Highlights

-

•

We analyzed rhinovirus (HRV) illness in children at a hospital emergency department.

-

•

HRV-C was associated with lower respiratory tract illness (LRTI) compared to HRV-A.

-

•

Specific HRV-A and C genotypes were more strongly associated with LRTI.

-

•

Patients with multiple illness episodes had new HRV infections in each episode.

Abbreviations: HRV, human rhinovirus; LD-PCR, laboratory developed real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; REDCap, research electronic data capture; EntV, enterovirus; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; CT, cycle threshold

Keywords: Human rhinovirus, Emergency department, Lower respiratory tract infection, HRV-C, Genotyping

Abstract

Background

Human rhinovirus (HRV) infections are highly prevalent, genetically diverse, and associated with both mild upper respiratory tract and more severe lower tract illnesses (LRTI).

Objective

To characterize the molecular epidemiology of HRV infections in young children seeking acute medical care.

Study design

Nasal swabs collected from symptomatic children <3 years of age receiving care in the Emergency and Urgent Care Departments at Seattle Children's Hospital were analyzed by a rapid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system (FilmArray®) for multiple viruses including HRV/enterovirus. HRV-positive results were confirmed by laboratory-developed real-time reverse transcription PCR (LD-PCR). Clinical data were collected by chart review. A subset of samples was selected for sequencing using the 5′ noncoding region. Associations between LRTI and HRV species and genotypes were estimated using logistic regression analysis.

Results

Of 595 samples with HRV/enterovirus detected by FilmArray, 474 (80%) were confirmed as HRV by LD-PCR. 211 (96%) of 218 selected samples were sequenced; HRV species A, B, and C were identified in 133 (63%), 6 (3%), and 72 (34%), respectively. LRTI was more common in HRV-C than HRV-A illness episodes (adjusted OR [95% CI] 2.35[1.03–5.35). Specific HRV-A and HRV-C genotypes detected in multiple patients were associated with a greater proportion of LRTI episodes. In 18 patients with >1 HRV-positive illness episodes, a distinct genotype was detected in each.

Conclusion

Diverse HRV genotypes circulated among symptomatic children during the study period. We found an association between HRV-C infections and LRTI in this patient population and evidence of association between specific HRV genotypes and LRTI.

1. Introduction

Human rhinoviruses (HRVs) are the most common cause of respiratory illness in children, accounting for up to half of acute upper respiratory tract infections [1], [2], [3]. HRV has been historically considered to be a minor pathogen, but with the development of sensitive molecular diagnostics, the virus has been increasingly associated with severe respiratory disease, particularly in children [4], [5]. In hospital and community settings, HRV has been linked to lower respiratory tract illness (LRTI), wheezing, acute asthma, and death in children [6], [7], [8], [9].

HRVs are phylogenetically classified into three species: HRV-A, HRV-B, and the recently discovered HRV-C. All three species have been associated with acute respiratory illness. Although inpatient studies suggest that HRV-C may be more frequently associated with serious disease [5], [10], studies performed in outpatient settings show no clear association of HRV species with disease severity [2], [11], [12], [13]. While many HRV genotypes have been sequenced, the epidemiology and clinical significance of specific HRV genotypes are poorly characterized.

2. Objectives

This study aims to characterize the molecular epidemiology of HRV infections in children seeking acute care for respiratory symptoms in Seattle, WA, and describe the association of specific HRV species and genotypes with clinical outcomes.

