Abstract

Clinicians who conduct cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) targeting attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adulthood have noted that their patients sometimes verbalize overly positive automatic thoughts and set overly optimistic goals. These cognitions are frequently related to failure to engage in compensatory behavioral strategies emphasized in CBT. In this paper, we offer a functional analysis of this problematic pattern, positively-valenced cognitive avoidance, and suggest methods for addressing it within CBT for adult ADHD. We propose that maladaptive positive cognitions function to relieve aversive emotions in the short-term and are therefore negatively reinforced but that, in the long-term, they are associated with decreased likelihood of active coping and increased patterns of behavioral avoidance. Drawing on techniques from Behavioral Activation (BA), we offer a case example to illustrate these concepts and describe step-by-step methods for clinicians to help patients recognize avoidant patterns and engage in more active coping.

Keywords: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, ADHD, cognitive-behavioral therapy, avoidance, automatic thoughts, functional analysis

Cognitive-behavioral therapies for adult ADHD are developing at an encouraging rate with the approaches developed by Safren et al. (2010) and Solanto et al. (2010) meeting criteria as Probably Efficacious Treatments under the guidelines of APA Division 12 (Knouse & Safren, 2013). In addition to emphasizing behavioral compensatory skills to cope with ADHD-related deficits, these approaches and others (e.g., Ramsay & Rostain, 2008) incorporate cognitive restructuring to target maladaptive cognitions associated with anxiety and depression. After a lifetime of perceived failure and negative feedback from others, it stands to reason that adults with ADHD are likely to develop patterns of negative, self-defeating thoughts that undermine their behavior change efforts (Safren, Perlman, Sprich, & Otto, 2005). Such cognitions are elevated in adult ADHD samples (Mitchell, Benson, Knouse, Kimbrel, & Anastopoulos, 2013) and may put them at-risk for depression (Knouse, Zvorsky, & Safren, 2013). Yet, clinically, we have observed that our adult patients with ADHD report another flavor of cognition that can be just as problematic in its relationship with skill use, for example:

“I'm a good person, so things are just going to work out for me.”

Certainly, no clinician would argue that positive thoughts such as this should be eradicated from a patient's repertoire, but some “positive” thoughts may have a significant downside functionally for patients with ADHD. The clinical phenomenon that we address in this paper is that of overly optimistic automatic thoughts that occur “in vivo” in response to events in a patient's life and that are associated with a decreased likelihood of engaging in active coping and skill use. We propose that these thoughts, despite their feel-good content, function to help the patient escape from negative emotions and that they often represent the first step in a pattern of behavioral avoidance. Placing our focus squarely upon the function of these thoughts, we refer to this pattern as positively-valenced cognitive avoidance.

Although we are not aware of any published data that would allow us to estimate the prevalence of this phenomenon in adults with ADHD, in our clinical experience the issue of overly positive thoughts associated with avoidant behavior has arisen at least once in the vast majority of adult ADHD cases that we have treated and, for a substantial minority of patients, cognitive avoidance has been a recurrent, habitual issue that is a key stumbling block to the use of compensatory CBT skills. In searching the clinically-oriented literature on this topic, we were only able to locate a few papers that specifically discuss the role of problematic positive thoughts in adult ADHD, including a case that involved following a traditional cognitive therapy approach (Mitchell, Nelson-Gray, & Anastopoulos, 2008). In other clinically-oriented writings, Sprich, Knouse, Cooper-Vince, Burbridge, and Safren (2010) and Knouse and Safren (2011; 2013) have discussed their observations regarding overly positive cognitions in adults with ADHD and advised clinicians to be watchful for this phenomenon and to address it using cognitive restructuring techniques. Related clinical observations have included overly optimistic time estimation (Zylowska, 2012) and unrealistic expectations related to overestimating ability (e.g., Ramsay & Rostain, 2008). Empirical work on overly positive cognitions in adults with ADHD is even more limited with the few existing studies discussed below.

Thus, despite awareness of this phenomenon among clinicians who routinely work with adults with ADHD, it has received little empirical study and has not been the specific focus of clinically-oriented discussion in the literature. Therefore, our aim is to offer a description and definition of the phenomenon, summarize the existing although limited research on it, and suggest a method for addressing these cognitions and their consequences based upon functional analysis. By functional analysis, we refer to the evaluation of antecedents and consequences functionally related to a behavior that may play a role in its origin or maintenance (Kazdin, 2001). Here we use the term “behavior” to encapsulate cognition as a private form of behavior similar to other applications of behavior therapy (e.g., Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). We hope that our efforts here spur more interest in and empirical study of the role of positively-valenced cognitive avoidance in adult ADHD and its clinical management.

Overly Positive Thoughts in ADHD: What Do We Know?

ADHD and Positive Illusory Bias

Children with ADHD are more likely than typically developing children to display the positive illusory bias (PIB) where their self-reported competence ratings are substantially higher than their actual competence (Hoza, Pelham Jr, Dobbs, Owens, & Pillow, 2002; Owens, Goldfine, Evangelista, Hoza, & Kaiser, 2007). Although typically developing children also over-estimate their competence, particularly at younger ages, PIB in children with ADHD is often observed despite poorer-than-average performance in over-estimated domains (Hoza et al., 2004). PIB in children with ADHD is more strongly associated with hyperactive-impulsive symptoms than inattentive symptoms (Owens & Hoza, 2003) and increases in PIB across development are associated with increasing aggression (Hoza, Murray-Close, Arnold, Hinshaw, & Hechtman, 2010). Importantly, children with more pronounced PIB have been observed to respond more poorly to behavioral treatment for ADHD (Mikami, Calhoun, & Abikoff, 2010).

