Abstract

Algae are important primary colonizers of snow and glacial ice, but hitherto little is known about their ecology on Iceland's glaciers and ice caps. Due do the close proximity of active volcanoes delivering large amounts of ash and dust, they are special ecosystems. This study provides the first investigation of the presence and diversity of microbial communities on all major Icelandic glaciers and ice caps over a 3 year period. Using high-throughput sequencing of the small subunit ribosomal RNA genes (16S and 18S), we assessed the snow community structure and complemented these analyses with a comprehensive suite of physical-, geo-, and biochemical characterizations of the aqueous and solid components contained in snow and ice samples. Our data reveal that a limited number of snow algal taxa (Chloromonas polyptera, Raphidonema sempervirens and two uncultured Chlamydomonadaceae) support a rich community comprising of other micro-eukaryotes, bacteria and archaea. Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes were the dominant bacterial phyla. Archaea were also detected in sites where snow algae dominated and they mainly belong to the Nitrososphaerales, which are known as important ammonia oxidizers. Multivariate analyses indicated no relationships between nutrient data and microbial community structure. However, the aqueous geochemical simulations suggest that the microbial communities were not nutrient limited because of the equilibrium of snow with the nutrient-rich and fast dissolving volcanic ash. Increasing algal secondary carotenoid contents in the last stages of the melt seasons have previously been associated with a decrease in surface albedo, which in turn could potentially have an impact on the melt rates of Icelandic glaciers.

Keywords: snow algae, Iceland, glaciers, microbial diversity, bacteria, archaea, sequencing, albedo

Introduction

Glaciers and ice sheets cover about 10% of the Earth's surface and are the largest freshwater reservoir. They are a critical component of the Earth's climate system and with temperatures rising globally, melting rates are increasing affecting freshwater availability and sea level rise (Meier et al., 2007). Glacial surfaces have not been considered to harbor much life until recently (Hodson et al., 2008; Anesio and Laybourn-Parry, 2012). They are considered an extreme environment yet they contain species of all three domains of life including bacteria, archaea, fungi, protozoa, and even invertebrates (Anesio and Laybourn-Parry, 2012). Among glacial surface habitats, cryoconite holes (cyanobacteria dominated water-filled holes formed by the preferential melt of organic and inorganic dark particles) have been by far the more extensively studied habitats (Cameron et al., 2012; Edwards et al., 2014). However, the largest proportion (>90%) of glacial surfaces is covered by snow and increasingly by bare ice toward the end of the melting season. Snow algae (Chlorophyta) are the most prolific and colorfully striking microbial species colonizing snow and ice surfaces. First described by the ancient Greek Aristotle (Gentz-Werner, 2007), snow algae have been known for a long time and they have been studied in many polar and alpine cryospheric settings including Greenland (Lutz et al., 2014), Svalbard (Müller et al., 2001; Leya et al., 2004), the European Alps (Remias et al., 2005), the Rocky Mountains (Thomas and Duval, 1995), Antarctica (Fujii et al., 2010; Remias et al., 2013), Alaska (Takeuchi, 2013) and the Himalayans (Yoshimura et al., 2006). We have recently shown that they are important primary colonizers and net primary producers supporting other snow and ice microbial communities as carbon and nutrient sources (Lutz et al., 2014). As part of their life cycle and as a mechanism of protection from high irradiation, snow algal species produce red pigments (carotenoids). Through this protective reaction, algal blooms color snow and ice surfaces and cause a darkening of glacial surfaces which in turn leads to a decrease in surface albedo (Thomas and Duval, 1995; Yallop et al., 2012; Takeuchi, 2013; Benning et al., 2014; Lutz et al., 2014). Such a decrease of albedo may speed up melting processes even further. This is of special interest in Iceland where glaciers have been shown to be retreating very fast (Staines et al., 2014) and where albedo is also affected by the presence of volcanic dust and ash on snow and ice surfaces.

Currently, not a single description of snow algae from any of the glaciers or ice caps in Iceland is available in the literature and no Icelandic snow algal species are available in cryogenic culture collections. Thus, we do not know if they are present, and if so, if they are abundant or what their bio-geographical distribution or ecological role might be. This is despite the fact that anecdotal evidence from scientists working on Iceland's glaciers and ice caps (e.g., personal communication from Glaciology Prof. Magnús Tumi Guðmundsson, University of Iceland) suggests that occasionally in the late summer “reddish snow” patches can be observed. Icelandic glaciers represent a special case of glacial ecosystems due to their vicinity to active volcanoes and thus constant input of fresh ash through dust or eruptions. The very abundant dark ash that covers most snow and ice fields on Iceland's glaciers and ice caps in the summer melting season is most likely also the reason why so far colored snow algae have not been described. The darkness of volcanic ash contributes to the darkening of Icelandic glacial surfaces and their faster melting (Guðmundsson et al., 2005; Möller et al., 2014). Possibly, this effect also extends the active growth season of snow algae due to earlier and prolonged availability of liquid water. The highly soluble volcanic ash (Ritter, 2007; Jones and Gislason, 2008) is an important source of essential nutrients (e.g., N, P, Fe) and thus could be a good substrate for snow algal growth, which may further enhance the negative effect on surface albedo.

With this study we aimed to identify the presence of snow and ice algae on Icelandic glacial surfaces. Furthermore, we wanted to detail their associated microbial communities, and finally place the communities on all major Icelandic glaciers and ice caps in the context of variations in biogeography and physico–chemical parameters of snow and ice.

Materials and methods

Field site, sampling, and measurements

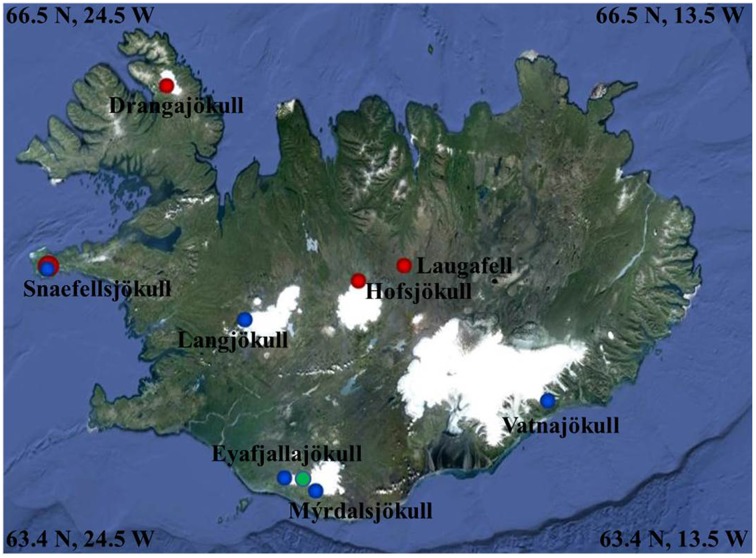

A total of 33 snow and 1 ice samples (labeled with “ICE” for Iceland, followed by the collection year and sample number: ICE-12_1–7, ICE-13_1–24 and ICE-14_1–3; Table 1) was collected from seven glaciers and one ice cap in Iceland (see Figure 1 and Table 1 for details). Snow fields in the terminus areas of the western glacier Snaefellsjökull, the northern glacier Drangajökull, the central glacier Hofsjökull, as well as a large permanent snow field near Laugafell in the Central Highlands were sampled at the end of July in 2012. In early June 2013 we sampled the terminus areas of the southern glaciers Vatnajökull, Eyafjallajökull, Mýrdalsjökull, and Solheimajökull and the western glaciers Snaefellsjökull and Langjökull. Finally, we sampled three snow fields that covered fresh lava fields from the 2010 eruption of Eyafjallajökull at the end of August in 2014 in order to also assess how and if fresh microbial colonization had occurred. It is worth noting that in 2012 and 2014 melting had been very advanced leading to thin snow covers on the termini of all glaciers and smaller permanent snow fields. However, microbial colonization was well-developed at all sites. In contrast, the samples in 2013 were collected in early June, when melting had just been initiated and thick snow packs were still present at all sites and microbial colonization was less prominent or widely distributed. Nevertheless, at each site, regardless of years and stage of the melting season, we collected where possible two adjacent samples: one clean snow sample (no macroscopically visible particles) and one red snow sample (with visible particles). The exceptions were Solheimajökull, sampled in 2013, where snow patches were only present at the edges of deep crevasses and thus only bare, gray ice was sampled and Eyafjallajökull sampled from 2014, where only red snow and no “clean” snow could be found at the late stage in the melt season. It is important to note that all samples that are labeled “red snow” or “gray ice” in Table 1 always contained high loads of volcanic ash or dust debris, while the samples termed “clean snow” did not contain ash, dust or any macroscopically visible biomass and filtering of the clean snow did not result in enough biomass for genomic or other analyses of the particulates.

Table 1.

Overview of samples, locations, coordinates and field measurements.

| Sample label | Glacier | Sample description | Collection date | GPS location [UTM] | Elevation [m] | pH | Snow temp. [°C] | PAR [W/m2] | UV-A [W/m2] | UV-B [W/m2] | Albedo [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE-12_1 | Snaefellsjökull | Red snow | 26/07/2012 | 27W 0371148 E, 7190818 N | 695 | ||||||

| ICE-12_2 | Drangajökull | Red snow | 27/07/2012 | 27W 0442009 E, 7334293 N | 230 | 5.27 | 0.3 | ||||

| ICE-12_3 | Drangajökull | Red snow | 27/07/2012 | 27W 0442125 E, 7334250 N | 196 | 6.15 | 0 | ||||

| ICE-12_4 | Laugafell snow field | Red snow | 29/07/2013 | 27W 0632892 E, 7222179 N | 908 | 4.96 | 237 | 21.2 | 1.24 | 42 | |

| ICE-12_5 | Laugafell snow field | Clean snow | 29/07/2013 | 27W 0632892 E, 7222179 N | 908 | 5.68 | 0.1 | 254 | 39 | ||

| ICE-12_6 | Hofsjökull | Red snow | 29/07/2013 | 27W 0600998 E, 7206978 N | 906 | 6.44 | 0.5 | 104 | |||

| ICE-12_7 | Hofsjökull | Red snow | 29/07/2013 | 27W 0600998 E, 7206978 N | 906 | 6.47 | 0 | 98 | 19 | ||

| ICE-13_1 | Snaefellsjökull | Red snow | 02/06/2013 | 27W 0372788 E, 7188065 N | 461 | 5.46 | 0 | 100 | 20.8 | 0.61 | 64 |

| ICE-13_2 | Snaefellsjökull | Red snow | 02/06/2013 | 27W 0372427E, 7188287 N | 366 | 5.07 | 0.2 | ||||

| ICE-13_3 | Eyjafjallajökull | Clean snow | 07/06/2013 | 27V 0563957 E, 7056674 N | 1156 | 5.59 | 0.1 | 356 | 78 | ||

| ICE-13_4 | Eyjafjallajökull | Red snow | 07/06/2013 | 27V 0563563 E, 7056695 N | 1121 | 5.10 | 0.2 | 316 | 73 | ||