3. Study design

3.1. Subjects

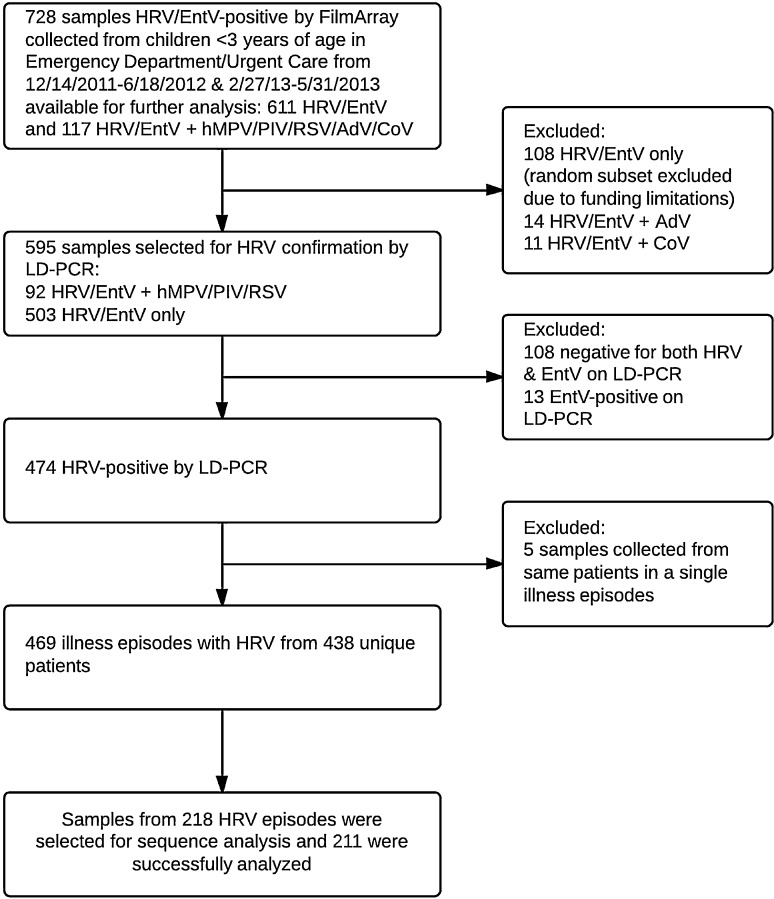

Specimens from children <3 years of age presenting with respiratory symptoms to Seattle Children's Hospital (SCH) Emergency Department (ED) or Urgent Care Clinic (UC) from December 2011 to June 2012 and February to May 2013 that were HRV positive by a laboratory-developed real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay (LD-PCR) were included in the clinical outcomes analysis (Fig. 1 ). A subset of these samples was included in the sequencing analysis. All testing and analysis were performed, retrospectively. Specimens between July 2012 and January 2013 were not available for analysis. Diagnosis, hospital admission and clinical outcome were obtained by electronic and paper chart review using Project REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [14].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of sample selection for virologic testing and chart review. Of all 757 samples collected from eligible patients during the study time period, 469 illness episodes from 438 unique patients were analyzed.

3.2. Virus detection

Nasopharyngeal samples collected with midturbinate nylon-flocked nasal swabs (Copan Diagnostics) in the ED or UC were tested for 15 respiratory viruses by FilmArray® (BioFire), a qualitative assay that does not differentiate between HRV and enterovirus (EntV) [15], [16]. The other 13 viruses detected include: adenovirus, coronavirus HKU1 and NL63, human metapneumovirus (hMPV), influenza A H1, H1 2009, and H3, influenza B, parainfluenza 1, 2, 3, and 4, and respiratory syncytial virus. Samples positive for HRV/EntV were stored normally at −70 °C, and at −20 °C during transient periods up to one month, until testing by LD-PCR for HRV. Total nucleic acids were extracted using a guanidinium lysis/isopropanol precipitation protocol [17] and amplified using the method of Lu et al. which targets the HRV 5′ noncoding region (NCR) [18]. Samples were considered HRV positive if they had a PCR cycle threshold value (CT) <40. Samples negative for HRV by HRV LD-PCR were tested for EntV by EntV LD-PCR [19].

3.3. Sequencing

Samples with HRV LD-PCR CT values ≤30 with equal representation from each month of specimen collection were randomly selected for HRV DNA sequencing. Additionally, samples from patients with multiple illness episodes were sequenced. HRV RNA was transcribed into cDNA using Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (Affymetrix) and amplified in a semi-nested PCR assay using Expand High Fidelity polymerase (Roche Molecular Systems) and primers OL-27 (CGG ACA CCC AAA GTA G) and OL-26 (GCA CTT CTG TTT CCC C) in the first PCR and OL-200 (GGC AGC CAC GCA GGC T) and OL-26 in the semi-nested PCR, which amplify an approximately 175 base-pair fragment of the HRV 5′ NCR [20]. Gel-extracted (Qiagen) amplicons were sequenced (GeneWiz) and analyzed using Sequencher 4.1 software and compared to HRV reference sequences from GenBank using the nucleotide–nucleotide BLAST algorithm (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; www.blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Trimmed sequences of 127 base-pairs were aligned using Geneious R6.1 (Biomatters) and Seaview 4.4 [21], [22]. Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed using the maximum likelihood method with 100 bootstrap replicates using PhyML 3.0 within DIVEIN [23]. Neighbor joining trees were drawn and edited using FigTree v1.4.1 [24]. Sequences were considered to be divergent genotypes if they differed from other study sequences by >2% when compared using BLAST [25]. Study sequences were not submitted to GenBank because they were shorter than the >200 bp requirement and are available upon request.

