ABSTRACT

Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus subtype H5N1 continues to be a severe threat to public health, as well as the poultry industry, because of its high lethality and antigenic drift rate. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) can serve as a useful tool for preventing, treating, and detecting H5N1. In the present study, humanized H5 antibody 8A8 was developed from a murine H5 MAb. Both the humanized and mouse MAbs presented positive activity in hemagglutination inhibition (HI), virus neutralization, and immunofluorescence assays against a wide range of H5N1 strains. Interestingly, both human and murine 8A8 antibodies were able to detect H5 in Western blot assays under reducing conditions. Further, by sequencing of escape mutants, the conformational epitope of 8A8 was found to be located within the receptor binding domain (RBD) of H5. The linear epitope of 8A8 was identified by Western blotting of overlapping fragments and substitution mutant forms of HA1. Reverse genetic H5N1 strains with individual mutations in either the conformational or the linear epitope were generated and characterized in a series of assays, including HI, postattachment, and cell-cell fusion inhibition assays. The results indicate that for 8A8, virus neutralization mediated by RBD blocking relies on the conformational epitope while binding to the linear epitope contributes to the neutralization by inhibiting membrane fusion. Taken together, the results of this study show that a novel humanized H5 MAb binds to two types of epitopes on HA, leading to virus neutralization via two mechanisms.

IMPORTANCE Recurrence of the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus subtype H5N1 in humans and poultry continues to be a serious public health concern. Preventive and therapeutic measures against influenza A viruses have received much interest in the context of global efforts to combat the current and future pandemics. Passive immune therapy is considered to be the most effective and economically prudent preventive strategy against influenza virus besides vaccination. It is important to develop a humanized neutralizing monoclonal antibody (MAb) against all of the clades of H5N1. For the first time, we report in this study that a novel humanized H5 MAb binds to two types of epitopes on HA, leading to virus neutralization via two mechanisms. These findings further deepen our understanding of influenza virus neutralization.

INTRODUCTION

Recurrence of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus subtype H5N1 in humans and poultry continues to be a serious public health concern because of its unabated and widespread geographic circulation (1). Since their emergence in Asia over a decade ago, HPAI H5N1 viruses have spread to >60 countries on three continents and are endemic in poultry in Southeast Asia and Africa (2). They have caused disease in several mammals, including humans, often with lethal consequences. To date, H5N1 has resulted in 667 human cases worldwide, including 393 deaths (3). Although no sustained human-to-human transmission of the virus has been observed so far, the concern remains that if human transmissibility were acquired, a severe pandemic could occur (4, 5).

Preventive and therapeutic measures against influenza A viruses have received much interest in the context of global efforts to combat the current pandemic and to prevent such a situation in the future. Given the emerging occurrence of oseltamivir/zanamivir-resistant viruses (6) and the high and long-term dosing requirements for antiviral drugs (7), vaccination and passive immune therapy are considered to be the most effective and economically prudent preventive strategy against influenza (8). However, vaccine strategies are usually hindered by antigenic variation (9) and cannot deliver immediate efficacy against acute infection caused by several influenza virus subtypes. These subtypes include H5N1 and H7N9 (10), which develop severe disease quickly within days of infection. The use of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) in the treatment of medical conditions has been well established for viral infectious diseases, including HIV (11) and hepatitis (12). Therefore, administration of MAbs against neutralizing epitopes may be an attractive alternative for influenza treatment (13), especially in the case of individuals who are at high risk of influenza virus infection. Such individuals include immunocompromised patients and the elderly, who do not generally respond well to active immunization (14).

Influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA), the principal determinant of immunity to the influenza virus, is the main target and antigenic source of neutralizing antibodies against viral infections (15). HA is generated as a single polypeptide and folds into a trimeric spike (HA0) that is subsequently cleaved into HA1 and HA2 subunits by host proteases during infection. The globular head domain of the HA molecule is composed of HA1 subunits and is the most immunogenic part of HA. This globular head contains the receptor binding domain, which mediates viral attachment to the host cell sialic acid receptors (16). Antibodies binding to these regions are usually strain specific, and very few cases show broad neutralization activity, even within a single subtype. HA2 and several HA1 residues form a mostly helical stem region that supports the core fusion machinery. Most stem binding antibodies have remarkably broad neutralizing activity against influenza viruses of different subtypes (17). MAbs targeting these regions are usually able to neutralize the influenza virus by physically interrupting either receptor binding or membrane fusion, two key functions of HA (18).

Humanization and human antibody production are crucial procedures in passive immune therapy since murine antibodies fail to trigger a proper human immune response and instead elicit a human anti-mouse antibody response (19, 20). However, one current challenge is that humanization often leads to loss of or changes in the effector activity of MAbs. Preserving the correct functional complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of the original murine antibodies while minimizing the murine immunogenic elements in antibodies is a critical goal in the production of human therapeutic antibodies (21).

In the present study, human H5 MAb 8A8 was generated from a neutralizing murine MAb by CDR grafting and humanized replacement in the V regions. Both human and murine MAbs presented broad neutralizing activity against different clades of H5N1 strains and showed positive reactivity to reduced H5 in Western blot assays. By epitope mapping of either escape mutants or HA fragments, different conformational and linear epitopes for the same antibody, 8A8, were identified. Neutralization mechanisms related to each type of epitope were further studied as discussed below.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production and characterization of murine MAb.

A MAb was produced as described previously. Briefly, BALB/c mice were immunized twice with a 2-week interval by the subcutaneous injection of individual binary-ethylenimine-inactivated H5N1 virus (A/Indonesia/CDC669/2006) mixed with Montanide ISA563 adjuvant (Seppic, France). Mice received an additional intravenous injection of the same viral antigen 3 days before the fusion of splenocytes with SP2/0 cells. Hybridoma culture supernatants were screened by immunofluorescence assays (IFAs). Hybridomas that produced specific MAbs were cloned by limiting dilution, expanded, and further subcultured. The hybridoma culture supernatant was clarified and tested for hemagglutination inhibition (HI) activity as described below.

Production and characterization of human MAb.

Human MAb 8A8 was generated by service collaboration with Antitope, Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom, on the basis of a murine H5 MAb. Briefly, RNA was extracted from murine 8A8 hybridoma cells with the RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion catalog no. AM1914). mRNA of the IgG heavy-chain variable region was amplified with a set of six degenerated primer pools (HA to HF), while the IgκVL light-chain V region was amplified with seven degenerate primer pools (KA to KG). PCR products were sequenced with the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega catalog no. A1360). A single functional heavy-chain variable region (VH) gene sequence and a single functional kappa light-chain variable region (Vκ) gene sequence were identified from the sequencing analysis. Structural models of the mouse 8A8 antibody V regions were produced with Swiss PDB, and the “constraining” amino acid residues in the V region that were likely to be essential in the antibody-antigen binding properties were identified. On the basis of this analysis, only a few corresponding sequence segments from human antibody sequences were identified as possible alternative residues within CDRs. VH and Vκ sequence segments of 8A8 composite human antibody variants were selected from Antitope's database of unrelated fully humanized antibodies and analyzed by iTope technology in silico (22). Sequences that were categorized as significant nonhuman germ line binders to human major histocompatibility complex class II alleles were discarded. In silico analysis with the T Cell Epitope Database (TCED) of known antibody sequence-related T cell epitopes was carried out to eliminate variants that contain potential T cell epitopes within the sequence segments and also within the junctions between the segments. Five VH sequence variants and four Vκ sequence variants were selected for humanized-antibody expression. DNA fragments encoding humanized variant VH and Vκ regions were synthesized and cloned into IgG1 expression vectors pANT17.2 and pANT13.2, respectively. The VH region was cloned by using MluI and HindIII restriction sites, and the Vκ region was cloned with BssHI and BamHI. Heavy- and light-chain recombinant constructs were stably cotransfected into NS0 cells via electroporation and selected with 200 nM methotrexate (Sigma catalog no. M8407). Expressed humanized antibody variants were screened by HI assay for the candidate with the highest yield and activity.

