Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

To gain a better understanding of the facilitators and barriers to creating a practice-based research network (PBRN) of safety net clinics, we conducted a qualitative study within our network of safety net health centers.

METHODS

Utilizing snowball sampling, we conducted interviews with 19 of our founding stakeholders and analyzed these interviews to draw out common themes.

RESULTS

The results showed four barriers to research in our network: lack of research generated from clinician questions, lack of appropriate funding, lack of clinician time, and lack of infrastructure. We discuss these results and suggest that inadequate funding for practice-based research, particularly in the health care safety net, is a unifying theme of these four barriers.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that the national funding strategy for research relevant to underserved populations and all of primary care must undergo a fundamental shift. We discuss the features of possible models to meet this need.

Recent discussions in the medical literature highlight the disparate priorities of biomedical research and those of primary care practice,1–3 especially primary care among the underserved.4–7 Epidemiologic concerns about population relevance,8,9 as well as the workload burden and the funding limits of safety net providers, yield significant theoretical barriers to research engagement. Over the past several decades, the practice-based research network (PBRN) model has flourished in primary care settings, providing community laboratories for conducting research and answering questions relevant and targeted to primary care.10–13 Ideally, the model centralizes and actively engages primary care providers and staff in the design, performance, and dissemination of research. It is uncertain, however, whether this model successfully bridges the gap between the agendas of the biomedical research community and those of providers for the underserved.

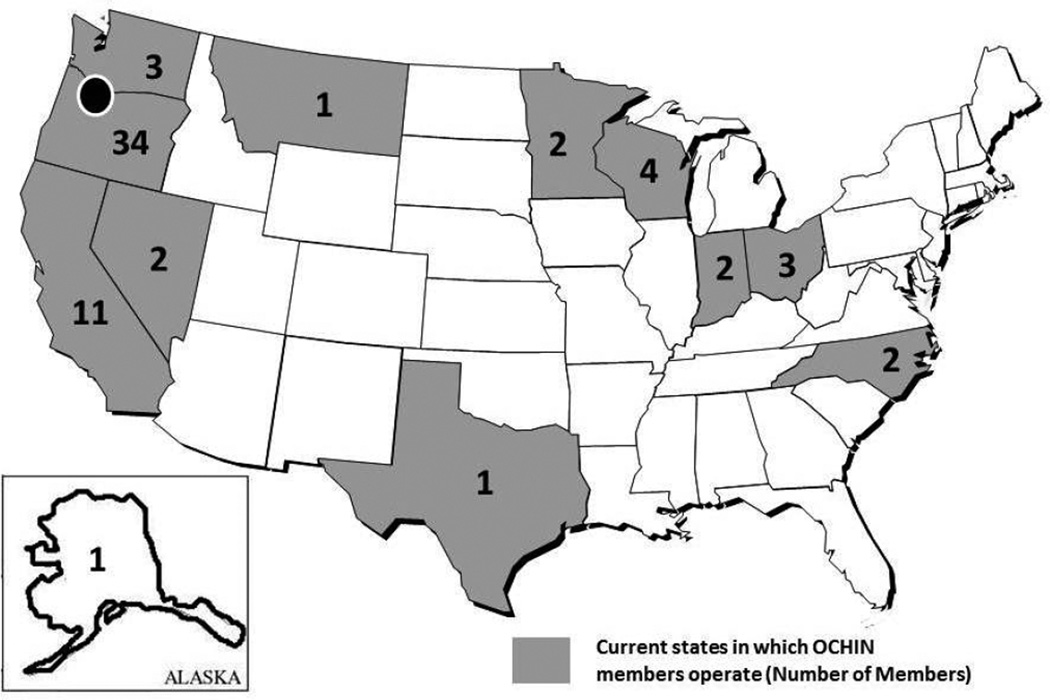

The OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN, founded in 2006 and registered with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2007, is unique in many ways. First, our network consists entirely of safety net clinics; members are federally qualified health centers and other similar entities providing primary care to vulnerable populations. Second, we are based in a nonprofit community organization rather than an academic health center: we were founded at the OCHIN community health information network, a coalition of community health centers that joined to support the adoption and sharing of emerging technologies. Originally called the Oregon Community Health Information Network (later shortened to “OCHIN, Inc” as members from other states joined), OCHIN is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) that provides health information technology, data aggregation and exchange, quality improvement, and reporting services to its members. OCHIN’s network now includes more than 1,200,000 patients at more than 200 primary care clinics across 12 states.14 Table 1 describes the mission and purpose of the OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN. Figure 1 shows the states in which current OCHIN members operate.