3.4. Clinical outcomes

LRTI was defined as the presence of any of the following: hospitalization due to respiratory illness, presence of crackles or wheezing on lung exam, consolidation on chest X-ray, presence of hypoxia, severe respiratory distress, or respiratory failure by physician diagnosis. URTI was defined as the presence of rhinorrhea, sore throat, nasal congestion, or secondary bacterial infection without any of the LRTI criteria.

3.5. Statistical methods

Unadjusted linear or logistic regression analyses with clustered sandwich standard errors to account for within-patient correlation were used for sample-level comparisons, while patient-level comparisons were calculated using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney nonparametric tests for continuous variables. Associations between LRTI and HRV species were estimated using unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression. Associations between LRTI and individual genotypes detected in ≥4 samples were estimated by unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression, using likelihood ratio tests to assess overall significance. Covariates in the multivariable models included age (<12 vs. ≥12 months), gender, race, underlying disease (Yes/No), premature birth (<37 weeks gestation), season (December–February vs. March–June), and coinfection. Testing was two-sided with an alpha of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp).

4. Results

4.1. Patients and HRV LD-PCR results

Of 595 samples positive for HRV/EntV by the FilmArray respiratory panel, HRV LD-PCR confirmed HRV in 474 samples (80%), representing 438 patients. EntV was detected in 13 samples (2%) (Fig. 1). Five samples were excluded from analysis because they were collected within two weeks of a prior sample and considered a repeat sample from a single illness episode. Altogether, 432 (92%) of 469 HRV-positive samples were collected in the ED and 274 (62%) patients were male.

Samples HRV/EntV-positive by FilmArray only were more likely to be coinfected with other respiratory viruses compared to samples HRV-confirmed by LD-PCR (unconfirmed vs. confirmed; 22% vs. 14%; P = 0.03). HMPV was more likely to be found in samples positive by FilmArray only (9% vs. 4%, P = 0.03). Samples HRV/EntV-positive by FilmArray only were collected from patients with a higher median age at time of first illness compared to samples HRV-confirmed (16 vs. 12 months [range 0–36 months]). There were no differences in collection season or patient gender between the HRV-confirmed and unconfirmed samples.

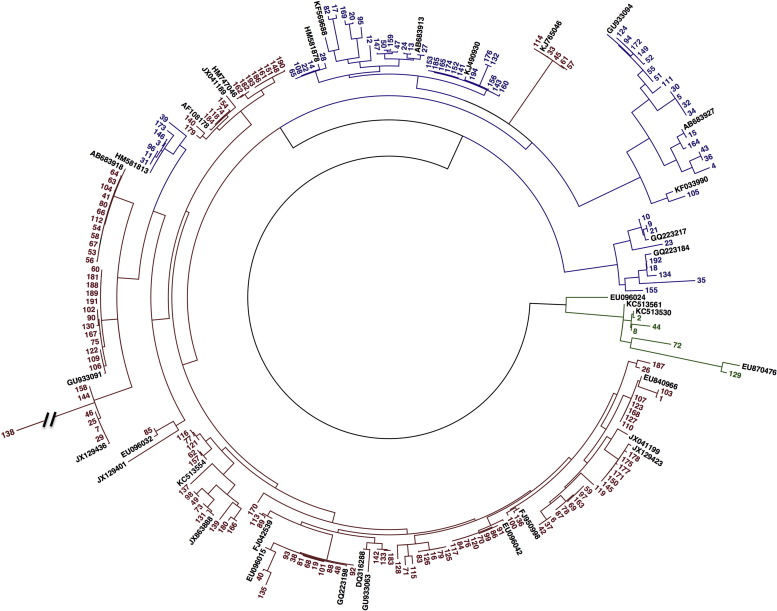

4.2. Phylogenetic analysis

Of 469 HRV-confirmed samples, 198 (42%) were selected for sequencing, and 194 of these (98%) were successfully sequenced (Fig. 2 ) along with 17 additional samples from repeat illness episodes. All sequenced samples included 133 (63%) HRV-A, 6 (3%) HRV-B, and 72 (34%) HRV-C. The median CT value of the 198 selected samples was 25 (range 15–38) compared to a median CT value of 29 (range 13–40) for non-selected samples. Median age at sample collection was lower for samples selected than for samples not selected (selected vs. non-selected; 9 months vs. 13 months, range 0–35, P = 0.04). Compared to selected samples, non-selected samples were more commonly coinfected (12% vs. 17%; P < 0.01). There was no difference in incidence of LRTI or patient gender distribution between selected and unselected samples.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis showing 194 selected HRV samples based on the 5′ NCR. Reconstruction was performed using the maximum likelihood method with 100 bootstraps using DIVEIN. Neighbor joining trees were drawn in FigTree. HRV-A is shown in red, HRV-B in green, and HRV-C in blue. The study sequences are numbered in order of collection date. The black hash mark indicates that the branch of a HRV-A genotype was shortened to make the labels readable. Study samples were compared to reference sequences found in GenBank. Reference sequences are identified in black by their GenBank accession number. (For interpretation of the references to color in this text, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