Viruses and cell lines.

H5N1 human influenza viruses A/Indonesia/CDC669/2006 and other viruses of clade 2.1 were obtained from the Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia. The H5N1 viruses from different phylogenetic clades or subclades were rescued by reverse genetics (RG). Briefly, the HA and neuraminidase (NA) genes of H5N1 viruses of individual clades were synthesized (GenScript) on the basis of the sequences in the NCBI influenza virus database. The synthetic HA and NA genes were cloned into a dual-promoter plasmid for influenza A virus RG (23). The dual-promoter plasmids were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Reassortant viruses were rescued by transfecting plasmids containing HA and NA along with the remaining six influenza virus genes derived from high-growth master strain A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) into cocultured 293T and MDCK cells by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corp.). At 72 h posttransfection, the culture medium was inoculated into embryonated eggs or MDCK cells. The HA and NA genes of reassortant viruses from the second passage were sequenced to confirm the presence of the introduced HA and NA genes and the absence of mutations. Stock viruses were propagated in the allantoic cavities of 10-day-old embryonated eggs, and virus-containing allantoic fluid was harvested and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Virus content was determined by a standard hemagglutination assay as described previously (24).

MDCK cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies). 293T cells were maintained in Opti-MEMI (Life Technologies) containing 5% FBS. After 48 h, the transfected-cell supernatants were collected and virus titers were determined by standard hemagglutination assays. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) of the reassortant virus was then calculated by the Reed-Muench method (25).

HI assays.

HI assays were performed as described previously (26). Briefly, MAbs or receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE)-treated sera were serially diluted (2-fold) in V-bottom 96-well plates and mixed with 4 HA units of H5 virus. Plates were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and 1% chicken red blood cells were added to each well. The HI endpoint was the highest antibody dilution in which agglutination was not observed.

Microneutralization assay.

Neutralization activity of MAb or serum against H5 strains was analyzed by microneutralization assay as previously described (27). Briefly, antibody samples were serially 2-fold diluted and incubated with 100 TCID50s of different clades of H5 strains for 1 h at room temperature and plated in duplicate onto MDCK cells grown in a 96-well plate. The neutralizing titer was assessed as the highest antibody dilution at which no cytopathic effect was observed by light microscopy.

IFA.

MDCK cells cultured in 96-well plates were infected with AIV H5 strains. At 24 h postinfection, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and washed thrice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Fixed cells were incubated with hybridoma culture supernatant at 37°C for1 h, rinsed with PBS, and then incubated with a 1:200 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse or anti-human immunoglobulin (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Cells were rinsed again in PBS, and antibody binding was evaluated by wide-field epifluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX71).

SDS-PAGE.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described previously (28), with a discontinuous buffer system and a 12% polyacrylamide separating gel. The protein samples were prepared by mixing with 2× SDS sample buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 8% SDS, 40% glycerol, 0.6 M β-mercaptoethanol, 0.05 EDTA, 0.04% bromophenol blue) and heating at 100°C for 10 min.

Western blotting.

Cell lysates of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-induced Escherichia coli cultures or H5N1 viruses were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. The proteins in the gel were then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBST (1× PBS and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with MAb supernatant, rinsed with PBST, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse or anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed with PBST, the membrane was developed by incubation with ECL reagents (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunodot blotting.

Protein samples were loaded onto a 0.45-mm nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) with a 96-well Hybri-Dot manifold (Bio-Rad). The membrane was then blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBST at room temperature for 30 min. Rinsing with PBST was done three times. The membrane was further incubated with MAbs in PBST at room temperature for 1 h. After being rinsed, the membrane was incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody conjugated with HRP for 1 h at room temperature. Bound antibodies were detected by incubation with ECL reagents (Amersham Biosciences).

Isolation and analysis of escape mutants.

The conformational epitope recognized by MAb 8A8 was mapped by characterization of escape mutants as described previously by He et al. (29). Briefly, H5N1 parental virus (A/Indonesia/CDC669/06) was incubated with an excess of MAb for 1 h and then inoculated into 11-day-old embryonated chicken eggs. The eggs were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Virus was harvested and used for cloning in limiting dilution in embryonated chicken eggs, and the escape mutants were plaque purified. The HA gene mutations were then identified by sequencing and comparison with the sequence of the parental virus.

Linear epitope mapping.

Overlapping fragments encoding the open reading frame of the HA of A/Indonesia/CDC669/06 (H5N1) (see Fig. 2A) were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pET-28a(+) vector. The peptides were expressed in E. coli and analyzed by Western blotting. A panel of mutant proteins was generated by substitution of amino acids in test positions by site-directed mutagenesis with a commercial kit (QuikChange; Stratagene), and the mutations introduced were confirmed by sequence analysis. The mutant proteins generated were further tested by Western blotting.

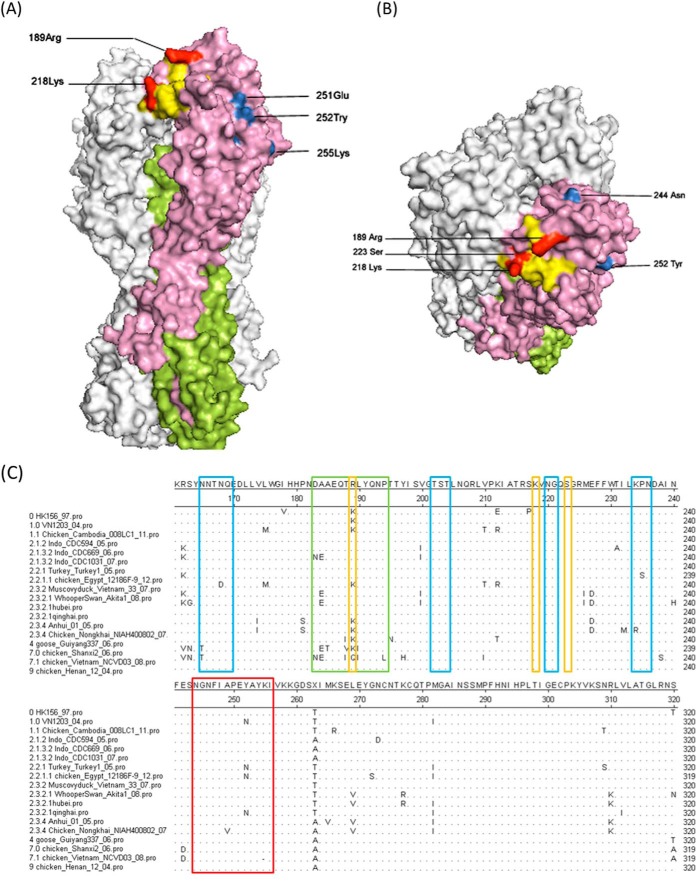

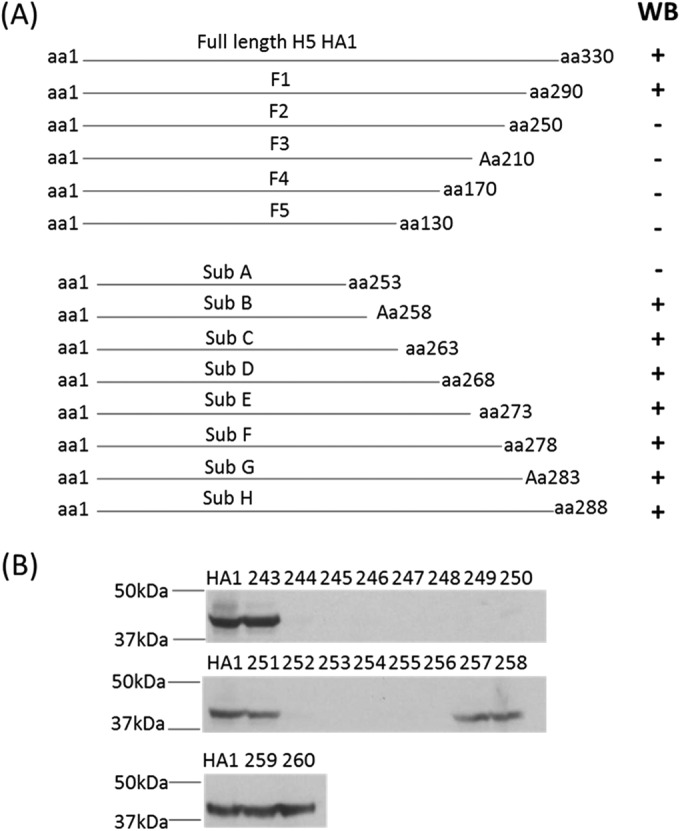

FIG 2.