Thus, a pattern of overly positive judgments of competence has been documented for some children with ADHD in the very domains in which they experience difficulties. However, recent research calls into question both the pervasiveness of these biases in ADHD and their meaning when they are measured using discrepancy scores (Swanson, Owens, & Hinshaw, 2012). Important for the current discussion, the extent to which any childhood positive illusory biases persist into adulthood is unclear. Evidence of PIB in the global judgments of adults diagnosed with ADHD has been limited to perceptions of driving ability (Knouse, Bagwell, Barkley, & Murphy, 2005; Prevatt et al., 2012). In other major domains, as children with ADHD grow up and experience repeated failures and negative feedback, they may “get the message” and be less likely to espouse over-inflated global self-perceptions. As the environment becomes less structured and supportive while functional impairment increases, adults with ADHD may become painfully aware of their problems. Longitudinal studies from Barkley, Murphy, and Fischer (2008), who followed 158 hyperactive children, support the idea that self-awareness of ADHD-related problems increases across young adulthood. At age 21, participants tended to under-report ADHD symptoms and impairment compared to parent report—however, by age 27, self-reported symptoms and problems increased, converging with parental report.

The high rate of depressive disorders in adults with ADHD (Kessler et al., 2006) provides additional evidence that the overly positive automatic thoughts we have observed in our patients may not reflect PIB in broad domains. Rather than over-inflated self-perceptions, depression is associated with overly negative views of self, world, and future (Beck, 1995). PIB appears to be incompatible with depression, as a longitudinal investigation by Hoza et al. (2010) found a reduction in PIB in children with ADHD was associated with increasing depressive symptoms. In boys with ADHD, reductions in self-ratings of competence similarly predicted increases in depressive symptoms (McQuade, Hoza, Waschbush, Murray-Close, & Owens, 2011). For people with ADHD, self-awareness may be a double-edged sword. As self-perceptions become less inflated and better calibrated due to environmental feedback, this may increase the risk for developing overly negative attitudes, further increasing risk for depression. In recent studies of adults with ADHD, negative automatic thoughts and dysfunctional attitudes are elevated (Mitchell, Benson, et al., 2013) and partially explain the relationship between ADHD symptoms and depression (Knouse et al., 2013).

Thus, while ADHD in childhood may be associated with overly-inflated self-perceptions of competence in broad domains, by adulthood patients are more likely to struggle with overly negative views of their own competence. We suggest that the overly positive cognitions that arise in clinical work with adults with ADHD may not reflect la belle indifference of the positive illusory bias but instead reflect in-the-moment responses to negative emotions that function to reduce or avoid those unpleasant emotions. As such, instead of focusing directly on calibrating patients' thoughts to reality, we recommend that clinicians instead help patients change the behavioral outcomes associated with these thoughts.

Overly Positive “Automatic” Thoughts

Along with clinical observations, preliminary empirical research explores the presence and consequences of overly optimistic automatic thoughts in adult ADHD. Noting the presence of such problematic thoughts in our own patients, with our colleagues we created a self-report measure modeled on the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (Hollon & Kendall, 1980) tapping cognitions that might occur more frequently in adults with ADHD—many of which could be described as “overly optimistic” (e.g., “I do better waiting until the last minute.”). Scores on a 20-item version of the measure in a clinical sample of adults diagnosed with ADHD (n = 95) were correlated with investigator-rated and self-reported ADHD symptom dimensions (r = .43 - .60) and with functional impairment in social relationships, money management, driving and with GAF score (Anastopoulos et al., 2013). Although many of these cognitions can be described as “positive” or “optimistic” in terms of their content, they were nonetheless associated with poorer functioning, suggesting that their psychological and functional impact may be negative1.

As described in detail below, our functional analytic approach reconciles the seemingly conflicting observations that adults with ADHD exhibit elevated rates of negative automatic thoughts and are at-risk for depressive disorders yet simultaneously endorse elevated rates of overly optimistic thoughts associated with functional impairment. We propose that the excessively “positive” thoughts observed in adults with ADHD become problematic when they reduce aversive emotions in the short-term but increase avoidant behavior and reduce compensatory skill use in the long-term. Thus, these superficially “positive” thoughts precipitate avoidant behavior in a manner similar to negative automatic thoughts, which contributes to risk for depression (Knouse et al., 2013). Although the topography of the thought may be positive, its impact is decidedly negative.

Other research findings may provide evidence of the nature of automatic thoughts in adult ADHD. Research on responsiveness to immediate rewards in ADHD provides some indirect evidence of a relationship between the disorder and in-the-moment overly positive expectations. For instance, in a study comparing performance on a behavioral task of responsiveness to immediate rewards and a self-report measure of sensitivity to reward, adults with ADHD scored significantly higher than their non-ADHD peers on both indices of reward responsiveness (Mitchell, Robertson, Kimbrel, & Nelson-Gray, 2011). These findings are consistent with studies assessing the relationship between sensitivity to reward and ADHD symptoms in children and adults (Becker et al., 2013; Luman, van Meel, Oosterlaan, & Geurts, 2012;Mitchell, 2010). Such responsiveness to reward is moderated by reward expectancy (Corr, 2002). Consistent with our focus on cognitions, this reward expectancy may emerge as overly optimistic cognitions. In addition, despite ADHD being linked with social maladjustment, young adults diagnosed with ADHD do not evidence any differences in rejection sensitivity, a tendency to expect or perceive rejection, than their non-ADHD peers (Canu & Carlson, 2007).

Additional empirical work is needed to more fully describe the frequency, prevalence, and correlates of overly positive automatic thoughts in adult ADHD. For example, there are currently no data that could be used to estimate the proportion of adult patients with ADHD who exhibit problematic levels of overly optimistic automatic thoughts, which would clearly be useful information for clinicians. While additional information on the relationship between these thinking patterns and global measures of functional impairment will be important, more fine-grained methodological approaches may be needed to better understand the immediate antecedents and consequences of overly positive automatic thoughts, such as ecological momentary assessment. While clinicians await additional empirical investigations of overly positive thoughts in ADHD, they must continue to rely upon careful assessment and functional analysis in each individual client when choosing to address potentially maladaptive cognitions.