4.3. HRV-A vs. HRV-C

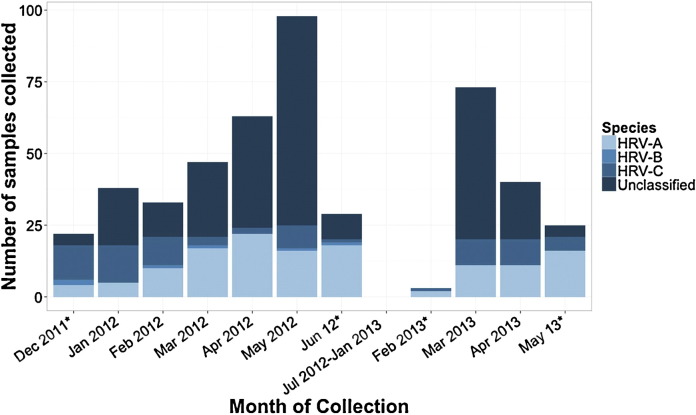

Patients with HRV-A were predominantly male compared with patients with HRV-C (73% vs. 46%). Mean CT values were similar for HRV-A and HRV-C samples. The proportion of samples collected from patients age ≥12 months was higher among HRV-C than HRV-A illness episodes (HRV-C vs. HRV-A; 56% vs. 39%, OR [95% CI]: 1.95 [1.09–3.49]) (Table 1 ). Coinfection with another respiratory virus was detected less often among HRV-C than HRV-A samples (4% vs. 14%, OR [95% CI]: 0.28 [0.08–0.98]). Fewer HRV-C specimens (n = 36; 50%) were collected during spring months (March–June) compared to 112 (84%) HRV-A samples (OR [95% CI]: 0.19 [0.10–0.37]) (Fig. 3 ). In analysis of HRV monoinfections, LRTI was more common in HRV-C than HRV-A illness episodes (75% vs. 57%; adjusted OR [95% CI]: 2.27 [1.14–4.51]).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of HRV-A vs. HRV-C illness episodes.a

| Variable | All HRV positive (n = 469)b | HRV-A (n = 133) (63%)b | HRV-C (n = 72) (34%)b | ORc | 95% CIc | P-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age ≥12 months | 239 (51) | 52 (39) | 40 (56) | 1.95 | 1.09–3.49 | 0.03 |

| Virology results | ||||||

| Coinfection | 66 (14) | 18 (14) | 3 (4) | 0.28 | 0.08–0.98 | 0.05 |

| RSV | 42 (9) | 11 (8) | 2 (3) | 0.32 | 0.07–1.48 | 0.14 |

| HMPV | 19 (4) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.61 | 0.10–6.02 | 0.67 |

| Epidemiology | 0.19 | 0.10–0.37 | <0.01 | |||

| Winter (December–February) | 96 (20) | 21 (16) | 36 (50) | |||

| Spring (March–June) | 373 (80) | 112 (84) | 36 (50) | |||

| Clinical characteristicsd | ||||||

| URTI only | 65 (35) | 49 (43) | 17 (25) | |||

| LRTI | 119 (65) | 66 (57) | 52 (75) | 2.27 | 1.14–4.51 | 0.02 |

The bold values represent significant results with P < 0.05.

HRV-B excluded due to small sample size.

Numbers are shown as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Unadjusted logistic regression accounting for within-patient correlation used to calculate values.

HRV monoinfections only were included in this analysis; All HRV positives (n = 184), HRV-A (n = 115), and HRV-C (n = 69).

Fig. 3.

Monthly distribution of 469 HRV positive nasal washes collected during the study period from December 14, 2011 to May 15, 2013 separated by species (211 sequenced samples) or unclassified (257 samples not sequenced). No samples collected between June 18, 2012 and February 27, 2013 were analyzed. Months indicated by asterisks do not represent a full month of sample collection.

