Abstract

Rett Syndrome (RTT), a neurodevelopmental disorder that primarily affects girls, is characterized by a period of apparently normal development until 6–18 months of age, when motor and communication abilities regress. More than 95% of people with RTT have mutations in Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2), whose protein product modulates gene transcription. Surprisingly, although the disorder is caused by mutations in a single gene, disease severity in affected individuals can be quite variable. To explore the source of this phenotypic variability, we propose that specific MECP2 mutations lead to different degrees of disease severity. Using a database of 1052 participants assessed over 4940 unique visits, the largest cohort of both typical and atypical RTT patients studied to date, we examined the relationship between MECP2 mutation status and measures of growth, motor coordination, communicative abilities, respiratory function, autonomic symptoms, scoliosis, and seizures over time. In general agreement with previous studies, we found that particular mutations, such as p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, p.Arg306Cys, 3′ Truncations, and Other Point Mutations, were relatively less severe in both typical and atypical RTT. In contrast, p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, Splice Sites, Large Deletions, Insertions, and Deletions were significantly more severe. We also demonstrated that, for most mutation types, clinical severity increases with age. Furthermore, of the clinical features of RTT, ambulation, hand use, and age at onset of stereotypies are strongly linked to overall disease severity. Thus, we have confirmed that MECP2 mutation type is a strong predictor of disease severity. However, clinical severity continues to become progressively worse with advancing age regardless of initial severity. These findings will allow clinicians and families to anticipate and prepare better for the needs of individuals with RTT.

Keywords: genotype-phenotype, MeCP2, Rett syndrome, RTT

Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT; OMIM entry #312750) is an X-linked neurodevelopmental disorder affecting 1.09 per 10,000 females by the age of 12 (Laurvick 2006) and can be clinically divided into typical and atypical forms. Typical RTT is characterized by apparently normal development until 6-18 months, when acquired hand and language skills are lost and gait abnormalities and hand stereotypies begin to manifest (Neul et al. 2010). Other symptoms include respiratory dysfunction, impaired sleep, autonomic symptoms, growth retardation, small hands and feet, and a diminished pain response (Neul et al. 2010). A diagnosis of atypical RTT is given to individuals who exhibit several features of RTT, but do not exhibit all the essential clinical criteria of typical RTT. Atypical RTT represents the least and most severe forms of RTT and includes 3 named forms: preserved speech variant, early seizure variant, and congenital variant. The preserved speech variant was described by Zappella (1992) and includes mildly affected individuals who can walk, talk, and draw (Renieri 2009). In contrast, individuals with the congenital variant never acquire the ability to speak and have difficulty sitting (Ariani 2008). Thus, RTT represents a wide range of clinical presentations.

Despite this phenotypic variability, greater than 95% of cases with typical RTT and approximately 75% of cases with atypical RTT have a mutation in a single gene: methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2; Neul 2008, Percy 2007). MeCP2 binds to methylated cytosines in DNA to either activate or repress transcription (Chahrour 2008) and contains 3 functional domains: (1) a methyl-binding domain on the N-terminus allowing binding to DNA (Nan 1993), (2) a nuclear localization sequence allowing trafficking of MeCP2 to the nucleus (Nan 1996), and (3) a transcriptional repression domain, which modulates gene transcription. At present, 1013 distinct MECP2 mutations have been documented, resulting in 738 unique amino acid changes spread throughout these 3 functional domains (RettBASE: IRSF MECP2 Variation Database, http://mecp2.chw.edu.au).

Given the phenotypic variability observed in RTT, we and others have hypothesized that the degree of clinical severity is secondary to the type of MECP2 mutation. Several groups have reported genotype-phenotype correlations in RTT, and there has been consensus in recognizing that p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, p.Arg306Cys, and 3′ Truncations are less severe (Bebbington 2008, Neul 2008, Halbach 2011, Leonard 2003, and Charman 2005, Colvin 2004, Schanen 2004) and that p.Thr158Met, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, and Large Deletions are more severe (Neul 2008, Bebbington 2008, Charman 2005, Colvin 2004). On the whole, large scale analyses of other MECP2 mutation types and symptomatology has been challenging due to small participant sample sizes, variable diagnostic criteria, and the cross-sectional nature of the phenotypic data. Additionally, atypical RTT has received relatively little attention due to small participant cohorts.

In the current study, we sought to overcome some of these challenges by analyzing the largest cohort of individuals with RTT to date, divided into typical and atypical presentations, at several time points. We studied 1052 genotyped participants who were examined at 4940 different visits at tertiary care hospitals by experienced physicians all using the exact same diagnostic criteria. We found novel genotype-phenotype associations for both typical and atypical RTT, demonstrate that clinical severity increases with age for most mutation types, and show that ambulation, hand use, and age at onset of stereotypies are strongly associated with overall disease severity.