Epitope mapping for h8A8. (A) Plan for epitope mapping and Western blotting (WB) results. The gene segments coding for fragments 1 to 5 and subfragments A to H were expressed as histidine-tagged proteins. The cell lysates of bacteria expressing the fragments were tested by Western blotting with h8A8 to map the epitope (the numbers of amino acids of HA1 without the signal peptide are indicated). (B) Western blotting with mutated HA1. Alanine substitutions at aa 243 to 260 of HA1 were made individually. Mutated HA1 proteins were expressed as histidine-tagged proteins. Above each lane is the amino acid position mutated in each mutant. HA1, His-tagged HA1 from wild-type CDC669.

Postattachment assay.

A 50-μl volume of a virus suspension containing 1,000 TCID50s of H5N1 was added to MDCK cells in 1 well of a 96-well plate, and then the plate was incubated at 4°C for 1 h to allow virus attachment to cells. The plate was carefully washed three times. Subsequently, 50-μl volumes of serially diluted MAbs were added to the wells and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After the plate was rinsed three times, DMEM plus 2% FBS was added at 100 μl/well; this was followed by incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h, the infection and inhibition effects were observed and determined by IFA.

Protease susceptibility assay.

The protease susceptibility assay was modified from the method described by Edwards and Dimmock (30). Briefly, H5N1 strains were incubated with antibody at 37°C for 1 h. The pH of the neutralization mixture was then either adjusted to pH 8 or lowered to pH 5 by the addition of 1 M HCl at 37°C for 45 min. The pH was then recovered to neutrality. The low-pH-induced conformational change of HA was detected by incubation with proteinase K (0.5 μg/ml; NEB) at 37°C for 30 min. The digestion was stopped by the addition of SDS loading dye and further analyzed by Western blotting.

Cell-cell fusion inhibition assay.

A cell fusion inhibition assay was performed as described previously (31). In brief, Vero cells were grown to 80% confluence in 24-well plates and transfected with plasmid pcDNA-H5 (1.6 mg of total DNA per well) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the instruction manual. Transfected cells were maintained in medium supplemented with 0.5 mg/ml G418 (iDNA). After 48 h of transfection, the culture medium was supplemented with serially diluted human IgG1 MAb 8A8 (h8A8) or a control MAb for 1 h. After being washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4), cells were incubated with low-pH fusion-inducing buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH 5.0) for 5 min and returned to the standard culture medium for 2 h at 37°C. Finally, cells were fixed with 4% polyoxymethylene and stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 20 min.

RESULTS

Humanized MAb 8A8 sustains the same reactivity to H5N1 as murine 8A8.

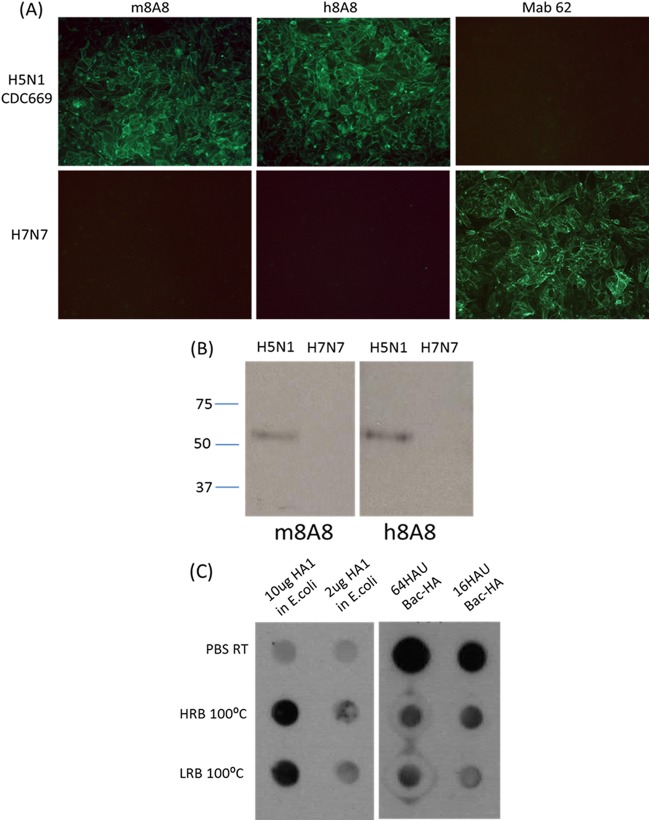

Murine MAb 8A8 (m8A8), which belongs to IgG1, revealed a pattern of cytoplasmic staining by IFA in MDCK cells infected with A/Indonesia/CDC669/06 (H5N1, CDC669). H5 specificity was verified by IFA with non-H5N1 influenza virus-infected MDCK cells. The m8A8 antibody demonstrated positive reactivity in virus neutralization, HI (Tables 1 and 2) and Western blotting assays against the whole CDC669 virus (Fig. 1A and B). The recognition spectrum was further evaluated in an HI assay with a wide range of H5N1 strains of different clades. As shown in Table 1, m8A8 was able to react to all of the H5N1 strains tested from clades 1.0 to 9 without cross-reactivity with any non-H5N1 strains, as evaluated by HI assay. On the basis of all of these significant features and in order to generate an effective reagent for human therapy, m8A8 was converted to h8A8 with minimal murine immunogenicity by CDR grafting and V region replacement. Secreted h8A8 was tested in IFA, HI, virus neutralization, and Western blotting assays for activity verification. h8A8 successfully detected H5 expression in CDC669-infected MDCK cells with no reactivity to non-H5N1 strains in an IFA. Purified h8A8 and m8A8 at equal concentrations were both able to neutralize H5N1 strains at comparable titers in both HI and virus neutralization assays (Table 2), suggesting the involvement of a conformational epitope (29). However, interestingly, both m8A8 and h8A8 were able to recognize either recombinant H5 HA1 or H5 whole virus in a Western blot assay, suggesting that 8A8 targets a linear epitope on H5.

TABLE 1.