Table 1.

Mission and Purpose of OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN

| Mission |

|

| Purpose |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PBRN—practice-based research network

Figure 1.

Current States in Which OCHIN Members Operate

As with most PBRNs, participation in any of our research studies is optional for clinic and clinician members. We established processes to engage clinicians and staff in research, such as an early morning steering committee meeting, which is held monthly by conference call and open to clinicians and staff from all OCHIN member clinics. Prior to this meeting, our executive committee (which includes clinicians, researchers, and PBRN staff) meets to review and summarize proposals for our members and to oversee many of the administrative functions required to minimize the burden on community clinicians. We have also tested various models to determine how best to fairly compensate clinics and clinicians for their time.

Despite these measures, our long-term ability to achieve meaningful community-academic collaboration and publish research relevant to community primary care practices is still uncertain. To that end, we celebrated our fifth year by interviewing many of our PBRN’s founding members. These interviews were part of a reflective process that was intended to inform our PBRN’s future direction: to better understand original goals, identify gaps between the original vision and our current status, and solidify our research priorities and next steps. While also eliciting opinions about facilitators,15 we asked participants about perceived present and future barriers to conducting research relevant to primary care in the safety net. Here we present our thematic analyses of the most commonly reported barriers in hopes that these findings could distill information to (1) guide others who endeavor to build similar networks and (2) contribute to the national discourse regarding future challenges and next steps for improving PBRNs in research, so as to better serve poor and underserved patients.

Methods

Participants

Initially, we identified founding and current key members of the organization and other institutional leaders who were instrumental in developing the OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN. We then used snowball sampling techniques—soliciting recommendations from each interviewee about other people to contact—to identify additional key informants to participate in individual, semi-structured, in-depth interviews.16,17 Participants included physicians from network clinics, clinician-researchers and researchers at Oregon Health & Science University and the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Center for Health Research, and leaders from OCHIN and regional health care-related organizations. Table 2 describes the participants and their role in the PBRN. An introductory email was sent to 15 individuals suggested by the PBRN steering committee and OCHIN leadership; 14 responded and agreed to participate in the in-person interviews. Five additional potential participants were identified, contacted, and agreed to participate. Data collection stopped at 19 key informants, when interview data continued to confirm the existing framework without yielding additional concepts (saturation).18

Table 2.

Characteristics of OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN Study Sample*

| Position at Time of OCHIN Safety Net West’s Founding in 2006 |

Role in Relation to the OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN |

Years Actively Involved in OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN |

|---|---|---|

| Clinic leadership, medical director | Founder | 3 |

| Clinic leadership, medical director | Current SC member | 5 |

| Clinic leadership, medical director | Founder, current SC member | 6 |

| Clinic leadership | Founder, supporter | 2 |

| Institutional leadership | Founder, supporter | 2 |

| Institutional leadership | Early supporter | 1 |

| Institutional leadership | Founder | 2 |

| Institutional leadership | Founder | 3 |

| Institutional leadership | Founder, current SC member | 6 |

| Institutional leadership | Supporter | 3 |

| Institutional leadership | Early supporter | 2 |

| Physician | Current SC member | 5 |

| Physician | Current SC member | 3 |

| Physician | Current SC member | 1 |

| Physician, researcher | Current SC member | 3 |

| Physician, researcher | Early supporter | 1 |

| Researcher | Current SC member | 5 |

| Research staff | Founder, current SC member | 6 |

| Research staff | Supporter | 4 |

n=19

PBRN—practice-based research network

SC—Steering Committee

Founder: a person who was part of the initial organizing group. Not all founders were currently engaged with the network at the time of the interview.

Supporter: a person who provided funding, expertise, or other support for the nascent PBRN.