Methods

Study participants

We recruited 1052 participants who were genotyped and examined over 4940 separate visits. About ¼ of these individuals were previously analyzed and presented in a prior publication (Neul et al. 2008). Participants were examined at either the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Baylor College of Medicine, Greenwood Genetic Center, or Boston Children’s Hospital or at travel site visits attended by the same clinicians. A clinical severity score (CSS) was calculated at each visit using the following 13 criteria: age of onset of regression, somatic growth, head growth, independent sitting, ambulation (independent or assisted), hand use, scoliosis, language, non-verbal communication, respiratory dysfunction, autonomic symptoms, onset of stereotypies, and seizures, as previously described (Amir et al. 2000; Monros et al. 2001; Neul et al. 2008). Of the 1052 participants, 963 met the clinical criteria for either typical or atypical RTT.

Data management and statistics

Data were tabularized in Microsoft Excel, analyzed in SAS, and graphed in Origin 8.5.0. Clustered Poisson regression was used to estimate the association between the CSS, or the individual components of the CSS, and types of MECP2 mutations. A Poisson model was deemed appropriate given the ordinal nature of the CSS; the clustered nature of the model was necessary to account for the inclusion of multiple measurements per participant. Using this model the CSS and its individual components could be compared between subclasses both overall and within age groups. Additionally, for each subclass, the association between the CSS versus age, and separately, time was estimated. As in previous reports, corrections for multiple comparisons were not made when comparing the CSS (Bebbington et al. 2008; Perneger TV 1998). A Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons correction was applied when comparing the individual components of the CSS. For all tests, significant differences with a p < 0.05 are reported. Data are presented as average ± SD.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Our dataset included 1052 participants seen at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Baylor College of Medicine, Greenwood Genetic Center, and Boston Children’s Hospital, or the respective travel site visits, of whom 815 (77%) had a diagnosis of typical Rett Syndrome (RTT). Of those with typical RTT, average age of diagnosis was 4.1 ± 4.5 years and average age of study enrollment was 9.9 ± 8.9 years. Clinical progress was documented for these 815 participants over 4016 separate visits to the physician. Using their MECP2 mutation status, we separated the participants with typical RTT into 16 mutation groups: the 8 most common point mutations (p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg133Cys, p.Thr158Met, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, p.Arg294X, and p.Arg306Cys), 3′ Truncations, Deletions, Exon 1 Mutations, Insertions, Large Deletions, Other Point Mutations, Splice Sites, and No Mutation. Approximately 96% (786/815) of typical RTT cases had a MECP2 mutation, with 58% (473/815) of these being one of the 8 most common point mutations. Less than 1% of participants were categorized into two different mutation groups (7/815 with typical RTT); these participants were excluded from the analysis.

Atypical RTT was diagnosed in 14% (148/1052) of this patient population, having an average age of diagnosis at 5.8 ± 6.2 years. These participants were enrolled in our study on average at 9.1 ± 7.9 years of age and examined at 646 separate clinical visits. Participants meeting a diagnosis of atypical RTT were categorized into 15 MECP2 mutation groups: the 8 most common point mutations (p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg133Cys, p.Thr158Met, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, p.Arg294X, and p.Arg306Cys), 3′ Truncations, Deletions, Exon 1 Mutations, Insertions, Large Deletions, Other Point Mutations, and No Mutation. As compared to typical RTT, more participants with atypical RTT had no MECP2 mutation (24%). Less than 1% of participants with atypical RTT were classified into two mutation groups (1/148) or were male (1/148).

Clinical severity scores in typical RTT

We developed and have utilized for more than 10 years a clinical severity scale based on previously published reports (Amir et al. 2000; Monros et al. 2001; Neul et al. 2008), assessing onset of regression, growth, motor skills, communication skills, respiratory dysfunction, autonomic symptoms, and epilepsy for study participants across multiple clinic visits. Using this scale, many genotype-phenotype associations in typical RTT were observed. On the whole, mutation subclasses could be bisected into less severe MECP2 mutations and more severe MECP2 mutations. Table 1 lists the average clinical severity score (CSS) for all MECP2 mutation groups, and all significant differences between MECP2 mutation groups are presented in the matrix in Figure 1A (p < 0.05 in green cells). Mutations in p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, p.Arg306Cys, Exon 1, 3′ Truncations, and Other Point Mutations were associated with a lower CSS (Table 1 and Figure 1A). In contrast, p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, Splice Sites, Large Deletions, Insertions, and Deletions had higher scores (Table 1 and Figure 1A). Both p.Thr158Met and the No Mutations group were characterized by an intermediate disease severity. Less severe mutations on average were diagnosed later at about the age of 5 (Table 1; see p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, p.Arg306Cys, Exon 1, 3′ Truncations, and Other Point Mutations), while more severe mutations were diagnosed earlier, usually by age 3 (Table 1; see p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, Insertions, and Deletions).

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants with typical and atypical RTT.

