Coronary artery disease (CAD) and myocardial infarction (MI) are often viewed as prototypical complex genetic disorders. However, when the presentation occurs very early in life or when the disease appears to segregate in families, it may be related to one of several Mendelian disorders with CAD or MI as part of the phenotypic expression. The most useful evaluation tool at present is a definitive, carefully curated family history from the extended kindred that is likely to identify the limited number of testable genetic causes while avoiding additional testing for conditions with low pre-test probability. Here we review the potential genetic etiologies to consider when evaluating a patient with premature MI or CAD followed by recommendations for genetic testing and for consideration of referral to a center specializing in cardiovascular genetics.

Typical case

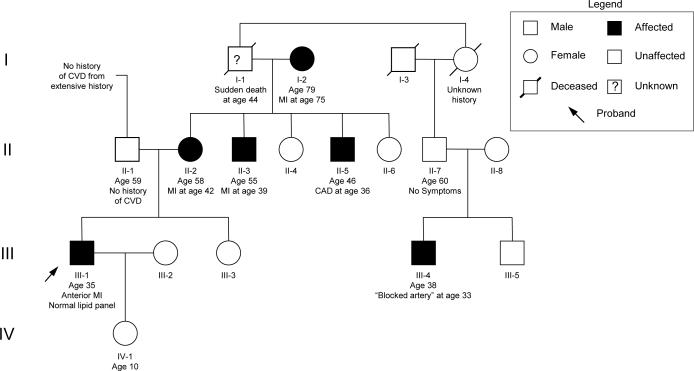

A 35 year old male presents with crescendo angina culminating in rest pain with ECG changes in the precordial leads and associated biomarker abnormalities. He has no past medical history and has no risk factors for vascular or metabolic disease. His most recent fasting lipid panel was completely normal. An initial family history is notable for ‘heart problems’ in his mother's side of the family. At coronary angiography he is found to have a 95% stenosis of his proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery which is successfully treated by percutaneous coronary intervention including a drug eluting stent. A subsequent detailed family history with objective confirmation reveals that his mother presented with an acute LAD syndrome at the age of 42 and two of her male siblings underwent coronary revascularization before the age of 40. The patient's maternal grandfather died suddenly of unknown causes at the age of 44 and a distant male cousin also had a ‘blocked artery’ at the age of 33 (see pedigree in Figure 1). An extensive investigation for known causes of premature CAD is unremarkable.

Figure 1.

Representative pedigree of a family demonstrating presumed Mendelian inheritance of MI. Squares indicate males and circles indicate females. Shaded individuals are known to be affected with MI/CAD. The arrow indicates the proband in the family. Roman numerals on the left indicate generations. Identifiers, relevant medical history, and ages are listed below individuals. CAD = coronary artery disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease; MI = myocardial infarction.

Heritability of myocardial infarction

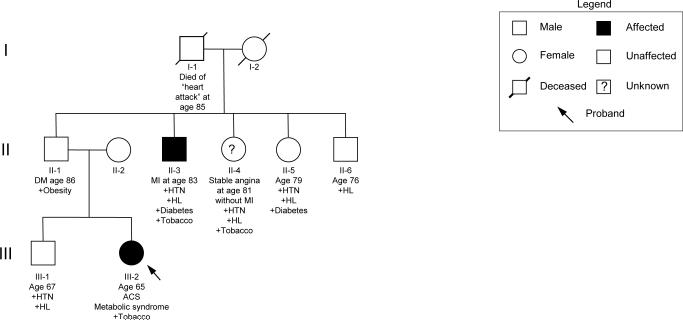

For over half a century MI has been recognized to cluster in families1 leading to a long held notion that heritable factors play a role in its development2. This clustering, however, may occur in different patterns reflecting underlying differences in the likely genetic influence particular to each family. Many individuals present with MI or CAD later in life and have multiple traditional risk factors in addition to a family history that may reveal other affected relatives. A typical pedigree reflecting this type of familial clustering is seen in Figure 2. As shown, multiple known risk factors appear in concert with MI/CAD, which itself develops later in life with different clinical presentations. While there may be genetic factors underlying the development of MI/CAD in this family (many individuals in the population sharing these risk factors will not develop MI or CAD), the presentation here is likely multifactorial (i.e. the culmination of genetic and non-genetic factors), reflecting the presence of shared genetic and environmental factors among family members. In addition, the clustering in these types of families does not typically fit a Mendelian pattern, suggesting complex inheritance (i.e. the phenotype may be under the influence of multiple causal genes), a substantial dependence on an environmental factor or factors (e.g. tobacco) or even misdiagnosis of some of the pedigree members.