| ICE-13_5 | Eyjafjallajökull | Red snow | 07/06/2013 | 27V 0559557 E, 7056046 N | 736 | 5.50 | 0 | 94 | 33 | ||

| ICE-13_6 | Eyjafjallajökull | Red snow | 07/06/2013 | 27V 0559557 E, 7056046 N | 736 | 5.55 | 0 | 89 | 65 | ||

| ICE-13_7 | Mýrdalsjökull | Clean snow | 07/06/2013 | 27V 0587893 E, 7049973 N | 925 | 5.20 | 1 | 245 | 89 | ||

| ICE-13_8 | Mýrdalsjökull | Red snow | 07/06/2013 | 27V 0588165 E, 7049601 N | 923 | 5.86 | 1 | 150 | 18.6 | 0.42 | 72 |

| ICE-13_9 | Mýrdalsjökull | Red snow | 07/06/2013 | 27V 0588165 E, 7049601 N | 923 | 5.96 | 0 | 118 | 55 | ||

| ICE-13_10 | Solheimajökull | Gray ice | 07/06/2013 | 27V 0582585 E, 7046897 N | 244 | 127 | 42 | ||||

| ICE-13_11 | Vatnajökull | Clean snow | 08/06/2013 | 28W 0459058 E, 7125767 N | 767 | 5.98 | 0 | 173 | 80 | ||

| ICE-13_12 | Vatnajökull | Gray ice | 08/06/2013 | 28W 0459058 E, 7125451 N | 695 | 136 | 19 | 0.06 | 18 | ||

| ICE-13_13 | Vatnajökull | Red snow | 08/06/2013 | 28W 0459058 E, 7125451 N | 695 | 7.08 | 0 | 137 | 27 | ||

| ICE-13_14 | Vatnajökull | Red snow | 08/06/2013 | 28W 0459058 E, 7125451 N | 695 | 6.04 | 0 | 148 | 42 | ||

| ICE-13_15 | Vatnajökull | Red snow | 08/06/2013 | 28W 0459058 E, 7125451 N | 695 | 5.83 | 0 | 151 | 47 | ||

| ICE-13_16 | Langjökull | Red snow | 10/06/2013 | 27W 0521378 E, 7168876 N | 812 | 6.53 | 0 | 52 | 6.42 | 0.21 | 60 |

| ICE-13_17 | Langjökull | Clean snow | 10/06/2013 | 27W 0521378 E, 7168876 N | 812 | 6.26 | 0 | 54 | 67 | ||

| ICE-13_18 | Langjökull | Red snow | 10/06/2013 | 27W 0521378 E, 7168876 N | 812 | 5.93 | 0 | 88 | 43 | ||

| ICE-13_19 | Langjökull | Red snow | 10/06/2013 | 27W 0521378 E, 7168876 N | 812 | 5.89 | 0 | 96 | 47 | ||

| ICE-13_21 | Snaefellsjökull | Red snow | 12/06/2013 | 27W 0370323 E, 7188655 N | 705 | 5.31 | 0 | 117 | 57 | ||

| ICE-13_22 | Snaefellsjökull | Clean snow | 12/06/2013 | 27W 0370323 E, 7188655 N | 705 | 5.84 | 0 | 122 | 71 | ||

| ICE-13_23 | Snaefellsjökull | Red snow | 12/06/2013 | 27W 0370323 E, 7188655 N | 705 | 6.19 | 0 | 170 | 73 | ||

| ICE-13_24 | Snaefellsjökull | Red snow | 12/06/2013 | 27W 0370323 E, 7188655 N | 705 | 5.96 | 0 | 195 | 51 | ||

| ICE-14_1 | Eyjafjallajökull | Red snow | 28/08/2014 | 27V 0577039 E, 7057638 N | 1004 | 7.73 | 0 | ||||

| ICE-14_1 | Eyjafjallajökull | Red snow | 28/08/2014 | 27V 0577174 E, 7057468 N | 1024 | 7.78 | 0 | ||||

| ICE_14_3 | Eyjafjallajökull | Red snow | 28/08/2014 | 27V 0577101 E, 7057803 N | 1010 | 7.91 | 0 |

Conductivity in all samples was 0 μS/cm.

Figure 1.

Map showing the 2012 (red dots), 2013 (blue dots), and 2014 (green dot) sampling sites (further details see Table 1). Image Source Google Earth (June 2013).

At each sampling point prior to sample collection, snow temperature, pH and conductivity were measured in the field using a daily calibrated multi-meter (Hanna instruments, HI 98129). Irradiation was measured using a radiometer with specific PAR, UV-A and UV-B sensors (SolarLight, PMA2100). Surface albedo was calculated by taking the ratio of reflected to incident radiation (400–700 nm range) as previously described (Lutz et al., 2014). Snow samples were collected either in sterile 50 mL centrifuge tubes (red snow) or large sterile Whirl-Pak® bags (clean snow) and in 250 mL pre-ashed (450°C >4 h) glass jars for all organic analyses. The snow samples were slowly melted at room temperature over a ~ 6 h period. All samples were processed (filtered, acidified, etc.) within max 6–8 h post collection in order to preserve them for various analyses in the home laboratory. All DNA and filtered organic samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and returned to Leeds in a cryo-shipper after which they were stored at −80°C until further processing. All processed inorganic samples were stored cold (4°C, in the dark) until analyzed.

Bio- and geochemical analyses

Several of the methods used to analyze solutions and solid samples described below are equivalent to the methods employed and explained in detail in Lutz et al. (2014). Here we briefly summarize all standard aqueous and solid analyses and explain in detail those methods that are new compared to our previous work. For anion analysis by ion chromatography (IC, Dionex, 5% precision) and cation analysis by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Agilent, 3% precision), samples were filtered through 0.2 μM cellulose-acetate filters into either pre-acidified (Aristar grade HNO3) Nalgene HDPE bottles (cations) or into un-acidified 15 mL centrifuge tubes (anions). For dissolved organic carbon (DOC), PO4 and organic particulate analysis, samples collected in ashed glass jars were filtered through ashed 0.7 μm glass fiber filters (GFF) directly into pre-acidified (Aristar grade HCl) vials using glass syringes and metal filter holders. PO4 was analyzed by segmented flow-injection analyses (AutoAnalyser3, Seal Analytical, 5% precision), while DOC was analyzed on a total organic carbon analyzer (TOC, Shimadzu TOC-V, 3% precision). The GFF filters containing particulates were preserved in pre-ashed aluminum foil for pigment and fatty acid analyses. Pigment compositions (chlorophylls and carotenoids) were analyzed using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1220 Infinity, 5% precision) after extraction in dimethylformamide and quantified using pigment standards (chlorophylls: Sigma, carotenoids: Carotenature). Fatty acids were extracted in dichloromethane:methanol (2:1, v:v) in two steps and extracts were combined, followed by transesterification in 3 M methanolic HCl for 20 min at 65°C and three consecutive extractions in isohexane. Tricosanoic acid methyl ester (Sigma) was used as an internal standard and a 37 component FAME mix (Supelco) as external standard. The extracts were separated by gas chromatography (Thermo Scientific, Trace1300, 5% precision), spectra were recorded on a mass spectrometer (ISQ Single Quadrupole) and quantified on a flame ionization detector (FID). Particulates were also collected on 0.2 μm polycarbonate filters for mineralogical analysis by X-ray diffraction (XRD, D8 Bruker). Total carbon (TC), nitrogen (TN) and sulfur (TS) and nitrogen isotopes were analyzed by pyrolysis at 1500°C (Vario Pyro Cube, Elementar Inc.) followed by mass spectrometry (Isoprime Mass Spectrometer, 0.1% precision). For imaging by light microscopy (LM, Leica DM750) unconcentrated samples were preserved in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and images recorded through a 63× objective. The hydrogeochemical modeling software PHREEQC (Parkhurst, 1995, using the LLNL database) was used to determine the saturation indexes for our aqueous solutions.

DNA sequencing

All samples contained low amounts of biomass and therefore, red snow samples from the same glacier and same collection year were pooled in order to obtain a sufficient quantity of DNA for sequencing (Table 6). Total DNA was extracted using the PowerSoil® DNA Isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories). 16S rRNA genes were amplified using bacterial primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG) and 357R (5′-CTGCTGCCTYCCGTA) (tagged with the Ion Torrent adapter sequences and MID barcode) spanning the V1–V2 hypervariable regions. 18S rRNA genes were amplified using the eukaryotic primers 528F (5′-GCGGTAATTCCAGCTCCAA) and 706R (5′-AATCCRAGAATTTCACCTCT) (Cheung et al., 2010) (tagged with the Ion Torrent adapter sequences and MID barcode) spanning the V4–V5 hypervariable region. Polymerase chain reactions (PCR) were performed using Platinum® PCR SuperMix High Fidelity according to manufacturer's protocols. Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min was followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s and elongation at 72°C for 30 s. Final elongation was at 72°C for 7 min. Archaeal 16S rRNA genes were amplified following a nested PCR approach. The first PCR reaction was carried out using primers 20F and 915R. Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min was followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 62°C for 30 s and elongation at 72°C for 180 s. Final elongation was at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR product was used as template for the second PCR reaction with primers 21F (5′-TCCGGTTGATCCYGCCGG) and 519R (5′- GWATTACCGCGGCKGCTG) (tagged with the Ion Torrent adapter sequences and MID barcode) spanning the V1–V2 hypervariable region. Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min was followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s and elongation at 72°C for 30 s. Final elongation was at 72°C for 7 min. All PCRs were carried out in triplicates to reduce amplification bias and in reaction volumes of 1 × 25 and 2 × 12.5 μl. All pre-amplification steps were done in a laminar flow hood with DNA-free certified plastic ware and filter tips. The pooled amplicons were purified with AMPure XP beads (Agencourt©) with a bead to DNA ratio of 0.6 to remove nucleotides, salts and primers and analyzed on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyser (Agilent Technologies) with the High Sensitivity DNA kit (Agilent Technologies) and quality, size and concentration were determined. Sequencing was performed on an Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine using the Ion Xpress™ Template Kit and the Ion 314TM chip following manufacturer's protocols. The only exceptions were the archaeal amplicons of samples ICE-14_1, ICE-14_2 and ICE-14_3 which were sequenced on an Ion 316TM chip. The raw sequence data was processed in QIIME (Caporaso et al., 2010). Barcodes and adapter sequences were removed from each sequence. Filtering of sequences was performed using an average cutoff of Q20 over a 350 bp range. Reads shorter than 200 bp were removed. OTUs were picked de novo using a threshold of 99, 97, and 95% identity. Taxonomic identities were assigned for representative sequences of each OTU using the reference databases Greengenes for bacteria and archaea. The Silva database (DeSantis et al., 2006; extended with additional 223 sequences of cryophilic algae kindly provided by Dr. Thomas Leya from the CCCryo—Culture Collection of Cryophilic Algae, Fraunhofer IZI-BB) was used for eukaryotes. Data were aligned using PyNAST and a 0.80 confidence threshold. Singletons were excluded from the analysis. For bacterial sequence matching, plant plastids were removed from the data set prior to further analysis. For eukaryotic sequence matching Chloroplastida were pulled out of the data set and stored in a separate OTU table. In order to focus upon algal diversity, sequences matching Embryophyta (e.g., moss, fern) were removed from the data set. For archaea, sequences matching bacteria were removed. Finally, for diversity analyses samples were rarefied to the smallest sequence number and Shannon indices were calculated in QIIME. A matrix of each OTU table representing relative abundance was imported into Past3 (Hammer et al., 2012) for multivariate statistical analyses (principal component analysis, PCA). Representative sequences of the major algal species found in all samples were imported into Geneious (7.1.3., Biomatters) for phylogenetic tree building based on neighbor-joining. Sequences have been deposited to the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under accession number PRJEB8832.