Interviews

Three team members with in-depth interviewing skills conducted interviews using a semi-structured guide (available from corresponding author upon request). All interviews were conducted in English. The interview guide was informed by a review of the literature about practice-based research and PBRNs and developed by members of the interview and analysis teams. It included a series of 12 open-ended questions designed to elicit perspectives about (1) the founding of the OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN and what factors initially brought people together, (2) facilitators and barriers to developing and sustaining the OCHIN Safety Net West PBRN, and (3) assessment of current progress and future goals.

Interviewers asked questions in the same sequence and used inductive probing on key responses. Interviews were conducted in or near Portland, OR, from August 2011 to November 2011, at participants’ offices or at OCHIN. One interview was conducted by telephone. Prior to each interview, consent documents were reviewed, and subjects were given the option to decline to have the interview recorded (none declined). Interviews lasted 35–60 minutes. Each interview was attended by two of the three team members, with one person primarily asking questions and the other taking detailed field notes. Interviews were recorded, and one of the interviewers listened to each of the recordings to supplement the field notes after the interviews took place, but they were not transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

Grounded hermeneutic editing methodology guided this qualitative data collection and analysis process.19–20 Our analysis team included a physician researcher with practice-based research expertise, a physician educator, a PhD nurse, and a PBRN community liaison, the latter two with qualitative research experience. The diversity of the analysis team allowed for multidisciplinary perspectives as well as the ability to detect assumptions or biases potentially affecting the analysis. After each team member independently read all field notes, we discussed emergent themes using a standard iterative process to create an initial thematic codebook.21 We repeated our individual reviews, then met again to refine the codebook. We also conducted a series of three in-person immersion/crystallization cycles to allow time for additional themes to surface.22 This process allowed us to assess agreement and variability in coding and work toward consensus until definitive patterns emerged22 and saturation of themes was assured.18 Key quotations are included in the results section below. (Supplemental quotations are available from the corresponding author on request). The study protocol was reviewed and deemed to be exempt by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (eIRB# 00007643).

Results

From our diverse group of interviewees, we heard several common challenges to the development of a robust PBRN in the safety net, which were grouped into four major themes. The four themes that emerged from participant narratives included: lack of research projects generated from clinician ideas, lack of appropriate funding, lack of clinician time, and lack of infrastructure.

Lack of Research Generated From Clinician Questions

Several interviewees commented on the paucity of clinician involvement in our current research activities. Most often, comments focused on how we have not been able to capitalize on clinician-generated ideas and move them forward into funded projects, as most of our current projects have been initiated by full-time researchers. The lack of meaningful clinician involvement in leading projects was noted to be a significant deficit: “There is not as much clinician-initiated research as I thought there would be, meaning research projects that come directly from OCHIN clinicians’ ideas.”

These types of comments were often followed by a call for higher levels of clinician involvement in the research activities of the PBRN. For example: “It would be a huge morale booster to actually figure out a way to conduct a study based on an idea from a Safety Net West clinician.”

Interviewees did not note specific resistance to clinician ideas; rather, they cited the need for “time for clinicians to really drive Safety Net West” and a general “need to facilitate clinicians to direct and suggest the research. If they did that, they would be more willing to devote time to it, and would get more buy-in at their clinics.” Our interviewees did not cite a lack of research training as a problem in our network. The other three themes—lack of appropriate funding, lack of clinician time, and lack of infrastructure support—provide plausible explanations for why clinicians have not achieved the high level of involvement that our PBRN’s founding stakeholders had originally envisioned.

Lack of Appropriate Funding

Respondents spoke about a lack of appropriate and adequate funding for the types of projects (including clinician-generated projects, as described above) that PBRN clinicians desired. This theme included general comments regarding insufficient financial resources such as “lack of funding,” “no funding, no dedicated staff,” “need more funding,” and the need for “increased [financial] support for clinicians to be involved with Safety Net West.” Participant comments focused on the pragmatic need for more funding as well as on the broader funding environment and its relevance to primary care research, especially in the safety net: “Traditional research models and funding sources don’t work well to do this kind of work,” and “Funders are looking for different outcomes than clinicians. NIH (the National Institutes of Health) doesn’t understand anything about primary care research.” Interviewees observed the “difficulty of getting grants to fit into a box at NIH. What is primary care research, after all? We’re not focused on a kidney, or a lung,” and cited the need to “work at the national policy level to create a funding environment that will support our research” and “advocate at a national level on why funding streams need to be different.” Concerns about adequate funding to do the work of the PBRN tied in closely with the next theme: lack of adequate time for clinicians to devote to research.