CBT Approach to Overly Positive Thoughts in Bipolar Disorder

Overly positive thoughts have also been the subject of clinical attention in bipolar disorder. We briefly compare this literature with current cognitive-behavioral approaches for adult ADHD and with our suggested approach. Hypomania is associated with unrealistically high goals and increasing overconfidence in one's abilities. People at-risk for the disorder may become more overconfident in the face of success than their peers, which suggests that an overly positive cognitive style may be a risk factor for hypomania—although no prospective studies have examined this hypothesis (Johnson & Tran, 2007). Escalating overconfidence may signal the onset of a hypomanic episode and set the occasion for impulsive behavior, which is a good reason for clinicians who treat bipolar disorder to attend to these types of thoughts.

A few current CBT approaches for bipolar disorder address overly positive thoughts associated with hypomania by adapting cognitive restructuring with the goal of preventing the escalation of a hypomanic episode and the potentially destructive behaviors occasioned by overly optimistic thinking. Notably, the approaches of both Otto et al. (2009) and Lam and colleagues (2010) more heavily emphasize teaching the client to evaluate the adaptiveness of thoughts rather than their validity. (For example, see Otto et al., 2009 p. 22 where it is recommended that optimistic thoughts be evaluated as “Useful or not.”) Although this recommendation is based on a different line of reasoning than the one we describe in this paper, it is nonetheless notable that greater focus on adaptiveness of thoughts emerges independently in the bipolar CBT literature on overly positive thoughts. As discussed below, our approach emphasizes the adaptiveness of overly positive thoughts from a functional analytic perspective, where the primary goal is to change the behavioral outcome associated with the thought rather than its content.

Positively-Valenced Cognitive Avoidance: A Functional Analysis

In this section, we present a functional analysis of overly positive cognitions and make the case that many instances of these thoughts may be conceptualized as positively-valenced cognitive avoidance. We begin by describing how maladaptive cognitions are addressed in current CBT for adult ADHD.

Cognitive Restructuring in Current CBT for Adult ADHD

In addition to teaching specific compensatory skills, manualized treatments for adult ADHD that have undergone randomized controlled trials include cognitive therapy modules that primarily target anxiolytic and depressogenic cognitions (Safren et al., 2005; Solanto, 2011). These cognitions are thought to undermine self-management and are targeted following traditional cognitive restructuring techniques (Beck, 1995) that were later adapted for adults diagnosed with ADHD (McDermott, 2000). Consistent with traditional cognitive therapy, changing the content of thoughts, which are labeled as negative, distorted, irrational, or erroneous, is emphasized. Patients are taught to identify distorted cognitions and maladaptive beliefs, which are then tested empirically via cognitive restructuring exercises that involve labeling thinking errors and creating rational responses. The goal of such exercises is to change the distorted content of the cognitions.

Overly positive cognitions can also be targeted using this model (Sprich et al., 2010). For instance, Table 1 is an example of a Daily Thought Record addressing this type of thought. Here, the automatic thought that, “I'm a hard worker when it comes down to the wire, so I'll do it later,” is maladaptive given that it leads to procrastination in a way similar to a negative automatic thought. Restructuring these cognitions while emphasizing their problematic consequences is consistent with current models from existing treatment manuals. A patient may restructure such thoughts with responses such as, “Hard workers get started early and break tasks into smaller, concrete steps,” and, “I'm a hard worker and waiting until the last minute lessens the quality of my work.”

Table 1. Sample of a Daily Thought Record and cognitive therapy approach to responding to overly optimistic cognitions.

| Time and Situation | Automatic Thoughts | Mood | Thinking Error | Rational Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At library, Monday. Classmate reminds me of big paper due in 2 weeks | I'm a hard worker when it comes down to the wire, so I'll do it later | Relief – 8/10 Happy – 5/10 | Jumping to conclusions | Breaking tasks into their smaller components makes it less stressful |

Notes. For this example, patients may also argue in the rational response column that they are hard workers and that they will be able to complete the task at the last minute.

What is unique about overly positive cognitions is that the emotions that follow are positively-valenced and they are likely associated with escape from aversive emotions. Although the ultimate purpose of traditional cognitive therapy is to increase skillful behavior, changing thought content is central to this process. Since the to-be-changed cognitions are positively-valenced, it may be difficult to convince patients that their “positive thinking” should be labeled “irrational” or “erroneous.” Although following a traditional cognitive framework is not necessarily contraindicated, therapists may find themselves arguing against positively-valenced cognitions that patients may be particularly reluctant to challenge. For example, some patients may consider their perceived ability to complete a lot of work at the last minute to be a strength and thus have little willingness to challenge that thought. Further, the thought may be accurate—the adult with ADHD may, in fact, be a hard worker when he or she is up against a deadline. Thus, targeting these cognitions based on their accuracy and content may contribute to therapists being perceived as trying to convince patients that “positive thinking is wrong,” which could negatively impact rapport and the therapeutic progress, and unnecessarily shift the focus of therapy away from how a patient relates to his or her own thoughts. An alternative approach is to engage the patient in a functional analysis of these thoughts.

Functional Analysis of Overly Positive Thoughts

Why Functional Analysis?

One emphasis of this review is on the function of thoughts, as opposed to their structure or content. This distinction follows from traditional behavioral approaches to assessment and treatment (Farmer & Nelson-Gray, 2005). Whereas structure or content of cognitions focuses on descriptive features independent of the context of that cognition, a functional approach explicitly incorporates an analysis of the antecedent conditions that may set the stage for a cognition to occur and the consequences that follow. Current CBT treatment manuals for adults with ADHD include cognitive restructuring exercises that emphasize aspects of both function (i.e., the antecedent column and consequence columns in Table 1) and structure (i.e., the type of cognition column in Table 1). What we emphasize here is working with patients to identify how their thoughts and behaviors function (e.g., to escape from an activity perceived as “boring”), while avoiding a potential pitfall in labeling cognitions as “irrational” or “distorted” with patients who may see these overly optimistic cognitions as accurate, factual, an indication of themselves as positive people, and so on. The emphasis on the function of these cognitions sidesteps this potential hurdle altogether and also circumvents the definitional problem of what constitutes “too much” optimism or pessimism. The focus is on the outcomes associated with thoughts rather than their accuracy.