Results

Physico-, geochemical, and biochemical analyses

Snow temperatures at each collection site varied only over a narrow range between 0 and 1.0°C (Table 1). The pH was slightly acidic for most sites and there were no clear differences between red algal (4.96–6.53) or clean snow (5.20–6.26) sites. Only the samples collected in 2014 from snow fields on fresh volcanic lava and that had high contents of fresh volcanic ash inputs from the 2010 Eyafjallajökull eruption showed a more alkaline pH (7.73–7.91). This is not surprising since fresh volcanic glass is highly reactive and buffers any waters in contact with it to a pH between 7.5 and 8 (Oelkers and Gislason, 2001; Gislason and Oelkers, 2003). The albedo values differed from clean snow (76% ± 8) to sites with algal growth (56% ± 14; Table 1). Aqueous geochemical analysis (Table 2) revealed low values (<ppm) for all cations and anions in our samples. Geochemical modeling confirmed that our solutions were undersaturated with respect to most solid phases except for Fe oxides (goethite, hematite) and As-hydroxides (boehmite, diaspore, gibbsite, Table S7). However, values for DOC varied dramatically and ranged from 15 to 200 μM (Table 2). The total carbon contents (TC, in % of total dry filtered particulate weight) were below 2% in all sites with one exception (ICE-13_1, Snaefellsjökull) where a TC content of 7.6% was found (Table 3). In all analyzed samples the total nitrogen contents were below 0.3% and total sulfur below 0.1%. There were no large variations in N and S among the sample sites. Carbon to nitrogen (C/N) ratios varied over a broad range from 1.7 (C/N) ratios varied over a broad range from 1.7 (ICE-13_8, Mýrdalsjökull) to 28.5 (ICE-13_1, Snaefellsjökull). Nitrogen isotopes were overall negative and ranged from −11.2 to −4.2‰.

Table 2.

Combined organic (DOC) and inorganic aqueous chemical data for the samples collected in 2012 and 2013.

| Sample | DOC [μM C] | PO3−4 [nM P] | NO−3 | SO2−4 | Cl− | Al | Ba | Ca | Cr | Cu | Fe | K | Mg | Mn | Na | Ni | Pb | S | Si | Sr | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE-12_1 | < | 171 | 243 | 3 | 1 | 15 | < | < | 5 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 124 | < | < | 76 | < | 2 | |||

| ICE-12_2 | < | < | 135 | 560 | 7 | 200 | 2 | 1 | 337 | 55 | 131 | 5 | 214 | 1 | < | 626 | 2 | 22 | |||

| ICE-12_3 | < | < | 114 | 17 | 7 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 38 | 11 | < | 99 | < | < | 40 | < | 25 | |||

| ICE-12_4 | < | 181 | 275 | 4 | 13 | 26 | < | < | 3 | 44 | 13 | 1 | 234 | < | < | 483 | < | 30 | |||

| ICE-12_5 | 99 | < | 125 | 6 | 13 | 41 | < | < | 6 | 34 | 4 | < | 57 | < | < | 24 | < | 31 | |||

| ICE-12_6 | < | < | 100 | 12 | 11 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 40 | 33 | 15 | 2 | 98 | 3 | < | 264 | < | 40 | |||

| ICE-12_7 | < | < | 275 | 101 | 22 | 166 | < | 1 | 84 | 73 | 113 | 5 | 231 | < | < | 734 | 1 | 30 | |||

| ICE-13_1 | 94 | 117.9 | 371 | 127 | 255 | 1.4 | < | 45.3 | < | < | 4.6 | < | 15.1 | 1.4 | 209 | < | < | < | 63.3 | 0.49 | 1.6 |

| ICE-13_2 | 200 | 89.2 | < | < | 176 | 1.4 | < | 37.3 | < | < | 5.1 | < | 10.4 | 1.3 | 132 | < | < | < | 72.5 | 0.38 | 2 |

| ICE-13_3 | 92.7 | < | < | 147 | 0.59 | < | 4.8 | < | < | 8.9 | < | 2.8 | 0.24 | 89.3 | < | < | < | 10.1 | < | 0.28 | |

| ICE-13_4 | 82 | 119.8 | < | < | 363 | 1.7 | < | 18.4 | < | < | 1.3 | 29.8 | 11.8 | 0.84 | 245 | < | < | < | 36.9 | 0.26 | 0.19 |

| ICE-13_5 | 33 | 84.9 | < | 127 | 377 | 6.4 | < | 86.6 | < | < | 12.9 | 32.3 | 46.4 | 4.9 | 266 | < | < | < | 193 | 0.68 | 0.22 |

| ICE-13_6 | 86 | 78.6 | < | < | 275 | 1.7 | < | 19.2 | < | < | 3.2 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 1 | 145 | < | < | < | 54.3 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| ICE-13_7 | 43.5 | < | 128 | 539 | 0.68 | < | 1.1 | < | < | 0.3 | < | 0.8 | 0.05 | 3.3 | < | < | < | 10.8 | < | 2.3 | |

| ICE-13_8 | 58 | 172.0 | < | < | 488 | 4.7 | < | 94.5 | < | < | 9.1 | 28.7 | 34.2 | 0.95 | 398 | < | < | < | 94.5 | 0.43 | 0.22 |

| ICE-13_9 | 15 | 296.3 | < | < | 156 | 14.7 | < | 132 | < | < | 29.7 | 30.8 | 54.5 | 2.2 | 156 | < | < | < | 330 | 0.57 | < |

| ICE-13_10 | < | 145 | 95 | 1.9 | < | 20.1 | < | < | 2.1 | 15.4 | 7.5 | 0.72 | 126 | < | < | 20.5 | 21.1 | 0.14 | 1.6 | ||

| ICE-13_11 | 201 | 74.7 | 100 | < | 0 | 0.51 | < | 5.9 | < | < | 0.4 | < | 2.2 | 0.06 | 41.2 | < | < | < | 20.2 | < | 1.1 |

| ICE-13_12 | 92 | 230.4 | < | < | 0 | 11.4 | 0.14 | 89.2 | 6.2 | 0.18 | 14.5 | < | 30.8 | 3.1 | 76.1 | < | 0.02 | < | 63.4 | 0.57 | 1.8 |

| ICE-13_13 | 50 | 89.3 | < | < | 274 | 0.98 | < | 31 | < | < | 1.1 | < | 9.9 | 0.44 | 198 | < | < | < | 20.3 | 0.17 | 0.7 |

| ICE-13_14 | 37 | 308.5 | < | < | 371 | 4.6 | < | 84.2 | < | < | 8.8 | 43.1 | 53.9 | 2.6 | 188 | < | < | < | 306 | 0.45 | 0.22 |

| ICE-13_15 | 33 | 262.7 | < | < | 100 | 5.8 | < | 48 | < | < | 11.9 | < | 28.9 | 1.4 | 98.7 | < | < | < | 185 | 0.23 | < |

| ICE-13_16 | 54 | 53.9 | 3499 | < | 0 | 1.2 | < | 12.8 | < | < | 3.1 | < | 5.4 | 0.57 | 47 | < | < | < | 35.8 | 0.12 | 0.96 |

| ICE-13_17 | 26 | 448.9 | 225 | < | 72 | 1.4 | < | < | < | < | 1.1 | 16.4 | 0.8 | 0.05 | 67.8 | < | < | < | 10.5 | < | 0.89 |

| ICE-13_18 | 149 | 78.3 | < | < | 79 | 8.3 | < | 20.6 | < | 0.39 | 2.1 | 17.6 | 6.5 | 0.36 | 70.5 | < | < | < | 69.8 | 0.21 | 0.76 |

| ICE-13_19 | 41 | 62.8 | < | < | 486 | 8.1 | < | 24.5 | < | 0.32 | 2.1 | < | 7.8 | 0.33 | 385 | < | 0.56 | < | 64.7 | 0.23 | 1 |

| ICE-13_21 | 58 | 54.5 | < | < | 718 | 2.1 | < | 26 | < | < | 9.1 | 18.6 | 14.4 | 0.95 | 523 | < | 0.03 | < | 18.8 | 0.26 | 3.6 |

| ICE-13_22 | 103 | 85.8 | < | < | 881 | 1.1 | < | 12.5 | < | < | 1.3 | < | 18.7 | 0.08 | 658 | < | 0.02 | 18.8 | 10.1 | 0.18 | 0.61 |

| ICE-13_23 | 59 | 30.2 | 456 | < | 742 | 0.52 | < | 3.9 | 0.27 | < | 2.3 | 12.5 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 577 | < | < | < | 23.2 | < | 0.29 |

| ICE-13_24 | 58 | 145.8 | 468 | 145 | 611 | 1.8 | < | 7.9 | < | < | 7.7 | < | 11.4 | 1 | 386 | < | < | 16.4 | 38.3 | 0.19 | 0.12 |

All values except DOC and PO3−4 are given in ppb; NO3−, SO2−4, and Cl− all determined by IC, all others analyzed by ICP-MS; limit of detection (LOD) for IC: NO−3 = 96 ppb, Cl− = 72 ppb, SO2−4 = 121 ppb, LOD's for ICP-MS: Al, Ba, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mg, Ni, Si, Sr, Zn = 0.1 ppb, Bi, Cd, Mn, Pb = 0.01 ppb, Ca, Na = 1 ppb, K,P,S = 10 ppb, no value indicates no measurement available for the respective sample; note Co was < LOD in all samples and Co was < LOD in all samples except in ICE-13_19 (0.07).

Table 3.