For each diagnosis, the number of individuals (N), age at diagnosis, and clinical severity score (CSS) for each mutation group. Data is presented as average ± SD. All significant differences between CSS for typical RTT are listed in Figure 1A and for atypical RTT are listed in Figure 3.

| Typical Rett Syndrome | Atypical Rett Syndrome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | age at diagnosis | CSS | N | age at diagnosis | CSS | |

| p.Arg106Trp | 23 | 5.3 ± 4.6 | 24.5 ± 5.8 | 5 | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 25.3 ± 6.8 |

| p.Arg133Cys | 40 | 5.1 ± 4.3 | 18.0 ± 6.2 | 11 | 5.2 ± 2.1 | 13.4 ± 5.7 |

| p.Thr158Met | 91 | 3.2 ± 2.5 | 23.4 ± 6.6 | 4 | 5.9 ± 4.4 | 18.9 ± 5.9 |

| p.Arg168X | 87 | 3.4 ± 4.7 | 25.7 ± 6.7 | 5 | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 31.0 ± 3.6 |

| p.Arg255X | 81 | 3.0 ± 2.5 | 25.2 ± 6.5 | 11 | 6.8 ± 12.8 | 25.2 ± 6.8 |

| p.Arg270X | 48 | 4.0 ± 5.6 | 25.6 ± 7.9 | 6 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 26.8 ± 4.2 |

| p.Arg294X | 54 | 5.0 ± 3.5 | 19.1 ± 5.9 | 6 | 5.5 ± 2.3 | 14.0 ± 8.6 |

| p.Arg306Cys | 50 | 4.5 ± 4.9 | 19.0 ± 5.5 | 8 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 12.1 ± 7.1 |

| 3′ Truncation | 74 | 4.6 ± 4.2 | 21.3 ± 6.3 | 26 | 5.7 ± 4.3 | 16.0 ± 8.0 |

| Deletion | 47 | 3 ± 2.4 | 25.1 ± 7.0 | 2 | 2.1 ± 0 | 17.6 ± 2.8 |

| Exon 1 | 4 | 5.1 ± 4.2 | 17.0 ± 8.3 | 1 | 6.08 | 9.8 ± 4.1 |

| Insertion | 18 | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 25.2 ± 7.9 | 5 | 7.3 ± 11.0 | 33.5 ± 6.4 |

| Large Del | 74 | 4.5 ± 6.6 | 25.3 ± 6.8 | 8 | 7.3 ± 12.1 | 28.3 ± 7.6 |

| Other Point | 94 | 4.3 ± 5.3 | 21.7 ± 7.0 | 16 | 4.7 ± 2.5 | 20.1 ± 8.7 |

| Splice Sites | 8 | 4.0 ± 2.9 | 24.5 ± 5.4 | 0 | - | - |

| No Mutations | 29 | 7.2 ± 5.1 | 23.1 ± 8.8 | 35 | 7.6 ± 6.4 | 25.4 ± 7.7 |

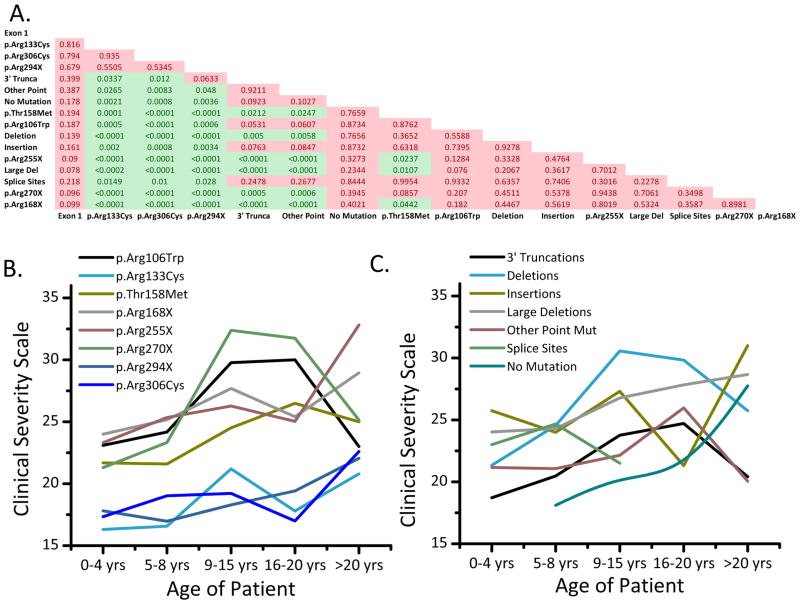

Figure 1. Clinical severity score is dependent on MECP2 mutation status in participants with typical RTT.

A) Matrix of p-values for comparisons of all MECP2 mutation groups. All significant differences (p < 0.05) are in green, and non-significant differences are in red. B-C) Clinical severity scores subdivided by age for each mutation type. The five age groups are 0–4, 5–8, 9–15, 16–20, and > 20 years.