Figure 2.

Representative pedigree of a family demonstrating presumed complex genetic inheritance of MI. Squares indicate males and circles indicate females. Shaded individuals are known to be affected with MI/CAD; a question mark indicates unclear disease status. The arrow indicates the proband in the family. Roman numerals on the left indicate generations. Identifiers, relevant medical history and ages are listed below individuals. ACS = acute coronary syndrome; DM = diabetes mellitus; HL = hyperlipidemia; HTN = hypertension; MI = myocardial infarction.

A different pattern of familial clustering is observed in the pedigree described in the introduction (Figure 1), with several notable features. Multiple family members are affected at a precocious age without the influence of traditional environmental risk factors, increasing the likelihood that a genetic factor of strong effect is influencing the inheritance of the trait. The specific pattern – both genders are affected from multiple generations and male-to-male transmission is observed – suggests autosomal dominant inheritance. We also see several common confounders typical of pedigrees with a strong history of MI/CAD. Phenocopies (the presence of the trait in an individual who has not inherited the causal allele) can be common given the high population prevalence of MI/CAD and the restricted biological resolution of the techniques used to diagnose MI/CAD. This is likely the case for the proband's maternal grandmother (individual I-2) who suffered an MI later in life, probably unrelated to the inherited cause in the remainder of the family. Incomplete penetrance (an individual who has inherited the causal allele but does not manifest the trait) is also common due to the long subclinical course of atherosclerosis. For example, individual II-7 appears to be a non-penetrant obligate carrier of the presumed inherited predisposition to MI/CAD given his affected son (individual III-4) and may have subclinical coronary atherosclerotic disease without manifest CAD symptoms. Incomplete history may also give the impression of incomplete penetrance (the proband's maternal grandfather, individual I-1, is probably affected however a complete history is not possible).

The overall degree to which heritable factors influence MI in the population has been estimated using epidemiologic studies. The most conceptually straightforward of these types of studies is a twin-based study in which the concordance of disease is compared between monozygotic twins (siblings sharing 100% of their genetic material) and dizygotic twins (siblings sharing 50% of their genetic material on average)3. Due to a substantial amount of environmental influence on the MI phenotype, dizygotic twins are used as a reference rather than non-twin full siblings to minimize the impact of environment on the phenotypic variance. Through various studies the heritability of MI has been estimated to be approximately 50%4-6, meaning that additive genetic variance explains roughly half of the phenotypic variability in the population. This may be an underestimate, however, due to inherent study biases and incomplete ascertainment of cases. An early age at presentation is associated with higher heritability (up to 63%)4, while certain patterns of disease are associated with lower heritability (distal coronary disease, in particular)5.

While informative from a population perspective, these heritability estimates say little about specific biology of individual cases or about the range of potential genes and genetic effect sizes that might act to generate the heritability observed in the disease7. To gain insight into an individual's risk (family members of individuals with premature MI, for example), we can turn to lessons learned through studying Mendelian disorders with MI or CAD as major or minor manifestations of the disease.

Inherited forms of premature atherosclerosis

Of the monogenic disorders with definitive evidence of MI or CAD as part of the phenotypic expression (see Table 1), many primarily affect plasma lipid levels reflecting the strong etiologic role of lipoprotein biology in the pathogenesis of MI and CAD. The most notable of these is the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), first identified by Brown and Goldstein8 as they sought to discover the genetic basis of Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH). FH, a disorder characterized by high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), tendon xanthomas, corneal arcus at a young age, and premature CAD, is caused by mutations in LDLR leading to defective cellular uptake of LDL-C. When present in a homozygous fashion (an individual who inherits two defective copies of the LDLR gene), CAD can even develop in early childhood or adolescence. As opposed to LDLR mutations, which typically exhibit incomplete dominance or co-dominance (the phenotype of the heterozygote individual is often intermediate between the two homozygote phenotypes), there are additional forms of hypercholesterolemia that exhibit true autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive patterns. Two defective copies of LDLRAP1 are needed to acquire autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia (ARH), a disorder with similar characteristics to individuals carrying LDLR mutations9. In contrast, only one gain-of-function mutation is needed in PCSK9 to cause FH310 (named this because it was the third gene discovered to cause FH after LDLR and APOB11). Sitosterolemia, a rare autosomal recessive disorder of plant sterol metabolism, presents with clinical features similar to FH including premature CAD and has been linked to mutations in both ABCG5 and ABCG8. There have been mixed results in definitively associating MI or CAD with forms of Mendelian dyslipidemias primarily affecting lipoproteins that are not processed via the LDL receptor12, 13.