Total carbon (TC(s)), total nitrogen (TN(s)), and total sulfur (TS(s)) (all based on % of dry weight of sample) as well as the nitrogen isotope values from the analyzed particulates in the 2012 and 2013 collected red snow and gray ice samples that contained enough particulate material for analyses; listed are also the solid C/N(s) ratio calculated from TC and TN values.

| Sample ID | Glacier | TC(s) [%] | TN(s) [%] | TS(s) [%] | C/N(s) | d15N(s) [‰] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE-12_7 | Hofsjökull | 0.64 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 5.4 | −11.2 |

| ICE-13_1 | Snaefellsjökull | 7.62 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 28.5 | |

| ICE-13_2 | Snaefellsjökull | 1.69 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 20.7 | |

| ICE-13_4 | Eyafjallajökull | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 6.4 | |

| ICE-13_5 | Eyafjallajökull | 1.27 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 18.4 | −4.2 |

| ICE-13_6 | Eyafjallajökull | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 19.0 | −7.0 |

| ICE-13_8 | Mýrdalsjökull | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 1.7 | |

| ICE-13_9 | Mýrdalsjökull | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 4.3 | |

| ICE-13_10 | Solheimajökull | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 19.4 | |

| ICE-13_12 | Vatnajökull | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 7.4 | −6.2 |

| ICE-13_14 | Vatnajökull | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 3.6 | −7.5 |

| ICE-13_15 | Vatnajökull | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 6.3 | |

| ICE-13_16 | Langjökull | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 10.0 | −5.7 |

| ICE-13_18 | Langjökull | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 8.3 | |

| ICE-13_21 | Snaefellsjökull | 1.20 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 12.2 | −4.6 |

| ICE-13_24 | Snaefellsjökull | 1.08 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 10.7 | −3.9 |

The fatty acid distribution was similar in all analyzed snow samples and characterized by predominance of saturated C16 and C18 fatty acids (up to 100%; Table 5 and Table S1). The most abundant unsaturated fatty acids were C16:1, C18:1, C18:2, C18:3. Among these C18:1 was the most prominent fatty acid and the highest proportion of unsaturated fatty acids was found on Drangajökull and Hofsjökull (63–80%), the two glaciers sampled late in the 2012 season. Pigment analysis revealed that chlorophylls (Chl a and Chl b) made up the largest proportion in all samples with a range of 31–100% of total pigments, followed by secondary carotenoids (between 0 and 69%) and primary carotenoids (violaxanthin, zeaxanthin, lutein, β-carotene; up to 8%). Samples in 2012 and 2014 were collected later in the melting season and thus not surprisingly showed higher secondary carotenoids contents (up to 69%). The only secondary carotenoid identified was astaxanthin and the trans-configuration of astaxanthin was prevalent over the cis-configuration and astaxanthin mono esters could also be identified.

Table 5.

Fatty acid composition of the red snow samples collected in 2012 and 2013. Fatty acid compounds are reported as percentage of total fatty acids.

| Compound | Glacier | C16:0 | C16:1 | C18:0 | C18:1 | C18:2 | C18:3 | SFA | MUFA | PUFA | UFA | Ratio SFA/UFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE-12_2 | Drangajökull | 20 | 8 | 0 | 58 | 7 | 7 | 20 | 67 | 13 | 80 | 0.2 |

| ICE-12_3 | Drangajökull | 18 | 8 | 10 | 52 | 5 | 4 | 31 | 60 | 9 | 69 | 0.4 |

| ICE-12_5 | Laugafell | 16 | 3 | 57 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 73 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 3.6 |

| ICE-12_6 | Hofsjökull | 18 | 2 | 18 | 53 | 5 | 3 | 37 | 55 | 7 | 63 | 0.6 |

| ICE-12_7 | Hofsjökull | 14 | 4 | 3 | 43 | 27 | 0 | 22 | 48 | 31 | 78 | 0.3 |

| ICE-13_1 | Snaefellsjökull | 16 | 16 | 17 | 13 | 6 | 3 | 40 | 29 | 9 | 39 | 1.0 |

| ICE-13_2 | Snaefellsjökull | 19 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 11 | 6 | 39 | 26 | 17 | 43 | 0.9 |

| ICE-13_4 | Eyafjallajökull | 94 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 94 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 16.0 |

| ICE-13_5 | Eyafjallajökull | 25 | 8 | 16 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 52 | 17 | 27 | 44 | 1.2 |

| ICE-13_6 | Eyafjallajökull | 21 | 2 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 14 | 41 | 15 | 29 | 44 | 0.9 |

| ICE-13_8 | Mýrdalsjökull | 42 | 0 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ICE-13_9 | Mýrdalsjökull | 38 | 0 | 38 | 16 | 9 | 0 | 75 | 16 | 9 | 25 | 3.1 |

| ICE-13_12 | Vatnajökull | 22 | 5 | 12 | 20 | 6 | 16 | 40 | 25 | 35 | 60 | 0.7 |

| ICE-13_14 | Vatnajökull | 26 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 14 | 29 | 49 | 5 | 44 | 50 | 0.98 |

| ICE-13_15 | Vatnajökull | 26 | 0 | 17 | 16 | 4 | 5 | 60 | 16 | 9 | 25 | 2.4 |

| ICE-13_16 | Langjökull | 24 | 2 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 45 | 18 | 36 | 53 | 0.8 |

| ICE-13_18 | Langjökull | 25 | 4 | 30 | 16 | 9 | 6 | 65 | 20 | 15 | 35 | 1.9 |

| ICE-13_19 | Langjökull | 33 | 2 | 49 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 88 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 7.0 |

| ICE-13_21 | Snaefellsjökull | 27 | 3 | 9 | 21 | 7 | 16 | 44 | 22 | 29 | 51 | 0.9 |

| ICE-13_24 | Snaefellsjökull | 28 | 2 | 12 | 16 | 7 | 7 | 61 | 17 | 14 | 31 | 2.0 |

Most prominent fatty acids (full table see SI) are reported as well as total saturated (SFA), total monounsaturated (MUFA), total polyunsaturated (PUFA), total unsaturated (UFA) fatty acids, and the ratios of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids.

The mineralogical analysis of the particulates revealed that the dominant minerals in all samples were quartz, plagioclase (albite, anorthite), and pyroxene with some contributions from clays, basaltic glass and hematite (Figure S1). Hematite was one of the main supersaturated mineral phases in our solutions as shown by the geochemical modeling (Table S7). This bulk mineralogical composition varied little among all collected samples and matches the typical mineralogy of the fresh ash (Jones and Gislason, 2008) and dust from the prime rocks in Iceland, which can be basaltic to rhyolitic (Jakobsson et al., 2008).

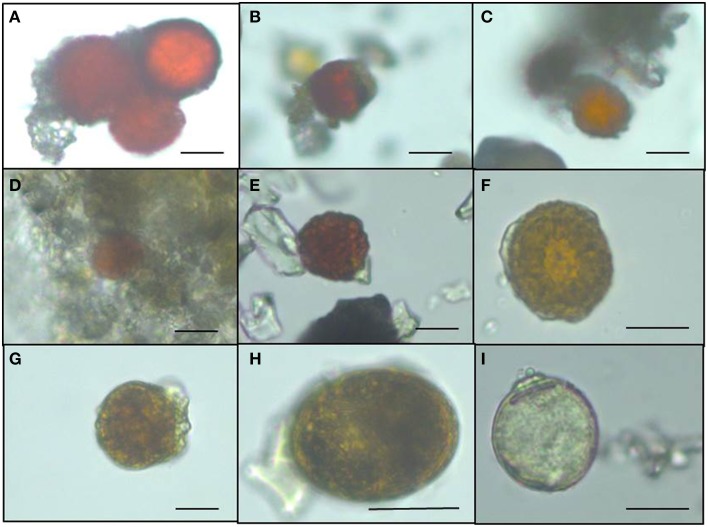

Species composition

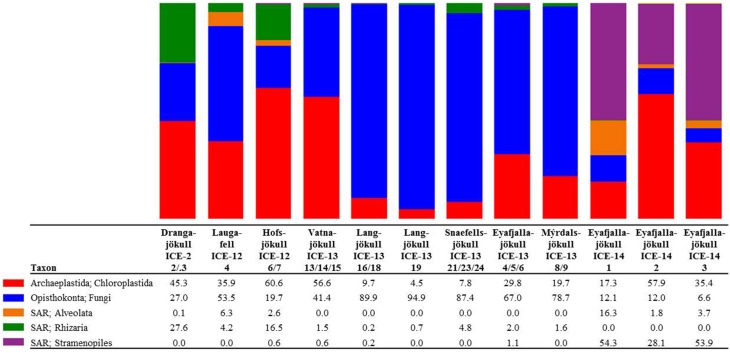

The presence of snow algae was confirmed in all collected samples by light microscopy (Figure 2). Samples from 2012, collected in the late melt season showed overall more red pigmentation, whereas in 2013 samples (collected at the beginning of the melt season) contained more green and yellow pigmented cells (Figure 2 and Table 4). Since algal species identification by microscopy can be deceiving due to various morphological changes during their life stages, targeted DNA sequencing was carried out to reveal algal species composition as well as the full microbial diversity (other micro-eukaryotes, bacteria, archaea) associated with snow algal sites. From all sequences that were amplified with the 18S rRNA primers, a total of 108,790 sequences (12 samples in total; Table 6) passed the QIIME quality pipeline (quality score >20) corresponding to 2811 operational taxonomic units that clustered at 97% sequence identity. Clustering of OTUs at 99, 97, or 95% sequence similarity resulted in differences for OTUs counts (Table S2), however not for taxa assignments and relative abundance of taxa (Tables S3–S5) and therefore, a 97% similarity was chosen to be most representative for all further analyses. OTUs aligned and assigned to our extended Silva database (see Methods) on all phylogenetic levels revealed differences between the eight sampling sites. Chloroplastida (green algae) and Fungi made up the largest proportion of eukaryotic sequences followed by Alveolata (Figure 3). All samples collected in 2013 (except Vatnajökull) showed a much higher abundance of sequences assigned to Fungi (67.0–94.9% of total sequences as opposed to 4.5–29.8% of total sequences in 2012, except Laugafell), with the most abundant class represented by the Microbotryomycetes (Basidomycota) [see full OTU tables in the Supplementary Information (SI) files]. Samples collected in 2012 and 2014 (except Eyafjallajökull, ICE-14_1) showed a higher abundance of Chloroplastida (35.4–60.6%; compared to fungi: 6.6–53.5%) and also the presence of Stramenopiles (e.g., Chrysophyceae; Eyafjallajökull sampled in 2014), Rhizaria (e.g., Cercozoa; Drangajökull and Hofsjökull sampled in 2012) and Alveolata (e.g., Ciliophora; Laugafell sampled in 2012 and Eyafjallajökull in 2014). Shannon indices (Table 6) for all eukaryotes varied over a broad range from H′ = 3.75 (Eyafjallajökull, ICE-14_2) to H′ = 6.02 (Laugafell).

Figure 2.

Light microscopy images of snow algae from the different sampling sites revealing the more red pigmented algae collected in 2012 compared to the less red pigmented algae sampled in 2013. (A) Drangajökull (ICE-12_3), (B) Laugafell (ICE-12_4), (C) Hofsjökull (ICE-12_6), (D) Snaefellsjökull (ICE-13_2), (E) Eyafjallajökull (ICE-13_5), (F) Mýrdalsjökull (ICE-13_8), (G) Vatnajökull (ICE-13_14), (H) Langjökull (ICE-13_16), (I) Snaefellsjökull (ICE-13_21).

Table 4.