Clinical severity score across age in typical RTT

Participants were grouped according to age (0–4 years, 5–8 years, 9–15 years, 16–20 years, and >20 years) and the associations between and within these age groups were assessed. As depicted in Figure 1B, the eight most common point mutations subdivided into 2 broad groups: a less severe group, including p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, and p.Arg306Cys, and a more severe group, including p.Arg106Trp, p.Thr158Met, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, and p.Arg270X. At 0-4 years of age, p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, and p.Arg306Cys had an average CSS of 16.8, as compared to p.Arg106Trp, p.Thr158Met, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, and p.Arg270X, which had an average CSS of 22.9. This demonstrates that less/more severe mutations begin with a less/more severe phenotype early in development. Among those >20 years of age, the average CSS increased in p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, and p.Arg306Cys to 21.8, which is approximately the clinical severity of the more severe mutations at age 0-4 years of age. p.Arg106Trp, p.Thr158Met, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, and p.Arg270X on average increased to a score of 26.6 in individuals >20 years of age. Additionally, 3′ Truncations mirrored the age-related changes of less severe point mutations, including p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, and p.Arg306Cys, while Large Deletions and Deletions were most similar to the severe point mutations (Figure 1C).

We also found a significant positive association between CSS and age in individual mutation groups. Among those with 3′ Truncation (p < 0.0001), p.Arg133Cys (p < 0.01), p.Thr158Met (p < 0.05), p.Arg168X (p < 0.001), p.Arg255X (p < 0.0001), p.Arg270X (p < 0.05), p.Arg306Cys (p < 0.001), Deletion (p < 0.01), Large Deletions (p < 0.05), and Splice Sites (p < 0.05) mutations, CSS increased across age groups (Figure 1B–C). However, we found no significant association between age and p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg294X, Insertions, Other Point Mutations, and No Mutations (p > 0.05; Figure 1B–C).

Given that individual participants were examined over multiple visits, we also examined changes in clinical severity over time. 3′ Truncation (p < 0.01), p.Arg133Cys (p < 0.01), p.Thr158Met (p < 0.05), p.Arg168X (p < 0.05), p.Arg255X (p < 0.01), p.Arg270X (p < 0.001), p.Arg306Cys (p < 0.01), and Deletion (p < 0.01) all significantly increased in clinical severity over time (Figure 1B–C). However, p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg294X, Exon 1, Insertions, Large Deletions, Other Point Mutations, Splice Sites, and No Mutations did not significantly increase over time.

Clinical features in typical RTT

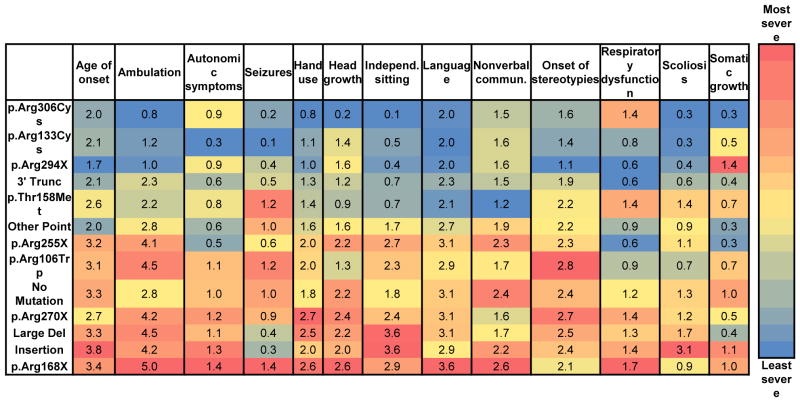

Our assessment of CSS revealed significant differences, which were dependent on MECP2 mutation type. To determine if these differences were due to one or more specific clinical features, we quantified the 13 individual components of our CSS, including age of onset, ambulation, autonomic symptoms, seizures, hand use, head growth, independent sitting, language, nonverbal communication, onset of stereotypies, respiratory dysfunction, scoliosis, and somatic growth. To study these individual components, the ordinal ratings were averaged. As tabularized in Figure 2 with a super-imposed heat map, significant differences exist between mutation groups for individual features (all significant differences are listed in Supplementary Table 1). For each column depicting a clinical feature, the cell is color coded with the least severely affected group depicted in blue, and the most severely affected group depicted in red. Age of onset is relatively later in individuals with p.Arg133Cys and No Mutation, and earlier in individuals with p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, Deletions, and Large Deletions (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, hand use is more preserved in cases with 3′ Truncations, p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, and p.Arg306Cys, as compared to p.Arg168X, p.Arg270X, and Large Deletions (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Individuals with p.Arg306Cys had significantly fewer autonomic symptoms versus p.Arg168X and p.Arg255X (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Seizures were less frequent in p.Arg306Cys cases as compared to p.Arg255X and p.Arg294X (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. Clinical features for typical RTT.

Blue is least severe and red is most severe. Scales are normalized for each clinical measure. Values represent the average score. All statistically significant differences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Of all the symptoms, ambulation paralleled the overall clinical severity score the closest. Ambulation was more conserved in 3′ Truncations, p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, and p.Arg306Cys, as compared to those with p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, and Large Deletions (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Head growth decelerated least in individuals with p.Arg294X and 3′ Truncations, and most in individuals with p.Arg270X (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Independent sitting was more likely conserved in individuals with p.Arg294X and p.Arg306Cys (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, p.Arg306Cys, and 3′ Truncations had a later onset of stereotypies, especially compared to p.Thr158Met, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, and p.Arg270X (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Scoliosis was least severe in individuals with p.Arg306Cys and most severe in individuals with p.Thr158Met, 3′ Truncations, and Large Deletions (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Body mass index was highest in the 3′ Truncation (0.7 ± 1.1) group and lowest in p.Arg294X (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 1). No statistical differences were observed between the various mutations groups in language skills, nonverbal communication, and respiratory dysfunction.