HI titers of m8A8 against different influenza viruses

| Virus | H5 clade/subtype | HI titera |

|---|---|---|

| A/Hong Kong/156/97 | 0 | 128 |

| A/Hong Kong/213/03 | 1.0 | 256 |

| A/Vietnam/1203/04 | 1.0 | 256 |

| A/muscovy duck/Vietnam/33/07 | 1 | 128 |

| A/Indonesia/CDC594/06 | 2.1.2 | 512 |

| A/Indonesia/CDC669/06 | 2.1.3 | 512 |

| A/Indonesia/CDC1031/2007 | 2.1.3.2 | 256 |

| A/Chicken/Indonesia/TLL101/06 | 2.1 | 256 |

| A/Duck/Indonesia/TLL102/06 | 2.1 | 512 |

| A/turkey/Turkey1/05 | 2.2.1 | 256 |

| A/Nigeria/6e/07 | 2.2 | 256 |

| A/muscovy duck/Rostovon Don/51/07 | 2.2 | 128 |

| A/Jiangsu/2/07 | 2.3 | 256 |

| A/Anhui/1/05 | 2.3 | 512 |

| A/Vietnam/HN31242/07 | 2.3 | 256 |

| A/goose/Guiyang/337/06 | 4 | 128 |

| A/chicken/Shanxi/2/06 | 7 | 256 |

| A/chicken/Henan/12/04 | 9 | 128 |

| A/Puerto Rico/8/34 | H1N1 | <4 |

| A/Chicken/Malaysia/02 | H3N2 | <4 |

| A/Netherlands/219/03 | H7N7 | <4 |

| A/Chicken/Malaysia/98 | H9N2 | <4 |

The m8A8 concentration used was 500 μg/ml.

TABLE 2.

HI and virus neutralization titers of m8A8 and h8A8 against H5N1 strains of different clades

| Virus | H5 clade/subtype | HI titer with: |

VNa titer with: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m8A8b | h8A8b | m8A8 | h8A8 | ||

| A/Hong Kong/156/97 | 0 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| A/Vietnam/1203/04 | 1.0 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 256 |

| A/Indonesia/CDC594/06 | 2.1.2 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 256 |

| A/Indonesia/CDC669/06 | 2.1.3 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 256 |

| A/turkey/Turkey1/05 | 2.2.1 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 |

| A/Nigeria/6e/07 | 2.2 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| A/Jiangsu/2/07 | 2.3 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 |

| A/Anhui/1/05 | 2.3 | 128 | 128 | 256 | 256 |

| A/goose/Guiyang/337/06 | 4 | 32 | 32 | 128 | 128 |

| A/chicken/Shanxi/2/06 | 7 | 64 | 32 | 128 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Henan/12/04 | 9 | 32 | 32 | 128 | 128 |

| A/Puerto Rico/8/34 | H1N1 | <4 | <4 | <4 | <4 |

VN, virus neutralization.

Both m8A8 or h8A8 were used at 80 μg/ml.

FIG 1.

h8A8 has H5N1 binding activity similar to that of m8A8. (A) IFAs of MDCK cells infected with H5N1 (CDC669) or H7N7. Cells were fixed at 24 h postinfection, incubated with each of the primary antibodies listed, and then stained with an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. (B) Western blotting with m8A8 and h8A8 against H5N1 (CDC669) or H7N7. Each lane was loaded with 20 μl of virus at an HA titer of 25. The values to the left are molecular sizes in kilodaltons. (C) Immunodot blotting with h8A8 against native H5 or H5 in low-reduction buffer (LRB; 2% SDS) or high-reduction buffer (HRB; 0.2 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 8% SDS, 40% glycerol, 0.6 M β-mercaptoethanol, 0.05 EDTA). Two or 10 μg of E. coli-expressed H5 was loaded per dot. Sixteen or 64 hemagglutinating units (HAU) of baculovirus-expressed H5 (Bac-H5) was loaded per dot. RT, room temperature; 100°C, heated at 100°C for 10 min.

A dot blot assay with H5 under different conditions was performed to determine the reactivity of h8A8 to native and reduced H5. As shown in Fig. 1C, h8A8 could strongly detect denatured, E. coli-expressed H5 in both strongly and weakly reducing buffers after heating, but the reactivity to untreated, E. coli-expressed H5 was weak. In contrast, when probed with h8A8, strong dots were observed with native baculovirus-expressed H5 (Bac-H5), which possesses a conformation similar to that of H5 from native H5N1 (32). However, the intensity of dots with reduced Bac-H5 decreased significantly when the same blot was probed with h8A8. These observations indicate that h8A8 is able to bind either H5 in its native conformation or reduced H5 via the exposed linear epitope.

Overall, these results indicate that h8A8 preserves the properties of m8A8 binding to H5N1, as confirmed by different tests. Also, 8A8 is confirmed to be capable of binding H5 under both native and reduced conditions.

Identification of both conformational and linear epitopes for h8A8.

To discover the epitope and related binding sites for 8A8 on H5, epitope mapping was performed by two different methods. The conformational epitope was identified by using neutralization escape mutants. Taking CDC669 as the parental strain, escape mutants were generated from the selection with h8A8. Evasion was confirmed in an HI assay with h8A8 (see Table 4). The complete HA genes of the cloned escape mutants were sequenced. The HA amino acid numbering in this work is based on the numbering of H5 excluding the signal peptide. Mutant clones showed three types of mutations: double mutations at Arg189 and Ser223, a single mutation at Lys218, and a single mutation at Ser223 (Table 3). This indicated that the three amino acids are involved in the formation of the conformational epitope of 8A8.

TABLE 4.

Effects of mutations in the HA of A/Indonesia/CDC669/06 virus on the reactivity to h8A8a in HI and virus neutralization assays

| Virus | Mutation type | HI titerb |

VNc titerb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Befored | Aftere | Before | After | ||

| CDC669 | None | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| K218Q mutant | Conformational epitope | 7 | <f | 8 | < |

| S223R mutant | Conformational epitope | 7 | < | 8 | 8 |

| S223R R189K mutant | Conformational epitope | 7 | < | 8 | 8 |

| N244A mutant | Linear epitope | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| I256A mutant | Linear epitope | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

The h8A8 concentration used was 80 μg/ml.

HI and VN titers of h8A8 against the strains shown are in log2 units.

VN, virus neutralization.

Before, before mutation.

After, after mutation.

<, the titer is less than 4-fold (2 log2).

TABLE 3.

Amino acid changes in the HA of h8A8 escape mutants of parental virus A/Indonesia/CDC669/06

| Nucleotide(s) | Nucleotide change(s) | Amino acid(s) | Amino acid change(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 652 | A to C | 218 | Lys to Gln |

| 669 | T to A | 223 | Ser to Arg |

| 565, 669 | A to T, T to A | 189, 223 | Arg to Trp, Ser to Arg |

Meanwhile, the linear epitope was mapped by using a set of overlapping open reading frame expression clones and single mutant forms of recombinant H5 HA1. Fragments of H5 were designed and probed with h8A8 as shown in Fig. 2. h8A8 reacted to F1 but not to any of the rest (F2 to F5), indicating that the epitope comprised amino acids from amino acid (aa) 250 to aa 290. Subfragments A to H were further generated to refine the epitope and revealed that h8A8 targets amino acids upstream of aa 258. A panel of HA1 proteins with single substitutions from aa 243 to aa 260 were subsequently constructed, expressed, and analyzed by Western blotting with h8A8. The results showed that h8A8 failed to react with individual HA1 proteins carrying single amino acid substitutions from aa 244 to aa 256, with the exception of the E251A mutant protein. Two mutations at the same position, E251R and E251W, were further found to be positive in Western blotting with h8A8, suggesting that the contribution of aa 251 to H5 recognition by h8A8 is minor. Taken together, these findings indicate that the linear epitope of h8A8 ranges from aa 244 to aa 256.