Avoidance Function of Overly Positive Thoughts

From a functional analytic perspective, our hypothesis is that a key feature of many problematic “positive” cognitions is that they are negatively reinforced because they are associated with the removal of aversive emotions. In other words, they represent positively-valenced cognitive avoidance. For example, in Table 1, the patient notes “relief” as one of the emotional responses to having the thought about being able to get work done at the last minute. If we were to ask the patient what emotions he or she experienced relief from—i.e., what they initially felt when their friend reminded them about the looming assignment—they might report that they initially felt anxious, trapped, annoyed, or burdened. The “rose-colored” thought, then, is associated with immediate escape from these aversive emotions. Over time, as the act of thinking these overly optimistic thoughts is negatively reinforced, patients may come to respond more and more readily in similar discomfort-producing situations with positively-valenced cognitive avoidance. Certain thoughts may be particularly effective at relieving aversive emotional states and these may become a staple in the patient's cognitive-behavioral repertoire to the point of automaticity. (Clinically, we refer to these frequent thoughts as “red flag thoughts.”) We argue that the mechanism of negative reinforcement explains why these thoughts are so seductive and problematic—not only do they “sound good” to the patient but they also “feel good” in the sense that they are associated with both reductions in discomfort and increases in positive emotion.

Consistent with delay aversion accounts of ADHD involving abnormalities in dopaminergic-based neurological pathways subserving motivational processes (Sonuga-Barke, 2003), patients with ADHD may have greater difficulty tolerating unpleasant emotions that emerge when they are considering a task that needs to be completed and prefer the immediate negative reinforcement received when engaging in avoidance. Active coping would require a greater delay in reinforcement. A study using in-the-moment assessments of thoughts and emotions in daily life found that participants with higher inattentive ADHD symptoms were more likely to dislike their current activity and to endorse a stronger preference to be doing something else (Knouse et al., 2008). If adults with ADHD experience more negative affect when encountering tasks in daily life, they may be more vulnerable to avoidance-motivated coping.

In this paper, we suggest teaching patients to conduct a functional analysis of these thoughts in order to increase awareness of their consequences and set the occasion for alternatives to avoidance. This approach to cognitions is consistent with third wave behavioral interventions that focus on changing the function of psychological events and the patient's relationship to them rather than changing the events themselves (e.g., Hayes et al., 2006).

Examples of Functional Analysis

To further illustrate functional analysis, we integrate a teaching tool used in Behavioral Activation (BA) (Martell, Addis, & Jacobson, 2001; Martell, Dimidjian, & Herman-Dunn, 2010). BA is a functional analytic approach developed for the treatment of depression (Jacobson, Martell, & Dimidjian, 2001). The treatment focuses on helping patients increase access to positive reinforcement and emphasizes changing avoidance-motivated behaviors that block access to reinforcement and maintain depression (Ferster, 1973). Patterns of avoidance are associated with short-term relief from discomfort, but in the long-term, they contribute to secondary problems that perpetuate the cycle of depression (Jacobson et al., 2001). A key process in avoidance modification in BA is teaching patients to conduct functional analyses of their lives so that they can recognize when automatic avoidance-motivated behavior is carrying them further away from their long-term goals. This focus on teaching patients to recognize and counter avoidance makes BA strategies particularly applicable to positively-valenced cognitive avoidance. Specifically, we will illustrate how clinicians can apply the “TRAP/TRAC” psychoeducational tool from BA (Martell et al., 2001) to the functional analysis of overly positive thoughts.

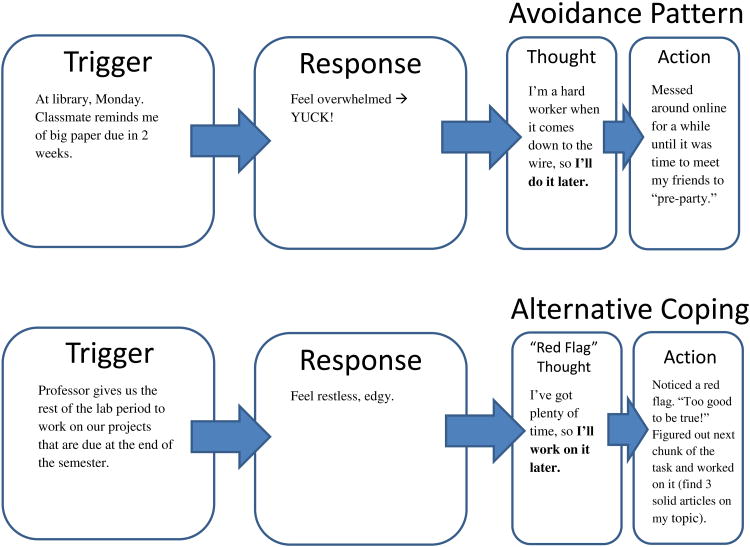

The TRAP/TRAC model provides a framework to help patients recognize the downsides of cognitive avoidance, to understand the motivation for these thoughts, and to help them recognize such thoughts as opportunities for active coping. Figure 1 illustrates our adaptation of the model as presented in Martell et al. (2010) and an example of its use with the hypothetical patient whose self-monitoring appears in the Daily Thought Record in Table 1. “T”in TRAP stands for Trigger and is analogous to the activating event or situation from the Daily Thought Record. “R” stands for Response and refers to the patient's immediate emotional response elicited by the Trigger. “AP” stands for Avoidance Pattern. The Avoidance Pattern includes the (possibly) over-optimistic cognition that the patient reports and any accompanying observable behaviors. The clinician should probe for any such actions that were associated with the thought that serve to avoid “dealing with” the triggering event in an adaptive way—particularly if there was a missed opportunity for use of skills learned during prior sessions of CBT.