Clinical severity scores in atypical RTT

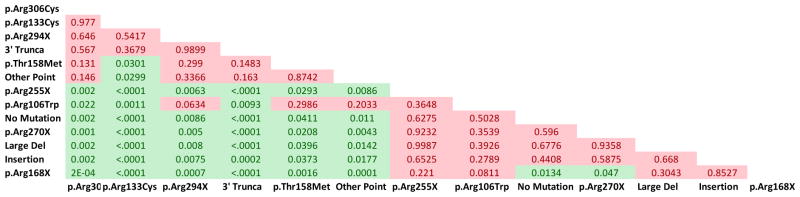

We studied 148 participants seen over 646 visits with a diagnosis of atypical RTT and found significant associations between MECP2 mutation status and phenotypic manifestation. Approximately 76% (113/148) of individuals had a MECP2 mutation, with 38% (56/148) of these occurring in one of the 8 most common point mutations. Similar to typical RTT, p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, p.Arg306Cys, and 3′ Truncations were relatively less severe as compared to p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, Insertions, Large Deletions, and No Mutations (average CSS in Table 1 and p-values in Figure 3). On the whole, relative to typical RTT, the less severe mutations were even less severe in atypical RTT, and the more severe mutations were more severe in atypical RTT (Table 1). p.Thr158Met, Deletions, and Other Point Mutations represented an intermediate disease severity group for atypical RTT.

Figure 3. Clinical severity score is dependent on MECP2 mutation status in participants with atypical RTT.

A) Matrix of p-values for comparisons of all MECP2 mutation groups. All significant differences (p < 0.05) are in green, and non-significant differences are in red.

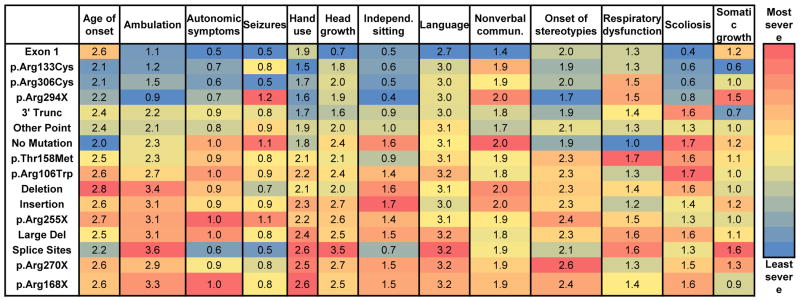

Clinical features in atypical RTT

We investigated each of the components of the clinical severity scale to determine if individual features were associated with a more or less severe clinical rating. Individuals with less severe MECP2 mutations and atypical RTT had better hand use than individuals with more severe mutations. Hand use was more preserved in p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg306Cys, and 3′ Truncations, as compared to p.Arg168X, p.Arg270X, and Large Deletions (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 2). Autonomic symptoms were fewest in 3′ Truncations and most in p.Arg168X and p.Arg270X (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 2). Less severe mutations including p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg133Cys, and p.Arg294X had a later onset of stereotypies than p.Arg270X and No Mutations (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 4. Clinical features for atypical RTT.

Blue is least severe and red is most severe. Scales are normalized for each clinical measure. Values represent the average score. All statistically significant differences are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Unlike typical RTT, language skills and nonverbal communication correlated with disease severity in atypical RTT. Language skills were more conserved in p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg306Cys, and 3′ Truncations as compared to p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, No Mutations, and Large Deletions (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 2). Nonverbal communication was significantly less affected in individuals with 3′ Truncations versus p.Arg255X and No Mutations (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

We studied typical and atypical Rett Syndrome (RTT) using the largest cohort to date and identified several novel and clinically significant associations between MECP2 mutation type and phenotypic outcomes. Our data demonstrate that MECP2 mutation type is strongly associated with phenotype in both typical and atypical RTT. Moreover, children with the less severe mutations usually begin with a relatively low clinical severity and are diagnosed later, while the opposite is true for children with more severe mutations. Importantly, we demonstrate that for most mutation types, clinical severity worsens as age increases. In both typical and atypical RTT, hand use and age at onset of stereotypies were most closely associated with overall disease severity. However, in typical RTT, ambulation and independent sitting also were associated with disease severity, while language skills were associated with disease severity in atypical RTT. We also found that growth, motor, and communication dysfunction significantly contributes to clinical severity. While these data highlight differences between MECP2 mutation types, individual participants with RTT may not follow the “average” disease course we present. Nonetheless, these findings may still be used as a predictive tool for healthcare providers and families alike.