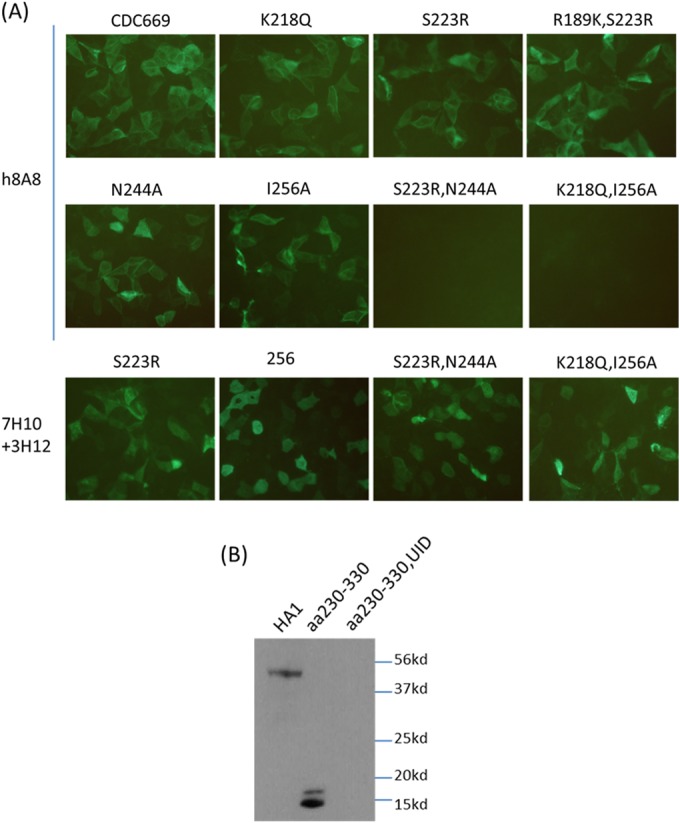

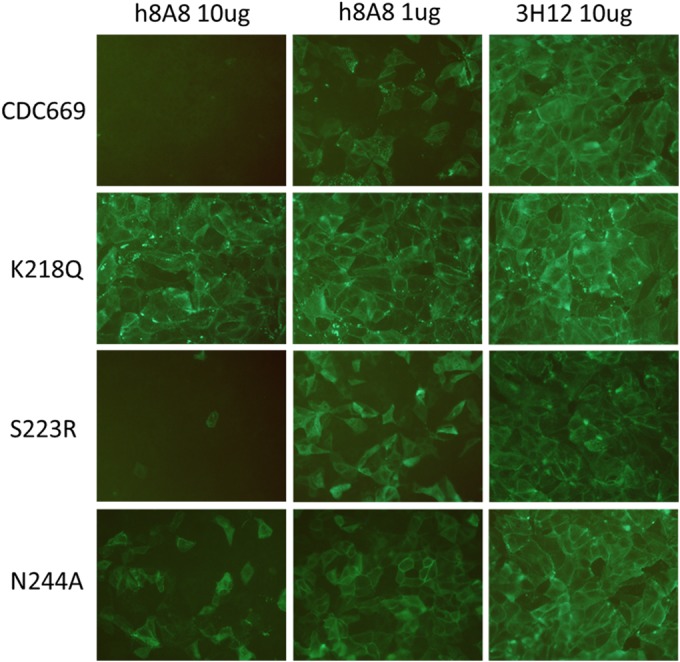

The two types of h8A8 epitopes are independent of each other.

Vero cells were transfected with constructs expressing H5 proteins with individual mutated epitopes. HA expression was probed with either h8A8 or control H5 antibodies targeting the N terminus of H5. As shown by IFA (Fig. 3A), h8A8 detected H5 expression in Vero cells transfected individually with these epitope mutant constructs, with the exception of the double mutant constructs in both types of epitopes. In IFA, both native and denatured HAs are present together in cells. Hence, this result indicates that any disruption in one type of epitope does not largely affect h8A8 recognizing the other type. Binding is abolished only when both epitopes are mutated.

FIG 3.

Independent binding to the two types of epitopes by h8A8. (A) Reactivity of h8A8 to a range of epitope mutants in an IFA. IFAs with Vero cells transfected with epitope mutants were performed with h8A8 and other H5 antibodies. 7H10 and 3H12 were mixed together as positive controls. (B) Western blot assay with h8A8 against an HA1 peptide fragment excluding the conformational epitope (aa 230 to 330). HA1, full-length HA1 of CDC669; UID, preinduction sample used as a negative control.

To confirm the independent binding of the two epitopes, a peptide fragment expressing the linear epitope only was designed and probed with h8A8 as shown in Fig. 3B. In a Western blot assay, h8A8 successfully detected the fragment (aa 230 to 330) in which the conformational epitope was completely excluded. With the same protein quantity, the signal density of the fragment band was similar to that of the full-length HA1 band in the blot assay probed with h8A8. Therefore, the result confirmed that the interaction of h8A8 with the linear epitope is independent of the conformational epitope.

The three-dimensional structure of CDC669 H5 was generated by Swiss-Model. Amino acid positions involved in the formation of either the conformational or the linear epitope are highlighted in the HA structure in Fig. 4A and B. Amino acids 218 and 223 from the conformational epitope are both located in 220-loop. Together with aa 189, the three amino acids are found within the receptor binding domain (RBD) of H5 (33). Further, aa 189 is located at antigenic site Sb (34). In contrast, none of the amino acids from the linear epitope are located in the RBD or any antigenic site. The whole linear epitope is not exposed in the structure of mature HA. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, the central part of the linear epitope was internalized behind other amino acids. This observation suggests that the interactions of h8A8 with the two types of epitopes do not occur simultaneously. Therefore, the results further confirm that the conformational and linear epitopes of h8A8 are independent of each other.

FIG 4.

Epitope location and sequence analysis. Side (A) and top (B) views of the structure of CDC669 H5 are shown. HA1 (aa 1 to 330) is pink, and HA2 is green. The other two monomers are white. The RBD is yellow. The conformational epitope (aa 218, 223, and 189) is red while the linear epitope (aa 244 to 256) is blue. The conformational epitope overlaps the RBD. The structure was generated by Swiss-Model (http://beta.swissmodel.expasy.org) (44–46), and the diagrams were generated by the PyMOL program (http://www.pymol.org/). (C) Identification of epitopes in antigenic sites among different clades. H5 protein sequences of different major clades were aligned. Amino acid consensus sequences of H5N1 HA clades are highlighted at positions equivalent to the H1 antigenic sites, Ca (in blue boxes) and Sb (in green boxes). The linear epitope is in the red box, and the conformational-epitope-related amino acids are in yellow boxes.

To study the conservation of the epitopes, an alignment of H5 protein sequences of different clades was performed (Fig. 4C). Amino acids 218 and 223, the two residues whose individual mutation caused virus evasion, were found to be conserved among different major clades, while position aa 189 of the double escape mutant tended to be variable. The 13-aa linear epitope was generally conserved among these clades, with sporadic variations at two positions, aa 249 and 252.

The conformational epitope of 8A8 is responsible for receptor binding.

Because the amino acids of the conformational epitope are found within antigenic sites and the RBD, it is believed that the antibody binding the conformational epitope should inhibit virus attachment to host cells. To further characterize the epitopes identified, a panel of RG influenza viruses based on CDC669 H5 was generated with individual mutations covering various amino acids from the two epitopes. HI assays and virus neutralization were thus performed with h8A8 and the panel of RG mutants with changes in the epitopes identified (Table 4). The h8A8 antibody failed to inhibit the hemagglutination of three RG mutants, which were generated according to escape mutants (R189K S223R, K218Q, and S223R) but successfully stopped the hemagglutination of mutants with changes in the linear epitope (N244A and I256A). Similarly, in virus neutralization assays, h8A8 neutralized the mutants with changes in the linear epitope but not RG escape mutant K218Q. Interestingly, however, h8A8 fully neutralized the S223R and R189K S223R mutants, which were not reactive to h8A8 in an HI assay, suggesting that other neutralization machinery is employed. Taken together, the results confirm that the conformational epitope identified for h8A8 is responsible for receptor binding and that h8A8 blocks the RBD by binding to the conformational epitope, leading to virus neutralization. Also, the results imply that h8A8 uses a neutralization mechanism that does not depend on RBD blocking and is independent of the conformational epitope.