Table 1.

Mendelian disorders with CAD/MI as part of the phenotypic expression

| Disorder | Associated genes | Pattern of inheritance | Association with CAD/MI | OMIM entry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autosomal Dominant hypercholesterolemia (ADH) | LDLR, APOB, PCSK9 | Autosomal dominant (however homozygote carriers can have extreme phenotype, particularly with LDLR) | Carriers at increased risk, typically related to magnitude of LDL-C level elevation | 143890, 144010, 603776 |

| Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia (ARH) | LDLRAP1 | Autosomal recessive | Similar to ADH | 603813 |

| Type III hyperlipoproteinemia (dysbetalipoproteinemia) | APOE | Autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive | Elevated plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels associated with xanthomas and premature CAD/MI | 107741 |

| Siosterolemia | ABCG5, ABCG8 | Autosomal recessive | Similar to ADH however clinical manifestations unrelated to LDL-C levels | 210250 |

| Autosomal dominant coronary artery disease 2 | LRP6 | Autosomal dominant | Metabolic syndrome and premature coronary atherosclerosis reported | 603507 |

| Familial thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection | ACTA2 | Autosomal dominant | Premature vascular disease including CAD/MI, stroke, and Moyamoya disease | 611788 |

| Homocystinuria | CBS, MTHFR | Autosomal recessive | Premature coronary atherosclerosis | 236200, 236250 |

| Familial antiphospholipid antibody syndrome | Unknown | Multifactorial | Accelerated atherosclerosis and coronary thrombosis | 107320 |

| Pseudoxanthoma elasticum | ABCC6 | Autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive | Coronary calcification and accelerated atherosclerosis | 264800 |

| Hutchison-Gilford Progeria | LMNA | Dominant (typically caused by de novo mutations) | This premature aging syndrome includes accelerated atherosclerosis | 176670 |

| Werner syndrome | RECQL2 | Autosomal recessive | Similar phenotypic presentation to Hutchison-Gilford Progeria | 277700 |

| Williams-Beuren syndrome | 7q11 deletion | Autosomal recessive | Arterial stenosis | 194050 |

| Familial Partial Lipodystrophy 1 | Unknown | Autosomal dominant | Lipodystrophy, insulin resistance and vascular disease | 608600 |

| Familial Partial Lipodystrophy 2 | 1q21 | Autosomal dominant | Lipodystrophy, insulin resistance and vascular disease | 151660 |

| Fibromuscular Dysplasia | Unknown | Autosomal dominant | Focal arteriopathy | 135580 |

There have been several attempts to find a molecular basis for apparent Mendelian forms of CAD or MI. As one might imagine, such studies are difficult and likely to be confounded by both false negative diagnoses (family members with significant subclinical CAD labeled as unaffected, for example) and phenocopies (family members with MI due to other causes – such as heavy cigarette smokers – labeled as affected, for example). The first of these studies identified MEF2A as the putative gene responsible for CAD and/or MI in a large family of 21 individuals (13 of whom were affected with CAD and/or MI)14. Linkage analysis assuming an autosomal dominant mode of transmission suggested the causal gene was located in a region containing 93 genes at chromosome 15q26. Further analysis identified a 21-base pair in-frame deletion in MEF2A that appeared to segregate with disease in this family. When additional sequencing was performed in an independent cohort, however, the same 21-bp deletion (in addition to several other mutations) in MEF2A failed to segregate with disease15, suggesting this gene does not play a causal role in CAD/MI16. Linkage analysis was successful in another family with apparent autosomal dominant inheritance of premature CAD/MI and metabolic syndrome. The investigators subsequently identified LRP6 (LDL receptor-related protein 6) as the putative causal gene17. This gene appears to be a very rare cause of CAD and metabolic syndrome.