Our investigation into atypical RTT is the first of its kind and reveals many novel genotype-phenotype correlations. On the whole, mutations that were less severe in typical RTT were even less severe in atypical RTT, while mutations that were more severe in typical RTT were even more severe in atypical RTT. Thus, atypical RTT represents the upper and lower ends of the phenotypic severity of typical RTT. As in typical RTT, p.Arg133Cys, p.Arg294X, p.Arg306Cys, and 3′ Truncations were relatively less severe, while p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, Insertions, Large Deletions, and No Mutations were severe in atypical RTT. Our analyses of atypical RTT also suggested that ambulation was more severely affected in individuals with severe mutations, but we lacked statistical power to find significant associations.

Our data corroborates several recent reports that have identified key associations between MECP2 mutation type and phenotype (Bebbington 2008, Neul 2008, Halbach 2011, Leonard 2003, Charman 2005, Colvin 2004, Glaze 2010, Jian 2007, Leonard 2003, Schanen 2004, Tarquinio 2012). Importantly, the majority of these reports have been in agreement in correlating disease severity to particular mutations. For example, p.Arg133Cys (Bebbington 2008, Neul 2008, Halbach 2011, Leonard 2003, Charman 2005), p.Arg294X (Bebbington 2008, Neul 2008, Colvin 2004), p.Arg306Cys (Bebbington 2008, Schanen 2004, Charman 2005), and 3′ Truncations (Bebbington 2008, Neul 2008) have all been identified as less severe mutations with lower clinical severities as measured by a variety of clinical severity scales. Our data confirm all of these prior findings, and also adds Other Point Mutations to this group. We also identified p.Arg106Trp, p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, p.Arg270X, Splice Sites, Large Deletions, Insertions, and Deletions as being mutations associated with a more severe disease course in typical RTT. p.Arg168X (Neul 2008), p.Arg255X (Bebbington 2008, Charman 2005), p.Arg270X (Bebbington 2008, Colvin 2004), and Large Deletions (Neul 2008) had previously been implicated as more severe mutations, and our dataset confirms this. While previous reports have concluded that p.Thr158Met is a more severe mutation (Bebbington 2008, Charman 2005), we demonstrated that as in the No Mutations group, p.Thr158Met is characterized by a disease course of intermediate severity. The latter finding is in line with a study demonstrating that the severity of p.Thr158Met and p.Arg168X is a function of the degree of X-chromosome inactivation (XCI) skewing (Archer et al 2007).

While there are strengths of the current study, including (1) the largest participant cohort studied to date, (2) repeated examination of multiple participants, (3) clinical assessment by 6 experienced physicians, and (4) use of a standardized clinical rubric, we did not investigate XCI status. XCI has been hypothesized to contribute to the phenotypic variability seen in RTT (Archer 2007, Weaving 2003) but does not solely explain the wide range in clinical severity (Bao 2008). It has also been hypothesized that XCI may skew phenotypes from typical to atypical RTT, although an analysis of XCI skewing in typical and atypical RTT participants found equal levels in both groups (Weaving, 2003). The link between XCI and RTT phenotypes is complicated by the methodology of assessment for XCI; typically, skewing of XCI is measured in circulating leukocytes. However, Gibson et al (2005) demonstrated that in a minority of cases, skewing of XCI can differ between different brain regions. For example, in an individual RTT brain, X-chromosome skewing changed from 50:50% in occipital cortex to 24:76% in temporal cortex (Gibson 2005). This demonstrates that skewing of XCI in the blood may not be a precise indicator of skewing in the brain, given that XCI skewing can vary between different regions in an individual brain.

Although using a standardized clinical rubric to calculate clinical severity provided us with internal consistency, we did not compare clinical severity scores across various scoring systems. For example Colvin et al (2003) used the Pineda, Kerr, and WeeFIM scales, and the CSS employed here, to calculate clinical severity. Our scale contains somatic growth, scoliosis, non-verbal communication, and autonomic symptoms, features which are not included in the Pineda scale (Monros et al 2001). The Kerr scale contains additional features including mood, sleep disturbances, and muscle tone, which are not included in our scale (Kerr et al 2001). Our scoring system most closely follows the Percy scale, which also includes feeding and crawling. Additionally, our scoring system includes “age of onset” and “onset of stereotypies,” measures that do not change through development, and therefore may have led to an underestimation of age-related changes in our longitudinal analyses. However, we do provide individual analyses of each of the 13 components of our clinical severity scale for both typical and atypical RTT.

Despite our large subject sample, our statistical power was limited for introducing corrections for multiple comparisons as in previous studies (Bebbington 2008, Neul 2008, Charman 2005, Schanen 2004). This represents a limitation particularly for the analyses of atypical RTT. Therefore, many of our genotype-phenotype correlations involving specific mutations or the atypical RTT group will need confirmation in a larger sample.