Lack of Clinician Time

Interviewees frequently identified lack of clinician time for engagement in the research process as a major challenge to achieving our intended vision. There were concerns about funding clinician efforts, illustrated by frequent comments such as, simply, “time and money” and “Clinician and staff time needs to be fundable.” There was also the recognition that safety net clinicians must juggle many competing demands for their time, and other priorities commonly rose above the PBRN. Interviewees remarked that it was “so hard to find the time” or “scheduling…you want to involve providers, but scheduling is very tough” or “Just remember that everyone had (and still has) a full-time job on top of their Safety Net West obligations!” Some participants did comment positively on clinicians’ ability to stay current with the PBRN’s projects through emails or attending occasional meetings by phone; however, a lack of time prohibited more in-depth involvement.

Lack of Infrastructure

Interviewees cited the lack of PBRN core infrastructure as a barrier to accomplishing and initiating early projects. Comments focused on two infrastructure-derived benefits. First, participants commented on the need for infrastructure to organize ideas and energy: (There were) “lots of ‘asks’ but no organized way to respond,” “There was a lot of excitement and will, but it was messy and undefined for awhile,” “no funding, no dedicated staff,” and “There was a lot of vision at Safety Net West but not the infrastructure needed to do research–we were over-balanced with ideas people.” These comments demonstrate the perceived need for a core infrastructure and at least a minimal level of organizational capacity. Second, participants remarked on the need for infrastructure and training to meet basic resource needs of PBRN members, particularly those without an extensive research background. They remarked that there was a “lack of know-how on IRB processes,” and that “administrative support at the PBRN was lacking.” Of note, some of the interviewees commented on how this area had improved the most significantly over the 5-year life of our network. Several interviewees believed that successful infrastructure development made possible through the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act had enhanced our capacity to do research, but the persistent lack of adequate and sustainable infrastructure support remained an oft-noted barrier to fully achieving our initial vision.

Discussion

Findings from this study, which aimed to describe our first 5 years of experience establishing a safety net-based PBRN, revealed four significant challenges to achieving our original goals, sustaining our network, and conducting robust and relevant research in the primary care safety net. These themes, described above, confirm previous reports from PBRNs housed in academic settings.23–25 By confirming these findings among various stakeholders in a community-based network serving underserved populations, our study is unique.

The themes shared a common thread: funding. According to our interviewees, primary care clinicians who serve marginalized populations have difficulty finding adequate time to work alongside researchers to develop in-depth, relevant, and fundable research ideas. Competing for this time is their significant clinical responsibility to serve patients on the “front lines” of the health care system. Traditional research funding streams often do not adequately compensate for this time (both the clinician salary and the potential lost revenue to the clinic). Traditional funding also does not fund the support staff needed by clinicians to conduct research or fund core PBRN infrastructure and activities that could foster stronger researcher-clinician relationships. Clinicians in community clinics, even in academic roles, may not have as much institutionally protected time for research activities as clinicians at academic centers. As observed in an assessment of infrastructure requirements of PBRNs, research funding typically acknowledges infrastructure needs by indirect funding rates; such funds can support equipment, space, and staff.26 Awards frequently support co-investigators who are often junior and developing research skills. Funding of this type rarely flows from funders or through university partners to practice-based research networks at a level that would be considered minimally necessary to conduct research in another setting. Finally, the long interval between grant submission and project initiation and the uncertainty regarding funding is perceived by our clinicians as unresponsive to their need for answers to real-time clinical questions. The motivations for increasing clinician involvement in a PBRN are well documented,27–31 but it is uncertain if these motivations can overcome some of the barriers identified among safety net clinicians.