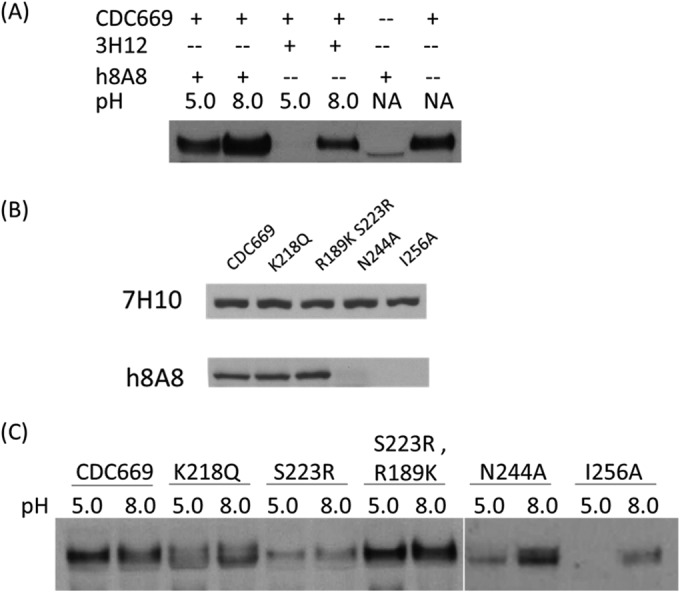

The linear epitope of 8A8 is involved in member fusion.

In order to identify other neutralization mechanisms of h8A8, a postattachment assay was first performed with h8A8 against CDC669 and the panel of RG mutants with changes in the epitopes (Fig. 5). With the incubation of h8A8 in MDCK cells after virus attachment, infection of CDC669 was completely inhibited at a dose of 10 μg and partially inhibited with 1 μg of h8A8. The K218Q mutant escaped from this postattachment neutralization, consistent with its escape from neutralization discussed earlier. The other conformational epitope mutant, the S223R mutant, showed inhibition similar to that of wild-type CDC669, indicating that aa 223 of the conformation epitope is not involved in postattachment neutralization. In contrast, the high dose of h8A8 failed to abolish the infection of the linear-epitope mutant (the N244A mutant) and only a slight decrease in infection was observed with the low dose of h8A8, indicating that the linear epitope contributes to postattachment neutralization by h8A8.

FIG 5.

Postattachment neutralization assays with h8A8 and MDCK cells. 3H12 is an HI antibody against H5N1 that was used as a control. Wild-type CDC669 and RG H5N1 strains with individual mutations in either the conformational or the linear epitope were tested. Infection was visualized by immunofluorescence staining with MAb 7H10.

Because inhibition in membrane fusion is the major mechanism of postattachment neutralization, protease susceptibility and cell-cell fusion inhibition assays were further performed. In the protease susceptibility assay, the H5 protein was exposed to a low pH (5.0) to trigger pH-induced conformational changes and susceptibility to degradation by protease K. As shown in Fig. 6A, when incubated with 3H12, a control antibody with HI activity, CDC669 H5 was detected in the sample at pH 8.0 but not at pH 5.0. In contrast, upon preincubation with h8A8 before exposure to pH 5.0, the degradation of CDC669 H5 was inhibited. Before the protease assay, CDC669 and RG epitope mutants were first tested by Western blotting with h8A8 (Fig. 6B). h8A8 is able to detect the conformational epitope mutants, as well as wild-type CDC669. In contrast, no band was observed in any of the linear-epitope mutants probed by h8A8. h8A8 was further incubated with a range of epitope mutants for the degradation susceptibility study (Fig. 6C). Each mutant was tested at the same HA titer of 26. Significant degradation of H5 upon low-pH treatment was observed in the N244A and I256A linear-epitope mutants, whereas conformational-epitope mutants treated with low pH were detected at a density similar to that of the groups treated with pH 8.0. These observations indicate that h8A8 binding is able to protect H5 from degradation at low pH and that this protection is mediated by interaction with the linear epitope. This is the key indicator of membrane fusion inhibition (35).

FIG 6.

Protease susceptibility assays with H5 and h8A8. H5 was visualized in Western blotting with MAb 7H10, an antibody targeting the N terminus of H5. (A) h8A8 was able to protect H5 (CDC669) from low-pH-mediated degradation by protease K. 3H12 is an HI antibody against H5N1 that was used as a control. NA, no pH adjustment and no protease treatment. (B) Western blotting of epitope mutants with h8A8. 7H10 is a control MAb against the N terminus of H5. Each lane was loaded with 20 μl of virus at an HA titer of 28. (C) RG H5N1 strains with individual mutations in either the conformational or the linear epitope were tested in protease susceptibility assays with h8A8.

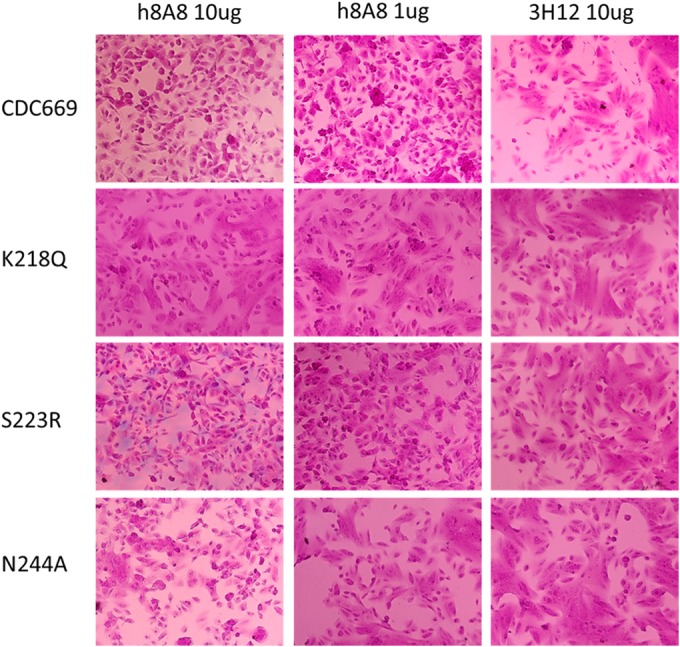

In the cell-cell fusion inhibition assay (Fig. 7), h8A8 at both high and low doses successfully inhibited the cell-cell fusion caused by an H5 conformation change upon exposure to a low pH, while control antibody 3H12 failed to stop fusion. The K218Q complete-escape mutant did not shown any interference of either h8A8 or 3H12 with fusion. Fusion by the S223R conformational-epitope mutant was significantly inhibited by h8A8 but not by 3H12. H8A8 partially reduced the fusion caused by linear-epitope N244A mutant H5, even at the high dose. Taken together, these results confirm that h8A8 is able to disturb HA-mediated membrane fusion and also that the linear epitope is involved in this inhibition.

FIG 7.

Inhibition of cell-cell fusion of H5-transfected Vero cells by h8A8. 3H12 is an HI antibody against H5N1 that was used as a control. Wild-type CDC669 and RG H5N1 strains with individual mutations in either the conformational or the linear epitope were tested.

DISCUSSION

As is the case with the majority of neutralizing antibodies, HA serves as the most important target in passive immune therapy, as well as in the development of vaccines against HPAI viruses such as H5N1 (36). RBD blocking by head-binding MAbs is one of the mechanisms employed most by antibodies for influenza virus neutralization. Three other mechanisms have been characterized for HA-targeted neutralization, including inhibition of membrane fusion, HA cleavage, and virus egress (37). In this study, a unique MAb was found to react with two types of epitopes on HA and to neutralize H5N1 via two different mechanisms. This humanized antibody has the same immunological activity and neutralizing features as the original murine antibody, providing a useful tool for effective and efficient antibody therapy against H5N1.