The importance of determining associations between MECP2 mutation type and clinical severity is at least threefold: (1) genotype-phenotype associations may reveal important molecular insight into MeCP2 protein function, (2) understanding the relationships between mutation types and clinical severity in general will enable healthcare providers to counsel individuals more robustly regarding disease prognosis, and (3) determining the average severity and variance among mutations will allow researchers conducting clinical trials to adjust their inclusion criteria and outcomes based on relative severity. From a molecular biology perspective, it is clear that MeCP2 localizes to the nucleus where it functions as a transcriptional regulator and binds to CpG islands in DNA. To do so, MeCP2 contains three functional domains: (1) a methyl-binding domain (MBD), (2) a nuclear localization signal (NLS), and (3) a transcriptional repression domain (TRD). Here we find that p.Arg106Trp, which is located in the MBD (Nan 1996), leads to a relatively severe phenotype in typical and atypical RTT. This may be secondary to deficient binding to methylated DNA, leading to aberrant transcriptional control. p.Arg168X, p.Arg255X, and p.Arg270X are all truncating mutations lacking the NLS, which is located between amino acids 255-271 (Nan 1996). Therefore, these mutations may lead to a more severe phenotype because of the inability of MeCP2 to localize to the nucleus. In contrast, p.Arg133Cys is a point mutation that may allow some MeCP2 functionality to remain intact as evidenced by the milder clinical severity. In support of this, a recent report demonstrated that while MeCP2 with p.Arg133Cys cannot bind 5-hydroxymethylcytosine to facilitate transcription, it can still bind to 5-methylcytosine to repress transcription (Mellen 2012). The p.Arg306Cys mutation both (1) inhibits the binding of nuclear receptor co-repressor (NCoR), a transcriptional repressor, to MeCP2, and (2) prevents activity-dependent phosphorylation of T308, which increases transcription {Ebert, Gabel, Robinson 2013, Lyst MJ, Ekiert R, Ebert DH, Merusi C, Nowak J, 2013}. While these interactions play an important role in transcriptional regulation, the relatively milder clinical severity of patients with p.Arg306Cys suggests that these are not the only mechanisms regulating MeCP2 function.

Perhaps most importantly, our hope is that this analysis of 815 participants with typical RTT and 148 participants with atypical RTT will serve as a tool for guidance and care of affected individuals. By exploring the unique symptomatology for individual mutations in both typical and atypical RTT, we have been able to discern genotype-phenotype connections. And while individual participants with RTT may not follow the predicted clinical course, these data nevertheless should serve as general guidance for clinicians and families.

Supplementary Material

Average numbers are given in Figure 2. Each of listed pairs is significantly different with p < 0.05 as per Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test.

Average numbers are given in Figure 4. Each of listed pairs is significantly different with p < 0.05 as per Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the RDCRC Natural History Study as well as HD061222 (NICHD), IDDRC grant HD38985 (NICHD), a Basic Research Grant (#2916) from the International Rett Syndrome Foundation to MLO, and a Civitan Emerging Scholar Award to VAC. Dr. Mary Lou Oster-Granite, Health Scientist Administrator at NICHD, provided invaluable guidance, support, and encouragement for this Rare Disease initiative.