Pigment composition of red snow samples that contained enough particulate material for analysis.

| Sample ID | Glacier | Chl a [μg/L] | Chl b [μg/L] | Vio [μg/L] | Zea [μg/L] | Lut [μg/L] | β-Car [μg/L] | trans- Ast [μg/L] | cis-Ast mono esters [μg/L] | trans-Ast mono esters [μg/L] | Total chlorophylls [%] | Total primary carotenoids [%] | Total secondary carotenoids [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE-12_1 | Snaefellsjökull | 10,528 | 1739 | 552 | 980 | 142 | 88 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| ICE-12_3 | Drangajökull | 4673 | 12,207 | 34 | 580 | 545 | 94 | 0 | 6 | ||||

| ICE-12_4 | Laugafell | 5816 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| ICE-12_7 | Hofsjökull | 8306 | 502 | 94 | 0 | 6 | |||||||

| ICE-13_5 | Eyjafjallajökull | 3079 | 255 | 4 | 92 | 8 | 0 | ||||||

| ICE-13_8 | Mýrdalsjökull | 2504 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| ICE-13_15 | Vatnajökull | 8123 | 40 | 67 | 99 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| ICE-13_16 | Langjökull | 8280 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| ICE-13_21 | Snaefellsjökull | 20,120 | 18 | 250 | 240 | 98 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| ICE-13_23 | Snaefellsjökull | 16,016 | 13 | 257 | 13 | 338 | 96 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| ICE-14_1 | Eyjafjallajökull | 62 | 34 | 157 | 31 | 0 | 69 | ||||||

| ICE-14_2 | Eyjafjallajökull | 87 | 46 | 28 | 78 | 0 | 22 | ||||||

| ICE-14_3 | Eyjafjallajökull | 138 | 69 | 31 | 83 | 0 | 17 |

Individual pigments were quantified in ug/L and reported as total chlorophylls, total primary carotenoids and total secondary carotenoids in % of total pigments.

Table 6.

Number of sequences (seqs) for the pooled red snow samples for each glacier and the respective Shannon diversity index (H′).

| Glacier | Pooled | Eukaryotes | Bacteria | Archaea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | Raw seqs | Seqs after QC | H′ euk | Seqs assigned to algae | H′ algae | Raw seqs | Seqs after QC | Seqs assigned to bac | H′ bac | Raw seqs | Seqs after QC | Seqs assigned to arch | |

| Drangajökull | ICE-12_2/3 | 5474 | 2013 | 5.55 | 714 | 4.50 | 6383 | 2333 | 513 | 5.13 | 9206 | 1443 | 4* |

| Laugafell | ICE-12_4 | 1908 | 597 | 6.02 | 89 | 4.47 | 2533 | 818 | 120 | 5.27 | 18323 | 6294 | 540 |

| Hofsjökull | ICE-12_6/7 | 6523 | 2168 | 5.61 | 792 | 3.88 | 3105 | 1336 | 339 | 5.38 | 18956 | 623 | 33 |

| Vatnajökull | ICE-13_13/14/15 | 9948 | 3438 | 5.02 | 66 | 4.51 | 2689 | 770 | 14 | 5.06 | 4034 | 646 | 210 |

| Langjökull | ICE-13_16/18 | 318 | 104 | 5.65 | 340 | 4.26 | 2398 | 913 | 111 | 5.29 | 5675 | 643 | 334 |

| Langjökull | ICE-13_19 | 7273 | 3065 | 4.99 | 38 | 4.26 | 6541 | 2153 | 444 | 5.14 | 14680 | 4129 | 77 |

| Snaefellsjökull | ICE-13_21/23/24 | 5123 | 1588 | 5.51 | 41 | 4.04 | 5850 | 2032 | 486 | 3.97 | 9800 | 3072 | 338 |

| Eyafjallajökull | ICE-13_4/5/6 | 2391 | 1072 | 5.14 | 37 | 4.21 | 12075 | 2897 | 55 | 5.27 | 10862 | 2268 | 0* |

| Mýrdalsjökull | ICE-13_8/9 | 2479 | 809 | 5.14 | 8 | n.d. | 406 | 97 | 2* | n.d. | 14760 | 5426 | 3* |

| Eyafjallajökull | ICE-14_1 | 34082 | 23959 | 5.11 | 3357 | 1.74 | 3842 | 1884 | 938 | 4.53 | 85138 | 66535 | 65727 |

| Eyafjallajökull | ICE-14_2 | 8716 | 6962 | 3.75 | 3307 | 1.07 | 3875 | 2145 | 1158 | 4.64 | 841 | 809 | 558 |

| Eyafjallajökull | ICE-14_3 | 24555 | 17196 | 4.96 | 4460 | 1.81 | 13230 | 6843 | 3390 | 4.59 | 28203 | 22350 | 21572 |

Removed from analysis due to low sequence numbers, n.d., not determined due to low sequence numbers.

Figure 3.

Distribution of 97% clustered OTUs aligned and assigned to eukaryotes. Values are the relative abundance of the taxa in percentage of total sequences and figure shows taxa with OTUs of a minimum total observation count of 0.1%. It is important to note that values are rounded to one digit; therefore, the abundance of a taxon with a value of 0.0 in one sample can range between 0.00 and 0.04%. A full OTU table can be found in the SI.

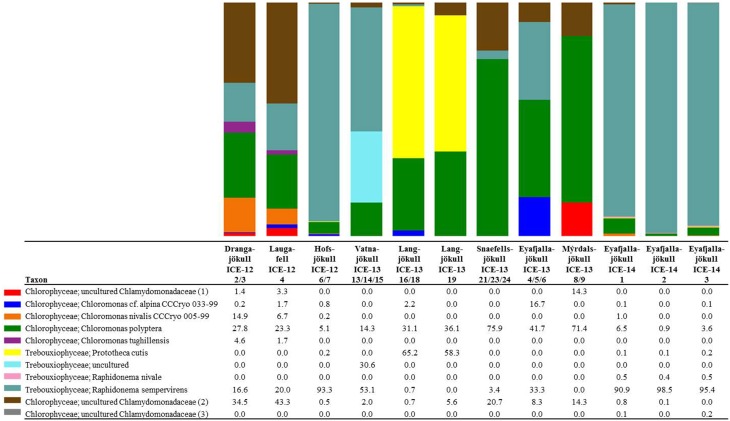

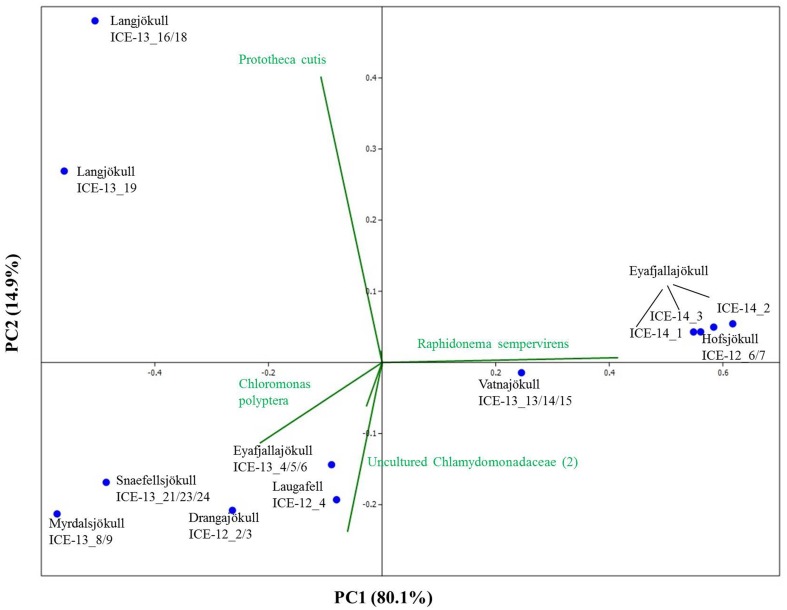

In order to investigate algal relative abundance all sequences corresponding to Chloroplastida were filtered from the main OTU table (Figure 4) with 567 OTUs remaining. Sequences matching Embryophyta showed low abundance with <7% for all samples with Vatnajökull being the exception and a value of 22% of total eukaryotic sequences. All sequences matching Embryophyta were removed from further analyses. The most abundant genera of algae belong to the Chlamydomonadaceae with Chloromonas polyptera being the dominant taxon. Two uncultured Chlamydomonadaceae species were also highly abundant and based on their 18S rRNA sequences they shared the highest sequence similarity (89–93% similarity) with other Chloromonas species found in our samples (Figure S2). The Trebouxiaceae were represented by Raphidonema sempervirens as the dominant taxon. Other Chloromonas species with intermediate abundance (up to 16.7%) were Chr. nivalis, Chr. alpina and Chr. tughillensis. Relative abundance of Chlamydomonas, Ancylonema, and Mesotaenium, that are typically described on glacial surfaces worldwide, was very low (<0.1%). In the Langjökull sample we also found a high number of sequences matching Prototheca cutis, a newly discovered pathogenic algae (Satoh et al., 2010), that may be derived from sledge dog feces that was abundant close to our sampling site. Full OTU tables can be found in the SI files. Shannon indices (Table 6) for algal species did not reveal large differences between sites (H′ = 3.88–4.51). The exceptions were the three samples collected from Eyafjallajökull in 2014, which showed a much lower diversity in the algae species (H′ = 1.07–1.81). The PCA analysis of the algal species (Figure 5) revealed taxonomic distance between sampling sites, however, separation was not caused by increasing geographic distance or collection time.

Figure 4.

Distribution of 97% clustered OTUs aligned and assigned to known algal species. Values are the relative abundance of the taxa in percentage of total sequences and figure shows taxa with OTUs of a minimum total observation count of 0.05%. It is important to note that values are rounded to one digit; therefore, the abundance of a taxon with a value of 0.0 in one sample can range between 0.00 and 0.04%. A full OTU table can be found in the SI.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis of algal species revealing taxonomic distance between sampling sites and species causing separation. However, taxonomic distance cannot be explained by increasing geographic distance or collection time.