Some possible solutions to these challenges have been demonstrated recently. Programs in Canada and the United Kingdom have provided funding to groups of primary care teams for development of research skills and infrastructure; such programs have resulted in research productivity.24,32–34 Direct and substantial infrastructure support from a parent university in The Netherlands has been a successful example of longstanding PBRN funding.24 In the United States, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed a PBRN Master Contract Program that funds focused research activities. While producing some projects, this program has been criticized for its low funding amounts, burdensome regulations, and inability to respond to PBRN member-led lines of inquiry.35 The NIH has invested in community engagement through Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA). CTSA awards are mostly directed to academic centers that can recruit primary care sites for research; however, some institutions have directly funded PBRNs. Even these funding mechanisms have increasingly directed funding toward academic rather than community centers of research.36

Despite these resources, networks in a variety of settings and nations still face the barrier of inadequate funding.24,31,35–38 An expansion of community funding mechanisms that provide the specific resources needed by clinicians caring for the underserved to partner with established researchers, clinic staff with research experience, unique administrative support, and faster grant cycles could greatly advance the health of the marginalized and underserved. As our interviewees point out, the long-term success of our PBRN may depend on new or different funding opportunities.

It has been more than 30 years since the “ecology” of medical care has been described, and more than 10 years since the same ecology was verified in the 21st century.8,9 These analyses illustrate that most health care services are still delivered and received in community settings, while most research is conducted in university-based, tertiary care settings. It has also been more than 20 years since the Institute of Medicine reported exceedingly long intervals between the issuance of research-based guidelines and the incorporation of these into community practice.39 Over the past several decades, these papers have implied that most research efforts focus on a small percentage of the population. Funders and large universities must direct increasing funds to practice-based partners; if we are to close the research-to-practice gap, it should not take another decade before our funding priorities adjust to our population realities.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we conducted interviews with key informants associated with a single PBRN with unique characteristics; thus, themes identified through these voices may not be generalizable to other settings. Rather, it was intended to provide a rich understanding of the vision, progress, and future direction of a unique, community-based PBRN of safety net clinics. A next step in this line of inquiry would be to develop a survey based on these findings that could be completed by PBRN members in other networks and settings. These themes could also be qualitatively evaluated further to elicit additional information and perspectives about these perceived problems and possible solutions. Second, there is the possibility that individual interviewers impacted the participant’s response based on their own inherent biases or because they were representatives of the PBRN or an academic health center. Third, while we used a snowball sampling technique to supplement our initial list of potential subjects, we may have missed some individuals who could have contributed additional information. Finally, while we used an iterative process to interpret the results, there was homogeneity in the perspectives of this highly educated group of clinicians and researchers, which may be an additional source of bias.

Conclusions

On the fifth anniversary of our PBRN, we interviewed founding stakeholders to elicit their perceptions of barriers between the PBRN’s founding goals and its achievements to date. The barriers our interviewees discussed—lack of clinician-generated and clinician-led research projects, lack of appropriate funding, lack of clinician time, and lack of infrastructure—share a common financial thread. For these barriers to be overcome our national health research priorities will need to be reorganized into funding mechanisms that recognize how care is delivered to its most needy citizens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the 19 PBRN members whose comments and ideas from recent interviews contributed to this commentary. We also thank Pam Rechel of Braveheart Consulting in Portland, OR, for providing facilitation at our strategic planning retreat. The authors are grateful for editing and publication assistance from Ms LeNeva Spires, Publications Manager, Department of Family Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University.

This study was supported by grant no. RC4LM010852 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Library of Medicine, grant no. UB2HA20235 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Center for Health Research, and the Oregon Health & Science University Department of Family Medicine.

