, Andersson J, Aschan J, Barkholt L, Ehrnst A, Johansson M, Weiland O. 1993. Influenza A in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis 17:244–247. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muir D, Pillay D. 1998. Respiratory virus infections in immunocompromised patients. J Med Microbiol 47:561–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toback SL, Beigi R, Tennis P, Sifakis F, Calingaert B, Ambrose CS. 2012. Maternal outcomes among pregnant women receiving live attenuated influenza vaccine. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 6:44–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McKee KT Jr, Mahlandt BG, Maiztegui JI, Eddy GA, Peters CJ. 1985. Experimental Argentine hemorrhagic fever in rhesus macaques: viral strain-dependent clinical response. J Infect Dis 152:218–221. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.1.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Emonet SF, Garidou L, McGavern DB, de la Torre JC. 2009. Generation of recombinant lymphocytic choriomeningitis viruses with trisegmented genomes stably expressing two additional genes of interest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:3473–3478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900088106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Popkin DL, Teijaro JR, Lee AM, Lewicki H, Emonet S, de la Torre JC, Oldstone M. 2011. Expanded potential for recombinant trisegmented lymphocytic choriomeningitis viruses: protein production, antibody production, and in vivo assessment of biological function of genes of interest. J Virol 85:7928–7932. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00486-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.