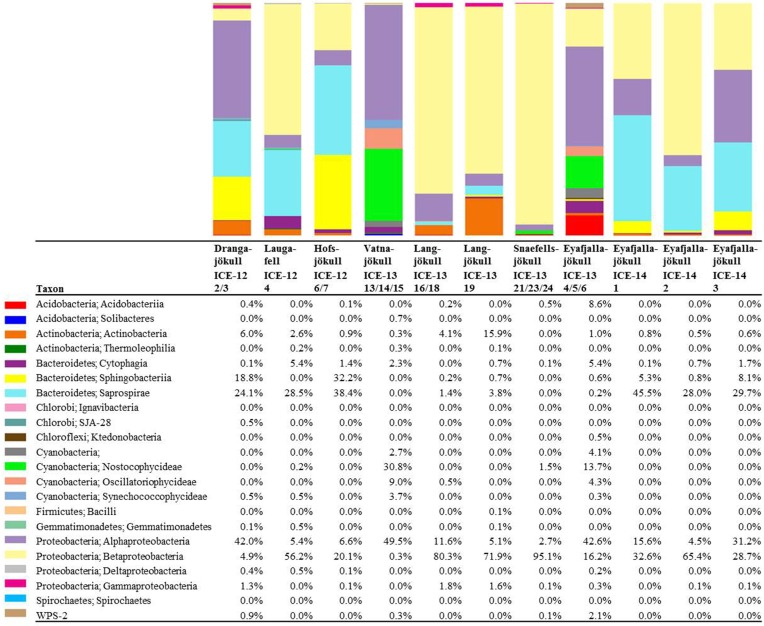

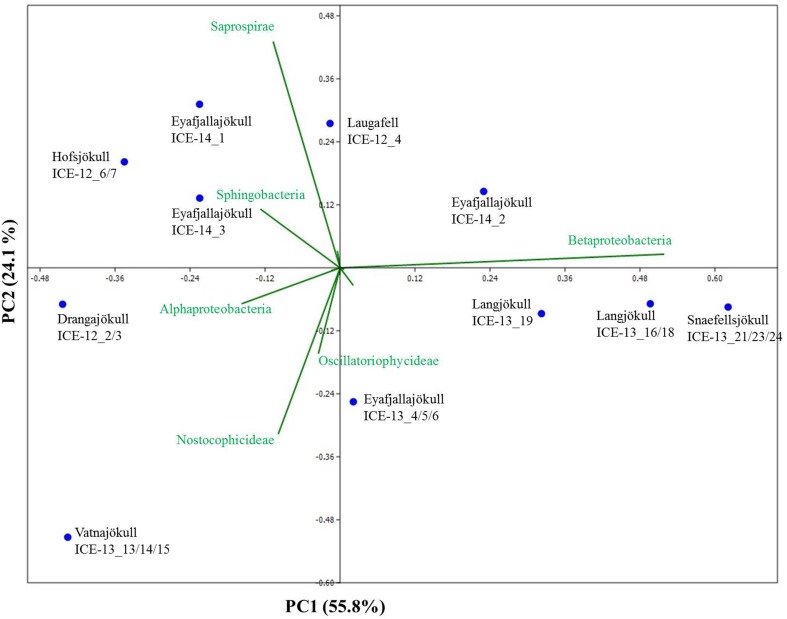

Bacterial primer amplification resulted in 24,221 sequences (12 samples in total) passing the QIIME quality pipeline corresponding to 1733 operational taxonomic units clustered at 97% sequence identity. Again similar values were derived when the relative abundance of taxa for OTUs were clustered at different similarities of 99, 97, and 95% (Table S5). OTUs aligned and assigned to the Greengenes database revealed differences between the eight sampling sites. The most abundant bacterial phyla were Proteobacteria, Bacteriodetes, and Cyanobacteria (see Figure 6). Within the Proteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria were most abundant followed by Alphaproteobacteria. Betaproteobacteria were present in high abundance on Snaefellsjökull (95.1%) in 2012, Langjökull in 2013 (80.3 and 71.9%) and Eyafjallajökull in 2014 (28.7–65.4%). In contrast, Alphaproteobacteria were most abundant on Vatnajökull (49.5%) and Eyafjallajökull in 2013 (42.6%), and Drangajökull (42.0 %) in 2012. Within the Bacteriodetes, the Sphingobacteria, and Saprospirae were the most abundant representative classes in the samples collected in 2012 and 2014. Sphingobacteria showed higher relative abundance on Hofsjökull (32.2%) and on Drangajökull (18.8%) whereas Saprospirae were more present on Hofsjökull (38.4%), in the three samples collected from Eyafjallajökull in 2014 (28.0–45.5%), Laugafell (28.5%) and Drangajökull 24.1%). Cyanobacteria (Nostocophycideae and Oscillatoriophycideae) were strongly represented only on Eyafjallajökull (74.0%), Vatnajökull (56.4%), and Langjökull (24.4%) collected in 2013. The Shannon indices for most bacterial samples (Table 6) varied over a narrow range (H′ = 5.13–5.38) and showed the same trend as for algae with similar values for all glaciers. Exceptions were again the three samples collected from Eyafjallajökull in 2014 (4.52–4.64) and the pooled Snaefellsjökull sample collected in 2013, which had the lowest bacterial diversity index among all bacterial samples (H′ = 3.97). PCA analysis (Figure 7) showed samples collected in 2012 and 2014 clustering together due to higher relative abundance of Bacteriodetes (Sphingobacteria, Saprospirae), whereas samples collected in 2013 clustered together due to higher proportions of Betaproteobacteria and Cyanobacteria (Nostocophicidae, Oscillatoriophycideae).

Figure 6.

Distribution of 97% clustered OTUs aligned and assigned to known bacterial species. Values are the relative abundance of the taxa in percentage of total sequences and figure shows taxa with >0.01% abundance. It is important to note that values are rounded to one digit; therefore, the abundance of a taxon with a value of 0.0 in one sample can range between 0.00 and 0.04%. A full OTU table can be found in the SI.

Figure 7.

Principal component analysis of bacterial species revealing taxonomic distance between sampling sites and species causing separation. Samples collected in 2012 and 2014 cluster together due to a higher relative abundance of Bacteriodetes (Sphingobacteria, Saprospirae), whereas samples collected in 2013 contain higher proportions of Betaproteobacteria and Cyanobacteria (Nostocophicidae, Oscillatoriophycideae).

Archaea were detected in most snow samples. For samples collected in 2013 and 2014 ~ 80% of all sequences could not be assigned to archaeal species after passing the QIIME quality pipeline and were removed from the analysis. Samples with only very few sequences left (n < 10) were completely removed from the analysis and only six samples were further analyzed. For samples collected in 2014 and sequenced on a #316v2 chip (see Methods), we gained 114,182 raw sequences and 89,694 sequences passed the QIIME quality pipeline. For both sequencing runs and independent from the large variation in sequence numbers, the most striking feature is that the archaeal species diversity is very low and dominated by 1–2 species only. The dominant phyla (>98% of all sequences) on most glaciers (Laugafell, Vatnajökull, Langjökull, Snaefellsjökull) belong to the Nitrososphaerales (Thaumarchaeota). Only on Hofsjökull (ICE-12_6/7) Methanosarcinales (Euryarchaeota) were found in higher abundance (71.6%) than Nitrososphaerales, and in one of the 2014 Eyafjallajökull samples (ICE-14_2) the Cenarchaeales (Thaumarchaeota) were found to make up 18.1% of the abundance besides the dominant Nitrososphaerales.

Discussion

Microbial diversity

To our knowledge, this is the first time that microbial diversity in general and snow algae in particular have been described on Icelandic glaciers and ice caps.

Eukaryotic communities

Snow algae were present and abundant on all studied glaciers and ice caps. The algal species diversity was in all cases very low and only four phylotypes with highest sequence similiarity to Chloromonas polyptera, Raphidonema sempervirens, and two uncultured Chlamydomonadaceae comprised >95% of the total sequences in all our samples. This is in agreement with Leya (2004) who also described low algal diversity, with 2–3 species making up >95% of the snow algal community, on glaciers from Svalbard. It is worth noting however, that all available 18S rRNA gene data targeting snow algae are based on culture-dependent studies and clone libraries entailing a high degree of bias and a limited sequencing depth, respectively. Therefore, a direct comparison with the few previous studies that targeted snow algae communities (e.g., Leya et al., 2004; Remias et al., 2013) is difficult although all suggest low diversity. Furthermore, it is also well-known that snow algae can dramatically change their morphologies during their life cycles (Müller et al., 2001). This makes classifications and inter-study comparisons based on microscopy very challenging and over the course of the last decades many snow algal species have been re-classified in some cases even several times (personal communication from Dr. Thomas Leya). For this reason, the most notable snow algal taxon Chlamydomonas nivalis needs to be treated as a collective taxon and not as a single species (Leya et al., 2004).

The most dominant species in our samples, Chloromonas polyptera has so far only been described from coastal Antarctic snow fields in the vicinity of penguin rockeries where this species has been identified based on microscopy and clone library sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene (Remias et al., 2013). This taxon is known to share many cryophilic strategies with the more famous snow algae species Chloromonas nivalis (Remias et al., 2013). These strategies include the formation of cyst stages and accumulation of the protective carotenoid astaxanthin. The two uncultured Chlamydomonadaceae species (labeled as Chlamydomonadaceae 1 and Chlamydomonadaceae 2 in Figure 4) are abundant in the Alps and are also known for the formation of cyst stages (personal communication Thomas Leya). However, not much is known about their physiology, since culturing efforts have not been successful so far. Based on their 18S rRNA they show the highest sequence similarity (89–93% similarity) with other Chloromonas species found in our samples (Figure S2).

The second most abundant species Raphidonema sempervirens (Figure 4) is better known as a typical permafrost algae and is not a true snow algae species. Laboratory experiments (Leya et al., 2009) also demonstrated that Raphidonema sempervirens does not share one of the main cryophilic properties of true snow algae, i.e., the production of secondary carotenoids (e.g., astaxanthin). Yet, in culture and under optimal conditions Raphidonema sempervirens is able to produce significant amounts of primary carotenoids (xanthophylls; Leya et al., 2009). In our samples, we only detected relatively minor amounts of the xanthophylls violaxantin and lutein (Table 4) besides chlorophyll and the secondary carotenoid astaxantin. However, analyses of natural snow algae samples revealed that pigment distributions are most often highly variable and dependent on sampling time and location. For example, in Lutz et al. (2014) we have shown that the pigment composition on a single glacier dramatically changed during a 2 week melting season. Furthermore, Stibal and Elster (2005) have suggested that Raphidonema sempervirens is likely introduced onto glacial surfaces by wind rather than through in-situ propagation. Thus, despite its high abundance in some of our samples (e.g., 93.3% in Hofsjökull in 2012 and 90.9–98.5% in Eyafjallajökull in 2014) it remains unclear whether this species plays an active role in the ecology of Icelandic glaciers and elsewhere.

All samples collected early in the melt season in 2013 (except Vatnajökull) showed a much higher relative abundance of sequences assigned to Fungi (67.0–94.9% of total sequences), with the most abundant class represented by the Microbotryomycetes (Basidomycota), in comparison to Chloroplastida (4.5–29.8%). The higher relative abundance of fungi in our samples could be due to the earlier sampling time (beginning of June in 2013 compared to end of July in 2012 and end of August in 2014) and thus before the onset of melting, which initiates the bloom of snow algal communities. In contrast, samples collected in 2012 and 2014 showed a higher relative abundance of Chloroplastida (35.4–60.6%; fungi: 6.6–53.5%). They also confirmed the presence of Stramenopiles (e.g., Chrysophyceae; Eyafjallajökull 2014 samples), Rhizaria (e.g., Cercozoa; Drangajökull and Hofsjökull 2012 samples) and Alveolata (e.g., Ciliophora; Laugafell and Eyafjallajökull in 2014), which were only found in considerable abundances where snow algal sequences were also abundant. Their presence may support the importance of snow algal communities as primary colonizers, producers of organic carbon and nutrient sources for other microbial communities.