References

- 1.Beasley JW, Hahn DL, Wiesen P, et al. The cost of primary care research. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(11):985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janosky JE, Laird SB, Sun Q. Content and context of a research registry for community-based research. J Community Health. 2008;33(4):270–278. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stange KC. Primary care research: barriers and opportunities. J Fam Pract. 1996;42(2):192–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aziz NM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivorship research among ethnic minority and medically underserved groups. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;29(5):789–801. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorsch JL. Information needs of rural health professionals: a review of the literature. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000;88(4):346–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sampselle CM. Nickel-and-dimed in America: underserved, understudied, and underestimated. Fam Community Health. 2007;30(1 Suppl):S4–S14. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinagawa SM. The excess burden of breast carcinoma in minority and medically underserved communities: application, research, and redressing institutional racism. Cancer. 2000;88(5 Suppl):1217–1223. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000301)88:5+<1217::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green LA, Fryer GE, Jr, Yawn BP, et al. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):2021–2025. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106283442611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White KL, Williams TF, Greenberg BG. The ecology of medical care. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1996;73(1):187–205. 1961. discussion 6–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green LA, Dovey SM. Practice-based primary care research networks. They work and are ready for full development and support. BMJ. 2001;322(7286):567–568. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7286.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green LA, Hickner J. A short history of primary care practice-based research networks: from concept to essential research laboratories. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindbloom EJ, Ewigman BG, Hickner JM. Practice-based research networks: the laboratories of primary care research. Med Care. 2004;42(4 Suppl):III45–III49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(Suppl 1):S12–S20. doi: 10.1370/afm.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devoe JE, Gold R, Spofford M, et al. Developing a network of community health centers with a common electronic health record: description of the Safety Net West Practice-based Research Network (SNW-PBRN) J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(5):597–604. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devoe JE, Likumahuwa S, Eiff MP, et al. Lessons learned and challenges ahead: report from the OCHIN Safety Net West Practice-based Research Network (PBRN) J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):560–564. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.120141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biernacki PWD. Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol Methods Res. 1981;10(2):141–163. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman L. Snowball sampling. Annals of Mathematics Statistics. 1961;32(1):148–170. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss A. Qualitative analysis for social scientist. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Addison R. A grounded hermeneutic editing approach. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research, second edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacQueen K. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1998;10(12):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research second edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tierney WM, Oppenheimer CC, Hudson BL, et al. A national survey of primary care practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(3):242–250. doi: 10.1370/afm.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Weel C, Smith H, Beasley JW. Family practice research networks. Experiences from three countries. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(10):938–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas P, While A West London Research Network. Increasing research capacity and changing the culture of primary care toward reflective inquiring practice: the experience of the West London Research Network (WeLReN) J Interprof Care. 2001;15(2):133–139. doi: 10.1080/13561820120039865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green LA, White LL, Barry HC, Nease DE, Hudson BL. Infrastructure requirements for Practice-based Research Networks. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(S1):s5–s10. doi: 10.1370/afm.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fagnan LJ, Handley MA, Rollins N, et al. Voices from left of the dial: reflections of practice-based researchers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(4):442–451. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.04.090189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green LA, Hames CG, Nutting PA. Potential of practice-based research networks: experiences from ASPN. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(4):400–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green LA, Niebauer LJ, Miller RS, et al. An analysis of reasons for discontinuing participation in a practice-based research network. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):447–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niebauer L, Nutting PA. Practice-based research networks: the view from the office. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(4):409–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roth LM, Neale AV, Kennedy K, et al. Insights from practice-based researchers to develop family medicine faculty as scholars. Fam Med. 2007;39(7):504–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carter YH, Shaw S, Macfarlane F. Primary Care Research Team Assessment (PCRTA): development and evaluation. Occas Pap R Coll Gen Pract. 2002;81:iii–vi. 1–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooke J, Nancarrow S, Dyas J, et al. An evaluation of the “Designated Research Team” approach to building research capacity in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glazier RH North American Primary Care Research Group. Modest but important progress in primary care research funding: the Canadian experience. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(3):272–273. doi: 10.1370/afm.1129. PubMed PMID: 20458115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pace WD, Fagnan LJ, West DR. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) relationship: delivering on an opportunity, challenges, and future directions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(5):489–492. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson KA. National Institutes of Health eliminates funding for national architecture linking primary care research. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(2):229–231. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.02.070012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soos M, Temple-Smith M, Gunn J, Johnston-Ata’Ata K, Pirotta M. Establishing the Victorian Primary Care Practice Based Research Network. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(11):857–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis MM, Keller S, DeVoe J, Cohen DJ. Characteristics and lessons learned from Practice- Based Research Networks (PBRN’s) in the United States. Journal of Health Care Leadership. 2012;4:107–116. doi: 10.2147/JHL.S16441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]