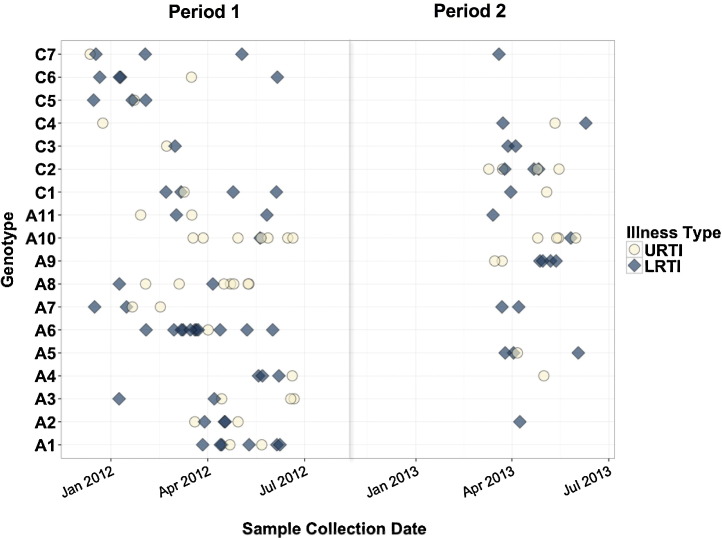

Seventy-four distinct HRV genotypes were identified among 194 selected samples. Nineteen genotypes were detected 2–4 times, 11 genotypes detected 5–9 times, and two genotypes detected ≥10 times. Among the 74 genotypes identified, 11 of 43 HRV-A genotypes and seven of 30 HRV-C genotypes were detected in ≥4 patients (Table 2 ). Fig. 4 shows the sample collection date and illness associated with each of the 18 HRV genotypes. Adjusted logistic regression models comparing the proportion of LRTI episodes for each genotype to the one with the lowest percentage of LRTI episodes (A10, 15% LRTI) suggests that specific genotypes may be associated with LRTI (Table 2; P = 0.04 likelihood ratio test).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of HRV genotypes detected in multiple patients.

| Genotype | No. episodes | No. URTI only | No. LRTI | Odds ratio (95% CI)* | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 25.9 (2.2–301) | 0.01 |

| A2 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 11.1 (0.8–150) | 0.07 |

| A3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4.5 (0.4–56) | 0.24 |

| A4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 9.2 (0.7–127) | 0.10 |

| A5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8.9 (0.3–298) | 0.22 |

| A6 | 12 | 1 | 11 | 76.7 (5.0–1173) | <0.01 |

| A7 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 14.5 (1.0–214) | 0.05 |

| A8 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 1.7 (0.1–19) | 0.67 |

| A9 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 26.8 (2.0–366) | 0.01 |

| A10 | 13 | 11 | 2 | – | – |

| A11 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 14.7 (0.9–248) | 0.06 |

| C1 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 16.2 (1.5–175) | 0.02 |

| C2 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 49.0 (2.7–875) | 0.01 |

| C3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 31.1 (1.1–914) | 0.05 |

| C4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 16.3 (1.0–265) | 0.05 |

| C5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 28.7 (1.0–830) | 0.05 |

| C6 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 29.2 (1.4–620) | 0.03 |

| C7 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 10.2 (0.7–159) | 0.10 |

Bold values represent significant results with P < 0.05.

Adjusted for age ≥12 mos, male sex, race, underlying disease, premature birth, season, coinfection.

Fig. 4.

Collection dates and clinical outcomes of HRV genotypes collected four or more times during the study period. Genotypes A1-11 are HRV-A and genotypes C1-6 are HRV-C. Blue diamonds represent patients who developed LRTI and Yellow circles represent patients who developed URTI only. Period one spanned from December 17, 2011 to June 18, 2012 and period two from March 6, 2013 to May 28, 2013. No samples were available from July 2012 to January 2013.

4.4. Multiple illness episodes

Eighteen patients had multiple HRV illness episodes; 13 had two illness episodes, four had three illness episodes, and one had four. Median time between illness episodes was 43 days (range, 16–391 days). In each patient, a different genotype was detected in each illness episode. Patients with multiple episodes were more likely to have at least one LRTI than patients with a single illness episode (83% vs. 58%; P = 0.03). Three patients with multiple episodes had no LRTIs, two had one LRTI, eight had two LRTIs, four had three LRTIs and one had four LRTIs. Patients with multiple episodes were also hospitalized more frequently for their respiratory illness compared to patients with a single illness episode (78% vs. 51%, P = 0.03). Thirty-eight (90.5%) of 42 samples from patients with >1 HRV-positive illness were sequenced. There was no difference between the HRV species distribution detected in patients with multiple illness episodes vs. patients with a single episode.