On the basis of the results, it is believed that the functions of two epitopes targeted by 8A8 are independent of each other, instead of being synergistic in neutralization. First, the two epitopes do not exist simultaneously in one HA subunit. The conformational epitope appears only in the native HA structure at the time when the linear epitope is shielded by other amino acids on the surface. The linear epitope is exposed when the HA conformation changes by either natural processes or environmental factors. Certain biological processes leading to changes in HA structure include membrane fusion by low pH and potential virus “breath.” Studies with enveloped virus suggest that mature virions are dynamically “breathing” (38), a reference to regular motions among amino acids in enveloped proteins. Since the influenza virus is enveloped, similar dynamics could occur in glycoproteins present on the viral surface. When the exposed linear epitope is bound by MAbs, the related biological process will be disrupted, leading to virus neutralization. Environmental factors such as heat or chemical contact will also denature HA and expose the linear epitope (39). Therefore, 8A8 is able to efficiently recognize H5 from samples under different conditions, making it a useful detection antibody. Further, mutations in the linear epitope do not affect RBD-mediated neutralization, as indicated by HI, confirming that the linear epitope plays no role in head blocking by 8A8. Similarly, mutations in the conformational epitope do not abolish 8A8 reactivity to HA in a Western blot assay, showing that the interaction with denatured HA does not rely on the conformational epitope at all. Taking the results together, it is concluded that 8A8 binds to two different types of epitopes, respectively, under different conditions.

The two types of epitopes that act individually lead to the same virus neutralization efficacy but via two separate mechanisms. As identified in escape mutants and confirmed by HI evasion, the conformational epitope is linked to RBD-mediated neutralization. Further, H5 structure studies indicate that the amino acids identified by escape mutants are located within the RBD. This confirms that 8A8 binding blocks the RBD and inhibits virus attachment to cells, leading to virus neutralization. The R189K S223R and S223R escape mutants were initially selected on the basis of 8A8 evasion in an HI assay. Interestingly, h8A8 failed to react with the R189K S223R and S223R mutants in the HI test but succeeded in neutralizing both in MDCK cells, suggesting that other machinery is involved in 8A8-induced virus neutralization. One way in which the influenza virus is neutralized could be interference with the low-pH-induced conformational change in the HA molecule, resulting in inhibition of fusion during viral replication (40). A few neutralizing antibodies have been reported to employ this strategy, most of which target epitopes in either the C terminus of HA1 or the N terminus of HA2. As shown in a previous study by Tan's group (41), MAb 9F4 was able to neutralize H5 by inhibiting membrane fusion. 9F4 recognizes the IVKK epitope at aa 256 to 259. The epitope is next to the linear epitope identified here, with one amino acid overlapping, implying that the linear epitope of 8A8 is involved in the same mechanism. The protease susceptibility assay demonstrated that 8A8 could prevent HA degradation caused by a low pH and that this function relies on the linear epitope being intact. The cell-cell fusion inhibition assay corroborates the theory that h8A8 inhibits membrane fusion and indicates that the linear-epitope mutant is less responsive to inhibition than wild-type CDC669 is. However, no reduction of the neutralization titer of h8A8 against the linear-epitope mutants was observed, suggesting that the role of the linear epitope in total neutralization is minor compared to that of RBD-mediated neutralization. Therefore, it is concluded that 8A8 interaction with the conformational epitope is responsible for blocking RBD and that binding of the linear epitope leads to inhibition of membrane fusion.

8A8 has broad neutralization activity and recognition of H5 from different clades, which relies on these conserved epitopes. Amino acids in RBD are usually not conserved because of antigenic drift (42). However, the two amino acids identified in the 218K and 223S single escape mutants are highly stable among different clades of H5N1 strains even though they are within the RBD. This may be caused by a possible deficiency in the infectivity or replication of these escape mutants. As noticed in an IFA with infected MDCK cells (data not shown), weaker H5 expression by S223R infection was detected with both 8A8 and control H5 MAbs than the expression by wild-type CDC669, suggesting that the mutation in 223R may not be selected for among H5N1 strains. Because the conformational and linear epitopes are independent, the linear epitope serves as an additional binding site for 8A8, thus extending the recognition spectrum of 8A8. The linear epitope is conserved among most clades with sporadic variations in only 2 aa. Some mutations are compatible with 8A8 binding, such as those at 251E. Therefore, on the basis of the two types of conserved epitopes, 8A8 is able to neutralize and recognize a wide range of H5N1 strains in all of the major clades.

In order to minimize murine immunogenicity in a MAb, humanization is a required step for passive immune therapy. However, the original activity of murine antibodies, including neutralizing efficacy, may be altered during the humanization steps. In this study, CDR grafting and substitution of murine T cell epitopes (43) were performed for complete humanization of MAb 8A8. The reactivity of h8A8 to H5N1 is comparable to that of m8A8, as evaluated by IFA, Western blotting, HI, and virus neutralization. Hence, humanization on the basis of a fine substitution of murine antigenic residues with TCED (22) was found to be successful without any disturbance of H5 binding affinity. Therefore, h8A8 can serve as a safe and effective therapeutic agent for the treatment of humans with potentially lethal H5N1 infections.

In summary, this study shows that h8A8 is a fully humanized antibody with strong neutralization activity and broad cross-clade protection against H5N1. These advantages of h8A8 come from the dual recognition of two different types of epitopes that cause virus neutralization via two different mechanisms. The is the first report, to our knowledge, showing that an H5 antibody is able to bind two types of epitopes for neutralization by using different mechanisms and increases our understanding of HA-mediated neutralization among influenza viruses. Besides passive therapeutics and prophylactics, 8A8 can also be used for sensitive and specific detection of H5N1 strains of various clades. The linear and conformational epitopes allow 8A8 to detect H5N1 in different forms and under different conditions, including native and denatured samples. In the next study, efforts will be made to further characterize the antiviral and diagnostic functions of 8A8 at the preclinical level.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, Singapore.

We are very thankful to J. Sivaraman and K. Swaminathan of the National University of Singapore and Xiaowei Li of Xiamen University, China, for their advice. We are very thankful to Ian Cheong from the Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, Singapore, for proofreading the manuscript.

We have no conflicts interest to declare.