Bacterial communities

A comparison with previous bacterial studies of snow is easier since more 16S rRNA gene studies have been published so far. However, these mostly targeted relatively fresh spring snow (Larose et al., 2010) or clean summer snow (Cameron et al., 2014). In our study, we targeted bacteria in summer snow that were associated with snow algal communities. Yet, considering that algal diversity is limited to very few taxa, we could not find a match between bacterial and algal species composition (Figures 5, 7). Likewise for algae, bacterial species compositions from samples collected late in the melt season (August 2012 and 2014) compared to early in the season (June 2013) suggest a likely seasonal effect. Specifically, Betaproteobacteria were more abundant in sequence data from earlier in the melt season (2013 samples) whereas Bacteroidetes were more abundant later in the season (2012 and 2014 samples). In other studies a high relative abundance of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes has often been found in snow and ice samples not associated with algal blooms. For example, a high abundance of Proteobacteria was found in snow in Greenland (Cameron et al., 2014), in snow and ice in China (Segawa et al., 2014), in spring snow in Svalbard (Larose et al., 2010), in snow, slush and surface ice in Svalbard (Hell et al., 2013), and in cryoconite holes in the Alps and Svalbard (Edwards et al., 2013, 2014). Furthermore, in previous studies Bacteroidetes also showed a higher relative abundance in cryoconite holes (Edwards et al., 2013, 2014).

Archaeal communities

We were also able to confirm the presence of archaea in our samples. Currently, only very few studies have documented the presence of archaea in glacial environments. They have been found in a glacial stream in Austria (Battin et al., 2001), in subglacial sediments in Canada (Boyd et al., 2011) and in cryoconite holes in Antarctica (Cameron et al., 2012) and Svalbard (Zarsky et al., 2013). Our study revealed a very limited diversity, with Nitrososphaerales (Thaumarchaeota) and Methanosarcinales (Euryarchaeota) being the only archaeal taxa present (Table 7), consistent with the earlier studies. Cameron et al. (2012) similarly found a limited number of taxa affiliated with Thaumarchaeaota and Methanobacteriaceae restricted to Antarctic cryoconite. Cameron et al. (2014) reported similar low archaeal diversity in four snow samples collected between 1.6 and 9.5 km from the margin of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Therefore, when taken into consideration jointly, these studies offer a consensus that the apparent diversity of Archaea on glacier surfaces is low. Nitrososphaerales may play an important role in nitrogen cycling contributing toward ammonia oxidation and nitrification (Tourna et al., 2011; Zarsky et al., 2013; Stieglmeier et al., 2014). However, in order to fully explore such links further detailed analyses are needed.

Table 7.

Distribution of 97% clustered OTUs aligned and assigned to archaea in analyzed red snow samples, revealing a dominance of the two phyla Nitrososphaerales (Thaumarchaeota) and Methanosarcinales (Euryarchaeota).

| Taxon | Laugafell | Hofsjökull | Vatnajökull | Langjökull | Langjökull | Snaefellsjökull | Eyafjallajökull | Eyafjallajökull | Eyafjallajökull |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE-12 4/5 | ICE-12 6/7 | ICE-13 11–15 | ICE-13 16–18 | ICE-13 19 | ICE-13 21–24 | ICE-14 1 | ICE-14 2 | ICE-14 3 | |

| Crenarchaeota; MBGA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Crenarchaeota; Thaumarchaeota; Cenarchaeales; Cenarchaeaceae |

2.8 | 0.7 | 7.7 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Crenarchaeota; Thaumarchaeota; Cenarchaeales; SAGMA-X |

0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.1 | 0.0 |

| Crenarchaeota; Thaumarchaeota; Nitrososphaerales; Nitrososphaeraceae |

96.5 | 27.6 | 92.0 | 99.7 | 98.1 | 95.6 | 100.0 | 78.6 | 99.9 |

| Euryarchaeota; Methanobacteria; Methanobacteriales; MSBL1 |

0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Euryarchaeota; Methanomicrobia; Methanosarcinales; Methanosarcinaceae |

0.0 | 71.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 0.0 |

It is important to note that values are rounded to one digit; therefore, the abundance of a taxon with a value of 0.0 in one sample can range between 0.00 and 0.04%.

Environmental parameters

In order to investigate the environmental parameters controlling snow algal species distribution we analyzed a large suite of physical and chemical parameters in all collected snow samples. We quantified aqueous nutrient and trace metal contents as well as particulate nutrient abundances. Our geochemical modeling (Table S7) showed that nutrients and trace metals varied over a narrow range, and were in equilibrium with the nutrient-rich and fast dissolving ubiquitously present volcanic ash (Dagsson-Waldhauserova et al., 2015) which likely supports snow algal communities to thrive. However, we could not establish any relevant differences between sites of red and clean snow. Spijkerman et al. (2012) also could not find a relation between dissolved and particulate nutrients in red snow samples in Svalbard.

Nitrogen is often the most important nutrient for microbial growth. Particulate d15N results showed throughout negative values ranging from −11.2 to −3.9‰ suggesting an atmospheric nitrogen source for all samples. This indicates that the source of nitrogen is very similar for all glaciers and not a selecting factor for snow algal and bacterial distribution. Other studies have identified fecal pellets from bird colonies as the main primary source, which would lead to more recycled nitrogen and thus more positive nitrogen isotopic values (Fujii et al., 2010). Analysis of the particulate carbon to nitrogen ratios (C/N) revealed nitrogen limiting conditions (C/N > 6.6, Redfield ratio) for Langjökull, Snaefellsjökull and Eyafjallajökull and non-limiting conditions (C/N < 6.6) for Hofsjökull, Mýrdalsjökull and Vatnajökull. Although in this study particulate carbon was analyzed as total carbon (TC), the largest proportion is likely to be organic carbon since no carbonates were found in the XRD analysis and overall carbonates are highly unlikely in basaltic rocks. Nevertheless, overall the total carbon and nitrogen contents and C/N ratios in our solid samples are similar to most values measured in other glacial communities such as snow algae in Svalbard (C/N: 16–33; Spijkerman et al., 2012), cryoconite holes on a Himalayan Glacier (C: 2.7%, N: 0.27%, C/N: 10; Takeuchi et al., 2001) and in cryoconite holes in Svalbard (C: up to 4%, N: up to 0.4%, C/N 12.5; Stibal et al., 2006).

We could not identify patterns for any of the analyzed environmental parameters to explain differences in species composition between glaciers. However, we may not have captured all parameters and there may be trends for overall biomass. Furthermore, the extend of melting and stage in the melt season at the time of collection may play a more important role and needs to be investigated in future studies.

Metabolic inventory

Snow algae have evolved a well-adapted physiology and metabolism in order to thrive in glacial environments (Remias et al., 2005; Leya et al., 2009). Fatty acids play an essential role as structural elements of their membranes and as storage compounds (Thompson, 1996). The relative composition of fatty acids depends on environmental factors such as temperature, irradiation and nutrient availability (Piorreck et al., 1984; Roessler, 1990), but also varies between species (Spijkerman et al., 2012). In our samples we found mainly the two common saturated C16 and C18 fatty acids, but also unsaturated C16 and C18 compounds. Temperature is one of the main factors that affect the fatty acid composition, with a general trend toward increasing unsaturation with decreasing temperatures. However, in this study, temperature effects can be neglected since measured snow temperatures varied by less than 1°C (Table 1). Therefore, we contend differences in fatty acid abundance more likely originate from varying nutrient concentrations. Piorreck et al. (1984) found a positive correlation between nitrogen concentrations and fatty acid production of lab cultures of green algae and they showed that a high production of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) occurred at high N concentrations, whereas at lower concentrations there was a shift toward a higher relative abundance of C16:0 and C18:1. Spijkerman et al. (2012) also reported an increase in C18:1 production of lab cultures with decreasing nitrogen concentrations. One explanation may be a metabolism shifted toward nitrogen free non-protein compounds with nitrogen deficiencies.

Fatty acids are also often linked to pigments and astaxanthin has been shown to be associated with higher amounts of C18:1 fatty acids (Řezanka et al., 2008). The same trend could be found in our samples with higher astaxanthin contents in samples collected in 2012 toward the end of the melt season and also the highest relative abundance of C18:1. Astaxanthin is one of the main pigments causing an intensive red coloration of snow algal cells. Samples collected in 2012 showed overall more red pigmentation, potentially due to the collection date being toward the end of the melt season and longer exposure periods to stress (e.g., irradiation), whereas in 2013 samples were collected earlier in the season and showed more green and yellow pigmented cells (see Figure 2 and Table 4). Astaxanthin was primarily found in samples collected in the 2012 and 2014 field campaigns, which were carried out later in the melt season after longer periods of higher irradiation. This also matches our findings in Greenland where we followed pigment development over a three-week period and found increasing amounts of astaxanthin while the melting progressed (Lutz et al., 2014). In their samples from Antarctica, Remias et al. (2013) found much higher secondary carotenoid contents (51%) for Chloromonas polyptera, which was also one of the dominant species in our study. The lower secondary carotenoid content in our samples that were dominated by Chloromonas polyptera could be due to lower stress levels in Iceland (e.g., less excessive irradiation) or the high content of Raphidonema sempervirens contributing to the total pigment content and which is not known to produce these pigments (Leya et al., 2009). It is important to mention that a contribution of pigmentation derived from Embryophyta (mainly Chl a) to the total analyzed pigment composition cannot be excluded.

The pigmentation may also be linked to the observed decrease in albedo from clean snow (76% ± 8) to sites where we observed algal colonization (56% ± 14). In Iceland, the most common considered component of albedo change is the volcanic ash and the combination of black ash and colored algae affect albedo measurements dramatically. A quantitative evaluation of the algal contribution to the observed decrease in albedo is still lacking and needs to be further investigated. However, the observed reduction in albedo at our algal sampling sites (Table 1) matches our previous observations in Greenland using the same approach (Lutz et al., 2014).