5. Discussion

Our study characterized the molecular epidemiology of HRV infections in young children in a pediatric acute care setting and examined if individual HRV species or genotypes are associated with clinical outcomes. We detected diverse HRV genotypes in our cohort, the majority of which were HRV-A and HRV-C.

HRV-C was more frequently associated with LRTI compared to HRV-A, even when adjusting for confounding factors. Previous studies in outpatient settings have shown differing results on the severity of respiratory disease produced by HRV-A vs. HRV-C. A prospective study of infants with both asymptomatic and severe HRV illness found that HRV-A and C were equally associated with severe disease [2]. However, in a study of children who presented to a pediatric ED with symptoms of wheezing, those infected with HRV-C were more like to be admitted for treatment [26]. Another prospective study demonstrated that in patients who presented at a clinic for acute care, HRV-C was associated with LRTI compared to HRV-A [13]. Similarly, our study results showed that HRV-C was more strongly associated with severe respiratory disease in children with acute illness treated in the ED or UC.

Additionally, we identified several specific HRV-A and HRV-C genotypes that were detected in multiple patients with LRTI. Many of the repeated genotypes clustered temporally, indicating that specific genotypes may emerge and spread in a seasonal pattern. While all HRV-C genotypes detected in ≥4 patients were associated with LRTI in a majority of patients, the HRV-A genotypes displayed a wider range of disease severity with a subset of HRV-A genotypes associated with LRTI in a high percentage of patients. Our findings confirm that HRV-A should not be discounted as a potential cause of severe respiratory disease in children. A previous study classified specific HRV genotypes as either mild or severe and found that both HRV-A and -C genotypes caused severe disease [2]. In a study of adults with asthma, a minor group of HRV-A was more likely to cause asthma exacerbations [27]. Our results suggest genotype may be important in determining disease severity and further analysis is warranted.

Eighteen patients, most of whom had underlying medical conditions, had multiple illness episodes separated by >14 days. A distinct HRV genotype was detected in each illness episode for each individual patient. Few studies have analyzed sequential HRV illness episodes or long-term viral shedding, particularly in children [28], [29], [30], [31]. In a prospective study of 25 infants with multiple HRV illness episodes over a 2.5-year period, four had identical virus genotypes detected in sequential episodes separated by ≥14 days and extended shedding occurred for up to 50 days [29]. Our study did not prospectively follow patients and only included children with symptomatic disease that required acute care. Potentially, some patients experienced long-term shedding, but did not exhibit symptoms that prompted them to return to our ED. Furthermore, we were unable to assess duration of asymptomatic or total viral shedding. Our findings suggest that in an acute care setting, recurrent HRV infection of a single genotype in children is uncommon.

Of 121 samples positive for HRV/EntV by FilmArray and negative for HRV by HRV LD-PCR, 13 were EntV positive by EntV LD-PCR. Degradation of low levels of HRV RNA during storage and freeze/thaw cycles could account for discordant results in the remaining samples. We were not able to assess the role of HRV viral load in the discrepant results, since the FilmArray assay does not provide viral quantitation. It is also possible that FilmArray may have a higher sensitivity to detect HRV/EntV compared to the LD-PCR assays. While two studies have found that FilmArray was more sensitive for detection of HRV than the investigators’ laboratory-developed assays, the authors of these studies did not investigate if the samples detected by FilmArray were enteroviruses [32], [33]. Another study by Renaud et al. utilizing similar methods reported in this paper, demonstrated that FilmArray had decreased sensitivity for HRV compared to HRV LD-PCR when testing non-clinical samples [16].

Our study is limited by the failure to collect samples throughout the entire year. HRV is a major pathogen in fall months and we were unable to assess the impact of HRV during this period. Studies suggest that HRV is most prevalent from fall to spring and causes more severe disease in the winter [2], [4], [5], [34]. Further, we sequenced only a subset of samples with higher viral loads. Therefore, our sequencing results do not reflect the full spectrum of strains that may be present over a year and may be biased toward strains that produce higher viral loads.

We utilized the 5′ NCR for sequencing, a region which does not unequivocally distinguish between HRV-A and HRV-C species [35]. Nevertheless, the 5′ NCR assay has been used to successfully classify HRV and provides greater sensitivity compared to the capsid region, which is prone to less efficient binding [27], [36], [37]. In our phylogenetic analysis, one group of HRV-C types fell within the HRV-A group and one group of five HRV-A types were found among the HRV-C group. This can occur when some HRV-Cs have 5′ NCRs with phylogenetic origins in HRV-A [38]. We feel that our method of sequencing the 5′ NCR was capable of uniquely typing HRV species.