Figure 1.

Example TRAP/TRAC Model for Positively-Valenced Cognitive Avoidance. Adapted from Martell et al. (2010, p. 197).

In the example illustrated in Figure 1, the Avoidance Pattern involved a positively-valenced cognition (i.e., “I'm a hard worker when it comes down to the wire, so I'll do it later.”), which provided immediate relief from the Response of feeling overwhelmed, but also precipitated behavior inconsistent with skill use and dealing effectively with the problem (e.g., spending time on an alternative activity and then leaving the library). The bottom half of Figure 1 illustrates TRAC, an alternative pathway. A patient who can recognize his or her typical pattern of cognitive avoidance, or “red flag” thoughts, might instead engage in Alternative Coping (“AC”). Recognizing a trigger-response-red flag pattern that is familiar (Opportunity to work on big project → negative emotion → “I'm a hard worker when it comes down to the wire, so I'll do it later.”), this patient might instead choose an active coping skill learned in CBT—such as breaking down the task into less overwhelming pieces.

Another example from one of our colleagues' CBT work illustrates the model. A patient who lived in the suburbs was chronically late to her appointments in the city—a problem that seemed to be preceded by the thought, “I only really need 20 minutes to get there”, which co-occurred with delaying her departure repeatedly until it was highly unlikely she would be able to arrive on time. The patient would recall a single, atypical instance in the past when she had been able to drive into the city and arrive on-time to her appointment in only 20 minutes. When the clinician and patient discussed the problem, they discovered that when it would occurred to the patient that she might need to stop what she was doing and leave for an appointment (Trigger) she was often absorbed in an engaging activity and did not want to “switch gears” and fight traffic (Response). This was followed by the “positive” thought and persistence in the preferred activity (Avoidance Pattern). The clinician and patient then worked together to use the overly optimistic thought as a cue to carry out a specific behavioral plan for getting out of the house on time (Alternative Coping).

In the next section, we use a case example from one of our own clients to illustrate steps that clinicians can take to work with patients exhibiting problematic positively valenced cognitive avoidance and spur them toward more active coping.

Case Example: Working with Positively-Valenced Cognitive Avoidance

The case example we present illustrates the following steps, which we recommend to clinicians when they suspect that cognitive avoidance may be in play.

Conduct an interactive functional analysis and psychoeducation about cognitive avoidance

Formulate strategies to increase awareness of cognitive avoidance in “real time”

Coach alternative coping and skill engagement

While the strategies we suggest could certainly be used in a modular way as in a manualized treatment, clinicians may find opportunities to use these tools “on the fly” when they detect possible cognitive avoidance while teaching and troubleshooting other skills, as our case example illustrates. In either situation, the same basic steps may be helpful.

Case Example: Background

A female patient in her mid-40's who we will call “Rose” presented for therapy primarily involving concerns about her relationship with her husband and children. These relationships had been negatively impacted by the patient's difficulty managing daily tasks and disorganization at home. Such difficulties had resulted in daily stressors that impacted the family, such as cluttered rooms full of items that were of no emotional attachment to the patient that rendered them unusable (including a bedroom that one of her children was unable to move into for over a year and a general living area that prohibited family members from inviting over guests). After an assessment to rule out any hoarding behavioral tendencies and to establish that disorganization, a core symptom of ADHD, was an appropriate target for treatment and that she met diagnostic criteria for ADHD, we began administering CBT following Safren et al.'s (2005) manual. In addition to introducing techniques to help the Rose learn ways to organize (i.e., behavioral strategies) and ways to overcome depressogenic cognitions that interfered with organizing (i.e., cognitive strategies), we observed problematic optimistic cognitions emerge in the patient's Daily Thought Records. Examples of these cognitions included “It will only take 30 minutes to take care of this—I'll do it later,” “I do my best work ‘under the gun,’” and, “I know I'll be able to get it done, but now isn't the right time.”

After attempting more traditional cognitive therapy techniques using cognitive restructuring and Daily Thought Records, ongoing assessment indicated that we were not making much progress. In addition, the therapist-patient relationship began to seem less collegial, which was later supported by Rose stating in session that she felt like some of these cognitions had helped her through a lot in life and that the therapist was not being respectful of that by advocating that they be challenged. We therefore decided to modify our approach to these thoughts.

Case Example: Interactive Functional Analysis and Psychoeducation

We engaged in a functional analysis in which we examined the typical behavioral pattern that led to avoidance of spending time using organizational strategies introduced earlier in therapy. This was typically conducted when Rose identified goals she did not complete from the previous week. The TRAP/TRAC model was proposed as an alternative approach that might help reach her therapy goals. Given that goals for therapy were firmly established at this point and the patient had some success using traditional cognitive therapy for depressive cognitions but not other cognitions, the patient agreed with the rationale to attempt a new approach. The TRAP/TRAC model was briefly introduced by the therapist, which was then followed by a demonstration of the model using an example from the patients experience in the past week. Rose was able to establish a chain of events that fit the TRAP model: a Trigger (i.e., the patient would see the room in her house, then experience a thought that the room needs to be organized), then a negative emotional Response (i.e., feeling overwhelmed), then an Avoidance Pattern that included an overly optimistic cognition (e.g., “it will only take 30 minutes and I've got time to do it later”), behavioral avoidance, and a reduction in feeling overwhelmed. The focus on avoidance that ultimately led to the patient not meeting her goals in therapy refocused both therapist and patient toward the impact of her behavioral repertoire while circumventing concerns noted above regarding the therapist-patient relationship. Over the next week, Rose was asked to use the TRAP portion of the model to observe what typically occurred.