Inherited vasculopathies

There are several inherited disorders without a primary defect in lipid metabolism but with CAD/MI as part of the clinical presentation. Williams–Beuren syndrome (also called Williams syndrome) is a rare disorder caused by a hemizygous deletion in a region of chromosome 7q11.23. Initially characterized as the combination of supravalvular aortic stenosis, mental retardation, and characteristic facies18, the phenotypic manifestations can involve multiple organ systems19. The vascular complications of Williams-Beuren syndrome typically present as stenoses in large or medium sized arteries19, however there have been reports of coronary involvement leading to premature CAD/MI20. Fibromuscular dysplasia is another vascular dysplastic disorder that can affect the coronary arteries as well as other mid-sized arteries. More common in women than in men, the disorder is often readily recognized on arteriography and can occasionally segregate as an autosomal dominant trait21. Mutations in ACTA2, known to cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections (TAAD), have also been associated with a variety of vascular disorders including premature CAD, stroke, and Moyamoya disease22.

Families with ACTA2 mutations display incomplete penetrance (only half of ACTA2 mutation carriers will develop aortic disease and other vascular complications are also incompletely penetrant) and striking phenotypic heterogeneity (one family member may exhibit aortic dissection while another develops CAD and a third develops stroke). CAD was previously reported to be associated with other vascular dysplastic syndromes including disorders on the aortic coarctation spectrum. However, more recent data does not clearly support such an association23. Heterogeneity of the underlying disorders is a significant confounder for such studies and ultimately a molecular taxonomy of vasculopathies will help to resolve these discrepancies.

In classic homocystinuria, homozygous or compound heterozygous (an individual inheriting two independent loss of function mutations in the same gene) mutations in cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) lead to defects in sulfur metabolism. These mutations, inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion, lead to mental retardation, ectopic lentis (and other Marfanoid characteristics), as well as thrombosis, including myocardial infarction24. In addition to CBS, homocysteinuria is also caused by recessive inheritance of mutations in the MTHFR gene.

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is a multisystem disorder characterized by connective tissue calcification, affecting elastic tissue in the arterial media, dermis, and Bruch's membrane in the eye25. Patients often present with pseudoxanthomas, the classic cutaneous finding of multiple small yellow-orange papules in the axilla, neck, flank, or abdomen, often described as “chicken skin.” Arterial complications can precede epidermal changes, however, and include accelerated atherosclerosis due to calcific deposition in the internal elastic lamina. Any arterial bed, including the coronary circulation, can be involved. PXE is caused by mutations in the ABCC6 gene, and has been described with both recessive and dominant patterns of inheritance26.

Inherited aneurysmal disorders

Kawasaki Disease (KD), a childhood febrile mucocutaneous syndrome27 can involve the coronary arteries, characteristically leading to coronary aneurysms. Although the majority of these will spontaneously resolve, some will persist as aneurysms while others will progress to develop coronary stenosis with or without MI28. A genetic contribution to KD is just beginning to be uncovered with the reports of several common DNA variants associated with modestly increased risk of KD29-31. There are rare reports of familial forms of KD although the genetic basis of these has been difficult to decipher in the context of a possible unidentified infectious agent. In addition, many KD cases are sporadic, rendering traditional genetic linkage analysis difficult or impossible. Coronary dissection syndromes may also present as premature MI, and even in the era of immediate coronary angiography can be missed. The evaluation of premature CAD patients, in particular young women, should include the formal consideration of underlying arterial dissection and a clinical assessment for other manifestations of the relevant vasculopathies.

Inherited coagulopathies

Several hypercoagulable states are heritable and the specter of arterial thrombosis is often raised to explain unusual presentations of myocardial infarction. Most of these conditions are not associated with CAD or MI, however. The most common heritable forms involve mutations in the genes encoding factor V (the most prevalent form of heritable thrombophilia is the factor V Leiden mutation, carried by 3-5% of the population32), antithrombin, prothrombin (including G20210A, carried by 2-3% of the population33), and proteins C and S. While carriers of these mutations have varied risk of venous thromboembolism34, these are not clearly linked to arterial thrombosis or MI33. Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), in contrast, is associated with both venous and arterial thrombosis and can present with acute MI due to coronary thrombosis. In addition, there is evidence that APS itself can accelerate the development of coronary atherosclerosis35. There is a familial form of antiphospholipid syndrome (OMIM36 107320) although the genetic basis of this form is unknown. Inherited dysfibrinogenemia along with other congenital bleeding disorders have been reported to be rare causes of arterial thrombosis and MI37.