In conclusion, we show that snow algae are abundant on all major Icelandic glaciers and ice caps with a rich community comprising of other micro-eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea. Snow algal pigmentation and volcanic ash are causing a reduction of surface albedo, which in turn could potentially have an impact on the melt rates of Icelandic glaciers.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Susan Girdwood (Aberystwyth University), Dr Christy Waterfall and Ms Jane Coghill (University of Bristol) for help with the DNA sequencing, Dr Rob Newton (University of Leeds) for support with the carbon and nitrogen analyses and Dr Fiona Gill (University of Leeds) for help with the fatty acid analysis. We would like to acknowledge Dr Anthony Stockdale (University of Leeds) for the phosphorus analysis, Neil Bramall (University of Sheffield) for the ICP-MS analysis and Dr Alan Tappin (Plymouth University) for the DOC analysis. Dr Juan Diego Rodriguez-Blanco from the Nano-Science Centre (University of Copenhagen) is thanked for his help with the PHREEQC modeling. This work was funded by a University of Leeds grant to SL and LGB, by the Dudley Stamp Memorial Award from the Royal Geographical Society and the President's Fund for Research Visit grant from the Society for General Microbiology granted to SL, the NE/J02399X/1 grant to AMA and the NE/K000942/1 grant to AE. The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their comments that helped to improve the manuscript.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00307/abstract

References

- Anesio A. M., Laybourn-Parry J. (2012). Glaciers and ice sheets as a biome. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 219–225. 10.1016/j.tree.2011.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battin T. J., Wille A., Sattler B., Psenner R. (2001). Phylogenetic and functional heterogeneity of sediment biofilms along environmental gradients in a glacial stream. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 799–807. 10.1128/AEM.67.2.799-807.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning L. G., Anesio A. M., Lutz S., Tranter M. (2014). Biological impact on Greenland's albedo. Nat. Geosci. 7, 691–691 10.1038/ngeo2260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd E. S., Lange R. K., Mitchell A. C., Havig J. R., Hamilton T. L., Lafrenière M. J., et al. (2011). Diversity, abundance, and potential activity of nitrifying and nitrate-reducing microbial assemblages in a subglacial ecosystem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4778–4787. 10.1128/AEM.00376-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron K. A., Hagedorn B., Dieser M., Christner B. C., Choquette K., Sletten R., et al. (2014). Diversity and potential sources of microbiota associated with snow on western portions of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 594–609. 10.1111/1462-2920.12446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron K. A., Hodson A. J., Osborn A. M. (2012). Structure and diversity of bacterial, eukaryotic and archaeal communities in glacial cryoconite holes from the Arctic and the Antarctic. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 82, 254–267. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., Costello E. K., et al. (2010). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336. 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung M. K., Au C. H., Chu K. H., Kwan H. S., Wong C. K. (2010). Composition and genetic diversity of picoeukaryotes in subtropical coastal waters as revealed by 454 pyrosequencing. ISME J. 4, 1053–1059. 10.1038/ismej.2010.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagsson-Waldhauserova P., Arnalds O., Olafsson H., Hladil J., Skala R., Navratil T., et al. (2015). Snow–Dust Storm: Unique case study from Iceland, March 6–7, 2013. Aeolian Res. 16, 69–74 10.1016/j.aeolia.2014.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis T. Z., Hugenholtz P., Larsen N., Rojas M., Brodie E. L., Keller K., et al. (2006). Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–5072. 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A., Mur L. A., Girdwood S. E., Anesio A. M., Stibal M., Rassner S. M., et al. (2014). Coupled cryoconite ecosystem structure–function relationships are revealed by comparing bacterial communities in alpine and Arctic glaciers. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 89, 222–237. 10.1111/1574-6941.12283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A., Pachebat J. A., Swain M., Hegarty M., Hodson A. J., Irvine-Fynn T. D., et al. (2013). A metagenomic snapshot of taxonomic and functional diversity in an alpine glacier cryoconite ecosystem. Environ. Res. Lett. 8:035003 10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/035003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii M., Takano Y., Kojima H., Hoshino T., Tanaka R., Fukui M. (2010). Microbial community structure, pigment composition, and nitrogen source of red snow in Antarctica. Microb. Ecol. 59, 466–475. 10.1007/s00248-009-9594-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentz-Werner P. (2007). Roter Schnee: oder Die Suche nach dem Färbenden Prinzip. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Gislason S. R., Oelkers E. H. (2003). Mechanism, rates, and consequences of basaltic glass dissolution: II. An experimental study of the dissolution rates of basaltic glass as a function of pH and temperature. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 3817–3832 10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00176-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guðmundsson S., Björnsson H., Pálsson F., Haraldsson H. (2005). Energy balance calculations of Brúarjökull during the August 2004 floods in Jökla, N-Vatnajökull, Iceland. Reyljavik: Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Ø., Harper D. A. T., Ryan P. D. (2012). PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Paleontol. Electron 4, 9 Available online at: http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/past.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hell K., Edwards A., Zarsky J., Podmirseg S. M., Girdwood S., Pachebat J. A., et al. (2013). The dynamic bacterial communities of a melting High Arctic glacier snowpack. ISME J. 7, 1814–1826. 10.1038/ismej.2013.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodson A., Anesio A. M., Tranter M., Fountain A., Osborn M., Priscu J., et al. (2008). Glacial ecosystems. Ecol. Monogr. 78, 41–67 10.1890/07-0187.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson S. P., Jónasson K., Sigurdsson I. A. (2008). The three igneous rock series of Iceland. Jökull 58, 117–138 Available online at: http://www.nattsud.is/skrar/file/Jokull58.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. T., Gislason S. R. (2008). Rapid releases of metal salts and nutrients following the deposition of volcanic ash into aqueous environments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 3661–3680 10.1016/j.gca.2008.05.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larose C., Berger S., Ferrari C., Navarro E., Dommergue A., Schneider D., et al. (2010). Microbial sequences retrieved from environmental samples from seasonal Arctic snow and meltwater from Svalbard, Norway. Extremophiles 14, 205–212. 10.1007/s00792-009-0299-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leya T. (2004). Feldstudien und Genetische Untersuchungen zur Kryophilie der Schneealgen Nordwestspitzbergens. Aachen: Shaker. [Google Scholar]

- Leya T., Müller T., Ling H. U., Fuhr G. (2004). Snow algae from north-western Spitsbergen (Svalbard), in The Coastal Ecosystem of Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Synopsis of Biological Research Performed at the Koldewey Station in the Years 1991–2003, (Bremerhaven: Alfred-Wegener-Institut für Polar- und Meeresforschung (AWI-Bremerhaven)) p. 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Leya T., Rahn A., Lütz C., Remias D. (2009). Response of arctic snow and permafrost algae to high light and nitrogen stress by changes in pigment composition and applied aspects for biotechnology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 67, 432–443. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz S., Anesio A. M., Jorge Villar S. E., Benning L. G. (2014). Variations of algal communities cause darkening of a Greenland glacier. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 10.1111/1574-6941.12351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier M. F., Dyurgerov M. B., Rick U. K., O'neel S., Pfeffer W. T., Anderson R. S., et al. (2007). Glaciers dominate eustatic sea-level rise in the 21st century. Science 317, 1064–1067. 10.1126/science.1143906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller R., Möller M., Björnsson H., Guðmundsson S., Pálsson F., Oddsson B., et al. (2014). MODIS-derived albedo changes of Vatnajökull (Iceland) due to tephra deposition from the 2004 Grímsvötn eruption. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform. 26, 256–269 10.1016/j.jag.2013.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller T., Leya T., Fuhr G. (2001). Persistent snow algal fields in Spitsbergen: field observations and a hypothesis about the annual cell circulation. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 123, 42–51 10.2307/1552276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oelkers E. H., Gislason S. R. (2001). The mechanism, rates and consequences of basaltic glass dissolution: I. An experimental study of the dissolution rates of basaltic glass as a function of aqueous Al, Si and oxalic acid concentration at 25 C and pH= 3 and 11. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 3671–3681 10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00664-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst D. L. (1995). User's Guide to PHREEQC: A Computer Program for Speciation, Reaction-path, Advective-Transport, and Inverse Geochemical Calculations. Reston, VA: U.S. Department of the Interior/U.S. Geological Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Piorreck M., Baasch K.-H., Pohl P. (1984). Biomass production, total protein, chlorophylls, lipids and fatty acids of freshwater green and blue-green algae under different nitrogen regimes. Phytochemistry 23, 207–216 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)80304-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remias D., Lütz-Meindl U., Lütz C. (2005). Photosynthesis, pigments and ultrastructure of the alpine snow alga Chlamydomonas nivalis. Eur. J. Phycol. 40, 259–268 10.1080/09670260500202148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remias D., Wastian H., Lütz C., Leya T. (2013). Insights into the biology and phylogeny of Chloromonas polyptera (Chlorophyta), an alga causing orange snow in Maritime Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 25, 1–9 10.1017/S0954102013000060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Řezanka T., Nedbalová L., Sigler K., Cepák V. (2008). Identification of astaxanthin diglucoside diesters from snow alga Chlamydomonas nivalis by liquid chromatography–atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Phytochemistry 69, 479–490. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter E. (2007). Carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in volcanic soils following afforestation with native birch (Betula pubescens) and introduced larch (Larix sibirica) in Iceland. Plant Soil 295, 239–251 10.1007/s11104-007-9279-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roessler P. G. (1990). Environmental control of glycerolipid metabolism in microalgae: commercial implications and future research directions. J. Phycol. 26, 393–399 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1990.00393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K., Ooe K., Nagayama H., Makimura K. (2010). Prototheca cutis sp. nov., a newly discovered pathogen of protothecosis isolated from inflamed human skin. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60, 1236–1240. 10.1099/ijs.0.016402-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segawa T., Ishii S., Ohte N., Akiyoshi A., Yamada A., Maruyama F., et al. (2014). The nitrogen cycle in cryoconites: naturally occurring nitrification−denitrification granules on a glacier. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 3250–3262. 10.1111/1462-2920.12543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman E., Wacker A., Weithoff G., Leya T. (2012). Elemental and fatty acid composition of snow algae in Arctic habitats. Front. Microbiol. 3:380. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staines K. E., Carrivick J. L., Tweed F. S., Evans A. J., Russell A. J., Jóhannesson T., et al. (2014). A multi-dimensional analysis of proglacial landscape change at Sólheimajökull, southern Iceland. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 10.1002/esp.3662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stibal M., Elster J. (2005). Growth and morphology variation as a response to changing environmental factors in two Arctic species of Raphidonema (Trebouxiophyceae) from snow and soil. Polar Biol. 28, 558–567 10.1007/s00300-004-0709-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stibal M., Šabacká M., Kaštovská K. (2006). Microbial communities on glacier surfaces in Svalbard: impact of physical and chemical properties on abundance and structure of cyanobacteria and algae. Microb. Ecol. 52, 644–654. 10.1007/s00248-006-9083-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieglmeier M., Klingl A., Alves R. J., Simon K.-M. R., Melcher M., Leisch N., et al. (2014). Nitrososphaera viennensis sp. nov., an aerobic and mesophilic ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from soil and member of the archaeal phylum Thaumarchaeota. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64, 2738–2752. 10.1099/ijs.0.063172-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi N. (2013). Seasonal and altitudinal variations in snow algal communities on an Alaskan glacier (Gulkana glacier in the Alaska range). Environ. Res. Lett. 8:035002 10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/035002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi N., Kohshima S., Seko K. (2001). Structure, formation, and darkening process of albedo-reducing material (cryoconite) on a Himalayan glacier: a granular algal mat growing on the glacier. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 8, 115–122 10.2307/1552211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson G. A., Jr (1996). Lipids and membrane function in green algae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1302, 17–45. 10.1016/0005-2760(96)00045-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas W. H., Duval B. (1995). Sierra Nevada, California, USA, snow algae: snow albedo changes, algal-bacterial interrelationships, and ultraviolet radiation effects. Arctic Alp Res. 27, 389–399 10.2307/1552032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tourna M., Stieglmeier M., Spang A., Könneke M., Schintlmeister A., Urich T., et al. (2011). Nitrososphaera viennensis, an ammonia oxidizing archaeon from soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8420–8425. 10.1073/pnas.1013488108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yallop M. L., Anesio A. M., Perkins R. G., Cook J., Telling J., Fagan D., et al. (2012). Photophysiology and albedo-changing potential of the ice algal community on the surface of the Greenland ice sheet. ISME J. 6, 2302–2313. 10.1038/ismej.2012.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]