Comment

When a clinician suspects positively-valenced cognitive avoidance, the first step is to collaboratively conduct a functional analysis of the situation with the patient. An interactive functional analysis has two purposes: assessment and psychoeducation. As most skilled CBT therapists recognize, psychoeducation proceeds best when it is an interactive dialogue between therapist and patient using situations drawn directly from the patient's own life. Here, we recommend using the TRAP/TRAC model as illustrated above in helping patients to recognize how positively-valenced thoughts that link to avoidant behavior provide relief from uncomfortable feelings in the short-term, but may compound problems in the long-term. This allows the clinician to focus on the function of the thought rather than its content. Therapist and patient should also assess whether there are any recurring patterns to the optimistic thoughts. Are they more likely to occur in certain situations? In response to similar emotions? Is there one particular thought that occurs over and over—a “red flag” thought? Such “red flag” thoughts are probably those that have been particularly effective at reducing aversive emotions in the past and have thus been negatively reinforced many times. The clinician can draw attention to any recurring patterns and explain that learning to notice these habitual thoughts occurring in “real time” will give the patient an opportunity to engage in more effective, active coping strategies.

Case Example: Increasing Awareness of “Real Time” Avoidance

During the week that she used the TRAP model to observe her thoughts, Rose noticed some recurrent “red flag” thoughts on the theme that it would be better to do a particular task later when she would have “more time.” In subsequent sessions, Rose learned how to better recognize possibly avoidant thoughts in vivo through an application of mindfulness (i.e., practicing noticing thoughts as impermanent mental events without judgment or being self-critical) and use of a vivid metaphor in which overly positive thoughts were conceptualized as mental rose-colored glasses. Mindfulness meditation techniques adapted for adult ADHD were introduced (Zylowska, 2012) to create a context in which the patient could notice her cognitive responses without engaging these cognitions as “right or wrong” but instead focusing on whether the thoughts were pulling her to behave in ways that would move her either closer to or further away from important goals.

Comment

The next key to engaging in alternative coping is to help the patient become aware, in “real time,” of when an avoidance pattern is occurring so that he or she has a chance to choose an alternative behavior. The therapist should emphasize that habitual “red flag” thoughts, situations, or emotions can be used as cues that avoidant behavior is likely to occur and active coping skills need to be engaged. First, however, the patient needs to be able to “see” a red flag thought when it occurs and “catch it in flight” if they are to have the chance to use it as a behavioral inflection point. Possible methods of increasing awareness include assigning patients to self-monitor or “just notice”urges to avoid and red flag thoughts during the coming week. A Daily Thought Record could also be used but may not be required, particularly if the patient is trying to observe instances of one particular recurrent thought.

In trying to increase a patient's real-time awareness of cognitive avoidance patterns, clinicians can creatively apply a variety of CBT tools. Once particularly vulnerable situations or recurrent thoughts are identified, the patient might use visible reminders in the everyday environment to further heighten awareness. For example, one of our patients wrote his red flag thoughts on fluorescent Post-It notes and put them in his office workspace. This helped him to better recognize when the thoughts were occurring in-the-moment and use them as a cue that avoidant behavior was imminent. As in Rose's case, application of mindfulness techniques may also aid in helping patients notice these cognitions (Mitchell, Zylowska, & Kollins, 2013). Another tool illustrated in the case study is the use of vivid and meaningful visual metaphors that easily come to mind at key moments (Hayes et al., 2012). The use of self-instructional phrases or “mantras” as discussed in Solanto's (2011) treatment manual for adult ADHD may be memorable as well (e.g., “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.”). Finally, role-playing and covert rehearsal of typical avoidance patterns and alternative coping may better prepare a patient to recognize cues and then enact a more adaptive pattern.

Case Example: Coaching Alternative Coping and Skills Engagement

Rose's ability to recognize possible “red flag” thoughts improved considerably, which gave her more opportunities to choose active coping instead of avoidance. Thus, instead of changing thoughts, Rose was asked to focus on changing her behavior. For Rose, the Alternative Coping (“AC”) component of the TRAC model involved implementing behavioral strategies introduced earlier in therapy, including starting on an easier portion of the task or setting a time limit so that working on organizational tasks did not feel so overwhelming.

Comment

As patients begin to notice instances of their red flag thoughts and habitual avoidance patterns, they can increase their frequency of engaging with any of the organization, planning, time-management, or self-motivation skills that are part of CBT for adult ADHD as appropriate. The therapist can emphasize that noticing an old, avoidant pattern beginning to occur is a chance to ask one's self what skill or strategy could be useful in that particular instance. Put another way, noticing a red flag thought can serve as the situational cue for an implementation intention. Implementation intentions are statements of goal-directed actions a person will take in a specific situation and can be expressed as, “If situation X occurs, then I will perform action Y in line with my goals.” (Gollwitzer & Oettingen, 2011). Formulating goals in this way increases the likelihood of achievement over and above the effects of simple goal-setting (i.e., “I will reach Goal X.”) (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006). For example, the patient illustrated in Figure 1 could state the implementation intention, “When I notice the thought ‘I'll just do it later,’ I will instead work on the task for ten minutes” (see Ramsay, 2002 for a discussion of the “10 Minute Rule”). Thus, noticing an urge to avoid becomes a cue to engage.

Importantly, the therapist should take a non-judgmental stance when the patient has difficulty at first engaging in an alternative coping, emphasizing that the old avoidance pattern has been continually reinforced over time and that it stands to reason that, initially, the TRAPs will outnumber the TRACs. It is an increase in the frequency of active coping over time—not an absolute eradication of avoidant behavior—that signals progress.