Complex inheritance of CAD and MI

Starting with the identification of an association between a common variant on chromosome 9p21 and MI/CAD38, 39, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified over 45 loci associated with risk of MI/CAD38-45. In both case-control and prospective population-based cohort studies, increasing numbers of risk alleles are associated with increasing odds of developing disease42, 44, 46, consistent with a polygenic model of many loci each contributing a modest effect on phenotype. It is possible that families with an unusually strong clustering of MI/CAD have a large proportion of these common risk alleles but this has not been formally studied. Other complex disorders also influence risk of CAD and MI. There have been at least 157 genetic loci associated with lipid traits47 and several of these are associated with increased risk of CAD or MI48.

Approach to the patient with premature MI/CAD

As with any medical evaluation, the approach to the patient with premature MI or CAD begins with a careful history and physical examination (Table 2). Unlike most evaluations, however, in which questions regarding family history are often grouped together (i.e. “Does anyone in the family have a history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, etc?”), this evaluation should include a detailed four-generation family pedigree with specific questions focused on the mechanisms of reported events. We recognize this may be difficult to complete during an initial evaluation and suggest this can be completed over several subsequent office visits if needed. When physicians are not comfortable with pedigree analysis, “red flags” in an initial review of personal and family history could be used to trigger a referral to a specialist in cardiovascular genetics for a comprehensive evaluation. Ultimately, such evaluation should include objective support for diagnoses in family members. A careful examination of the pedigree should include an assessment of possible Mendelian inheritance patterns and a catalogue of associated phenotypes that are inherited along with MI/CAD in the family. Cataloging associated phenotypes can be critical in understanding the pattern of inheritance (and identifying individuals at risk for complications) because affected individuals can have subclinical atherosclerosis and may only manifest findings in other organ systems (i.e. peripheral vascular disease, xanthomas, etc). The physical examination should be done with particular attention to features suggestive of the disorders mentioned above. This includes assessing for stigmata of hypercholesterolemia, evidence of thromboembolic disease or peripheral vasculopathy, and pseudoxanthomas, among others. The need for additional objective testing (i.e. laboratory testing or clinical imaging directed toward a definitive diagnosis) is largely predicated on the findings from careful assessment of the family pedigree and physical examination (Table 2).

Table 2.

Objective testing in proband or definitively affected family members

| Category | Test | Indication | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical evaluation | History | Define history, risk factors, and associated phenotypes | Define age at onset, associated signs and symptoms that may suggest a genetic or environmental etiology |

| Family History | Define affected individuals to determine likely mode of inheritance. Define vital status (living or deceased), age (or age at death), age at MI/CAD, objective testing results (both affected and unaffected), and presence of risk factors | A detailed four-generation pedigree should be obtained when possible. Given a wide variety of events labeled “heart attack” by families, primary data review when possible is essential for accurate phenotyping in the kindred | |

| Physical examination | Evaluate for stigmata of Mendelian disorders such as those listed in Table 1 | When evaluating “unaffected” family members, evaluation for stigmata of peripheral vascular disease can be useful as CAD may be subclinical | |

| Laboratory evaluation | Cholesterol panel | Evaluate for hypercholesterolemia, a leading cause of premature MI/CAD. | Although a strong risk factor, almost half of premature MI cases may have normal cholesterol levels. |

| Metabolic profile, urinalysis, thyroid function | Evaluate for secondary causes of dyslipidemia | ||

| Homocysteine level | Consider with history of recurrent thrombosis | ||

| Antiphospholipid antibodies | Consider with history of recurrent thrombosis (can be both venous and arterial) | ||

| Plant sterols | Clinical suspicion of familial hypercholesterolemia with normal plasma cholesterol levels | Individuals with sitosterolemia will have elevated campesterol levels | |

| Genetic testing | Single gene testing | High clinical suspicion for a Mendelian disorder listed in Table 1 | Referral to cardiovascular genetics specialist recommended |

| Genomic sequencing in experienced center | Strong family history, minimal risk factors, and lack of definitive diagnosis based on above | Consider referral for research-based genomic sequencing |

In the same vein as objective clinical testing, the role of genetic testing is largely driven by the specific case presentation. Also similar to other objective testing, the yield of genetic testing is heavily influenced by pre-test probability. Given this, routine assessment of large genetic panels is unlikely to be helpful (for example, ordering LDLR sequencing for all patients regardless of clinical suspicion of FH is unlikely to yield meaningful answers in the majority of cases). Finally, until further studies are performed demonstrating a clinical benefit to incorporating markers identified through genome-wide association studies, current guidelines do not support the assessment of these common genetic variants49.