References

- Amir RE, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome: methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 mutations and phenotype-genotype correlations. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97:147–52. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200022)97:2<147::aid-ajmg6>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer H, Evans J, Leonard H, Colvin L, Ravine D, Christodoulou J, Williamson S, Charman T, Bailey ME, Sampson J, de KN, Clarke A. Correlation between clinical severity in patients with Rett syndrome with a p.R168X or p. T158M MECP2 mutation, and the direction and degree of skewing of X-chromosome inactivation. J Med Genet. 2007;44:148–52. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariani F, Hayek G, Rondinella D, Artuso R, Mencarelli MA, Spanhol-Rosseto A, Pollazzon M, Buoni S, Spiga O, Ricciardi S, Meloni I, Longo I, Mari F, Broccoli V, Zappella M, Renieri A. FOXG1 is responsible for the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington A, Anderson A, Ravine D, Fyfe S, Pineda M, de KN, Ben-Zeev B, Yatawara N, Percy A, Kaufmann WE, Leonard H. Investigating genotype-phenotype relationships in Rett syndrome using an international data set. Neurology. 2008;70:868–75. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304752.50773.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong STC, Qin J, Zoghbi HY. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320:1224–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Neilson TC, Mash V, Archer H, Gardiner MT, Knudsen GP, McDonnell A, Perry J, Whatley SD, Bunyan DJ, Ravn K, Mount RH, Hastings RP, Hulten M, Orstavik KH, Reilly S, Cass H, Clarke A, Kerr AM, Bailey ME. Dimensional phenotypic analysis and functional categorisation of mutations reveal novel genotype-phenotype associations in Rett syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:1121–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin L, Fyfe S, Leonard S, Schiavello T, Ellaway C, de KN, Christodoulou J, Msall M, Leonard H. Describing the phenotype in Rett syndrome using a population database. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:38–43. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin L, Leonard H, de KN, Davis M, Weaving L, Williamson S, Christodoulou J. Refining the phenotype of common mutations in Rett syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004;41:25–30. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.011130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert DH, Gabel HW, Robinson ND, Kastan NR, Hu LS, Cohen S, Navarro AJ, Lyst MJ, Ekiert R, Bird AP, Greenberg ME. Activity-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2 threonine 308 regulates interaction with NCoR. Nature. 2013;499:341–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JH, Williamson SL, Arbuckle S, Christodoulou J. X chromosome inactivation patterns in brain in Rett syndrome: implications for the disease phenotype. Brain Dev. 2005;27:266–70. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaze DG, Percy AK, Skinner S, Motil KJ, Neul JL, Barrish JO, Lane JB, Geerts SP, Annese F, Graham J, McNair L, Lee HS. Epilepsy and the natural history of Rett syndrome. Neurology. 2010;74:909–12. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d6b852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbach NS, Smeets EE, van den Braak N, van Roozendaal KE, Blok RM, Schrander-Stumpel CT, Frijns JP, Maaskant MA, Curfs LM. Genotype-phenotype relationships as prognosticators in Rett syndrome should be handled with care in clinical practice. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A (2):340–50. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian L, Nagarajan L, de KN, Ravine D, Christodoulou J, Leonard H. Seizures in Rett syndrome: an overview from a one-year calendar study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11:310–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr AM, Nomura Y, Armstrong D, Anvret M, Belichenko PV, Budden S, Cass H, Christodoulou J, Clarke A, Ellaway C, d’Esposito M, Francke U, Hulten M, Julu P, Leonard H, Naidu S, Schanen C, Webb T, Engerstrom IW, Yamashita Y, Segawa M. Guidelines for reporting clinical features in cases with MECP2 mutations. Brain Dev. 2001;23:208–11. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(01)00193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurvick CL, de KN, Bower C, Christodoulou J, Ravine D, Ellaway C, Williamson S, Leonard H. Rett syndrome in Australia: a review of the epidemiology. J Pediatr. 2006;148:347–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard H, Colvin L, Christodoulou J, Schiavello T, Williamson S, Davis M, Ravine D, Fyfe S, de KN, Matsuishi T, Kondo I, Clarke A, Hackwell S, Yamashita Y. Patients with the R133C mutation: is their phenotype different from patients with Rett syndrome with other mutations? J Med Genet. 2003;40:e52. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.5.e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellen M, Ayata P, Dewell S, Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. MeCP2 binds to 5hmC enriched within active genes and accessible chromatin in the nervous system. Cell. 2012;151:1417–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monros E, Armstrong J, Aibar E, Poo P, Canos I, Pineda M. Rett syndrome in Spain: mutation analysis and clinical correlations. Brain Dev. 2001;23(Suppl 1):S251–3. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(01)00374-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X, Meehan RR, Bird A. Dissection of the methyl-CpG binding domain from the chromosomal protein MeCP2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4886–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.21.4886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X, Tate P, Li E, Bird A. DNA methylation specifies chromosomal localization of MeCP2. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:414–21. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neul JL, Fang P, Barrish J, Lane J, Caeg EB, Smith EO, Zoghbi H, Percy A, Glaze DG. Specific mutations in methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 confer different severity in Rett syndrome. Neurology. 2008;70:1313–21. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000291011.54508.aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neul JL, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, Christodoulou J, Clarke AJ, Bahi-Buisson N, Leonard H, Bailey ME, Schanen NC, Zappella M, Renieri A, Huppke P, Percy AK. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann Neurol. 2010;68:944–50. doi: 10.1002/ana.22124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percy AK, Lane JB, Childers J, Skinner S, Annese F, Barrish J, Caeg E, Glaze DG, MacLeod P. Rett syndrome: North American database. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1338–41. doi: 10.1177/0883073807308715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ. 1998;316:1236–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renieri A, Mari F, Mencarelli MA, Scala E, Ariani F, Longo I, Meloni I, Cevenini G, Pini G, Hayek G, Zappella M. Diagnostic criteria for the Zappella variant of Rett syndrome (the preserved speech variant) Brain Dev. 2009;31:208–16. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanen C, Houwink EJ, Dorrani N, Lane J, Everett R, Feng A, Cantor RM, Percy A. Phenotypic manifestations of MECP2 mutations in classical and atypical Rett syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;126A:129–40. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarquinio DC, Motil KJ, Hou W, Lee HS, Glaze DG, Skinner SA, Neul JL, Annese F, McNair L, Barrish JO, Geerts SP, Lane JB, Percy AK. Growth failure and outcome in Rett syndrome: specific growth references. Neurology. 2012;79:1653–61. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e9a70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaving LS, Williamson SL, Bennetts B, Davis M, Ellaway CJ, Leonard H, Thong MK, Delatycki M, Thompson EM, Laing N, Christodoulou J. Effects of MECP2 mutation type, location and X-inactivation in modulating Rett syndrome phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;118A:103–14. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua B, Shengling J, Fuying S, Hong P, Meirong L, Wu XR. X chromosome inactivation in Rett Syndrome and its correlations with MECP2 mutations and phenotype. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:22–5. doi: 10.1177/0883073807307077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappella M. The Rett girls with preserved speech. Brain Dev. 1992;14:98–101. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(12)80094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Average numbers are given in Figure 2. Each of listed pairs is significantly different with p < 0.05 as per Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test.

Average numbers are given in Figure 4. Each of listed pairs is significantly different with p < 0.05 as per Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test.