Applying the Model to Overly Optimistic Goals

To augment our case example, we thought it would be useful to discuss another situation in which clinicians may frequently encounter the nefarious effects of positively valenced cognitive avoidance—goal-setting. The organization and planning techniques that are central to CBT for adult ADHD involve creating prioritized daily task lists and setting concrete, specific, and reasonable goals. Anecdotally, patients often set behavioral goals that are unrealistic given their past performance (Ramsay & Rostain, 2008). For example, a college student may set a goal to study for three hours in a single sitting or a sedentary patient may state an intention to go to the gym every day in the upcoming week. Most CBT therapists would immediately recognize the need to make these goals more modest to increase the likelihood that the client will attain them, thereby increasing the likelihood of incremental success and motivating further work toward behavior change. A daunting initial first step is more likely to be avoided. Furthermore, overly ambitious, perfectionistic goals may set the occasion for the “what the hell” effect whereby failure to attain the lofty goal results in the patient giving up on the target behavior altogether (Soman & Cheema, 2004).

Are overly ambitious goals a form of positively-valenced cognitive avoidance and does our clinical approach have anything to add? Applying the TRAP/TRAC model to the example of the sedentary patient who sets a goal of exercising every day provides an illustration. Discussing past difficulties with health-related behaviors like exercise and healthy eating may provoke uncomfortable feelings. The Trigger, then, might be the discussion and the therapist's suggestion that the patient set an exercise goal for the next week. Even if the patient wishes to pursue an exercise goal, his or her Response may include feeling anxious or ashamed when recalling past unsuccessful attempts. Setting an unrealistic lofty goal to “exercise every day” would then be part of the Avoidance Pattern in that it functions to relieve these aversive emotions in the moment but does not provide a realistic way forward it terms of changing behavior.

But what accounts for the overly optimistic—and, ultimately, maladaptive—form of the initial goal? Why do patients set such ambitious initial goals? Setting the imaginary bar very high may have a stronger anxiety-reducing effect and may also be associated with positive emotions because, in the past, clients may have received social reinforcement when verbalizing ambitious goals. Evidence from the social psychology literature suggests that announcing identity-related goals in a social setting increases the subjective sense that one is closer to attaining the desired identity (Gollwitzer, Sheeran, Michalski, & Seifert, 2009). Over time, ambitious goal-setting is repeatedly reinforced and may appear frequently in the patient's behavioral repertoire, even it if never results in actual achievement.

Clinically, if a functional analysis suggests that overly ambitious goal-setting is part of an avoidance pattern, therapist and patient can conceptualize it using the TRAP model, devise ways to increase awareness of this tendency in daily life, and decide which Active Coping patterns to use—in this case, setting specific, modest goals or breaking off a manageable piece of an overwhelming task. For the case study example discussed above, overly ambitious goal-setting as positively-valenced cognitive avoidance emerged when discussing items on the patient's prioritized task list. The patient set goal to spend 30 minutes organizing in a certain room of the house each day, although the patient's baseline for this behavior was zero minutes per day. We identified that this established a pattern of avoidance in which the patient experienced relief from the overwhelming feelings provoked by thinking about organizing the house when she set a lofty goal. We discussed how more modest goals may result in less procrastination and avoidance and, most importantly, supported the patient in choosing and succeeding at those more reasonable goals.

Conclusions

Although additional research is warranted to assess characteristics of overly positive cognitions in adults with ADHD, clinically-oriented articles identify these types of cognitions as important in the treatment of this population. In this manuscript we propose conceptualizing such maladaptive cognitions as positively-valenced cognitive avoidance and suggest a guiding framework for clinicians to assess and target this process in adults diagnosed with ADHD. We propose a functional analytic framework that focuses on the escape and avoidance functions of these cognitions to supplement more traditional cognitive therapy techniques in CBT approaches to ADHD in adulthood. We argue that the approach summarized here can be used to tailor treatment to the unique needs of adult ADHD patients. We hope that this discussion spurs additional research on overly positive cognitions in adult ADHD and we emphasize the need for additional empirical study of these strategies and of other individual components of CBT for adult ADHD.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Knouse was supported while writing this manuscript by a Faculty Summer Research Fellowship from the University of Richmond. Dr. Mitchell was supported by award number K23 DA032577 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Susan Sprich for permitting us to include a description of one of her clinical cases as an example in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Thus, the “positive” cognitions that we focus on in this article can be differentiated from more adaptive positive cognitive patterns measured by scales like the Positive Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (Ingram & Wisnicki, 1988).