Referral to a specialized center focusing on cardiovascular genetics should be considered for assistance with diagnosis, interpretation of genetic testing results, risk assessment of unaffected individuals, and consideration of research-based genetic studies. Although hypercholesterolemia is strongly associated with premature MI, nearly half of premature MI cases may have normal plasma cholesterol levels50, reflecting the likely potential of genetic etiologies other than FH. Families with a clustering of disease, particularly kindreds in which MI/CAD presents at an early age, in multiple individuals, and with minimal traditional risk factors, should be strongly considered for referral to specific centers routinely performing research- or clinically-based exome or genome sequencing. While genomic sequencing may not result in immediate clinical impact for families with apparent Mendelian inheritance of MI/CAD, studies in kindreds such as the one presented in the introduction to this review are rich sources of potential discoveries that may impact our understanding of the genetic basis for these disorders.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: NOS is supported, in part, by a career development award from the NIH/NHLBI (K08HL114642). CAM is supported by the NIH, the Leducq Foundation, the British Heart foundation, The Burroughs Wellcome Foundation and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute. . The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Thomas CB, Cohen BH. The familial occurrence of hypertension and coronary artery disease, with observations concerning obesity and diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 1955;42:90–127. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-42-1-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White PD. Genes, the heart and destiny. N Engl J Med. 1957;256:965–969. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195705232562101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boomsma D, Busjahn A, Peltonen L. Classical twin studies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:872–882. doi: 10.1038/nrg932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nora JJ, Lortscher RH, Spangler RD, Nora AH, Kimberling WJ. Genetic--epidemiologic study of early-onset ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1980;61:503–508. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer M, Broeckel U, Holmer S, Baessler A, Hengstenberg C, Mayer B, et al. Distinct heritable patterns of angiographic coronary artery disease in families with myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;111:855–862. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155611.41961.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zdravkovic S, Wienke A, Pedersen NL, Marenberg ME, Yashin AI, De Faire U. Heritability of death from coronary heart disease: A 36-year follow-up of 20 966 Swedish twins. J Intern Med. 2002;252:247–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Visscher PM, Hill WG, Wray NR. Heritability in the genomics era--concepts and misconceptions. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:255–266. doi: 10.1038/nrg2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. doi: 10.1126/science.3513311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soutar AK, Naoumova RP. Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia. Semin Vasc Med. 2004;4:241–248. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-861491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, Allard D, Ouguerram K, Devillers M, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:154–156. doi: 10.1038/ng1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soria LF, Ludwig EH, Clarke HR, Vega GL, Grundy SM, McCarthy BJ. Association between a specific apolipoprotein b mutation and familial defective apolipoprotein b-100. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:587–591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcil M, Boucher B, Krimbou L, Solymoss BC, Davignon J, Frohlich J, et al. Severe familial HDL deficiency in french-canadian kindreds. Clinical, biochemical, and molecular characterization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1015–1024. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.8.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreibman PH, Wilson DE, Arky RA. Familial type IV hyperlipoproteinemia. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:981–985. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196910302811803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Fan C, Topol SE, Topol EJ, Wang Q. Mutation of MEF2A in an inherited disorder with features of coronary artery disease. Science. 2003;302:1578–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1088477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng L, Kavaslar N, Ustaszewska A, Doelle H, Schackwitz W, Hebert S, et al. Lack of MEF2A mutations in coronary artery disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1016–1020. doi: 10.1172/JCI24186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN. MEF2A sequence variants and coronary artery disease: A change of heart? J Clin Invest. 2005;115:831–833. doi: 10.1172/JCI200524715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mani A, Radhakrishnan J, Wang H, Mani A, Mani MA, Nelson-Williams C, et al. LRP6 mutation in a family with early coronary disease and metabolic risk factors. Science. 2007;315:1278–1282. doi: 10.1126/science.1136370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams JC, Barratt-Boyes BG, Lowe JB. Supravalvular aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1961;24:1311–1318. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.24.6.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pober BR. Williams-beuren syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:239–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0903074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conway EE, Jr., Noonan J, Marion RW, Steeg CN. Myocardial infarction leading to sudden death in the Williams syndrome: Report of three cases. J Pediatr. 1990;117:593–595. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80696-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rushton AR. The genetics of fibromuscular dysplasia. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo DC, Papke CL, Tran-Fadulu V, Regalado ES, Avidan N, Johnson RJ, et al. Mutations in smooth muscle alpha-actin (ACTA2) cause coronary artery disease, stroke, and moyamoya disease, along with thoracic aortic disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roifman I, Therrien J, Ionescu-Ittu R, Pilote L, Guo L, Kotowycz MA, et al. Coarctation of the aorta and coronary artery disease: Fact or fiction? Circulation. 2012;126:16–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.088294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mudd SH, Skovby F, Levy HL, Pettigrew KD, Wilcken B, Pyeritz RE, et al. The natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:1–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bercovitch L, Terry P. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum 2004. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:S13–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergen AA, Plomp AS, Schuurman EJ, Terry S, Breuning M, Dauwerse H, et al. Mutations in ABCC6 cause pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Nat Genet. 2000;25:228–231. doi: 10.1038/76109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasaki T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, Shigematsu I, Yanagawa H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in japan. Pediatrics. 1974;54:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato H, Sugimura T, Akagi T, Sato N, Hashino K, Maeno Y, et al. Long-term consequences of kawasaki disease. A 10- to 21-year follow-up study of 594 patients. Circulation. 1996;94:1379–1385. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onouchi Y, Gunji T, Burns JC, Shimizu C, Newburger JW, Yashiro M, et al. ITPKC functional polymorphism associated with kawasaki disease susceptibility and formation of coronary artery aneurysms. Nat Genet. 2008;40:35–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khor CC, Davila S, Breunis WB, Lee YC, Shimizu C, Wright VJ, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies FCGR2A as a susceptibility locus for Kawasaki disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1241–1246. doi: 10.1038/ng.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khor CC, Davila S, Shimizu C, Sheng S, Matsubara T, Suzuki Y, et al. Genome-wide linkage and association mapping identify susceptibility alleles in ABCC4 for Kawasaki disease. J Med Genet. 2011;48:467–472. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.086611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridker PM, Miletich JP, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Ethnic distribution of factor V leiden in 4047 men and women. Implications for venous thromboembolism screening. JAMA. 1997;277:1305–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Miletich JP. G20210A mutation in prothrombin gene and risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and venous thrombosis in a large cohort of us men. Circulation. 1999;99:999–1004. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.8.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varga EA, Kujovich JL. Management of inherited thrombophilia: Guide for genetics professionals. Clin Genet. 2012;81:7–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Mechanisms of disease: Atherosclerosis in autoimmune diseases. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:99–106. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. OMIM® . Mckusick-nathans institute of genetic medicine. Johns Hopkins University; http://www.omim.org. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Girolami A, Ruzzon E, Tezza F, Scandellari R, Vettore S, Girolami B. Arterial and venous thrombosis in rare congenital bleeding disorders: A critical review. Haemophilia. 2006;12:345–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, Gretarsdottir S, Blondal T, Jonasdottir A, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316:1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, Stewart A, Roberts R, Cox DR, et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316:1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.A genome-wide association study in europeans and south asians identifies five new loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:339–344. doi: 10.1038/ng.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, Musunuru K, Ardissino D, Mannucci PM, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, Hengstenberg C, Mangino M, Mayer B, et al. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S, Reilly MP, Assimes TL, Holm H, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–338. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deloukas P, Kanoni S, Willenborg C, Farrall M, Assimes TL, Thompson JR, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new risk loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:25–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ripatti S, Tikkanen E, Orho-Melander M, Havulinna AS, Silander K, Sharma A, et al. A multilocus genetic risk score for coronary heart disease: Case-control and prospective cohort analyses. Lancet. 2010;376:1393–1400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61267-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Global Lipids Genetics Consortium. Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1274–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kathiresan S, Melander O, Anevski D, Guiducci C, Burtt NP, Roos C, et al. Polymorphisms associated with cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1240–1249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ganesh SK, Arnett DK, Assimes TL, Basson CT, Chakravarti A, Ellinor PT, et al. Genetics and genomics for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease: Update: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2013;128:2813–2851. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437913.98912.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akosah KO, Gower E, Groon L, Rooney BL, Schaper A. Mild hypercholesterolemia and premature heart disease: Do the national criteria underestimate disease risk? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00556-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]