This study provides important findings about the molecular epidemiology of HRV infections in pediatric patients in the acute care setting. We found that HRV-C was associated with LRTI compared to HRV-A. Specific HRV-A and HRV-C genotypes were also associated with LRTI. Patients with sequential HRV illness episodes had new infections with distinct genotypes rather than long-term shedding. Additional studies should further clarify the role of specific HRV genotypes in causing LRTI in the outpatient, acute-care setting.

Funding

All phases of this study were supported by the Seattle Children's Research Institute TRIPP Pilot Project Fund of the Center for Clinical and Translational Research (JAE & EJK) and NIH K23-AI103105 (HYC).

Competing interest

J.A.E. has received research support from Chimerix, Roche and Gilead, and serves as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline and Gilead. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

I.R.B. approval was secured from Seattle Children's Hospital.

Authors’ contributions

E.J.K., H.Y.C., and J.A.E. conceptualized and designed the study and the data collection instrument. B.S. and K.L. designed the data collection instrument and coordinated data collection. E.M. performed the virologic testing. J.K. designed the virologic assay and supervised testing. X.Q. provided the de-identified virologic samples for testing. E.M., C.J., and B.S. performed clinical data collection. M.B. performed statistical analysis. E.M., H.Y.C., and J.K. drafted the initial manuscript and all authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Support was provided by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant UL1TR000423. Clinical data collection was aided by the REDCap project, Institution of Translational Health Science grant UL1 RR025014 from NCRR/NIH and NCATS/NIH grant UL1 TR000002. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Singleton R.J., Bulkow L.R., Miernyk K., DeByle C., Pruitt L., Hummel K.B. Viral respiratory infections in hospitalized and community control children in Alaska. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1282–1290. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee W.M., Lemanske R.F., Jr., Evans M.D., Vang F., Pappas T., Gangnon R. Human rhinovirus species and season of infection determine illness severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:886–891. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0330OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacobs S.E., Lamson D.M., St George K., Walsh T.J. Human rhinoviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:135–162. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00077-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwane M.K., Prill M.M., Lu X., Miller E.K., Edwards K.M., Hall C.B. Human rhinovirus species associated with hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young US children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1702–1710. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauinger I.L., Bible J.M., Halligan E.P., Bangalore H., Tosas O., Aarons E.J. Patient characteristics and severity of human rhinovirus infections in children. J Clin Virol. 2013;58:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang Z., Gonzalez R., Xie Z., Xiao Y., Liu J., Chen L. Human rhinovirus C infections mirror those of human rhinovirus A in children with community-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Virol. 2010;49:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piotrowska Z., Vazquez M., Shapiro E.D., Weibel C., Ferguson D., Landry M.L. Rhinoviruses are a major cause of wheezing and hospitalization in children less than 2 years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:25–29. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181861da0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rueter K., Bizzintino J., Martin A.C., Zhang G., Hayden C.M., Geelhoed G.C. Symptomatic viral infection is associated with impaired response to treatment in children with acute asthma. J Pediatr. 2012;160:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hai le T., Bich V.T., Ngai le K., Diep N.T., Phuc P.H., Hung V.P. Fatal respiratory infections associated with rhinovirus outbreak, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1886–1888. doi: 10.3201/eid1811.120607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvo C., Garcia M.L., Pozo F., Reyes N., Perez-Brena P., Casas I. Role of rhinovirus C in apparently life-threatening events in infants, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1506–1508. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller E.K., Williams J.V., Gebretsadik T., Carroll K.N., Dupont W.D., Mohamed Y.A. Host and viral factors associated with severity of human rhinovirus-associated infant respiratory tract illness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:883–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreira L.P., Kamikawa J., Watanabe A.S., Carraro E., Leal E., Arruda E. Frequency of human rhinovirus species in outpatient children with acute respiratory infections at primary care level in Brazil. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:612–614. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31820d0de3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linder J.E., Kraft D.C., Mohamed Y., Lu Z., Heil L., Tollefson S. Human rhinovirus C: age, season, and lower respiratory illness over the past 3 decades. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;131:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:337–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu M., Qin X., Astion M.L., Rutledge J.C., Simpson J., Jerome K.R. Implementation of filmarray respiratory viral panel in a core laboratory improves testing turnaround time and patient care. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:118–123. doi: 10.1309/AJCPH7X3NLYZPHBW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renaud C., Crowley J., Jerome K.R., Kuypers J. Comparison of FilmArray respiratory panel and laboratory-developed real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction assays for respiratory virus detection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuypers J., Wright N., Morrow R. Evaluation of quantitative and type-specific real-time RT-PCR assays for detection of respiratory syncytial virus in respiratory specimens from children. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu X., Holloway B., Dare R.K., Kuypers J., Yagi S., Williams J.V. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for comprehensive detection of human rhinoviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:533–539. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01739-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renaud C., Kuypers J., Ficken E., Cent A., Corey L., Englund J.A. Introduction of a novel parechovirus RT-PCR clinical test in a regional medical center. J Clin Virol. 2011;51:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papadopoulos N.G., Hunter J., Sanderson G., Meyer J., Johnston S.L. Rhinovirus identification by BglI digestion of picornavirus RT-PCR amplicons. J Virol Methods. 1999;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(99)00045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., Stones-Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gouy M., Guidnodn S., Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:221–224. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng W., Maust B., Nickle D., Learn G., Liu Y., Heath L. DIVEIN: a web server to analyze phylogenies, sequence diverence, diversity, and informative sites. BioTechniques. 2010;48:405–408. doi: 10.2144/000113370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rambaut A. 2012. FigTree v1.4.1: Tree figure drawing tool. Available from http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peltola V., Waris M., Osterback R., Susi P., Ruuskanen O., Hyypiä T. Rhinovirus transmission within families with children: incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic infections. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:382–389. doi: 10.1086/525542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox D.W., Bizzintino J., Ferrari G., Khoo S.K., Zhang G., Whelan S. Human rhinovirus species C infection in young children with acute wheeze is associated with increased acute respiratory hospital admissions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1358–1364. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0498OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denlinger L.C., Sorkness R.L., Lee W.M., Evans M.D., Wolff M.J., Mathur S.K. Lower airway rhinovirus burden and the seasonal risk of asthma exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1007–1014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0585OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linsuwanon P., Payungporn S., Samransamruajkit R., Teamboonlers A., Poovorawan Y. Recurrent human rhinovirus infection in infants with refractory wheezing. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:978–980. doi: 10.3201/eid1506.081558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jartti T., Lee W.-M., Pappas T., Evans M.R.F.L., Jr., Gern J.E. Serial viral infections in infants with recurrent respiratory illnesses. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:314–320. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00161907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peltola V., Waris M., Kainulainen L., Kero J., Ruuskanen O. Virus shedding after human rhinovirus infection in children, adults and patients with hypogammaglobulinaemia. Clin Microbiol Infect: Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;19:E322–E327. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flight W.G., Bright-Thomas R.J., Tilston P., Mutton K.J., Guiver M., Webb A.K. Chronic rhinovirus infection in an adult with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:3893–3896. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01604-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loeffelholz M.J., Pong D.L., Pyles R.B., Xiong Y., Miller A.L., Bufton K.K. Comparison of the FilmArray respiratory panel and prodesse real-time PCR assays for detection of respiratory pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:4083–4088. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05010-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierce V.M., Elkan M., Leet M., McGowan K.L., Hodinka R.L. Comparison of the Idaho Technology FilmArray system to real-time PCR for detection of respiratory pathogens in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:364–371. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05996-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esposito S., Daleno C., Baggi E., Ciarmoli E., Lavizzari A., Pierro M. Circulation of different rhinovirus groups among children with lower respiratory tract infection in Kiremba, Burundi. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:3251–3256. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savolainen-Kopra C., Blomqvist S., Smura T., Roivainen M., Hovi T., Kiang D. 5′ noncoding region alone does not unequivocally determine genetic type of human rhinovirus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1278–1280. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02130-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiang D., Kalra I., Yagi S., Louie J.K., Boushey H., Boothby J. Assay for 5′ noncoding region analysis of all human rhinovirus prototype strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3736–3745. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00674-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackay I.M., Lambert S.B., Faux C.E., Arden K.E., Nissen M.D., Sloots T.P. Community-wide, contemporaneous circulation of a broad spectrum of human rhinoviruses in healthy Australian preschool-aged children during a 12-month period. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:1433–1441. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faux C.E., Arden K.E., Lambert S.B., Nissen M.D., Nolan T.M., Chang A.B. Usefulness of published PCR primers in detecting human rhinovirus infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:296–298. doi: 10.3201/eid1702.101123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]