References

- Anastopoulos AD, Benson JW, Mitchell JT, Knouse LE, Kimbrel NA, Bray AC. Development of a measure for assessing AD/HD-related automatic thoughts. Poster session presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Assocation; Honolulu, HI. 2013. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD in adults: What the science says. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS. Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Fite PJ, Garner AA, Greening L, Stoppelbein L, Luebbe AM. Reward and punishment sensitivity are differently associated with ADHD and sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms in children. Journal of Research in Personality. 2013;47:719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corr PJ. J.A. Gray's reinforcement sensitivity theory and frustrative nonreward: A theoretical note on expectancies in reactions to rewarding stimuli. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00115-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer RF, Nelson-Gray RO. Personality-guided behavior therapy. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ferster CB. A functional analysis of depression. American Psychologist. 1973;28(10):857–870. doi: 10.1037/h0035605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM, Oettingen G. Planning promotes goal striving. In: Vohs KD, Baumeister RF, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. Second. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in experimental social psychology. 2006;38:69–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P, Michalski V, Seifert AE. When intentions go public: Does social reality widen the intention-behavior gap? Psychological Science. 2009;20(5):612–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, second edition: The process and practice of mindful change. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Kendall PC. Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1980;4(4):383–395. [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Gerdes AC, Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE, Pelham WE, Jr, Molina BSG, et al. Wigal T. Self-perceptions of competence in children with ADHD and comparison children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):382–391. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.72.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Murray-Close D, Arnold LE, Hinshaw SP, Hechtman L. Time-dependent changes in positively biased self-perceptions of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(02):375–390. doi: 10.1017/S095457941000012X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Pelham WE, Jr, Dobbs J, Owens JS, Pillow DR. Do boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder have positive illusory self-concepts? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(2):268–278. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.111.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Wisnicki KS. Assessment of positive automatic cognition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):898–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Martell CR, Dimidjian S. Behavioral activation treatment for depression: Returning to contextual roots. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8(3):255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Tran T. Bipolar disorder: What can psychotherapists learn from the cognitive research? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63(5):425–432. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Behavior modification in applied settings. 6th. Stamford CT: Wadsworth; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley RA, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. Zaslavsky AM. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–723. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouse LE, Bagwell CL, Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Accuracy of self-evaluation in adults with ADHD: Evidence from a driving study. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2005;8:221–234. doi: 10.1177/1087054705280159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouse LE, Safren SA. Psychosocial treatment of adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. In: Evans SW, Hoza B, editors. Treating Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Knouse LE, Safren SA. Psychosocial treatment for adult ADHD. In: Surman CB, editor. ADHD in adults: A practical guide to evaluation and managment. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Knouse LE, Mitchell JT, Brown LH, Silvia PJ, Kane MJ, Myin-Germeys I, Kwapil TR. The expression of Adult ADHD symptoms in daily life: An application of experience sampling methodology. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2008;11:652–663. doi: 10.1177/1087054707299411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouse LE, Zvorsky I, Safren SA. Depression in adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): The mediating role of cognitive-behavioral factors. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10608-013-9569-5. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam DH, Jones SH, Hayward P. Cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: A therapist's guide to concepts, methods and practice. 2nd. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2010. Cognitive techniques. [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, Acierno R, Daughters SB, Pagoto SL. Ten year revision of the brief Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression: Revised treatment manual. Behavior Modification. 2011;35(2):111–161. doi: 10.1177/0145445510390929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luman M, van Meel CS, Oosterlaan J, Geurts HM. Reward and punishment sensitivity in children with ADHD: validating the Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire for children (SPSRQ-C) Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40(1):145–157. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9547-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR, Addis ME, Jacobson NS. Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. New York: W. W. Norton; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR, Dimidjian S, Herman-Dunn R. Behavioral activation for depression: a clinician's guide. New York: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott SP. Cognitive therapy for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Brown TE, editor. Attention-deficit disorders and comorbidities in children, adolescents, and adults. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. pp. 569–607. [Google Scholar]

- McQuade JD, Hoza B, Waschbush DA, Murray-Close D, Owens JS. Changes in self-perceptions in children with ADHD: a longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and attributional style. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:170–182. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.05.003. doi:0005-7894/10/170–182/$1.00/0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Calhoun CD, Abikoff HB. Positive illusory bias and response to behavioral treatment among children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(3):373–385. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT. Behavioral approach in ADHD: testing a motivational dysfunction hypothesis. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2010;13(6):609–617. doi: 10.1177/1087054709332409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT, Benson J, Knouse LE, Kimbrel NA, Anastopoulos AD. Are negative automatic thoughts associated with ADHD in adulthood? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10608-013-9525-4. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT, Nelson-Gray RO, Anastopoulos AD. Adapting an emerging empirically supported cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults with ADHD and comorbid complications: An example of two case studies. Clinical Case Studies. 2008;7:423–448. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT, Robertson CD, Kimbrel NA, Nelson-Gray RO. An evaluation of behavioral approach in adults with ADHD. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2011;33:430–437. doi: 10.1007/s10862-011-9253-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JT, Zylowska L, Kollins SH. Mindfulness meditation training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adulthood: Current empirical support, treatment overview, and future directions. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Reilly-Harrington N, Kogan JN, Henin A, Knauz RO, Sachs GS. Managing bipolar disorder: A CBT approach therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Goldfine ME, Evangelista N, Hoza B, Kaiser NM. A critical review of self-perceptions and the positive illusory bias in children with ADHD. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10:335–351. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Hoza B. The role of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in the positive illusory bias. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):680–691. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevatt F, Proctor B, Best L, Baker L, Van Walker J, Taylor NW. The positive illusory bias: Does it explain self-evaluations in college students With ADHD? Journal of Attention Disorders. 2012;16(3):235–243. doi: 10.1177/1087054710392538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JR. A cognitive therapy approach for treating chronic procrastination and avoidance: Behavioral activation interventions. Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama & Sociometry. 2002;55:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JR, Rostain A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD: An integrative psychosocial and medical approach. New York, NY US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Perlman CA, Sprich S, Otto MW. Mastering your adult ADHD: a cognitive-behavioral treatment program, therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Sprich S, Mimiaga MJ, Surman C, Knouse LE, Groves M, Otto MW. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. relaxation with educational support for medication-treated adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms. JAMA. 2010;304(8):857–880. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanto MV. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult ADHD : targeting executive dysfunction. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Solanto MV, Marks DJ, Wasserstein J, Mitchell K, Abikoff H, Alvir J, Kofman MD. Efficacy of metacognitive therapy for adult ADHD. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:958–968. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soman D, Cheema A. When goals are counterproductive: The effects of violation of a behavioral goal on subsequent performance. Journal of Consumer Research. 2004;31(1):52–62. doi: 10.1086/383423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS. The dual pathway model of AD/HD: an elaboration of neuro-developmental characteristics. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27(7):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprich S, Knouse LE, Cooper-Vince C, Burbridge J, Safren SA. Description and demonstration of CBT for ADHD in adults. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson EN, Owens EB, Hinshaw SP. Is the positive illusory bias illusory? Examining discrepant self-perceptions of competence in girls with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40(6):987–998. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9615-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylowska L. The mindfulness prescription for adult ADHD: An 8-step program for strengthening attention, managing emotions, and achieveing your goals. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]