F.H. and J.K. conceived and designed the experiments; Y.R.T., Q.Y.N., F.H., and Q.J. performed the experiments; F.H. and J.K. analyzed the data; and F.H. wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Jong MD, Hien TT. 2006. Avian influenza A (H5N1). J Clin Virol 35:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris JS, de Jong MD, Guan Y. 2007. Avian influenza virus (H5N1): a threat to human health. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:243–267. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00037-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. 27July2014, posting date Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2014. http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/EN_GIP_20140727CumulativeNumberH5N1cases.pdf WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan Y, Poon LL, Cheung CY, Ellis TM, Lim W, Lipatov AS, Chan KH, Sturm-Ramirez KM, Cheung CL, Leung YH, Yuen KY, Webster RG, Peiris JS. 2004. H5N1 influenza: a protean pandemic threat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:8156–8161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402443101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Das SC, Ozawa M, Shinya K, Zhong G, Hanson A, Katsura H, Watanabe S, Li C, Kawakami E, Yamada S, Kiso M, Suzuki Y, Maher EA, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. 2012. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature 486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le QM, Kiso M, Someya K, Sakai YT, Nguyen TH, Nguyen KH, Pham ND, Ngyen HH, Yamada S, Muramoto Y, Horimoto T, Takada A, Goto H, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Kawaoka Y. 2005. Avian flu: isolation of drug-resistant H5N1 virus. Nature 437:1108. doi: 10.1038/4371108a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yen HL, Monto AS, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. 2005. Virulence may determine the necessary duration and dosage of oseltamivir treatment for highly pathogenic A/Vietnam/1203/04 influenza virus in mice. J Infect Dis 192:665–672. doi: 10.1086/432008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baz M, Luke CJ, Cheng X, Jin H, Subbarao K. 2013. H5N1 vaccines in humans. Virus Res 178:78–98. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pica N, Palese P. 2013. Toward a universal influenza virus vaccine: prospects and challenges. Annu Rev Med 64:189–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-120611-145115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He F, Kumar SR, Syed Khader SM, Tan Y, Prabakaran M, Kwang J. 2013. Effective intranasal therapeutics and prophylactics with monoclonal antibody against lethal infection of H7N7 influenza virus. Antiviral Res 100:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu W, Hofmann-Lehmann R, McClure HM, Ruprecht RM. 2002. Passive immunization with human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies: correlates of protective immunity against HIV. Vaccine 20:1956–1960. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao J, Meng S, Li C, Ji Y, Meng Q, Zhang Q, Liu F, Li J, Bi S, Li D, Liang M. 2008. Efficient neutralizing activity of cocktailed recombinant human antibodies against hepatitis A virus infection in vitro and in vivo. J Med Virol 80:1171–1180. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng W, Pan W, Zhang AJ, Li Z, Wei G, Feng L, Dong Z, Li C, Hu X, Sun C, Luo Q, Yuen KY, Zhong N, Chen L. 2013. Rapid generation of human-like neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in urgent preparedness for influenza pandemics and virulent infectious diseases. PLoS One 8:e66276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laursen NS, Wilson IA. 2013. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against influenza viruses. Antiviral Res 98:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. 2010. Influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase membrane glycoproteins. J Biol Chem 285:28403–28409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.129809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisen MB, Sabesan S, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 1997. Binding of the influenza A virus to cell-surface receptors: structures of five hemagglutinin-sialyloligosaccharide complexes determined by X-ray crystallography. Virology 232:19–31. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krammer F, Palese P. 2013. Influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based antibodies and vaccines. Curr Opin Virol 3:521–530. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem 69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huston JS, George AJ. 2001. Engineered antibodies take center stage. Hum Antibodies 10:127–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marasco WA, Sui J. 2007. The growth and potential of human antiviral monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol 25:1421–1434. doi: 10.1038/nbt1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong F, Xia L, Wang J, Wu B, Wang D, Yuan L, Cheng Y, Zhu H, Che X, Zhang Q, Zhao G, Wang Y. 2014. A high-affinity CDR-grafted antibody against influenza A H5N1 viruses recognizes a conserved epitope of H5 hemagglutinin. PLoS One 9:e88777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry LC, Jones TD, Baker MP. 2008. New approaches to prediction of immune responses to therapeutic proteins during preclinical development. Drugs R D 9:385–396. doi: 10.2165/0126839-200809060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prabakaran M, Ho HT, Prabhu N, Velumani S, Szyporta M, He F, Chan KP, Chen LM, Matsuoka Y, Donis RO, Kwang J. 2009. Development of epitope-blocking ELISA for universal detection of antibodies to human H5N1 influenza viruses. PLoS One 4:e4566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He F, Ho Y, Yu L, Kwang J. 2008. WSSV ie1 promoter is more efficient than CMV promoter to express H5 hemagglutinin from influenza virus in baculovirus as a chicken vaccine. BMC Microbiol 8:238. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg 27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prabhu N, Prabakaran M, Hongliang Q, He F, Ho HT, Qiang J, Goutama M, Lim AP, Hanson BJ, Kwang J. 2009. Prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of a chimeric monoclonal antibody specific for H5 haemagglutinin against lethal H5N1 influenza. Antivir Ther 14:911–921. doi: 10.3851/IMP1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He F, Kwang J. 2013. Monoclonal antibody targeting neutralizing epitope on H5N1 influenza virus of clade 1 and 0 for specific H5 quantification. Influenza Res Treat 2013:360675. doi: 10.1155/2013/360675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K (ed). 1999. 1999 Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prabakaran M, He F, Meng T, Madhan S, Yunrui T, Jia Q, Kwang J. 2010. Neutralizing epitopes of influenza virus hemagglutinin: target for the development of a universal vaccine against H5N1 lineages. J Virol 84:11822–11830. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00891-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edwards MJ, Dimmock NJ. 2001. Hemagglutinin 1-specific immunoglobulin G and Fab molecules mediate postattachment neutralization of influenza A virus by inhibition of an early fusion event. J Virol 75:10208–10218. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10208-10218.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Z, Meng J, Li X, Wu R, Huang Y, He Y. 2012. The epitope and neutralization mechanism of AVFluIgG01, a broad-reactive human monoclonal antibody against H5N1 influenza virus. PLoS One 7:e38126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He F, Madhan S, Kwang J. 2009. Baculovirus vector as a delivery vehicle for influenza vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 8:455–467. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens J, Blixt O, Tumpey TM, Taubenberger JK, Paulson JC, Wilson IA. 2006. Structure and receptor specificity of the hemagglutinin from an H5N1 influenza virus. Science 312:404–410. doi: 10.1126/science.1124513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He F, Prabakaran M, Rajesh Kumar S, Tan Y, Kwang J. 2014. Monovalent H5 vaccine based on epitope-chimeric HA provides broad cross-clade protection against variant H5N1 viruses in mice. Antiviral Res 105:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ekiert DC, Bhabha G, Elsliger MA, Friesen RH, Jongeneelen M, Throsby M, Goudsmit J, Wilson IA. 2009. Antibody recognition of a highly conserved influenza virus epitope. Science 324:246–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1171491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekiert DC, Wilson IA. 2012. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against influenza virus and prospects for universal therapies. Curr Opin Virol 2:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandenburg B, Koudstaal W, Goudsmit J, Klaren V, Tang C, Bujny MV, Korse HJ, Kwaks T, Otterstrom JJ, Juraszek J, van Oijen AM, Vogels R, Friesen RH. 2013. Mechanisms of hemagglutinin targeted influenza virus neutralization. PLoS One 8:e80034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowd KA, Mukherjee S, Kuhn RJ, Pierson TC. 2014. Combined effects of the structural heterogeneity and dynamics of flaviviruses on antibody recognition. J Virol 88:11726–11737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01140-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He F, Du Q, Ho Y, Kwang J. 2009. Immunohistochemical detection of Influenza virus infection in formalin-fixed tissues with anti-H5 monoclonal antibody recognizing FFWTILKP. J Virol Methods 155:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bullough PA, Hughson FM, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 1994. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature 371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh HL, Akerstrom S, Shen S, Bereczky S, Karlberg H, Klingstrom J, Lal SK, Mirazimi A, Tan YJ. 2010. An antibody against a novel and conserved epitope in the hemagglutinin 1 subunit neutralizes numerous H5N1 influenza viruses. J Virol 84:8275–8286. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02593-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koel BF, Burke DF, Bestebroer TM, van der Vliet S, Zondag GC, Vervaet G, Skepner E, Lewis NS, Spronken MI, Russell CA, Eropkin MY, Hurt AC, Barr IG, de Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA, Smith DJ. 2013. Substitutions near the receptor binding site determine major antigenic change during influenza virus evolution. Science 342:976–979. doi: 10.1126/science.1244730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryson CJ, Jones TD, Baker MP. 2010. Prediction of immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins: validity of computational tools. BioDrugs 24:1–8. doi: 10.2165/11318560-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guex N, Peitsch MC, Schwede T. 2009. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis 30(Suppl 1):S162–S173. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiefer F, Arnold K, Kunzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. 2009. The SWISS-MODEL repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D387–D392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]